Identity is defined as an individual’s sense of self based on interpersonal characteristics, social roles, and breadth of affiliations including ethnicity (). Intersectionality is the interface between a person’s identities in relation to inequalities in social systems. It was developed by law professor ) to delineate how society bestows differential experiences of privilege and discrimination on people based upon their combination of personal, social, and political identities. These inequities require societal level interventions such as changing laws, policies, and practices to rectify.

Intersectionality has generated much interest in psychology for understanding societal concerns () such as discrimination (), health care disparities (), adverse childhood experiences (), and stigma-related stress (). It has also been applied to professional psychology to ensure culturally informed services to diverse individuals (). In contrast, the application of intersectionality has yet to be established in the field of clinical neuropsychology. This absence is illustrated by the number of articles identified by PubMed searches pairing intersectionality with psychology (650) versus neuropsychology (3).

There are several possible reasons why intersectionality principles have not been incorporated within clinical neuropsychology. First, identities appear more relevant to clinical or counseling psychology which focus on personality make-up and treating emotional disorders versus clinical neuropsychology which focuses on brain functioning and cognition. Similarly, concepts of discrimination and privilege appear less relevant to brain science and cognitive functioning. Third, the target of clinical neuropsychology is the individual with assessment and cognitive rehabilitation as the primary services provided. This is in contrast to intersectionality which focuses on groups of people and society as the target for intervention. Fourth, most of the pertinent literature on institutional discrimination is outside the strict purview of clinical neuropsychology and published in nonneuropsychological journals. Thus, neuropsychologists may not be aware of how intersectionality relates to neuropsychology unless actively sought out.

Last, but perhaps most important, is that the environment has largely been ignored in neuropsychological conceptualization of brain organization and functioning. Current models of brain functioning that are foundational to neuropsychological training, such as cerebral laterality, dorsal and ventral streams, automatic and controlled processing, and executive functioning (for a review see ), focus on information processing and decision-making for adapting to and controlling the environment. In these models of brain functioning, the environment is a passive recipient versus a reciprocal influencer. The lone exception is cognitive reserve theory which states that education and enriched experiences can enhance cognitive reserve in the brain, thus is protective against symptoms caused by neuropathology ().

The current omission of intersectionality in neuropsychology is unfortunate as it is argued that these concepts can enhance our understanding of the brain and improve our interventions. For example, the premise that the environment is an active agent in an individual’s experience is consistent with the current neuroscience literature on brain organization and development (), much which has yet to be widely disseminated into current models of brain conceptualization. Intersectionality provides a unique perspective for appreciating lower performances on Western tests by many minoritized groups of people. It can also assist in understanding heterogeneity among groups of people, particularly those who share the same ethnicity. Finally, intersectionality identifies targets and strategies for intervention that can improve cognitive functioning for patients who experience societal discrimination.

This article describes how intersectionality principles are germane to and imperative for moving the discipline of clinical neuropsychology forward. A key concept is that society is an active agent in influencing the development, organization, and assessment of brain functioning. Institutional discrimination contributes to disparities not only in cognitive functioning on Western-based tests but also in accessing neuropsychological services for minoritized groups of people. First, an overview of cultural neuroscience will be introduced to provide a foundation for how the environment can impact brain organization and functioning. This literature establishes a foundation for the next section describing how institutional discrimination impacts experiences that are influential for brain development and cognitive functioning. This is followed by a description of institutional biases that impact accessibility to neuropsychological evaluations and culturally valid assessments for minoritized groups. Finally, recommendations for incorporating intersectionality into clinical neuropsychology are discussed. In this article, people of European origin will be referred to as Whites as opposed to Caucasians, the latter being a socially constructed category based on physical appearances that has been used to discriminate against groups of people and maintain social hierarchies ().

Impact of the Environment on Brain Organization and Functioning

Cultural neuroscience is an interdisciplinary field of study bridging theories from anthropology, cultural psychology, neurosciences, neurogenetics, and population genetics. It examines the mutual influence of culture on genetics and functional brain organization and these neurobiological processes on culture across the lifespan, intergenerationally, and across evolutionary timescales ().

The leading theory in cultural neuroscience is the culture-gene co-evolutionary theory which posits that adaptive behavior is based on the interaction of two complementary process: cultural and evolutionary selection (; ). Cultural traits are adaptive behaviors developed to address environmental and ecological challenges under which genetic selection occurs. Traits will vary with geographical region and social environments (). Conversely, niche construction states that humans can influence selected traits by creating or altering the environment resulting in a continuous cycle of mutual influence (). Thus, a primary goal of cultural neuroscience research is identifying specific cultural and genetic traits that support adaptive behaviors and mold psychological and neural architectures ().

An example is the co-evolution of the cultural value of collectivism with the serotonin transporter gene (SLC6A4) to produce adaptive behaviors (). Theoretically, collectivist values are more likely to develop in nations facing environmental pressures such as a long history of pathogen exposure resulting in infectious diseases. In these countries, an increased preference for group members and reduced contact with persons outside the group would be a good strategy to reduce the potential transmission of diseases (). This hypothesis was supported by ) who found that people from collectivist nations in geographic regions with an increased prevalence of infectious diseases are more like to carry the short (S) versus long (L) allele of serotonin transporter gene 5HTTLPR associated with lower levels of anxiety and mood disorders. Thus, collectivism serves an antipathogen function, while genetic selection associated with this cultural value serves and antipsychopathologic function.

Interactions between the individual and environment are modulated by epigenetic processes which alter gene expression without modifying the DNA sequence (). The DNA sequences of base pairs house about 25,000 genes which are the blueprint for specific traits of each individual. Genes are expressed when base pair sequences are transcribed into a strand of RNA which is then translated into a protein (). Epigenetic modifications to gene expression are regulated by writers and erasers which are enzymes that can add or remove epigenetic marks. Readers then consolidate these changes by binding these modifications, thus altering the expression of the gene (). The sum total of all epigenetic alterations is known as the epigenome ().

Specific epigenetic mechanisms include the following: DNA methylation involves the bonding of a methyl group to a DNA molecule. This process renders the gene inaccessible for transcription. Histone protein modifications entails changes to the histone protein’s central globular domain or N-terminal tail which can either activate or repress gene transcription. Non-coding RNAs (ncRNA), which make up 98% of DNA, do not code for proteins but instead perform other functions akin to glia cells in the central nervous system. Non-coding RNA mechanisms impact processes that can either repress or positively regulate gene expression. Location of chromatin within the nucleus can impact gene expression. Chromatin in proximity to the lamina lining the inside of nuclear envelope generally represses gene transcription, whereas chromatin located away from the lamina is associated with gene activation ().

Epigenetic modifications can be triggered by negative environmental exposures such as toxins () or stress and trauma (), diet (), and other substances ingested by the individual such as alcohol () or addictive drugs (), and behaviors engaged in such as physical exercise (). Epigenetic changes can have profound influence on brain organization and functioning, impacting neuronal development, neuroplasticity, cognition, and behavior (). For example, synaptic plasticity, or sustained changes in the synaptic strength between neurons, is regulated by DNA methylation which influences the transcription of genes coding for proteins reelin (Reln) and activity-regulated cytoskeletal. These proteins modulate synaptic function and plasticity (for a review see ). The impact of epigenetic processes can be long lasting, persisting for decades () or transmitted across generations (; for a review on epigenetics see ).

An example of how experience impacts epigenetic processes is the association between lifetime stress with accelerated aging in elderly urban African–Americans (). Stress responses are associated with the release of glucocorticoids which exerts action on glucocorticoid receptors (GR) that are located throughout the body. Activation of the GR binds homodimer to glucocorticoid response elements (GRE) in the regulatory regions of genes, which are responsible for inducing persistent changes in DNA methylation. In African–Americans experiencing chronic stress, local demethylation changes are found in Cytosine-phosphate-Guanosine sites (CpGs) that are in proximity of a GRE. This site-specific pattern of demethylation has been implicated in aging-related phenotypes and increased risk for developing diseases of aging including coronary artery disease, arteriosclerosis, and leukemias ().

