Key Points

Healthy lifestyle behaviours are essential to promote health, yet few older adults meet recommended guidelines.

The six pillars of lifestyle medicine and 5Ms (i.e. Mind, Mobility, Medications, Multicomplexity, Matters Most), of geriatric medicine can promote health through transdisciplinary collaboration.

Key gaps in current exercise and lifestyle medicine research, practice and policy for older adults are identified.

Breaking down practice silos, integrating lifestyle and geriatric medicine and individual context may sustain healthy behaviours.

Introduction

Lifestyle behaviours can reduce the risk of preventable deaths by up to 40% []. Healthy lifestyle behaviours are crucial to promote optimal health in older adults, slow age-related functional decline and prevent premature death from chronic conditions (e.g. cardiovascular disease, diabetes, cancer). Preventing chronic conditions could reduce healthcare costs by up to 85% []. Yet, few older adults meet the guidelines for healthy lifestyle behaviours. Less than 15% of older adults 65 years of age and older in the United States meet physical activity guidelines (i.e. 150 minutes or more of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity and 2 days of muscle-strengthening physical activity each week), [] and less than 50% meet dietary recommendations []. Changing lifestyle health behaviours remains a significant public health challenge, particularly for older adults.

In 2004, lifestyle medicine (LM) arose to address factors associated with lifestyle behaviours and is rapidly growing in the United States and internationally []. The American College of Lifestyle Medicine defines LM as ‘a medical specialty that uses therapeutic lifestyle interventions as a primary modality to treat chronic conditions including, but not limited to, cardiovascular diseases, type 2 diabetes, and obesity’ []. The six pillars of LM include a whole-food plant-based diet, physical activity, sleep, stress management, avoidance of risky substances and positive social connections []. Strengthening lifestyle pillars, even later in life can increase health span and decrease years of chronic disease and disability []. Prior LM research focused mostly on primary and secondary prevention [] and often overlooked tertiary trials for older adults with multiple comorbidities and disabilities.

The aim of this paper is to propose an updated framework of LM for older adults that integrates their individual contexts and experiences, the geriatrics 5Ms and principles of LM through a novel transdisciplinary approach. For the purposes of this paper, we define transdisciplinary as an approach that integrates knowledge and perspectives across disciplines to solve a problem or need []. Here, as a transdisciplinary group of clinician scientists—including occupational therapists, physical therapists and physicians—we highlight the need to tailor LM to address older adults’ complex contexts and care needs and highlight gaps and opportunities to advance research, practice and policy.

Lifestyle Medicine and transdisciplinary origins

LM utilizes a person-centered approach and aims to identify and treat the root cause of disease through daily healthy habits to prevent, treat and reverse chronic disease []. In contrast, conventional medicine reactively addresses symptoms []. LM began in family medicine with transdisciplinary origins, drawing from numerous disciplines (e.g. nutrition, positive psychology, behaviour change, health coaching, sleep medicine). Certifications in LM have since expanded from family medicine across medical specialties to allied health professions (e.g. dieticians, nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists, pharmacists) [, ].

Most of the early landmark LM studies focus on primary and secondary prevention with similar or better impacts on chronic disease as pharmacotherapies [, ]. The seminal Diabetes Prevention Program (n = 3234), involved diet, exercise and stress management and decreased the incidence of diabetes by 58%, exceeding the impact of the medication metformin in individuals with prediabetes with a mean age of 50 []. Additionally, the Lifestyle Heart Trial (n = 48), involving a 10% fat, whole-food vegetarian diet, stress management, smoking cessation, aerobic exercise and group support demonstrated the reversal of coronary artery disease with the average percent diameter stenosis at baseline improving by 4.5% at 1 year and 7.9% after 5 years []. The Lyon Heart Study of 600 participants randomized to a mediterranean diet intervention statin therapy, found a similar 50% reduction in the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction at 46 months in both groups []. All of these studies had a majority of participants who were middle aged or in the young-old (65–74 years) category, [] focused on primary and secondary prevention, and had samples with a majority of Caucasian individuals of European decent. Gaps exist in our understanding of how LM can be feasible and sustainable for older adults with varying comorbidities and diverse lived experiences with advancing age.

