Introduction

Diagnostic systems provide a basis for choosing among treatments, designing studies of disease causation, and predicting the likely course and outcome of illness. It is understood that the modeling will be incomplete, i.e., that illnesses are more complex in structure than the diagnostic system []. The most frequently used diagnostic models assign patients to categories. But not all things fall naturally into categories. Some complex phenomena are better modeled as continuous features along a spectrum. Others are best modeled by combinations of key descriptive elements, or factors, with the elements often having degrees of severity.

In medicine, infections, such as diphtheria, or single gene disorders, such as sickle cell disease, fit well into categories, defined by their unique causes, even if presentations vary somewhat among patients within the category. Conditions with both multiple determinants and variable outcomes, such as type 2 diabetes and many cancers, fit less well into categories. Type 2 diabetes, with its interacting genetic and environmental risk factors, may be best described by individual features of clinical presentation. Moreover, while some cancers are largely determined by single gene variants, most appear associated with numerous variants, each contributing a portion of risk, and with many variants shared across different malignancies. Clinically, they are best described by combinations of factors, such as location, cell type, and degree of malignancy or tendency to metastasize.

Similarly, psychiatric disorders, including the psychoses, are complexly structured at multiple biological levels, from genetic and environmental determinants, through biochemical, physiological, and psychological processes, to clinical phenotypes [, ]. At every level, the elements associated with psychosis tend to vary among individuals with the same diagnosis and overlap the features of other disorders. As an example of causal complexity, thousands of loci contribute to the risk of psychosis, and 2 individuals with the same diagnosis may not have the same or highly similar risk-determining gene variants [, ]. Illustrating overlaps, psychotic disorders do not run true in families [-], and the genetic correlation of schizophrenias and bipolar disorders is high at rg = 0.70, reflecting the numerous gene variants shared between the 2 categories [, ]. The same findings apply for physiologic and brain imaging abnormalities and for signs and symptoms observed in these disorders []. They, too, are variable within a diagnostic category and often shared among diagnostic categories, including some neurological disorders. To a lesser degree, even healthy comparators may have the gene variants and imaging findings associated with psychoses [, -].

That 2 very different people with very different illnesses may get the same categorical diagnosis while 2 people sharing key underlying determinants and concomitants of illness may get different diagnoses is problematic []. Against that background, there has been a long-standing discussion of the validity and utility of alternatives to categorical diagnoses for modeling the psychoses []. Still, despite a century of attempts to modify categorical models to fit the clinical presentations of the psychotic disorders, and despite growing and compelling evidence that categorical models are not the best structural choice, they remain the basis of the standard US and international diagnostic systems. The DSM and ICD attempt to update their models regularly on the basis of new evidence. Such evidence has been slow in coming, but useful new results on the underlying structure of the psychoses have appeared. We explore the history and the evidence behind the categorical model and its alternatives and propose a different structural choice: a syndromic or factor-based model of the psychoses.

Methods

Many papers referenced in this narrative review were the products of previous searches in Medline on the nosology and structure of the psychotic disorders. In order to obtain more recent publications and any articles missed by past searches, we performed a new search of Medline using psychiatry as a major heading and with the following terms: schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, affective psychosis, bipolar disorder, psychosis, diagnosis, and nosology, alone and in combination. We also reviewed the reference sections and “cited by” lists of especially relevant papers to find other studies of interest. There are thousands of papers on these topics, so they cannot all be compiled, referenced, and compared in this review, the purpose of which is not to provide a meta-analysis of past results and reports but rather to summarize evidence on alternative diagnostic models and analyze the choices for describing the psychoses. Readers interested in more background details will find additional articles on the classification of psychoses referenced in the papers cited throughout the text.

Historical Background

Most ancient models of mental illness proposed diagnoses based on simple causes, including intoxications, demonic or divine possessions, and imbalances of humors. Some of these elements remain pertinent, including intoxications and biochemical abnormalities. Infectious agents that produce psychoses, such as the current COVID-19 [], might be seen as possessions. In addition, some ancient texts mention inherited factors underlying illnesses. In essence, historical diagnostic systems recognized a variety of relevant causes and proposed single-cause-per-case categorical models.

Modern diagnostic systems for psychoses, descended directly from the work of prominent clinicians, especially Emil Kraepelin, working a century ago, remain categorical []. His models, like the ancient ones, were largely based on conditions with single determinants, such as the recently discovered infectious diseases (specifically, syphilis) []. It is true that single causes, including drug use, metabolic abnormalities, nutritional deficits, and autoimmune disorders, may lead to psychosis []. Similarly, rare genetic variants, usually either de novo copy number variants or loss-of-function point mutations, may explain a substantial portion of the risk for uncommon cases of psychosis [, ]. However, for most cases, contrary to the single-cause model, numerous interacting factors each contribute a modest proportion of risk [].

Regarding the types and number of psychotic disorders, both unitary models and multiple disease models have been considered. Unitary models propose a single disease, a primary psychosis with multiple presentations []. More often, disease models with multiple categories are favored, as in the DSM-5 and ICD-11. Kraepelin proposed 2 categories for the most common psychoses not due to organic causes known at the time, i.e., a category of early onset and usually chronic psychosis, initially designated Dementia Praecox but later called schizophrenia, versus typically recurrent psychosis with prominent affective features, initially called manic-depressive insanity and later divided into what became bipolar disorders where manias were observed and unipolar or major depressions where manias were not observed. He hoped each would have a unique and specific cause.

Notably, the term “schizophrenia,” from Eugen Bleuler, originally referred to a variety of conditions in which aspects of cognition were poorly coordinated []. Bleuler was not describing a single condition with a primary single cause and specifically referred to the “group” of schizophrenias. Kraepelin was not rigid in his own conceptions and, particularly in his later writings, he questioned the division of psychoses into 2 separate categories. Many others have critiqued models with only 2 or just a few categories [-].