In summary, current theories and research provide growing support that the environment influences brain organization, functioning, and cognition. The brain is malleable through epigenetic processes that provide a mechanism for the environment to impact brain organization within one’s lifetime with the potential to influence brain organization of progeny.

Intersectionality adds the context of society for understanding the impact of the environment on cognition. Intersectionality principles would indicate that societies have social hierarchies based upon the characteristics, identities, or behaviors of its people. Societies will develop policies and institutional structures to ensure advantages or privileges to prioritized groups and disadvantages to nonprioritized minoritized groups. Furthermore, these institutional structures will perpetuate advantages to persons of privilege to maintain societal hierarchies (). In the next section, examples of how society discriminates against minoritized groups in brain development will be discussed.

Institutional Biases for Brain Development and Organization

Education

One of the strongest findings in the literature is the impact of quantity and quality of education on neuropsychological test performances (; ; ; ; ; ). Neuroimaging studies report a positive impact of years of education on cortical volume (), with the most consistent findings in the frontal areas (; ), although positive findings were also found in the temporal lobes (). Results from a functional MRI study () reported positive education effects on frontal, cingulate, and right parietal areas on an N-back task. Given the impact of education on cognition, practices or polices that place groups of people at a disadvantage for receiving a good education should impact the cognitive development of these people.

In the United States, educational disparities, including lower achievement at all grade levels, a higher drop-out rate, and lower enrollment in and completion of post-secondary education, exist between Whites and most minoritized ethnic groups including Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, and some Asian–Americans such as Bhutanese and Laotian Americans (; , ). A number of factors are purported to mediate these discrepancies. First is the lack of access to a quality and appropriate education for minoritized populations. For example, students from immigrant households generally attend schools with inadequate language resources and teachers who have limited experience and training for working with English language learners (). These students are disadvantaged as a teacher’s years of experience and quality of training, and a bilingual education is correlated with children’s academic achievement (; ). Limited bilingual education resources have differential impact upon immigrant groups as English proficiency vary between groups. For example, immigrants from Mexico have among the lowest rates of English proficiency (34%), while English proficiency is higher for immigrants from East and Southeast Asians (50%), South American (56%), and Sub-Saharan Africa (74%) (). Similarly, reservation schools also lack qualified teachers, appropriate language and cultural curriculums, and access to technology, and the facilities tend to be in extreme states of disrepair (). High poverty areas with predominantly Black and Hispanic students are less likely to offer college-prep courses and prerequisite math and science courses required for college level classes ().

Another disadvantage is that school environments for many minoritized students are typically located in high poverty neighborhoods which are not conducive learning environments. Classes are overcrowded. Immigrant students who are segregated by ethnicity and language are more likely to feel unsafe and fear being harmed or attacked by gangs within the school (). Black children face numerous biases that can impact academic performance such as lower expectations for achievement and lower rates of placement in gifted classes (). They are also punished and suspended at higher rates for similar infractions in comparison to White counterparts. Moreover, suspensions are predictive of lower grades in subsequent years ().

A significant factor in the disadvantaged educational experiences of minoritized students is discriminatory practices in school funding. Nationwide, schools with high percentages of minoritized children receive less per pupil than predominantly White districts even when controlling for socioeconomic status (SES). For example, one study reported that poor White school districts receive about $150 less per pupil in relation to the national average; however, this is still nearly $1,500 more per pupil in poor non-White school districts (). Moreover, funding disparities are trending higher with the increase in racial segregation in schools (). Educational funding is foundational for academic achievement as sustained increases in school spending have been associated with higher rates of high school graduation and enrollment in college (). Thus, not only are minoritized students disadvantaged for receiving a quality education, this disparity may be widening if current trends of increased segregation in schooling continue.

Economics

Poverty is associated with a myriad of cascading and interacting factors that can negatively impact brain development in children (). Neuroimaging studies on children who come from low SES households report reduced cortical surface area, thickness, and overall volume primarily in frontal and temporal areas associated with attention, language acquisition, executive functioning, memory, and emotional regulation (). Decrements in these structures have accounted for 15–20% of academic deficits (), and SES has been demonstrated to account for 60% more variance in academic achievement versus genome-wide polygenic scores ().

There are two proposed paths in which poverty can impact brain organization and development. First, is limited cognitive or social stimulation such as less parental time engaged in reading to children (), attendance in lower resourced schools (), and limited access to the internet (). Second, is chronic exposure to chaotic environments, deviant behaviors, or violence (; ) and unhealthy living situations including exposure to toxins (), air and noise pollutions, and overcrowding (). Thus, it is not surprising that neighborhood poverty impacts child brain development incrementally above family income (). One proposed mechanism is that chaotic environments result in a weaker connectivity between the mesial frontal cortex and the amygdala (). Reduced frontal controls over emotional processing of fear and detection of threats is associated with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology ().

A second but related mechanism is the development of cognitive strategies that are adaptive to living in chaotic environments but are ill suited for functioning in mainstream society. According to , children who live in unpredictable environments must adapt by developing fast intuitive decision-making strategies (fast strategists) in order to react swiftly to potential threats. In contrast, for children who grow up in stable environments, a slower deliberate, a future-oriented decision-making strategy allowing for long range planning (slow strategists) would be more adaptive. This adaptation model has been supported by research conducted on children and families in the United States () and China (). Unfortunately, the skills of children with fast cognitive strategies such as tracking changes in the immediate environment or shifting attention between tasks (; ; ) are not recognized or valued in Western educational systems. Instead, our current educational system is geared toward slow strategist cognitive styles where academic success is based on performances on standardized tests that do not measure the unique skills of fast strategists. Thus, it is not surprising that children who employ fast strategist problem-solving styles are disadvantaged in the current educational system and demonstrate lower achievement ().

Most minoritized groups including: Native Americans (25.4%) (), Blacks (19.5%), Hispanics (17.0%), and most Asian–Americans (e.g., Mongolian 25%, Burmese 25%, Bangladeshi 19%, Nepalese 17%, Pakistani 15%) have higher poverty rates than Whites 8.2% (; ). Relatedly, the wealth, or accumulated monetary resources, of minoritized groups are also much less than for Whites. For example, the wealth of the median Black family is $3,600 or 2% of the wealth of the median White family $147,000, while the assets of the median Hispanic family is $6,660 or 4% of White families ().

There are numerous factors contributing to these economic discrepancies. First is educational attainment which is associated with both earnings and unemployment rate: college graduates earn an average $69,358/year with a 3.5% unemployment rate, high school graduates earn a mean of $42,068/year with a 6.2% unemployment rate, while the average person with less than high school diploma earns $32,552/year, with an unemployment rate of 8.3% (). As described in the previous section, most minoritized groups have lower educational attainment than Whites with numerous factors contributing to this discrepancy. Another factor for lower postsecondary educational attainment is economics. The high and rising costs of a college education are prohibitive for many Blacks and Hispanics (), while Hispanics are more likely to opt for work to support families after high school versus continuing their education ().

However, economic inequities cannot be solely attributed to differences in educational attainment as not only do Whites earn more than Blacks and Hispanics at similar levels of education, their wealth accumulation with increased educational attainment is also higher (). Wage disparities for equal educational attainment are most pronounced when comparing minoritized women with White males. For example, with a college degree Black and Hispanic women earn about 65% of White males (). In addition, despite increases in educational attainment, in comparison to Whites, Blacks and Native Americans have lower rates of upward mobility and higher rates of downward mobility leading to persistent intergenerational economic disparities (). Thus, other societal discriminatory factors are contributory. For example, Federal Government funding sources are less likely to award grants to Black innovators and entrepreneurs (). Blacks are less likely to put money into retirement accounts and are less likely to enjoy home ownership due to systemic discriminatory housing and mortgage practices. This results in fewer tax advantages and gains in real estate and the stock market (). Moreover, once purchased, Black owned real estate is worth less than comparable White homes due to racialized appraisal practices (). White progeny are also more likely to receive inheritances and receive larger inheritances than Blacks which perpetuates wealth disparities across generations ().

