Introduction

Many individuals in the early stages of psychosis experience deficits in social and occupational function, resulting in significant social and economic costs. Despite the availability of psychosocial interventions that improve functioning, a major barrier to developing more effective interventions is accurate measurement. In comparison to symptom measures (eg, SAPS/SANS, and PANSS), there is little consensus about the gold standard for measuring function. There is significant variability in the approach to measurement; while some measures combine different aspects of functioning into a global aggregate score, others assess a single aspect of function. A previous review on functioning measures used in schizophrenia research highlighted the degree to which existing measures differed in terms of number and types of domains covered, and scoring systems. These differences underline the need to evaluate commonly used measures in terms of their sensitivity to differences between groups and changes in function over time.

Currently, global measures, such as the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) and the Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS), are most widely used. While the GAF has been widely used due to its ease of administration, its ability to accurately detect changes in function is questionable. Problems regarding the psychometric properties of measures such as the GAF and SOFAS have been reported. In particular, social and occupational functioning are reported to vary independently of one another, suggesting a need to consider both aspects of function separately. For example, Niv et al found that separating GAF scores into social, occupational, and symptom scores (the “MIRECC” GAF) significantly improved validity metrics. As a result, evaluating global vs specific approaches to measuring function is likely to be informative about measure sensitivity.

The main aims of this review were to (1) gather information about the functioning measures most frequently used in the literature, and (2) evaluate the utility of functioning measures. Utility was determined on the basis of effect sizes for differences/changes in function and the ability of different types of measures to: (a) differentiate between groups in cross-sectional case-control studies; (b) to detect changes in function longitudinally in psychosis cases; and (c) to detect changes in function in response to intervention. Here, we aimed to determine if the largest effect sizes were observed on more global estimates of function or on more specific measures of social function. Our rationale was to explore whether measures combining different aspects of functioning into a global aggregate score were more or less sensitive to change than measures assessing a single aspect of function.

Methods

Study Selection

Both cross-sectional and longitudinal observational and intervention studies of early psychosis (defined as ≤5 years since diagnosis) that included functioning as an outcome measure (either primary or secondary) were considered. Definitions of first-episode and early psychosis vary significantly in the literature; using a cutoff of being within 5 years of first diagnosis allowed us to obtain a balance between including a sufficient number of papers in the review while ensuring the participants included represented the early stages of illness vs more chronic stages. For meta-analyses, cross-sectional studies included studies of early psychosis vs healthy controls (between-group statistics). Longitudinal studies that provided functioning measure scores for early psychosis groups at 2 time points (ie, baseline and follow-up assessment; within-subject statistics) were included. These were included provided baseline assessment occurred within 5 years of a first episode of psychosis. For the purposes of providing a brief and concise summary of the most widely used functioning measures given the large amount of literature considered, only measures that were reported in at least 5 publications were included. All articles that provided the necessary change or comparison statistics for meta-analysis were included.

Search Strategy

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) guidelines. An electronic search was conducted using PubMed and PsycINFO. Search terms are provided in supplementary section S1. Keywords were searched in titles, abstracts, and indexed terms. Searches were limited to English language peer-reviewed articles published between January 2000 and March 2021. Additional articles were identified by searching the references of retrieved articles and reviews.

Data Extraction and Management

Titles and abstracts of articles were screened, following which full-text articles were assessed for eligibility for inclusion in the systematic review and subsequent meta-analyses by 3 independent reviewers (T.W., E.G., and M.C.). Data were extracted for functioning measures, as well as study and participant characteristics (follow-up length, age, percent male, diagnoses, medication use, study setting/service). Discrepancies were resolved by consensus (T.W., E.G., M.C., and G.D.). A record of reasons for exclusion was maintained at each step of the review process (identification, screening, and eligibility assessment). Throughout the review, data were recorded and maintained (T.W., E.G., and M.C.) in standardized data extraction spreadsheets for measure scores/statistics, study/participant characteristics, and for quality assessment checklists.

Quality Assessment

A quality evaluation scale revised from previous studies,, to evaluate relevant indicators of quality for this review was used to rate each study on the following criteria: (1) the sample was representative of the target population (diagnosis based on well-established clinical diagnostic manuals), (2) description of sample size calculations and/or power analysis, (3) reporting of effect sizes relating to the main findings, (4) inclusion of estimates of variability (standard error, standard deviation, or confidence intervals), and (5) inclusion of a description of early psychosis criteria. Each item scored 1 point if the criterion was met, and the overall quality score was calculated by summing items.

Review of Functioning Measures and Data Analysis

While 36 measures of function were identified, only those reported on in at least 5 publications were included in our more detailed review. For meta-analyses, pooled standardized mean difference (SMD—Cohen’s d) was estimated with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software (CMA), Version 3. Effect sizes were pooled using random-effects models. Fisher’s r-to-z conversion was used for variance stabilization and normalization. Meta-analyses were carried out in 3 steps. Firstly, for cross-sectional studies we estimated the effect sizes for differences between healthy control groups and early psychosis groups on functioning measures, based on pooled SMD. Raw means and standard deviations were included in the analysis. Overall pooled SMD for studies was estimated, and separate subgroup analyses were carried out for individual functioning measures where possible, although the small number of studies included for each measure was limited and therefore these analyses should be considered exploratory.

Secondly, to estimate the ability of functioning measures to detect differences in functioning for early psychosis groups over time we compared SMDs between baseline and follow-up scores for longitudinal observational (ie, noninterventional studies) studies. This analysis included studies with short-term follow-up lengths of 6 months, to long-term follow-up lengths of up to 5 years. CMA allows for the inclusion of different data formats in the same analysis. Most studies provided raw data (baseline and follow-up means and standard deviations and baseline-follow-up correlation, or raw mean difference and standard error/confidence intervals) with associated t value or P value. Where raw data were unavailable, estimates of effect size such as Cohen’s d or odd ratios with confidence intervals were used. Overall combined SMD for studies was estimated, and subgroup analyses were performed to compare effect sizes based on type of functioning measure, in particular to compare the GAF to other global measures of function, and to more specific measures of social function and NEET (not in education, employment, or training) status. We classified global measures as those that combine different elements of functioning into an overall aggregate score. Only 2 longitudinal studies were available for NEET status so this should be considered exploratory. Although multiple follow-up time points are reported for some studies, relevant data for meta-analysis was typically only available for 1 time point included in the main analysis of the study. Where relevant data for meta-analysis were available for more than 1 follow-up time point, the time point with the largest sample size was included.

Finally, for intervention studies, to estimate the ability of functioning measures to detect differences in functioning for early psychosis groups following intervention, we compared SMD between intervention and control groups for pre- and postintervention scores. This analysis included studies with short-term duration of 3 months to long-term duration of up to 2 years. For continuous variables, where possible, raw data (pre and post means and standard deviations) were used to estimate effect sizes. Where raw data were unavailable, sample size and F statistics were used. A small number of studies provided dichotomous variables or chi-square statistics for NEET status. Overall combined SMD for studies was estimated, and subgroup analyses were performed to compare effect sizes based on type of functioning measure as above.

Further Subgroup Analyses and Meta-regression

To further evaluate the differences in effect sizes due to type of functioning measure given the variability across studies, we carried out subgroup comparisons and meta-regression analyses where possible. Potential confounding variables of interest included study characteristics (length of follow-up, sample size, treatment setting), participant characteristics (diagnosis: FEP vs early psychosis, and nonaffective psychosis vs mixed diagnosis), and (for intervention studies) intervention type and control condition. Following comparisons in subgroup analyses, confounding variables were entered in a meta-regression as covariates to control for the potential influence on the effect of measure type on effect sizes. CMA allows the evaluation of the effect of 1 variable (in this case type of functioning measure) on effect sizes, while holding other possible confounding variables constant.

Heterogeneity and Publication Bias

Heterogeneity was explored using the Q statistic and the I2 statistics. The Q statistic measures the dispersion of all effect sizes about the mean effect size, the I2 statistic measures the ratio of true variance to total variance. Publication bias was examined by visual inspection of funnel plots, the trim-and-fill method and the regression test.

