Introduction

Considering that students with Learning Disabilities (LD) are usually considered vulnerable to experience not only face to face but also online labelling/bullying issues (), it is not surprising that especially amid the period of social distances due to the Covid-19 pandemic unsafe social media use has emerged as an alarming issue among them. Nevertheless, only a significantly limited number of studies has examined this issue on this target population, while almost no study attempts to highlight the underlying emotional and behavioral mechanisms, which could explain the involvement of students with LD in cyberbullying. In this context, the present study aimed to investigate intensity of Facebook use and cyberbullying involvement among elementary school students with LD, as well as the network of the relationships among self-esteem and sense of loneliness (as emotional mechanisms) and the intensity of Facebook use (as behavioral mechanism) which explains their cyberbullying involvement.

Students with LD are children who have been diagnosed by officially established diagnostic services of each country with specific developmental disorders of scholastic skills, including (a) reading disability (dyslexia), (b) writing disability (dysgraphia), and (c) arithmetic disability (dis-numeracy) and are taught by special education teachers for some hours per day at their General Education school (; ). Students with LD, due to their objective difficulties in specific learning domains, their frequent abstention from their general classroom and their classmates (during their teaching by special education teachers), as well as their usually poor academic performance, are often labelled by their peers with typical development and usually end up having poor face to face interpersonal relationships in the school environment (; ; ; ; ). In this context, students with LD could perceive social networking sites as a more flexible and safer virtual environment, where they could make new friends and form interpersonal relationships more easily, compared to the physical school environment where stigmatization issues often arise (; ; ).

Although today there is a variety of social media and online applications (e.g., Instagram, Twitter) easily accessible to youths, younger children, such as elementary school students, and especially those with special educational needs seem to mainly prefer Facebook as a more familiar online interactive environment (; ; ; ; ; ). Compared to other social media platforms, Facebook environment offers users an extra chance to post on their profile more detailed information about themselves, as well as to post messages, photos/videos and/or web links on their online friends’ “walls”. These features, combined with the possibility of creating groups chatting, applications and fan pages make Facebook a platform where mutual social interaction is significantly enhanced in various ways (; ). The above characteristics could explain why Facebook has been recognized as the most popular and attractive social media platform among students before and during the Covid-19 pandemic (; ; ). Furthermore, young children’s preference for Facebook environment could be associated with the usually reported parents’ familiarity with this social media platform (; ). Based on the above reasons, it was assumed that the participating elementary schools students with LD would be more likely to be familiarized with and make use of Facebook. Therefore, the present study focused exclusively on this social media environment, investigating students’ cautious and safe or not pattern of online behavior.

Facebook Use and Cyberbullying among Students with LD

Facebook, as a social networking site with the greatest popularity among youths globally (), has been systematically investigated through common metrics, such as the number of online contacts/friends (; ; ), and the time spent on Facebook (; ; ) by adolescents and adults with typical development. On the contrary, the literature regarding the use of Facebook by students with LD who attend General Education schools is significant limited and reveals contradictory findings that concern almost exclusively secondary school students (; ; ). For example, the available studies, one the one hand, mention adolescents’ average/normal time spent on Facebook (), while on the other hand, other studies confirm that adolescents spend many hours on Facebook daily (; ). Consequently, further investigation is needed in order to identify the pattern of Facebook use adopted by students with LD in General Education elementary schools, where digital literacy is officially integrated into the curriculum (author, 2018, 2020). Furthermore, although Facebook constitutes a highly multidimensional and interactive environment (), the above studies focus only on the frequency and duration of its use, paying little attention on students’ cognitive and emotional perspective on Facebook. Specifically, according to , investigating people’s thoughts and feelings towards the role of Facebook in their daily life (e.g., “Facebook is part of my daily routine”, “I feel like I am part of the Facebook community.” etc.) reflects the intensity of its use, namely the extent to which people perceive Facebook as an integral and necessary part of their daily activity, implying in that way individuals’ possibly less functional use of this platform. Thus, it would be important to be investigated, not only the duration of Facebook use and the number of online friends among elementary school students with LD, but also their cognitive and emotional attitude towards it.

Additionally, students’ timely over-involvement in Facebook activities can gradually blur the boundaries between its safe and unsafe use. Unsafe use of Facebook is usually reflected in a frequently recorded phenomenon, cyberbullying. Cyberbullying constitutes an intentional, aggressive act carried out by an individual or a group of individuals using electronic means of communication, repeatedly and over time, against a victim who cannot easily defend himself/herself (). This phenomenon refers to the dysfunctional use of online services (e.g., chatting, posting) offered on social networking sites, such as Facebook (). In the context of the continuous familiarization of younger and younger children with the internet and social media use (; ; ), even students of the last grade of elementary school are likely to get involved in cyberbullying episodes on Facebook (author, 2022). Although the literature reveals that elementary school students with typical development have been engaged in cyberbullying as bullies and victims in percentages up to 12% and 8%, respectively (e.g., ; ; ; ; ; ) mainly by sending/receiving instant messages on Facebook (; ), the related studies conducted on students with LD are almost absent. The only available studies, concern mainly young adults () or adolescents (; Heiman et al., 2015; ; ), who attend schools of Special Education, due to their severe special educational needs (e.g., severe autistic disorder, intellectual and neurodevelopmental disabilities). However, these findings do not inform about the specific ways in which people with disabilities engage in cyberbullying (as victims/bullies). Furthermore, it remains unanswered what is the pattern of cyberbullying behavior (extent, forms) of elementary school students with milder disabilities (e.g., learning disabilities), as the students of the present study, who attend classrooms in General Education. Filling this literature gap could possibly highlight groups of high-risk students in General Education and subsequently the necessity to implement related school prevention programs.

Furthermore, studies conducted on students with typical development confirm a positive predictive relationship between their use of Facebook and their involvement in cyberbullying incidents as victims and/or bullies (e.g., ; ; ). That is, the more students make use of social media, such as Facebook, the more likely they are to get involved in aggressive online behaviors, such as exerting/experiencing online victimization (; ; ). In other words, it seems that when students spend many hours on Facebook daily, exploring the available applications offered (e.g., chatting, posting), it is likely to develop online communication with known/unknown individuals, in the context of which students can victimize or be victimized by others (author). However, according to the author’s knowledge, the above relationship between the use of Facebook and cyberbullying engagement (as victims/bullies) has not yet been identified for a student population with LD.

Gender Differences in Facebook Use and Cyberbullying among Students with LD

Many studies have investigated gender differences regarding Facebook use and involvement in cyberbullying among students with typical development, concluding in most cases that boys use Facebook and engage in cyberbullying to a greater extent, compared to girls (e.g., ; ; ; ; ; ). This could be associated with the fact that boys usually get acquainted with technological products and online services/applications earlier in their life than girls (; ; ), and consequently boys are more likely to gradually over-engage in social media use (e.g., Facebook) on a daily basis possibly resulting in unsafe online experiences such as cyberbullying (author). In contrast, the related studies conducted on students with LD are significantly limited, leading to inconsistent findings. As far as Facebook use, on the one hand, no gender differences are mentioned among students with LD () while, on the other hand, boys with LD seem to admit that they spend more time on Facebook daily, compared to girls (). Accordingly, the findings regarding cyberbullying do not offer a clear picture. Some studies conclude that girls with LD are involved in this phenomenon (as victims/bullies) more frequently than boys (; ), confirming girls’ tendency to engage (as victims/bullies) in indirect aggressive behaviors, such as relational bullying and cyberbullying (; ). In contrast, more recent studies show no gender differences in exerting or experiencing cyberbullying among students with LD (Didden et al., 2019; Heiman & Olenik- Shemesh, 2015). Considering the above contradictory findings, it is difficult to illustrate a gender-based profile of students with LD at risk for being absorbed by Facebook use and experiencing/exerting cyberbullying.