There are also discriminatory practices in the criminal justice system. Data from New York indicated that Blacks and Hispanics are overrepresented in the prison system. Blacks constitute 13% of the general population and 30% of the prison population, while the numbers for Hispanics are 18% and 22%, respectively. Blacks and Hispanics are more likely to be arrested for similar drug offences than Whites, more likely to be detained, offered higher bail rates, less likely to make bail, and their sentences are more likely to involve incarceration. The ramification of incarceration not only includes perpetuating the cycle of poverty by impacting future employment opportunities but also perpetuates the existence of discriminatory laws as former convicts lose the right to vote, hence, political voice. In addition, because voter registration is one of the primary sources for recruiting jurors, incarceration reduces the eligible pool of Black and Hispanic jurors who are typically the first to be eliminated by prosecuting attorneys ().

Health Disparities

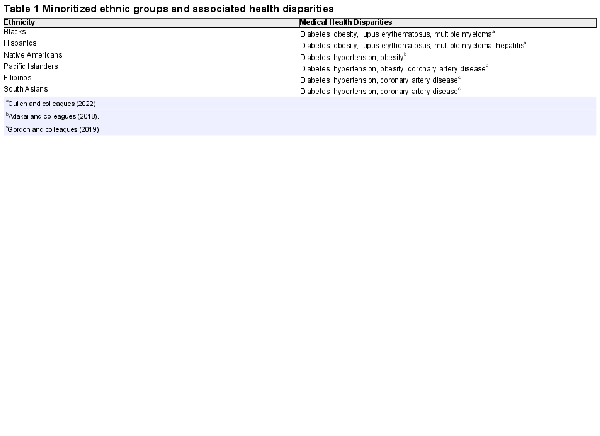

Health and health care disparities exist between Whites and minoritized ethnic groups including Blacks, Hispanics (), Native Americans (), Pacific Islander, Filipinos, and South Asians (). Many of these medical disparities are associated with increased risk for developing neurological diseases. Specific disorders for the aforementioned ethnic groups are presented in Table 1. Older sexual minority adults also demonstrate health disparities with higher rates of disability, poor mental health, smoking, and excessive drinking than heterosexual counterparts ().

There is a growing body of literature indicating that institutional racism is a significant contributor to health care disparities and reduced health service utilization among minoritized groups. Perceived discrimination has been associated with medical conditions such as coronary artery disease, increased body mass index, psychiatric diseases and symptoms including depression, anxiety, and poor sleep, risky health behaviors including alcohol and tobacco use (for a review see ), and overall poorer mental and physical functioning (). Perceived discrimination can also impact treatment by increasing mistrust of health care providers, dissatisfaction with care, delays in seeking care, and treatment nonadherence ().

Although findings are mixed, the weight of studies suggests several neurobiological responses moderate the relationship between perceived discrimination and cardiovascular disease which is a significant risk factor for vascular neurocognitive disorders. For example, discriminatory treatment is associated with dysregulation of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Adrenal (HPA) axis which mediates the stress response by releasing the hormone cortisol in the bloodstream to mobilize physiological resources to potential threats. Sustained cortisol release is associated with coronary artery calcification and cardiovascular mortality (; ). Perceived discrimination can trigger the immune system response involving the release of proinflammatory cytokines which are protein messengers that coordinate the inflammatory process. Chronic inflammatory processes are associated with atherosclerosis (). Discrimination increases spontaneous activity in the amygdala, which is associated with affective processing including fear, vigilance, and threat detection (), and functional connectivity between the amygdala and multiple neural regions. The strongest connections are with the thalamus which is associated with early processing of sensory information (). Amygdalar activity has been associated with arterial inflammation and risk for cardiovascular disease events (; for a review see ).

Given these pathways to cardiovascular disease, it is not surprising that recent studies have demonstrated that the chronic experience of discrimination is neurotoxic and associated with cognitive deficits. In a nationally representative cohort of Black adults aged 51 and older, discrimination was associated with both depressive symptoms and vascular disease, both mediating the effects of discrimination on cognition. Depression negatively impacted performances on episodic memory, executive functioning, memory, language, and visual construction, while vascular disease mediated performances on executive functioning and visuoconstruction. Discrimination was associated with negative performances on executive functioning and visuoconstruction (). In a sample of community dwelling older Black adults, lifetime racial discrimination was associated with lower hippocampal volumes, while everyday discrimination was associated with a faster longitudinal development of white matter (). Similar processes associated with chronic discrimination are purported to mediate cognitive decline in sexual minority elders ().

Accessibility to Healthcare Services

There are institutional biases in what populations receive priority for receiving neuropsychological assessments and treatment. For example, it is estimated that the prevalence of women who have sustained a traumatic brain injury (TBI) secondary to intimate partner violence (IPV) is 11–12 times the number of persons sustaining TBI from military personnel and athletes combined (). Despite the large discrepancy in numbers, professional athletes receive priority for identifying TBI over women in abusive relationships. Every NFL player is mandated to undergo baseline cognitive testing each season as part of their concussion protocol for treatment. The reported average number of players who sustained concussions during the 2015–2021 seasons is 13% per season (; ). In contrast, prevalence data for TBI secondary to IPV range from 17% to 100% based on data from women seeking emergency medical services or institutional assistance for IPV (for a review see ). The findings are highly variable and the data are limited as there is no systematic data collection process (). Similar to clinical data, TBI secondary to IPV receives much less attention than TBI for athletes in research. Advance searches with keywords traumatic brain injury football (TBIF) versus traumatic brain injury intimate partner violence (TBIIPV) in major neuropsychology journals yielded the following number of articles: Clinical Neuropsychologist TBIF-56, TBIIPV-9, Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology TBIF-127, TBIIPV-4. Moreover, for both journals, TBIIPV articles were often conference abstracts versus full articles. TBI secondary to IPV has been labeled an “invisible” epidemic as it is more prevalent in women with disadvantaged identities such as those living in poverty and rural areas, and women from minoritized backgrounds including Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, and Asian–Americans who immigrated by marrying non-Asian men (for a review see ).

Minoritized groups experience numerous barriers to procuring medical services. For example, many Hispanics who are non-citizens work in low paying jobs and do not qualify for medical insurance. Thus, Hispanics have one of highest rates of uninsured (30%) among ethnic groups (). They also may lack medical leave or choose to work versus taking sick days to seek treatment for sick children and are less likely to own their own car or have a driver’s license, the latter due to poor English literacy or illegal residence status. In addition, language barriers may exist for first-generation Hispanics who require Spanish speaking medical providers, as well as assistance for negotiating Medicaid eligibility criteria. Language issues would be especially pronounced in regions with smaller Hispanic populations ().

Reluctance to seek treatment due to fear and mistrust of medical professionals is another significant issue for many minoritized groups. Unauthorized immigrants may fear being deported when interacting with institutions or persons outside one’s network (). Transgender individuals may avoid seeking medical treatment as they may anticipate disrespectful and insensitive treatment based upon past experiences. Experiences of mistreatment are exacerbated by intersecting gender, minority status, poverty, and rurality (). Many Native Americans receive health care from Indian Health Services which are severely and chronically underfunded with per capita expenditures are 2.5 times lower than the general public (). Lack of trust of health care providers and high turnover rates are reasons for not seeking health care for elders who typically have significant medical needs ().

