Highlights

The most common method of distributing naloxone is through community opioid education and naloxone distribution (OEND) programs and community pharmacies via a standing order/statewide protocol.

Most distribution models report feasibly increasing individual access to naloxone but do not report health/economic outcomes data associated with naloxone distribution.

Commonly cited barriers to naloxone distribution program success are cost, administrative support, and inability to collect outcomes data.

Policymakers and state health officials should seek to create a standardized process of identifying naloxone distribution programs and collecting, reviewing, and reporting demographic and clinical data pertaining to naloxone access and clinical outcomes.

Introduction

The United States declared a national opioid epidemic in October 2017. Since then, opioid overdose deaths (OODs) have continued to rise at an alarming rate, with a near doubling of deaths between 2016 and 2022. This ongoing tragedy has a profound economic impact on the US health care system and a psychosocial toll on families/friends who have lost loved ones to OODs. As stated by the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), “the overdose crisis is national, but the impact is personal.” Thus, implementing effective interventions for reducing OODs is a matter of public health urgency.

According to the HHS, increasing naloxone distribution is critical to reducing OODs and helping end the opioid epidemic., As Dr. Volkow stated in 2022, “We don’t need to keep asking if these things work. Instead, we must find ways to help providers, people, and communities overcome the barriers to implementing these valuable interventions.” Of the irrefutably effective interventions discussed, naloxone provision tops the list, followed by other harm reduction services such as prescribing medications for opioid use disorder, utilizing contingency management for treating co-occurring stimulant use disorders, provision of syringe service programs (SSPs),, and educational interventions to prevent substance use disorders (SUDs). While there have been recent strides toward improving naloxone distribution, such as the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of 4 and 3 mg naloxone hydrochloride nasal spray for over the counter (OTC) use in March and July 2023,, there remains much work to be done.

Numerous barriers related to access, affordability, and stigma continue to hinder widespread naloxone distribution.- State opioid response grants aim to overcome these barriers by supporting efforts to scale up naloxone distribution/access. Grant awardees are required to create naloxone distribution and saturation plans to ensure naloxone reaches those most likely to witness an overdose and in the locations where they are most likely to occur. Unfortunately, current naloxone distribution efforts fall short at tracking who gets naloxone relative to their risk of experiencing or witnessing an overdose and the potential impact on preventing OODs. This is partially due to the existence of many naloxone distribution pathways, such as community pharmacies via state standing orders, hospitals and emergency departments (EDs) after admission for opioid overdoses,- first responders (emergency medical services [EMS], firefighters, police officers),, overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) programs in health care (eg, clinics, hospitals) and non-health care settings (eg, community-based harm reduction programs [CHRPs], public libraries, schools, jails),- and static, anonymous supply sources (eg, vending machines, kiosks)., The existence of many distribution pathways makes it logistically difficult to measure naloxone distribution to ensure it is reaching the intended population. Thus, developing measures to help understand how these different distribution strategies impact naloxone access to persons at risk of OOD is a high public health priority.

Despite the existence of many naloxone distribution pathways, recent evidence found that all US states have underdeveloped naloxone distribution efforts and that the method of naloxone delivery has large effects on the probability of naloxone use and number of OODs averted. Due to an ongoing need to increase widespread naloxone distribution, the purpose of this scoping review was to identify and compare different naloxone distribution models in the United States. This allows for a critical review of each model’s strengths and limitations, which will further assist with policy development and implementation to address the US opioid epidemic.

Methods

Design

This scoping review report was constructed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) checklist.

Search Strategy

Search terms were developed from 3 concepts: (1) narcan/naloxone; (2) OEND; and (3) naloxone distribution setting. A combination of these keywords and controlled vocabulary were utilized to develop the search strategy. Four databases from database inception to May 28, 2023: (1) PubMed/Medline (National Library of Medicine), (2) Embase (Elsevier), (3) Scopus (Elsevier), and (4) Cochrane library. The search strategy developed in PubMed/Medline was translated to the other databases. Supplemental Appendix 1 contains the full search strategies for all databases. All identified records from all sources were imported into citation management software EndNote and deduplicated before screening began.

Eligibility Criteria

The report needed to be written in English and published in a legitimate journal (eg, indexed in PubMed, Directory of Open Access Journals, or associated with a professional or health care organization) to avoid predatory or questionable journals. Reports from all years searched, and all study designs were eligible for inclusion. Reports were excluded if they did not report data related to naloxone distribution within the United States. These criteria were designed for a broad search that could capture all high-quality and relevant information about US naloxone distribution methods.

Study Selection and Data Extraction

The title and abstract of each record were independently screened for eligibility by 6 reviewers (BE, LR, US, JT, KV, and SZ). The standardized screening tool (Supplemental Appendix 2) was designed specifically for this study to identify whether the record contained relevant data for: (1) naloxone distribution method; (2) written in English; and (3) conducted in a US setting. Reviewers met to discuss and agree through consensus whether each record met the screening criteria. Unclear records were included for a full-text review.

Each record that met the screening criteria was included for a full-text review. Each full-text article was independently reviewed by 6 reviewers (BE, LR, US, JT, KV, and SZ). The standardized data charting tool (Supplemental Appendix 3) was also designed specifically for this study. Reviewers met to discuss and agree through consensus whether each record should ultimately be included in the review. In cases where it was unclear whether a record should be included, 2 additional reviewers (NV and DRA) also reviewed the record and sought consensus. It was not necessary to contact authors for additional details for any records identified in this review.

Data were collected on the study design, naloxone distribution setting, distribution method, health care professionals involved, naloxone formulation, and study location. The reported outcomes associated with naloxone distribution and emergent themes related to the strengths/weaknesses of the distribution models were described upon reviewing the reported strengths/weaknesses of the full-text articles. Each of the many distribution settings identified were later categorized into broader categories (Community Pharmacy, Community-based OEND, or Health-system) to clearly organize the discussion regarding emergent themes related to each overarching distribution setting, while still reporting the specific setting type in Table 1 as described by each included article. Since several studies described naloxone distribution across multiple settings (CHRPs, health care facilities, non-health care facilities [eg, correctional facilities, educational institutions], and/or passive models [eg, vending machines, kiosks]) and utilized different methods to distribute naloxone, multiple distribution settings and method types could be selected during the data collection process. Since CHRPs often offer multiple harm reduction services outside of OEND ([1] SSPs; [2] safer smoking supplies/distribution; [3] drug-checking education, for example, fentanyl/xylazine and other assay test strips; [4] integrated reproductive health education, services/supplies, and sexually transmitted infection screening, prevention, and treatment; and [5] onsite access or immediate accessible referral to wound care supplies/services), we categorized the setting as CHRP if the paper described the program as one that provided OEND (± other harm reduction services). The method of distribution could be categorized as utilizing an “OEND distribution model” if a similar OEND model was used in any of the many settings described.