Integrating Lifestyle Medicine with the Geriatric 5Ms: the Older Adult Lifestyle Medicine Framework

The Older Adult Lifestyle Medicine Framework integrates the six pillars of LM and is tailored to the complex lived experiences of older adults (Figure 1). The framework incorporates a person-centered approach (Geriatric 5Ms), while situating the person in their daily context within their community and broader environment. This framework acknowledges the diverse lived experiences of older adults including their intersectional identities and social determinants of health (SDOH) and determinants of health (access to regular primary care visits, vaccines, etc.). [] The framework requires broader transdisciplinary perspectives and collaborations beyond the traditional medical subspecialties and allied health professions.

Figure 1

The Older Adult Lifestyle Medicine Framework. Notes. The Older Adult Lifestyle Medicine framework utilizes a multi-level approach that requires transdisciplinary knowledge and collaborations at each level.

The Geriatric 5Ms of the person and the six lifestyle pillars

The Geriatric 5Ms is a comprehensive approach within the Age-Friendly Health Systems Initiative to deliver optimized and tailored care and address unique health needs of older adults []. The John A Hartford Foundation and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement developed the 4Ms—What Matters, Medication, Mentation, Mobility—aim to provide high-quality, evidence-based care for all older adults. The framework was later expanded by the American Geriatrics Society to include the 5th M—Multicomplexity—emphasizing the importance of addressing the older adult as a whole person with multiple chronic conditions and complex biopsychosocial needs.

‘What Matters Most’ to individuals is at the core of person-centered care. When caring for older adults—regardless of discipline or specialty—it is important that shared decision making occurs in the context of an individual’s preferences and goals (i.e. goal concordant care), with the understanding that these often change over time. Decision-making in this context for older adults involves (i) communicating patient preferences and goals; (ii) estimating prognosis based on disease and non-diseases factors; and (iii) understanding the role that cognitive, mobility and sensory impairments have on goal attainment []. Examples of what matters most to older adults in decision-making includes cognitive and physical functioning and connections with family, friends and ‘God or a higher power’ []. Importantly, ‘What Matters Most’ varies between individuals, and there is currently lack of consensus on how to incorporate this ‘M’ into healthcare practice efficiently and effectively, including in exercise and lifestyle medicine. Applying a ‘What Matters Most’ approach is crucial for identifying older adults’ priorities in lifestyle behaviour changes that are feasible and sustainable based on their level of function and daily contexts.

The literature on high quality LM trials in palliative care and hospice settings are promising but scarce for older adults with advanced illness []. LM interventions for older adults with advanced or terminal illness have the potential to improve symptom management (e.g. pain, anxiety, insomnia, edema), function, and quality of life in palliative care and hospice settings [, ]. A recent review of LM interventions in palliative care and hospice identified four categories: exercise, nutrition, stress management and substance use []. Notably, exercise and nutrition can improve quality of life in older adults with Alzheimer’s disease (AD []. Stress management interventions had mixed findings for improving pain with music therapy, mindfulness and meditation may reduce depression and anxiety in older adults with cancer []. Barriers included feasibility, acceptability and a lack of high quality trials. Future research should include feasibility and acceptability to guide randomized controlled trials of LM interventions. Advancing a ‘What Matters’ approach at the systems level will involve perspectives from older adults, their caregivers and interdisciplinary care teams as key collaborators in this process.

Mind of the 5Ms focuses on mental and cognitive health. While all conditions that affect mood and mental and cognitive health are part of this M, ‘Mind’ also encompasses specific geriatric syndromes, including depression, delirium and dementia. ‘Mind’ reflects a critical component of the 5Ms as cognitive abilities often decline with age and impairments are associated with disability. Based on epidemiological data, risk factors such as obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, smoking and lack of cognitive stimulation are associated with different subtypes of dementia []. To address risk factors, lifestyle interventions were targeted to address chronic conditions.