Results

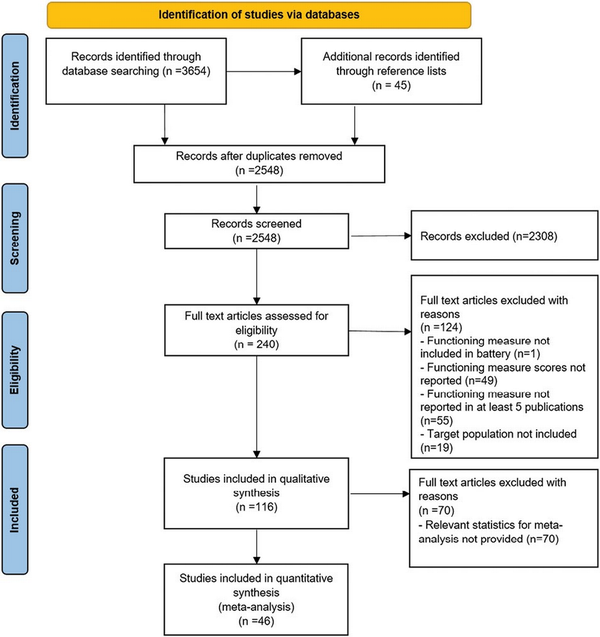

Study Characteristics

A PRISMA flow diagram is presented in figure 1. One hundred and sixteen studies (18, 647 participants) were included in our narrative review and 46 studies (6527 patients and 6734 healthy control participants) were included in our meta-analysis. Study characteristics are presented in supplementary table 2.

Fig. 1

PRISMA flow diagram.

Participants’ mean age ranged from 16.2 to 37.8 years (mean = 24.6, SD = 3.6). Mean percentage of male participants across studies was 64.8%. Seventy-seven studies included 1 functioning measure, 32 studies included 2 measures of function, 4 studies included 3 measures, and 3 studies included 4 measures. Follow-up periods ranged from 3 months to 10 years; 26 included follow-ups of less than 1 year, 23 included follow-ups of 1 year, 30 included follow-ups between 1 and 5 years, 9 included follow-ups of 5–9 years, and 3 included follow-ups of 10 years. Studies included in the meta-analysis for estimating effect sizes of change in function over time (comparing change in scores from baseline to follow-up assessment) and in response to intervention included longitudinal studies with follow-up length ranging from 3 months to 4 years. Sixteen studies had follow-up lengths of less than 6 months, 11 studies had follow-up lengths between 6 months and 1 year, and 10 had follow-up lengths of greater than 1 year. Follow-up length for each study included in meta-analyses is provided in the forest plots.

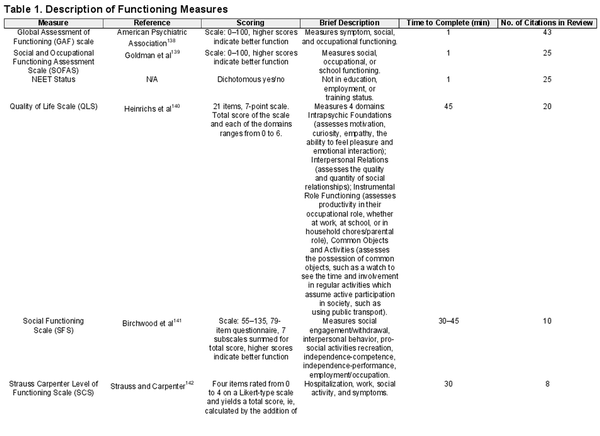

Description of Measures Identified in the Literature

Descriptions of all functioning measures identified in our review are provided in table 1., This table includes measures that were not reported on in <5 publications (n = 26), but are included here to provide a comprehensive overview of the large number and variation of measures used in the literature.

Our search identified 10 measures reported on in 5 or more publications. The most commonly used measures of function were the GAF (N = 43), SOFAS (N = 25), NEET status as a measure of function (N = 25), Quality of Life (QOL) (N = 20), Social Functioning Scale (SFS) (N = 10), Strauss-Carpenter Scale (SCS) (N = 8), Time-use Survey (TUS) (N = 7), Global Functioning Scale (GFS) (N = 6), Role Functioning Scale (RFS) (N = 6), and Functional Assessment Screening Tool (FAST) (N = 5). The measures identified can be broadly categorized as (1) global measures of function (ie, GAF, SOFAS, QOL, SFS, SCS, TUS, GFS total score, RFS total score, FAST), (2) more specific measures of social function (MIRECC GAF social scale, RFS social scale, GFS:social scale), or (3) occupational function (NEET status, MIRECC GAF occupational scale, GFS:role scale). Measures differ in level of detail, and elements of functioning that are assessed. For a more detailed description of the most commonly used measures and a summary of their psychometric properties, please see supplementary section S1.

Methodological Quality

The quality of each study was assessed using a quality evaluation scale. The scores ranged from 2 to 5 points (higher scores indicating higher quality—see supplementary table 3). All but 11 studies confirmed diagnosis using well-established clinical diagnostic manuals (DSM-IV/ICD-10). Only 19 studies reported performing sample size calculations and/or power analysis. Other methodological issues included poor description of first-episode psychosis criteria (we included studies with early psychosis samples of up to 5 years duration of illness due to this issue) and not providing mean scores, standard deviations, or effect sizes for the functioning measures included. The information needed for our meta-analysis was not reported in the majority of studies. For example, studies may have reported functioning scores in baseline characteristics, but no useable data were reported for follow-up. This suggests a lack of reporting of basic findings and study characteristics.

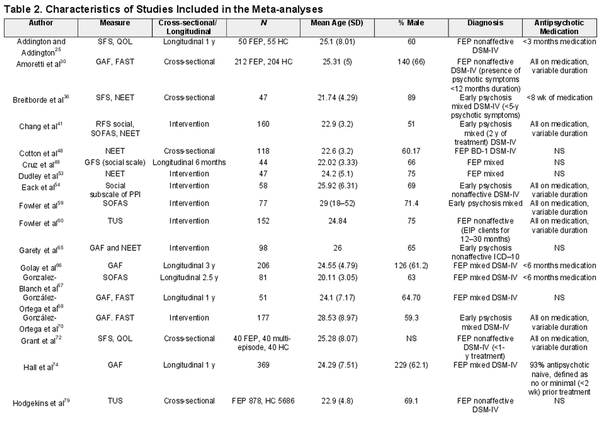

Meta-analyses

Characteristics for studies included in the meta-analysis are presented in table 2. Meta-analyzed results for cross-sectional studies comparing patients and healthy controls, longitudinal studies of early psychosis and intervention studies for which relevant data could be ascertained are presented in figures 2–4 based on the total effect size observed and the effect sizes for subgroups of functioning measure type where these could be estimated. A combined analysis for longitudinal and intervention studies in early psychosis groups is presented in figure 5.

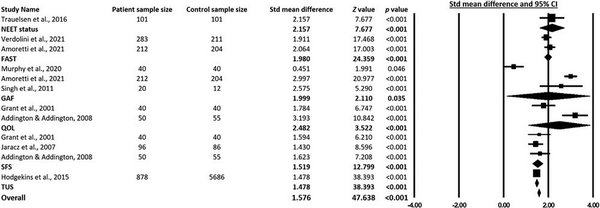

Fig. 2

Sample size, mean difference, and associated forest plots of measures for differences in function between healthy control vs patients.

Significant heterogeneity was noted for cross-sectional, longitudinal, and intervention studies (see supplementary tables 4–6). No evidence of significant publication bias was observed for cross-sectional or longitudinal studies, however publication bias was noted for intervention studies (see supplementary figures 1–3).

Differences Between Healthy Controls and Early Psychosis Groups

Nine cross-sectional studies reported relevant data for patient and healthy control group comparisons (see figure 2). The overall effect size was large (SMD = 1.576, 95% CI [1.511–1.641], P < .001), indicating that measures are generally able to detect differences in functioning between patients and healthy controls. Across the measures included, SMDs ranged from 1.478 to 2.482. For individual measures, the largest effect sizes were observed for QOL (SMD = 2.482, 95% CI [1.101–3.864], P < .001) and NEET status (mean difference = 2.157, 95% CI [1.607–2.708], P < .001), although the limited number of studies involved (2 QOL studies and 1 NEET status study were included) prevented definite conclusions being drawn about these analyses.