Results

Overview of Search Results

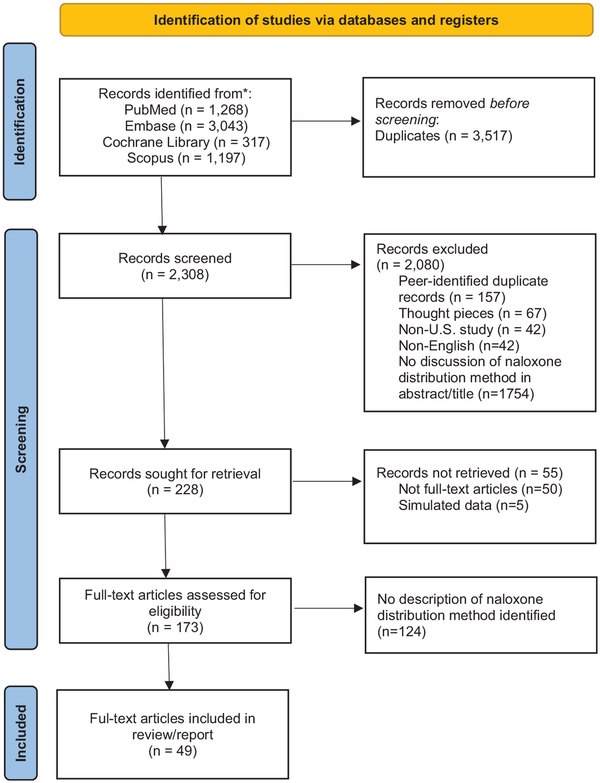

Of 5825 publications identified, 2308 were included for title/abstract screening (Figure 1). Of these, 2135 either did not meet inclusion criteria or were irrelevant; thus, 173 articles underwent full-text screening. Of these, 49 studies were included in this review (Supplemental Appendix 4).-,,,,,,-

Figure 1

PRISMA 2020 flow diagram for new systematic reviews, which included searches of databases and registers only.

Characteristics of Included Studies

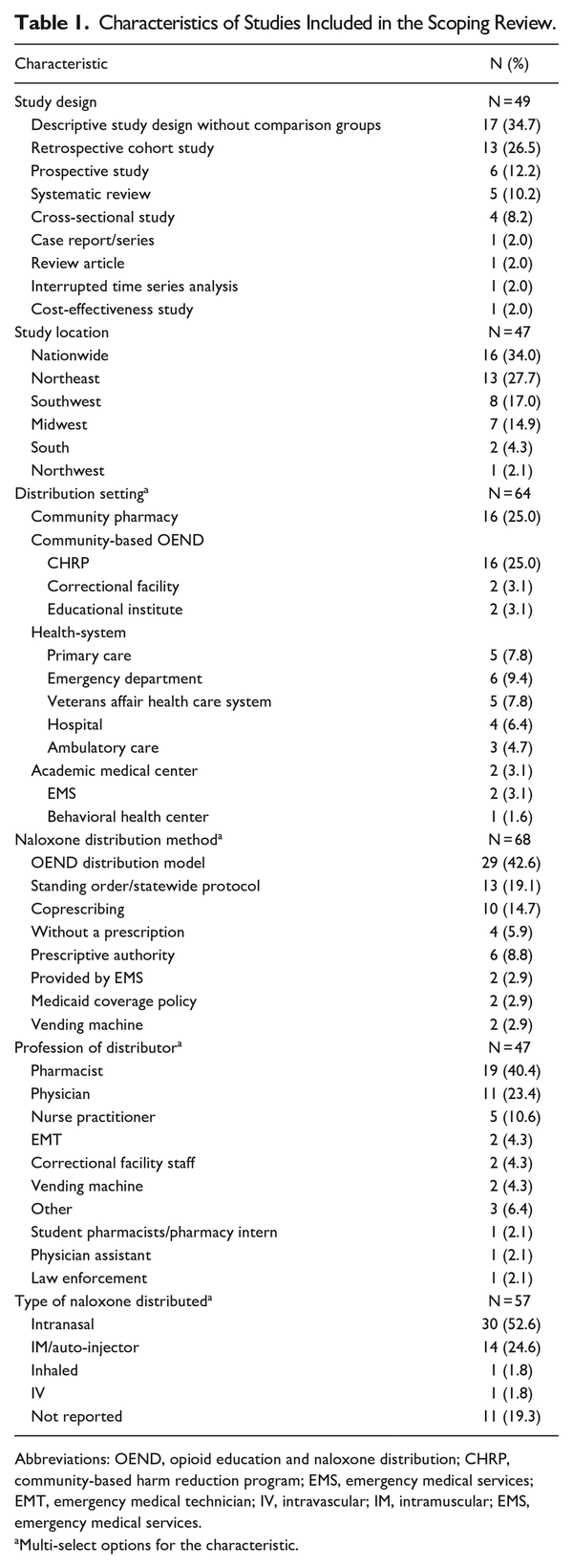

Descriptive characteristics of included studies are reported in Table 1. Most were descriptive studies (n = 17; 34.7%) or retrospective cohort studies (n = 13; 26.5%). Most studies started before the opioid epidemic was announced as a national epidemic (n = 28; 68%), but of those studies that started before October 2017, 42% of them ended after that time (n = 12/28). About a third of the studies included describe naloxone distribution patterns/characteristics across multiple states (n = 16; nationwide). A quarter of the included studies took place in the northeast (n = 13; New York, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island), with the next highest number of included studies taking place in the southwest (n = 8; California, Colorado, Nevada, New Mexico), Midwest (n = 7; Michigan, Chicago, Ohio), with fewest from the south (n = 2; Texas and North Carolina) and Northwest (n = 1; Washington).

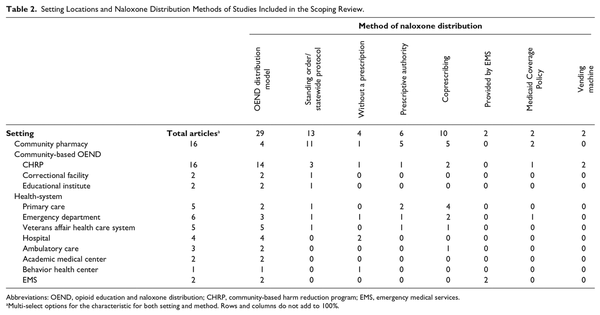

Distribution Setting and Method

Table 2 provides a breakdown of naloxone distribution methods across various settings. Many studies described multiple distribution methods and/or setting locations. Most studies described community-based OEND (n = 20), either through CHRPs (n = 16), correctional facilities (n = 2), or educational institutes (n = 2). Sixteen studies discussed community pharmacy distribution. Many different health-system locations were identified, including: primary care (n = 5), ED (n = 6), US Department of Veterans Affairs (n = 5), hospital (n = 4), ambulatory care (n = 3), academic medical center (n = 2), EMS (n = 2), or behavior health center (n = 1). These are discussed under Health-System Naloxone Distribution. Naloxone distribution occurring in CHRPs often utilized an OEND infrastructure, while most community pharmacies described naloxone distribution taking place via a standing order/statewide protocol.