LM can address depression and delirium in older adults. The MedDiet is a lifestyle intervention that addressed depression with a Mediterranean diet with nuts, legumes, and fish oil supplementation. [] The MedDiet significantly reduced depression in adults over age 18 when compared to a control group (t = −2.24, P = .03) and improved and sustained quality of life three months later (t = 2.10, P = .04) []. Delirium has also shown improvements with multicomponent interventions implemented in daily life (reorientation, early mobilization, activities, hydration, nutrition, sleep, hearing and vision adaptations) with a recent metanalysis reporting a significant reduction in delirium incidence by 44% (Odds Ratio [OR], 0.56; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.42–0.76) and the rate of falls by 64% (OR, 0.36; 95% CI: 0.22–0.61) [].

LM has grown over the past decades to address cognitive health and dementia prevention in middle aged and older adults at risk for mild cognitive impairment and AD. The Finnish Geriatric Intervention Study to Prevent Cognitive Impairment and Disability (FINGER), was the first large-scale LM study to address risk factors for cognitive decline and AD. [] The intervention involved a multidomain approach (e.g. diet, exercise, cognitive training, stress reduction, vascular risk monitoring) to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk older adults found cognition was sustained or improved in the intervention group compared to the control (95% CI: 0.002–0.042, P = .030) []. The FINGER study is being replicated globally []. A multidomain lifestyle intervention (whole foods vegan diet, aerobic exercise, stress management and support group) to prevent and potentially reverse AD in older adults with early pathology (mean age of 73.5) showed significantly less pathology progression (6.4% increase Aβ42/40 ratio, P = .003) and cognitive decline than the control group across multiple cognitive evaluations. However, greater than ~71% adherence to the lifestyle intervention was needed to result in cognitive changes []. A gap remains in tertiary LM interventions for older adults with moderate to advanced AD. Future research should focus on tertiary LM trials could improve health outcomes based on ‘What Matters Most’ to older adults living with advanced AD.

Medication represents an appropriate use of medication in older adults; it also encompasses addressing polypharmacy, avoiding high-risk medication and aligning medication to not interfere with the other Ms of 5Ms. ‘Medication’ often includes polypharmacy (i.e. the use of five or more medications or supplements) and is highly prevalent (e.g. as high as 65% in the U.S.) among older adult []. When indicated, polypharmacy can be beneficial in managing chronic disease and treating symptoms impacting health-related quality of life. However, there are multiple associated harms related to inappropriate medication use, such as adverse drug reactions, hospitalizations, delirium, falls, impaired mobility, and mortality [].

As shown in observational and interventional studies, LM has the potential to reduce unnecessary—or potentially inappropriate—use of medication in older adults. A multicomponent lifestyle intervention (diet, aerobic exercise, stress management, group support) of 51 participants to reduce AD risk lowered Aβ42/40 in 20 weeks, which is faster than the drug Lecanemab, that can take 18 months []. Similarly the Lyon Heart Study of 600 participants, found a 50% reduction in the secondary prevention of myocardial infarction at 46 months with a mediterranean diet that was comparable to statins []. In a single-arm clinical trial evaluating a multimodal lifestyle intervention incorporating physical exercise, dietary restriction and diabetes education in middle-aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes, pill count was significantly lower per day at 1 year among participants 1.3 ± 0.3 at 12 months (P < .001) and decreased the annual cost of medications (€135.1 ± 43.9) (P = .03) []. Weaknesses of these studies were a small and non-diverse sample size (n = 26) []. Additional interventional studies targeting polypharmacy (e.g. deprescribing) in individuals with multiple comorbidities using multimodal lifestyle strategies for older adults are critically needed for reducing polypharmacy within a LM framework.

