Introduction

Survival has improved among patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), but RA is still associated with increased mortality [], mainly caused by ischaemic heart disease and lung disease[, ]. Pulmonary involvement in RA is common, and respiratory symptoms should lead to considerations concerning a range of differential diagnoses, such as infection, drug toxicity, and pulmonary manifestations of RA itself, that is, interstitial lung disease (ILD). Moreover, bronchiectasis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are common in RA [], and smoking is a major risk factor for RA as well as for RA-ILD and other lung diseases [].

ILD is a serious complication leading to increased morbidity and mortality [, ]. RA-ILD is identified in 2–10% of patients with RA [, , ]. The reported differences in survival and clinical characteristics probably reflect the heterogeneity of the disease. RA-ILD often shares clinical features with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), which is the most common and most serious of the idiopathic ILDs. The approach to IPF treatment changed following the introduction of antifibrotic therapies [, ]. The potential role of antifibrotic therapies in other subtypes of fibrosing ILDs, including RA-ILD, is currently investigated in clinical trials [, ].

The aim of the present study was to describe the disease course and clinical predictors of mortality and to assess the presence of progressive fibrosing ILD in a well-characterised, population-based cohort of patients with RA-ILD.

Materials and Methods

We identified patients diagnosed with RA-ILD at the Center for Rare Lung Diseases, Aarhus University Hospital, between 2004 and 2016. The department is the ILD referral centre for the Central Denmark Region with a population of 1.3 million inhabitants (2017). Follow-up data were included until 2017 and were retrieved from patients’ medical records. The Danish Patient Safety Authority approved the study (record number 3-3013-1581/1).

Data Analysis

The cohort was described according to the distribution of gender, age, pulmonary function, radiological findings, seropositivity and selected comorbidities. Mortality risks were assessed using Kaplan-Meier mortality curves with date of first visit as time of origin. We used Cox proportional hazards regression to estimate hazard rate ratios (HRRs) for death with 95% confidence intervals (CI) and computed crude HRRs and HRRs adjusted for age, diffusion capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLco), high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) pattern, and titre of IgM rheumatoid factor (RF). The assumption of the proportional hazards was assessed graphically. We used the Fleischner Society IPF diagnostic guidelines for identification of usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) on HRCT [] and the definition of progressive fibrosing ILD recently suggested by an international group of ILD experts: a relative forced vital capacity (FVC) decline ≥10%, relative DLco decline ≥15% or worsening symptoms or a worsening radiological appearance accompanied by a ≥5 to <10% relative decrease in FVC within a period of 24 months [].

All analyses were performed using STATA statistical software (version 12.1; StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

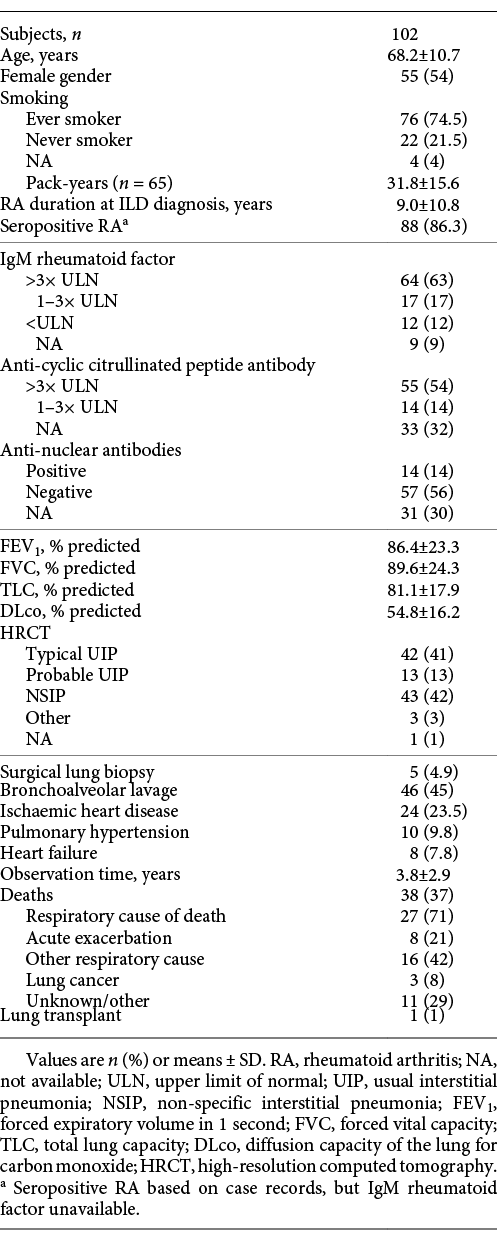

We identified 102 patients with RA-ILD; mean observation time was 3.8 years and median survival was 7.1 years. The annual number of referred patients increased steadily during the study period (2004–2005: 4 patients, 2016–2017: 21 patients).

