Purpose

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) has become one of the world’s most serious public health challenges in recent years. According to the United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), there were 37.9 million people globally living with HIV in 2018, which was 3.3% higher than 2015. In 2022, about 39 million people globally had HIV, including 37.5 million adults and 1.5 million children (<15 years). Women and girls made up 53%. While 86% of people with HIV knew their status, 14% (5.5 million) still required testing services. Globally 46% of all new HIV infections were among women and girls in 2022. HIV testing is an essential gateway to HIV prevention, treatment, care, and support services. The global target for HIV status awareness is 95% by 2025. Asia ranks second only to sub-Saharan Africa in terms of the number of people living with HIV. The United Nations (UN) has set a Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) target to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030. Thailand stands out as one of the most severely affected countries in the Asia-Pacific region regarding HIV prevalence, with 1% of adults aged 15 to 49 living with HIV in 2020, compared to less than 0.1% in neighbouring countries like Bangladesh, Mongolia, New Zealand, and Sri Lanka.,, Thailand is one of the Asian countries that have been most impacted by the epidemic of HIV/AIDS., Regardless of continuous widespread international efforts, the epidemic of HIV/AIDS has survived more than 4 decades with higher prevalence in low and middle income countries (LMIC), and still remains a threat to millions of lives and destabilizes the development of the vulnerable countries.- Specifically, Thailand has made notable progress through prevention programs but continue to face significant challenge, with over 440 000 people living with HIV and thousands of deaths due to HIV annually.

The 2016 UNAIDS political declaration aimed to reduce new HIV infections to under 500 000 globally by 2020. A key target was ensuring 90% of young people had the knowledge, skills, and access to sexual and reproductive health services to protect themselves, reducing new infections among adolescent girls and young women to under 100 000 annually. One of the key indicators for achieving Sustainable Development Goal 3 (SDG3), set by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2015 is to end AIDS as a public health threat by 2030., However, the current trend suggests otherwise.- HIV remains a significant public health issue in Thailand despite the successful preventions in the early to mid-1990s and the expansion of access to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in the 2000s. Data from the HIV sentinel surveillance system (HSS) and surveys among key affected populations and the general population suggest the continued spread of HIV and ongoing risk behaviours.

Misconceptions are a significant barrier to controlling the spread of AIDS. They contribute to negative attitudes towards those affected by the disease, potentially causing serious harm to both their physical and emotional well-being. Providing accurate information about HIV/AIDS is the first step towards raising awareness among the general public, which in turn can help people protect themselves from HIV infection. This strategy aligns with the Global AIDS Monitoring (GAM) reporting indicator provided by UNAIDS, which has shown that the percentage of young people who have comprehensive and correct knowledge of HIV prevention and transmission, is defined as (1) knowing that consistent use of a condom during sexual intercourse and having just 1 uninfected faithful partner can reduce the chance of getting HIV, (2) knowing that a healthy-looking person can have HIV, and (3) rejecting the 2 most common local misconceptions about transmission/prevention of HIV/AIDS. HIV/AIDS related knowledge and education are seen by many as central to increasing people’s awareness of, as well as decreasing their vulnerability to HIV/AIDS.- Previous studies have shown that the prevalence of HIV/AIDS is significantly higher among individuals who are unaware of the potential routes of transmission due to lack of sexual education.-

Studies suggest there are many potential factors that are attributable to the increased risk of HIV/AIDS infection and/or transmission. Such factors include sexual education, education, poverty, place of residence (urban/rural), gender inequity, migration, knowledge about HIV/AIDS, ethicality and exposure to media.,- Studies have found that sexual education has a significant positive effect on knowledge and attitudes about HIV and its transmission.,- Women from male-headed households often have less knowledge about HIV/AIDS and a greater belief in myths and misconceptions. This may be due to gender inequality, as women in male-headed households often have less freedom to participate in adult health education and are subjected to societal subordination, which influences the societal response to female drug users.,,, Evidence indicates that the primary modes of HIV/AIDS transmission include unprotected sexual contact, intravenous drug use with contaminated needles, blood transfusions, and vertical transmission from mother to child. However, there remains significant misconception about how HIV/AIDS is transmitted.

Several studies have examined HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitudes, and misconceptions among women in Asia, including Thailand. However, research on how sexual education and educational status affect HIV/AIDS awareness and misconceptions, using path analysis and socio-demographic mediators, is lacking. Such insights could guide interventions to achieve SDG3 by 2030. Identifying vulnerable cohorts at risk of HIV is crucial for efforts in prevention, treatment, care, and support. Therefore, this study aimed to conduct a path analysis using structural equation modelling to examine the complex associations between sexual education, educational status, and women’s knowledge about HIV/AIDS (awareness), transmission, and misconceptions, while investigating the mediating factors and identifying the most vulnerable group of women in Thailand.