Culturally Informed Neuropsychological Services

Institutional biases exist for minoritized patients to receive neuropsychological services that are culturally informed, hence more appropriate and valid for that individual. In a survey of United States and Canadian neuropsychologists, practitioners reported a lack of appropriate multicultural training for working with ethnic minority patients with some performing assessments in foreign languages despite limited proficiency. In addition, there is a paucity of neuropsychologists from minoritized groups who would be more familiar with patients from their culture and speak or be familiar with their language (). Data from the American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology, National Association of Neuropsychology, and Society for Clinical Neuropsychology 2020 Practice and Salary Survey () estimate that only 13.4% of clinical neuropsychologists are from an ethnic minority background. This is significantly lower than the 42% identified in the U.S. Census with the following breakdown: Blacks (2% neuropsychology, 13% U.S. population), Hispanics (4.5% neuropsychology, 18.5% U.S. population), and Asian–Americans (4.6% neuropsychology, 5.9% U.S. population). Although the number of Asian–American neuropsychologists approach the general population, service disparities still exist for a significant number of Asian–American patients, as there are 21+ specific ethnicities listed in the U.S. Census with most speaking a unique language or languages, two thirds are foreign born thus may require linguistic capabilities, and the vast majority live on the coasts and in metropolitan areas (). Thus, access issues exist for specific ethnicities (e.g., Bhutanese) and those living in rural locations.

There are a number of institutional biases contributing to the disparities in minoritized neuropsychologists. A significant issue is economics. The increasing cost of postsecondary education requires many minoritized students to work during school and after completing their undergraduate degree. Implications include: reduced time for studying, which in combination with poorer academic preparation in primary and secondary school, can impact grade point average and performance on the Graduate Records Examination (GRE), less time for research experiences, and less time to meet other undergraduate requirements needed for graduate study in neuropsychology. The lack of minority faculty role models and research opportunities may also make graduate education in neuropsychology less appealing for minoritized students (). Additional obstacles to success exist for minoritized students if accepted into graduate programs or hired as faculty in academic institutions. A lack of role models, mentors, or sponsors that are readily accessible to White counterparts can result in naivete to the inherent knowledge of unwritten rules of academia. Other barriers include the experience of micro- and macro-aggressions, bullying, feelings of isolation, biases in evaluations, less opportunities for funding and awards, and biases in the peer-review process ().

Minoritized faculty are also routinely asked to participate in extra, uncompensated diversity related duties such as serving on committees addressing diversity curriculum or recruitment or serving on dissertation committees for minoritized students, often in areas outside of one’s expertise, These demands, referred to as “cultural tax,” are expected to be accomplished on top of one’s existing workload. Thus, it takes away time and energy from generating research which is the primary basis for tenure and promotions ().

Even if cultural and linguistic appropriate services are available to minoritized patients, biases still exist in the neuropsychological assessment process. When asked about the biggest challenge for providing neuropsychological assessments for culturally different patients, most neuropsychologists, including those from the United States, Canada, Europe, and Australia, cite the lack of translated tests and appropriate norms (; ; ). The fairness or cross-cultural validity of the tests or neuropsychological assessment process itself is not questioned. Thus, the implicit assumption is that neuropsychological tests are objective measures that can be applied to all cultures with proper translations and norms.

This is an erroneous assumption. In her research with Zinacantan girls in Chiapas Mexico, Greenfield (1997) found that basic processes involved in testing, such as asking questions about things that are not present or expectations of knowledge being contained within each individual versus the entire group, did not apply to these people. It was concluded that psychological assessment is a Western technology that is fraught with the values and biases of Western culture, thus may be biased for test takers from nonwestern cultures. This finding is supported by the robust literature on the negative impact of culture on neuropsychological test performance (; ; ; ; ), as well as differential performances by Kenyan and Alaskan Native children on tests measuring indigenous versus western conceptions of intelligence (; ).

Perhaps more foundational, our understanding of brain processes is also impacted by institutional biases. The overwhelming majority of behavioral science research is conducted on Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic (WEIRD) samples. They account for 12% of the world’s population, yet 96% of peer-reviewed behavioral sciences and 99% of developmental neuroscience studies are conducted on these samples (; ). This biased sampling is problematic as WEIRD persons are highly unrepresentative of the world. For example, the United States is a high-income country (), predominantly White (76.3%) (), monolingual (78%) (), with a relatively high level of education among the general population (13.4 years) (). In contrast, most countries are considered middle or low-income economies (high 80, middle 107, low 31) (), are non-White (82.8% of world’s population live outside of Europe and North America) (), and speak more than one language (60%; 43% bilingual, 13% trilingual, 4% multilingual) (), with much lower levels of education attainment (9th grade or lower, 54%) while (6th grade education or lower 25%) ().

Thus, it should not be surprising that studies have found differences between Westerners and other cultures on aspects of memory, attention, visual perception, categorization, and spatial cognition (for a review see ). For example, in contrast to Westerners who tend to focus on distinct objects, Easterners demonstrate a holistic processing bias for perception and memory, thus employ different brain structures on cognitive tasks in comparison to Westerners (for a review see ). Hence, our current knowledge of brain–behavior relationship is limited, incomplete, or inaccurate (; ). An implication of the Western sampling biases is that neuroscience theories and knowledge may not apply to people from non-Western countries; however, may be perceived to be universal and perpetuated as future studies are conducted on the same skewed sampling as past studies which this knowledge is initially based upon.

In addition to sampling, there are also biases in the focus of published research. For example, report that even when studies examine disparities on minoritized populations, most do not examine mechanisms of mental-health disparities including existing frameworks such as the biopsychosocial model of racism and minority stress model. Without assessing stressors unique to minoritized groups, the default is to attribute differences to genetic factors and shared family environments. Perhaps most concerning, is that these biases occur in top tier psychology journals which are the most highly cited thus would be expected to publish articles examining the latest theories and findings in the literature.

Recommendations for Infusing Intersectionality into Clinical Neuropsychology

In summary, intersectionality has yet to be infused into the consciousness of clinical neuropsychology, this despite the growing neuroscience literature demonstrating the significant impact the environment has on brain development and organization. This paper posits that the environment of society is an active agent in bestowing privileges and disadvantages to groups of people which has significant ramifications for cognition. It describes numerous ways that institutional biases contribute to educational, economic, health, and healthcare disparities for minoritized groups, all of which have been associated with the integrity of the brain and cognition. Of particularly interest is the growing support for the negative impact of perceived discrimination. This factor has not been examined in the majority of studies evaluating for cognition in minoritized groups. Equally pertinent to the discipline is that institutional biases also contribute to disparities in the access to culturally informed and linguistically appropriate neuropsychological assessments. Underrepresentation of practicing minoritized clinical neuropsychologists, inherent biases in the assessment process, and biases in scientific knowledge that are predominantly based upon skewed Western samples that do not match the demographics of most of the world’s population contribute to these inequities. It should be emphasized that without institutional change, disparities for minoritized groups may persist indefinitely.

Given the potential ubiquitous impact the environment and society has on minoritized patients, the discipline of clinical neuropsychology must acknowledge and incorporate intersectionality into its practice. It is argued that ignoring intersectionality principles would violate all of Psychology’s General Ethical Principles: Beneficence and Nonmaleficence or efforts to “benefit” and “do no harm” to our patients, Fidelity and Responsibility which refers to “professional and scientific responsibilities” to our patients and to society, Integrity which entails promoting “accuracy, honesty, and truthfulness” in neuropsychological practice and research, Justice in ensuring that all person have access to and benefit from our services which are equal in quality while maintaining an awareness of potential biases and limitations in our expertise to avoid unjust practices, and Respect for People’s Rights and Dignity through an awareness and acceptance of individual differences while striving to eliminate biases of these factors in our work ().

The following are recommendations to incorporate intersectionality into the discipline and practice of clinical neuropsychology:

Neuropsychologist should be aware of the cultural neuroscience and intersectionality literature that is pertinent to the discipline. This literature should be part of the foundational knowledge for neuropsychological training curriculums and competencies for all neuropsychologists. As this literature is often beyond the immediate purview of clinical neuropsychology, continuing education should be routinely offered at conferences or virtual webinars. Addressing intersectionality in continuing education presentations should be a requirement or strongly encouraged. Intersectionality should also be incorporated into the board certification process.