Change in Function Over Time in Early Psychosis Groups

Fifteen longitudinal studies allowed a comparison between baseline and follow-up assessment scores for patients with early psychosis (see figure 3). For these studies, medium effect sizes were observed (SMD = 0.490, 95% CI [0.314–0.667], P < .001), suggesting that overall functioning measures are able to detect to changes in functioning over time.

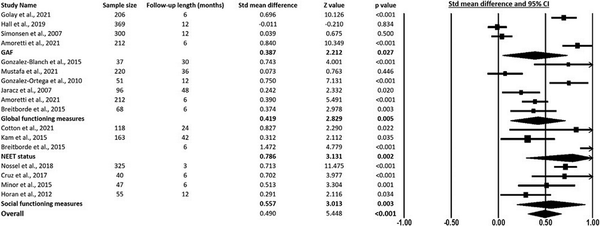

Fig. 3

Sample size, mean difference, and associated forest plots of measures for change in function in early psychosis groups over time.

For comparison between measures, a series of subgroup analyses were conducted separately for the measures most widely used—ie, the GAF scale, NEET status (not in employment, education, or training), other global assessments of social and occupational functioning (considered as a group), and specific measures of social function (considered as a group). Of the global measures most frequently used, the GAF showed smallest effect sizes for changes in function over time (SMD = 0.387, 95% CI [0.044–0.729], P = .027), in comparison specific measures of social function showed a larger effect size for change over time (SMD = 0.557, 95% CI [0.195–0.919], P = .003). Notably, among the brief measures considered, NEET status (SMD = 0.786, 95% CI [0.294–1.277], P < .001) showed a larger effect size for change than longer, more global measures of social and occupational functioning (SMD = 0.419, 95% CI [0.129–0.710], P = .005). However, the NEET group was only used in 3 longitudinal studies and 1 study had a significantly larger effect size which was driving the overall large effect size observed.

Change in Function in Response to Intervention in Early Psychosis Groups

Twenty-five intervention studies allowed a comparison of change in functioning scores in response to intervention in early psychosis (see figure 4). For these studies, medium effect sizes were observed (SMD = 0.319, 95% CI [0.219–0.420], P < .001), suggesting that measures can detect changes in functioning in response to intervention.

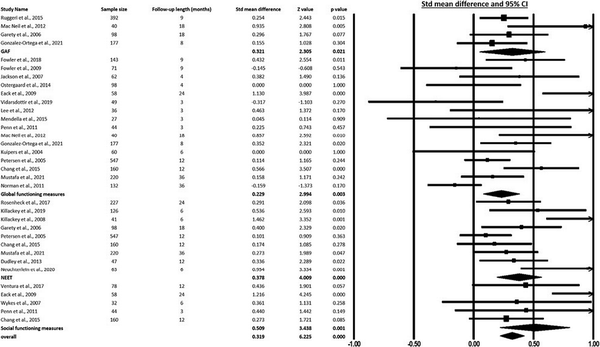

Fig. 4

Sample size, mean difference, and associated forest plots of measures for change in function in early psychosis groups in response to intervention.

For comparison between measures, a series of subgroup analyses were conducted separately for measures most widely used—ie, the GAF, NEET status (considered as a group), other global assessments of social and occupational functioning (considered as a group) and specific measures of social function (considered as a group). Of the measures most frequently used, the global measures group (SMD = 0.229, 95% CI [0.079–0.379], P = .003) and the GAF (SMD = 0.321, 95% CI [0.048–0.594], P = .021) showed the smallest effect sizes for change in function. Specific measures of social function showed the largest effect size (SMD = 0.509, 95% CI [0.219–0.799], P = .001). Notably, among the brief measures considered, NEET status (SMD = 0.378, 95% CI [0.193–0.563], P < .001) showed larger effect sizes than longer, more global measures of social and occupational functioning. For global measures, we re-analyzed the group for studies that included the SOFAS as a separate group from other global measures, given this was included in 6 studies. When this was analyzed as a separate group, the effect size for the global group remained relatively similar (SMD = 0.241, 95% CI [0.041 to 0.441], P = .018), however the effect size for the SOFAS measure was nonsignificant (SMD = 0.215, 95% CI [−0.023 to 0.452], P = .077).

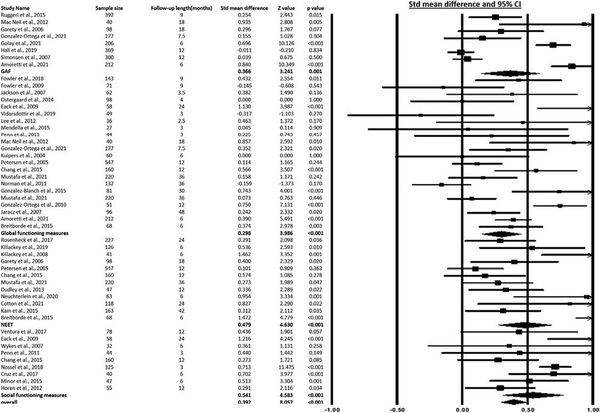

Combined Analyses of Longitudinal and Interventional Studies Combined

Given the comparable effects sizes observed for longitudinal studies and intervention studies, we re-analyzed these data based on all studies combined to maximize the power available for evaluating individual tests. Thirty-seven were included in this analysis. Again, medium effect sizes were observed for the overall sample (SMD = 0.392, 95% CI [0.297–0.488], P < .001). The smallest effect sizes were observed for the global measures group (SMD = 0.298, 95% CI [0.152–0.445], P = .001) and the GAF (SMD = 0.366, 95% CI [0.145–0.588], P = .021). Specific measures of social function (SMD = 0.541, 95% CI [0.309–0.772], P < .001) and NEET status (SMD = 0.479, 95% CI [0.276–0.681], P < .001) showed the largest effect sizes (see figure 5). When the SOFAS measure was analyzed as a separate group, the effect size for the global group (SMD = 0.316, 95% CI [0.131–0.502], P = .001) and SOFAS group (SMD = 0.269, 95% CI [0.029–0.509], P = .028) was comparable.

Fig. 5

Sample size, mean difference, and associated forest plots of measures for change in function in early psychosis groups (combined analysis).

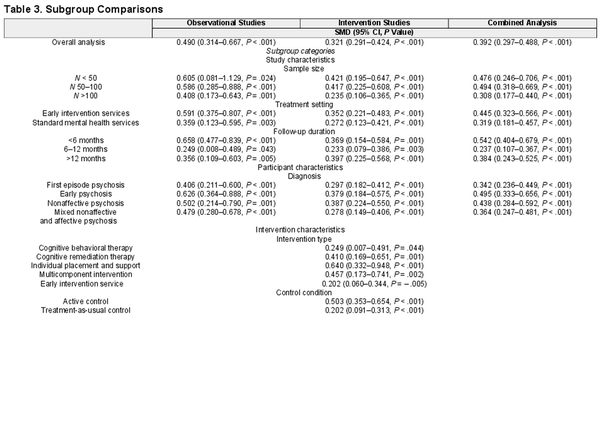

Further Subgroup Comparisons and Meta-regression Analyses

We carried out subgroup comparisons to consider the effects of potential confounding variables on the effect sizes calculated, including study characteristics (length of follow-up, sample size, treatment setting), participant characteristics (diagnosis: FEP vs early psychosis, and nonaffective psychosis vs mixed diagnosis), intervention type and control condition (for intervention studies only). Subgroup comparisons were carried out separately for observational studies and for interventional studies, and also for all studies combined (see table 3).