Theoretical Framework

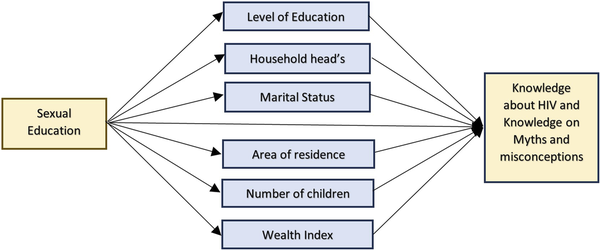

Various theories and models have been used in health communication campaigns to assess changes in behaviour, particularly regarding HIV/AIDS. Early in the pandemic, approaches based on the Health Belief Model (HBM), Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA), and AIDS Risk Reduction Model (ARRM) were prevalent. These models emphasize knowledge and behaviour in minimizing HIV/AIDS risk. The current study’s framework is based on HBM, positing that individual actions are influenced by perceived threat and benefits of addressing the disease., According to the HBM, it is hypothesized that in order to adopt recommended health behaviors, individuals must be aware of the potential negative outcomes, such as understanding how HIV/AIDS is transmitted and the methods of its prevention.- This model has been used in previous studies on HIV/AIDS prevention to address knowledge about HIV/AIDS, transmission methods, and related myths and facts. This study aims to examine how women’s perceptions of HIV/AIDS in Thailand are influenced by their knowledge of sexual education and various socio-demographic factors, such as level of education, area of residence, number of children, household wealth index, and marital status, by evaluating MICS data. In line with these objectives, the theoretical framework of the HBM was adopted for this study (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Conceptual framework illustrating the inter-relationships among key factors influencing knowledge about HIV and Knowledge on myths and misconceptions among women in Thailand.

Methods

Design

This study used secondary data from the latest Thailand Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey (MICS) conducted in 2022. It is a cross-sectional, population-based survey of Thai women aged 15-49, carried out from June 2022 to October 2022 using a multistage, stratified cluster sampling technique. As part of the Global MICS Programme, this survey was jointly conducted by the National Statistical Office of Thailand (NSOT) and the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). The sample size estimation and sampling method were designed to provide national-level estimates for a range of public health indicators concerning children and women, covering five regions and 12 priority provinces.

Households were selected through a two-stage process: first by region, then stratified by area type (urban/rural). Primary sampling units (PSUs) were chosen using probability proportional to size. Each region’s clusters were determined based on sample size, with 20 households randomly selected per PSU. After listing households in the selected areas, a systematic sample of 20 households was drawn for each PSU. The survey covered 1727 PSUs and 34 540 households. Detailed sampling design and MICS questionnaires are available at https://mics.unicef.org.

Sample

This study focused on a subset of the Thailand MICS dataset, including 3671 women aged 15-49 years.

Measures

Women’s knowledge about HIV and knowledge of HIV transmission and its misconceptions was considered as the main endogenous (outcome) variable in this study. This variable was determined by combining 2 sets of HIV-related questions. The first set assessed knowledge about HIV/AIDS transmission, with 2 questions asking whether women knew they could protect themselves from getting HIV/AIDS by: (i) having just 1 uninfected sex partner who has no other sex partners, and (ii) using a condom every time they have sex. The second set quantified knowledge on myths and misconceptions about HIV/AIDS based on responses to 4 questions: (i) Can people get HIV from mosquito bites? (ii) Can people get HIV by sharing food with a person who has HIV? (iii) Can people get HIV because of witchcraft or other supernatural means? and (iv) Is it possible for a healthy-looking person to have HIV? Answers to all 6 questions were combined into a binary variable, coded ‘yes’ = 1 if a respondent correctly answered all 6 questions and ‘no’ = 0 otherwise, based on similar past studies.,,

The exogenous variables (predictors) included: women’s exposure to sexual education (yes, no), education levels of both women and their household head (primary or lower secondary, upper secondary, higher), age (in years), area of residence (urban, rural), household wealth index (poorest, second, middle, fourth, richest), marital status (married, single, living together), number of children (no children, 1 or more children), gender of household head (male, female), and age of household head (15-35, 36-50, more than 50 years), which were selected based on the objective of the current research and suggested by previous research.,,

Analysis

The dataset used for this study included 3671 women from the 2022 Thailand MICS. Missing data were excluded in a list-wise manner, assuming they were missing at random., After descriptive analysis, a bivariate analysis was performed, tabulating HIV/AIDS knowledge across variables like age, residence, education (women and household head), wealth index, marital status, number of children, and exposure to sexual education. Associations were tested using Pearson Chi-square and t-tests.

