Prim Dent J. 2023;12(3):55-63

Learning Objectives

To highlight the use of the removable partial denture (RPD) in restoring anterior bounded saddles

To review the ‘rules’ related to the replacement of anterior teeth

To review the importance of avoiding visual components of the RPD in the aesthetic zone, concomitantly ensuring the required retention and support during function

Introduction

The Dental Impact on Daily Living (DIDL) is a socio-dental measure introduced in 1996 which included aesthetics. Using this standard, Al-Omri et al. investigated the impact of missing upper anterior teeth on daily living (Figure 1). They found that regardless of personal factors, anterior tooth loss had a definitive impact on patients’ satisfaction with their dentition.

Figure

No caption available.

Classification of the anterior bounded saddle

The anterior saddle that crosses the midline is classified according to Kennedy, as Class IV. If it does not cross the midline, it is classified as Class III. In this article, the anterior bounded saddle can be classified as either, depending on the crossing of the midline.

General problems associated with anterior bounded saddles

Because of its conspicuous location, aesthetics for the anterior bounded saddle restoration is of paramount importance, and therefore visible clasping of the abutment teeth and portions of the base are to be avoided where possible. However speech and function must be added to the most obvious reasons for a patient seeking treatment and hence the need to provide retention form that is positive and dependable.

Treatment options for anterior bounded saddles

1. Resin-retained fixed prostheses:

“Where a tooth-supported fixed prosthesis is indicated and the abutments are generally sound, resin-retained bridges are preferred, whilst recognizing that patient choice may be a factor limiting their use.”

2. Implant supported fixed restorations:

A systematic review found that implant-supported fixed restorations had an overall positive impact on Oral Health-related Quality of Life (OHRQoL), but patient satisfaction reduced as the number of replaced missing teeth increased.

3. Removable partial denture (RPD) treatment.

As an alternative form to fixed treatment, an RPD is seldom at the forefront of choice. Nonetheless, apart from financial considerations, there are important factors that may make the use of the RPD preferable, as discussed below.

Reasons for favouring RPD treatment include:

where there has been a considerable loss of alveolar bone, creating a large edentulous span

where there are clinical reservations regarding the longevity of fixed restoration abutment teeth

avoiding implant surgery, when the patient does not wish to have a surgical procedure

systemic factors that may contraindicate surgery

Ibbetson stated that “it remains appropriate that the simplest procedure that will satisfy the patient’s requirements, while providing a reasonable prognosis, should be the treatment that is advised.” Furthermore, it has been reported that it is the “duty of the provider of these services to utilise an evidence-based rationale when determining the best possible treatment for the partially dentate patient.”

In a literature review of the indications for removable partial dentures, Wöstmann et al. concluded that while there were no evidence-based indications and contraindications for prescribing RPDs, they noted that there were major underlying principles for clinical decision-making.

Davenport et al. selected “design statements” from the literature, which were subsequently modified considering comments received from experts, with further contributions by several prosthodontics specialists. The following are those design statements related to the replacement of anterior teeth.

Design statement 11.11: Anterior bounded saddles should be closely adapted to the guide surfaces of the abutment teeth to obtain good appearance and retention.

Design statement 11.12: Anterior bounded saddles should have backings if the opposing incisal edge is 2mm or less from the mucosa of the saddle area.

Design statement 11.13: Anterior bounded saddles should have a labial flange if significant labial resorption of the ridge is present.

Design statement 11.14: Anterior bounded saddles should have a partial labial flange extended to 1mm beyond the survey line on the ridge if there is minimal labial resorption and the smile line is low enough to conceal the junction between the flange and the mucosa.

Design statement 11.15: Anterior bounded saddles should have an open face, “gum-fitted” design, if there is no significant labial resorption of the ridge.

Drawbacks to the use of RPDs

The biological cost

Brill et al. noted the propensity for plaque to accumulate in the presence of an RPD and the subsequent effect on the teeth, particularly the abutments and the mucosa. Basic principles were arrived at by Owall et al. who found that, to prevent or at least minimise risks of oral tissue injury, there is a need to follow “open/hygienic design principles rather than biomechanical considerations”.

A systematic review on the impact of removable partial dentures on the health of oral tissues highlighted the importance of an integrated prosthodontics maintenance programme with regular recall visits. “Both oral and denture-hygiene care of an RPD patient cannot be underestimated and should be adopted as a gold standard in general dental practice.”

Patient concerns regarding the wearing of an RPD

When faced with the prospect of wearing a denture, the following factors can concern the patient:

1. The effect of the presence of a foreign body in the mouth

It has been reported that “Prosthodontists do not, as a rule, wear removable partial dentures and so have no feeling for the patient’s response to the addition of so much material in the mouth.” Thus, it is important that the dentist listens empathetically to the patient’s concerns and explains how it may be possible to allay their fears. It is crucial to ensure that the denture is “streamlined”, i.e. with the avoidance of food traps and making the framework as imperceptible as possible, particularly to the tongue to avoid lisping and other possible adverse effects to speech.

2. Aesthetics and retention

Due to the prominent position of the anterior saddle area, the patient is only too aware of the embarrassment that may occur if the denture moves or falls during speech/function. Thus, firm reliable retention is a major requisite. The choice and arrangement of the replacement teeth are essential as is the gingival architecture, however the natural effect can be destroyed by the visibility of the framework and its components, as can the patient’s confidence due to movement of the denture.

Overcoming problems with anterior bounded saddle treatment

Where anatomical and tooth positions are favourable, the following approaches can be considered as giving positive retention and avoiding direct visibility of denture components:

Designs that can enhance retention and reduce the visibility of denture components

Designs to overcome lack of intra-alveolar space

Designs to cope with extensive loss of alveolar bone and consequent large saddle areas

Designs to overcome conflicting undercut area

1. Designs that can enhance retention and reduce the visibility of denture components

The use of an oblique path of insertion

This makes use of the difference between an upward and backward path of insertion and the potential downward path of displacement, and resists downward displacement at right angles to the occlusal plane.

A rotational path of insertion

The denture base itself acts as retainer in the mesial undercut of the anterior abutments. Its use is limited by the need for good mesial undercuts and the absence of posterior spaces to be restored.,

The trip action effect

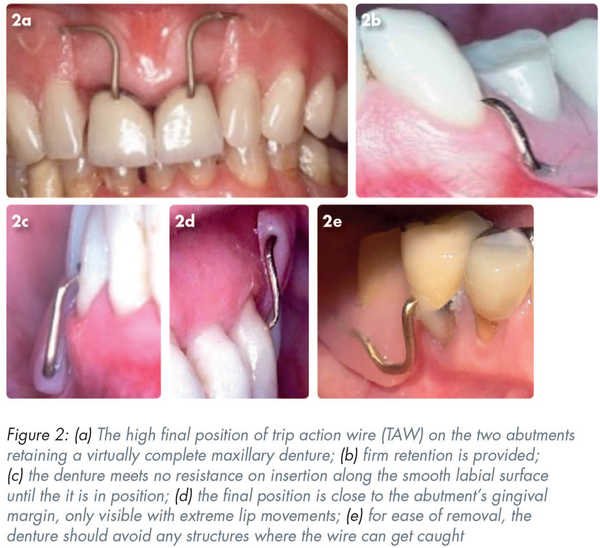

Introduced by Stone the theory was applied by Kabcenell. The reader can demonstrate the phenomenon by moistening the tip of the index finger and sliding it “downwards” along a smooth surface (e.g. a phone or table) and then pushing the finger “upwards”. As the angle of incidence increases, one should be aware of resistance, which increase to a maximum when the finger is at a right angle to the surface. This is the so-called “trip action”. Clinically, it results in the “clasp” on insertion sliding over the buccal/labial surface of the abutment. Removal of the denture is resisted by the “trip action effect”. Although it is inherent in all clasp actions, it is most usefully demonstrated with a 0.9mm round gold wire (trip action wire [TAW]). Figure 2a demonstrates the high final position of TAWs on the two abutments retaining a virtually complete maxillary denture.

Figure

No caption available.

The advantages of the TAW include the following:

it provides firm retention particularly in the absence of undercuts (Figure 2a-b)

as the denture is inserted it offers no resistance along the smooth labial surface until the denture is in position (Figure 2c)

once in place, it resists removal of denture along the line of insertion

its final position is close to the abutment’s gingival margin, only becoming visible with extreme movements of the lips and thus can be very effective on the labial surface of a canine abutment (Figure 2d)

any metallic glint can be overcome with gentle sandblasting

when the retention lessens, the wire can be gently bent tooth-wards until it is in firm contact. The patient can be shown how to do this with gentle pressure from the thumbnail

Disadvantages of the TAW include:

there is a need to avoid any structures in which wire can get caught as this will obstruct the removal of the denture (Figure 2e). Any irregularities on the facial surface should be polished or covered with a smoothed composite resin addition

as with all gingivally approaching clasps, it should not impinge on the sulcus during function

there is a need for a degree of digital dexterity from the patient

food may collect between the flange and mucosa

when used on anterior teeth, there is a risk that the clasp may be visible. However, an assessment of the lip length at rest and in function will provide the dental practitioner with a good appraisal of the effect of such a design. The risk/benefit can be discussed with the patient and those struggling with an issue with denture retention can have a great benefit

2. Designs to overcome lack of intra-alveolar space

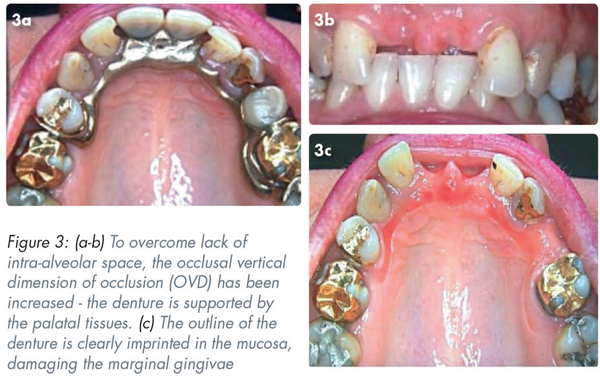

In Figure 3a-b the occlusal vertical dimension of occlusion (OVD) has been increased, and the denture is relying mainly on the support of the palatal tissues. Figure 3c shows the outline of the denture imprinted in the mucosa with the resulting damage to the marginal gingivae.

Figure

No caption available.

Generally, the lack of vertical space can be overcome with the application of the Dahl principle but not by making use of the alveolar mucosa alone as this will require tooth support from rests and even overlays. Nevertheless, it is important to exclude other causes of such an appearance, e.g. there may be an issue with cleaning of the prosthesis, including the patient wearing the denture at night, or in more rare circumstances a sensitivity to the metals of the framework – nickel and cobalt can cause a similar appearance.

The maxillary labial bar

This example of the use of a maxillary labial bar examines treatment where there is an extreme lack of interocclusal space.

When used as a major connector, a labial bar is usually confined to the mandible where lingually inclined teeth or exostoses make the use of a lingual connector impracticable. In the maxilla, the use of a labial bar may be indicated where there is a lack of intra-occlusal space to accommodate the denture’s components, as is seen in the following case.

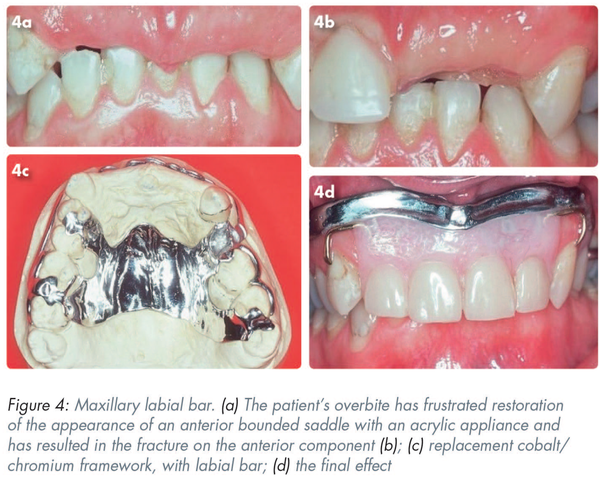

Figure 4 shows a labial bar being used in a situation where the patient’s complete overbite (Figure 4a) has frustrated the attempt to restore the appearance of an anterior bounded saddle with an acrylic appliance and has resulted in the fracture on the anterior component (Figure 4b). The replacement cobalt/chromium framework, with the labial bar, is shown in Figure 4c.