To facilitate equal access of culturally informed and linguistically appropriate services, graduate education and clinical training programs should bolster the recruitment and training of minoritized students and increase the number of faculty from minoritized groups. Specific recommendations to increase admissions include: limiting the importance of current indicators of merit (e.g., GPA, GREs, publications) while adopting a more holistic selection process that assesses clinical aptitude through life experiences and other considerations such as bilingualism that are less biased by SES, increasing the participation of faculty from minoritized in the selection process, and avoiding selection processes that require minoritized applicants to conform to societal norms of the majority group ().

Neuropsychologists should be aware of cultural biases in the neuropsychological assessment process and develop skills in providing culturally informed and linguistically appropriate evaluations. They should be knowledgeable of the culture of their patients (for a review see ), and American Education Research Association (AERA), American Psychological Association (APA), and the National Council on Measurement in Education (NCME) standards for fairness in testing () develop contextualized cultural conceptualization skills, for example, by using the ECLECTIC Framework (, ), to guide the assessment process by maximizing fairness according to AERA standards, and develop clinical skills in working with minoritized patients () including working with interpreters (). The impact of institutional discrimination on the patient’s cognition, performance on Western tests, and everyday functioning should be incorporated in the case conceptualization and recommendations. For example, making recommendations to enhance coping for microaggressions or racism (for example, see ) may be effective interventions for developing healthy coping skills that can limit the impact of discrimination for developing cardiovascular disease.

Research should not only be more inclusive of minoritized participants but also examine how disparities associated with institutional discrimination can impact their experiences, brain organization and development, and performance on Western tests. Developing and evaluating the effectiveness of interventions targeting institutional discrimination would be another direction. The impact of perceived discrimination on the brain or strengths-based educational techniques for fast strategist learners would be examples of research topics.

Neuropsychologists should engage in advocacy to address institutional discrimination against minoritized groups. Facilitating national standards for screening TBI secondary to IPV, supporting initiatives to improve educational opportunities for minoritized students, or engaging in community participatory research to improve health services for minoritized patients are examples of projects that neuropsychologists can contribute their expertise.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Adakai M., Sandoval-Rosario M., Xu F., Aseret-Manygoats T., Allison M., Greenlund K. J., et al (2018). Health disparities among American Indians/Alaska Natives—Arizona, 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 67, 1314–1318. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6747a4.

- Adams L. M., Miller A. B. (2021). Mechanisms of mental-health disparities among minoritized groups: How well are the top journals in clinical psychology representing this work?Clinical Psychological Science, 10, 387–416.

- Aguilar C., Karyadi K. A., Kinney D. I., Nitch S. R. (2017). The use of RBANS among inpatient forensic monolingual Spanish speakers. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 32, 437–449.

- Akin Y. (2020). The time tax put on scientists of colour. Nature, 583(7816), 479–481.

- Allen D., Wolniak G. C. (2019). Exploring the effects of tuition increases on racial/ethnic diversity at public colleges and universities. Research in Higher Education, 60, 18–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-018-9502-6.

- American Education Research Association, American Psychological Association, and the National Council on Measurement in Education (2014). Standards for educational and psychological testing (2nd ed.). Washington DC: American Education Research Association.

- American Psychological Association (2017). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct, (pp. 1–16). Washington DC: American Psychological Association.

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Inclusive language guidelines. Retrieved August 8, 2022, fromhttps://www.apa.org/about/apa/equity-diversity-inclusion/language-guidelines.pdf.

- American Psychological Association, Presidential Task Force on Educational Disparities. (2012). Ethnic and racial disparities in education: Psychology’s contributions to understanding and reducing disparities. Retrieved fromhttp://www.apa.org/ed/resources/racial-disparities.aspx.

- Andreotti C., Hawkins K. A. (2015). RBANS norms based on the relationship of age, gender, education, and WRAT-3 reading to performance within an older African American sample. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29, 442–465.

- Arentoft A., Byrd D., Monzones J., Coulehan K., Fuentes A., Rosario A., et al (2015). Socioeconomic status and neuropsychological functioning: Associations in an ethnically diverse HIV+ cohort. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 29, 232–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2015.1029974.

- Asante-Muhammad D., Kamra E., Sanchez C., Ramirez K., Tec R. (2022). Racial wealth snapshot: Native Americans. Retrieved June 6, 2022, fromhttps://ncrc.org/racial-wealth-snapshot-native-americans/.

- Babenko O., Kovalchuk I., Metz G. A. S. (2015). Stress-induced perinatal and transgenerational epigenetic programming of brain development and mental health. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 48, 70–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.11.013.

- Barch D., Pagliaccio D., Belden A., Harms M. P., Gaffrey M., Sylvester C. M., et al (2016). Effect of hippocampal and amygdala connectivity on the relationship between preschool poverty and school age depression. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 173, 625–634. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15081014.

- Bartrés-Faz D., González-Escamilla G., Vaqué-Alcázar L., Abellaneda-Pérez K., Valls-Pedret C., Ros E., et al (2019). Characterizing the molecular architecture of cortical regions associated with high educational attainment in older individuals. Journal of Neuroscience, 39, 4566–4575.

- Berhe A. A., Barnes R. T., Hastings M. G., Mattheis A., Schneider B., Williams B. M., et al (2022). Scientists from historically excluded groups face a hostile obstacle course. Nature Geoscience, 15, 2–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41561-021-00868-0.

- Bhutta N., Chang A., Dettling L., Hsu J. (2020). Disparities in wealth by race and ethnicity in the 2019 survey of consumer finances. Retrieved June 22, 2022, fromhttps://www.federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/disparities-in-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-in-the-2019-survey-of-consumer-finances-20200928.htm.

- Boller B., Mellah S., Ducharme-Laliberté G., Belleville S. (2017). Relationships between years of education, regional grey matter volumes, and working memory-related brain activity in healthy older adults. Brain Imaging and Behavior, 11, 304–317.

- Boone K. B., Victor T. L., Wen J., Razani J., Pontón M. (2007). The association between neuropsychological scores and ethnicity, language, and acculturation variables in a large patient population. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22, 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2007.01.010.

- Boyd R., Richerson P. J. (1985). Culture and the evolutionary process. Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

- Bradley R. H., Corwyn R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233.

- Budiman A. (2020). Key findings about U.S. immigrants. Retrieved June 12, 2022, fromhttps://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/

- Budiman A., Ruiz N. (2021). Key facts about Asian origin groups in the U.S.Retrieved June 5, 2022, fromhttps://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2021/04/29/key-facts-about-asian-origin-groups-in-the-u-s/.

- Butler A. A., Webb W. M., Lubin F. D. (2016). Regulatory RNAs and control of epigenetic mechanisms: Expectations for cognition and cognitive dysfunction. Epigenomics, 8, 135–151. https://doi.org/10.2217/epi.15.79.

- Camera L. (2019). White students get more K-12 funding than students of color: Reporthttps://www.usnews.com/news/education-news/articles/2019-02-26/white-students-get-more-k-12-funding-than-students-of-color-report

- Cavalli-Sforza L., Feldman M. (1981). Cultural transmission and evolution: A Quantitative approach. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Cha A., Cohen R. (2019). Reasons for being uninsured among adults aged 18–64 in the United States, 2019. Washington DC: National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved June 15, 2022, fromhttps://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db382-H.pdf.

- Chetty R., Hendren N., Jones M. R., Porter S. R. (2020). Race and economic opportunity in the United States: An intergenerational perspective. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 135, 711–783. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjz042.

- Chiao J. Y. (2009). Cultural neuroscience: A once and future discipline. Progress in Brain Research, 178, 287–304. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17821-4.

- Chiao J. Y., Blizinsky K. D. (2010). Culture-gene coevolution of individualism-collectivism and the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR). Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 277(1681), 529–537. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.1650.

- Chiao J. Y., Cheon B. K. (2010). The weirdest brains in the world. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 88–90. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X10000282.