In the Structural Equation Model (SEM), linear relationships between exogenous variables and knowledge about HIV are described, allowing simultaneous testing of several interrelationships, including mediation effects. Using mediation analysis as a guiding framework, SEM was employed to analyse the complex relationships between sexual education, several socio-demographic variables related to women and their households, and knowledge about HIV among Thai women.

Pathway selection and variable inclusion/exclusion were based on prior research and refined iteratively using standardized residuals and modification indices. Model fit was assessed using recommended indices, including a root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) below 0.07 and a comparative fit index (CFI) or Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) greater than 0.95. The significance of the mediation effect was assessed based on a bootstrap analysis of 5000 samples. Data preparation and statistical analysis were conducted using R (version 4.2.0) and SPSS (version 29).

Results

In the MICS 2022 survey, data from 3671 Thai women were available for analysis. The women in this study had a mean age of 19.61 years (SD = 3.01). About 51.1% of the women lived in urban areas, while the rest lived in rural areas. A significant portion (47.5%) of the women had completed upper secondary education, 26.6% had completed primary or lower secondary education, and 25.9% had reached higher education. More than half (66.1%) of the women were single, while 9.9% were married and 24% lived together with a partner. Approximately 71% of women did not have children, and most households (52.6%) were headed by males. Approximately 70% of the household heads had completed only primary or lower secondary education, and the majority were over the age of 50 years. Most of the women (91%) had received sexual education. Supplemental Table 1 provides a detailed breakdown of sociodemographic variables (Suppplemental Table 1).

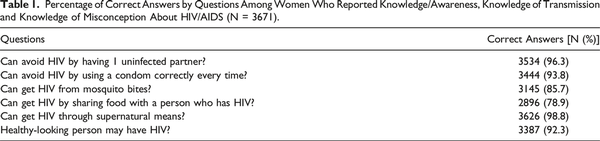

Each of the 6 questions was answered accurately most of the time (78.9-98.8%) (Table 1). However, only 62% of respondents answered all 6 questions correctly.

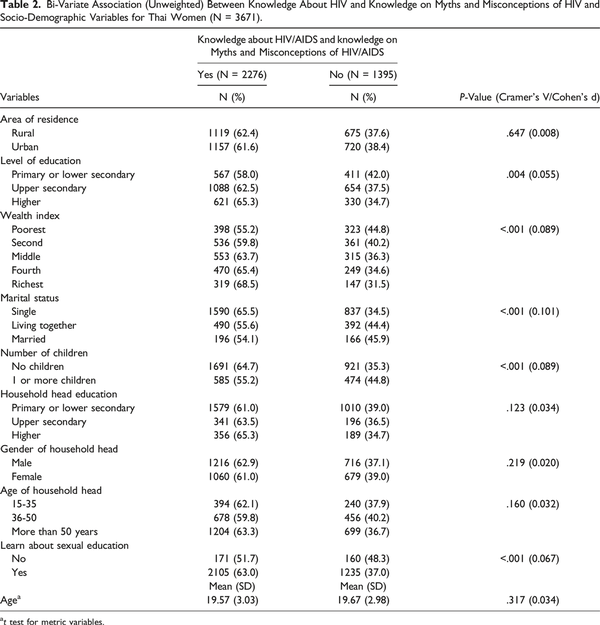

Table 2 presents the unweighted bivariate association between women’s knowledge about HIV and various socio-demographic factors. Several Chi-square tests of independence were performed to examine the relationships between knowledge about HIV/AIDS and categorical socio-demographic variables. The results reveal that women’s knowledge of HIV is significantly associated with several variables, including their level of education (X2(2) = 11.273, P = .004), wealth index (X2(4) = 28.846, P < .001), marital status (X2(2) = 37.744, P < .001), number of children (X2(1) = 28.857, P < .001), and knowledge of sexual education (X2(1) = 16.502, P < .001). Based on the values of Cramer’s V, marital status, wealth index, and the number of children show a strong association with women’s knowledge of HIV/AIDS (Table 2).