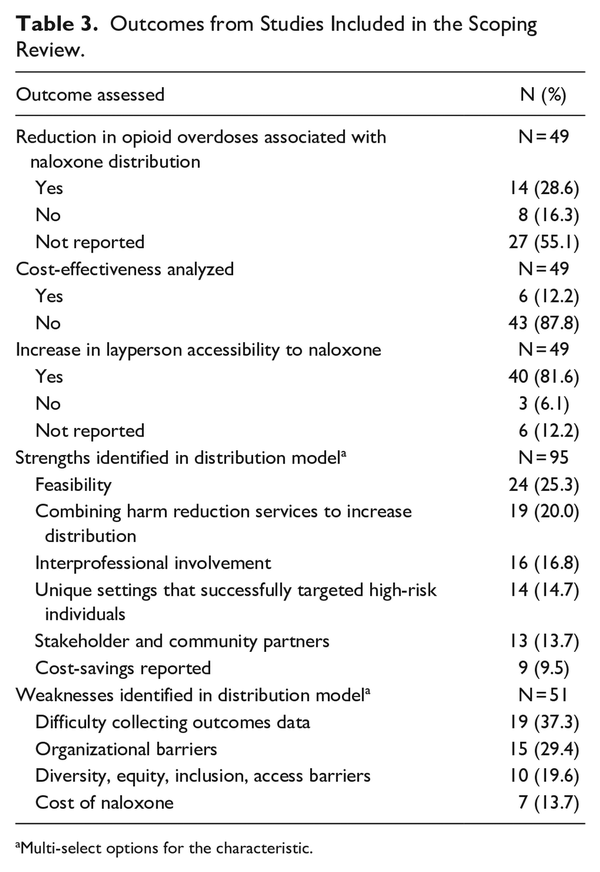

Outcomes

The outcomes assessed and strengths and weaknesses of the distribution models in the included studies are reported in Table 3. Most studies did not report on whether naloxone distribution improved opioid-related harm, for example, opioid overdose/OOD reduction (n = 27, 55.1%) or the cost-effectiveness of the naloxone distribution method (n = 43, 87.8%). Increase in naloxone access was reported in most studies (n = 40, 81.6%). A common strength of the distribution models was feasibility via a standing order/statewide protocol or prescriptive authority (n = 24, 25.3%). Many also reported on how interprofessional involvement (n = 16, 16.8%) and key working partner engagement (n = 13, 13.7%) is key to program success. Some described a strength of being able to distribute naloxone within settings that are uniquely equipped to target high-risk individuals (n = 14, 14.7%). However, some studies noted organizational barriers (n = 15, 29.4%) as a weakness to achieving feasibility, as well as barriers in ensuring equitable distribution (n = 10, 19.6%). Cost was also reported as a limitation to increasing naloxone distribution (n = 7, 13.7%).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the only scoping review to broadly describe all types of naloxone distribution models in the United States. These findings highlight the many settings and modes of naloxone distribution, as well as their strengths/limitations.

Community Pharmacy Naloxone Distribution

Articles identified from this review report that community pharmacies are able to increase naloxone distribution when utilizing a standing order/statewide protocol. Additionally, 1 population-based, state-level cohort study conducted between 2011 and 2017 found that the implementation of a naloxone coprescription mandate was associated with approximately 7.75 times more dispensed naloxone prescriptions, equating to an estimated 214 additional naloxone prescriptions dispensed per month. This study also reported that third-party prescribing or standing order laws were associated with a 37% mean increase in naloxone dispensing. States with naloxone access laws (NALs) also had a 15% lower incidence of OODs on average than states without these laws. These data provide strong support to justify the implementation of standing order/statewide protocols and naloxone coprescribing mandates in all states to further increase naloxone dispensing rates. One retrospective cohort study conducted in Ohio between July 2014 and January 2017 found that naloxone dispensing rates increased most in low-employment and high-poverty counties following the implementation of a standing order/statewide protocol, demonstrating this model is effective at increasing distribution for underserved communities. Regions with higher fatality rates may have fewer pharmacies participating in statewide standing orders, emphasizing the need to mandate standing orders across all pharmacies.

While pharmacist prescriptive authority and coprescribing both increase the number of naloxone prescriptions, Cariveau et al. found that only one third of these prescriptions are filled. This is likely attributable to multiple factors; for example, pharmacies must have a sufficient supply of naloxone to fulfill standing orders or dispense naloxone pursuant to a prescription; however, many pharmacies do not have sufficient supply to meet the current demand.,, In some states, up to half of pharmacies may not participate in a standing order or may lack access to readily available naloxone., Some pharmacies have increased administrative burdens related to increasing naloxone supply/dispensing, which may translate to reduced naloxone access at this level., Some pharmacists may hold personal beliefs and stigmas that impact their willingness to dispense naloxone. Others may be reluctant to dispense naloxone out of concern for legal repercussions since not all states provide immunity to the prescriber and dispenser of naloxone, despite research demonstrating that states with Good Samaritan laws (GSLs) have a lower incidence rate of OODs. Overall, for all community pharmacies to feasibly adopt and implement standing orders/statewide protocols/coprescribing mandates, barriers pertaining to naloxone supply, administrative support, and patient/prescriber immunity must be eliminated.

There are opportunities to improve opioid and naloxone coprescribing. Current coprescribing mandates only serve to ensure physicians and providers offer naloxone prescriptions to patients they are currently prescribing opioids to. As such, coprescribing mandates appear to only reduce OODs for individuals using prescription opioids, not individuals using illicit opioids. There may be benefit in expanding coprescribing mandates to include individuals with any type of SUD, particularly since fentanyl is the main driver of OODs, and fentanyl is commonly found in opioid and nonopioid illicit substances. Since community pharmacy records do not allow for an easy identification of whether an individual is diagnosed with a SUD and/or at risk of OOD due to illicit substance use, community-based OEND and health-systems, discussed in the next sections, are critical for targeting these additional at-risk persons.

Community-Based OEND

According to The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, OEND is 1 of 6 core practice areas that give life to harm reduction approaches, initiatives, programs, and services. CHRPs describe harm reduction organizations where people with lived and living experience lead the planning and oversight, program development and evaluation, and resource/funding allocation for an organization’s harm reduction initiatives, programs, and services. CHRPs offer core practices areas as permitted by law (eg, SSPs), including OEND.