- Chiao J. Y., Cheon B. K., Pornpattananangkul N., Mrazek A. J., Blizinsky K. D. (2013). Cultural neuroscience: Progress and promise. Psychological Inquiry, 24, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840X.2013.752715.

- Clark U., Miller E., Hegde R. (2018). Experiences of discrimination are associated with greater resting amygdala activity and functional connectivity. Biological Psychiatry Cognition, Neuroscience, and Neuroimaging, 3, 367–378. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2017.11.011.

- Clauss-Ehlers C. S., Chiriboga D. A., Hunter S. J., Roysircar G., Tummala-Narra P. (2019). APA multicultural guidelines executive summary: Ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality. American Psychologist, 74, 232–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000382.

- Coffey C. E., Saxton J. A., Ratcliff G., Bryan R. N., Lucke J. F. (1999). Relation of education to brain size in normal aging: implications for the reserve hypothesis. Neurology, 53, 189.

- Cole S., Barber E. (2003). The problem. In S. Cole, E. Barber (Eds.), Increasing faculty diversity: The occupational choices of high achieving minority students. Cambridge (MA): Harvard University Press1–38. https://doi.org/10.4159/9780674029699-003.

- Collins D., Asante-Muhammed D., Hoxie J., Terry S. (2019). Dreams deferred: How enriching the 1% widens the racial wealth divide. Retrieved June 6, 2022, fromhttps://inequality.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/IPS_RWD-Report_FINAL-1.15.19.pdf.

- Cormack B., Harris D., Paradies Y. (2017). Racism and health service utilisation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One, 12(12), e0189900.

- Correro A. N., Nielson K. A. (2020). A review of minority stress as a risk factor for cognitive decline in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) elders. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 24, 2–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2019.1644570.

- Costello K., Greenwald B. D. (2022). Update on domestic violence and traumatic brain injury: A narrative review. Brain Sciences, 12, 122–139. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12010122.

- Crenshaw K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In Weisbert D. K. (Ed.), Feminist legal theory: Foundations (, pp. 383–395). Philadelphia: (Original work published 1989)Temple University Press.

- Cullen M. R., Lemeshow A. R., Russo L. J., Barnes D. M., Ababio Y., Habtezion A. (2022, March). Disease-specific health disparities: A targeted review focusing on race and ethnicity. Healthcare, 10(4), 603.

- Davies P. T., Thompson M. J., Li Z., Sturge-Apple M. L. (2022). The cognitive costs and advantages of children’s exposure to parental relationship instability: Testing an evolutionary-developmental hypothesis. Developmental Psychology, 58, 1485–1499. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001381.

- Del Toro J., Wang M.-T. (2022). The roles of suspensions for minor infractions and school climate in predicting academic performance among adolescents. American Psychologist, 77, 173–185. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000854.

- Doom J. R., Vanzomeren-Dohm A. A., Simpson J. A. (2015). Early unpredictability predicts increased adolescent externalizing behaviors and substance use: A life history perspective. Development and Psychopathology, 28, 1505–1516. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579415001169.

- Echemendia R. J., Thelen J., Meeuwisse W., Hutchison M. G., Rizos J., Comper P., et al (2020). Neuropsychological assessment of professional ice hockey players: A cross-cultural examination of baseline data across language groups. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 35, 240–256. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acz077.

- Elbulok-Charcape M. M., Rabin L. A., Spadaccini A. T., Barr W. B. (2014). Trends in the neuropsychological assessment of ethnic/racial minorities: A survey of clinical neuropsychologists in the United States and Canada. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 20, 353–361. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035023.

- Ellis B. J., Bianchi J., Griskevicius V., Frankenhuis W. E. (2017). Beyond risk and protective factors: An adaptation-based approach to resilience. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12, 561–587. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617693054.

- Emmons W., Ricketts L. (2017). College is not enough: Higher education does not eliminate racial and ethnic wealth gaps. Retrieved June 6, 2022, fromhttps://files.stlouisfed.org/files/htdocs/publications/review/2017-02-15/college-is-not-enough-higher-education-does-not-eliminate-racial-and-ethnic-wealth-gaps.pdf.

- Fernandez A. (2022) Education, the most powerful cultural variable? In A. Fernandez, J. Evans (Eds.), Understanding cross-cultural neuropsychology: Science, testing and challenges, New York: Routledge, 44–58. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003051497-5.

- Fincher C. L., Thornhill R., Murray D. R., Schaller M. (2008). Pathogen prevalence predicts human cross-cultural variability in individualism/collectivism. Proceedings of the Royal Society B, 275, 1279–1285. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2008.0094.

- Flores I., Casaletto K. B., Marquine M. J., Umlauf A., Moore D. J., Mungas D., et al (2017). Performance of Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites on the NIH toolbox cognition battery: The roles of ethnicity and language backgrounds. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 31, 783–797. Retrieved from. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2016.1276216. http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ntcn20.

- Foubert-Samier A., Catheline G., Amieva H., Dilharreguy B., Helmer C., Allard M., et al (2012). Education, occupation, leisure activities, and brain reserve: a population-based study. Neurobiology of Aging, 33, 423–e15.

- Franzen S., Papma J. M., van den Berg E., Nielsen T. R. (2021). Cross-cultural neuropsychological assessment in the European Union: A Delphi expert study. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 36, 815–830. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acaa083.

- Fredriksen-Goldsen K. I., Kim H. J., Barkan S. E., Muraco A., Hoy-Ellis C. P. (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay, and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103, 1802–1809. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110.

- Fujii D. (2017). Conducting a culturally-informed neuropsychological evaluation. Washington DC: American Psychological Association Press, https://doi.org/10.1037/15958-000.

- Fujii D. (2018). Developing a cultural context for conducting a neuropsychological evaluation with a culturally diverse client: The ECLECTIC framework. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 32, 1356–1392. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2018.1435826.

- Fujii D., Santos O., Malva L. D. (2022). Interpreter-assisted neuropsychological assessment: Clinical considerations. In A. Fernandez, J. Evans (Eds.), Understanding cross-cultural neuropsychology: Science, testing, and challenges, New York: Routledge, 135–147). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003051497-14.

- Fuligni A. J., Hardway C. (2004). Preparing diverse adolescents for the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children, 14, 98–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602796.

- García-Mora F., Mora-Rivera J. (2021). Exploring the impacts of Internet access on poverty: A regional analysis of rural Mexico. New Media & Society, 146144482110006-25. https://doi.org/10.1177/14614448211000650.

- Gimbert B., Bol L., Wallace D. (2007). The influence of teacher preparation on student achievement and the application of national standards by teachers of mathematics in urban secondary schools. Education and Urban Society, 40, 91–117.

- Godino A., Jayanthi S., Cadet J. L. (2015). Epigenetic landscape of amphetamine and methamphetamine addiction in rodents. Epigenetics, 10, 574–580.

- Goghari V. M. (2022). Reimagining clinical psychology. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne, 63, 169–178. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000328.

- González H. M., Tarraf W., Gouskova N., Gallo L. C., Penedo F. J., Davis S. M., et al (2015). Neurocognitive function among middle-aged and older Hispanic/Latinos: results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 30, 68–77.

- Gordon N. P., Lin T. Y., Rau J., Lo J. C. (2019). Aggregation of Asian-American subgroups masks meaningful differences in health and health risks among Asian ethnicities: An electronic health record based cohort study. BMC Public Health, 19, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7683-3.

- Greiffenstein M. F., Morgan J. E. (2020). Important theories in neuropsychology: A historical perspective. In Stucky K., Kirkwood M., Donders J. (Eds.), Clinical neuropsychology study guide and board review (, pp. 15–30). New York: Oxford University Press.

- Grigorenko E. L., Meier E., Lipka J., Mohatt G., Yanez E., Sternberg R. J. (2004). Academic and practical intelligence: A case study of the Yup'ik in Alaska. Learning and Individual Differences, 14, 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2004.02.002.