Mobility refers to the ability to move or walk freely and easily. Mobility decline in older adults can result in deconditioning and limited participation in physical activity, which may worsen the severity of chronic conditions (e.g. cardiopulmonary disease, kidney disease, rheumatologic diseases). Impaired mobility is also associated with falls and accelerated functional dependence []. The interplay between chronic conditions and mobility can be bidirectional. For example, while cardiovascular disease has been linked to reduced mobility, reduced mobility resulting in physical inactivity is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease, thereby creating a negative spiral of health conditions. Inversely, improved mobility can increase walking and exercise [], decrease risk for cardiovascular disease, and risk of premature death [].

Impairments in mobility are modifiable with low-cost interventions (e.g. walking, Tai Chi). Walking is a low-risk physical activity known for its numerous health benefits []. In a 10-year longitudinal study, older adults 65 and older, who walked 8000 steps or more compared with those who walked 4000 steps or less decreased their death rates by ~80%, regardless of walking speed []. Tai Chi is another low-cost intervention that can improve functional mobility and balance for older adults. A recent meta-analysis of 12 studies with 2901 participants found Tai Chi significantly improved performance on the Timed-Up-and-Go (Standardized Mean Difference = −0.18, [−0.33 to −0.03], P = .040) and the 50-foot walking test (Mean Difference = −1.84 s, [−2.62 to −1.07], P < .001) when compared with conventional exercise (e.g. resistance training) []. Limitations of these studies were samples of community-dwelling older adults without disabilities and complex comorbidities. Future research should include tertiary trials for older adults living in long-term care with multiple comorbidities.

Multicomplexity refers to the presence of concomitant multimorbidity, geriatric syndromes and psychosocial factors central to the health of many older adults. Multicomplexity is found in >50% of adults above 60 years of age were associated with multiple adverse health outcomes such as increased hospitalization, mortality and decreased physical functioning []. Geriatric syndromes, including frailty and pre-frailty, are also highly prevalent in older adults and often coincide with multimorbidity, which may lead to increased reliance on care partners for routine tasks. Multimorbidity often may be intertwined with SDOH that can exacerbate adverse health outcomes. For example, while frailty has been linked to loneliness and social isolation, loneliness and social isolation also have been associated with frailty progression [].

LM could help improve quality of life for individuals living with multiple comorbidities. The interplay between features of multicomplexity (e.g. geriatric syndromes, medical conditions, low socioeconomic status) and lifestyle factors (e.g. interpersonal connection, sleep quality, physical activity) is also bidirectional. Additionally, AD has been found to be associated bidirectionally with sleep–wake disturbance and cognitive function. Changes in sleep–wake regulation can increase Aβ accumulation, and Aβ deposits can also lead to sleep disturbances, which can occur in AD 25–60% of the time [].

As lifestyle factors are modifiable, efforts to promote healthy lifestyle have the potential to produce gains in clinically relevant outcomes related to multicomplexity. An intensive lifestyle intervention incorporating caloric restriction and physical activity evaluated in middle aged and older adults with type 2 diabetes and elevated body mass index was associated with a 9% slower increase in multimorbidity over 8 years relative to diabetes support and education []. Because underlying multicomplexity can impact individual engagement with healthy lifestyle behaviours, there is critical need for evidence-based strategies to address the bidirectional relationship of lifestyle factors and multicomplexity. Further investigation involving transdisciplinary expertise will be paramount to achieve scientific progress.

Community

Community is defined as family, friends, social network, local healthcare and community-based organizations. LM has the potential to drastically improve health when implemented on a community level and is crucial for sustainability []. The North Karelia Project in Finland involved social and educational programs to reduce modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease. The project demonstrated how a community LM intervention transformed North Karelia Finland from having the highest cardiovascular mortality rates in the world to reducing death rates by 2/3 and cardiovascular disease by 84% between 1972 and 2014 [].

Cultural factors and SDOH have been identified as barriers to successfully implementing LM []. The American College of Lifestyle Medicine recently started the Health Equity for Lifestyle Medicine Initiative, which focuses on clinician education about health equity and fostering community-based participatory research and capacity building through community partnerships to expand services to individuals who are underrepresented in LM []. While LM is working to expand beyond the individual and cultivate community partnerships, continued progress in using person-centered outcomes, community-based participatory research practices, and shared decision-making will be paramount to advancing LM interventions in communities. Future research could utilize participatory community engagement studios or co-design methods [], to obtain input from older adults in the planning phases of lifestyle interventions to understand community priorities, sociocultural and environmental contexts. Such approaches can support effective recruitment, retention and uptake [, ], but also provide insights into how to inform policy decisions and translate research findings into actionable recommendations with potential adaptation by wider populations of older adults.