Following subgroup comparisons, we carried out meta-regression analyses separately for observational studies and for intervention studies, and also for all studies combined. Here, confounding variables were entered in a meta-regression as covariates to control for the potential influences on the effect of measure type (categorized as GAF, global measures, social measures, and NEET status) on effect sizes. In the CMA program, it is possible to evaluate the effect of 1 variable (in this case type of functioning measure) on effect sizes, while holding other possible confounding variables constant. Separate meta-regressions were carried out for observational studies and for intervention studies, and also for all studies combined. For observational studies, when covariates were controlled for, measure type significantly predicted differences in effect sizes (Q = 23.43, df = 3, P < .001, r2 = 0.13), suggesting that observed differences between measures were not explained by individual differences. For the group of intervention studies, when covariates were controlled for, measure type significantly predicted differences in effect sizes (Q = 10.91, df = 3, P = .012, r2 = 0.19).

Discussion

Summary of Findings

This study provided a systematic review and meta-analysis of measures of functioning most widely employed in early psychosis research. The aim of the review was to (1) gather information about the measures most frequently used in the literature, and (2) quantitatively assess available measures in terms of the effect sizes for differences or changes in function. The limited consensus on measurement approach is reflected in the wide variation of published measures, with 36 different measures identified in our search.

Ten measures were identified as most commonly used (included in 5 or more publications), 7 of which represented global measures of function. Measures varied in terms of aspects of functioning assessed, and the level of detail assessed. For the most common measures identified, psychometric properties appear to be comparable (except for reliability and validity issues with the GAF, see supplementary section S1). Our analyses suggested that the GAF and other global scales demonstrated smaller effect sizes for differences in functioning (over time and in response to treatment) than more specific measures of social functioning, and NEET status. These findings remained significant even after variability in study and participant characteristics were accounted for. Given the relative ease with which both social functioning measures and NEET status can be administered and scored, preference should be given to using these measures over more global estimates such as the GAF and SOFAS. NEET status differs significantly from other measures in that it is a more objective measure, but is also purely categorical and does not provide any qualitative information in terms of employment or education. Despite this, our findings highlight the potential usefulness of NEET status as an indication of functioning in terms of changes in effect sizes. Our findings also highlight the issues of combining different aspects of functioning into a single global score, suggesting that specific subscales are capturing different elements of social and occupational functioning and should be considered separately.

Issues With Global Measures of Social and Occupational Function

The most widely used measure of function in early psychosis is the GAF, a clinician rated impressionistic global score of social and occupational function and symptom severity. The GAF was initially introduced as a measure of global severity of illness as part of the DSM-III-R to meet the requirement for an easy and quick measure. A key criticism of the GAF is that the 1-dimensional score it provides poorly describes the complex picture of functioning in the context of mental ill-health. The GAF was updated in the DSM-IV to exclude the ratings of symptom severity in the overall score, and the SOFAS was included in the updated version. While the simplicity of the GAF and SOFAS have led to their widespread use (the GAF used almost twice as often as the SOFAS, and the SOFAS used twice as often as the next most frequently used global measure), a single rating of overall symptom, social and occupational function has been criticized as making interpretation of specific aspects of functioning difficult. This is important because individuals with lived experience of psychosis consistently highlight social and occupational function as the most important aspects of their recovery and a treatment priority for them. It is also important because social and occupational recovery may be independent of changes in psychotic symptoms, and independent of each other. The present study again highlights the limitations of the GAF by indicating that it is among the least sensitive measures of function when measured in terms of effect size for case-control between-group differences, longitudinal differences, or treatment response.

The Value of More Specific Assessment of Social and Occupational Function

By comparison to global measures such as the GAF and SOFAS, our meta-analysis of NEET status—an indication of occupational function based simply on an individuals status as currently in education, training, or employment, was observed as significantly more effective in detecting changes in function over time. A return to education, training, or employment has the ecological validity of frequently representing a valued goal for recovery among patients. For researchers and clinicians, it has the additional benefit of being extremely quick and easy to measure reliably.

Several measures that assess specific aspects of social function showed the largest effect sizes in terms of changes in function over time and in response to intervention in early psychosis. Among these, the Global Functioning Scale: social scale includes an evaluation of both the quantity and quality of peer relationships, level of peer conflict, age-appropriate intimate relationships, and involvement with family members. Similarly, the Role Functioning Scale: social scale assesses number of close friends, frequency of contact, and quality of engagement in interactions. The MIRECC GAF: social scale is a score of overall social function on a scale of 0–100 with different anchor points. Despite the differing levels of detail ascertained, these types of measures appeared to be able to detect changes over time and can be completed in a matter of minutes.

These observations highlight the value of considering individual elements of social and occupation function separately to get a better understanding of changes in function over time. Important differences may emerge in early psychosis with different aspects of function, and using a measure that does not differentiate between these aspects of functioning could mask potential changes over time.

Limitations and Future Directions

A limitation of this review was the limited number of studies available for inclusion in our meta-analyses. In addition, significant heterogeneity was noted across studies, likely reflecting variability in terms of sample size, length of follow-up, and outcome measures. We conducted subgroup and meta-regression analyses to account for this variability and to evaluate the effect the type of functioning measure has on effect sizes when controlling for possible confounding variables. A significant percentage of studies did not provide adequate information to allow inclusion in meta-analysis. In most cases, this was due to the inclusion of the functioning measure as a secondary outcome that was not the focus of the analysis, and therefore studies did not report relevant scores and statistics required for our meta-analysis, reflecting a previous lack of focus on social and occupational focus in the literature. There was also an absence of an adequate assessment of the psychometric properties of existing measures, with scarce data available on their validity, reliability, responsiveness, and sensitivity in early psychosis. This meant we were unable to compare different measures based on validity and reliability statistics. In addition, data were collected on outpatients rather than inpatients. There was a wide variation in definitions of FEP. Definitions varied in terms of whether they were based on first treatment contact, duration of antipsychotic medication use, or duration of psychosis. This is further complicated by issues regarding disparities in illness identification as a function of racialized identity and access to care. Significant publication bias was noted for intervention studies likely due to the issue of reporting bias for nonsignificant findings in the literature for interventions. Our search was limited to articles published up to March 2021, as a result we may have missed more recent findings published in the last 2 years. However, given the large amount of data considered from studies conducted over a 21-year timeframe, we believe our findings sufficiently represent the existing literature and address an important issue in this field of research.

While we were able to compare different types of measures (GAF vs global measures vs social measures), further analysis is needed to understand more about how individual measures differ from one another in terms of ability to detect change in function. Some measures that include multiple subscales with a large number of items may not be necessary, and information about what aspects of function are most responsive to change could be used to improve and refine existing measures. We were unable to compare self-report vs interview-rated scales, and it would be useful to understand differences in effect sizes for change in function based on how measures are administered. In addition, future studies could control for length and severity of illness, as these factors could potentially influence functioning. Given the complexity of symptoms experienced by people with psychosis, when measuring social function it will be important to consider how the positive, negative, and cognitive symptoms of psychosis impact different aspects of functioning. Further assessment of the validity, reliability, and sensitivity of existing measures for use with people with early psychosis is necessary.

Conclusions

These findings highlight some of the difficulties in measuring social and occupational function in early psychosis. They suggest that more specific measures of social function (as opposed to impressionistic global measures) are better able to detect changes in function over time and in response to treatment. Measures that include more specific subscales such as the Global Functioning Scale: social scale, the Role Functioning Scale: social scale, the MIRECC GAF: social scale, should, along with NEET status be considered for inclusion in studies aiming to detect functional changes. Given the significant social and economic costs associated with psychosis, and the importance of social and occupational function as recovery goals for patients, further development of functioning measurement remains a priority for our field.

Acknowledgments

The authors have declared that there are no conflicts of interest in relation to the subject of this study.

References

- 1. World Health Organization. Depression and Other Common Mental Disorders: Global Health Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- 2. Behan C, Kennelly B, O’Callaghan E. The economic cost of schizophrenia in Ireland: a cost of illness study. Ir J Psychol Med.2008;25(3):80–87.

- 3. Ekman M, Granstrom O, Omerov S, Jacob J, Landen M. The societal cost of schizophrenia in Sweden. J Ment Health Policy Econ.2013;16(1):13–25.

- 4. Evensen S, Wisløff T, Lystad JU, Bull H, Ueland T, Falkum E. Prevalence, employment rate, and cost of schizophrenia in a high-income welfare society: a population-based study using comprehensive health and welfare registers. Schizophr Bull.2016;42(2):476–483.