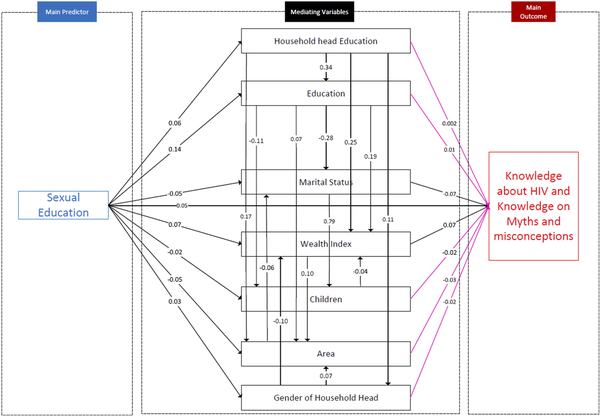

Figure 2

Fitted structural equation model (SEM) illustrating the relationship between women’s sexual education status, various socio-demographic factors, and their Knowledge about HIV/AIDS and knowledge on myths and misconceptions about HIV/AIDS (N = 3671).

Socio-demographic factors, such as women’s and the household head’s education, marital status, wealth index, number of children, area of residence, and gender of household head, have been integrated as mediators in the SEM, with pathways outlined in line with earlier research. Variables not associated with women’s knowledge of HIV, such as age and the age of the household head, were excluded from the SEM. Figure 2 shows the path diagram of the final adjusted fitted SEM. The main predictor in our model is sexual education, which influences the outcome variable, knowledge about HIV/AIDS and its transmission and misconception, through several mediating variables. Notably, the model fit statistics ( RMSEA = 0.024, CFI = 0.998, TLI = 0.988, SRMR = 0.011) show an excellent fit to the data.

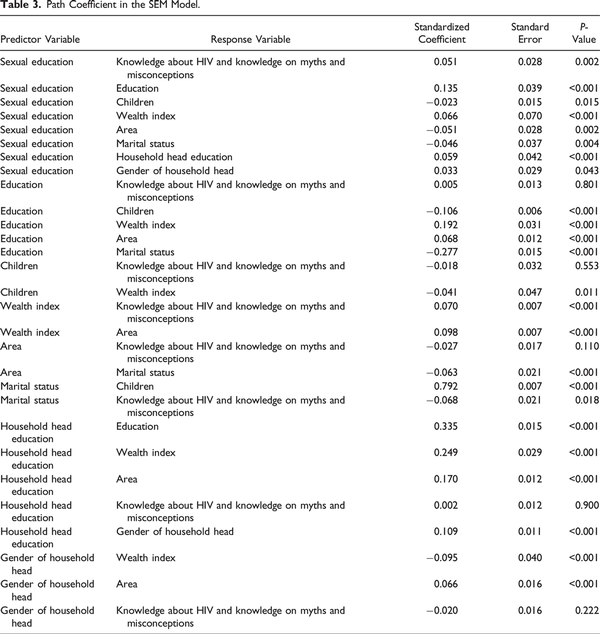

Table 3 summarizes the final adjusted SEM, showing path coefficients and P-values for the direct and indirect effects on women’s HIV knowledge. Sexual education (β = 0.051) and higher household wealth (β = 0.070) positively impact HIV knowledge and misconceptions. In contrast, marital status (β = −0.068) is negatively associated, indicating that married women are less likely to have accurate knowledge about HIV/AIDS and its transmission.

Sexual education is positively linked to education level (β = 0.135), wealth index (β = 0.066), household head’s education (β = 0.059), and female-headed households (β = 0.033). Women receiving sexual education tend to have higher education, wealth, and educated household heads. Conversely, sexual education is negatively associated with number of children (β = −0.023), urban residence (β = −0.051), and marital status (β = −0.046), indicating women without it are more likely married with more children and living in urban areas.

Women’s education is positively linked to household wealth index (β = 0.192) and area of residence (β = 0.068), while negatively associated with the number of children (β = −0.106) and marital status (β = −0.277). This indicates that more educated women tend to have fewer children and are more likely to be single. The education level of the household head positively correlates with women’s education (β = 0.335), wealth index (β = 0.249), urban residence (β = 0.170), and female-headed households (β = 0.109). This suggests that higher household head education leads to better educational opportunities for women, increased wealth, and a tendency to live in urban areas. Women’s area of residence negatively associates with marital status (β = −0.063), indicating urban living is linked to being single. The gender of the household head negatively correlates with wealth index (β = −0.095), while positively associating with urban residence (β = 0.066).