Based on this review, community-based OEND accounts for a large proportion of naloxone distribution pathways in the United States and have contributed to significant positive health and economic outcomes. A decision analytical model comparing the effectiveness, efficiency, and geospatial health equity of alternative naloxone distribution strategies across multiple OEND programs in Rhode Island between January 2016 and December 2022 found that programs utilizing a demand-based approach that targeted persons at highest risk of overdose (those who inject drugs or use illicit substances) were able to reduce the number of witnessed OODs by an estimated 25.3% annually with an estimated cost-savings of anywhere between $27,312 and $44,185 per OOD averted. This suggests that OEND programs that use geospatial data to determine naloxone demand among different regions may be more successful in improving naloxone distribution and reducing OODs. In addition, Townsend et al. found that high naloxone distribution to first responder groups (police officers, firefighters, EMS) and people likely to witness or experience overdose (“laypeople”) was cost-effective and resulted in mortality reduction by benefiting those whose witnesses do not call EMS.

A recent review on the policy landscape for naloxone distribution highlights how robust OEND networks increase naloxone distribution rates far more than that of pharmacy dispensing rates, suggesting pharmacy access laws are currently inadequate or under-implemented. For example, New York reportedly had the highest community naloxone distribution rate of any state prior to 2019, and these rates were higher than pharmacy dispensing rates for all states. New York has over 800 opioid overdose prevention programs that are financially supported by the New York State Department of Health, which suggests that OEND programs are a main driver for community naloxone provision.

OEND programs outside of pharmacies are unique in that they engage a variety of people who may witness opioid overdose(s), including family members. Bagley et al. reports that family members, including those who use substances and those that do not use substances, made up over a quarter of total program enrollees in Massachusetts (10,833/30,801 enrollees). Over half of enrolled family members did not use unregulated drugs and 20% of them engaged in rescue attempts following naloxone administration training, most often to nonfamily members (eg, friends). Family members were more likely to be rescued by people who did not originally intend to rescue family members, and nonfamily members were rescued by people who intended to rescue family members. This highlights the importance of improving naloxone access to laypersons, especially since other distribution programs such as community pharmacies have focused mainly on distributing to individuals prescribed opioids and subsequently identified as high risk for OOD. Community pharmacy protocols, while also successful at increasing naloxone distribution rates, may not do as well in targeting naloxone distribution to individuals who are not substance users. Thus, ongoing funding for OEND programs is vital for improving naloxone distribution to friends/family of people who use drugs (PWUD) at risk of OOD.

While descriptive studies on community-based OEND programs often describe feasibility of naloxone distribution as a strength, issues related to equitable distribution were raised. For example, one descriptive analysis by Zang et al. reported a surge in OODs immediately after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic among non-Hispanic Black people in Massachusetts, with no compensatory increase in naloxone kit distribution. Non-Hispanic White and Hispanic individuals on the other hand continued to have stable OOD rates, and naloxone kit distribution continued to increase for this population. Massachusetts is one of the few states that collects demographic information for each naloxone kit distributed via OEND programs, allowing for the assessment of the disparities in naloxone access over time. Future and existing naloxone distribution programs should ensure demographic information is collected and reported on to inform state policy makers on the gaps in naloxone supply and demand. Another study by Zang et al. discussed the need for new measures to continuously help identify and address emerging “hotspot” communities, since the opioid epidemic is constantly evolving.

Findings from this review highlight how OEND programs can be implemented successfully to target potentially overlooked populations, such as formerly incarcerated individuals who are often at high risk of drug overdose. Two studies identified in this review describe OEND programs in correctional facilities that provide naloxone and education to people as they exit the correctional system, empowering them to protect themselves and others upon release., In California specifically, the statewide standing order protocol allows naloxone to be distributed throughout the county of San Francisco, including the county jail. Wenger et al. described how participants of this OEND program felt comfortable acting as peer educators and “overdose responders” in their community upon release from incarceration, demonstrating the value of these programs on improving self-worth and reintegration into the community. However, Showalter et al. analyzed 3 of these programs in California and found several institutional barriers that impeded naloxone distribution. For example, correctional facilities typically emphasize abstinence from drugs and restrict property, movement, and medication, which makes implementing and maintaining an effective program challenging.

Static modes of naloxone distribution implemented by CHRPs have also been successful. Allen et al. described the impact of their public health vending machines that dispensed nearly 2,000 naloxone doses in 12 months. Arendt et al. described how the implementation of an automated harm reduction dispensing machine (dispensing naloxone in addition to other harm reduction supplies such as fentanyl test strips) led to more dispensing of naloxone and fentanyl test strips than any other SSP in the country. These modes of naloxone distribution may be particularly effective at increasing naloxone access since they maintain patient anonymity, thus overcoming barriers related to stigma. Additionally, implementing vending machines is an easy way to increase naloxone access points, an issue that became increasingly relevant during the COVID-19 pandemic when many in-person OEND programs were forced to either pause services or transition to telephone- or video-based initiatives. The opioid crisis worsened significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, but paved the way for the development and implementation of successful virtual and telephone-based OEND programs.,

Lastly, some studies described OEND through colleges and universities. Individuals may be reluctant to request harm reduction services from school administrators or campus health professionals and, as evaluated by Brown et al., peer-to-peer distribution is an effective way to dispense naloxone and provide overdose education to a high-risk group. One OEND program in Maryland described their program as feasible and low-cost when using the assistance of student volunteers. Hill et al. described distributing naloxone to residence halls and the police department at a college campus, but described challenges related to ongoing costs associated with naloxone acquisition, distribution, education, and staffing. Since OEND programs are primarily financed through federal and state grant funding, with state discretion on funding allocation, policymakers should work to ensure permanent and adequate funding is provided based on previous and emerging data trends regarding OOD and naloxone dispensing rates.

Health-System Naloxone Distribution

Health-system studies identified in this scoping review were conducted in various settings, including primary care, EDs, hospitals, and ambulatory clinics such as obstetrics/gynecology. Primary care studies reported adopting an OEND framework by identifying patients at high risk of OODs in clinic and referring them for follow-up individual/group visits., Most studies reported a multidisciplinary team approach was key to successfully identifying patients to dispense naloxone to in this setting. For example, Watson and colleagues utilized clinical pharmacists and informatic service personnel to create reports to identify persons on chronic opioid therapy at risk of OOD. Clinical pharmacists would then reach out to identified individuals and provide education on the benefits of naloxone and send prescriptions to the primary care provider if the patient was agreeable to receiving naloxone. This highlights the value of financially supporting multidisciplinary services to successfully operate naloxone distribution programs. Health-systems that adopt this type of program may consider optimizing informatic reports to include all patients with SUDs to avoid missing non-prescription opioid users who may also be at risk of OOD and benefit from this type of intervention.