- 5. Phanthunane P, Vos T, Whiteford H, Bertram M. Improving mental health policy in the case of schizophrenia in Thailand: evidence-based information for efficient solutions. BMC Public Health.2012;12:1–32.

- 6. Frawley E, Cowman M, Lepage M, Donohoe G. Social and occupational recovery in early psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of psychosocial interventions. Psychol Med.2021;53(5):1787–1798.

- 7. Andreasen NC. Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS). Iowa: University of Iowa; 2000.

- 8. Andreasen NC. The Scale for the Assessment of Negative Symptoms (SANS): conceptual and theoretical foundations. Br J Psychiatry.1989;155(7):49–52.

- 9. Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull.1987;13(2):261–276.

- 10. Burns T, Patrick D. Social functioning as an outcome measure in schizophrenia studies. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2007;116(6):403–418.

- 11. Piersma HL, Boes JL. The GAF and psychiatric outcome: a descriptive report. Community Ment Health J.1997;33(1):35–41.

- 12. Hilsenroth MJ, Ackerman SJ, Blagys MD, et al Reliability and validity of DSM-IV axis V. Am J Psychiatry.2000;157(11):1858–1863.

- 13. Robertson DA, Hargreaves A, Kelleher EB, et al Social dysfunction in schizophrenia: an investigation of the GAF scale’s sensitivity to deficits in social cognition. Schizophr Res.2013;146(1–3):363–365.

- 14. Aas IM. Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF): properties and frontier of current knowledge. Ann Gen Psychiatry.2010;9:20–21.

- 15. Niv N, Cohen AN, Sullivan G, Young AS. The MIRECC version of the global assessment of functioning scale: reliability and validity. Psychiatr Serv.2007;58(4):529–535.

- 16. Cowman M, Holleran L, Lonergan E, O’Connor K, Birchwood M, Donohoe G. Cognitive predictors of social and occupational functioning in early psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cross-sectional and longitudinal data. Schizophr Bull.2021;47(5):1243–1253.

- 17. Rokita KI, Dauvermann MR, Donohoe G. Early life experiences and social cognition in major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Eur Psychiatry.2018;53:123–133.

- 18. Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive Meta-analysis Version 3. Englewood, NJ: Biostat; 2013.

- 19. Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JP, Rothstein HR. Introduction to Meta-analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2011.

- 20. Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in metaanalysis. Biometrics.2000;56(2):455–463.

- 21. Egger M, Smith GD, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ.1997;315(7109):629–634.

- 22. Addington J, Young J, Addington D. Social outcome in early psychosis. Psychol Med.2003;33(6):1119–1124.

- 23. Addington J, Saeedi H, Addington D. The course of cognitive functioning in first episode psychosis: changes over time and impact on outcome. Schizophr Res.2005;78(1):35–43.

- 24. Addington J, Saeedi H, Addington D. Influence of social perception and social knowledge on cognitive and social functioning in early psychosis. Br J Psychiatry.2006;189(4):373–378.

- 25. Addington J, Addington D. Social and cognitive functioning in psychosis. Schizophr Res.2008;99(1–3):176–181.

- 26. Albert N, Bertelsen M, Thorup A, et al Predictors of recovery from psychosis: analyses of clinical and social factors associated with recovery among patients with first-episode psychosis after 5 years. Schizophr Res.2011;125(2–3):257–266.

- 27. Allott K, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Killackey EJ, Bendall S, McGorry PD, Jackson HJ. Patient predictors of symptom and functional outcome following cognitive behaviour therapy or befriending in first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res.2011;132(2–3):125–130.

- 28. Alvarez-Jimenez M, Gleeson JF, Henry LP, et al Road to full recovery: longitudinal relationship between symptomatic remission and psychosocial recovery in first-episode psychosis over 7.5 years. Psychol Med.2012;42(3):595–606.

- 29. Amminger GP, Henry LP, Harrigan SM, et al Outcome in early-onset schizophrenia revisited: findings from the early psychosis prevention and intervention centre long-term follow-up study. Schizophr Res.2011;131(1–3):112–119.

- 30. Amoretti S, Mezquida G, Rosa AR, et al; PEPs Group. The functioning assessment short test (FAST) applied to first-episode psychosis: psychometric properties and severity thresholds. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol.2021;47:98–111.

- 31. Baksheev GN, Allott K, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Killackey E. Predictors of vocational recovery among young people with first-episode psychosis: findings from a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Rehabil J.2012;35(6):421–427.

- 32. Bjornestad J, ten Velden Hegelstad W, Joa I, et al “With a little help from my friends” social predictors of clinical recovery in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res.2017;255:209–214.

- 33. Boschi S, Adams RE, Bromet EJ, Lavelle JE, Everett E, Galambos N. Coping with psychotic symptoms in the early phases of schizophrenia. Am J Orthopsychiatry.2000;70(2):242–252.

- 34. Bourdeau G, Lecomte T, Lysaker PH. Stages of recovery in early psychosis: associations with symptoms, function, and narrative development. Psychol Psychother.2015;88(2):127–142.

- 35. Bratlien U, Øie M, Lien L, et al Social dysfunction in first-episode psychosis and relations to neurocognition, duration of untreated psychosis and clinical symptoms. Psychiatry Res.2013;207(1–2):33–39.

- 36. Breitborde NJ, Kleinlein P, Srihari VH. Self-determination and first-episode psychosis: associations with symptomatology, social and vocational functioning, and quality of life. Schizophr Res.2012;137(1–3):132–136.

- 37. Breitborde NJ, Bell EK, Dawley D, et al The Early Psychosis Intervention Center (EPICENTER): development and six-month outcomes of an American first-episode psychosis clinical service. BMC Psychiatry.2015;15(1):266–277.

- 38. Cacciotti-Saija C, Langdon R, Ward PB, Hickie IB, Guastella AJ. Clinical symptoms predict concurrent social and global functioning in an early psychosis sample. Early Interv Psychiatry.2018;12(2):177–184.

- 39. Cassidy CM, Norman R, Manchanda R, Schmitz N, Malla A. Testing definitions of symptom remission in first-episode psychosis for prediction of functional outcome at 2 years. Schizophr Bull.2010;36(5):1001–1008.

- 40. Catalan A, Angosto V, Díaz A, et al The relationship between theory of mind deficits and neurocognition in first episode-psychosis. Psychiatry Res.2018;268:361–367.

- 41. Chang WC, Chan GH, Jim OT, et al Optimal duration of an early intervention programme for first-episode psychosis: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry.2015;206:492–500.

- 42. Chang WC, Chu AO, Kwong VW, et al Patterns and predictors of trajectories for social and occupational functioning in patients presenting with first-episode non-affective psychosis: a three-year follow-up study. Schizophr Res.2018;197:131–137.

- 43. Chang WC, Chu AO, Treadway MT, et al Effort-based decision-making impairment in patients with clinically-stabilized first-episode psychosis and its relationship with amotivation and psychosocial functioning. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol.2019;29(5):629–642.

- 44. Clausen L, Hjorthøj CR, Thorup A, et al Change in cannabis use, clinical symptoms and social functioning among patients with first-episode psychosis: a 5-year follow-up study of patients in the OPUS trial. Psychol Med.2014;44(1):117–126.

- 45. Conus P, Cotton S, Schimmelmann BG, McGorry PD, Lambert M. The first-episode psychosis outcome study: premorbid and baseline characteristics of an epidemiological cohort of 661 first-episode psychosis patients. Early Interv Psychiatry.2007;1(2):191–200.

- 46. Cotton SM, Lambert M, Schimmelmann BG, et al Gender differences in premorbid, entry, treatment, and outcome characteristics in a treated epidemiological sample of 661 patients with first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res.2009;114(1–3):17–24.

- 47. Cotton SM, Lambert M, Schimmelmann BG, et al Predictors of functional status at service entry and discharge among young people with first episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.2017;52(5):575–585.

- 48. Cotton SM, Filia KM, Lambert M, et al Not in education, employment and training status in the early stages of bipolar I disorder with psychotic features. Early Interv Psychiatry.2022;16(6):609–617.