In fact, both schizophrenic and affective psychoses have usually been understood as plurals, i.e., disorders that are heterogeneous in underlying mechanisms and clinical presentation. In addition, recognizing an irreducible overlap in symptoms shared among schizophrenic and affective presentations, another major category, with mixed symptoms, was added, i.e., acute schizoaffective psychoses. It was first suggested by Kasanin [] in 1933 and is now incorporated in schizoaffective disorders. Other systems or criteria have been proposed, including those of Kurt Schneider [], especially his first-rank symptoms to define the category of schizophrenia, and Karl Leonhard [], especially his suggestion of the category of cycloid psychoses; see Peralta et al. [] for an excellent summary of the nosologic system of Leonhard []. Neither the key concepts of Schneider [] nor those of Leonhard [] were confirmed by subsequent study or remain in the current standard psychiatric models, so they are not further discussed below. Rather, the most common idiopathic psychoses are still primarily divided into schizophrenic and affective types. Schizoaffective disorder remains as a major diagnostic category or subcategory of psychosis. To these, standard models add a few less commonly observed categories, as noted below.

Current Diagnostic Systems

The most frequently used diagnostic systems are the DSM, produced by the American Psychiatric Association, and the ICD, produced by the World Health Organization. Both the DSM and the ICD are periodically updated. In that process, expert consensus is sought, but changes are not expected to be based purely on consensus; they are to be evidence based. In all recent versions of the DSM and ICD, the primary structure has been the specification of categorical diagnoses.

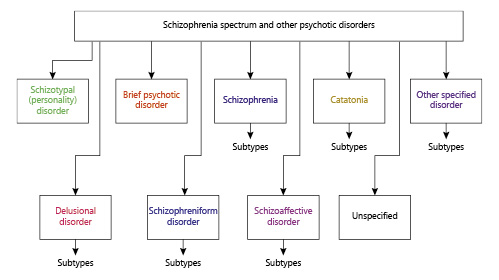

The DSM and ICD share many features in their classifications of the psychotic disorders []. The current DSM, i.e., DSM-5, and the proposed ICD-11 each have a major category of schizophrenia-related disorders. In the DSM-5, that group is called “schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorders” and it includes schizophrenia itself, along with schizotypal personality disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder, brief psychotic disorder, schizophreniform disorder, and catatonia, as well as various other specified and unspecified psychotic disorders. Many of these high-level categories have subtypes. A graphic of the DSM-5 schizophrenia spectrum is shown in Figure 1. Although a “spectrum” classifies items along a one-dimensional scale, it is not stated in the DSM-5, or clear by inference, what defines that dimension, especially as the categories and subcategories do not obviously differ along any scale of severity, type, or number of key symptoms. DSM-5 schizophrenia, itself, is characterized by delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, grossly disorganized or catatonic behavior, and/or negative symptoms. Only 2 items from that list are needed for a diagnosis, so different patients may have nonoverlapping presentations. Signs and symptoms must be present for a continuous period of at least 6 months and they must be more prominent than affective symptoms. The number of episodes and whether the patient is currently in an episode can be specified.

Fig. 1

DSM-5 model of the schizophrenia-related psychoses. Only the psychoses not associated with drug use or other medical conditions are shown. Each category specifies the criteria and the number of these that needs to be met in order for a diagnosis to be made. Other specified disorder in full is: other specified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder. Unspecified in full is: unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder.

In the ICD-11, the similar category is “schizophrenia or other primary psychotic disorders,” under which there is a listing for schizophrenia, itself, as well as schizoaffective disorder, schizotypal disorder, acute and transient psychotic disorder, delusional disorder, and 3 categories of other presentations of psychosis that do not fit the major categories. Each parent category is referred to in the singular. However, individual aspects of presentation that differ between patients can be noted. Schizophrenia, itself, is characterized by distortions of thinking and perception, with a course that can be continuous or episodic, with incomplete or complete remissions. The clinical presentation can include affective symptoms or psychomotor disturbances, though catatonia, per se, is in its own separate category. As in the DSM-5, two patients within the same diagnostic category can have very different presentations and courses.

For affective disorders, the DSM-5 makes a division between “bipolar and related disorders” and “depressive disorders,” though it is acknowledged they are not always easy to distinguish. Bipolar disorders include bipolar I and bipolar II disorders, along with cyclothymia disorder and other specified, as well as unspecified, bipolar and related disorders. Bipolar I disorder may have psychotic features. Both mood congruent and incongruent (schizophrenia-like) psychotic signs and symptoms can be seen, including hallucinations, delusions, and catatonia, along with grossly altered speech and behavior. Course is a subspecifier and can be single, episodic, or chronic. Similarly, along with mood symptoms, psychotic symptoms may be seen in depressive disorders and some subtypes.

As in the DSM-5, the presentations of affective disorders in ICD-11 are many and diverse. ICD-11 has a major category of “mood disorders.” Under that parent category is a subcategory of “depressive disorders,” which can have psychotic symptoms specified, and “bipolar or related disorders,” with further subcategorization into bipolar type I and type II disorders, each singular, cyclothymic disorder, and some residual disorders. Both bipolar types I and II can have psychotic presentations.

Background on Alternative Models

Primarily categorical systems, usually with additional subtyping, as in the DSM and ICD, have remained the chief models ever since Kraepelin. They have been modified over time, on the basis of changing opinion and evidence, but the changes have usually been modest []. Epidemiologic studies have suggested dimensional features be added to categorical diagnoses []. The DSM-5 includes the potential use of dimensional features of presentation, but they are not in the main text delineating the diagnostic categories. Dimensional elements are included in the ICD-11 as well, but as optional specifiers within the psychosis categories []. Thus, both the DSM-5 and the ICD-11 are categorical models with some modifiers, but these modifiers have not been widely adopted in current practice [].

The relationship among the many categories of psychosis has been discussed widely. Much discussion has focused on schizoaffective presentations, since they overlap other diagnostic entities so extensively in signs, symptoms, and course and because they are not reliably distinguishable from either schizophrenia or affective psychosis [, , ]. Some have suggested that schizoaffective disorders are more like schizophrenias, some have suggested that they are more like affective disorders, and some believe that they are best considered a separate entity, at least until more is known.

Separately, recognizing the lack of separation among or boundaries between the psychotic disorders, models based on continua of symptomatology, instead of categories, have been proposed []. In addition, rather than adding dimensional features to a diagnostic structure primarily based on categories, some have suggested employing a multidimensional approach, with classification of psychoses by key factors or dimensions of illness, not categories, as the primary diagnostic framework [].

