Introduction

Patient blood management (PBM) is defined as the timely application of evidence-based medical and surgical concepts designed to maintain haemoglobin (Hb) concentration, optimise haemostasis, and minimise blood loss in an effort to improve patient outcome []. The concept of PBM consists of 3 main pillars, namely, maximising red blood cell (RBC) mass (pillar 1), minimization and control of blood loss (pillar 2) and tolerating anaemia, and maximising physiological reserves to maximise oxygen availability and delivery (pillar 3) [, ]. So far, >100 individual PBM measures have been defined based on the broad interdisciplinary fields and temporal application []. Recent publications revealed that implementation of PBM reduces morbidity, mortality, and the use of allogeneic RBC transfusions [-]. Particularly, preoperative anaemia management, the first pillar of a holistic PBM program, has shown to increase Hb levels in patients undergoing surgery [, -].

In the past years, surveys on PBM practice and knowledge have been conducted [-]. A survey at 11 secondary and tertiary hospitals revealed that knowledge and implementation of PBM remain extremely variable across hospitals. The prevalence of preoperative anaemia management ranged from 0.0 to 40.0%, and measures to minimize iatrogenic blood loss (e.g., use of cell salvage) differed significantly between hospitals []. According to a study by Manzini et al. [], the heterogeneity of organization of preoperative anaemia management mainly refers to the availability of national guidelines, waiting times for elective surgery, and laboratory parameters for anaemia diagnosis. A subsequent survey in 2019 by the PBM in Europe (PaBloE) working group at 7 European university hospitals participating in a “European Blood Alliance” project on preoperative anaemia management revealed poor knowledge about PBM. Here, 24.0% of the clinicians were unaware of the association between preoperative anaemia and increased morbidity and mortality. Also, 29.0% of the participants stated that they had no sufficient knowledge on preoperative anaemia treatment [].

As presented before, data on efficacy and knowledge of PBM are variable. In order to elucidate the increase in awareness towards perioperative anaemia, patient’s blood resource, and transfusion from a physician’s perspective, a questionnaire was sent to 56 hospitals participating in the German PBM Network.

Materials and Methods

The survey was conducted within the German PBM Network. The network was founded in 2014 and represents a collaboration of hospitals of any size. It was founded to offer support to hospitals aiming to implement a PBM program in order to increase patient safety. The survey questions were constructed by the author team, and included 28 questions addressing the following topics: (1) demographic data of the participants (age, gender, levels of care of hospital, and medical discipline) and general questions on local PBM program (length of implementation, guidelines, everyday contact, number of PBM measures), (2) preoperative anaemia management, (3) minimization and control of blood loss, and (4) rational use of allogenic blood products. Anaemia was defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) as Hb concentration of <12 g/dL in women and <13 g/dL for men. Since the questionnaire was conducted in German, we translated the questions to English for the purposes of this paper (shown in online suppl. Table 1; see http://www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000517607 for all online suppl. material).

The questionnaire was adapted for use in UmfrageOnline website (https://www.umfrageonline.de). Access to the survey together with a cover letter was sent by email to every local PBM coordinator. All hospitals (n = 56) are part of the German PBM Network group, which was founded in 2014. The PBM coordinator was asked to distribute the survey at their hospital. Physicians from any medical discipline were invited to participate. The survey started on October 27th and was closed on December 19th. On November 24th, a reminder calling for participation was sent to the local PBM coordinator. The survey participation was voluntary. Conclusions about the hospital or the participant were not possible. The majority of questions (n = 14) had either predetermined potential answers to choose from or an additional field listed as “other” for participants to put their own responses. Two of the 28 questions were open (age and waiting time [days] for elective surgery), and participants were able to insert their own responses. The increase in awareness was defined as gained knowledge and understanding of the participants through implemented PBM measures towards the effect and increase of patient safety. To assess the physician’s subjective increase in awareness, numeric rating scales from 0 (no increase) to 10 (maximum increase) were used (n = 12 questions). To assess the number of implemented PBM measures, predetermined answers (1–10, 11–20, ≥21 PBM measures) were used to cover the most important measures of all 3 PBM pillars.