Positive IgM RF was seen in 86% of the patients. Positive anti-CCP antibodies were seen in 55 patients (54%) equivalent to 80% of those with available measurements. Clinical characteristics are shown in Table 1. Seventy-five percent of the patients had previously received Methotrexate or did so at referral, and 22% of the patients had previously received biological therapy or did so at referral. Corticosteroids were the preferred treatment for ILD and were used in 44% of the patients. Fifty-four percent of the patients did not receive specific ILD-directed therapy within the first year of follow-up. FVC and DLco were significantly lower among patients who received ILD-directed therapy within the first year after ILD diagnosis compared to patients who were followed without ILD-directed therapy (mean FVC 79.4 vs. 97.6% predicted [p = 0.0002] and DLco 48.0 vs. 60.3% predicted [p = 0.0002]), but no significant difference in survival was seen between the 2 groups (HRR 0.59, 95% CI 0.28–1.21). Fifty-seven percent (28/49) of patients who remained stable according to the described criteria and 51% (27/53) of the patients with disease progression did not undergo ILD-directed therapy (p = 0.39).

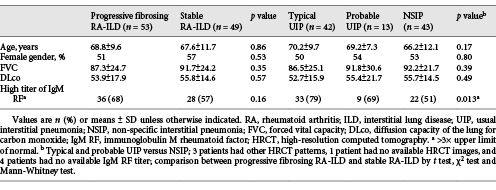

Thirty-seven percent of the patients (38/102) died during follow-up, and 71% of deaths were caused by respiratory disease. Twenty-one percent (8/38) of deaths were caused by acute exacerbation of ILD, and the majority of these (6/8) occurred within the first year of follow-up. Six patients who died from exacerbations of ILD had a typical UIP pattern on HRCT, 1 patient had a probable UIP pattern, and 1 patient had a non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) pattern. FVC, DLco, gender and age were comparable between patients with typical UIP, probable UIP and NSIP (Table 2). The main difference was a higher proportion of patients with high titres of IgM RF among patients with a UIP compared to a NSIP pattern.

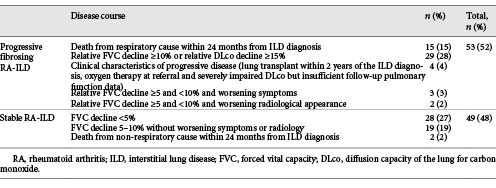

Progressive Fibrosing ILD

Progressive fibrosing ILD was seen in 52% of the patients (53/102), and the remaining 48% (49/102) were considered stable or had improved. Two patients who died of non-respiratory causes within the first 24 months of follow-up were considered stable with regard to ILD. No significant differences were found between patients with progressive and stable disease (Table 2). The distribution of causes of progressive disease is shown in Table 3. Two-year mortality was 4.4% in patients with stable disease and 28.6% in patients with progressive disease; 5-year mortality was 18.7 and 55.0%, respectively.

Fourteen patients experienced improved pulmonary function at 2-year follow-up defined as a 10% increase in FVC and/or a 15% increase in DLco without a significant decline in FVC or DLco. Five patients who improved had a definite UIP pattern, 4 patients had a probable UIP pattern, and 5 patients had an NSIP pattern. Five patients (36%) received no ILD-directed therapy; the remaining 9 patients received oral corticosteroids, Medrol pulse therapy, Azathioprine and/or Mycophenolate.

Thirty-five patients were stable without significant improvement in pulmonary function. Six patients had a definite UIP pattern, 5 had a probable UIP pattern, and 24 had an NSIP pattern.

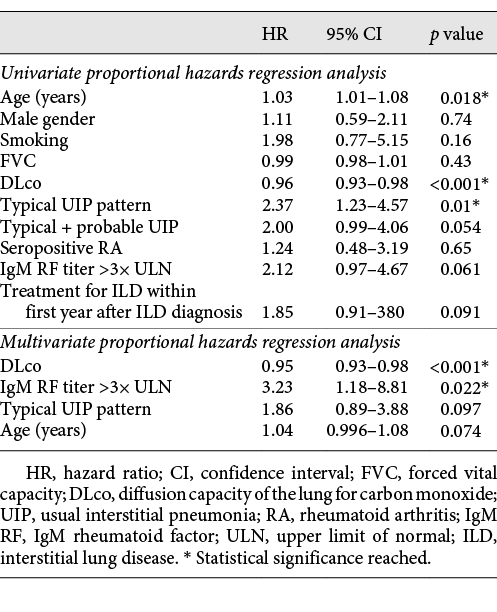

In a univariate proportional hazards regression model, only DLco, HRCT pattern and age significantly impacted on outcome with respect to mortality. In a multivariate proportional hazards regression model, the impact of HRCT pattern was not significant when adjusted for age, DLco and titres of IgM RF (Table 4). In the adjusted analysis, the titre of IgM RF was a significant predictor of mortality. DLco remained a significant predictor of mortality in the adjusted analysis.