The Role of Self-esteem and Loneliness in Facebook Use and Cyberbullying among Students with LD

Students with LD, due to their difficulties in different school subjects, usually have a history of school failure, they tend to hold their poor learning skills responsible for their low school performance and perceive their difficulties as permanent (; ; ). Τhis sense of difficulties is usually generalized by students with LD, who tend to believe that they cannot succeed in other domains (e.g., social/interpersonal) in their life as well (; ). As a result, students often end up experiencing a low sense of self-esteem (; ), which refers to the evaluative aspect of themselves (). In the context of this general low self-perspective, students with LD are likely to seek peer support and acceptance even in a virtual environment, such as Facebook (; ; ; ). Considering that in case of students with typical development (without LD) their low self-esteem can positively predict the time they spent on Facebook (; ; ; ), as well as their likelihood of engaging in unpleasant online experiences (as victims/bullies), such as cyberbullying (; ; ), it could be argued that this may holds true especially for students with LD. This lies in the fact that students with LD, due to their labelling issues and the possibly ensuing difficulties in their face to face interpersonal relationships (; ; ; ; ), they are likely to spend time on Facebook daily in an active way (e.g., chatting, posting), perceiving it as an important daily routine (intensity of Facebook use), in order to enhance their likely poor social status in the school context. That way, students with LD face a possibility of being easily involved in conversations with new unknown online friends, which may lead to conflict/disagreement or verbal behaviors representatives of cyberbullying.

Another emotional aspect that seems to be associated with Facebook use and engagement in cyberbullying episodes (as victims/bullies) is people’s sense of loneliness. Loneliness is defined as a cognitive discrepancy between individuals’ desired and experienced social relationships (; ). Based on previous findings on student populations with typical development, it is deducted that students’ sense of loneliness seems to positively predict the time they spent on Facebook (e.g., ; ) as well as their involvement in cyberbullying (e.g., ; ). In other words, when students feel socially distant and lonely, they are more likely to find alternative ways of making social contacts. These ways may include surfing on Facebook daily and making frequent use of its available online interactive services, such as chatting or posting (; ). Also, students who feel lonely are likely to exchange frequent messages with (known/unknown) Facebook friends in the context of which they may engage (as victims/bullies) in unpleasant online experiences, such as cyberbullying (; ). Considering the reported difficulties of students with LD in socializing and making close interpersonal relationships due to likely stigmatization issues (; ), it could be speculated that the positive predictive relationship between sense of loneliness and an unsafe pattern of Facebook use (intensity of its use, engagement in cyberbullying episodes) is also the case for students with LD. Nevertheless, this is yet to be scientifically identified.

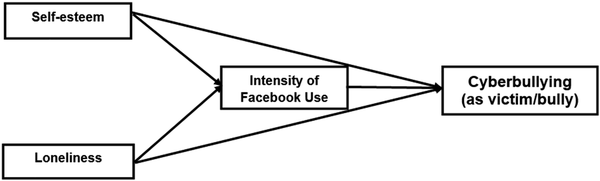

The above findings presented in this section, combined with the positive predictive relationship between use of Facebook and cyberbullying (), could be incorporated into the theoretical framework of Problem Behavior Theory (PBT) (). According to PBT, the development of a problematic behavior, such as cyberbullying, could be resulted from the combination of different systems, such as the personality/emotional (e.g., sense of self-esteem and loneliness) and the behavior system (e.g., intensity of Facebook use) (). Therefore, based on this theoretical perspective, the literature review of the present article could imply an unidentified network of relationships among emotional (self-esteem, sense of loneliness) and behavioral mechanisms (intensity of Facebook use), which could better explain the involvement of students with LD in problematic behavior in cyberspace, such as cyberbullying (as victims or bullies). Specifically, it could be supposed that both students’ self-esteem and sense of loneliness predict their engagement in the phenomenon of cyberbullying, while at the same time intensity of Facebook use moderates the above predictive relationships. This investigation is considered of high importance the current period of the Covid-19 pandemic. This lies in the fact that the social restrictions imposed on many countries worldwide, including Greece, during the last year (; ), have triggered negative feelings (e.g., high sense of loneliness) not only in young adults (; ; ) but also in children and adolescents (). Therefore, examining for the first time this network of relationships, could highlight the need for addressing possible maladaptive emotional issues among students with LD, protecting them in that way from adopting a future dysfunctional pattern of Facebook use.

Purpose, Goals and Hypotheses of the Present Study

Taking into consideration the literature findings and gaps presented in Introduction, the present study aimed to investigate intensity of Facebook use and cyberbullying involvement among elementary school students with LD, as well as the network of the relationships among self-esteem and sense of loneliness (as emotional mechanisms) and the intensity of Facebook use (as behavioral mechanism), which explains the involvement in cyberbullying incidents. Specifically, the research goals of the present study were to investigate among students with LD:

1. The extent to which (a) they make intense use of Facebook, and (b) get involved in cyberbullying incidents (as victims/bullies),

2. The effect of their gender (a) on the intensity of their use of Facebook, and (b) their involvement in cyberbullying incidents (as victims/bullies),

3. The network of the relationships among the variables under study (self-esteem, loneliness, intensity of Facebook use, cyberbullying) that leads to their involvement in cyberbullying incidents (as victims/bullies)

Based on the related literature, the theoretical connection model of the variables of the present study is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Hypothetical structural model of the network of the relationships among variables.

According to the related findings, it is expected that students with LD make intense use of Facebook (Hypothesis 1a) (; ), and get involved (as victims/bullies) in cyberbullying incidents (Hypothesis 1b) (; Heiman et al., 2015; ; ). Furthermore, it is expected that both boys and girls with LD make intense use of Facebook (Hypothesis 2a) (e.g., ), and get involved in cyberbullying (Hypothesis 2b) as victims/bullies (; ). Also, it is expected that self-esteem (; ; ; ) and sense of loneliness of students with LD (; ; ) predict directly (negatively and positively, respectively) their involvement (as victims/bullies) in cyberbullying (Hypothesis 3a). Finally, intensity of Facebook use by students with LD is expected to moderate the relationship between their emotional state (self-esteem, sense of loneliness), on the one hand, and their engagement in cyberbullying (as victims/bullies), on the other hand (Hypothesis 3b) (; ; ; ; ).

Method

Sample

From all the General Education elementary schools in Thessaloniki (Greece) with a special education classroom, where students with LD are taught by a special education teacher specific hours per day (), a randomly number of schools in economically diverse districts were selected for both pilot and main study. In all these Greek elementary schools the same curriculum of special education is followed and the same categories of students with LD attend the special education classrooms (). Thessaloniki is the second largest city in Greece with a student population that is representative of the whole Greek student population and other European countries (Pan-Hellenic School Network, n.d.). Particularly, the pilot sample of the study consisted of 40 sixth-grade students [23 (57.5%) boys, 17 (42.5%) girls] who made Facebook use, coming from nine randomly selected schools which responded to the survey. The students of the pilot sample had been diagnosed in the middle of their elementary education with LD (e.g., dyslexia) by officially established diagnostic services, such as the Educational and Counseling Centers (K.E.S.Y.) of Thessaloniki, which are officially institutionalized centers by the Greek Ministry of Education for the diagnosis of LD in the student population of each prefecture (). The pilot study did not indicate the need to modify the questionnaires. Therefore, the pilot sample was integrated into the sample of the main study (171 new sixth grade students with LD). The main sample was selected from 29 new randomly selected elementary schools, which responded to the survey and were located in economically diverse districts of Thessaloniki. As a result, the total sample consisted of 211 sixth-grade students [119 (56%) boys, 92 (44%) girls)] with LD, who made Facebook use. The mean age of the students was 12.1 years (SD = 2.12). As mentioned in the Introduction, sixth grade students were chosen because during the last grade of elementary education children seem to start making use of Facebook and get involved in cyberbullying episodes (e.g., ; ; ).

Measures

For the present study, a self-reported questionnaire was used. The initial questions concerned students’ demographic characteristics (e.g., gender, age). After this introductory part, three main parts followed:

Facebook Intensity Use Scale: The perceived intensity of Facebook use was measured with the Facebook Intensity Use Scale (), which has been previously translated and used in a sample of Greek adolescents with LD () with good psychometric properties (α = .841). The scale evaluates the use of Facebook including questions and statements that measure, not only the frequency and the duration of its use, but also the extent of students’ active and emotional involvement in the activities of this platform. Specifically, the scale evaluates: (a) the number of friends based on an eight-point scale (from 0 = up to 10 friends to 8 = over 400 friends) and (b) the time is spent on Facebook per day based on a five-point scale (from 0 = up to 10 minutes to 5 = over 3 hours). Also, the scale includes six attitudinal statements designed to tap the extent to which participants are emotionally connected to Facebook and the extent to which Facebook has been integrated into their daily activities (e.g., “Facebook is part of my daily routine activity.”, “I am proud when I tell others that I have Facebook profile too.”). Participants are asked to respond to the statements based on a five-point Likert scale, ranging from (1) = not valid at all to (5) = absolutely valid. The index of Facebook Intensity Use derives from the average of the total score of the questions and the statements, as long as they have been previously converted to standardized z scores due to the differing item scale ranges. Τhe higher the score the higher the perceived intensity of Facebook use.