Similar naloxone distribution models are described in the ED setting. For example, Dora-Laskey et al. reported successful implementation of a statewide ED take-home naloxone program across 9 hospital EDs in Michigan utilizing interprofessional network building and training. Over 140 providers were trained and participated in the program, including pharmacy, nurse, and physician champions. Samuels et al. described the success of Rhode Island’s statewide, interhospital ED naloxone distribution program, which paired naloxone distribution with a peer recovery coach. However, despite reported feasibility and positive findings, ED naloxone distribution uptake has been low.,, Based on reported limitations of the ED studies included in this review, it takes a strong network of clinical champions who have administrative support to implement such a program. Dora-Laskey et al. discussed how hospital administrators may question the legality of ED dispensing or whether it is cost-effective. The program described by Dora-Laskey was supported by grant funding; the authors discuss how the program would not have been feasible without salary support to protect nonclinical time for participating clinicians, as well as the provision of subsidized intranasal naloxone. It is especially difficult to justify ongoing funding for these types of programs without a systematic means of collecting/assessing health outcomes following naloxone distribution (eg, rehospitalization/OODs).

Other EMS personnel can also feasibly distribute naloxone, with 1 study by LeSaint et al. reporting the ability of EMS technicians and paramedics to distribute over 1,000 naloxone kits over the course of a year, similarly citing that interprofessional collaboration with multiple entities was key to the program’s success. Train et al. found it was feasible to provide naloxone during inpatient hospitalization, with the assistance of funding through the state’s copayment assistance program and vouchers. Their interprofessional approach identified high-risk patients, distributed a naloxone kit to their bedside, and provided education prior to discharge. Nguyen et al. found this method was feasible when mobilizing trained student pharmacists as members of the interprofessional OEND team.

As previously mentioned, naloxone distribution can be customized to unique settings and populations at higher risk of experiencing or witnessing an overdose. Duska and Goodman described point-of-care naloxone distribution among pregnant women at an ambulatory obstetric clinic at a rural academic health center, which was well-received among staff and patients. A take-home naloxone program at an outpatient behavioral health center in New York provided intranasal formulations because hypodermic needles were viewed as a safety risk. Katzman et al. demonstrated how take-home naloxone as part of an OEND program within an outpatient opioid treatment program (OTP) is associated with reduced OODs, concluding that policy makers may consider mandating OEND in OTPs.

Overall, despite guideline recommendations, prescribing/dispensing naloxone to patients at risk of opioid overdose is infrequent.,- Few states have coprescribing laws, and prescribers are often only encouraged to prescribe naloxone to individuals at risk of OOD, which can be defined in many ways and easily missed during routine patient care encounters. While not all opioid users are at risk of OOD, it is still surprising to see such a high discrepancy between national opioid dispensing rates vs. national naloxone dispensing rates. For example, the opioid dispensing rate per 100 persons in 2022 was 39.5 versus 0.5 for the naloxone dispensing rate per 100 persons. This would suggest that issues pertaining to stigma of needing naloxone and/or cost continue to drive overall low naloxone prescribing/dispensing rates across health-systems.

Future Directions

It is important for states to continuously collect, report, and assess data pertaining to the quantity and quality of existing naloxone distribution programs. Findings from this study suggest that naloxone distribution programs are generally feasible when there is support from working partners, but that there are not systems in place to reliably collect data pertaining to naloxone distribution operations and their associated health/economic outcomes.

Wheeler et al. described the various naloxone distribution programs offered by 136 organizations with assistance from the National Harm Reduction Coalition, an organization that empowers communities to create and expand evidence-based harm reduction programs. They report how the number of OENDs nationally expanded substantially between 1996 and 2014, as well as the number of laypersons that received prescribed naloxone kits, and the number of reported opioid overdose reversals. This growth is attributed to the growth in the types of institutions that have become involved in naloxone distribution, expanding beyond SSPs to substance use treatment facilities, Veterans Administration health care systems, health departments, primary care clinics, and pharmacies. Unfortunately, these programs faced challenges due to the increasing cost of naloxone, and there is still a substantial need to expand naloxone distribution and training to laypersons to extend naloxone access to those who may witness overdoses.,,

Though there are mixed results, cumulatively, the development of NALs across all states has been associated with improved naloxone access and reduced opioid overdoses. Specifically, NALs combined with GSLs with more expansive legal protections are associated with lower rates of OODs. This is important to consider since access to and the use of naloxone is only 1 step in a series of steps needed to prevent OODs. PWUD who have just overdosed still need to receive prompt medical treatment after naloxone is administered, and PWUD are more likely to fear law enforcement and choose to handle overdoses without help. Thus, policy work to promote enactment of the most expansive form of GSLs will be important to reduce OODs alongside efforts to promote and sustain naloxone distribution programs. Overall, more studies are needed on what naloxone distribution model factors are associated with reductions in OODs. Since equitable access to naloxone is an ongoing issue, with socially disadvantaged individuals having poorer access and higher risk for OOD, more studies are also needed on working partners’ perception of current naloxone distribution programs. These perspectives would provide breadth and understanding regarding the underlying barriers and facilitators of equitable access to naloxone programs by socially disadvantaged and marginalized populations.

Lastly, it is important to avoid overestimating the potential impact of naloxone’s newly approved OTC status on distribution. While reclassifying naloxone as OTC may increase its availability via multiple delivery modalities (for example, supermarkets, gas stations, vending machines), and potentially circumvent the social stigma around obtaining prescription naloxone, cost will likely remain a barrier for years to come before market competition hopefully leads to improvements in affordability. It is also difficult to predict to what degree increased availability will translate to increases in nondispensed purchases. For example, in 2016, naloxone was rescheduled as an OTC drug in Australia, and while total naloxone supply to community pharmacies in Australia increased in the following 2 years, there was no significant change in the volume of nondispensed naloxone. Taking this into consideration, successful distribution models described in this review should be further developed/supported by policymakers as we continue to gather data on the impact of the FDA’s OTC naloxone reclassification.

Limitations

Since this was a scoping review and not a systematic review, a quality assessment was not conducted for the studies included. Future research may consider conducting a systematic review to provide further insights on the strengths and weaknesses of current naloxone distribution models in the United States. This study did not investigate what factors are associated with successful naloxone distribution (eg, increase in patient access, reduction in OODs, cost savings). Lastly, a broad search strategy was used, but it is possible additional articles were missed based on slight differences in terminology.