Statistical Analysis

The responses were transferred to Microsoft Excel (Excel 365; Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Descriptive statistical methods mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range (25%/75%) were used to analyse data. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality of continuous variables. Normally distributed data were compared with Student’s t-test. Non-normally distributed data were compared with the Mann-Whitney U test. Categorical variables were compared with the χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test. For group comparisons, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used. Statistical analysis and graphical illustration were performed using SigmaPlot® (Systat Software GmbH, Erkrath, Germany) and SPSS® software (SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 21.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Characteristics of Physicians

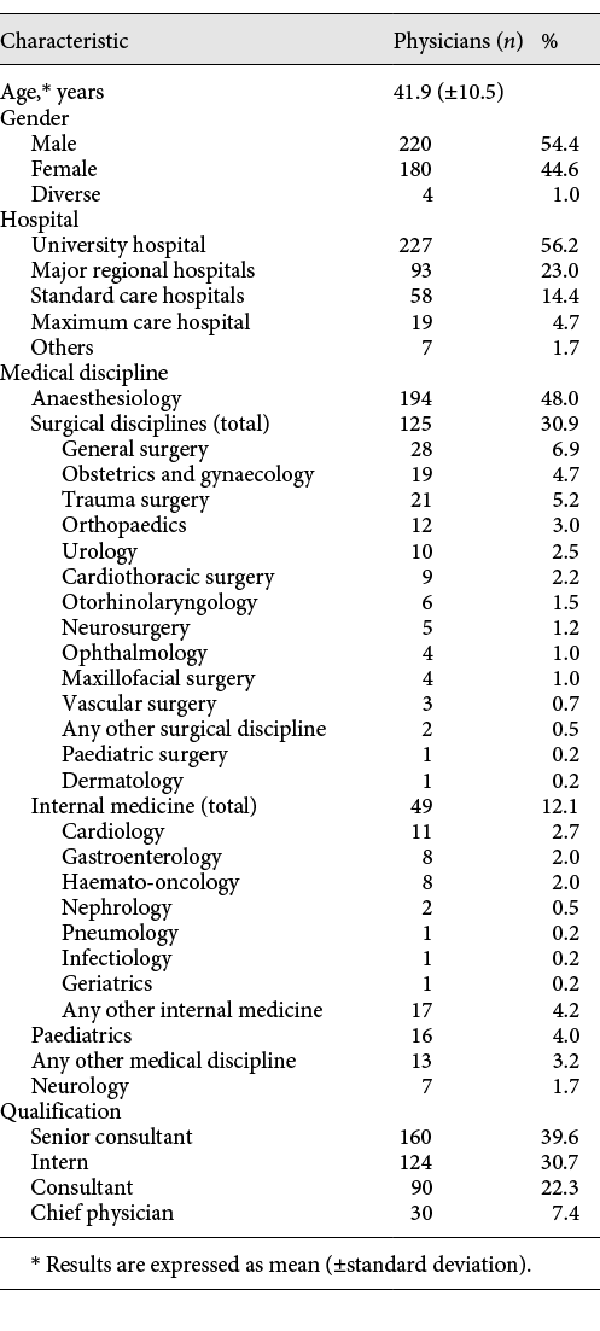

In total, 578 physicians responded to the questionnaire. Of these, 174 (30.1%) did not complete the questionnaire and were excluded from further analysis. In total, 404 (69.9%) physicians completed the survey and were included in final analysis. Overall, 227 (56.2%) specified working at a university hospital, 93 (23.0%) in major regional hospitals, 58 (14.4%) in standard care hospitals, 19 (4.7%) in maximum care hospitals, and 7 (1.7%) in other hospitals (e.g., specialised orthopaedic clinics). The majority of responding physicians were anaesthetists (n = 194; 48.0%), followed by surgeons (n = 125; 30.9%) and internal medicine specialists (n = 49; 12.1%). Further characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Organization of PBM