- 49. Cruz LN, Kline E, Seidman LJ, et al Longitudinal determinants of client treatment satisfaction in an intensive first-episode psychosis treatment programme. Early Interv Psychiatry.2017;11(4):354–362.

- 50. Davies G, Fowler D, Greenwood K. Metacognition as a mediating variable between neurocognition and functional outcome in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull.2017;43(4):824–832.

- 51. Dickerson FB, Stallings C, Origoni A, Boronow JJ, Sullens A, Yolken R. Predictors of occupational status six months after hospitalization in persons with a recent onset of psychosis. Psychiatry Res.2008;160(3):278–284.

- 52. Drake RE, Xie H, Bond GR, McHugo GJ, Caton CL. Early psychosis and employment. Schizophr Res.2013;146(1–3):111–117.

- 53. Dudley R, Nicholson M, Stott P, Spoors G. Improving vocational outcomes of service users in an Early Intervention in Psychosis service. Early Interv Psychiatry.2014;8(1):98–102.

- 54. Eack SM, Greenwald DP, Hogarty SS, et al Cognitive enhancement therapy for early-course schizophrenia: effects of a two-year randomized controlled trial. Psychiatr Serv.2009;60(11):1468–1476.

- 55. Evensen J, Røssberg JI, Barder H, et al Flat affect and social functioning: a 10 year follow-up study of first episode psychosis patients. Schizophr Res.2012;139(1–3):99–104.

- 56. Faerden A, Friis S, Agartz I, et al Apathy and functioning in first-episode psychosis. Psychiatr Serv.2009;60(11):1495–1503.

- 57. Fervaha G, Foussias G, Agid O, Remington G. Motivational deficits in early schizophrenia: prevalent, persistent, and key determinants of functional outcome. Schizophr Res.2015;166(1–3):9–16.

- 58. Fournier M, Scolamiero M, Gholam-Rezaee MM, et al Topology predicts long-term functional outcome in early psychosis. Mol Psychiatry.2021;26(9):5335–5346.

- 59. Fowler D, Hodgekins J, Painter M, et al Cognitive behaviour therapy for improving social recovery in psychosis: a report from the ISREP MRC Trial Platform study (Improving Social Recovery in Early Psychosis). Psychol Med.2009;39(10):1627–1636.

- 60. Fowler D, Hodgekins J, French P, et al Social recovery therapy in combination with early intervention services for enhancement of social recovery in patients with first-episode psychosis (SUPEREDEN3): a single-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry.2018;5(1):41–50.

- 61. Fulford D, Niendam TA, Floyd EG, et al Symptom dimensions and functional impairment in early psychosis: more to the story than just negative symptoms. Schizophr Res.2013;147(1):125–131.

- 62. Fulford D, Piskulic D, Addington J, Kane JM, Schooler NR, Mueser KT. Prospective relationships between motivation and functioning in recovery after a first episode of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull.2018;44(2):369–377.

- 63. Fulford D, Meyer-Kalos PS, Mueser KT. Focusing on recovery goals improves motivation in first-episode psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.2020;55(12):1629–1637.

- 64. Gardner A, Cotton SM, Allott K, Filia KM, Hester R, Killackey E. Social inclusion and its interrelationships with social cognition and social functioning in first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry.2019;13(3):477–487.

- 65. Garety PA, Craig TK, Dunn G, et al Specialised care for early psychosis: symptoms, social functioning and patient satisfaction: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry.2006;188(1):37–45.

- 66. Golay P, Ramain J, Jenni R, et al Six months functional response to early psychosis intervention program best predicts outcome after three years. Schizophr Res.2021;238:62–69.

- 67. Gonzalez-Blanch C, Gleeson JF, Koval P, Cotton SM, McGorry PD, Alvarez-Jimenez M. Social functioning trajectories of young first-episode psychosis patients with and without cannabis misuse: a 30-month follow-up study. PLoS One.2015;10(4):e0122404.

- 68. González-Ortega I, Rosa A, Alberich S, et al Validation and use of the functioning assessment short test in first psychotic episodes. J Nerv Ment Dis.2010;198(11):836–840.

- 69. González-Ortega I, de Los Mozos V, Echeburúa E, et al Working memory as a predictor of negative symptoms and functional outcome in first episode psychosis. Psychiatry Res.2013;206(1):8–16.

- 70. González-Ortega I, Vega P, Echeburúa E, et al A multicentre, randomised, controlled trial of a combined clinical treatment for first-episode psychosis. Int J Environ Res Public Health.2021;18(14):7239–7252.

- 71. Goulding SM, Franz L, Bergner E, Compton MT. Social functioning in urban, predominantly African American, socially disadvantaged patients with first-episode nonaffective psychosis. Schizophr Res.2010;119(1–3):95–100.

- 72. Grant C, Addington J, Addington D, Konnert C. Social functioning in first-and multiepisode schizophrenia. Can J Psychiatry.2001;46(8):746–749.

- 73. Griffiths SL, Birchwood M, Khan A, Wood SJ. Predictors of social and role outcomes in first episode psychosis: a prospective 12-month study of social cognition, neurocognition and symptoms. Early Interv Psychiatry.2021;15(4):993–1001.

- 74. Hall MH, Holton KM, Öngür D, Montrose D, Keshavan MS. Longitudinal trajectory of early functional recovery in patients with first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res.2019;209:234–244.

- 75. Harder S, Koester A, Valbak K, Rosenbaum B. Five-year follow-up of supportive psychodynamic psychotherapy in first-episode psychosis: long-term outcome in social functioning. Psychiatry.2014;77(2):155–168.

- 76. Haug E, Øie M, Andreassen OA, et al Anomalous self-experiences contribute independently to social dysfunction in the early phases of schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder. Compr Psychiatry.2014;55(3):475–482.

- 77. Hegelstad WT, Bronnick KS, Barder HE, et al Preventing poor vocational functioning in psychosis through early intervention. Psychiatr Serv.2017;68(1):100–103.

- 78. Henry LP, Amminger GP, Harris MG, et al The EPPIC follow-up study of first-episode psychosis: longer-term clinical and functional outcome 7 years after index admission. J Clin Psychiatry.2010;71(6):716–728.

- 79. Hodgekins J, Birchwood M, Christopher R, et al Investigating trajectories of social recovery in individuals with first-episode psychosis: a latent class growth analysis. Br J Psychiatry.2015;207(6):536–543.

- 80. Hodgekins J, French P, Birchwood M, et al Comparing time use in individuals at different stages of psychosis and a non-clinical comparison group. Schizophr Res.2015;161(2–3):188–193.

- 81. Horan WP, Green MF, DeGroot M, et al Social cognition in schizophrenia, part 2: 12-month stability and prediction of functional outcome in first-episode patients. Schizophr Bull.2012;38(4):865–872.

- 82. Hui CL, Ko WT, Chang WC, Lee EH, Chan SK, Chen EY. Clinical and functional correlates of financially deprived women with first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry.2019;13(3):639–645.

- 83. Iyer S, Mustafa S, Gariépy G, et al A NEET distinction: youths not in employment, education or training follow different pathways to illness and care in psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.2018;53(12):1401–1411.

- 84. Jackson HJ, McGorry PD, Killackey E, et al Acute-phase and 1-year follow-up results of a randomized controlled trial of CBT versus Befriending for first-episode psychosis: the ACE project. Psychol Med.2008;38(5):725–735.

- 85. Jaracz K, Górna K, Rybakowski F. Social functioning in first-episode schizophrenia. A prospective follow-up study. Arch Psychiatry Psychother.2007;4:19–27.

- 86. Kam SM, Singh SP, Upthegrove R. What needs to follow early intervention? Predictors of relapse and functional recovery following first-episode psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry.2015;9(4):279–283.

- 87. Killackey E, Jackson HJ, McGorry PD. Vocational intervention in first-episode psychosis: individual placement and support v. treatment as usual. Br J Psychiatry.2008;193(2):114–120.

- 88. Killackey E, Allott K, Jackson HJ, et al Individual placement and support for vocational recovery in first-episode psychosis: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry.2019;214(2):76–82.