Conclusions

There are many modes of distributing naloxone in the United States. Findings of this study suggest naloxone is mainly distributed via OEND models as part of CHRPs, followed by community pharmacies with standing order/statewide protocols. Health-systems with coprescribing laws and/or naloxone-prescribing protocols also report successful naloxone distribution efforts when there is strong interprofessional involvement and support from working partners. Cited weaknesses from most settings suggest that policymakers should strive to develop a standardized means of identifying naloxone distribution programs and implement processes for collecting, reviewing, and reporting demographic and clinical data pertaining to naloxone access and health outcomes. This will allow for a better assessment of individual program funding/resource needs and help policymakers determine what actions are needed to support intervention sustainability.

The authors would like to thank the following Doctor of Pharmacy candidates: Leah A. Rath, Jackie A. Tan, Uju Sampson, Sahr Bin-Zager, and Kayleen Velasco; who devoted their time to helping develop the search strategy and identifying and screening articles for study inclusion.

Author contribution NV contributed to conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, validation, visualization, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. DRA contributed to conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, validation, writing – review & editing. BE contributed to formal analysis, investigation, methodology, validation, writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Compliance, Ethical Standards, and Ethical Approval There are no human participants in this article and informed consent is not required.

Nina Vadiei

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3984-0317

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online at the SAJ website http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/29767342241289008.

References

- 1. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Ongoing emergencies & disasters. 2024. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/about-cms/what-we-do/emergency-response/current-emergencies/ongoing-emergencies#:~:text=On%20Thursday%20October%2026%2C%202017,is%20a%20national%20health%20emergency.%E2%80%9D

- 2. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Drug overdose death rates. 2024. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

- 3. Jones CM, Zhang K, Han B, et al. Estimated number of children who lost a parent to drug overdose in the US From 2011 to 2021. JAMA Psychiatry. 2024;81(8):789–796. doi:

- 4. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Overdose prevention strategy. 2024. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/overdose-prevention/

- 5. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. U.S. surgeon general’s advisory on naloxone and opioid overdose. 2022. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.hhs.gov/surgeongeneral/reports-and-publications/addiction-and-substance-misuse/advisory-on-naloxone/index.html

- 6. Linas BP, Savinkina A, Madushani R, et al. Projected estimates of opioid mortality after community-level interventions. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037259. doi:

- 7. National Insitute on Drug Abuse. Five areas where “More Research” isn’t needed to curb the overdose crisis. 2022. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://nida.nih.gov/about-nida/noras-blog/2022/08/five-areas-where-more-research-isnt-needed-to-curb-overdose-crisis

- 8. Lambdin BH, Bluthenthal RN, Wenger LD, et al. Overdose education and naloxone distribution within syringe service programs—United States, 2019. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(33):1117–1121. doi:

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Safety and effectiveness of syringe services programs. 2024. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/syringe-services-programs/php/safety-effectiveness.html#:~:text=Syringe%20services%20programs%20can%20reduce,and%20providing%20naloxone%20to%20them

- 10. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves first over-the-counter naloxone nasal spray. 2023. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-first-over-counter-naloxone-nasal-spray#:~:text=Today%2C%20the%20U.S.%20Food%20and,for%20use%20without%20a%20prescription

- 11. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. FDA approves second over-the-counter naloxone nasal spray product. 2023. Accessed October 4, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-second-over-counter-naloxone-nasal-spray-product

- 12. Stoltman JJK, Terplan M. OTC naloxone is a baby step toward making the life-saving medication accessible. STAT. 2023. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.statnews.com/2023/04/17/otc-narcan-naloxone-price-availability/

- 13. Baptiste-Roberts K, Hossain M. Socioeconomic disparities and self-reported substance abuse-related problems. Addict Health. 2018;10(2):112–122. doi:

- 14. Matsuzaki M, Vu QM, Gwadz M, et al. Perceived access and barriers to care among illicit drug users and hazardous drinkers: findings from the Seek, Test, Treat, and Retain data harmonization initiative (STTR). BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):366. doi:

- 15. Biancarelli DL, Biello KB, Childs E, et al. Strategies used by people who inject drugs to avoid stigma in healthcare settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;198:80–86. doi:

- 16. Paquette CE, Syvertsen JL, Pollini RA. Stigma at every turn: health services experiences among people who inject drugs. Int J Drug Policy. 2018;57:104–110. doi:

- 17. Green TC, Case P, Fiske H, et al. Perpetuating stigma or reducing risk? Perspectives from naloxone consumers and pharmacists on pharmacy-based naloxone in 2 states. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S19-S27 e4. doi:

- 18. Sugarman OK, Hulsey EG, Heller D. Achieving the potential of naloxone saturation by measuring distribution. JAMA Health Forum. 2023;4(10):e233338. doi:

- 19. Rawal S, Osae SP, Cobran EK, Albert A, Young HN. Pharmacists’ naloxone services beyond community pharmacy settings: a systematic review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2023;19(2):243–265. doi:

- 20. Lai RK, Friedson KE, Reveles KR, et al. Naloxone accessibility without an outside prescription from U.S. community pharmacies: a systematic review. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2022;62(6):1725–1740. doi:

- 21. Train MK, Patel N, Thapa K, Pasho M, Acquisto NM. Dispensing a naloxone kit at hospital discharge: a retrospective QI project. Am J Nurs. 2020;120(12):48–52. doi:

- 22. Dora-Laskey A, Kellenberg J, Dahlem CH, et al. Piloting a statewide emergency department take-home naloxone program: Improving the quality of care for patients at risk of opioid overdose. Acad Emerg Med. 2022;29(4):442–455. doi:

- 23. Gunn AH, Smothers ZPW, Schramm-Sapyta N, Freiermuth CE, MacEachern M, Muzyk AJ. The emergency department as an opportunity for naloxone distribution. West J Emerg Med. 2018;19(6):1036–1042. doi:

- 24. Samuels EA, Baird J, Yang ES, Mello MJ. Adoption and utilization of an emergency department naloxone distribution and peer recovery coach consultation program. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(2):160–173. doi:

- 25. Moore PQ, Cheema N, Celmins LE, et al. Point-of-care naloxone distribution in the emergency department: a pilot study. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2021;78(4):360–366. doi:

- 26. Sindhwani MK, Friedman A, O’Donnell M, Stader D, Weiner SG. Naloxone distribution programs in the emergency department: a scoping review of the literature. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open. 2024;5(3):e13180. doi:

- 27. Rando J, Broering D, Olson JE, Marco C, Evans SB. Intranasal naloxone administration by police first responders is associated with decreased opioid overdose deaths. Am J Emerg Med. 2015;33(9):1201–1204. doi:

- 28. Townsend T, Blostein F, Doan T, Madson-Olson S, Galecki P, Hutton DW. Cost-effectiveness analysis of alternative naloxone distribution strategies: first responder and lay distribution in the United States. Int J Drug Policy. 2020;75:102536. doi:

- 29. Weiner J, Murphy SM, Behrends C. Expanding access to naloxone: a review of distribution strategies. 2019. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://ldi.upenn.edu/our-work/research-updates/expanding-access-to-naloxone-a-review-of-distribution-strategies/

- 30. Naumann RB, Durrance CP, Ranapurwala SI, et al. Impact of a community-based naloxone distribution program on opioid overdose death rates. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;204:107536. doi:

- 31. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Servies Administration. Harm Reduction Framework. Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2023.