All hospitals were part of the German PBM Network group. The time of implemented PBM programs at the physician’s hospitals ranged between 1 and 15 years. The mean time of PBM program existence was 4.8 (±2.2) years. In total, 357 (88.4%) of the physicians reported of local guidelines on PBM at their hospitals, 13 (3.2%) stated that they had no local guideline, and 34 (8.1%) did not provide detailed information on existence of guidelines. Regarding the number of implemented PBM measures at the hospitals, 80 (19.8%) participants reported the implementation of 1–10 PBM measures, 48 (11.9%) of 11–20 PBM measures, and 63 (15.6%) of ≥21 implemented PBM measures. In total, 213 (52.7%) stated they could not provide detailed knowledge about implemented PBM measures.

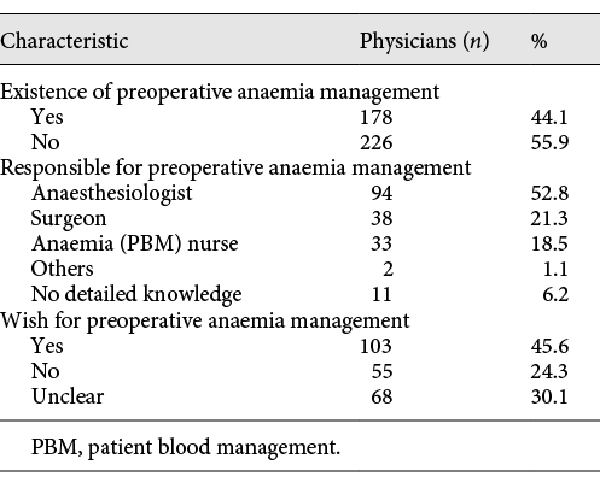

If preoperative anaemia management was carried out in the hospital (n = 178; 44.1%), anaesthetists were mostly responsible (n = 94; 52.8%), followed by surgeons (n = 38; 21.3%), or an anaemia nurse (n = 33; 18.5%). Patients contacted for preoperative anaemia management ranged between 1 and 90 days (6.0 [±8.3]). In case hospitals did not conduct preoperative anaemia management (n = 226; 55.9%), of these 103 (45.6%) wished for implementation of preoperative anaemia management (shown in Table 2).

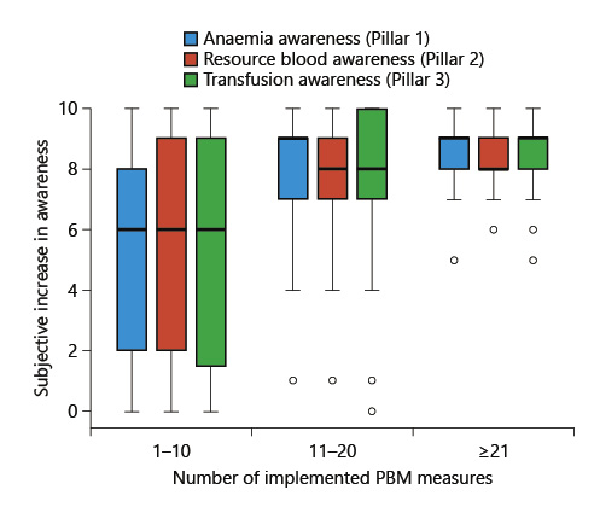

Physician’s Subjective Increase in Awareness towards Anaemia, Patient’s Blood resource, and Transfusion by Number of Implemented PBM Measures

The physician’s subjective increase in awareness towards anaemia was rated the highest by physicians from hospitals with ≥21 implemented PBM measures, compared to physicians from hospitals with 11–20 PBM measures and 1–10 PBM measures (8.2 [±2.0] vs. 7.8 [±2.4] vs. 5.3 [±3.6]), respectively. The subjective increase in awareness was significantly higher in physicians from hospitals with ≥21 PBM measures (p < 0.001) and 11–20 PBM measures (p < 0.001) compared to 1–10 implemented PBM measures.

Similar results were obtained for the physician’s subjective increase in awareness towards patient’s blood resource. Subjective increase was rated 7.6 (±2.5) by physicians from hospitals with ≥21 PBM measures, 7.5 (±2.7) by 11–20 PBM measures, and 5.7 (±3.7) by 1–10 PBM measures. The subjective increase in awareness towards patient’s blood resource was also significantly higher in physicians from hospitals with ≥21 PBM measures (p = 0.009) and 11–20 PBM measures (p = 0.014) than those with 1–10 implemented PBM measures.

The subjective increase in awareness towards transfusion was rated 8.1 (±1.9), 7.7 (±2.4), and 5.6 (±3.7) by physicians from hospitals with ≥21, 11–20, and 1–10 implemented PBM measures, respectively. The subjective increase in transfusion awareness was significantly higher in physicians from hospitals with ≥21 PBM measures (p < 0.001) and 11–20 PBM measures (p = 0.022) than those with 1–10 implemented PBM measures (shown in Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

Physician’s subjective increase in awareness by the hospital’s number of implemented PBM measures. Box and Whisker plot of the physician’s subjective increase in awareness (0 [no increase] – 10 [maximum increase]). Comparison was performed with the Kruskal-Wallis test. The horizontal lines represent median values (perioperative anaemia): p < 0.001 for comparing 1–10 versus 11–20 PBM measures; p < 0.001 for comparing 1–10 versus ≥21 PBM measures (patient’s blood resource): p = 0.014 for comparing 1–10 versus 11–20 PBM measures; p = 0.009 for comparing 1–10 versus ≥21 PBM measures (transfusion): p = 0.022 for comparing 1–10 versus 11–20 PBM measures; p < 0.001 for comparing 1–10 versus ≥21 PBM measures. PBM, patient blood management.

In case of existing preoperative anaemia management, physicians reported a significantly higher subjective increase in awareness towards anaemia than physicians without implemented preoperative anaemia management (6.9 [±3.2] vs. 5.1 [±3.8]; p < 0.001).

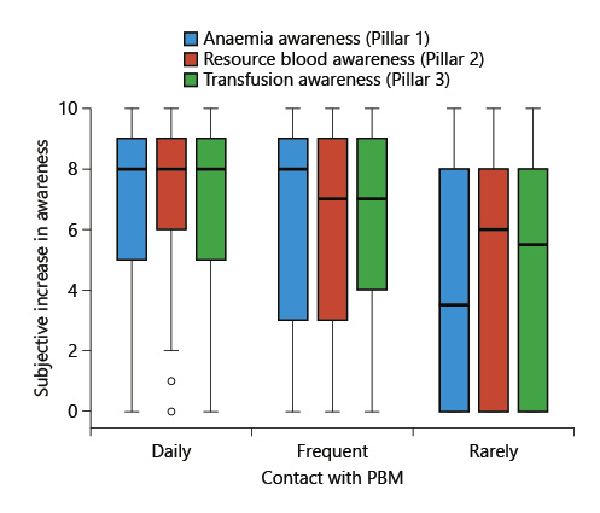

Physician’s Subjective Increase in Awareness towards Anaemia, Patient’s Blood Resource, and Transfusion by Frequency of PBM Contact

The physician’s subjective increase in awareness towards anaemia was rated the highest by physicians with daily PBM contact compared to physicians with frequent (≥1/week) or rare (<1/week) PBM contact (6.6 [±3.3] vs. 5.9 [±3.6] vs. 4.1 [±3.9]), respectively. The subjective increase in anaemia awareness was significantly higher in physicians with daily PBM contact than in those with frequent (p < 0.001) and rare PBM contact (p < 0.001).

A subjective increase in physician’s awareness towards patient’s blood resource was also higher in physicians with daily contact than in physicians with frequent and rare PBM contact (7.0 [±3.3] vs. 5.9 [±3.5] vs. 4.7 [±3.9]), respectively. The subjective increase was significantly higher in physicians with daily PBM contact than in those with frequent (p = 0.09) and rare PBM contact (p < 0.001).

The subjective increase in awareness towards transfusion was rated 6.6 (±3.4), 6.1 (±3.5), and 4.7 (±3.9) by physicians with daily, frequent, and rare PBM contact, respectively. The subjective increase in awareness was significantly higher in physicians with daily PBM contact than in those with rare PBM contact (p < 0.001). In addition, the subjective increase differed significantly between frequent and rare PBM contact (p = 0.012) (shown in Fig. 2).

Fig. 2

Physician’s subjective increase in awareness by the physician’s frequency of PBM contact. Box and Whisker plot of the physician’s subjective increase in awareness (0 [no increase] – 10 [maximum increase]). Comparison was performed with the Kruskal-Wallis test. The horizontal lines represent median values. Frequent PBM contact: ≥1/week; rare PBM contact: <1/week. Blue (perioperative anaemia): p < 0.001 for comparing daily versus frequent; p < 0.001 for comparing daily versus rarely; red (patient’s blood resource): p < 0.001 for comparing daily versus rarely; p = 0.009 for comparing daily versus frequent; p = 0.047 for comparing frequent versus rarely; green (transfusion): p < 0.001 for comparing daily versus rarely; p = 0.012 for comparing frequent versus rarely. PBM, patient blood management.

Discussion

We utilised an online survey to assess physician’s subjective increase in awareness regarding perioperative anaemia, patient’s blood resource, and transfusion after the implementation of PBM. Our results revealed that the subjective increase in awareness was rated higher as more PBM measures were implemented at the participating physician’s hospital. In addition, the subjective increase was higher in physicians with daily PBM contact than those with frequent and rare PBM contact.

In the past years, PBM has proven to be effective and is increasingly incorporated into standard patient care. In 2010, the WHO urged member states to implement and promote PBM in clinical practice []. So far, several hospitals have successfully implemented PBM programs [, ]. In our study, the majority of the participants (88.4%) reported the use of local PBM guidelines at their hospitals. Same results were demonstrated by a recent study among ten European hospitals by the PaBloE working group, where local guidelines were in place in 7 of ten hospitals (70.0%) []. Regarding the number of implemented PBM measures, most participants (19.8%) reported of 1–10 implemented PBM measures, followed by ≥21 PBM measures (15.6%) and 11–20 PBM measures (11.9%). Considering the fact that 52.7% of the participants stated they could not provide detailed knowledge of the number of implemented PBM measures emphasizes the need for education as part of a holistic PBM program. Stressing the importance of education, a study by Abelow et al. [] conducted in 2014 at a tertiary hospital describes the effect of an intervention including educational presentations to physicians and computerized alerts on RBC utilization, recommending RBC transfusion at Hb <8 g/dL in symptomatic patients. One year later, the percentage of RBC transfusion at Hb ≥8 g/dL was reduced by 18.8% (p < 0.001) []. In 2020, authors showed that the simple educational intervention a few years prior, possibly contributed to sustained improvement in the appropriateness of RBC transfusions. There was a continuous reduction in the percentage of RBC transfusions at an Hb level ≥8 g/dL over the following 3 years []. Meybohm et al. [] states that educational activities regarding PBM should occur initially and regularly, at least annually, and should be endorsed by public and medical authorities. Furthermore, learning materials should be easily accessible, for example, via websites, guidelines, posters, or education materials []. The support of knowledge on PBM and education on evidence-based transfusion practice may also help reduce the use of allogeneic RBCs as well as health-care costs []. In the curriculum of some hospitals, education of PBM and transfusion medicine in young physicians has already been implemented [].

The results of subjective increase in awareness towards perioperative anaemia, patient’s blood resource, and transfusion among physicians demonstrate that changes were the highest in physicians from hospitals with ≥21 implemented PBM measures and in physicians with daily PBM contact. A comprehensive PBM program includes >100 different measures, divided into 4 clinical bundle blocks, namely, management of patient’s anaemia (block 1), optimization of coagulation (block 2), interdisciplinary blood conservation modalities (block 3), and optimal use of allogeneic blood (block 4). Preoperative anaemia management is a widely applied and highly effective PBM measure. Management of patient’s anaemia includes diagnosis of anaemia (e.g., blood count, ferritin, and transferrin saturation) and treatment of anaemia by administration of intravenous iron, vitamin B12, folic acid, or erythropoietin []. Supplementation of intravenous iron in case of preoperative anaemia has shown to be effective in improving Hb levels, reducing intraoperative RBC transfusion rates and hospital length of stay [].

Regarding blood conversation strategies, a meta-analysis based on 47 trials revealed that cell salvage is efficacious in reducing the overall need for allogeneic RBC transfusion in surgical patients by 39% []. Furthermore, the use of tranexamic acid, the use of limited number of swabs for blood absorption or reduced size of blood collection tubes, and restrictive frequency of the blood test are PBM measures to decrease intraoperative and postoperative iatrogenic blood loss []. Our results emphasize that PBM, as a practical concept, increases its clinical and personal efficacy the more it is applied and the more measures it contains. These 2 observations are mutually dependent on each other: 49.0% of the anaesthetist had contact with PBM daily compared to surgeons (24.0%) and physicians from any other medical speciality (35.3%). As perioperative physicians, anaesthesiologists are commonly confronted with the management of perioperative anaemia, blood loss and transfusion before, during, and after surgery []. In our study, anaesthesiologists were the majority of participating physicians (48.0%). Even though a variety of medical disciplines are included, this distribution of physician’s medical specialities might result in responder bias. It is noteworthy that data varied across the participants. Reasons might be the variety of affiliated hospitals to the German PBM Network regarding the hospital size and membership period. Therefore, the number of implemented PBM measures and daily contact with PBM strategies varied across the participants. The same results of variety were demonstrated by another survey on the implementation of a trauma system with 17 predefined trauma system criteria in Norway. Here, the authors state that the number of fulfilled criteria also correlated strongly with the size of the hospital and the frequency of trauma activation [].

Limitations

Our study has some limitations such as the selection of participants and hospitals. With all hospitals being part of the German PBM Network group, contact with preoperative anaemia management, strategies to reduce blood loss, and restrictive transfusion strategy are higher than physicians from other hospitals without PBM involvement. This may result in selection bias. In addition, as multiple participants have come from the same institution, we cannot exclude that some outcomes are clustered and represent institutional, rather than individual, changes. For future surveys, the specific description of implemented PBM measures at the participant’s hospital should be considered. This information may support the implementation of a new and sustainable PBM program at the reader’s hospitals. It is noteworthy that the German PBM Network contains a large variety of hospitals. Therefore, the number of implemented PBM measures varies among the 56 participating institutions, depending on the hospital’s size and period of membership.

In addition, our study includes a wide variation of medical disciplines with a large number of participants. However, most participants represent the anaesthesiology and surgical department. Based on the fact that this was an online survey that was sent to the according PBM coordinator, the response rate to this survey is not estimable. Furthermore, the evaluation of the physician’s subjective changes refers to a perioperative setting. In our study, 30.1% of the physicians did not complete the questionnaire. The highest dropout rate (14.2%) was found in questions on preoperative anaemia management. As 55.9% of the physicians stated that preoperative anaemia management was not conducted at their hospital, inability to answer the questions regarding this topic might have lowered motivation to proceed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings indicate that the physician’s awareness towards perioperative anaemia, patient’s blood resource, and transfusion has increased. The higher the subjective increase in awareness, the more PBM measures are implemented at the physician’s hospital and the more frequent is the clinical PBM contact. To further increase awareness regarding all 3 PBM pillars, local PBM practices need to expand regarding the number of implemented PBM measures as this results in a more frequent PBM contact in everyday clinical practice.

Appendix

The German PBM Network group: Hannah von der Ahe; Tim Allendörfer; Petra Auler; Stephanie Backes; Olaf Baumhove; Alexandra Bayer; Matthias Boschin; Ole Broch; Stephan Czerner; Tim Drescher; Bernhard Dörr; Gerd Engers; Hermann Ensinger; Andreas Farnschläder; Jens Faßl; Patrick Friederich; Jens Friedrich; Andreas Greinacher; André Gottschalk; Kristina Graf; Kerstin Große Wortmann; Oliver Grottke; Matthias Grünewald; Raphael Gukasjan; Martin Gutjahr; Karlheinz Gürtler; A. Himmel; Christian Hofstetter; Gabriele Kramer; Thomas Martel; Jan Mersmann; Matthias Meyer; Max Müller; Michael Müller; Diana Narita; Ansger Raadts; Christoph Raspé; Beate Rothe; Anke Sauerteig; Timo Seyfried; Astrid Schmack; Axel Schmucker; Klaus Schwendner; Andrea Steinbicker; Josef Thoma; Wolfgang Tichy; Oliver Vogt; Henry Weigt; Johanna Weiland; Manuel Wenk; Maieli Wenz; Thomas Wiederrecht; Christoph Wiesenack; Marc Winetzhammer; Michael Winterhalter and Maria Wittmann.

Acknowledgment

The German PBM Network group was founded 2014 in Germany.

Statement of Ethics

The study presented includes an online survey on a voluntary basis and did not involve human subjects. Therefore, approval of the Local Ethics Committee of the Goethe University Hospital (chairman Dr. J. Hätscher) was not necessary. The present study was conducted ethically in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflict of Interest Statement

P.M. and K.Z. received grants from B. Braun Melsungen, CSL Behring, Fresenius Kabi, and Vifor Pharma for the implementation of Frankfurt’s PBM program and honoraria for scientific lectures from B. Braun Melsungen, Vifor Pharma, Ferring, CSL Behring, and Pharmacosmos. F.P. received honoraria from Pharmacosmos for scientific lectures. F.J.R. received grants from HemoSonics LLC and honoraria for scientific lectures from Keller Medical GmbH. All other authors declare no competing interests.

Funding Sources

This research received departmental funding only.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: V.N., P.M., F.P., and F.J.R. Acquisition of the data: V.N. and F.J.R. Analysis and interpretation of data: V.N., F.P., and F.J.R. Drafting or revising the manuscript: V.N., F.P., S.C., P.H., K.Z., P.M., and F.J.R. Final approval of the version to be submitted: V.N., F.P., S.C., P.H., K.Z., P.M., and F.J.R.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material files (http://www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000517607). Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. (SABM) SftAoBM. Available from: https://sabm.org/who-we-are/.

- 2. Goodnough LT, Shander A. Patient blood management. Anesthesiology. 2012;116(6):1367–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e318254d1a3.

- 3. Shander A, Isbister J, Gombotz H. Patient blood management: the global view. Transfusion. 2016;56(Suppl 1):S94–102. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/trf.13529.

- 4. Meybohm P, Richards T, Isbister J, Hofmann A, Shander A, Goodnough LT, et al. Patient blood management bundles to facilitate implementation. Transfus Med Rev. 2017;31(1):62–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tmrv.2016.05.012.

- 5. Althoff FC, Neb H, Herrmann E, Trentino KM, Vernich L, Füllenbach C, et al. Multimodal patient blood management program based on a three-pillar strategy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(5):794–804. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000003095.

- 6. Triphaus C, Judd L, Glaser P, Goehring MH, Schmitt E, Westphal S, et al. Effectiveness of preoperative iron supplementation in major surgical patients with iron deficiency: a Prospective Observational Study. Ann Surg. 2019.

- 7. Theusinger OM, Stein P, Spahn DR. Applying “patient blood management” in the trauma center. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2014;27(2):225–32. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0000000000000041.

- 8. Keding V, Zacharowski K, Bechstein WO, Meybohm P, Schnitzbauer AA. Patient blood management improves outcome in oncologic surgery. World J Surg Oncol. 2018;16:159. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12957-018-1456-9.

- 9. Meybohm P, Herrmann E, Steinbicker AU, Wittmann M, Gruenewald M, Fischer D, et al. Patient blood management is associated with a substantial reduction of red blood cell utilization and safe for patient’s outcome: a Prospective, Multicenter Cohort Study with a noninferiority design. Ann Surg. 2016;264(2):203–11. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001747.