- 89. Klaas HS, Clémence A, Marion-Veyron R, et al Insight as a social identity process in the evolution of psychosocial functioning in the early phase of psychosis. Psychol Med.2017;47(4):718–729.

- 90. Kuipers E, Holloway F, Rabe-Hesketh S, Tennakoon L; Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST). An RCT of early intervention in psychosis: Croydon Outreach and Assertive Support Team (COAST). Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.2004;39(5):358–363.

- 91. Kuzman MR, Makaric P, Kuharic DB, et al General functioning in patients with first-episode psychosis after the first 18 months of treatment. J Clin Psychopharmacol.2020;40(4):366–372.

- 92. Lee RS, Redoblado-Hodge MA, Naismith SL, Hermens DF, Porter MA, Hickie IB. Cognitive remediation improves memory and psychosocial functioning in first-episode psychiatric out-patients. Psychol Med.2013;43(6):1161–1173.

- 93. Leeson VC, Barnes TR, Hutton SB, Ron MA, Joyce EM. IQ as a predictor of functional outcome in schizophrenia: a longitudinal, four-year study of first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Res.2009;107(1):55–60.

- 94. Leighton SP, Upthegrove R, Krishnadas R, et al Development and validation of multivariable prediction models of remission, recovery, and quality of life outcomes in people with first episode psychosis: a machine learning approach. Lancet Digit Health.2019;1(6):e261–e270.

- 95. Macneil CA, Hasty M, Cotton S, et al Can a targeted psychological intervention be effective for young people following a first manic episode? Results from an 18-month pilot study. Early Interv Psychiatry.2012;6(4):380–388.

- 96. Maraj A, Mustafa S, Joober R, Malla A, Shah JL, Iyer SN. Caught in the “NEET Trap”: the intersection between vocational inactivity and disengagement from an early intervention service for psychosis. Psychiatr Serv.2019;70(4):302–308.

- 97. Mendella PD, Burton CZ, Tasca GA, Roy P, Louis LS, Twamley EW. Compensatory cognitive training for people with first-episode schizophrenia: results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res.2015;162(1–3):108–111.

- 98. Menezes NM, Malla AM, Norman RM, Archie S, Roy P, Zipursky RB. A multi-site Canadian perspective: examining the functional outcome from first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2009;120(2):138–146.

- 99. Meng H, Schimmelmann BG, Mohler B, et al Pretreatment social functioning predicts 1-year outcome in early onset psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2006;114(4):249–256.

- 100. Minor KS, Friedman-Yakoobian M, Leung YJ, et al The impact of premorbid adjustment, neurocognition, and depression on social and role functioning in patients in an early psychosis treatment program. Aust N Z J Psychiatry.2015;49(5):444–452.

- 101. Murphy TK, Haigh SM, Coffman BA, Salisbury DF. Mismatch negativity and impaired social functioning in long-term and in first episode schizophrenia spectrum psychosis. Front Psychiatry.2020;11:544–545.

- 102. Mustafa SS, Malla A, Joober R, et al Unfinished business: functional outcomes in a randomized controlled trial of a three-year extension of early intervention versus regular care following two years of early intervention for psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2022;145(1):86–99.

- 103. Norman RM, Mallal AK, Manchanda R, et al Does treatment delay predict occupational functioning in first-episode psychosis? Schizophr Res.2007;91(1–3):259–262.

- 104. Norman RM, Manchanda R, Malla AK, Windell D, Harricharan R, Northcott S. Symptom and functional outcomes for a 5 year early intervention program for psychoses. Schizophr Res.2011;129(2–3):111–115.

- 105. Nossel I, Wall MM, Scodes J, et al Results of a coordinated specialty care program for early psychosis and predictors of outcomes. Psychiatr Serv.2018;69(8):863–870.

- 106. Nuechterlein KH, Subotnik KL, Ventura J, et al Enhancing return to work or school after a first episode of schizophrenia: the UCLA RCT of Individual Placement and Support and Workplace Fundamentals Module training. Psychol Med.2020;50(1):20–28.

- 107. Østergaard Christensen T, Vesterager L, Krarup G, et al Cognitive remediation combined with an early intervention service in first episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2014;130(4):300–310.

- 108. Pencer A, Addington J, Addington D. Outcome of a first episode of psychosis in adolescence: a 2-year follow-up. Psychiatry Res.2005;133(1):35–43.

- 109. Penn DL, Uzenoff SR, Perkins D, et al A pilot investigation of the Graduated Recovery Intervention Program (GRIP) for first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res.2011;125(2–3):247–256.

- 110. Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, et al A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. BMJ.2005;331:602–609.

- 111. Renwick L, Drennan J, Sheridan A, et al Subjective and objective quality of life at first presentation with psychosis. Early Interv Psychiatry.2017;11(5):401–410.

- 112. Rosenheck R, Mueser KT, Sint K, et al Supported employment and education in comprehensive, integrated care for first episode psychosis: effects on work, school, and disability income. Schizophr Res.2017;182:120–128.

- 113. Ruggeri M, Bonetto C, Lasalvia A, et al Feasibility and effectiveness of a multi-element psychosocial intervention for first-episode psychosis: results from the cluster-randomized controlled GET UP PIANO trial in a catchment area of 10 million inhabitants. Schizophr Bull.2015;41(5):1192–1203.

- 114. Schlosser DA, Campellone TR, Truong B, et al Efficacy of PRIME, a mobile app intervention designed to improve motivation in young people with schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull.2018;44(5):1010–1020.

- 115. Simonsen E, Friis S, Haahr U, et al Clinical epidemiologic first-episode psychosis: 1-year outcome and predictors. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2007;116(1):54–61.

- 116. Singh F, Pineda J, Cadenhead KS. Association of impaired EEG mu wave suppression, negative symptoms and social functioning in biological motion processing in first episode of psychosis. Schizophr Res.2011;130(1–3):182–186.

- 117. Stain HJ, Hodne S, Joa I, et al The relationship of verbal learning and verbal fluency with written story production: implications for social functioning in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res.2012;138(2–3):212–217.

- 118. Stain HJ, Brønnick K, Hegelstad WT, et al Impact of interpersonal trauma on the social functioning of adults with first-episode psychosis. Schizophr Bull.2014;40(6):1491–1498.

- 119. Sullivan S, Lewis G, Mohr C, et al The longitudinal association between social functioning and theory of mind in first-episode psychosis. Cogn Neuropsychol.2014;19(1):58–80.

- 120. Tandberg M, Ueland T, Sundet K, et al Neurocognition and occupational functioning in patients with first-episode psychosis: a 2-year follow-up study. Psychiatry Res.2011;188(3):334–342.

- 121. Tandberg M, Ueland T, Andreassen OA, Sundet K, Melle I. Factors associated with occupational and academic status in patients with first-episode psychosis with a particular focus on neurocognition. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.2012;47(11):1763–1773.

- 122. Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM Jr, et al Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry.2000;157(2):220–228.

- 123. Tohen M, Strakowski SM, Zarate C Jr, et al The McLean–Harvard first-episode project: 6-month symptomatic and functional outcome in affective and nonaffective psychosis. Biol Psychiatry.2000;48(6):467–476.

- 124. Trauelsen AM, Bendall S, Jansen JE, et al Childhood adversities: social support, premorbid functioning and social outcome in first-episode psychosis and a matched case-control group. Aust N Z J Psychiatry.2016;50(8):770–782.

- 125. Uren J, Cotton SM, Killackey E, Saling MM, Allott K. Cognitive clusters in first-episode psychosis: overlap with healthy controls and relationship to concurrent and prospective symptoms and functioning. Neuropsychology.2017;31(7):787–797.

- 126. van der Ven E, Scodes J, Basaraba C, et al Trajectories of occupational and social functioning in people with recent-onset non-affective psychosis enrolled in specialized early intervention services across New York state. Schizophr Res.2020;222:218–226.

- 127. Ventura J, Subotnik KL, Gretchen-Doorly D, et al Cognitive remediation can improve negative symptoms and social functioning in first-episode schizophrenia: a randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res.2019;203:24–31.