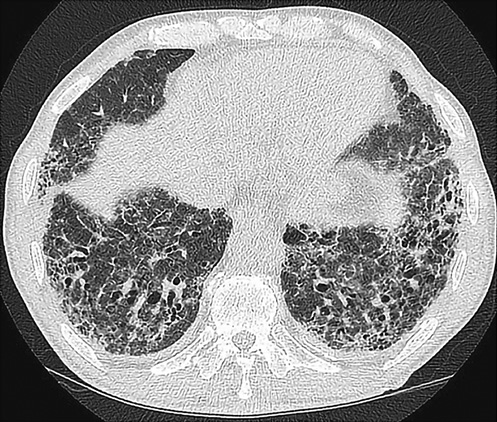

Figures 1 and 2 show HRCT patterns of definite UIP and NSIP.

Fig. 1

Definite UIP pattern on HRCT.

Fig. 2

NSIP pattern on HRCT.

Discussion

ILD is a serious complication of RA, but the reported frequency is variable and disease characteristics are heterogeneous. In a previous study from our group based on national registry data, we found that only 2% of patients with RA had a diagnosis of ILD []. Survival among these patients was significantly impaired compared to patients with RA without ILD. The RA-ILD cohort in the present study, conducted at an ILD referral centre (1 of 3 in Denmark), constitutes 15% of the national registry-based RA-ILD cohort described previously. Interestingly, age and gender distribution were similar in the 2 studies (mean age 68.2 vs. 68.5 years and 54 vs. 55% female patients), and median survival was also comparable (7.1 vs. 6.6 years). The proportion of patients with RA-ILD followed up at ILD specialist centres is unknown, but the number of referred patients to our ILD centre increased markedly during the study period. This may reflect increased use of CT during the study period, but probably also increased awareness of ILD.

Previous studies have reported UIP as the predominant radiological pattern and predictor of mortality [, ]; however, recent studies report a proportion of UIP of 40–54%, which is comparable to our findings [, ]. Better diagnostic strategies and earlier diagnosis before progression to clear-cut UIP may be part of the explanation. A recent study showed that radiology-based prediction models in RA-ILD can identify patients with a progressive fibrosis phenotype [], and visual extent of ILD and FVC values, as previously shown for scleroderma[], predicts outcome in RA-ILD. Our study showed that typical UIP is a predictor of mortality in univariate analysis, though not significant when adjusting for age, DLco and high titres of IgM RF. Similarly, Morisset et al. [] showed that the addition of HRCT pattern to the ILD-GAP prediction model did not improve its performance, and Solomon et al. [] showed that pulmonary physiology independently predicted mortality, but baseline HRCT pattern did not. It is well known that the risk of ILD is higher in seropositive RA with a possible confounding effect of smoking. Our study showed that high titres of IgM RF are an independent risk factor for death when controlling for other potentially influential variables. High titres of IgM RF are frequent in progressive fibrosing RA-ILD and in the presence of a UIP pattern.

The present study confirms that disease behaviour in RA-ILD is heterogeneous and often unpredictable. A minority of the patients experienced a significant improvement in pulmonary function, even in the presence of a UIP pattern. Pulmonary function levels at the time of ILD diagnosis did not show differences between patients who developed progressive disease and those who remained stable, although DLco was a highly significant predictor of mortality.

The management of RA-ILD and other fibrosing ILDs may be subject to change if ongoing studies will show beneficial effects of antifibrotic therapies. Based on recently suggested criteria in progressive fibrosing ILD, 52% of our RA-ILD patients fell into this category and respiratory mortality was high. This underlines the need for evidence-based therapies for progressive fibrosing RA-ILD.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by The Danish Patient Safety Authority (record number 3-3013-1581/1). According to Danish legislation, permission from the Scientific Ethical Committee was not required, as the study did not involve contact with patients or an intervention.

Disclosure Statement

C.H. received a post-doctoral research grant from the Danish Rheumatism Association. T.E., O.H. and E.B. declare no competing interests.

Funding Sources

C.H. received a post-doctoral research grant from the Danish Rheumatism Association.

Author Contributions

C.H., E.B., O.H. and T.E. conceived the study idea. C.H. collected the data and performed the initial analyses. These were developed further by the other co-authors. C.H., T.E., E.B. and O.H. reviewed the literature and participated in the discussion and interpretation of the results. C.H. organised the writing and wrote the initial draft. All authors critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content and approved the final version before submission. C.H. is the guarantor.

References

- 1. Lacaille D, Avina-Zubieta JA, Sayre EC, Abrahamowicz M. Improvement in 5-year mortality in incident rheumatoid arthritis compared with the general population-closing the mortality gap. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(6):1057–63.