- 10. Froessler B, Palm P, Weber I, Hodyl NA, Singh R, Murphy EM. The important role for intravenous iron in perioperative patient blood management in major abdominal surgery: a Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Surg. 2016;264(1):41–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0000000000001646.

- 11. Ionescu A, Sharma A, Kundnani NR, Mihăilescu A, David VL, Bedreag O, et al. Intravenous iron infusion as an alternative to minimize blood transfusion in peri-operative patients. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):18403. http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-75535-2.

- 12. Muñoz M, Acheson AG, Auerbach M, Besser M, Habler O, Kehlet H, et al. International consensus statement on the peri-operative management of anaemia and iron deficiency. Anaesthesia. 2017;72(2):233–47. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/anae.13773.

- 13. Van der Linden P, Hardy JF. Implementation of patient blood management remains extremely variable in Europe and Canada: the NATA benchmark project: an observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2016;33(12):913–21. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/EJA.0000000000000519.

- 14. Manzini PM, Dall’Omo AM, D’Antico S, Valfrè A, Pendry K, Wikman A, et al. Patient blood management knowledge and practice among clinicians from seven European university hospitals: a multicentre survey. Vox Sang. 2018;113(1):60–71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/vox.12599.

- 15. Jung-König M, Füllenbach C, Murphy MF, Manzini P, Laspina S, Pendry K, et al. Programmes for the management of preoperative anaemia: audit in ten European hospitals within the PaBloE (Patient Blood Management in Europe) Working Group. Vox Sang. 2020;115(3):182–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/vox.12872.

- 16. World Health Organization. Availability, safety and quality of blood products: resolution. 2010. Available from: https://www.who.int/bloodsafety/resolutions/en/.

- 17. Fischer DP, Zacharowski KD, Müller MM, Geisen C, Seifried E, Müller H, et al. Patient blood management implementation strategies and their effect on physicians’ risk perception, clinical knowledge and perioperative practice: the frankfurt experience. Transfus Med Hemother. 2015;42(2):91–7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000380868.

- 18. Mehra T, Seifert B, Bravo-Reiter S, Wanner G, Dutkowski P, Holubec T, et al. Implementation of a patient blood management monitoring and feedback program significantly reduces transfusions and costs. Transfusion. 2015;55(12):2807–15. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/trf.13260.

- 19. Abelow A, Gafter-Gvili A, Tadmor B, Lahav M, Shepshelovich D. Educational interventions encouraging appropriate use of blood transfusions. Vox Sang. 2017;112(2):150–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/vox.12493.

- 20. Pasvolsky O, Shepshelovich D, Berger T, Tadmor B, Shochat T, Raanani P, et al. Extended follow-up of an educational intervention encouraging appropriate use of blood transfusions. Acta Haematol. 2019;143:446–51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1159/000503988.

- 21. Zuckerberg GS, Scott AV, Wasey JO, Wick EC, Pawlik TM, Ness PM, et al. Efficacy of education followed by computerized provider order entry with clinician decision support to reduce red blood cell utilization. Transfusion. 2015;55(7):1628–36. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/trf.13003.

- 22. Lin Y, Tinmouth A, Mallick R, Haspel RL. Investigators ftB-T. BEST-TEST2: assessment of hematology trainee knowledge of transfusion medicine. Transfusion. 2016;56(2):304–10.

- 23. Meybohm P, Choorapoikayil S, Wessels A, Herrmann E, Zacharowski K, Spahn DR. Washed cell salvage in surgical patients: a review and meta-analysis of prospective randomized trials under PRISMA. Medicine. 2016;95(31):e4490. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000004490.

- 24. Divatia J. Blood transfusion in anaesthesia and critical care: Less is more!Indian J Anaesth. 2014;58(5):511–4. http://dx.doi.org/10.4103/0019-5049.144641.

- 25. Dehli T, Gaarder T, Christensen BJ, Vinjevoll OP, Wisborg T. Implementation of a trauma system in Norway: a national survey. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2015;59(3):384–91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/aas.12467.