- Haag H., Jones D., Joseph T., Colantonio A. (2019). Battered and brain injured: Traumatic brain injury among women survivors of intimate partner violence—A scoping review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(4), 1270–1287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019850623.

- Hackett R. A., Ronaldson A., Bhui K., Steptoe A., Jackson S. E. (2020). Racial discrimination and health: A prospective study of ethnic minorities in the United Kingdom. BMC Public Health, 20, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09792-1.

- Hair N. L., Hanson J. L., Wolfe B. L., Pollak S. D. (2015). Association of child poverty, brain development, and academic achievement. JAMA Pediatrics, 169, 822–829. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1475.

- Haggarty P. (2013). Epigenetic consequences of a changing human diet. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 72, 363–371. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0029665113003376Haggarty (2013).

- Hajat A., Diez-Roux A. V., Sánchez B. N., Holvoet P., Lima J. A., Merkin S. S., et al (2013). Examining the association between salivary cortisol levels and subclinical measures of atherosclerosis: The Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 38, 1036–1046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2012.10.007.

- Hanks A., Solomon D., Weller C. (2018). Systematic inequality how america's structural racism helped create the Black-White wealth gap. Retrieved June 6, 2022, fromhttps://www.americanprogress.org/article/systematic-inequality/.

- Henrich J., Heine S. J., Norenzayan A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world?Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–83. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X.

- Hester N., Payne K., Brown-Iannuzzi J., Gray K. (2020). On intersectionality: How complex patterns of discrimination can emerge from simple stereotypes. Psychological Science, 31, 1013–1024. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797620929979.

- Howell J., Korver-Glenn E. (2021). The increasing effect of neighborhood racial composition on housing values, 1980–2015. Social Problems, 68, 1051–1071. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spaa033.

- Huang H.W., Huang C. M. (2022). Developing cross-cultural neuropsychology through the lens of cross-cultural cognitive neuroscience. In A. Fernandez, J. Evans (Eds.), Understanding cross-cultural neuropsychology: Science, testing and challenges, New York: Routledge. 29–43). https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003051497-4.

- Hyde L. W., Gard A. M., Tomlinson R. C., Burt S. A., Mitchell C., Monk C. S. (2020). An ecological approach to understanding the developing brain: Examples linking poverty, parenting, neighborhoods, and the brain. American Psychologist, 75, 1245.

- Ilanguages.com (2018). Multilingual people. Retrieved June 19, 2022, fromhttp://ilanguages.org/bilingual.php.

- Irani F., Byrd D. (2022). Cultural diversity in neuropsychological assessment. New York: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003051862.

- Jackson C. K., Mackevicius C. (2021). The distribution of school spending impacts (No. w28517). Massachusetts: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Jackson S. D., Mohr J. J., Sarno E. L., Kindahl A. M., Jones I. L. (2020). Intersectional experiences, stigma-related stress, and psychological health among Black LGBQ individuals. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88, 416–428. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000489.

- Jaramillo E. T., Willging C. E. (2021). Producing insecurity: Healthcare access, health insurance, and wellbeing among American Indian elders. Social Science and Medicine, 268, 113384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113384.

- Johnson A. H., Hill I., Beach-Ferrara J., Rogers B. A., Bradford A. (2020). Common barriers to healthcare for transgender people in the US Southeast. International Journal of Transgender Health, 21, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1700203.

- Klipfel K., Sweet J., Nelson N., Paul J., Moberg P. (2022). Gender and ethnic/racial diversity in clinical neuropsychology: Updates from the AACN, NAN, SCN 2020 practice and “salary survey”. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 1–55.

- Kovera M. B. (2019). Racial disparities in the criminal justice system: Prevalence, causes, and a search for solutions. Journal of Social Issues, 75, 1139–1164. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12355.

- Krogstad J. (2016). 5 Facts about latinos and education. Retrieved May 29, 2022, fromhttps://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2016/07/28/5-facts-about-latinos-and-education/.

- Liester M. B., Sullivan E. E. (2019). A review of epigenetics in human consciousness. Cogent Psychology, 6, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1668222.

- Lifshitz J., Crabtree-Nelson S., Kozlowski D. A. (2019). Traumatic brain injury in victims of domestic violence. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, and Trauma, 28, 655–659. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2019.1644693.

- Liu C. D., Yang L., Pu H. Z., Yang Q., Huang W. Y., Zhao X., et al (2017). Epigenetics regulates gene expression patterns of skeletal muscle induced by physical exercise. Yi Chuan=. Hereditas, 39, 888–896. https://doi.org/10.16288/j.yczz.16-364.

- Lockwood K. G., Marsland A. L., Matthews K. A., Gianaros P. J. (2018). Perceived discrimination and cardiovascular health disparities: A multisystem review and health neuroscience perspective. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1428, 170–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13939.

- Lozano-Ruiz A., Fasfous A. F., Ibanez-Casas I., Cruz-Quintana F., Perez-Garcia M., Pérez-Marfil M. N. (2021). Cultural bias in intelligence assessment using a culture-free test in Moroccan children. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 36, 1502–1510. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acab005.

- Manly J., Jacobs J., Touradji P., Small S., Stern Y. (2002). Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 8, 341–348. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1355617702813157.

- Margolin G., Gordis E. B. (2000). The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 445–479. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.51.1.445.

- Martin E. M., Fry R. C. (2018). Environmental influences on the epigenome: Exposure-associated DNA methylation in human populations. Annual Review of Public Health, 39, 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040617-014629.

- Matthews K., Schwartz J., Cohen S., Seeman T. (2006). Diurnal cortisol decline is related to coronary calcification: CARDIA study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 68, 657–661. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.psy.0000244071.42939.0e.

- McEwen B. S., Nasca C., Gray J. D. (2016). Stress effects on neuronal structure: Hippocampus, amygdala, and prefrontal cortex. Neuropsychopharmacology, 41, 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1038/npp.2015.171.

- Mersky J. P., Choi C., Lee C. P., Janczewski C. E. (2021). Disparities in adverse childhood experiences by race/ethnicity, gender, and economic status: Intersectional analysis of a nationally representative sample. Child Abuse and Neglect, 117, 105066. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105066.

- Mittal C., Griskevicius V., Simpson J. A., Sung S., Young E. S. (2015). Cognitive adaptations to stressful environments: When childhood adversity enhances adult executive function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109, 604–621. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000028.

- Mitrushina M., Boone K. B., Razani J., D'Elia L. F. (2005). Handbook of normative data for neuropsychological assessment. New York: Oxford University Press.

- National Congress of American Indians. (2021). Reducing disparities in the federal healthcare budget. Retrieved June 17, 2022, fromhttps://www.ncai.org/resources/ncai-publications/indian-country-budget-request/Healthcare.pdf.

- National Human Genome Research Institute. (2016). Epigenomics fact sheet. Maryland: National Institutes of Health. Retrieved June 20, 2022, fromhttps://www.genome.gov/27532724/epigenomics-fact-sheet/#al-5.

- NFL Player Health and Safety. (2017). NFL concussion diagnosis and management protocol. Retrieved June 14, 2022, fromhttps://www.nfl.com/playerhealthandsafety/resources/fact-sheets/nfl-head-neck-and-spine-committee-s-concussion-diagnosis-and-management-protocol

- NFL Player Health and Safety. (2020). Injury data since 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2022, fromhttps://www.nfl.com/playerhealthandsafety/health-and-wellness/injury-data/injury-data

- Nikolova Y. S., Hariri A. R. (2015). Can we observe epigenetic effects on human brain function?Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 19, 366–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.05.003.

- Noble K. G., Giebler M. A. (2020). The neuroscience of socioeconomic inequality. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 36, 23–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.05.007.

- Nweze T., Nwoke M. B., Nwufo J. I., Aniekwu R. I., Lange F. (2021). Working for the future: Parentally deprived Nigerian children have enhanced working memory ability. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 62, 280–288.

- Odling-Smee F. J., Laland K. N., Feldman M. (2003). Niche construction: The neglected process in evolution. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

- Our World in Data. (n.d.). Average total years of schooling for adult population years. Retrieved August 19, 2021, fromhttps://ourworldindata.org/grapher/mean-years-of-schooling-long-run?tab=table.

- Pandey S. C., Kyzar E. J., Zhang H. (2017). Epigenetic basis of the dark side of alcohol addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology, 122, 74–84.

- Perreira K. M., Allen C. D., Oberlander J. (2021). Access to health insurance and health care for Hispanic children in the United States. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 696, 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027162211050007.

- Pew Research Center (2017a). Educational attainment of Bhutanese population in the U.S., 2015. Washington DC. Retrieved May 29, 2022, fromhttps://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/chart/educational-attainment-of-bhutanese-population-in-the-u-s/.

- Pew Research Center (2017b). Educational attainment of Laotian population in the U.S., 2015Retrieved May 29, 2022, fromhttps://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/chart/educational-attainment-of-laotian-population-in-the-u-s/.

- Phelps E. (2009). The human amygdala and the control of fear. In Whalen P., Phelps E. (Eds.), The human amygdala, (pp. 204–219). New York: Guilford Press.

- Ponsford J. (2017). International growth of neuropsychology. Neuropsychology, 31, 921–933. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000415.

- Prydz E. B., Wadhwa D. (2019). Classifying countries by income. Retrieved August 19, 2021, fromhttps://datatopics.worldbank.org/world-development-indicators/stories/the-classification-of-countries-by-income.html.

- Qu Y., Jorgensen N. A., Telzer E. H. (2021). A call for greater attention to culture in the study of brain and development. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16, 275–293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620931461.

- Red Road (2022). Education of the first people. Retrieved May 29, 2022, fromhttps://theredroad.org/issues/native-american-education/

- Rosenthal L. (2016). Incorporating intersectionality into psychology: An opportunity to promote social justice and equity. American Psychologist, 71, 474–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0040323.

- Ross R. (1999). Atherosclerosis: An inflammatory disease. New England Journal of Medicine, 340, 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199901143400207.

- Sánchez O., Judd T. (2022). Multicultural education and training in neuropsychology: Let's talk about skill acquisition! In F. Irani (Ed.), Cultural diversity in neuropsychological assessment18–33. New York: Routledge, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003051862-4.

- Sapienza C., Issa J.-P. (2016). Diet, nutrition, and cancer epigenetics. Annual Review of Nutrition, 36, 665–681. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-nutr-121415-112634.

- Schulz A. J., Mentz G., Lachance L., Johnson J., Gaines C., Israel B. A. (2012). Associations between socioeconomic status and allostatic load: Effects of neighborhood poverty and tests of mediating pathways. American Journal of Public Health, 102, 1706–1714. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2011.300412.

- Sénéchal M., LeFevre J. (2002). Parental involvement in the development of children’s reading skill: A five-year longitudinal study. Child Development, 73, 445–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00417.

- Shrider E., Kollar M., Chen F., Semega J. (2021). Income and poverty in the United States: 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2022, fromhttps://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html.

- Sosina V. E., Weathers E. S. (2019). Pathways to inequality: Between-district segregation and racial disparities in school district expenditures. AERA Open, 5(3), 233285841987244. https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419872445.

- Stern Y. (2003). The concept of cognitive reserve: A catalyst for research. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 25, 589–593. https://doi.org/10.1076/jcen.25.5.589.14571.

- Sternberg R. J., Nokes C., Geissler P. W., Prince R., Okatcha F., Bundy D. A., et al (2001). The relationship between academic and practical intelligence: A case study in Kenya. Intelligence, 29, 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(01)00065-4.

- von Stumm S., Smith-Woolley E., Ayorech Z., McMillan A., Rimfeld K., Dale P. S., et al (2020). Predicting educational achievement from genomic measures and socioeconomic status. Developmental Science, 23, e12925. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12925.

- Sue D. W., Calle C. Z., Mendez N., Alsaidi S., Glaeser E. (2020). Microintervention strategies: What you can do to disarm and dismantle individual and systemic racism and bias. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Tawakol A., Ishai A., Takx R., Figueroa A., Ali A., Kaiser Y., et al (2017). Relation between resting Amygdalar activity and cardiovascular events: A longitudinal and cohort study. Lancet (London, England), 389, 834–845. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31714-7.

- Trentacosta C. J., Davis-Kean P., Mitchell C., Hyde L., Dolinoy D. (2016). Environmental contaminants and child development. Child Development Perspectives, 10, 228–233. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12191.

- United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2021). Employment projections. Retrieved June 6, 2022, fromhttps://www.bls.gov/emp/chart-unemployment-earnings-education.htm.

- United States Census Bureau. (2021). U.S. Census quick facts. Retrieved August 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219.

- United States Department of Labor Women’s Bureau. (2020). Women's earnings by race, ethnicity, and educational attainment as a percentage of White men's earnings (annual). Retrieved June 12, 2022, fromhttps://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/data/earnings/Women-earnings-race-ethnicity-educational-attainment-percentage-Whitemen-earnings.

- United States Government Accountability office (2020). Domestic violence improved data needed to identify the prevalence of brain injuries among victims. Retrieved June 14, 2022, fromhttps://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-534.pdf.

- VandenBos G. R. (2007). APA dictionary of psychology. Washington DC: American Psychological Association Press.

- Wang X., Zhu N., Chang L. (2022). Childhood unpredictability, life history, and intuitive versus deliberate cognitive styles. Personality and Individual Differences, 184, 111225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111225.

- Weir K. (2016). Inequality at school: What’s behind the racial disparity in our education system. Monitor on Psychology, 47(10), 44–47.

- Weller C., Sharpe R., Solomon D., Cook L. (2020). Redesigning federal funding of research and development: The importance of including Black innovators. Retrieved June 6, 2022, fromhttps://www.americanprogress.org/article/redesigning-federal-funding-research-development/.

- Williams D. R., Lawrence J. A., Davis B. A., Vu C. (2019). Understanding how discrimination can affect health. Health Services Research, 54, 1374–1388. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.13222.

- World Bank (n.d.) GDP (current US$). Retrieved August 19, 2021, fromhttps://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.CD?name_desc=true.

- Worldometer (n.d.) world’s population. Retrieved August 19, 2021, fromhttps://www.worldometers.info/world-population/#religions.

- Yao B., Christian K. M., He C., Jin P., Ming G.-I., Song H. (2016). Epigenetic mechanisms in neurogenesis. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 17, 537–549. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn.2016.70.

- Yehuda R., Bierer L. M. (2008). Transgenerational transmission of cortisol and PTSD risk. Progress in Brain Research, 167, 121–135.

- Young E. S., Frankenhuis W. E., DelPriore D. J., Ellis B. J. (2022). Hidden talents in context: Cognitive performance with abstract versus ecological stimuli among adversity-exposed youth. Child Development., 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13766.

- Zahodne L. B., Morris E. P., Sharifian N., Zaheed A. B., Kraal A. Z., Sol K. (2020). Everyday discrimination and subsequent cognitive abilities across five domains. Neuropsychology, 34, 783–790. https://doi.org/10.1037/neu0000693.

- Zahodne L. B., Neika Sharifian A., Kraal Z., Morris E. P., Sol K., Zaheed A. B., et al (2022). Longitudinal associations between racial discrimination and hippocampal and white matter hyperintensity volumes among older Black adults. Social Science and Medicine., 114789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114789.

- Zannas A. S., Arloth J., Carrillo-Roa T., Iurato S., Röh S., Ressler K. J., et al (2015). Lifetime stress accelerates epigenetic aging in an urban, African American cohort: Relevance of glucocorticoid signaling. Genome Biology, 16, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13059-015-0828-5.

- Zeigler K., Camarota S. (2019). 67.3 Million in the United States spoke a foreign language at home in 2018. Retrieved August 19, 2021, fromhttps://cis.org/Report/673-Million-United-States-Spoke-Foreign-Language-Home-2018.