Figure

No caption available.

Figure 4d shows the final effect, where the denture teeth are “suspended” from the bar without interference with the occlusion. The teeth have been set closely to their original positions and are thus not interfering with the lip morphology or the function of the tongue. The labial bar is not visible nor are the gold TAWs giving retention on the canines.

3. Designs to cope with extensive loss of alveolar bone and consequent large saddle areas

Where there has been extensive destruction or resorption of the anterior alveolus with the saddle area extending posteriorly, the replacement RPD can become too unwieldy to be retained by routine retentive methods.

In this situation the retention of the extensive anterior bounded saddle is of major concern and thus there is a conflict between the use of retentive components and their visibility during function.

Treatment in the maxilla

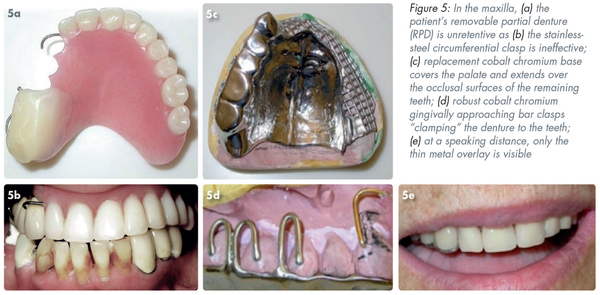

The acrylic RPD in Figure 5a is unretentive as the stainless-steel circumferential clasp on #13 is ineffective (Figure 5b) as is the use of a denture adhesive. The replacement cobalt chromium base (Figure 5c) has been designed to cover the palate and extended over the occlusal surfaces of the remaining teeth. Figure 5d shows robust cobalt chromium gingivally approaching bar clasps “clamping” the denture to the teeth #17, 16, and 15. Retention is further aided by the gold TWA on #13. In Figure 5e the only component that is visible at a speaking distance is the thin metal overlay on the canine, the reflective aspect of which has been dulled with sand blasting.

Figure

No caption available.

It should be noted that this problem can differ between the maxilla and mandible due to gravity. In the mandible the increased bulk can be of advantage to retention and stability.

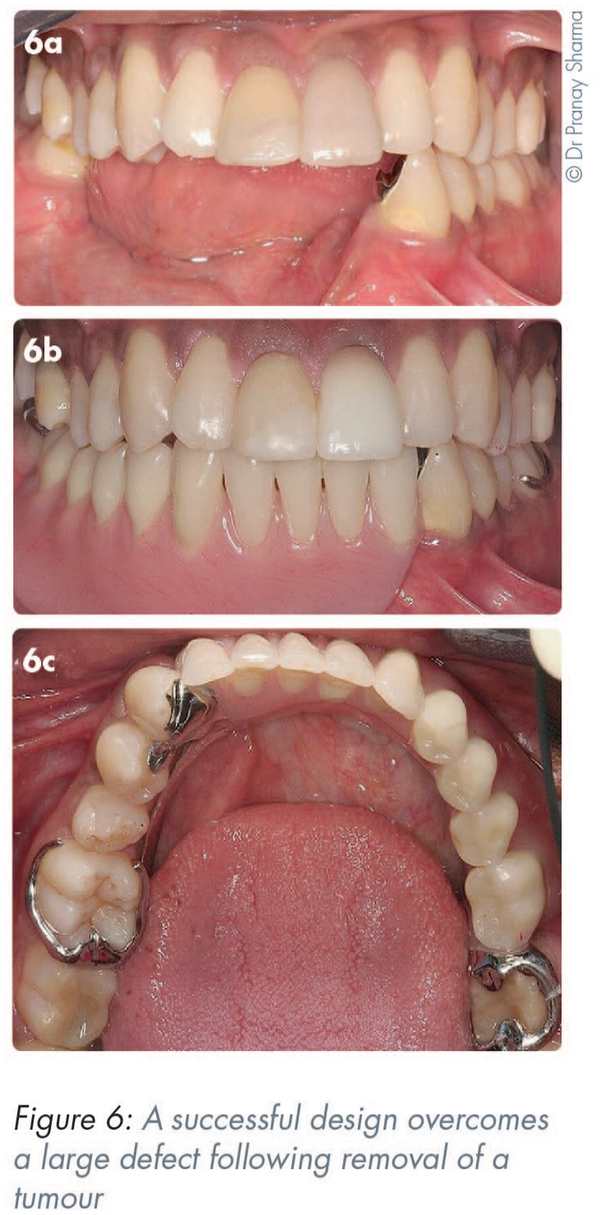

Treatment in the mandible

In Figure 6a, the removal of a tumour from the right-hand side has resulted in a large defect. An accurate impression of the teeth and soft tissues is essential. The absence of support for the long edentulous saddle is mitigated by the adhesively secured cast cingulum rest on #33. The shaping of the bulky acrylic base with respect to the tongue and cheek on the right-hand side has maximised retention (Figures 6b-c).

Figure

No caption available.

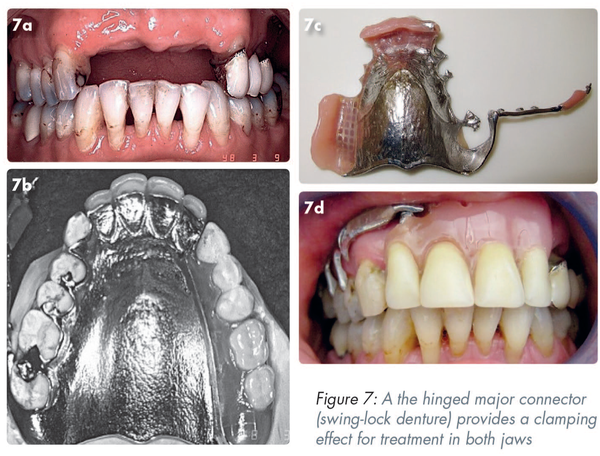

Treatment in both jaws

In essence, the hinged major connector (swing-lock denture), duplicates the clamping effect seen in Figures 5c and 5d. The teeth that complete the anterior bounded saddle (Figure 7a) are added to the full coverage chrome cobalt plate (Figure 7b). A mobile arm on the right-hand side attached to the framework (Figure 7c) clips into a lock and acts both as a splint and a retainer for the denture.,, (Figure 7d) As the framework covers a wide area of the gingival tissues it requires special attention for plaque control. Tooth support is essential to avoid damage to the supporting tissues. Patients will require some degree of manual dexterity to close/open the clasp.

Figure

No caption available.

4. Designs to overcome conflicting undercut area

The sectional (two-part) denture, comprises of at least two separate parts that engage the undercuts by different paths and are locked together in the mouth but can be separated to allow easy removal. While in situ, it:

eliminates the undercut spaces

provides very positive retention

can enhance aesthetics

The locking mechanism can be by means of:

split pins (see below)

locking bolts

tubes and clips

hinges

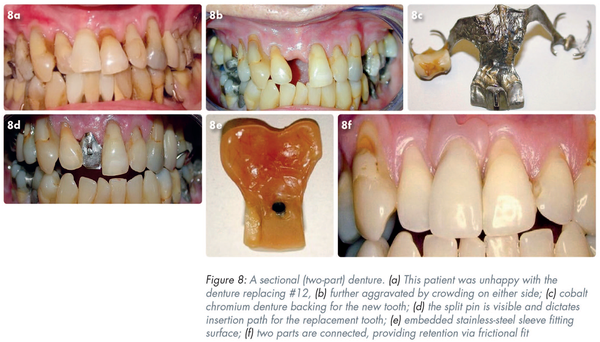

The patient in Figure 8a is dissatisfied with the appearance of her denture replacing #12. The space is constricted by the crowding caused by #13 and #11 (Figure 8b).

Figure

No caption available.

The cobalt chromium denture (Part 1) (Figure 8c) is the backing to the new tooth. In Figure 8d the split pin (two half-round sections of wiptam wire soldered to the framework) is visible.

This pin will dictate the path of insertion of the replacement tooth (Part 2). The fitting surface of Part 2 (Figure 8e) shows an embedded stainless-steel sleeve. In Figure 8f the two parts have been connected and are providing excellent retention by virtue of their frictional fit. The horizontal path of insertion of the tooth (Part 2) has eliminated the possibility of a “black triangle” and has allowed suitable gingival architecture.

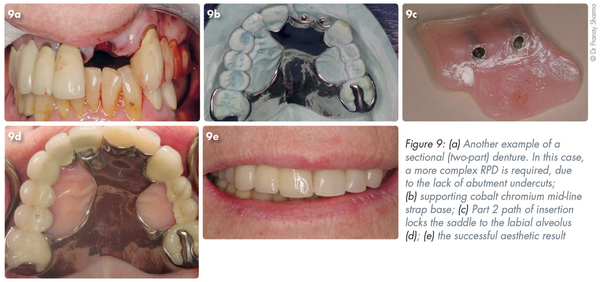

A further scenario is seen in Figure 9a. Trauma has resulted in an irregular alveolus in an otherwise complete dentition. The abutment teeth (#21, #33) are crowned and therefore the ideal fixed replacement (or implants) are unsuitable. Due to the lack of abutment undercuts a simple RPD will not provide effective retention. A cobalt chromium mid-line strap base (Part 1) provides support (Figure 9b). The path of insertion of Part 2 (Figure 9c) locks the saddle to the labial alveolus covering the defect aesthetically (Figure 9d-e).

Figure

No caption available.

Patients will require a degree of manual dexterity to remove and replace the Part 2. After time the frictional retention of the post will diminish but can be renewed by carefully inserting a scalpel blade between the split posts.

Support of the anterior saddle

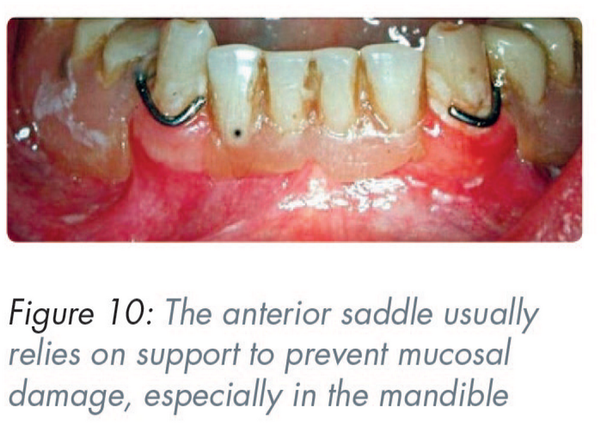

Due to its site, the anterior saddle, particularly in the mandible, often depends on support to prevent the underlying mucosa from damage (Figure 10). When planning a design, the following can be used as solutions:

overdenture abutments

cingulum rests

Figure

No caption available.

1. Overdenture abutments

The overdenture abutment can fulfil three functions:

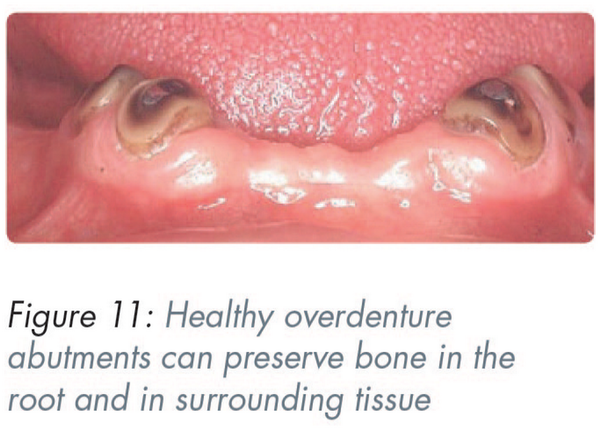

If kept healthy, it preserves the bone – not only that associated with the root but also of the surrounding tissues (Figure 11).

By supporting the saddle it prevents resorption due to occlusal forces. The lack of this support in the presence of plaque, often leads to so called “gum stripping” of the abutments.

The presence of the root surface positively identifies the position of the replacement denture tooth. This is extremely valuable where there is a doubt regarding the size/width of the replacement.

Figure

No caption available.

In this example, the patient was unhappy with the appearance of her front teeth which she considered too small, all the same size, and set in a uniform manner (Figure 12a). A faded photograph of her natural teeth indicated that they were set in a curve with prominent incisors (Figure 12b). Intraorally, the anterior bounded saddle extended from #12 to #23 and contained three overdenture abutments that once supported the crowns of #11, #21 and #22 (Figure 12c). The patient’s original denture contained four anterior teeth. Using the root surfaces as positive guides, three larger teeth were chosen to fill the space. They were more visible and gave lip support without the need of a flange and support for the saddle was maximised (Figure 12d).

Figure

No caption available.

2. Cingulum rests

The ideal support for a denture saddle comes from the abutment teeth. With the posterior teeth this is achieved by occlusal rests with or without prepared recesses for rest seats.

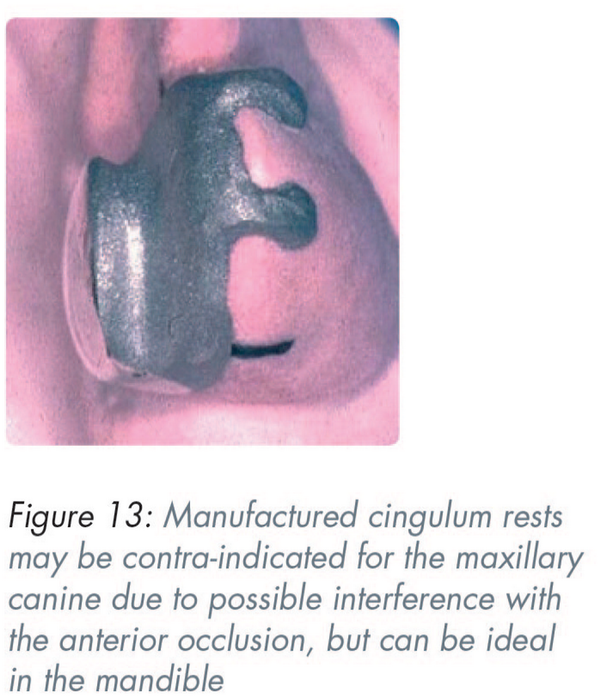

The inclined lingual surfaces of anterior teeth present problems with the provision of positive rest seats. The maxillary canine with a prominent cingulum may have an adequate thickness of enamel to allow the depth that a rest seat preparation requires. However similar preparations involving the mandibular canine are likely to cause dentine exposure. It is preferable to make rests with bonded etched metal, bonded composite resin or as part of a crown. Manufactured cingulum rests may be contra-indicated for the maxillary canine due to possible interference with the anterior occlusion but can be ideal in the mandible (Figure 13).

Figure

No caption available.

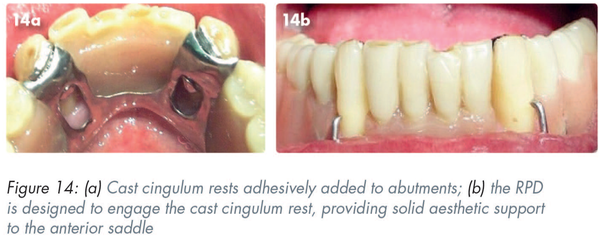

In this example, the cast cingulum rests have been added to abutments adhesively (Figures 14a and 6a). The RPD is designed to engage the cast cingulum rest and thus provide solid aesthetic support to the anterior saddle (Figure 14b).

Figure

No caption available.

Conclusions

Over recent years, the aesthetic and functional aspects of the anterior bounded space have been greatly enhanced with the advancement of adhesive dentistry and implant treatment. However, there are circumstances which make these options unsuitable and hence the need for an RPD.