- 32. Arendt D. Expanding the accessibility of harm reduction services in the United States: measuring the impact of an automated harm reduction dispensing machine. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2023;63(1):309–316. doi:

- 33. Allen ST, O’Rourke A, Johnson JA, et al. Evaluating the impact of naloxone dispensation at public health vending machines in Clark County, Nevada. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):2692–2700. doi:

- 34. Irvine MA, Oller D, Boggis J, et al. Estimating naloxone need in the USA across fentanyl, heroin, and prescription opioid epidemics: a modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2022;7(3):e210-e218. doi:

- 35. Bohler RM, Freeman PR, Villani J, et al. The policy landscape for naloxone distribution in four states highly impacted by fatal opioid overdoses. Drug Alcohol Depend Rep. 2023;6:100126. doi:

- 36. Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–473. doi:

- 37. The EndNote Tean. EndNote. Version EndNote 20. Clarivate; 2013.

- 38. Gangal NS, Hincapie AL, Jandarov R, et al. Association between a state law allowing pharmacists to dispense naloxone without a prescription and naloxone dispensing rates. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1920310. doi:

- 39. Behar E, Bagnulo R, Coffin PO. Acceptability and feasibility of naloxone prescribing in primary care settings: a systematic review. Prev Med. 2018;114:79–87. doi:

- 40. Showalter D, Wenger LD, Lambdin BH, Wheeler E, Binswanger I, Kral AH. Bridging institutional logics: implementing naloxone distribution for people exiting jail in three California counties. Soc Sci Med. 2021;285:114293. doi:

- 41. Wheeler E, Jones TS, Gilbert MK, Davidson PJ, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to laypersons—United States, 2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64(23):631–635.

- 42. Sohn M, Talbert JC, Huang Z, Lofwall MR, Freeman PR. Association of naloxone coprescription laws with naloxone prescription dispensing in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(6):e196215. doi:

- 43. Zang X, Bessey SE, Krieger MS, et al. Comparing projected fatal overdose outcomes and costs of strategies to expand community-based distribution of naloxone in Rhode Island. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2241174. doi:

- 44. Zang X, Macmadu A, Krieger MS, et al. Targeting community-based naloxone distribution using opioid overdose death rates: a descriptive analysis of naloxone rescue kits and opioid overdose deaths in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;98:103435. doi:

- 45. Bagley SM, Forman LS, Ruiz S, Cranston K, Walley AY. Expanding access to naloxone for family members: the Massachusetts experience. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2018;37(4):480–486. doi:

- 46. Bailey AM, Wermeling DP. Naloxone for opioid overdose prevention: pharmacists’ role in community-based practice settings. Ann Pharmacother. 2014;48(5):601–606. doi:

- 47. Cariveau D, Fay AE, Baker D, Fagan EB, Wilson CG. Evaluation of a pharmacist-led naloxone coprescribing program in primary care. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2019;59(6):867–871. doi:

- 48. Dahlem CH, Myers M, Goldstick J, et al. Factors associated with naloxone availability and dispensing through Michigan’s pharmacy standing order. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2022;48(4):454–463. doi:

- 49. Beiting KJ, Molony J, Ari M, Thompson K. Targeted virtual opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution in overdose hotspots for older adults during COVID-19. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2022;70(11):E26-E29. doi:

- 50. Chatterjee A, Yan S, Xuan Z, et al. Broadening access to naloxone: community predictors of standing order naloxone distribution in Massachusetts. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;230:109190. doi:

- 51. Abouk R, Pacula RL, Powell D. Association Between state laws facilitating pharmacy distribution of naloxone and risk of fatal overdose. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(6):805–811. doi:

- 52. Akers JL, Hansen RN, Oftebro RD. Implementing take-home naloxone in an urban community pharmacy. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S161-S167. doi:

- 53. Bennett AS, Bell A, Doe-Simkins M, Elliott L, Pouget E, Davis C. From peers to lay bystanders: findings from a decade of naloxone distribution in Pittsburgh, PA. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2018;50(3):240–246. doi:

- 54. Brown M, Tran C, Dadiomov D. Lowering barriers to naloxone access through a student-led harm reduction program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2023;63(1):349–355. doi:

- 55. Clark AK, Wilder CM, Winstanley EL. A systematic review of community opioid overdose prevention and naloxone distribution programs. J Addict Med. 2014;8(3):153–163. doi:

- 56. Dadiomov D, Bolshakova M, Mikhaeilyan M, Trotzky-Sirr R. Buprenorphine and naloxone access in pharmacies within high overdose areas of Los Angeles during the COVID-19 pandemic. Harm Reduct J. 2022;19(1):69. doi:

- 57. Duska M, Goodman D. Implementation of a prenatal naloxone distribution program to decrease maternal mortality from opioid overdose. Matern Child Health J. 2022;26(5):985–993. doi:

- 58. Eswaran V, Allen KC, Bottari DC, et al. Take-home naloxone program implementation: lessons learned from seven Chicago-Area Hospitals. Ann Emerg Med. 2020;76(3):318–327. doi:

- 59. Gangal NS, Hincapie AL, Jandarov R, Frede SM, Boone JM, Heaton PC. Physician-approved protocols increase naloxone dispensing rates. J Addict Med. 2022;16(3):317–323. doi:

- 60. Gruver BR, Jiroutek MR, Kelly KE. Naloxone coprescription in U.S. ambulatory care centers and emergency departments. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2020;60(5):e44–e49. doi:

- 61. Hill LG, Holleran Steiker LK, Mazin L, Kinzly ML. Implementation of a collaborative model for opioid overdose prevention on campus. J Am Coll Health. 2020;68(3):223–226. doi:

- 62. Katzman JG, Takeda MY, Greenberg N, et al. Association of take-home naloxone and opioid overdose reversals performed by patients in an opioid treatment program. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(2):e200117. doi:

- 63. Kilaru AS, Liu M, Gupta R, et al. Naloxone prescriptions following emergency department encounters for opioid use disorder, overdose, or withdrawal. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;47:154–157. doi:

- 64. LeSaint KT, Montoy JCC, Silverman EC, et al. Implementation of a leave-behind naloxone program in San Francisco: a one-year experience. West J Emerg Med. 2022;23(6):952–957. doi:

- 65. Lewis DA, Park JN, Vail L, Sine M, Welsh C, Sherman SG. Evaluation of the overdose education and naloxone distribution program of the Baltimore student harm reduction coalition. Am J Public Health. 2016;106(7):1243–1246. doi:

- 66. Acharya M, Chopra D, Hayes CJ, Teeter B, Martin BC. Cost-effectiveness of intranasal naloxone distribution to high-risk prescription opioid users. Value Health. 2020;23(4):451–460. doi:

- 67. Cherrier N, Kearon J, Tetreault R, Garasia S, Guindon E. Community distribution of naloxone: a systematic review of economic evaluations. Pharmacoecon Open. 2022;6(3):329–342. doi:

- 68. Nguyen TT, Applewhite D, Cheung F, Jacob S, Mitchell E. Implementation of a multidisciplinary inpatient opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution program at a large academic medical center. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2022;79(24):2253–2260. doi:

- 69. Oliva EM, Christopher MLD, Wells D, et al. Opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution: Development of the Veterans Health Administration’s national program. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2017;57(2S):S168-S179 e4. doi:

- 70. Patel SV, Wenger LD, Kral AH, et al. Optimizing naloxone distribution to prevent opioid overdose fatalities: results from piloting the Systems Analysis and Improvement Approach within syringe service programs. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):278. doi:

- 71. Smart R, Pardo B, Davis CS. Systematic review of the emerging literature on the effectiveness of naloxone access laws in the United States. Addiction. 2021;116(1):6–17. doi:

- 72. Riazi F, Toribio W, Irani E, et al. Community case study of naloxone distribution by hospital-based harm reduction program for people who use drugs in New York city. Front Sociol. 2021;6:619683. doi:

- 73. Rife T, Tat C, Jones J, Pennington DL. An initiative to increase opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution for homeless veterans residing in contracted housing facilities. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2021;34(1):188–195. doi:

- 74. Spelman JF, Peglow S, Schwartz AR, Burgo-Black L, McNamara K, Becker WC. Group visits for overdose education and naloxone distribution in primary care: a pilot quality improvement initiative. Pain Med. 2017;18(12):2325–2330. doi:

- 75. Szydlowski EMP, Caruana SSP. Telephone-based opioid overdose education and naloxone distribution (OEND) pharmacy consult clinic. Subst Abus. 2018;39(2):145–151. doi:

- 76. Wenger LD, Showalter D, Lambdin B, et al. Overdose education and naloxone distribution in the San Francisco County Jail. J Correct Health Care. 2019;25(4):394–404. doi:

- 77. Watson A, Guay K, Ribis D. Assessing the impact of clinical pharmacists on naloxone coprescribing in the primary care setting. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(7):568–573. doi:

- 78. Wilkerson DM, Groves BK, Mehta BH. Implementation of a naloxone dispensing program in a grocery store-based community pharmacy. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2020;77(7):511–514. doi:

- 79. D. M. Trump declares opioid epidemic a national public health emergency. Accessed April 1, 2024. https://www.cnn.com/2017/10/26/politics/donald-trump-opioid-epidemic/index.html

- 80. Cid A, Daskalakis G, Grindrod K, Beazely MA. What is known about community pharmacy-based take-home naloxone programs and program interventions? A scoping review. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(1):30. doi:

- 81. McClellan C, Lambdin BH, Ali MM, et al. Opioid-overdose laws association with opioid use and overdose mortality. Addict Behav. 2018;86:90–95. doi:

- 82. Haffajee RL, Cherney S, Smart R. Legal requirements and recommendations to prescribe naloxone. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2020;209:107896. doi:

- 83. Sohn M, Delcher C, Talbert JC, et al. The impact of naloxone coprescribing mandates on opioid-involved overdose deaths. Am J Prev Med. 2023;64(4):483–491. doi:

- 84. Ali SA, Shell J, Harris R, Bedder M. Naloxone prescriptions among patients with a substance use disorder and a positive fentanyl urine drug screen presenting to the emergency department. Harm Reduct J. 2023;20(1):144. doi:

- 85. Zang X, Walley AY, Chatterjee A, et al. Changes to opioid overdose deaths and community naloxone access among Black, Hispanic and White people from 2016 to 2021 with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: an interrupted time-series analysis in Massachusetts, USA. Addiction. 2023;118(12):2413–2423. doi:

- 86. Gomes T, Ledlie S, Tadrous M, Mamdani M, Paterson JM, Juurlink DN. Trends in opioid toxicity-related deaths in the US before and after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, 2011-2021. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2322303. doi:

- 87. Samuels E. Emergency department naloxone distribution: a Rhode Island department of health, recovery community, and emergency department partnership to reduce opioid overdose deaths. R I Med J (2013). 2014;97(10):38–39.

- 88. Guy GP Jr, Haegerich TM, Evans ME, Losby JL, Young R, Jones CM. Vital Signs: Pharmacy-based naloxone dispensing—United States, 2012-2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(31):679–686. doi:

- 89. Binswanger IA, Koester S, Mueller SR, Gardner EM, Goddard K, Glanz JM. Overdose education and naloxone for patients prescribed opioids in primary care: a qualitative study of primary care staff. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12): 1837–1844. doi:

- 90. Evoy KE, Hill LG, Davis CS. Considering the potential benefits of over-the-counter naloxone. Integr Pharm Res Pract. 2021;10:13–21. doi:

- 91. Salvador JG, Sussman AL, Takeda MY, Katzman WG, Moya Balasch M, Katzman JG. Barriers to and recommendations for take-home naloxone distribution: perspectives from opioid treatment programs in New Mexico. Harm Reduct J. 2020;17(1):31. doi:

- 92. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. United States dispensing rate maps. 2023. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/data-research/facts-stats/us-dispensing-rate-maps.html

- 93. Meyerson BE, Moehling TJ, Agley JD, Coles HB, Phillips J. Insufficient Access: Naloxone Availability to laypeople in Arizona and Indiana, 2018. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2021;32(2):819–829. doi:

- 94. Hamilton L, Davis CS, Kravitz-Wirtz N, Ponicki W, Cerda M. Good Samaritan laws and overdose mortality in the United States in the fentanyl era. Int J Drug Policy. 2021;97:103294. doi:

- 95. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Drug overdose deaths rise, diparities widen. 2022. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/overdose-death-disparities/index.html

- 96. Martignetti L, Sun W. Perspectives of stakeholders of equitable access to community naloxone programs: a literature review. Cureus. 2022;14(1):e21461. doi:

- 97. Zhu DT, Tamang S, Humphreys K. Promises and perils of the FDA’s over-the-counter naloxone reclassification. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2023;23:100518. doi:

- 98. Tse WC, Sanfilippo P, Lam T, Dietze P, Nielsen S. Community pharmacy naloxone supply, before and after rescheduling as an over-the-counter drug: sales and prescriptions data, 2014-2018. Med J Aust. 2020;212(7):314–320. doi: