Introduction

The single biological medical model has encountered great challenges in clinical practice. It is high time for gastroenterologists to recognize the inadequacy and limitation of the model in conventional gastroenterology (GE) practice, to take psychological and social variables into consideration together with developed and matured biological science and technology in the conventional model, and to apply the biopsychosocial model of medicine advocated by George Engel in the 1970s in clinical practice [-]. The holistic psychosomatic model of GE may help not only patients with “functional” GI symptoms but also patients with organic diseases such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), as well in terms of treatment and rehabilitation through psychosomatic assessment. A completely innovative system of mind-body GE, which may be termed psychosomatic gastroenterology (PSGE), could potentially be established.

A Brief Account of PSGE Practice in China

The general holistic model of medicine in China derives from traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). The holistic thoughts of integrating mind and body in TCM can be traced back to the Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor (Huang Di Nei Jing) over 2,500 years ago, which is an amazing classic text on not only medicine but also health-keeping in terms of global psychosomatic well-being. In this text and a few other ancient TCM texts, a pathogenic theory of emotional factors and pi zhu yun hua doctrine is recorded to guide physicians of TCM to understand and explain GI illnesses, and treat patients with such diseases.

Literally, the mechanism of pi zhu yun hua encompasses the concept of “the Spleen” (pi) – which is not the spleen as an organ in anatomy completely – “governing” (zhu) the “transportation” (yun) and “transformation” (hua) of food in the human gut [, ]. The treatment target for GI illnesses is pi, not the GI tract itself. However, the ancient holistic concept of medicine in TCM still remains at the level of medical philosophy and has not yet entailed any substantial clinical practice. On the one hand, practice models of GE in both TCM and Western hospitals are dominated by the biomedical model; on the other hand, some gastroenterologists in China have begun to treat functional GI symptoms with antidepressants and anxiolytics based on a psychiatric model. In recent years, a group of gastroenterologists have been making an effort to put the holistic concept of TCM into real GE practice by absorbing the operational research achievements from Western comprehensive psychosomatic medicine [].

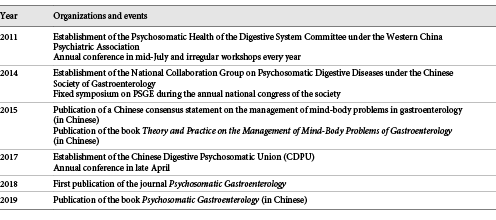

Related Organizations and Events

There has been no fixed unit or division yet within GE departments for psychosomatic practice in China’s hospitals so far. Psychosomatics is widely used in physicians’ personal practice, especially of those who work in units or divisions of functional GI disorders (FGIDs). Several PSGE-related organizations and events have been established in China in the past 10 years (Table 1).

Domains of PSGE Practice

Apart from the identification and management of psychosocial symptoms in FGIDs, a holistic psychosomatic model of GE should have a broader scope and set itself tougher tasks within the whole clinical process from first interview to rehabilitation: (1) assessment of primary functional GI symptoms; (2) evaluation of functional GI symptoms that occur in organic GI diseases, such as residual symptoms of IBD or IBD-irritable bowel syndrome (IBD-IBS) [-]; (3) examination of GI symptoms caused by obvious mental disorders and side effects of psychotropic drugs; (4) assessment of mental complications of organic digestive diseases such as hepatic encephalopathy and side effects of medications; (5) investigation of abnormal health-seeking behavior such as doctor shopping and cyberchondria of patients with severe GI disease phobia []; (6) assessment of iatrogenesis such as health anxiety or disease phobia induced or triggered by such medical terms or descriptions as Helicobacter pylori, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia of the gastric mucosal epithelium with negative implications regarding GI carcinoma; and (7) provision of psychosomatic rehabilitation [] for patients with both “functional” and “organic” GI diseases.

Currently, a small group of gastroenterologists in China are trying to construct a theoretical system and operational model of comprehensive psychosomatic medicine which covers the whole process of clinical care from psychosomatic interview [], assessment and diagnosis with tools such as the Diagnostic Criteria for Psychosomatic Research (DCPR) by Fava and Sonino [] and Fava et al. [], treatment [], and prevention of iatrogenesis to rehabilitation [].

Clarification of the Concept and Connotations of PSGE Practice

Diversity of Psychosomatic Models for GE

There are three main models of psychosomatic medicine [, , ]: (1) a branch or subspecialty of psychiatric medicine, nearly the same as consultation-liaison psychiatry (CLP); (2) a branch of medicine, a primary discipline independent of psychiatry, internal medicine, or surgery; and (3) a method or a practice model of holistic medicine to treat patients in various medical specialties including psychiatry. The respective models may be defined as a comprehensive, interdisciplinary framework for: (1) assessment of psychosocial factors affecting individual vulnerability to and the course and outcome of any type of disease; (2) holistic consideration of patient care in clinical practice; and (3) integration of psychological therapies in the prevention, treatment, and rehabilitation of medical disease [, ]. The models refer to taking biological, psychological, and social factors into consideration in a comprehensive and integrative way in the process of diagnosis and treatment of medical conditions [, ]. In China, psychosomatic medicine is still mainly used in CLP, even though recently it has become more and more popular in the medical setting [, ].

The psychosomatic practice model of GE has three main connotations or forms:

Biomedicine-oriented PSGE tends to explore the relationship between the brain and the GI tract by means of scientific technology such as neuro-GE; this form connotes “brain-body” medicine instead of “mind-body” medicine, since the brain itself is part of the body

Psychiatry-oriented PSGE, in the narrow sense, is essentially the same as CLP; in this model, functional GI symptoms are simply regarded as unrecognized or missed somatic symptoms of mental disorders

Holistic medicine-oriented PSGE; in this model, the synergistic effects of biological, social, and psychological factors are comprehensively considered in the process of interviewing, assessment, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation; it is strongly suggested that nonpsychiatric specialists such as gastroenterologists practice this model after short formal training in medical psychology, psychiatry, and psychosomatic assessment

Integration of Psychosomatic Assessment into GE

The GI symptoms of almost 60% of patients cannot be explained with the conventional disease-centered model of GE, which has not yet included unexplained symptoms of organic GI diseases such as the so-called residual symptoms of IBD [, ]. Biological assessment is inadequate to meet the needs of current clinical practice, and systematic psychosomatic assessment can provide a solution and will be a vital step in bringing about the transition of the biopsychosocial model from theory to operational clinical practice []. The two levels of functional analysis by Emmelkamp [], the DCPR by Fava and Sonino [] and Fava et al. [], and the clinimetric approach introduced by Feinstein [] may greatly improve the clinical process in shared decision-making and self-management, increasing the motivation for psychotherapy and psychoactive medication when really needed. These assessment tools related to nonbiological variables actually are the basis of the holistic psychosomatic model. There will be ample opportunity for its application in the medical setting [] including GE.

Psychosomatic Interventions for FGIDs

It is not easy for patients with FGIDs to accept psychological or even psychiatric attributions and related interventions for their symptoms. The key to solving this problem is to improve compliance with or the motivation for psychosomatic interventions []. It is not feasible – or is even wrong – for a clinician to attribute those unexplained GI symptoms to “no disease.” In the conventional model, typical conversations often occurring between physicians and patients could be along the lines of: “You can go back home now, since you have no disease!” from the physician’s side, and “Now what shall I do, doctor? I have a really uncomfortable feeling in my stomach!” from the patient’s side.

Understanding, explaining, and treating “functional symptoms” from the perspective of psychiatry undoubtedly is a move forward in GE practice. The Rome Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders put forward the basic framework and principles of psychological and psychoactive medicinal interventions for patients with FGIDs []. A meta-analysis by Ford et al. [] showed that psychotherapy and antidepressants were effective in improving the symptoms of IBS. However, if clinicians simply attribute “functional symptoms” to psychiatric disorders such as anxiety or depressive disorders, they go from one extreme of a “no-disease” attribution to another extreme which we call “jump reattribution” [].

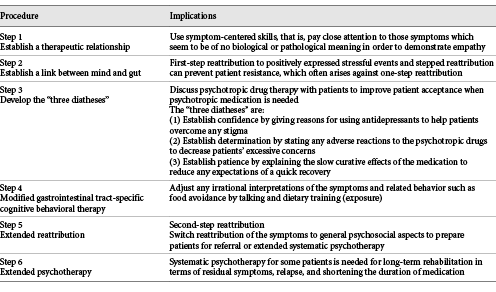

Psychiatry-oriented models for functional GI symptoms tend to make physicians pay more attention to antidepressants and less to psychological intervention. The psychosocial backgrounds of patients are complicated and various, but there is one thing they have in common, which is an irrational understanding or interpretation of the symptoms by themselves. It is unimaginable for a patient with GI symptoms to first see a psychologist or even a psychiatrist. Hence, in order to solve any psychological problems of patients with FGIDs, we should first of all solve the GI-related psychological problems, that is, specific recognition of a link between GI diseases and symptoms. After this, it will be possible to extend any psychological intervention to include more general aspects. Based on the above views, a symptom-centered, stepped reattribution model has gradually developed and achieved good clinical outcomes [, , ] with reference to classic cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and the core content of the reattribution model proposed by Fink et al. []. The specified steps and implications are presented in Table 2.

It is not so hard to see that the model is also suitable for the management of medically unexplained symptoms in other specialties apart from GE. Second-step reattribution seems to be very effective in that patients’ general well-being recovers further when it is combined with Buddhism or a more operational therapy implementing Buddhist thought, such as the well-being therapy (WBT) developed by Fava [], whose Chinese version (xin fu gan liao fa,) is available now []. CBT, WBT, and Buddhism basically share a common idea that is all about adjusting or changing people’s views or attitudes towards the world, life events, and health. CBT tends to help patients recognize and correct any negative aspects or perceptions of ill-being, while WBT and Buddhism tend to teach people to find out more about or experience the positive aspects of life or well-being perceptions. As a supplement to CBT or even independently, Buddhism and WBT are bound to find broad application in the management of FGIDs, especially in late stages of treatment; we had satisfying outcomes in several cases in our practice.

Case Report

Mr. Cai, a 35-year-old IT engineer, was a patient with complex FGIDs. In the course of seeking medical treatment, during 3 years he had visited gastroenterologists countless times and also cardiologists several times. He had been diagnosed with chronic superficial gastritis, inflammatory polyps in the gastric antrum by endoscopy with intestinal metaplasia, and mild atypical hyperplasia pathologically. Helicobacter pylori detection in his stomach had been positive one time. He had also visited various psychiatrists and had been diagnosed with anxiety disorder, depressive disorder, and somatoform disorder at different times. However, none of the treatments had worked well, and he had rejected psychotherapy and psychoactive medication from his psychiatrists.

He visited me 2 years ago. In the first interview, we discussed his various somatic symptoms without using any psychological terminology and assigned him the homework to describe his symptoms in detail and accurately with his own IT technique. He brought it back at his next visit. We discussed the homework and made a first-step symptom reattribution to disease phobia (gastric cancer and heart attack) according to the DCPR, as well as positively too his ambitious way of working. He agreed with the reattribution and accepted medical treatment with a proton pump inhibitor and a very low dose of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI). Three weeks later, his symptoms had relieved significantly. He continued low-dose SSRI treatment without the proton pump inhibitor till the end of 3 months. Then the dose of the SSRI was gradually decreased, and he accepted psychotherapy consisting of 4 sessions of CBT and 4 sessions mixed with Buddhism. He discontinued medication at the end of 6 months. He came again at the end of 11 months with a self-assigned homework report. Follow-up for another year showed that he was well and kept practicing Zen (sitting meditation) following my suggestion.

Psychosomatic Rehabilitation for “Organic” GI Diseases

The comprehensive psychosomatic model has great potential for application in the rehabilitation of patients with chronic “organic” diseases in many medical specialties such as cardiology [], pneumology, rheumatology, neurology, and endocrinology. Sonino and Fava [, ] defined rehabilitation as the sum of activities required to ensure that patients have the best physical, mental, and social conditions for progressing towards an optimal state of health.

Even though the results of their biomedical evaluation may show good recovery, the quality of life (e.g., lack of well-being, demoralization, and difficulties fulfilling personal and family responsibilities) of many patients may still by impaired for reasons that cannot be explained with the original internal disease [, ]. The same applies to GE. For example, some patients with IBD tend to have residual symptoms or “psychiatric morbidity” (particularly depression and anxiety) even when their organic lesions are reduced and the inflammation is inactive and under satisfying control with standard biological treatment []. There is a need for filling the gap between “hard” pathological data and “soft” psychosocial aspects []. Hence, it is necessary to introduce the concept of psychosomatic rehabilitation in GE.