- 128. Ventura J, Welikson T, Ered A, et al Virtual reality assessment of functional capacity in the early course of schizophrenia: associations with cognitive performance and daily functioning. Early Interv Psychiatry.2020;14(1):106–114.

- 129. Verdolini N, Amoretti S, Mezquida G, et al The effect of family environment and psychiatric family history on psychosocial functioning in first-episode psychosis at baseline and after 2 years. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol.2021;49:54–68.

- 130. Verma S, Subramaniam M, Abdin E, Poon LY, Chong SA. Symptomatic and functional remission in patients with first-episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2012;126(4):282–289.

- 131. Vidarsdottir OG, Roberts DL, Twamley EW, Gudmundsdottir B, Sigurdsson E, Magnusdottir BB. Integrative cognitive remediation for early psychosis: results from a randomized controlled trial. Psychiatry Res.2019;273:690–698.

- 132. Voges M, Addington J. The association between social anxiety and social functioning in first episode psychosis. Schizophr Res.2005;76(2–3):287–292.

- 133. White C, Stirling J, Hopkins R, et al Predictors of 10-year outcome of first-episode psychosis. Psychol Med.2009;39(9):1447–1456.

- 134. Whitehorn D, Brown J, Richard J, Rui Q, Kopala L. Multiple dimensions of recovery in early psychosis. Int Rev Psychiatry.2002;14(4):273–283.

- 135. Williams LM, Whitford TJ, Flynn G, et al General and social cognition in first episode schizophrenia: identification of separable factors and prediction of functional outcome using the IntegNeuro test battery. Schizophr Res.2008;99(1–3):182–191.

- 136. Wright AC, Davies G, Fowler D, Greenwood KE. Self-defining memories predict engagement in structured activity in first episode psychosis, independent of neurocognition and metacognition. Schizophr Bull.2019;45(5):1081–1091.

- 137. Wykes T, Newton E, Landau S, Rice C, Thompson N, Frangou S. Cognitive remediation therapy (CRT) for young early onset patients with schizophrenia: an exploratory randomized controlled trial. Schizophr Res.2007;94(1–3):221–230.

- 138. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

- 139. Goldman HH, Skodol AE, Lave TR. Revising axis V for DSM-IV: a review of measures of social functioning. Am J Psychiatry.1992;149(9):1148–1156.

- 140. Heinrichs DW, Hanlon TE, Carpenter WT Jr. The quality of life scale: an instrument for rating the schizophrenic deficit syndrome. Schizophr Bull.1984;10(3):388–398.

- 141. Birchwood M, Smith JO, Cochrane R, Wetton S, Copestake SO. The social functioning scale the development and validation of a new scale of social adjustment for use in family intervention programmes with schizophrenic patients. Br J Psychiatry.1990;157(6):853–859.

- 142. Strauss JS, Carpenter WT Jr. The prediction of outcome in schizophrenia. I. Characteristics of outcome. Arch Gen Psychiatry.1972;27(6):739–746.

- 143. Cornblatt BA, Auther AM, Niendam T, et al Preliminary findings for two new measures of social and role functioning in the prodromal phase of schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull.2007;33(3):688–702.

- 144. Goodman SH, Sewell DR, Cooley EL, Leavitt N. Assessing levels of adaptive functioning: the Role Functioning Scale. Community Ment Health J.1993;29(2):119–131.

- 145. Rosa AR, Sánchez-Moreno J, Martínez-Aran A, et al Validity and reliability of the Functioning Assessment Short Test (FAST) in bipolar disorder. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health.2007;3(1):51–58.

- 146. Lehman AF. The well-being of chronic mental patients: assessing their quality of life. Arch Gen Psychiatry.1983;40(4):369–373.

- 147. World Health Organization. The Life Chart Schedule. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1992.

- 148. Patterson TL, Goldman S, McKibbin CL, Hughs T, Jeste DV. UCSD Performance-Based Skills Assessment: development of a new measure of everyday functioning for severely mentally ill adults. Schizophr Bull.2001;27(2):235–245.

- 149. Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale: a procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry.1976;33(6):766–771.

- 150. Farkas MD, Rogers ES, Thurer S. Rehabilitation outcome of long-term hospital patients left behind by deinstitutionalization. Psychiatr Serv.1987;38(8):864–870.

- 151. Morosini PL, Magliano L, Brambilla LA, Ugolini S, Pioli R. Development, reliability and acceptability of a new version of the DSM-IV Social and Occupational Functioning Assessment Scale (SOFAS) to assess routine social functioning. Acta Psychiatr Scand.2000;101(4):323–329.

- 152. Weissman MM, Bothwell S. Assessment of social adjustment by patient self-report. Arch Gen Psychiatry.1976;33(9):1111–1115.

- 153. World Health Organization. WHO Psychiatric Disability Assessment Schedule. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1988.

- 154. Wiersma D, DeJong A, Ormel J. The Groningen Social Disabilities Schedule: development, relationship with ICIDH, and psychometric properties. Int J Rehabil Res.1988;11(3):213–224.

- 155. Rosen A, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, Parker G. The life skills profile: a measure assessing function and disability in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull.1989;15(2):325–337.

- 156. Patterson TL, Moscona S, McKibbin CL, Davidson K, Jeste DV. Social skills performance assessment among older patients with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res.2001;48(2–3):351–360.

- 157. Donahoe CP, Carter MJ, Bloem WD, Hirsch GL, Laasi N, Wallace CJ. Assessment of interpersonal problem-solving skills. Psychiatry.1990;53(4):329–339.

- 158. Wallace CJ, Lecomte T, Wilde J, Liberman RP. CASIG: a consumer-centered assessment for planning individualized treatment and evaluating program outcomes. Schizophr Res.2001;50(1–2):105–119.

- 159. Becker M, Diamond R, Sainfort F. A new patient focused index for measuring quality of life in persons with severe and persistent mental illness. Qual Life Res.1993;2(4):239–251.

- 160. Lecomte T, Corbière M, Ehmann T, Addington J, Abdel-Baki A, MacEwan B. Development and preliminary validation of the first episode social functioning scale for early psychosis. Psychiatry Res.2014;216(3):412–417.

- 161. Wing J, Beevor AS, Curtis RH. Health of the nation outcome scales (HoNOS): research and development. Br J Psychiatry.1998;172:11–18.

- 162. Kielhofner G, Forsyth K, Kramer J, Iyenger A. Developing the occupational self assessment: the use of Rasch analysis to assure internal validity, sensitivity and reliability. Br J Occup Ther. 2009;72(3):94–104.

- 163. Sheehan DV. The Anxiety Disease. New York, NY: Scribner; 1983.

- 164. Bosc M, Dubini A, Polin V. Development and validation of a social functioning scale, the Social Adaptation Self-evaluation Scale. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol.1997;7:S57–S70; discussion S71.

- 165. Roth RM, Gioia GA, Isquith PK. BRIEF-A: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function—Adult Version. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2005.

- 166. Goldstein MJ. Further data concerning the relation between premorbid adjustment and paranoid symptomatology. Schizophr Bull.1978;4(2):236–243.

- 167. Wykes T, Sturt E. The measurement of social behaviour in psychiatric patients: an assessment of the reliability and validity of the SBS schedule. Br J Psychiatry.1986;148(1):1–11.

- 168. Magliano L, Fadden G, Madianos M, et al Burden on the families of patients with schizophrenia: results of the BIOMED I study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol.1998;33:405–412.

- 169. Jaeger J, Berns SM, Czobor P. The multidimensional scale of independent functioning: a new instrument for measuring functional disability in psychiatric populations. Schizophr Bull.2003;29(1):153–168.

- 170. Hogarty GE, Flesher S, Ulrich R, et al Cognitive enhancement therapy for schizophrenia: effects of a 2-year randomized trial on cognition and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry.2004;61(9):866–876.

- 171. Byrne R, Davies L, Morrison AP. Priorities and preferences for the outcomes of treatment of psychosis: a service user perspective. Psychosis. 2010;2(3):210–217.

- 172. Wood L, Alsawy S. Recovery in psychosis from a service user perspective: a systematic review and thematic synthesis of current qualitative evidence. Community Ment Health J.2018;54(6):793–804.