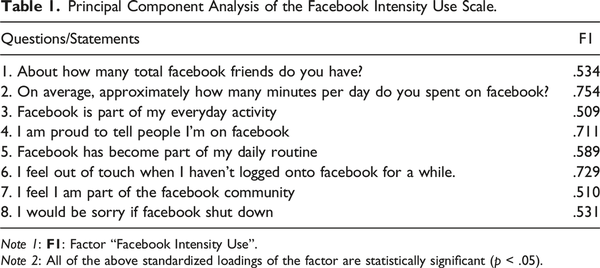

Although the scale has been previously used in Greece by , it was decided to re-test the validity of the scale, as the sample of the present study includes elementary school students and not adolescents. Consequently, a principal component analysis was carried out using the main component method and Varimax-type rotation (KMO = .883, Bartlett Chi-square = 1919.121, p < .001). One factor emerged with eigenvalue >1.0 and significant interpretive value in line with the original structure (Table 1): Factor 1 = Facebook intensity use, explaining 49.59% of the total variance. The internal consistency index for the Factor 1 is α = .871. The affinities (according to Pearson’s correlation coefficient r) of the score of each question of the factor with the sum of the scores of the remaining questions of the factor (corrected item - total correlation) are considered satisfactory: Factor 1 (from r = .44 to r = .51).

Cyberbullying Questionnaire: This questionnaire constitutes a short form of the “Cyberbullying Questionnaire” by , which has been previously translated and used with good psychometric properties (Factor 1: α = .845, Factor 2: α = .821) in a Greek survey conducted on sixth grade elementary school students with typical development (). The original questionnaire consists of 88 multiple choice questions covering seven subcategories of cyberbullying (bullying through text messaging, phone calls, pictures/video-clips, email, chat rooms, instant messaging and websites). Due to the fact that the present study aimed to investigate only some basic parameters of cyberbullying in Facebook environment, the questions were limited to eight. Specifically, the seven initial subcategories of cyberbullying were grouped into four main ways of experiencing cyberbullying (as victims/bullies) on Facebook (e.g., sending messages, spreading rumors, circulating pictures/videos, and making online calls), already reported among elementary school students (author). This grouping is reflected in eight questions, such as the following: “Have you received on Facebook, in the last year, offensive/threatening messages that made you feel bad?”, “Have you spread on Facebook, in the last year, negative rumors or comments about someone to make him/her feel bad?”. The focus of these questions on specific actions (e.g., sending offensive/threatening messages, spreading negative rumors, etc.) and not on general content questions (e.g., “Have you been cyberbullied in the last year?”) lies in the fact that in this way questions are more easily understood by younger children eliciting more realistic responses (). The questions are answered on a five-point scale as follows: 1 = I have not done anything similar/Nothing similar has ever happened to me, 2 = I have done it/It has happened to me one or 2 times, 3 = I have done it/It has happened to me two or 3 times a month, 4 = I do it/It happens to me about once a week, and 5 = I do it/It happens to me several times a week.

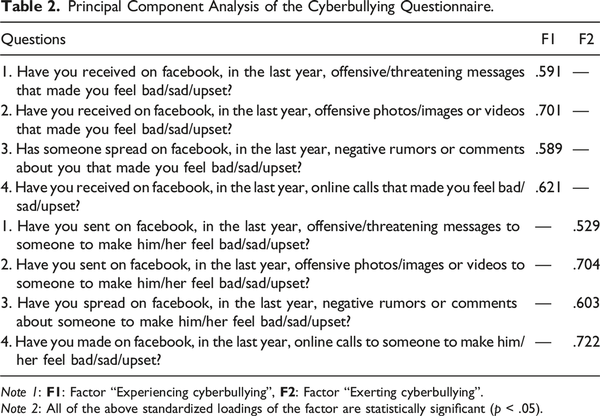

Although the scale has been previously tested psychometrically in Greece (author), the validity of the scale was also examined, as the sample of the present study included students with LD and not with typical development. Specifically, a principal component analysis was performed using the main component method and Varimax-type rotation (KMO = .881, Bartlett Chi-square = 1912.321, p < .001). Two factors emerged in each case with eigenvalue >1.0 and significant interpretive values (Table 2) in line with the structure in case of students with typical development (authors): Factor 1 = Experiencing cyberbullying, explaining 35.23% of the total variance and Factor 2 = Exerting cyberbullying, explaining 29.11% of the total variance. The internal consistency indexes are the following: Factor 1: α = .829 and Factor 2: α = .792. The affinities (according to Pearson’s correlation coefficient r) of the score of each question by the factor with the sum of the scores of the remaining questions of the factor (corrected item - total correlation) are considered satisfactory: Factor 1 (from r = .43 to r = .52) and Factor 2 (from r = .41 to r = .49).

Self-esteem Scale: Students’ self-esteem was examined with the Greek version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (), which has been previously used in a Greek study, conducted on a mixed sample of secondary and elementary school students with and without special educational needs, showing good psychometric properties (α = .810) (). The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale is a widely used scale for measuring global self-esteem, that is, individual’s overall self-evaluation in relation to his/her worth as a human being (). This scale includes 10 items concerning both, positive and negative, proposals/statements about oneself. Individuals are asked to state the extent of their agreement on a four-point Likert scale ranging from (1) strongly disagree to (4) strongly agree. The negative proposals/statements are reverse-scored. The higher the total score of the scale the higher the self-esteem. Examples of the proposals/statements are the following: “Overall I am satisfied with myself”, and “I have a positive self-attitude”.

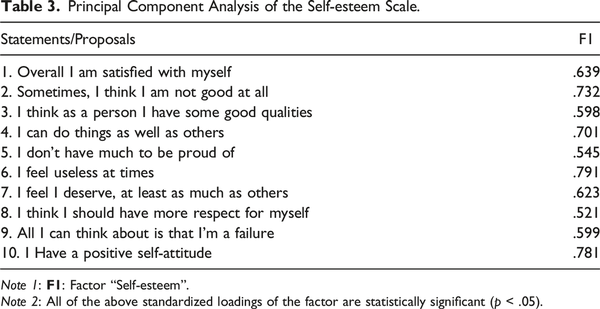

Although the scale has been previously tested psychometrically in Greece (), the validity of the scale was also examined, as the sample of the present study included exclusively elementary school students with LD. To test the validity of the scale, a principal component analysis was carried out using the main component method and Varimax-type rotation (KMO = .881, Bartlett Chi-square = 1498.232, p < .001). One factor emerged with eigenvalue >1.0 and significant interpretive value in line with the original unidimensional structure (Table 3): Factor 1 = Self-esteem, explaining 68.21% of the total variance. The internal consistency indexes for this Factor is α = .884. The affinities (according to Pearson’s correlation coefficient r) of the score of each question by the factor with the sum of the scores of the remaining questions of the factor (corrected item - total correlation) are considered satisfactory: Factor 1 (from r = .41 to r = .59).

Loneliness Scale: Students’ sense of loneliness, that is the cognitive discrepancy between their desired and experienced social relationships, was examined with the Greek version of the short form of the University of California and Los Angeles Loneliness Scale - UCLA-LS (ULS-8; ). The short form of UCLA-LS has been previously used in a sample of Greek university students () with good psychometric properties (α = .834). According to previous studies, there are concerns with the factorial validity of the original 20-item UCLA-LS, indicating that a short-form is also reliable and valid as the original 20-item scale while also displaying superior model fit and reduce the burden on respondents (; ). Furthermore, the choice of the short form of UCLA-LS lies in the fact that an extended scale could trigger to the participating students greater fatigue issues due to their LD. This unidimensional short form of UCLA-LS scale includes eight proposals/statements, for which individuals are asked to state how often they feel as each proposal/statement describes on a four-point Likert scale ranging from (1) = never to (4) = always. Specifically, the scale consists of two positively worded (“I am an outgoing person”, and “I can find companionship when I want it”), which are reverse-scored. The higher the total score of the scale the higher the sense of loneliness. Examples of the proposals/statements are the following: “People are around me but not with me”, “I lack companionship”, and “There is no one I can turn to”.

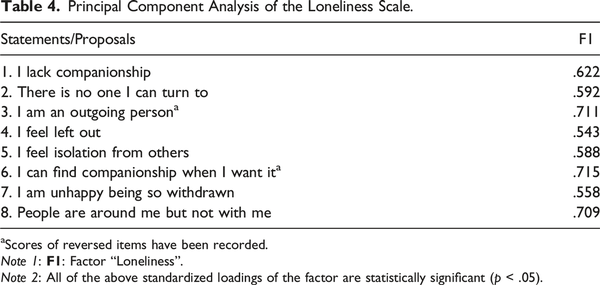

Accordingly to the other scales, although the short form of UCLA-LS scale has been previously tested psychometrically in Greece (), the validity of the scale was also examined, as the sample of the present study included exclusively elementary school students with LD. To test the validity of the scale, a principal component analysis was carried out using the main component method and Varimax-type rotation (KMO = .892, Bartlett Chi-square = 1781.144, p < .001). One factor emerged with eigenvalue >1.0 and significant interpretive value in line with the original unidimensional structure (Table 4): Factor 1 = Loneliness, explaining 65.11% of the total variance. The internal consistency indexes for this Factor is α = .839. The affinities (according to Pearson’s correlation coefficient r) of the score of each question by the factor with the sum of the scores of the remaining questions of the factor (corrected item - total correlation) are considered satisfactory: from r = .35 to r = .45.

Procedure

After the approval for the survey by the Greek Ministry of Education (Protocol No: Φ15/112971/ΖΧ/127172/Δ1, Date: 23/09/2021), the pilot phase of the study took place. An email was sent to 15 General Education elementary schools randomly selected from economically diverse districts of Thessaloniki (Greece). The email included the approval by the Ministry of Education and details about the study and the identity of the researcher (author of the article). Out of the 15 schools, nine from western, eastern, and central areas of Thessaloniki responded positively to the author’s email (response rate 60%). After a positive response from a school, the researcher sent a second email with an attached consent form, asking the school principal and the teacher(s) of the sixth grade to deliver it to parents through the sixth grade students. The consent form included all the necessary information about the study and the identity of the researcher. Additionally, in the consent form parents were asked to mention if their child had been diagnosed with LD in the past by officially established diagnostic services, specifying the diagnostic category of LD (e.g., dyslexia), and if their child has received special education teaching at General Education school. Finally, parents were asked to sign the form in case they consent with their child’s participation in the study. It should be highlighted that before parents’ consent, due to the protection of the students’ personal data, the researcher could not be informed by the school principals about the exact number of the sixth students diagnosed with LD based on school files. Therefore, the researcher did not have a clear picture of the initial number of parents who received the consent form of the study, and subsequently of their response rate. Among the parents who consented (N = 40), only a few (N = 10) mentioned the specific diagnostic category of LD (e.g., dyslexia) of their child. This did not allow the researcher to investigate (applying appropriate statistical analyses) the possible differences regarding the variables under study based on students’ diagnostic category of LD. When the signed consent forms were returned to schools through students, the researcher was invited by the school principal to visit the school and administer the questionnaires to the students. Before the delivery of the questionnaire, the researcher asked the students with LD of each school if they used Facebook through their own or others’ electronic means of communication. All students reported that they made Facebook use. It was speculated that asking the question regarding Facebook use directly to the students and not to their parents through the consent form it could elicit more honest and realistic responses. The participating students (N = 40) completed the questionnaire in the presence of the researcher inside the school but outside their typical teaching classroom, so as not to disrupt the lesson for the rest of the students. During the completion, the researcher offered to students reading assistance, in order to ensure their understanding of the questions/statements. The duration for the completion of the questionnaires was estimated at around 15–20 minutes. The above procedure was also applied in the main phase of the study, where 171 new sixth grade students selected from 29 new randomly selected schools (response rate 52% out of 56 schools). As mentioned in the Sample section, because the pilot study led to no modifications of the questionnaire, the pilot sample (N = 40) was integrated into the main sample (N = 171), resulting in the total sample of students with LD (N = 211). Undoubtedly, parents’ consent and students’ participation were voluntary, while all the criteria of anonymity and confidentiality of the data were met.

Results

Methods of Analyses

Without any missing data, the following statistical methods were used. In order to depict students’ perceived intensity of Facebook use (Hypothesis 1a), their involvement in cyberbullying (Hypothesis 1b), as well as their self-esteem and sense of loneliness descriptive statistic was applied. To test students’ gender effect on their intensity of Facebook use (Hypothesis 2a), one-way ANOVA was carried out, setting gender as independent variable and intensity of Facebook use as dependent variable. To examine students’ gender effect on their involvement in cyberbullying (Hypothesis 2b), a multivariate analyses of variance (MANOVA) was performed, setting gender as independent variable and the two factors of the cyberbullying questionnaire (experiencing/exerting cyberbullying) as dependent variables. To investigate the dyadic relationships among the variables under study (intensity of Facebook use, cyberbullying, self-esteem, sense of loneliness) a series of Pearson (Pearson r) was carried out. Finally, the confirmation of the research Hypotheses 3a and 3b were checked by applying path analyses to the data (using the Mplus program with the Maximum Likelihood method) to depict the network of the relationships among the variables involved (self-esteem, loneliness, intensity of Facebook use, cyberbullying), which leads to the involvement in cyberbullying incidents (as victims/bullies) among students with LD.

Intensity of Facebook Use, Cyberbullying, Self-esteem and Loneliness among Students with LD

Regarding the perceived intensity of Facebook use among students with LD (first research goal) the following were emerged: According to students’ self-reports, 43% of them mentioned that they have 151-200 Facebook friends, 29% have 201-250 Facebook friends, while for 28% of them Facebook friends range from 251 to 300. A far as the time spent on Facebook daily, more than half of the students (59%) admitted that they spent 2–3 hours, while 41% of the students spent more than 3 hours per day. The above findings, combined with the students’ responses on the five-point Likert type questions regarding the extent to which they are emotionally connected to Facebook led to a total score (Mean = 4.03, SD = .48) that reflects a high perceived intensity of Facebook use.

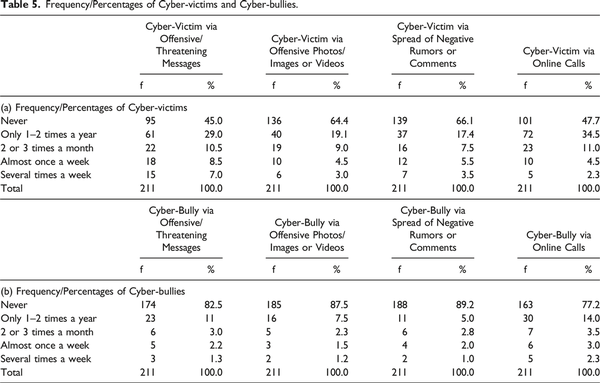

Also, in the context of the first research goal, the frequency of students’ involvement in cyberbullying (as victims/bullies), based on the type of incidents, are shown in Tables 5(a) and (b) respectively. According to Table 5(a), the majority of students stated that they had never been a victim of cyberbullying on Facebook. Regarding those who stated that they have been cyber-victims, for most of them this happened only 1–2 times a year, via online calls (34.5%), offensive/threatening messages (29%), offensive photos/images or videos (19.1%) and spread of negative rumors or comments (17.4%). In contrast, students’ percentages are lower when the frequency of their online victimization increases. For example, the percentages of students who were bullied online from two or 3 times a month to several times a week in the last year range from 3% to 11%, depending on the form of online victimization.

According to Table 5(b), the majority of students stated that they had never bullied others on Facebook. Regarding those who admitted that they have done it, for most of them this happened only 1–2 times a year, mainly via online calls (14%) and offensive/threatening messages (11%). At lower rates, students bullied others on Facebook via offensive photos/images or videos (7.5%) and spread of negative rumors or comments (5%). Students’ percentages are lower when the frequency of cyberbullying statements increase. For example, the percentages of students who bullied others online from two or 3 times a month to several times a week in the last year range from 1% to 3.5%, depending on the form of cyberbullying.

Finally, the students’ total score on the four-point Likert scales of self-esteem and sense of loneliness seems to reflect a relatively low self-esteem (Mean = 1.89, SD = .55) and a high sense of loneliness (Mean = 3.35, SD = .47).