In a preliminary clinical investigation conducted recently [], a psychosomatic practice model improved coexisting functional symptoms that could not be explained by ulcerative colitis itself. In that study, 60 patients with biologically qualified ulcerative colitis were randomly divided into a conventional intervention group and a comprehensive psychosomatic intervention group, with 30 patients in each group. Patients’ self-reported efficacy in terms of GI symptoms and global well-being, as well as results from the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS), were compared at the beginning and at the end 4 weeks after treatment to evaluate the outcome. The results showed that the residual symptoms had relieved, global well-being was improved, and the SAS and SDS scores were reduced in the comprehensive psychosomatic intervention group to a significant degree. Comprehensive psychosomatic care may potentially improve the rehabilitation of patients with IBD.

The scope of rehabilitation is very wide and heterogeneous. Generally, in practice, much more effort has been exerted on the “hard” data of pathology than on the “soft” psychosocial aspects. The soft part of rehabilitation should include patients’ disease-specific concerns and general psychological aspects. For any particular disease, psychosomatic intervention should focus on the particular psychological aspects first. For instance, in patients with IBD-IBS, specific psychological concerns include an irrational cognition of their gut, irrational food avoidance, recurrence and complications of IBD, and colon cancer phobia. Physicians should help patients to expose any irrational cognition of their gut and instruct them to do some cognition-related dietary training to overcome food avoidance and cultivate gut-specific perceptions of well-being. Then, the psychological intervention should be extended to general aspects of social functioning and daily life events. Thus, a comprehensive psychosomatic evaluation is needed for rehabilitation with particular diseases before any specified intervention. For IBD patients, for example, an evaluation should include at least four dimensions: (1) mucosal healing assessed by endoscopy; (2) the activity level of inflammation assessed with a scale such as the ulcerative colitis activity index []; (3) symptoms; and (4) psychological well-being assessed with the DCPR [].

Conclusions

A large number of clinical problems in GE involve not only biological variables but also psychosocial ones. Using a psychosomatic model of practice in GE does not mean that a gastroenterologist ought to switch over to psychological counseling, or even become a professional psychotherapist or psychiatrist. Rather, gastroenterologists are encouraged to transcend the limitations of the conventional model and to acquire some knowledge and skills from psychology, psychiatry, and psychosomatic assessment via brief special trainings and apply them in clinical practice of GE in a comprehensive psychosomatic way. There is an urgent need to establish a substantially new practice model that incorporates biological, social, and psychological factors in a unified way throughout the clinical course from interviewing, evaluation, treatment, and rehabilitation for GI illnesses with conventional functional GI symptoms and organic diseases []. PSGE, as an innovative concept and practice model, should be gradually developed.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Qiaoli Zhang for her efforts pertaining to this manuscript.

Statement of Ethics

The authors have no ethical conflicts to disclose.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare for this paper.

Funding Sources

J.C. has received financial support from the Changzhou municipal government talent program.

References

- 1. Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: a challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977;196(4286):129–36.

- 2. Engel GL. The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(5):535–44.

- 3. Engel GL. From biomedical to biopsychosocial. Being scientific in the human domain. Psychosomatics. 1997;38(6):521–8.

- 4. Cao J. Psychosomatic assessment to improve clinical practice with integral medical model[Electronic Edition]. Chin J Diagnostics. 2015;3(2):128–32.

- 5. Gastroenterology P. Integration of Western and Traditional Chinese Medicine. Beijing: People’s Medical Publishing House; 2019.

- 6. Cao J. Psychosomatic Medicine from philosophy to clinical practice[Electronic Edition]. Chin J Diagnostics. 2016;4(3):194–7.

- 7. Halpin SJ, Ford AC. Prevalence of symptoms meeting criteria for irritable bowel syndrome in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(10):1474–82.

- 8. Ren X, Zhang Q, Cao J. Clinical study on psychosomatic model in the treatment of ulcerative colitis complicated with functional symptoms. Chinese Journal of Digestion.2018;38(9):609–12.

- 9. Iskandar HN, Cassell B, Kanuri N, Gyawali CP, Gutierrez A, Dassopoulos T, et al Tricyclic antidepressants for management of residual symptoms in inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;48(5):423–9.

- 10. Long MD, Drossman DA. Inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome, or what?: A challenge to the functional-organic dichotomy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(8):1796–8.

- 11. Starcevic V. Cyberchondria: challenges of problematic online searches for health-related information. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86(3):129–33.

- 12. Porcelli P, Sonino N. Psychological Factors Affecting Medical Conditions. A New Classification for DSM-V. Adv Psychosom Med. Basel, Karger. 2007;28:174-181.

- 13. Fava GA, Sonino N. Psychosomatic assessment. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78(6):333–41.

- 14. Fava GA, Cosci F, Sonino N. Current psychosomatic practice. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86(1):13–30.

- 15. Cao J. Symptom-centered stepped reattribution model can improve the clinical management of functional gastrointestinal diseases. Chinese Journal of Digestion.2015;35(9):587–9.

- 16. Fava GA, Belaise C, Sonino N. Psychosomatic medicine is a comprehensive field, not a synonym for consultation liaison psychiatry. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12(3):215–21.

- 17. Zipfel S, Herzog W, Kruse J, Henningsen P. Psychosomatic Medicine in Germany: more timely than ever. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(5):262–9.

- 18. Fava GA, Sonino N, Wise TN. The Psychosomatic Assessment. Strategies to Improve Clinical Practice. Adv Psychosom Med. Basel, Karger. 2012;32:1–18.

- 19. Cao J. Challenge for conventional gastroenterology and discussion for psychosomatic model of gastroenterology. Chinese Journal of Digestion.2018;38(9):586–90.

- 20. Wei J, Zhang L, Zhao X, Fritzsche K. Current Trends of Psychosomatic Medicine in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2016;85(6):388–90.

- 21. Yuan Y, Wu A, Jiang W. Psychosomatic medicine in China. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(1):59–60.

- 22. Emmelkamp PM. The additional value of clinimetrics needs to be established rather than assumed. Psychother Psychosom. 2004;73(3):142–4.

- 23. Feinstein AR. Clinimetrics. New Haven: Yale University Press; 1987.

- 24. Porcelli P, Guidi J. The clinical utility of the diagnostic criteria for psychosomatic research: A review of studies. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(5):265–72.

- 25. Martens U, Enck P, Matheis A, Herzog W, Klosterhalfen S, Rühl A, et al Motivation for psychotherapy in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosomatics. 2010;51(3):225–9.

- 26. Drossman DA. The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(5):1377–90.

- 27. Ford AC, Quigley EM, Lacy BE, Lembo AJ, Saito YA, Schiller LR, et al Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies, including hypnotherapy, in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1350–65.

- 28. Cao J, Wang Y, Ren X, et al Clinical study of retribution-cognitive-pharmacy model in the treatment for irritable bowel syndrome. Chin J Behav Med & Brain Sci.2010;19(12):1069–70.

- 29. Ren X, Cao J, Zhu G, Wang Y. Clinical study of retribution-cognitive-pharmacy model in the treatment for functional dyspepsia[Medical Sciences]. Journal of Nantong University. 2014;34(2):132–4.

- 30. Fink P, Rosendal M, Toft T. Assessment and treatment of functional disorders in general practice: the extended reattribution and management model—an advanced educational program for nonpsychiatric doctors. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(2):93–131.

- 31. Fava GA. Well-being Therapy. Basel: Karger; 2016.

- 32. Cao J, Jiang R. (xin fu gan liao fa). Beijing: Chinese Medical Multimedia Press; 2017.

- 33. Rafanelli C, Roncuzzi R, Finos L, Tossani E, Tomba E, Mangelli L, et al Psychological assessment in cardiac rehabilitation. Psychother Psychosom. 2003;72(6):343–9.

- 34. Sonino N, Fava GA. Rehabilitation in endocrine patients: a novel psychosomatic approach. Psychother Psychosom. 2007;76(6):319–24.

- 35. Sonino N, Fava GA. Improving the concept of recovery in endocrine disease by consideration of psychosocial issues. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97(8):2614–6.

- 36. Seo M, Okada M, Yao T, Ueki M, Arima S, Okumura M. An index of disease activity in patients with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(8):971–6.