Assessing Categorical Models of the Psychoses

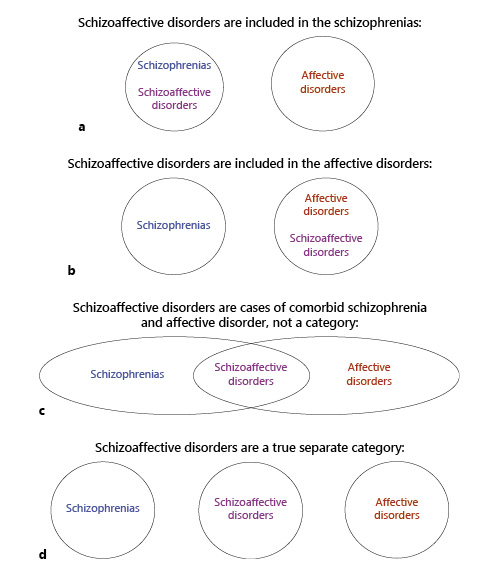

True categories are separate entities with characteristic features that define them. Several models attempt to fit the psychoses into true categories. Graphic representations of categorical alternatives for common presentations of major psychoses (schizophrenias, schizoaffective disorders, and affective psychoses) are shown in Figures 2 and 3. Retaining a kraepelinian dichotomy (Fig. 2), the psychoses can be modeled as divided into schizophrenic and affective types, with all presentations included in one or the other category. Thus, schizoaffective psychosis, along with a variety of other psychoses, can be a subtype of schizophrenia, as suggested in the DSM-5. In this model, all psychoses, except those in which affective symptoms are predominant, are schizophrenias (Fig. 2a). Alternatively, schizoaffective disorder may be seen as a part of the affective psychoses (Fig. 2b []. This configuration has often been suggested because psychotic symptoms can be as great or greater in bipolar disorders, especially untreated bipolar disorders, as in schizophrenias []. Other psychoses, without prominent affective symptoms, could remain in the category of schizophrenias.

Fig. 2

True categorical models of the major psychoses: less common psychoses are not shown but, if added, they would be separate categories. a Schizoaffective disorders are included in the schizophrenias. b Schizoaffective disorders are included in the affective disorders. c Schizoaffective disorders are cases of comorbid schizophrenia and affective disorder, not a category. d Schizoaffective disorders are a true separate category.

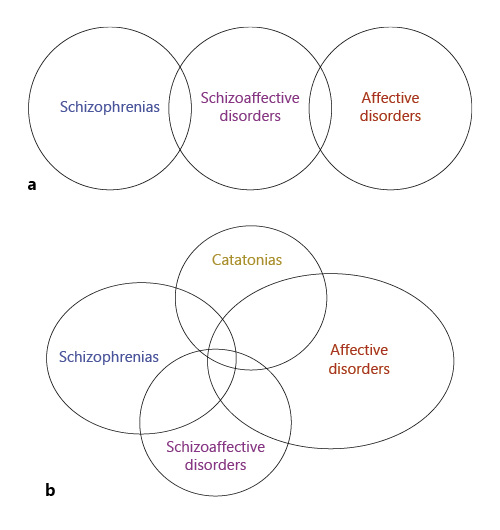

Fig. 3

Overlapping categories model of the psychoses. Schizoaffective disorder includes elements of schizophrenia and affective disorders. It may be partly overlapping and partly separate from other major psychoses (a). Other psychoses may also overlap the major psychoses; catatonias are shown as an example (b).

Also retaining 2 main categories, some have suggested that cases of schizoaffective disorder are simply instances of comorbid schizophrenia and affective disorder (Fig. 2c) []. However, if that were true, then the prevalence of schizoaffective disorders would equal the prevalence of schizophrenias multiplied by the prevalence of affective disorders. Using survey estimates for the prevalence of schizophrenias (1.2%) and any mood disorder (7.1%), schizoaffective disorders would have a population prevalence of about 0.08% []. However, the prevalence of schizoaffective disorders appears to be at least an order of magnitude higher [, , ], which is inconsistent with a simple dichotomous categorical model of schizophrenic and affective disorders, with schizoaffective presentations being comorbid cases.

Of course, it is not necessary to restrain the model to 2 categories, and schizoaffective disorders may be seen as separate from either schizophrenias or affective disorders (Fig. 2d). That is, it may be its own category. The same may be true of all or some of the other less common psychoses listed with schizophrenias in the DSM and ICD systems. (That model is not shown in the Fig. 2.) Such strict categorical separations of all of these disorders are not used in any current model and, like the 2 or 3 category model, they do not fit the presentations or biology, including the genomics, of the psychoses [-]. Rather, all of the psychoses seem to be related and overlapping in determinants and presentation.

Thus, as appealing as pure categorical systems may be, none of them fit the biological and clinical evidence []. Schizophrenias, schizoaffective disorders, and affective psychoses share causes, underlying processes, and clinical features. Moreover, their courses or responses to treatments are not unique []. Rather, cases of transient nonaffective psychosis and cases of chronic affective psychosis are not infrequently observed, and various medication and psychosocial interventions are helpful in patients with different diagnoses and not just one or another diagnosis.

For this reason, modified categorical systems with partial overlaps have been proposed. A diagram of this model for the schizophrenias, schizoaffective disorders, and affective psychoses is shown in Figure 3a. Overlaps include the features schizoaffective disorders share separately with schizophrenias and affective psychoses [] but should also reflect overlaps in genetic and clinical features between schizophrenias and affective psychoses, themselves []. Moreover, other psychoses (e.g., catatonic or single delusional disorders) could be added, with each overlapping one or more of the other presentations [e.g., ]. Adding catatonias is shown in Figure 3b, with each disorder overlapping all of the others, while noting that catatonias appear more commonly in affective than schizophrenic psychoses []. The overlaps accommodate the absence of causal or symptomatic boundaries between the diagnostic groups and acknowledge that the diagnoses are not true and separate categories. Taking these features one step further, it has been suggested that the major psychotic disorders do not just overlap but may be on a continuum of presentations [].

Continuum Models of the Psychoses

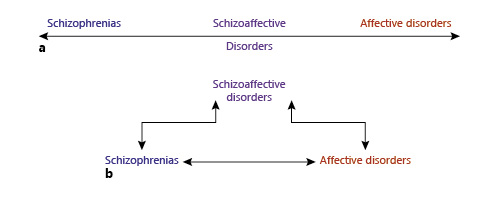

If the relative prominence of key cognitive and affective symptoms is key, perhaps schizophrenic-like and affective-like presentations are along a continuum of thought and mood disturbance. Such proposals often align diagnostic categories in one dimension, with schizophrenias at one extreme, affective psychoses at the other, and cases of schizoaffective disorders in the middle, as in Figure 4a. However, there is no clear evidence from genetic or biomarker studies for such a line. Instead, given the overlaps between schizophrenic and affective psychoses, per se, as well as their overlaps with schizoaffective disorders, perhaps it would be more accurate to show the relationship among psychoses as being the closed circuit in Figure 4b. However, as with the DSM-5 schizophrenia spectrum concept, it is unclear what the lines connecting the entities in Figure 4a or b would mean, and neither continuum model comfortably fits the other psychoses listed in the DSM-5 and ICD-11.

Fig. 4

Continuum models of the major psychoses. Schizoaffective disorder is related to both schizophrenia and affective disorders without any separation along a spectrum without boundaries. That may be a line in which there is no direct connection between schizophrenia and affective disorders, except through schizoaffective disorders (a), or all 3 presentations may be directly related in some way (b).

Continuum models have the useful feature of employing degrees of severity of schizophrenic-like or affective-like symptoms to characterize psychoses. However, whether along a line or around a circle, the major disorders are arrayed in one dimension. Like the use of “spectrum” for the schizophrenias, one dimension does not capture the broad range and complex presentations of cases seen in practice. Following that observation, it has been suggested that, instead of individual cases being presentations varying along a spectrum or grouped by a few key shared or similar features, perhaps the disorders vary along multiple dimensions of illness and should be classified that way.

Multidimensional Factor-Based Models of the Psychoses

Numerous independent groups have analyzed the clinical presentation of the psychoses and observed an underlying factor-based or dimensional structure []. Specifically, agnostic modeling by a variety of statistical methods finds that psychoses can be described by a combination of these major factors: positive symptoms of psychosis, negative symptoms of psychosis, manias, and depressions. Some studies suggest utilizing additional descriptive factors [], including disorganization, specific cognitive dysfunctions, and behavioral disturbances [, ]. To these can be added other important factors that are less specifically related to the psychoses, such as anxiety, substance use, suicidality, hostility, a lack of insight, and motor abnormalities, including catatonia. Using just 4 major factors produces a better fit to clinical presentations than standard categorical diagnoses []. Employing more factors, such as disorganization, can produce an even better description of cases [].

These syndromic factors are not categories. They can be single prominent features of illness, such as hostility, but more commonly they are clusters of related signs and symptoms generally seen together, so-called syndromes, such as negative symptoms or mania. These key factors arise from observations of numerous cases, as did the models of Kraepelin and others a century ago. Each individual case is described by a combination of factors, as illustrated for a few syndromic factors in Figure 5. Each patient seeking treatment or enrolled into a study can be characterized in a multidimensional space according to the presence and severity of the symptomatology on each chosen factor.

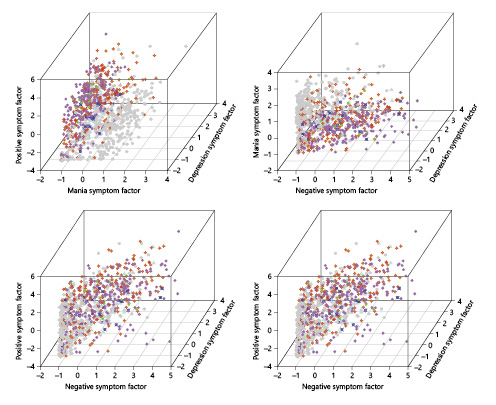

Fig. 5

Factor-based dimensional models of the psychotic disorders. Individual patients can be described by any number of assessed factors, but graphic representations are limited to 3-D on paper. The examples shown are for 934 hospitalized patients with psychotic disorders []. Factors ratings, representing the degree of symptoms, are on the axes. For reference, diagnoses (DSM-IV) are in colors: gray, bipolar disorder; magenta, schizophrenia; red, schizoaffective disorder; green, schizophreniform; aqua, major depressive disorder; blue, psychosis not otherwise specified. Categorical diagnostic groups show their known characteristics of some degree of separation along with substantial overlap in symptoms. There are no true categories evident.

Notably, patients with different diagnoses will be at different densities at different places in a multidimensional factor space, but they do not fall into clearly separate clusters in that space. Rather, those with what are currently called schizophrenias will be more densely observed in some parts of the space, such as the area of high negative and low manic symptoms, but their distribution will overlap substantially with patients given other diagnoses, consistent with the lack of boundaries observed in studies of categorical diagnostic systems. Examples of such overlaps, confirmed by the mathematical analysis, can be seen by looking at the factor space distributions shown in Figure 5. In essence, Figure 5 is a visual representation showing that factors are a more complete representation of cases than categorical diagnoses. Categorical diagnoses group individuals with quite different presentations together. Factor-based models do not; they accommodate both the shared and different aspects of each case. Factors can flexibly incorporate some or all of the known or observed features of the psychoses. Any combination and degree of factors can be specified, to any degree of detail desired for various clinical or research purposes.

In a factor-based model, the use of categories need not be abandoned. However, categories become secondary rather than primary classifications. That is, useful categories can be created by grouping patients with similar factor-based presentations together. For example, most patients with mania may respond to similar treatments, but no case with mania need be forced into a category such as bipolar disorder versus schizoaffective disorder. In clinical settings, categorical designations are often accompanied by the use of “other” or “not otherwise specified” diagnoses, meaning the case does not fit a major category, or “rule-out” diagnoses, specifying more than one category to describe a patient [, ]. Patients may receive discharge diagnoses such as: “schizophrenia, R/O schizoaffective disorder, R/O bipolar disorder type I with psychotic symptoms,” and these rule-outs may persist in the record over numerous hospitalizations. Rather than reflecting poor diagnostic competence, those unresolved alternatives may reflect the well-documented limitations of categorical diagnoses in characterizing patients as they actually present for assistance. Using a factor-based model, many now diagnosed with schizophrenia might fit better being described as having a chronic course of psychosis with positive and negative symptoms but without manias or depressions. If there are manias or depressions, that can be explicitly stated, instead of diagnosing schizoaffective disorder. The characterization of each patient can evolve with further observation but would need no rule-outs.

The findings and discussion above emphasize symptomatology, but not all factors need to represent presenting features of illness. Course is an essential factor to specify for all cases in any model. Moreover, determinants of risk, such as social circumstances, can be included. (The ICD-11 has a category for disorders specifically related to stress, though it is separate from the psychoses. The DSM-5 includes stress as a specifier for brief psychotic disorder.) While no model can provide an exact and complete description of clinical disorders, specific factors can be chosen to address all relevant clinical or research purposes.

Clinical Use of a Factor-Based Diagnostic System

To illustrate the use of a factor-based diagnostic system for psychoses, in contrast to the current DSM and ICD categorical systems, we provide a few examples below. In these vignettes, we limit the descriptors to those factors most clearly and specifically related to psychotic disorders, i.e., positive and negative symptoms, mania and depression. These are the consistently observed or consensus factors from past studies. As factors are dimensional, a description of severity is given for each factor; we chose to use mild, moderate, and high. Disorganization is suggested as worth separate monitoring but, for simplicity, we did not include that factor in these vignettes. Stage and course of illness are always essential features [, ], so these are included as factors in the vignettes. Greater detail on stability, recurrence, and improvement or worsening of course can be included, beyond our level of description in these vignettes. Other symptomatic factors, such as anxiety, substance use, and movement disorders, are of value in many cases, but they are not specific to the schizophrenic or affective psychoses, to which this review is targeted. Therefore, we have not included them in these examples. Similarly, it is understood that social factors matter and should be assessed. Again, as they are not specific to the psychoses, they are not included in the examples immediately below. These and any other relevant factors could easily be added, though the descriptions have considerable richness even without more factors being included. The case examples follow.

A Case with Change over Time in Symptoms, as Reflected in Factors, but Not Diagnosis

A 52-year-old man developed behavioral problems as a teenager and then manifested frank psychotic symptoms, both hallucinations and delusions, in his early 20s, at which time he was diagnosed with schizophrenia. Throughout his 20 and 30s, he was hospitalized multiple times after fights with family members over concerns that they were using electromagnetic radiation to control his thoughts and behavior. Over time, these hospitalizations became less frequent and they ceased in his 40s. He has spent the last 10 years in a group home, where he is mostly inactive and keeps to himself. He reports no hallucinations but continuing worries about radiation. His family members say his current state is nothing like what it used to be, but the diagnosis remains schizophrenia. In a factor-based model, he might be diagnosed as having a chronic psychosis, initially with high positive symptoms but recently with moderate positive and high negative symptoms.

Two Cases in Whom the Diagnosis Is the Same, but the Symptoms and Treatment Are Different, with Those Differences Well Described in the Factor Presentation

Two 40-year-old men each have a diagnosis of schizoaffective disorder, bipolar subtype; each was diagnosed at age 20 years. The first man had a series of manic episodes with grandiose and paranoid delusions early in his illness with intervening periods of significant recovery. As the years went by, the manias persisted but became less pronounced and more episodic, while his delusions and hallucinations became more severe, and he became unable to work and live independently. He is currently being treated with a long-acting injectable antipsychotic medication and experiences persistent paranoid delusions which interfere with his relationships. The second man also had a series of manic episodes with ideas of reference, paranoia, and grandiose delusions early in his illness, but he had intervening periods of depression and suicidal ideation and behavior. He has been treated with lithium and an antidepressant for over a decade and his episodes are now under good control. He uses antipsychotic medication as a secondary agent when he notices a worsening of his paranoia and ideas of reference. Both men have schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type. In a factor-based model, the first man has a chronic psychotic illness with high manic and moderate positive psychotic symptoms early in his course and moderate manic and high positive psychotic symptoms later in his course. The second man also has a chronic illness, but with high manic and high positive psychotic symptoms early and high depressive and moderate positive psychotic symptoms later in his course.

A Case with a Series of R/O Diagnoses Persisting over Time versus a Clear and Consistent Set of Factor Descriptors

A 43-year-old woman has been treated since the age of 18 years for recurrent symptoms of depression, including a low mood, a poor appetite, reduced enjoyment of activities, and guilt about her behaviors, accompanied by episodes of irritability, increased self-importance, and concerns that her friends and coworkers are trying to get her hospitalized. She describes stormy interpersonal relationships, periods of difficulty functioning at work, and a series of boyfriends who have left her when she accuses them of being against her. She has been diagnosed with unspecified depressive disorder, with rule-outs for bipolar disorder versus major depressive disorder versus schizoaffective disorder, all of which have persisted in her chart without ever being resolved. Described by factors, she has a chronic illness with moderate depressive symptoms and episodes of moderate manic and moderate positive psychotic symptoms.

A Case of Brief Psychotic Disorder, where Factors More Richly Describe How the Patient Presents

A 35-year-old woman who works as a real estate agent became increasingly agitated over 2 weeks during a period in which she was concerned about competition in closing a major sale. She reported hearing voices of her colleagues, when she was alone at home, criticizing her. She has kept working but started accusing colleagues of scheming to block her progress, was tearful, and complained that this process has made her depressed and pessimistic. She also reported a reduced need for sleep, and a feeling that her sales abilities are far superior to those of anyone else in the office. Her primary care doctor sent her to a psychiatrist who diagnosed a brief psychotic disorder. She responded well to a low dose of antipsychotic medication. In a factor-based model, she is in a first episode of illness, with moderate positive psychotic symptoms, moderate depressive symptoms, and moderate manic symptoms.

As noted, the factors specified in the case vignettes were limited to a few features specific to psychoses. Many other important aspects of illness, not specified in categorical diagnoses, can also be addressed. These include the effects of treatment, which can either ameliorate symptoms or produce new symptoms. Iatrogenic cognitive disruption, movement disorder, and anxiety-agitation, among others, can all be accommodated [, ]. Also, numerous determinants of stress or the combined effects of stress, the cumulative toxic elements of “allostatic load,” can be specified, in one or more factors [, ]. The choice of details would depend on the setting and timing. For an intake, more factors might be involved, including suicidality, anxiety, social elements, and stress load [, , ]. For a routine follow-up visit, selecting key factors describing each patient might be most practical and relevant.

Finally, regarding the practical clinical use of factors, surveys of clinical practices reveal that clinicians already use them [, ]. Specifically, clinicians use the DSM and ICD largely for administrative and clerical purposes, as is required, much less so for treatment guidance. For making therapeutic choices, they assess the syndromic factors that characterize each patient, including the severity of those factors, and address the factors with appropriate interventions, including choices of medications, psychosocial therapies, and site of treatment. This process, not categorization, is typical of much of general medicine [].

Conclusion

Categorical diagnoses, such as those of the DSM and ICD, have played a crucial role guiding clinical decisions and research directions on psychotic disorders. However, the available evidence does not suggest that categories are the primary underlying structure of the psychoses [, ]. The illnesses are inherently dimensional, which is not captured by categories [, ]. Contrary to the essential nature of categories, current DSM and ICD diagnoses lack clear boundaries. Schizophrenia, in particular, has no unique features, not in symptoms, course, or determinants []. The categories in the broader schizophrenia spectrum have neither unique nor unifying features. Similarly, the defining features of affective psychoses and manic and depressive symptoms are shared with schizoaffective disorders and can even appear in schizophrenia [].

That categories remain the standard structural model despite longstanding and growing evidence that a factor-based alternative is a better fit to biological determinants, symptomatic presentations, and clinical practices [, , ] suggests that the value of the factor-based model needs to be clearly summarized. Briefly then, in a factor-based model, patients are individually described by key aspects of their unique presentations, rather than put with others into one or another category, as if all patients with a schizophrenic or affective psychosis were highly alike [, ]. Furthermore, patients can be described in terms of key elements missing from current categorical models, including the stage and social context of their illness []. And factors are dimensional, they reflect severity and change.

In addition to factors, there are other exploratory attempts to more fully and accurately describe psychiatric disorders. Medicine-based evidence (MBE) includes what is known of the biology and biography of individual patients to create a personal narrative to guide precision treatment []. It addresses all the elements that lead to stability (allostasis) or instability (disease) in an individual case. Factor-based models, which can include many elements of a patient’s life circumstances and presentation, are consistent with the MBE approach. Concurrently, hierarchical models are being proposed for classifying psychiatric disorders [, ]. In some ways, hierarchical models are successors to past unitary models of psychiatric disorders. They include a general determinant for risk of all psychiatric illness (P), with various experiences and genes underlying that P []. Other determinants, both inherited and acquired, act on the general background risk to produce a range of specific clinical presentations. All of these determinants fit a “clinimetric” model, i.e., they are measurable, which is a highly desirable trait in characterizing illnesses. Factor-based descriptors fit well with such hierarchical or clinimetric models. In essence, factors are the observable aspects of the clinical presentation that can be incorporated into the hierarchical models or MBE models.

Ultimately, the goal, as stated by Kraepelin, is to model each natural disease as closely as possible [, ]. In cardiology, a myocardial infarction is a clear event with a proximate cause, but cardiovascular disorder predisposing to an myocardial infarction is a heterogeneous condition with complex underlying factors. Treating and studying patients with a cardiovascular disorder requires accounting for the factors of lipid levels and metabolism, inflammation, obesity, and signs of atherosclerosis and heart abnormalities, along with their combinations and interactions. A similar factor-based model may be appropriate for the psychoses. As noted, such factor-based models contain all of the elements in the categorical models but provide further details that distinguish individual patients, reflecting the observed diversity and inherent dimensionality of clinical presentations while still allowing a basis for the grouping and study of patients who share features of illness. Being evidence based and relying on readily available well-documented standard scales [], they achieve the goals of validity, practicality, and utility. Of course, a factor-based model cannot be the last and best model. The factors chosen would be based on confirmed research findings and considerations of specific clinical and research uses. They can be modified as new evidence arises from experience and study. In that way, factor-based models offer an appealing primary model for future versions of the DSM and ICD and for future research on the underlying structure of the psychotic disorders.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Funding Sources

All funding was provided by internal institutional sources.

Author Contributions

All of the authors contributed to the conception, discussion, and production of this review.

References

- 1. Dhaliwal G. Clinical diagnosis-is there any other type?JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(10):1304–5.

- 2. Cohen BM. Embracing complexity in psychiatric diagnosis, treatment, and research. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(12):1211–2.

- 3. Hyman SE. New evidence for shared risk architecture of mental disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):235–6.

- 4. Ripke S, O’Dushlaine C, Chambert K, Moran JL, Kähler AK, Akterin S, et alMulticenter Genetic Studies of Schizophrenia ConsortiumPsychosis Endophenotypes International ConsortiumWellcome Trust Case Control Consortium 2. Genome-wide association analysis identifies 13 new risk loci for schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2013;45(10):1150–9.

- 5. Bramon E, Sham PC. The common genetic liability between schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: a review. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2001;3(4):332–7.

- 6. Laursen TM, Labouriau R, Licht RW, Bertelsen A, Munk-Olsen T, Mortensen PB. Family history of psychiatric illness as a risk factor for schizoaffective disorder: a Danish register-based cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(8):841–8.

- 7. Peralta V, Goldberg X, Ribeiro M, Sanchez-Torres AM, Fañanás L, Cuesta MJ. Familiality of Psychotic Disorders: A Polynosologic Study in Multiplex Families. Schizophr Bull. 2016;42(4):975–83.

- 8. Anttila V, Bulik-Sullivan B, Finucane HK, Walters RK, Bras J, Duncan L, et alBrainstorm Consortium. Analysis of shared heritability in common disorders of the brain. Science. 2018;360(6395):eaap8757.

- 9. Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Electronic address: [email protected] Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Genomic relationships, novel loci, and pleiotropic mechanisms across eight psychiatric disorders. Cell. 2019;179(7):1469–1482.e11.

- 10. Kendler KS. The dappled nature of causes of psychiatric illness: replacing the organic-functional/hardware-software dichotomy with empirically based pluralism. Mol Psychiatry. 2012;17(4):377–88.

- 11. Nesse RM, Stein DJ. Towards a genuinely medical model for psychiatric nosology. BMC Med. 2012;10(1):5.

- 12. Cosgrove VE, Suppes T. Informing DSM-5: biological boundaries between bipolar I disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia. BMC Med. 2013;11(1):127.

- 13. Lawrie SM, O’Donovan MC, Saks E, Burns T, Lieberman JA. Improving classification of psychoses. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(4):367–74.

- 14. Lawrie SM, O’Donovan MC, Saks E, Burns T, Lieberman JA. Towards diagnostic markers for the psychoses. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(4):375–85.

- 15. Jollans L, Whelan R. Neuromarkers for mental disorders: harnessing population neuroscience. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:242.

- 16. Lai MC, Kassee C, Besney R, Bonato S, Hull L, Mandy W, et al Prevalence of co-occurring mental health diagnoses in the autism population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(10):819–29.

- 17. Taylor MJ, Martin J, Lu Y, Brikell I, Lundström S, Larsson H, et al Association of genetic risk factors for psychiatric disorders and traits of these disorders in a Swedish population twin sample. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76(3):280–9.

- 18. Maj M, van Os J, De Hert M, Gaebel W, Galderisi S, Green MF, et al The clinical characterization of the patient with primary psychosis aimed at personalization of management. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):4–33.

- 19. Jablensky A. Psychiatric classifications: validity and utility. World Psychiatry. 2016;15(1):26–31.

- 20. Varatharaj A, Thomas N, Ellul MA, Davies NW, Pollak TA, Tenorio EL, et alCoroNerve Study Group. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: a UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(10):875–82.

- 21. Palm U, Möller HJ. Reception of Kraepelin’s ideas 1900-1960. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2011;65(4):318–25.

- 22. Heckers S, Kendler KS. The evolution of Kraepelin’s nosological principles. World Psychiatry. 2020;19(3):381–8.

- 23. Georgieva L, Rees E, Moran JL, Chambert KD, Milanova V, Craddock N, et al De novo CNVs in bipolar affective disorder and schizophrenia. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23(24):6677–83.

- 24. Singh T, Walters JT, Johnstone M, Curtis D, Suvisaari J, Torniainen M, et alINTERVAL StudyUK10K Consortium. The contribution of rare variants to risk of schizophrenia in individuals with and without intellectual disability. Nat Genet. 2017;49(8):1167–73.

- 25. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421–7.

- 26. Berrios GE, Beer D. The notion of a unitary psychosis: a conceptual history. Hist Psychiatry. 1994;5(17 Pt 1):13–36.

- 27. Maatz A, Hoff P. The birth of schizophrenia or a very modern Bleuler: a close reading of Eugen Bleuler’s ‘Die Prognose der Dementia praecox’ and a re-consideration of his contribution to psychiatry. Hist Psychiatry. 2014;25(4):431–40.

- 28. Kraepelin E. Die erscheinungsformen des Irreseins. Zeitschrift für die gesamte Neurologie und Psychiatrie. 1920;62(1):1-29. Translation in Hoff and Beer. Hist Psychiatry. 1992;93(12):499–529.

- 29. Kendler KS, Engstrom EJ. Criticisms of Kraepelin’s psychiatric nosology: 1896-1927. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(4):316–26.

- 30. Kendler KS. The development of Kraepelin’s concept of dementia praecox: A close reading of relevant texts. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(11):1181–7.

- 31. Kasanin J. The acute schizoaffective psychoses. 1933. Am J Psychiatry. 1994;151(6Suppl):144–54.

- 32. Schneider K. Clinical psychopathology. New York: Grune & Stratton; 1959.

- 33. Leonhard K. The classification of endogenous psychoses. 5th ed ed. New York, NY: Irvington Publishers; 1979.

- 34. First MB, Gaebel W, Maj M, Stein DJ, Kogan CS, Saunders JB, et al An organization- and category-level comparison of diagnostic requirements for mental disorders in ICD-11 and DSM-5. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):34–51.

- 35. Wilson JE, Nian H, Heckers S. The schizoaffective disorder diagnosis: a conundrum in the clinical setting. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2014;264(1):29–34.

- 36. Allardyce J, Suppes T, Van Os J. Dimensions and the psychosis phenotype. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2007;16 Suppl 1(Suppl 1):S34-40.

- 37. Jäger M, Haack S, Becker T, Frasch K. Schizoaffective disorder—an ongoing challenge for psychiatric nosology. Eur Psychiatry. 2011;26(3):159–65.

- 38. Santelmann H, Franklin J, Bußhoff J, Baethge C. Test-retest reliability of schizoaffective disorder compared with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Bipolar Disord. 2015;17(7):753–68.

- 39. Malhi GS, Green M, Fagiolini A, Peselow ED, Kumari V. Schizoaffective disorder: diagnostic issues and future recommendations. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10(1 Pt 2):215–30.

- 40. Guloksuz S, van Os J. The slow death of the concept of schizophrenia and the painful birth of the psychosis spectrum. Psychol Med. 2018;48(2):229–44.

- 41. Lake CR, Hurwitz N. Schizoaffective disorder merges schizophrenia and bipolar disorders as one disease—there is no schizoaffective disorder. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2007;20(4):365–79.

- 42. Carlson GA, Goodwin FK. The stages of mania. A longitudinal analysis of the manic episode. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1973;28(2):221–8.

- 43. Kotov R, Leong SH, Mojtabai R, Erlanger AC, Fochtmann LJ, Constantino E, et al Boundaries of schizoaffective disorder: revisiting Kraepelin. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1276–86.

- 44. Mental health: a report of the Surgeon General. Rockville (MD): National Institute of Mental Health; 1999.

- 45. Perälä J, Suvisaari J, Saarni SI, Kuoppasalmi K, Isometsä E, Pirkola S, et al Lifetime prevalence of psychotic and bipolar I disorders in a general population. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(1):19–28.

- 46. McGorry PD, Bell RC, Dudgeon PL, Jackson HJ. The dimensional structure of first episode psychosis: an exploratory factor analysis. Psychol Med. 1998;28(4):935–47.

- 47. Kassraian-Fard P, Matthis C, Balsters JH, Maathuis MH, Wenderoth N. Promises, pitfalls, and basic guidelines for applying machine learning classifiers to psychiatric imaging data, with autism as an example. Front Psychiatry. 2016;7:177.

- 48. Ruderfer DM, Ripke S, McQuillin A, Boocock J, Stahl EA, Pavlides JM, et alBipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Electronic address: [email protected] Disorder and Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Genomic dissection of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, Including 28 subphenotypes. Cell. 2018;173(7):1705–1715.e16.

- 49. Stephan KE, Bach DR, Fletcher PC, Flint J, Frank MJ, Friston KJ, et al Charting the landscape of priority problems in psychiatry, part 1: classification and diagnosis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(1):77–83.

- 50. Laursen TM, Agerbo E, Pedersen CB. Bipolar disorder, schizoaffective disorder, and schizophrenia overlap: a new comorbidity index. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(10):1432–8.

- 51. Tandon R, Heckers S, Bustillo J, Barch DM, Gaebel W, Gur RE, et al Catatonia in DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(1):26–30.

- 52. Abrams R, Taylor MA. Catatonia. A prospective clinical study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33(5):579–81.

- 53. Peralta V, Cuesta MJ. Exploring the borders of the schizoaffective spectrum: a categorical and dimensional approach. J Affect Disord. 2008;108(1-2):71–86.

- 54. Potuzak M, Ravichandran C, Lewandowski KE, Ongür D, Cohen BM. Categorical vs dimensional classifications of psychotic disorders. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(8):1118–29.

- 55. Service SK, Vargas Upegui C, Castaño Ramírez M, Port AM, Moore TM, Munoz Umanes M, et al Distinct and shared contributions of diagnosis and symptom domains to cognitive performance in severe mental illness in the Paisa population: a case-control study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(5):411–9.

- 56. Ravichandran C, Öngür D, Cohen BM. Clinical features of psychotic disorders: comparing categorical and dimensional models. Psychiatric Research and Clinical Practice; 2020.

- 57. Schildkrout B. How to Move Beyond the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders/International Classification of Diseases. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2016;204(10):723–7.

- 58. Widing L, Simonsen C, Flaaten CB, Haatveit B, Vik RK, Wold KF, et al Symptom profiles in psychotic disorder not otherwise specified. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:580444.

- 59. McGorry PD, Purcell R, Hickie IB, Yung AR, Pantelis C, Jackson HJ. Clinical staging: a heuristic model for psychiatry and youth mental health. Med J Aust. 2007;187S7:S40–2.

- 60. McGorry PD, Nelson B, Goldstone S, Yung AR. Clinical staging: a heuristic and practical strategy for new research and better health and social outcomes for psychotic and related mood disorders. Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55(8):486–97.

- 61. Chouinard G, Samaha AN, Chouinard VA, Peretti CS, Kanahara N, Takase M, et al Antipsychotic-induced dopamine supersensitivity psychosis: pharmacology, criteria, and therapy. Psychother Psychosom. 2017;86(4):189–219.

- 62. Fava GA, Rafanelli C. Iatrogenic factors in psychopathology. Psychother Psychosom. 2019;88(3):129–40.

- 63. Fava GA, McEwen BS, Guidi J, Gostoli S, Offidani E, Sonino N. Clinical characterization of allostatic overload. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019;108:94–101.

- 64. Guidi J, Lucente M, Sonino N, Fava GA. Allostatic load and its impact on health: a systematic review. Psychother Psychosom. 2021;90(1):11–27.

- 65. Currier D, Mann JJ. Stress, genes and the biology of suicidal behavior. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31(2):247–69.

- 66. Young S, Pfaff D, Lewandowski KE, Ravichandran C, Cohen BM, Öngür D. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Psychopathology. 2013;46(3):176–85.

- 67. First MB, Rebello TJ, Keeley JW, Bhargava R, Dai Y, Kulygina M, et al Do mental health professionals use diagnostic classifications the way we think they do? A global survey. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(2):187–95.

- 68. Cohen BM, Ravichandran C, Öngür D, Harris PQ, Babb SM. Use of DSM-5 diagnoses vs. other clinical information by US academic-affiliated psychiatrists in assessing and treating psychotic disorders. World Psychiatry. Forthcoming 2021.

- 69. Fava GA, Rafanelli C, Tomba E. The clinical process in psychiatry: a clinimetric approach. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(2):177–84.

- 70. Kendler KS. Classification of psychopathology: conceptual and historical background. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):241–2.

- 71. Helzer JE, Kraemer HC, Krueger RF. The feasibility and need for dimensional psychiatric diagnoses. Psychol Med. 2006;36(12):1671–80.

- 72. Maier W. Do schizoaffective disorders exist at all?Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(5):369–71.

- 73. Barch DM, Bustillo J, Gaebel W, Gur R, Heckers S, Malaspina D, et al Logic and justification for dimensional assessment of symptoms and related clinical phenomena in psychosis: relevance to DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(1):15–20.

- 74. Heckers S, Barch DM, Bustillo J, Gaebel W, Gur R, Malaspina D, et al Structure of the psychotic disorders classification in DSM-5. Schizophr Res. 2013;150(1):11–4.

- 75. Kawa S, Giordano J. A brief historicity of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: issues and implications for the future of psychiatric canon and practice. Philos Ethics Humanit Med. 2012;7(1):2.

- 76. Reed GM, First MB, Kogan CS, Hyman SE, Gureje O, Gaebel W, et al Innovations and changes in the ICD-11 classification of mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders. World Psychiatry. 2019;18(1):3–19.

- 77. Lobitz G, Armstrong K, Concato J, Singer BH, Horwitz RI. The biological and biographical basis of precision medicine. Psychother Psychosom. 2019;88(6):333–40.

- 78. Krueger RF, Kotov R, Watson D, Forbes MK, Eaton NR, Ruggero CJ, et al Progress in achieving quantitative classification of psychopathology. World Psychiatry. 2018;17(3):282–93.

- 79. Lahey BB, Moore TM, Kaczkurkin AN, Zald DH. Hierarchical models of psychopathology: empirical support, implications, and remaining issues. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):57–63.

- 80. Fried EI, Greene AL, Eaton NR. The p factor is the sum of its parts, for now. World Psychiatry. 2021;20(1):69–70.

- 81. Hoff P. The Kraepelinian tradition. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2015;17(1):31–41.