Students’ Gender Effect on Intensity of Facebook Use and Cyberbullying

Concerning the second research goal, the following were emerged: Students’ gender seemed to significantly affect their perceived intensity of Facebook use, F (4, 208) = 9.124, p < .001, partial η2 = .54, with girls making more intense Facebook use (Mean = 4.01, SD = .54) compared to boys (Mean = 3.55, SD = .49). Accordingly, students’ gender seemed to significantly affect their involvement in the phenomenon of cyberbullying, Pillai’s trace = .034, F (4, 207) = 5.231, p < .001, partial η2 = .44, in both cases: experiencing, F (1, 209) = 11.098, p < .001, partial η2 = .52, and exerting cyberbullying, F (1, 209) = 9.124, p < .001, partial η2 = .55. Specifically, it was found that girls with LD experience (Mean = 3.99, SD = .34) and exert cyberbullying (Mean = 3.85, SD = .53) to a greater extent, compared to boys (Mean = 3.43, SD = .51 and Mean = 3.21, SD = .44, respectively).

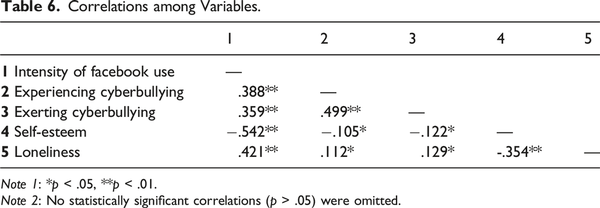

Correlations among Variables

Based on the Table 6, there is a positive correlation between the factors of experiencing and exerting cyberbullying (r = .499, p < .01). Also, there are positive correlations between students’ perceived intensity of Facebook use and experiencing (r = .388, p < .01), on the one hand, and exerting cyberbullying (r = .359, p < .01), on the other hand. In contrast, students’ self-esteem and sense of loneliness seemed to negatively correlate with each other (r = −.354, p < .01). Students’ self-esteem had a negative correlation with their perceived intensity of Facebook use (r = −.542, p < .01), as well as with their involvement in cyberbullying as victims (r = −.105, p < .05), and bullies (r = −.122, p < .05). Finally, students’ sense of loneliness was positively correlated with their online behaviors mentioned above (perceived intensity of Facebook use: r = .421, p < .01, experiencing cyberbullying: r = .112, p < .05, exerting cyberbullying: r = .129, p < .05).

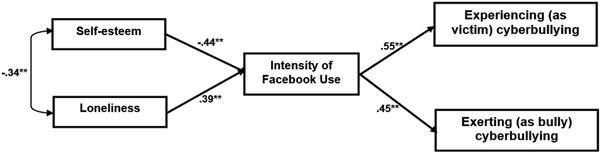

Path Analysis among Variables

Regarding the third research goal, to map the network of the relationships between the variables involved that leads to the students’ involvement in cyberbullying (as victims/bullies), a path analysis was performed. For this purpose, a series of preliminary analyses of linear stepwise regressions was performed to check the predictive relationships between the variables per two. Meeting the assumptions of normality and without any missing cases, the path model that emerged from the students’ responses had good fit indexes for their involvement in cyberbullying: χ2 (84, Ν = 211) = 43.812, p > .05 (CFI = .994, TLI = .922, RMSEA = .065, SRMR = .089) (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Schematic representation of the path model for the students’ involvement in cyberbullying (as victim/bully). Note 1: The values on the arrows are standardized coefficients of the model. The value next to the convex arrow is correlation coefficient. Note 2: **p < .01.

According to Figure 2, students’ perceived intensity of Facebook use seemed to positively predict their involvement in cyberbullying as victims and bullies. Furthermore, the results showed that students’ self-esteem seemed to predict negatively and only in an indirect way their involvement in cyberbullying as victims (Z4 = −3.44, p < .01) and bullies (Z = −3.39, p < .01), through the mediating role of students’ perceived intensity of Facebook use. Accordingly, students’ sense of loneliness seemed to positively predict but only in an indirect way their involvement in cyberbullying as victims (Z = −2.83, p < .01) and bullies (Z = −2.45, p < .01), through the mediating role of students’ perceived intensity of Facebook use.

Discussion

The present study aimed to investigate intensity of Facebook use and cyberbullying involvement among elementary school students with LD, as well as the network of the relationships among self-esteem and sense of loneliness (as emotional mechanisms) and the intensity of Facebook use (as behavioral mechanism), which explains their cyberbullying involvement.

Intensity of Facebook Use and Cyberbullying among Students with LD

According to the findings, more than half of the participating elementary school students with LD (57%) mentioned that they have from 201 to 300 Facebook friends, while 41% of the students spend on Facebook more than 3 hours daily. Furthermore, students admitted to a great extent that Facebook is of high importance in their daily routine and they are emotionally connected to this platform. According to , who developed the Facebook Intensity Use Scale, the above pattern of students’ behavior towards Facebook could imply a generally intense use of this social networking site on a daily basis. This finding confirms Hypothesis 1a and the limited similar studies, which reveal that adolescent students with LD spend many hours on Facebook daily (; ). However, it is worth mentioning that the present finding is in contrast with the study of , who found that Greek adolescents with LD make less intense use of Facebook than their peers without LD. It is likely that the familiarization of younger and younger children with electronic means of communication (e.g., ; ) may explain the participating elementary school students’ high intense of Facebook use. Furthermore, the fact that the present study was conducted during the period of the Covid-19 pandemic in Greece, where restrictions of face to face social interactions were imposed (; ), could have made students perceive Facebook and generally the internet as an integral part of their daily life, making intense use of its available services (e.g., chatting). Nevertheless, considering that students’ use of Facebook usually begins at the end of elementary education (; ), the present finding should be viewed as awakening regarding the participating students’ future pattern of the use of Facebook and social media in general.

Regarding cyberbullying experiences among students with LD, the majority of them have never experienced this phenomenon as victims or bullies. However, a significant part of students with LD admitted that they have victimized others (from 5% to 14% based on the type of bullying) or have been victimized by others (from 17% to 34% approximately based on the type of victimization) once or twice during the last year, while fewer students with LD mentioned that they have been cyber-bullies (from 1% to 3.5%) and cyber-victims (from 3% to 11%) on a more frequent basis (from two or 3 times a month to several times a week). The participating students’ involvement in the phenomenon of cyberbullying (as victims/bullies), even in low percentages, confirms Hypothesis 1b and is in line with other related studies, which show that cyberbullying concerns adolescent students with severe intellectual, autistic and neurodevelopmental disabilities (; Heiman et al., 2015; ; ). The present study shows that younger children with milder disabilities (such as LD) are also involved in unpleasant online experiences, such as cyberbullying. Furthermore, it is implied that the systematically reported bullying experiences in a physical context (e.g., school) among students with mild disabilities (; ; ; , ) are reflected in a virtual environment as well. It could be speculated that the previously reported difficulties of students with LD to form and keep face to face interpersonal relationships with peers due to labelling issues at school (; ; ) could make it easy for them to be rejected, labelled or even victimized, not only in a physical environment but also in cyberspace. Additionally, these social difficulties could make students with LD willing and prone to meet new (possibly unknown) friends in the anonymous and flexible environment of Facebook, where chatting with them could possibly lead students to engage (as victims/bullies) in unpleasant online experiences (e.g., cyberbullying). However, this speculation should be tested statistically in a future related study. Undoubtedly, the participating students’ involvement in cyberbullying, although low in frequency, should alarm families and school authorities regarding future extent of online aggressive experiences among students with LD.

Except for the extent of cyberbullying, the present study informs about the way elementary school students with LD involve in the phenomenon. Specifically, most of the participating students seemed to engage in cyberbullying (as victims/bullies) mainly via offensive/threatening messages and Facebook (online) calls, as it has been previously reported in studies conducted on students with typical development (; author, 2014). This probably implies that, despite the ever-increasing digital literacy during elementary school years (), young children with LD are familiar mainly with usual/common and easily handled ways of online interaction, such as sending instant messages and/or making online calls, just as their peers without LD (, ). It is likely that the circulation of photos/pictures or videos, as another way of experiencing/exerting cyberbullying, constitutes an electronic means of communication that possibly requires higher digital skills, which are reported mostly among adolescents (; ). Also, as mentioned before, the fact that the study was conducted during a period of social restrictions in Greece, due to the Covid-19 pandemic (; ), may account for the students’ less preferred practice of sending/posting photos/pictures or videos as a form of cyberbullying. This predicament could have restricted young children’s activities outside school, where pictures/videos could have been taken and circulated on Facebook in an aggressive way. Additionally, the participating students’ low involvement in spreading negative rumors/comments could be associated with the fact that spreading rumors constitutes a form of relational/indirect bullying, frequently recorded among secondary school students (; ), compared to younger children’s tendency to engage more in direct/verbal bullying, such as offensives/insults (; ).

Students’ Gender Effect on Intensity of Facebook Use and Cyberbullying

In addition, the results revealed that girls with LD make more intense Facebook use and get involved in cyberbullying (as bullies/victims) to a greater extent than boys. This finding rejects Hypothesis 2a and 2b respectively. Also, it is in contrast with the majority of the previous related studies, which mention that gender of adolescent students with LD does not differentiate significantly the time spent on Facebook daily (; ) and the extent of their involvement (as victims/bullies) in cyberbullying incidents (Didden et al., 2019; Heiman & Olenik Shemesh, 2019). However, the present finding is in line with a limited number of studies, which confirm that girls with LD manifest the above online behaviors to a greater extent, compared to boys (; ).

During the last decades, it was argued that in Mediterranean countries, such as Greece, the general technological socialization standards were usually in favor of boys, who were familiarized with technological products (e.g., computers, internet) in the family and school context earlier in their life compared to girls (; ; ). Nevertheless, the present finding implies that the above gender-based picture is likely to be reversed in case of students with LD, as the participating girls with LD seemed to make more intense use of Facebook and get involved in cyberbullying (as victims/bullies), compared to their male peers. Considering the labelling issues that girls with LD may experience at school (; ; ; ) as well as the gender-based stereotypical expectations that girls, compared to boys, temperamentally are more oriented to the formation and maintenance of social relationships (; ; ), it could be argued the following: Girls with LD, in the context of making friendly acquaintances, choose to use the flexible environment of Facebook, where socialization and acceptance could be more easily secured, compared to the physical school environment. Therefore, in this virtual context, girls could be more likely, compared to boys, to get involved in chatting with known/unknown Facebook friends and consequently engage in unpleasant online experiences (as victims/bullies), such as cyberbullying. On the contrary, this pattern of girls’ online behavior (intensity of Facebook use, cyberbullying involvement) is not reported in most studies conducted on students with typical development (; ; ; ). Girls without LD probably are less likely to experience labelling issues and consequently feel to a less extent the need to use an alternative environment for socializing such as Facebook. Nevertheless, in order to make clear whether the pattern of the above online behaviors (intensity of Facebook use, cyberbullying involvement) systematically concerns mainly girls with LD (as the present finding), future comparative related studies conducted on students with and without LD are necessary.

The Role of Students’ Self-esteem and Loneliness in Intensity of Facebook Use and Cyberbullying

Generally, the path analysis results seem to reflect the contribution of both personality/emotional and behavioral mechanisms/systems to the explanation of students’ problematic behaviors even in cyberspace (e.g., cyberbullying), reflecting in that way the framework of PBT ().

Specifically, the path analysis showed that the positive predictive relationship between Facebook use, on the one hand, and involvement in cyberbullying, on the other hand, which has been reported for students with typical development (; ) seems to also be the case for students with LD, confirming Hypothesis 3a. That is, the more the intense the students’ use of Facebook (e.g., using it for many hours daily, perceiving it as an important part of their life, getting emotionally connected with it), the more likely they are to experience (as victims/bullies) episodes of cyberbullying, such as receiving/sending offensive/threatening messages.

Furthermore, the path analysis showed that students’ self-esteem and sense of loneliness negatively predict their involvement in cyberbullying (as victims/bullies), but only indirectly through their perceived intensity of Facebook use. This finding implies the mediating and not the moderating role (as expected according to Hypothesis 3b) of the perceived intensity of Facebook use in the relationship between students’ emotional variables (self-esteem, sense of loneliness) and their involvement in cyberbullying. The fact that students’ current emotional state (self-esteem, sense of loneliness) did not prove to predict directly their involvement in cyberbullying incidents (as victims/bullies) is also associated with the preliminary Pearson’s (Pearson r) relatively low correlations between the emotional variables examined (self-esteem, loneliness), on the one hand, and the two factors of the cyberbullying questionnaire (experiencing/exerting cyberbullying), on the other hand.

In other words, intensity of Facebook use seems to have the potential to totally curb the predictive role of students’ emotional variables in their involvement in cyberbullying (as victims/bullies). That is, it is not necessary that students with LD, who experience low self-esteem and/or a high sense of loneliness, will succumb to the temptation to engage (as victims/bullies) in online aggressive behaviors, such as cyberbullying. A prerequisite for this seems to be students’ extensive time navigation on Facebook and their emotional involvement in its use (pattern of intense Facebook use). Based on previous findings (; ), where students with disabilities admit that they are not very familiarized with social media and its applications, it could be argued the following: Students with LD in order to end up experiencing (as victims/bullies) cyberbullying episodes it is assumed that they are sufficiently familiar with Facebook and its applications. This familiarity may mean students’ long navigation on this platform and therefore their active and possibly emotional involvement in Facebook applications and possibilities (e.g., chatting, posting, sharing). A pattern of behavior indicative of intense Facebook use (). However, this may not be the case for students with typical development, who declare familiarized with social media (), and therefore their possible cyberbullying experiences may occur even in the context of shorter/less intense navigation on Facebook environment. Undoubtedly, this interpretation needs further investigation through future related comparative studies conducted on students with and without LD.

Undoubtedly, the present finding should not be seen as an argument to enhance parental control to reduce Facebook use by students with LD, demonizing social media as a means of communication. On the contrary, it should be viewed as an opportunity of awareness to strengthen students’ safe use of Facebook. Additionally, considering the reported labelling issues in interpersonal relationships among students with LD (; ; ; ; ; ), the social distances imposed on students’ lives worldwide during the period of the Covid-19 pandemic (), as well as the participating students’ emotional state (low self-esteem, high sense of loneliness), concerns are raised regarding the (current) feelings of students with LD and subsequently their future pattern of Facebook use.

Nevertheless, it should be highlighted that the pattern of the relationships among the variables under study (self-esteem, loneliness, intensity of Facebook use, cyberbullying) could not be compared to the previous studies, which mention a direct effect of self-esteem (; ; ), and sense of loneliness on cyberbullying behaviors among students with typical development (; ). The reason lies in the fact that the latter studies have not included the perceived intensity of Facebook use as a moderating or a mediating variable under examination.

Limitations, Future Research and Contribution of the Study

Undoubtedly, the findings of the present study should be interpreted with caution, as they are subject to specific limitations. For example, the restriction of students with LD of a particular city may limit the generalizability of the results, while the fact that the identification of students with LD was based on parents’ self-reports as well as the students’ possibly socially acceptable responses may affect the internal validity of the data. Additionally, the quantitative method followed did not allow for in-depth qualitative investigation of students' relevant experiences. Furthermore, the lack of information about the specific diagnostic category of children’s LD did not allow the examination of the effect of these diagnostic categories (e.g., dyslexia) on the variables studied. These limitations could trigger future relevant studies conducted on a sample of elementary students with LD from other cities as well. A larger sample of this student population would allow the investigation of the statistical effect mentioned before. Additionally, a complementary qualitative investigation of the issue studied, via individual semi-structured interviews or focus groups with students with LD, could better capture their emotional state and their online behaviors examined, possibly highlighting other parameters of this topic. Accordingly, the investigation of parents’ perspective on students’ emotional and online experiences under study could offer a multifaceted approach to the issue. Finally, future comparative studies are necessary, in order to examine whether the proposed network of the relationships among the variables involved is differentiated between students with and without LD, as well as between Facebook and other social media.

Nevertheless, the present study contributes to international related literature. It constitutes a first attempt to capture, based on the theoretical framework of the PBT, the way emotional and behavioral mechanisms explain the involvement of elementary school students with LD in cyberbullying incidents (as victims/bullies). The latter is considered of high importance during the period of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has negatively affected young people’s feelings and the pattern of their social media use (; ; ; ).

The extent of the above emotional (self-esteem, sense of loneliness) and online experiences (intensity of Facebook use, cyberbullying) among students with LD, as well as the way these variables are correlated with each other, offer a significant source of awareness and sensitization for the school community of elementary education (e.g., teachers, parents, mental health professionals), where organized prevention projects and students’ digital literacy are officially integrated into the curriculum (; ). The findings imply that strengthening the emotional state of students with LD and promoting a prudent use of social media (e.g., Facebook) could act protectively in students’ future involvement (as victims/bullies) in unpleasant online experiences, such as cyberbullying. The above could be achieved through prevention actions organized and supervised by counseling and psychological centers, such as K.E.S.Y. in Greece, which are authorized by the Ministry of Education of each country to implement prevention programs in student populations of both General and Special Education for current issues (Jacob et al., 2016; ; Perera-Diltz & Mason, 2008), such as the use of social media and the phenomenon of cyberbullying. For example, school psychologists/counselors and/or elementary school teachers in collaboration with the scientific staff of the counselling and psychological centers could organize mixed group sessions/meetings, consisting of students with and without LD, where through experiential playful activities, such as hypothetical scenarios (), emotional issues could be addressed. The coexistence and cooperation among students with and without LD (or disabilities generally) could contribute to the strengthening of interpersonal relationships, and consequently to the enhancement of self-esteem and to the weakening of the potential sense of loneliness of students with LD. Additionally, implementing prevention actions regarding a safe pattern of social media use and online behaviors in general, such as the project of Threat Assessment Bullying Behavior in Youngsters - TABBY (), is considered beneficial for students with LD as far as their behavior on Facebook. A project like TABBY could focus on specific forms on maladaptive behaviors on Facebook, such as offensive messages and online calls that were mostly reported among the participating students. Finally, given the current period of the Covid-19 pandemic and the distance learning, the above proposed prevention actions could also be delivered online through the school educational platforms. In this case, parents could also be part of these actions, provided that they have been previously informed and trained by the scientific staff of the counselling and psychological centers ().

Conclusion

In summary, the present study informs about the pattern of behavior displayed on Facebook by elementary school students with LD, who attend General Education classrooms. Specifically, the study shows that these students, and mainly girls, make intense Facebook use and engage in cyberbullying episodes (as victims/bullies), mainly via threatening/offensive messages and online calls. Furthermore, based on the PBT, the study depicts for the first time the pattern of the relationships among emotional and behavioral mechanisms/systems that explain students’ online problematic behavior, such as involvement in cyberbullying (as victims/bullies). Particularly, it is concluded that students’ self-esteem and sense of loneliness can predict (negatively and positively respectively) indirectly their engagement in cyberbullying, through the intensity of their Facebook use.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Notes

1 From this point on and for the rest of the present article learning disabilities will be mentioned as LD.

2 In Greece students’ attendance in elementary school lasts 6 years ().

3 In a sample of 300 and 600 people, loadings of more than .29 and .21, accordingly, are accepted ().

4 Ζ = standardized normal distribution value.

References

- Abdulkader W. F. A. K. (2017). The effectiveness of a cognitive behavioral therapy program in reducing school bullying among a sample of adolescents with learning disabilities. International Journal of Educational Sciences, 18(1-3), 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/09751122.2017.1346752

- Aizenkot D., Kashy-Rosenbaum G. (2019). Cyberbullying victimization in WhatsApp classmate groups among Israeli elementary, middle, and high school students. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(15-16), NP8498–NP8519. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519842860.

- Archer C., Kao K.-T. (2018). Mother, baby and Facebook make three: Does social media provide social support for new mothers? Media International Australia, 168(1), 122–139. https://doi.org/10.1177/1329878X18783016

- Aslan H. (2016). Traditional and cyber bullying among the students with special education needs (Master’s thesis), Middle East Technical University).

- Baldry A. C., Farrington D. P., Blaya C., Sorrentino A. (2018). The tabby online project: The Threat assessment of bullying behaviours online approach. In International perspectives on cyberbullying (pp. 25–36). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barasuol J. C., Soares J. P., Castro R. G., Giacomin A., Gonçalves B. M., Klein D., Cardoso M. (2017). Untreated dental caries is associated with reports of verbal bullying in children 8-10 years old. Caries Research, 51(5), 482–488. https://doi.org/10.1159/000479043

- Barlett C. P., Gentile D. A., Chng G., Li D., Chamberlin K. (2018). Social media use and cyberbullying perpetration: A longitudinal analysis. Violence and Gender, 5(3), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1089/vio.2017.0047

- Bates C., Terry L., Popple K. (2017). Supporting people with learning disabilities to make and maintain intimate relationships. Tizard Learning Disability Review, 22(1), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLDR-03-2016-0009

- Bayraktar F., Gün Z. (2007). Incidence and correlates of internet usage among adolescents in north Cyprus. CyberPsychology & Behavior 10(2), 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2006.9969

- Beran T. N., Tutty L. (2002). Children's reports of bullying and safety at school. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 17(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F082957350201700201

- Bergagna E., Tartaglia S. (2018). Self-esteem, social comparison, and Facebook use. Europe's Journal of Psychology, 14(4), 831–845. https://doi.org/10.5964%2Fejop.v14i4.1592

- Błachnio A., Przepiorka A., Rudnicka P. (2016). Narcissism and self-esteem as predictors of dimensions of Facebook use. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 296–301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.11.018.

- Bos H. M., Sandfort T. G., De Bruyn E. H., Hakvoort E. M. (2008). Same-sex attraction, social relationships, psychosocial functioning, and school performance in early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 44(1), 59–68. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0012-1649.44.1.59

- Bourdas D. I., Zacharakis E. D. (2020). Evolution of changes in physical activity over lockdown time: Physical activity datasets of four independent adult sample groups corresponding to each of the last four of the six COVID-19 lockdown weeks in Greece. Data in Βrief, 32, 106301. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dib.2020.106301.

- Brailovskaia J., Margraf J. (2019). I present myself and have a lot of Facebook-friends-Am I a happy narcissist!? Personality and Individual Differences, 148, 11–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.022.

- Brewer G., Kerslake J. (2015). Cyberbullying, self-esteem, empathy and loneliness. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 255–260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.01.073.

- Brough M., Literat I., Ikin A. (2020). “Good social media?”: Underrepresented youth perspectives on the ethical and equitable design of social media platforms. Social Media + Society, 6(2), 2056305120928488. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F2056305120928488

- Bu F., Steptoe A., Fancourt D. (2020). Loneliness during a strict lockdown: Trajectories and predictors during the COVID-19 pandemic in 38,217 United Kingdom adults. Social Science & Medicine, 265, 113521. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113521.

- Campbell M. A., Whiteford C., Duncanson K., Spears B., Butler D., Slee P. T. (2020). Cyberbullying bystanders: Gender, grade, and actions among primary and secondary school students in Australia. In Developing safer online environments for children: Tools and policies for combatting cyber aggression (pp. 113–129). IGI Global.

- Carollo A., Bizzego A., Gabrieli G., Wong K. K. Y., Raine A., Esposito G. (2020). I’m alone but not lonely. U-shaped pattern of perceived loneliness during the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK and Greece. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.26.20239103

- Carrington S., Campbell M., Saggers B., Ashburner J., Vicig F., Dillon-Wallace J., Hwang Y. S. (2017). Recommendations of school students with autism spectrum disorder and their parents in regard to bullying and cyberbullying prevention and intervention. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 21(10), 1045–1064. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1331381

- Cavioni V., Grazzani I., Ornaghi V. (2017). Social and emotional learning for children with Learning Disability: Implications for inclusion. International Journal of Emotional Education, 9(2), 100–109.

- Chapman J. W. (1988). Learning disabled children’s self-concepts. Review of Educational Research, 58(3), 347–371. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00346543058003347

- Chester K. L., Spencer N. H., Whiting L., Brooks F. M. (2017). Association between experiencing relational bullying and adolescent health‐related quality of life. Journal of School Health, 87(11), 865–872. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12558

- Christensen C. A. (2018). Learning disability: Issues of representation, power, and the medicalization of school failure. In Perspectives on learning disabilities (pp. 227–249). Routledge.

- Cosden M., Elliott K., Noble S., Kelemen E. (1999). Self-understanding and self-esteem in children with learning disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 22(4), 279–290. https://doi.org/10.2307%2F1511262

- Coviello J., DeMatthews D. E. (2021). Failure is not final: Principals’ perspectives on creating inclusive schools for students with disabilities. Journal of Educational Administration, 59(4), 514–531. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEA-08-2020-0170.