Environment

The environment includes the built environment and the sociopolitical environment, including government, healthcare systems, large non-profit organizations and environmental factors contributing to planetary health (e.g. climate crisis, pollution), a new initiative in LM []. Factors such as neighbourhood walkability (e.g. residential density, intersection frequency), traffic conditions, pollution, safety and access to green space and recreational facilities can impact opportunities for exercise and leisure activities [, ]. A cross-sectional study of older adults (mean age 74) living with lower socioeconomic resources found a 10-point increase in Street Smart Walk Score (walkability) was associated with a 45% greater chance of walking for transportation compared with none (OR = 1.45, 95% CI: 1.18, 1.78) with sociodemographic, physical function and attitudinal factors as significant predictors of physical activity []. Improving these aspects of the built environment can promote physical activity and social engagement. Future research should include natural experimental study designs and community partnerships to address walkability, leveraging online tools (e.g. Street Smart Walking Score) and new transdisciplinary perspectives of health geographers, parks and recreation professionals, and city planners.

Lastly, LM interventions face challenges with adherence and sustainability due to organizational and sociopolitical contexts. Many LM interventions involve multiple components and require time, energy, and resources to implement and sustain []. For example, while a physical activity intervention was feasible, retention and adherence were suboptimal with only 67% (36/48) of participants finishing the study. Similarly, a LM intervention for decreasing obesity and co-morbidities in primary care struggled with protocol adherence, long-term sustainability, and was dependent on ‘funding opportunities and collaborations’ []. While initially, the intervention was covered by health insurance, the policy changed and coverage was withdrawn, highlighting the need for a multi-pronged sustainability strategy (e.g. healthcare system and community-based organizations).

One approach to addressing sustainability is designing LM interventions for dissemination from the beginning with community-based organizations or healthcare systems and older adults. An example of this is a market viability assessment of a packaged intensive health behaviour and lifestyle intervention for childhood obesity []. They underscored the importance of aligning with healthcare organization performance metrics, reimbursement and understanding the different priorities of partners (organizational versus end-user) []. Transdisciplinary collaborations with healthcare systems and community-based organizations (parks and recreation, older adult centers) and designing LM for dissemination could contribute to long-term sustainability of LM interventions.

Integrating transdisciplinary research in lifestyle medicine: gaps and opportunities

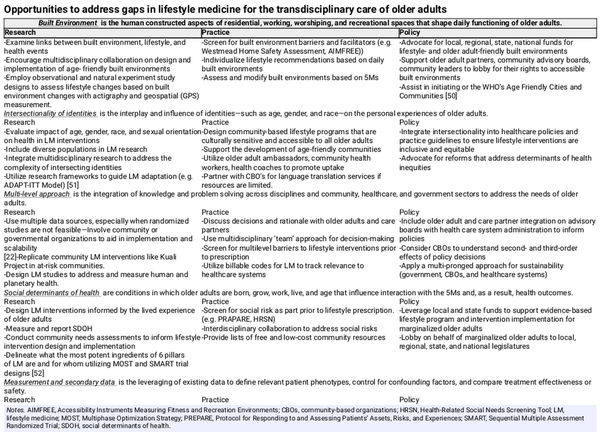

Using the 5Ms framework, we identified key gaps in current LM research, practice and policy that can be addressed with a transdisciplinary approach. Specific gaps relevant to the 5 M categories of Mind, Mobility, Medications and Multicomplexity require attention to older adults’ daily contexts that are shaped by SDOH and the built environment, which can provide barriers to their ability to access and participate in exercise and lifestyle changes. We summarize opportunities to address these key gaps in lifestyle medicine for the transdisciplinary care of older adults in Table 1.

Key themes across these gaps and opportunities underscore the necessity of designing and implementing LM interventions that meet older adults’ preferences and needs using a multilevel transdisciplinary approach. Interventions that align with older adults’ diverse identities and lived experiences (e.g. varied SDOH they encounter) is critical. Partnerships across disciplines and sectors (e.g. public health, parks and recreation, community-based organizations, healthcare) can address varied SDOH in both urban and rural contexts that impact a person’s ability to engage in a healthy lifestyle and may broaden real-world impact. For example, researchers and policy makers led New York City’s Community Parks Initiative to address the built environment with park redesign and renovation. This project was positively associated with lifestyle changes, including higher park use in low-income neighbourhoods []. Efforts to address these gaps in LM will help promote the ultimate goal of improving the health of older adults through sustained behaviour change.

Conclusion

The six pillars of LM, 5Ms of Geriatric Medicine, and individual daily contexts are deeply intertwined and impact older adults’ health. The Older Adult Lifestyle Medicine Framework utilizes a multi-level approach to guide research, practice and policy by considering the 5 M’s of older adults situated in community and the broader environment that impacts their ability to engage and sustain healthy lifestyle changes. Expanding partnerships beyond traditional medical subspecialities and allied health disciplines to include older adults, caregivers, community-based organizations, city planning and policymakers can bolster the growing field of LM to improve the health of older adults.

Acknowledgements

Sponsor’s role: The American Federation for Aging Research serves as the National Program Office for the Clin-STAR Coordinating Center. The Clin-STAR Coordinating Center is funded by the National Institutes of Health National Institute on Aging under award U24AG065204. Authors are members of the Clin-STAR Exercise and Lifestyle Medicine Research Interest Group. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funder.

References

- 1. Garcia MC, Rossen LM, Matthews K, et al Preventable premature deaths from the five leading causes of death in nonmetropolitan and metropolitan counties, United States, 2010-2022. MMWR Surveill Summ 2024;73:1–11. 10.15585/mmwr.ss7302a1.

- 2. Friedman SM, Mulhausen P, Cleveland ML, et al Healthy aging: American Geriatrics Society white paper executive summary. J Am Geriatr Soc 2019;67:17–20. 10.1111/jgs.15644.

- 3. U.S. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. The Power of prevention; chronic disease the public health challenge of the 21st century. 2009. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/5509.

- 4. Choi YJ, Crimmins EM, Kim JK, et al Food and nutrient intake and diet quality among older Americans. Public Health Nutr 2021;24:1638–47. 10.1017/S1368980021000586.

- 5. , et al Foundations of lifestyle medicine and its evolution. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes 2024;8:97–111. 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2023.11.004.

- 6. . What is Lifestyle Medicine? https://lifestylemedicine.org/ (10 March 2025, date last accessed).

- 7. , et al Aging, lifestyle and dementia. Neurobiol Dis 2019;130:104481.

- 8. . Reduction in the Incidence of Type 2 Diabetes with Lifestyle Intervention or Metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346. 10.1056/NEJMoa012512.

- 9. , et al Intensive Lifestyle Changes for Reversal of Coronary Heart Disease., 1998. 10.1001/jama.280.23.2001.

- 10. , et al Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. New England journal of medicine 2018;378:e34.

- 11. , et al Mediterranean diet, traditional risk factors, and the rate of cardiovascular complications after myocardial infarction: final report of the Lyon Diet Heart Study. Circulation 1999;99:779–85. 10.1161/01.CIR.99.6.77.

- 12. , et al Conceptualising transdisciplinary integration as a multidimensional interactive process. Environ Sci Policy 2021;118:18–26. 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.12.005.

- 13. Lifestyle Medicine. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2020;31:515–26. 10.1016/j.pmr.2020.07.006.

- 14. , et al Reduction of Myocardial Infarction and All-Cause Mortality Associated to Statins in Patients Without Obstructive CAD. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2021;14:2400–10. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.05.022.