According to Zarb and MacKay the successful Class IV RPD (anterior bounded saddle) must satisfy three basic criteria:

avoid harm to the periodontal tissues by adhering to open hygienic principles

have no conspicuous components

be retentive

The choice of an RPD requires considering a balance, i.e. matching the aesthetics of the fixed restorations, ensuring that the deleterious effects of wearing the denture are reduced to a minimum, but also maximising the sense of security.

The author would like to thank Dr Pranay Sharma for contributing the images used in Figures 6 and 9.

References

- 1. Leao A, Sheiham A. The development of a socio-dental measure of dental impacts on daily living. Community Dent Health. 1996;13(1):22–26.

- 2. Al-Omiri MK, Karasneh JA, Lynch E, et al. Impacts of missing upper anterior teeth on daily living. Int Dent J. 2009;59(3):127–132.

- 3. Kennedy E. Partial Denture Construction. New York: Dental Items of Interest Publishing Co., 1928.

- 4. Tyson K, Yemm R, Scott B. Understanding partial denture design. New York: Oxford University Press; 2007.

- 5. Davenport JC, Basker RM, Heath JR, et al. A clinical guide to removable partial dentures. Clinical guide series. 2nd ed. London: British Dental Journal Books; 2000.

- 6. Ibbetson RA. A contemporary approach to the provision of tooth-supported fixed prostheses part 2: fixed bridges where the abutment teeth require minimal or no preparation. Dent Update. 2018;45(2):90–100.

- 7. Ramani RS, Bennani V, Aarts JM, et al. Patient satisfaction with esthetics, phonetics, and function following implant-supported fixed restorative treatment in the esthetic zone: A systematic review. J Esthet Restor Dent. 2020;32(7):662–672.

- 8. Garcia LT, Cronin RJ Jr. The partially edentulous patient: fixed prosthodontics or implant treatment options. Tex Dent J. 2003;120(12):1148–1156.

- 9. Wöstmann B, Budtz-Jørgensen E, Jepson N, et al. Indications for removable partial dentures: a literature review. Int J Prosthodont. 2005;18(2):139–145.

- 10. Brill N, Gerd T, Stoltze K, et al. Ecologic changes in the oral cavity caused by removable partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1977;38(2):138–148.

- 11. Owall B, Budtz-Jörgensen E, Davenport J, et al. Removable partial denture design: a need to focus on hygienic principles? Int J Prosthodont. 2002;15(4):371–378.

- 12. Ezawi AAE, Gillam DG, Taylor PD. The impact of removable partial dentures on the health of oral tissues: A systematic review. Int J Dent Oral Health. 2017;3(2):1–8.

- 13. Brudvik JS. Advanced Removable Dentures. Batavia: Quintessence Publishing; 1999.

- 14. Watt D, MacGregor AR. Designing Partial Dentures. London: John Wright & Sons Ltd; 1984.

- 15. Lechner SK, MacGregor AR. Removable Partial Prosthodontics: a case-orientated manual of treatment planning. Prescott, AR: Wolfe Publishing; 1994.

- 16. Yip KHK, Fang DTS, Smales RJ, et al. Rotational path of insertion for removable partial dentures with an anterior saddle. Prim Dent Care. 2003;10(1):13–16.

- 17. Stone ER. Tripping Action of Bar Clasps. JADA. 1936;23(4):596–617.

- 18. Kabcenell JL. Effective clasping of removable partial dentures. J Prosthet Dent. 1962;12(1):104–110.

- 19. Dahl Bl, Krogstad O, Karlsen K. An alternative treatment in cases with advanced localized attrition. J Oral Rehabil. 1975;2(3):209–214.

- 20. Pullen-Warner E, L’Estrange PR. Sectional Dentures. A Clinical and Technical Manual. Bristol: John Wright & Sons Ltd.; 1978.

- 21. Karrir N, Hindocha V, Walmsley AD. Sectional dentures revisited. Dent Update. 2012;39(3):204–210.

- 22. Kratochvil FJ. Partial Removable Prosthodontics. Philadelphia: WB Saunders Company; 1978.

- 23. Zarb GA, MacKay HF. Cosmetics and removable partial dentures–the class IV partially edentulous patient. J Prosthet Dent. 1981;46(4):360–368.