- Cunha Jr F. R. D., van Kruistum C., van Oers B. (2016). Teachers and facebook: Using online groups to improve students’ communication and engagement in education. Communication Teacher, 30(4), 228–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2016.1219039

- DePaolis K., Williford A. (2015). The nature and prevalence of cyber victimization among elementary school children. In Child & Youth Care Forum pp. 377–393. Springer US.

- Didden R., Scholte R. H., Korzilius H., De Moor J. M., Vermeulen A., O’Reilly M., Lancioni G. E. (2009). Cyberbullying among students with intellectual and developmental disability in special education settings. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 12(3), 146–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/17518420902971356

- Dimogiorga P., Syngollitou E. (2015). The relationship of learning disabilities with the use of social networking websites. Scientific Annals-School of Psychology AUTh, 11, 1–22.

- Ditchfield H. (2020). Behind the screen of Facebook: Identity construction in the rehearsal stage of online interaction. New Media & Society, 22(6), 927–943. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1461444819873644

- Doğan T., Çötok N. A., Tekin E. G. (2011). Reliability and validity of the Turkish Version of the UCLA Loneliness Scale (ULS-8) among university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 2058–2062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.04.053.

- Duimel M., de Haan J. (2007). New links in the family. Den Haag.

- Eagly A. H. (1987). Reporting sex differences. American Psychologist, 42(7), 756–757. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.42.7.755

- Ellison N. B., Steinfield C., Lampe C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x.

- Elmer T., Mepham K., Stadtfeld C. (2020). Students under lockdown: Assessing change in students’ social networks and mental health during the COVID-19 crisis. PLoS ONE, 15(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337.

- Ernala S. K., Burke M., Leavitt A., Ellison N. B. (2020). How well do people report time spent on facebook? An evaluation of established survey questions with recommendations. In Proceedings of the 2020 CHI Conference on human Factors in computing systems (pp. 1–14).

- Ezzatibabi M., Ghasemi G. (2021). Comparison of Self-control with bullying-victim behavior in students with and without learning disability. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 10(3), 92–104.

- Facebook (2021). Facebook statistics you need to know in 2021. Retrieved from https://www.oberlo.com/blog/facebook-statistics

- Fardiah D. (2021). Anticipating social media effect: Digital literacy among Indonesian adolescents. Educational Research (IJMCER), 3(3), 206–218.

- Field A. (2005). Discovering statistics using SPSS (2nd ed.). SAGE.

- Frison E., Eggermont S. (2016). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review, 34(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0894439314567449

- Galanis P. A., Andreadaki E., Kleanthous E., Georgiadou A., Evangelou E., Kallergis G., Kaitelidou D. (2020). Determinants of psychological distress during the COVID-19 pandemic and the lockdown measures: A nationwide on-line survey in Greece and Cyprus. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.10.25.20219006.

- Gibbs S. J., Elliott J. G. (2020). The dyslexia debate: Life without the label. Oxford Review of Education, 46(4), 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1747419

- Giovazolias T., Malikiosi-Loizos M. (2016). Bullying at Greek universities: An empirical study. In Cowie H., Myers C.-A. (Eds.), Bullying among university students: Cross-national perspectives (pp. 110–126). Routledge.

- Goldberg A., Grinshtain Y., Amichai-Hamburger Y. (2021). Caregiving strategies, parental practices, and the use of Facebook groups among Israeli mothers of adolescents. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2021-3-9

- Gradinger P., Strohmeier D., Spiel Ch. (2010). Definition and measurement of cyberbullying. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 4(2), article 1.

- Greenhow C. (2011). Youth, learning, and social media. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 45(2), 139–146. https://doi.org/10.2190%2FEC.45.2.a

- Griffiths M. D. (1995). Technological addictions. Clinical Psychology Forum, 76, 14–19.

- Gurney P. W. (2018). Self-esteem in children with special educational needs. Routledge.

- Hadiatul R., Ashabul M. (2020). The impact analysis of facebook on the education patterns of elementary school children. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1539, 012046. https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1539/1/012046.

- Hashim S., Masek A., Abdullah N. S., Paimin A. N., Muda W. H. N. W. (2020). Students’ intention to share information via social media: A case study of COVID-19 pandemic. Indonesian Journal of Science and Technology, 5(2), 236–245.

- Haura A. T., Ardi Z. (2020). Student’s self esteem and cyber-bullying behavior in senior high school. Jurnal Aplikasi IPTEK Indonesia, 4(2), 89–94.

- Hays R. D., DiMatteo M. R. (1987). A short-form measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 51(1), 69–81.

- Heiman T., Olenik-Shemesh D. (2015). Cyberbullying experience and gender differences among adolescents in different educational settings. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(2), 146–155. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0022219413492855

- Jenaro C., Flores N., Frías C. P. (2018). Systematic review of empirical studies on cyberbullying in adults: What we know and what we should investigate. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 38, 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.12.003.

- Jessor R. (2001). Problem-behavior theory. In Raithel J. (Ed.), Risikoverhaltensweisen jugendlicher (pp. 61–78). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Joinson A. N. (2008). Looking up, looking at or keeping up with people? Motives and use of facebook. In Proceedings of the twenty-sixth annual SIGCHI conference on Human factors in computing systems (pp. 1027–1036). Association for Computing Machinery Press.

- Kantas A. (1995). Group processes-conflict-development and change-culture-occupational stress [in Greek]. Ellinika Grammata.

- Kavale K. A., Forness S. R. (1996). Social skill deficits and learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29(3), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F002221949602900301

- Keshavarz Afshar H., Javaheri A., Ghazinejad N. (2020). Identifying the quality of friendship in students with learning disabilities. Counseling Culture and Psychotherapy, 11(41), 91–116. https://doi.org/10.22054/qccpc.2020.47742.2231

- Kokkiadi M., Kourkoutas I. (2016). School bullying/victimization, self-esteem and emotional difficulties in children with and without SEN [in Greek]. Scientific Annals of the Pedagogical Department of Preschool Education of the University of Ioannina, 9(1), 88–128.

- Kowal M., Sorokowski P., Sorokowska A., Dobrowolska M., Pisanski K., Oleszkiewicz A., Zupančič M. (2020). Reasons for facebook usage: Data from 46 countries. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00711.

- Kowalski R. M., Fedina C. (2011). Cyber bullying in ADHD and asperger syndrome populations. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(3), 1201–1208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rasd.2011.01.007

- Lai H. M., Hsieh P. J., Zhang R. C. (2019). Understanding adolescent students’ use of facebook and their subjective wellbeing: A gender-based comparison. Behaviour & Information Technology, 38(5), 533–548. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2018.1543452

- Larrañaga E., Yubero S., Ovejero A., Navarro R. (2016). Loneliness, parent-child communication and cyberbullying victimization among Spanish youths. Computers in Human Behavior, 65, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.08.015.

- Lazonder A. W., Walraven A., Gijlers H., Janssen N. (2020). Longitudinal assessment of digital literacy in children: Findings from a large Dutch single-school study. Computers & Education, 143, 103681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.103681.

- Lei H., Mao W., Cheong C. M., Wen Y., Cui Y., Cai Z. (2019). The relationship between self-esteem and cyberbullying: A meta-analysis of children and youth students. Current Psychology, 39, 830–842. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00407-6.

- Lenhart A., Madden M. (2007). Social networking websites and teens: An overview. Pew Internet and American Life Project.

- Leontari A. (1996). Self-perception [in Greek]. Ellinika Grammata.

- Li Q. (2006). Cyberbullying in schools: A research of gender differences. School Psychology International, 27(2), 157–170. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0143034306064547

- Lin S., Liu D., Niu G., Longobardi C. (2020). Active social network sites use and loneliness: The mediating role of social support and self-esteem. Current Psychology, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00658-8.

- Little C., DeLeeuw R. R., Andriana E., Zanuttini J. (2020). Social inclusion through the eyes of the student: Perspectives from students with disabilities on friendship and acceptance. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 69(6), 2084–2093. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2020.1837352.

- Liu G., Zhao Y. (2021). Research on the social media use and educational strategies of youth in a Chinese 3rd tier city. In 7th international conference on Humanities and social science research (2021, pp. 793–796). ICHSSRAtlantis Press.