- 15. , et al Differences in youngest-old, middle-old, and oldest-old patients who visit the emergency department. Clin Exp Emerg Med 2018;5:249–55. 10.15441/ceem.17.261.

- 16. . Healthy People 2030: Social Determinants of Health. 2021. https://odphp.health.gov/healthypeople/priority-areas/social-determinants-health (3 March 2025, date last accessed).

- 17. The Geriatrics 5M’s: A New Way of Communicating What We Do. J Am Geriatr Soc 2017;65:2115–2115. 10.1111/jgs.14979.

- 18. , et al Outcome goals and health care preferences of older adults with multiple chronic conditions. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e211271. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.1271.

- 19. , et al What matters most to older adults: Racial and ethnic considerations in values for current healthcare planning. J Am Geriatr Soc 2023;71:3254–66. 10.1111/jgs.18525.

- 20. , et al Lifestyle Medicine Interventions in Patients With Advanced Disease Receiving Palliative or Hospice Care. Am J Lifestyle Med 2020;14:243–57. 10.1177/1559827619830049.

- 21. What Matters: Geriatrics, Lifestyle Medicine, and Palliative Care. Lifestyle Medicine. 4th ed. CRC Press, 2024. 10.1201/978100322779.

- 22. , et al Home-Based Exercise Program Improves Balance and Fear of Falling in Community-Dwelling Older Adults with Mild Alzheimer's Disease: A Pilot Study. J Alzheimers Dis 2017;59:565–74. 10.3233/JAD-170120.

- 23. . Aerobic exercise improves quality of life, psychological well-being and systemic inflammation in subjects with Alzheimer's disease. Afr Health Sci 2016;16:1045–55. 10.4314/ahs.v16i4.22.

- 24. . Tube feeding in advanced dementia: the metabolic perspective. BMJ. 2006;333:1214–5. 10.1136/bmj.39021.785197.47.

- 25. , et al Does feeding tube insertion and its timing improve survival? J Am Geriatr Soc 2012;60:1918–21. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.04148.x.

- 26. , et al A Mediterranean-style dietary intervention supplemented with fish oil improves diet quality and mental health in people with depression: A randomized controlled trial (HELFIMED). Nutr Neurosci 2019;22:474–87. 10.1080/1028415X.2017.1411320.

- 27. . Effectiveness of multicomponent nonpharmacological delirium interventions: a meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med 2015;175:512–20. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.7779. Erratum in: JAMA Intern Med. 2015 Apr;175(4):659. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.0994.

- 28. , et al A 2 year multidomain intervention of diet, exercise, cognitive training, and vascular risk monitoring versus control to prevent cognitive decline in at-risk elderly people (FINGER): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet 2015;385:2255–63. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60461-5.

- 29. . World Wide FINGERS. https://www.alz.org/wwfingers/overview.asp (20 March 2025, date last accessed).

- 30. , et al Effects of intensive lifestyle changes on the progression of mild cognitive impairment or early dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: a randomized, controlled clinical trial. 10.1186/s13195-024-01482-z.

- 31. Wimmer BC, Bell JS, Fastbom J, et al Medication Regimen Complexity and Number of Medications as Factors Associated With Unplanned Hospitalizations in Older People: A Population-based Cohort Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2016;71:831–7. 10.1093/gerona/glv219.

- 32. Young EH, Pan S, Yap AG, et al Polypharmacy prevalence in older adults seen in United States physician offices from 2009 to 2016. PLoS One 2021;16:e0255642. 10.1371/journal.pone.0255642.

- 33. Lanhers C, Walther G, Chapier R, et al Long-term cost reduction of routine medications following a residential programme combining physical activity and nutrition in the treatment of type 2 diabetes: a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open 2017;7:e013763. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013763.

- 34. Maresova P, Krejcar O, Maskuriy R, et al Challenges and opportunity in mobility among older adults – key determinant identification. BMC Geriatr 2023;23:447. 10.1186/s12877-023-04106-7.

- 35. Brahms CM, Hortobágyi T, Kressig RW, et al The Interaction between Mobility Status and Exercise Specificity in Older Adults. Exerc Sport Sci Rev 2021;49:15–22. 10.1249/JES.0000000000000237.