- 2. Young A, Koduri G, Batley M, Kulinskaya E, Gough A, Norton S, et alEarly Rheumatoid Arthritis Study (ERAS) group. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Increased in the early course of disease, in ischaemic heart disease and in pulmonary fibrosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(2):350–7.

- 3. Hyldgaard C, Hilberg O, Pedersen AB, Ulrichsen SP, Løkke A, Bendstrup E, et al A population-based cohort study of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: comorbidity and mortality. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(10):1700–6.

- 4. Hyldgaard C, Bendstrup E, Pedersen AB, Ulrichsen SP, Løkke A, Hilberg O, et al Increased mortality among patients with rheumatoid arthritis and COPD: A population-based study. Respir Med. 2018;140:101–7.

- 5. Svendsen AJ, Junker P, Houen G, Kyvik KO, Nielsen C, Skytthe A, et al Incidence of Chronic Persistent Rheumatoid Arthritis and the Impact of Smoking: A Historical Twin Cohort Study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(5):616–24.

- 6. Koduri G, Norton S, Young A, Cox N, Davies P, Devlin J, et alERAS (Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study). Interstitial lung disease has a poor prognosis in rheumatoid arthritis: results from an inception cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2010;49(8):1483–9.

- 7. Zamora-Legoff JA, Krause ML, Crowson CS, Ryu JH, Matteson EL. Patterns of interstitial lung disease and mortality in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2017;56(3):344–50.

- 8. Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Sprunger DB, Fischer A, Fernandez-Perez ER, Solomon J, et al Rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease-associated mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(3):372–8.

- 9. Kelly CA, Saravanan V, Nisar M, Arthanari S, Woodhead FA, Price-Forbes AN, et alBritish Rheumatoid Interstitial Lung (BRILL) Network. Rheumatoid arthritis-related interstitial lung disease: associations, prognostic factors and physiological and radiological characteristics—a large multicentre UK study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2014;53(9):1676–82.

- 10. Noble PW, Albera C, Bradford WZ, Costabel U, Glassberg MK, Kardatzke D, et alCAPACITY Study Group. Pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (CAPACITY): two randomised trials. Lancet. 2011;377(9779):1760–9.

- 11. Richeldi L, du Bois RM, Raghu G, Azuma A, Brown KK, Costabel U, et alINPULSIS Trial Investigators. Efficacy and safety of nintedanib in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(22):2071–82.

- 12. Behr J, Neuser P, Prasse A, Kreuter M, Rabe K, Schade-Brittinger C, et al Exploring efficacy and safety of oral Pirfenidone for progressive, non-IPF lung fibrosis (RELIEF) - a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group, multi-center, phase II trial. BMC Pulmonary Medicine 2017 Sep 6;17(1):122-017-0462-y.

- 13. Flaherty KR, Brown KK, Wells AU, Clerisme-Beaty E, Collard HR, Cottin V, et al Design of the PF-ILD trial: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled phase III trial of nintedanib in patients with progressive fibrosing interstitial lung disease. BMJ Open Respiratory Research 2017 Sep 17;4(1):e000212-2017-000212. eCollection 2017.

- 14. Lynch DA, Sverzellati N, Travis WD, Brown KK, Colby TV, Galvin JR, et al Diagnostic criteria for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a Fleischner Society White Paper. Lancet Respir Med. 2018;6(2):138–53.

- 15. Cottin V, Hirani NA, Hotchkin DL, Nambiar AM, Ogura T, Otaola M, et al Presentation, diagnosis and clinical course of the spectrum of progressive-fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. European Respiratory Review : an official journal of the European Respiratory Society 2018 Dec 21;27(150):10.1183/16000617.0076. Print. 2018;2018(Dec):31.

- 16. Kim EJ, Elicker BM, Maldonado F, Webb WR, Ryu JH, Van Uden JH, et al Usual interstitial pneumonia in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2010;35(6):1322–8.

- 17. Morisset J, Vittinghoff E, Lee BY, Tonelli R, Hu X, Elicker BM, et al The performance of the GAP model in patients with rheumatoid arthritis associated interstitial lung disease. Respir Med. 2017;127:51–6.

- 18. Jacob J, Hirani N, van Moorsel CHM, Rajagopalan S, Murchison JT, van Es HW, et al Predicting outcomes in rheumatoid arthritis related interstitial lung disease. The European Respiratory Journal 2019 Jan 3;53(1):. Print 2019 Jan.

- 19. Goh NS, Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Copley SJ, Maher TM, et al Interstitial lung disease in systemic sclerosis: a simple staging system. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(11):1248–54.

- 20. Solomon JJ, Chung JH, Cosgrove GP, Demoruelle MK, Fernandez-Perez ER, Fischer A, et al Predictors of mortality in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2016;47(2):588–96.