- 36. Ungvari Z, Fazekas-Pongor V, Csiszar A, et al The multifaceted benefits of walking for healthy aging: from Blue Zones to molecular mechanisms. Geroscience 2023;45:3211–39. 10.1007/s11357-023-00873-8.

- 37. Saint-Maurice PF, Troiano RP, Bassett DR, et al Association of Daily Step Count and Step Intensity with Mortality among US Adults. JAMA 2020;323:1151–60. 10.1001/jama.2020.1382.

- 38. Li Y, Liu M, Zhou K, et al The comparison between effects of Taichi and conventional exercise on functional mobility and balance in healthy older adults: a systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health 2023;11, 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1281144.

- 39. Chowdhury SR, Chandra Das D, Sunna TC, et al Global and regional prevalence of multimorbidity in the adult population in community settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine 2023;57:101860. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2023.101860.

- 40. Hanlon P, Wightman H, Politis M, et al The relationship between frailty and social vulnerability: a systematic review. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2024;5(3):e214–e226. 10.1016/S2666-7568(23)00263-5.

- 41. Wang C, Holtzman DM. Bidirectional relationship between sleep and Alzheimer’s disease: role of amyloid, tau, and other factors. Neuropsychopharmacology 2020;45:104–20. 10.1038/s41386-019-0478-5.

- 42. Espeland MA, Gaussoin SA, Bahnson J, et al Impact of an 8‐Year Intensive Lifestyle Intervention on an Index of Multimorbidity. J Am Geriatr Soc 2020;68:2249–56. 10.1111/jgs.16672.

- 43. Vartiainen E. The North Karelia Project: Cardiovascular disease prevention in Finland. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract 2018;2018, 10.21542/gcsp.2018.13.

- 44. American College of Lifestyle Medicine in 2025. Health Equity Achieved Through Lifestyle Medicine. https://lifestylemedicine.org/heal-initiative/ (15 March 2025, date last accessed).

- 45. Slattery P, Saeri AK, Bragge P. Research co-design in health: A rapid overview of reviews. Health Res Policy Syst 2020;18:1–13. 10.1186/s12961-020-0528-9.

- 46. Parker LJ, Marx KA, Nkimbeng M, et al It’s More Than Language: Cultural Adaptation of a Proven Dementia Care Intervention for Hispanic/Latino Caregivers. Gerontologist 2023;63:558–67. 10.1093/geront/gnac120.

- 47. Weiss CC, Purciel M, Bader M, et al Reconsidering Access: Park Facilities and Neighborhood Disamenities in New York City. Journal of Urban Health 2011;88:297–310. 10.1007/s11524-011-9551-z.

- 48. Chudyk AM, McKay HA, Winters M, et al. Neighborhood walkability, physical activity, and walking for transportation: A cross-sectional study of older adults living on low income. BMC Geriatr 2017;17:1–14. 10.1186/s12877-017-0469-5

- 49. Gibbs JC, McArthur C, Milligan J, et al Measuring the Implementation of Lifestyle-Integrated Functional Exercise in Primary Care for Older Adults: Results of a Feasibility Study. Can J Aging 2019;38:350–66. 10.1017/S0714980818000739.

- 50. World Health Organization in 2023. National programmes for age-friendly cities and communities: a guide. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240068698 (10 March 2025, date last accessed).

- 51. Wingood GM, DiClemente RJ. The ADAPT-ITT Model. JAIDS 2008;47:S40–6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1.

- 52. Collins LM, Murphy SA, Strecher V. The Multiphase Optimization Strategy (MOST) and the Sequential Multiple Assignment Randomized Trial (SMART): New Methods for More Potent eHealth Interventions. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:S112–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.022.

- 53. Persaud A, Smith NR, Lindros J, et al Assessing the market viability of a packaged intensive health behavior and lifestyle treatment. Transl Behav Med 2023;13:903–8. 10.1093/tbm/ibad074.