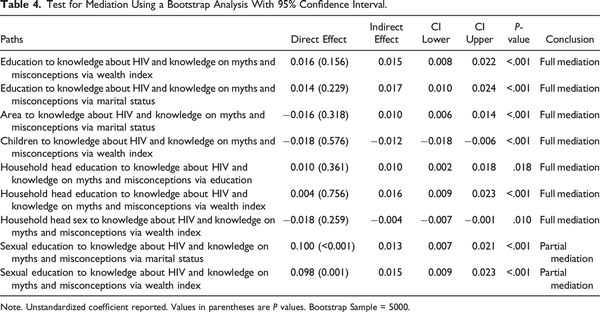

As shown in Table 4, the final SEM model reveals significant indirect effects based on bootstrap analysis. Figure 2 illustrates several full mediations between women’s sexual education and their knowledge about HIV/AIDS. The relationship between women’s education and HIV knowledge is fully mediated by household wealth and marital status. Household wealth also mediates the links between number of children, household head’s education, gender of the household head, and HIV knowledge/misconceptions. Additionally, women’s marital status fully mediates the relationship between area of residence and HIV knowledge/misconceptions. Similarly, the relationship between household head’s education and HIV knowledge/misconceptions is fully mediated by women’s education level. Significant partial mediations were also identified, particularly the relationships between sexual education and knowledge and misconceptions on HIV/AIDS through marital status and wealth index (Table 4 and Figure 2). Supplemental document (Table 2) shows details other partial mediations.

Discussion

In this study, data from the latest nationally representative MICS conducted in 2022 were analyzed to identify predictors of poor HIV/AIDs transmission among women living in Thailand. This study estimate the portion of women who were vs were not knowledgeable about HIV/AIDS transmission, and examined the direct and indirect associations of knowledge status with sociodemographic factors through SEM analysis. The findings demonstrated strong evidence of direct, indirect, and mediating effects of women’s sexual education and education status on knowledge about HIV/AIDS. The results revealed that overall, 62% of Thai women reported having accurate knowledge about HIV. Poor knowledge was more likely for women without sexual education, living in households led by an illiterate head, residing in rural areas, belonging to the poorest wealth quintile, and having a low level of education.

These findings are consistent with previous literature.,, As anticipated, consistent with previous studies and the Health Belief Model (HBM), this study found that several sociodemographic factors—including education level, wealth index, living area, gender of the household head, number of children, and marital status—mediated the relationship between the primary predictor, sexual education, and knowledge about HIV/AIDS.-

This study reveals that women’s sexual education, wealth index, and marital status significantly impact HIV/AIDS knowledge, supporting previous research that highlights these sociodemographic factors as key predictors.-,, As expected, sexual education and education are the key drivers in the knowledge of HIV/AIDs in women, as educated women are expected to be more concerned about their health and their newborn child as compared to their uneducated counterparts.,, As addressed in past literature, it is expected that women with institutional education would understand the concept of how a virus spreads, comprehend the deadliness of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) and so render awareness.,, Studies have emphasised that to reduce the risk of infection among young women, the most important thing is to promote comprehensive sexual education., The structural equation model reveals that sexual education directly improves knowledge of HIV/AIDS and its misconceptions. Women’s education impacts HIV knowledge, fully mediated by household wealth and marital status. To enhance HIV/AIDS knowledge, it’s crucial to educate women and provide sexual education, considering factors like wealth, marital status, and area of residence.

Studies have highlighted that married women are more likely to be exposed to misconceptions about HIV/AIDS transmission compared to never-married women, as observed in this study of married women in Thailand., Similarly, married women are at a higher risk of HIV/AIDS due to a range of structural barriers and contextual gender inequalities, including poverty, economic disempowerment, cultural inequities, increased risk of sexual violence, gender power imbalances in sexual interactions, and traditional beliefs about HIV/AIDS knowledge and its transmission., Misconceptions about HIV/AIDS transmission and a lack of knowledge about the disease were found to be less prevalent among women in rural areas compared to those in urban areas. This finding is consistent with other studies conducted in China, Malawi, Ghana, and Bangladesh,,,,, possibly due to inhabitants of these regions possessing limited information about how HIV/AIDS is transmitted. However, rural women were less likely to believe that HIV/AIDS could be transmitted through witchcraft or supernatural means, a result that warrants further investigation using qualitative data.

While the household head’s education did not directly affect women’s HIV/AIDS knowledge, its impact was fully mediated by the women’s education level. Women in households where the head had primary or higher education showed significantly greater HIV/AIDS knowledge, supporting previous research that views education as a “social vaccine” against HIV/AIDS.

Educated women are more likely to live in urban areas and be wealthier, yet their ability to identify HIV myths and misconceptions is indirectly influenced. Sexual education significantly correlates with the wealth index, which indirectly affects knowledge about HIV/AIDS myths, aligning with previous studies., As hypothesized in the conceptual framework, the effects of sexual education on knowledge and understanding of myths and misconceptions about HIV/AIDS was mediated through women’s wealth index. This study found that respondents in the richest quintile had better knowledge and understanding of myths and misconceptions about HIV/AIDS than respondents in the poorest quintile. A possible explanation is that HIV/AIDS is considered a disease of the poor. Poverty increases risky behaviour towards HIV/AIDS such as transactional gender. Poverty also leads to fewer opportunities for work and education. On a broader scale, financial shortfalls can limit educational opportunities, access to health care, and access to jobs. These conditions create a favourable environment for the spread of HIV/AIDS.,

In summary, this study found that education and sexual education were important predictors of knowledge about HIV/AIDS. Improvement in education and sexual education are likely to assist Thai women to be better informed about HIV transmission, which in turn is likely to reduce new cases of HIV/AIDS, consistent with the SDG goal.,-

To our knowledge, this is the first study to utilize the most recent MICS (2022) data—a relatively large and representative dataset—to assess the direct and indirect impact of sexual education and educational attainment on HIV/AIDS knowledge and awareness among Thai women, using path analysis through an SEM approach. However, this study had several limitations. First, the HIV/AIDS data from the MICS were based on self-reported information, which may be subject to recall bias. Second, the responses regarding HIV/AIDS knowledge, transmission, and misconceptions were dichotomous, such a binary approach may have oversimplified knowledge status, and that by a continuous measure of knowledge may be a better indicator of knowledge of HIV/AIDS. Third, women who had never heard of HIV/AIDS were not asked about transmission or misconceptions, significantly reducing the sample size in the latter part of the analysis, which requires careful interpretation. Fourth, since the MICS surveys are cross-sectional, causal associations cannot be established. Fifth, although women’s education was assessed, health literacy could not be evaluated due to limitations in the survey data, which might be more relevant for understanding health awareness. Sixth, due to the absence of qualitative data, the generalization of the findings should be approached with caution. Finally, women’s empowerment and media exposure were not included in the analysis due to limitations in data availability. Future studies or surveys could consider addressing this issue.

To enhance knowledge and address misconceptions about HIV/AIDS transmission among married women in Thailand, policymakers should consider implementing effective intervention programs that focus on factors indirectly influencing HIV/AIDS awareness, rather than relying solely on sexual education and/or education. Strengthening educational initiatives alongside sexual education could play a crucial role in fostering knowledge and awareness among the younger generation. Additionally, health promotion and gender equality programs involving community participation could be highly effective in Thailand, where women’s autonomy remains limited. Moreover, the government plays a crucial role in reducing stigmatizing attitudes toward HIV/AIDS transmission by promoting accurate information and fostering understanding among youth through partnerships with health professionals and public figures.

Future research should adopt a more in-depth approach using a mixed-methods study design at the population level, incorporating mediating factors alongside the primary predictors of HIV/AIDS knowledge. Additionally, studies should emphasize a co-design approach by involving community members in the research design process.

Conclusions

In the dynamic social settings of LMICs including Thailand, it is necessary to gather vital evidence through mixed-method research to empower women with sexual education along with education, alongside achieving broader goals including the SDG3 by 2030. The direct and indirect effect of sexual education, education, residence, wealth index and husband’s education on knowledge and understanding of myths and misconceptions about HIV/AIDS outline the complex mechanisms of various sociodemographic factors on Thai women’s knowledge about HIV/AIDS. In summary, this study’s findings support previous studies examining the influences of sociodemographic characteristics on knowledge and understanding of myths and misconceptions about HIV/AIDS. The findings indicated that there were multifaceted scopes for improvement in increasing awareness about HIV/AIDS and clarifying misconceptions regarding the mode of transmission of HIV/AIDS through a path analysis approach. Strengthening educational programs along with sexual education could have great importance in fostering knowledge and awareness among the younger generation.

So What?

What is Already Known on this Study?

The issue of HIV/AIDS remains a major public health concern, knowledge about HIV/AIDS and its misconceptions about transmission continue to hinder prevention efforts. Although sexual education has been identified as a key element in improving awareness about HIV/AIDS, other sociodemographic factors can also influence its effectiveness.

What Does this Article Add?

There is a significant direct and indirect association between sexual education, wealth index, level of education, and marital status on HIV knowledge and misconceptions among women in Thailand. Therefore, enhancing HIV awareness necessitates addressing both of these interconnected sociodemographic factors through a path analysis model, rather than concentrating exclusively on sexual education or general education.

What are the Implications for Health Promotion Practice or Research?

To achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goal of reducing HIV/AIDS transmission by 2030, policymakers must implement multifaceted interventions that enhance access to both formal education and sexual education. Health systems in LMICs need to prioritize education-based interventions to address HIV/AIDS knowledge gaps, while considering the broader socioeconomic context. This integrated approach can reduce health disparities and improve HIV prevention efforts, leading to more effective and sustainable outcomes in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the National Statistical Office of Thailand (NSO) for conducting Thailand MICS as part of the Global MICS programme, with government funding and financial support of UNICEF.

Authors’ Contributions This study was conceptualized by J.B. The study design was developed by J.B., while the screening and analysis of the data were performed by L.G., J.B., and P.A. The initial draft of the manuscript was prepared by J.B. S.B., L.G., P.A. and U.B. thoroughly reviewed the draft manuscript and provided their feedback. The final manuscript was read and approved by all the authors.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. UNAIDS. Global AIDS update 2019 - Communities at the centre. 2019. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2019/2019-global-AIDS-update. Accessed 12 July 2024.

- 2. UNAIDS. Global HIV & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet. 2022. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheet. Accessed 12 July 2024.

- 3. OECD, Organization WH. HIV/AIDS. 2022.

- 4. The Global Economy. HIV infections - country ranking. 2024. https://www.theglobaleconomy.com/rankings/HIV_infections/South-East-Asia/. Accessed 12 October 2024.

- 5. Liamputtong P, Haritavorn N, Kiatying-Angsulee N. Living positively: the experiences of Thai women living with HIV/AIDS in Central Thailand. Qual Health Res. 2011;22(4):441–451. doi:10.1177/1049732311421680

- 6. Shafik N, Deeb S, Srithanaviboonchai K, et al. Awareness and attitudes toward HIV self-testing in Northern Thailand. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(3):852. doi:10.3390/ijerph18030852

- 7. Bekker LG, Alleyne G, Baral S, et al. Advancing global health and strengthening the HIV response in the era of the sustainable development goals: the international AIDS society-lancet commission. Lancet. 2018;392(10144):312–358. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(18)31070-5

- 8. Harries AD, Suthar AB, Takarinda KC, et al. Ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic in low- and middle-income countries by 2030: is it possible? F1000Res. 2016;5:2328. doi:10.12688/f1000research.9247.1

- 9. Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Danhoundo G, Shah V, Ekholuenetale M. Trends and determinants of HIV/AIDS knowledge among women in Bangladesh. BMC Publ Health. 2016;16:812.

- 10. Muccini C, Crowell TA, Kroon E, et al. Leveraging early HIV diagnosis and treatment in Thailand to conduct HIV cure research. AIDS Res Ther. 2019;16(1):25. doi:10.1186/s12981-019-0240-4

- 11. Declaration and AIDS. Global AIDS monitoring 2020. 2020. https://indicatorregistry.unaids.org/sites/default/files/global-aids-monitoring_en.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2024.

- 12. Work of the statistical commission pertaining to the 2030 agenda for sustainable development (A/RES/71/313). 1-25, 2017.

- 13. UNAIDS. UNAIDS global AIDS update 2022. 2022. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2022-global-aids-update-summary_en.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2024.

- 14. Jamieson D, Kellerman SE. The 90 90 90 strategy to end the HIV Pandemic by 2030: can the supply chain handle it? J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20917.

- 15. Stover J, Bollinger L, Izazola JA, et al. What is required to end the AIDS epidemic as a public health threat by 2030? The cost and impact of the fast-track approach. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0154893. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0154893

- 16. UNAIDS. Fast-track - Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030. 2014. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/JC2686_WAD2014report. Accessed 12 July 2024.

- 17. Thailand Working Group on HIV/AIDS Projections. Projection of HIV/AIDS in Thailand 2010-2030. 2015. https://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/resource/projection-hiv-aids-thailand-2010-2030.pdf. Accessed 12 July 2024.

- 18. Seid A, Ahmed M. What are the determinants of misconception about HIV transmission among ever-married women in Ethiopia? HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2020;12:441–448. doi:10.2147/hiv.S274650

- 19. Bhowmik J, Biswas RK. Knowledge about HIV/AIDS and its transmission and misconception among women in Bangladesh. Int J Health Policy Manag. 2022;11(11):2542–2551. doi:10.34172/ijhpm.2022.6321

- 20. Estifanos TM, Hui C, Tesfai AW, et al. Predictors of HIV/AIDS comprehensive knowledge and acceptance attitude towards people living with HIV/AIDS among unmarried young females in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health. 2021;21(1):37. doi:10.1186/s12905-021-01176-w

- 21. Haque MA, Hossain MSN, Chowdhury MAB, Uddin MJ. Factors associated with knowledge and awareness of HIV/AIDS among married women in Bangladesh: evidence from a nationally representative survey. SAHARA-J. 2018;15(1):121–127. doi:10.1080/17290376.2018.1523022

- 22. Igulot P, Magadi MA. Socioeconomic status and vulnerability to HIV infection in Uganda: evidence from multilevel modelling of AIDS indicator survey data. AIDS Res Treat. 2018;2018(1):7812146. doi:10.1155/2018/7812146

- 23. Appiah-Agyekum NN, Suapim RH. Knowledge and awareness of HIV/AIDS among high school girls in Ghana. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2013;5:137–144. doi:10.2147/hiv.S44735

- 24. de Jesus LAO, Martinez MCO. Knowledge and awareness on HIV/AIDS of senior high school students towards an enhanced reproductive health education program. LIFE: Int J Health Life-Sci. 2019;5:01–20.

- 25. Frances EO, Akua AA, Christian A, Abubakar AR, Victoria DA, Esther O. Knowledge and sexual behaviors: a path towards HIV/AIDS prevention among university students. Afr J Reprod Health. 2023;27(9):117–126. doi:10.29063/ajrh2023/v27i9.12

- 26. World Health Organization. HIV and AIDS. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids

- 27. Gazi R, Mercer A, Wansom T, Kabir H, Saha N, Azim T. An assessment of vulnerability to HIV infection of boatmen in Teknaf, Bangladesh. Confl Health. 2008;2:5. doi:10.1186/1752-1505-2-5

- 28. Hossain M, Mani KKC, Sidik SM, Shahar HK, Islam R. Knowledge and awareness about STDs among women in Bangladesh. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):775. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-14-775

- 29. Yaya S, Bishwajit G, Danhoundo G, Seydou I. Extent of knowledge about HIV and its determinants among men in Bangladesh. Front Public Health. 2016;4:246. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00246

- 30. Sheikh MT, Uddin MN, Khan JR. A comprehensive analysis of trends and determinants of HIV/AIDS knowledge among the Bangladeshi women based on Bangladesh Demographic and Health Surveys, 2007–2014. Arch Public Health. 2017;75(1):59. doi:10.1186/s13690-017-0228-2

- 31. Iqbal S, Maqsood S, Zafar A, Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. Determinants of overall knowledge of and attitudes towards HIV/AIDS transmission among ever-married women in Pakistan: evidence from the Demographic and Health Survey 2012–13. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):793. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7124-3

- 32. Son N, Luan H, Tuan H, Cuong L, Duong NTT, Kien VD. Trends and factors associated with comprehensive knowledge about HIV among women in Vietnam. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2020;5:91. doi:10.3390/tropicalmed5020091

- 33. Chi X, Hawk ST, Winter S, Meeus W. The effect of comprehensive sexual education program on sexual health knowledge and sexual attitude among college students in Southwest China. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2015;27(2):Np2049–Np2066. doi:10.1177/1010539513475655

- 34. Tu F, Yang R, Li R, et al. Structural equation model analysis of HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitude, and sex education among freshmen in Jiangsu, China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:892422. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.892422

- 35. Center for Health Policy Studies MU. Review of comprehensive sexuality education in Thailand. 2016. https://www.unicef.org/thailand/sites/unicef.org.thailand/files/2018-08/comprehensive_sexuality_educationEN.pdf. Accessed 25 August 2024.

- 36. Fladseth K, Gafos M, Newell ML, McGrath N. The impact of gender norms on condom use among HIV-positive adults in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0122671. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0122671

- 37. Durongrittichai V. Knowledge, attitudes, self-awareness, and factors affecting HIV/AIDS prevention among Thai university students. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2012;43:1502–1511.

- 38. Mondal MN, Hoque N, Chowdhury MR, Hossain MS. Factors associated with misconceptions about HIV transmission among ever-married women in Bangladesh. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2015;68(1):13–19. doi:10.7883/yoken.JJID.2013.323

- 39. Letamo G. Misconceptions about HIV prevention and transmission in Botswana. Afr J AIDS Res. 2007;6(2):193–198. doi:10.2989/16085900709490414

- 40. Glanz K, Rimer BK. [W1] glance theory. Health San Francisco. 2005;83(21):13–14. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.21.9532

- 41. Zainiddinov H, Habibov N. Trends and predictors of knowledge about HIV/AIDS and its prevention and transmission methods among women in Tajikistan. Eur J Public Health. 2016;26(6):1075–1079. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckw077

- 42. Petosa R, Wessinger J. Using the health belief model to assess the HIV education needs of junior and senior high school students. Int Q Community Health Educ. 1989;10(2):135–143. doi:10.2190/2M88-72L9-Q7XY-XE92

- 43. Petosa R, Wessinger J. The AIDS education needs of adolescents: a theory-based approach. AIDS Educ Prev. 1990;2(2):127–136.

- 44. National Statistical Office of Thailand. Thailand Multiple Indicator Cluster Survey 2022, Survey Findings Report; 2023. https://www.unicef.org/thailand/reports/thailand-multiple-indicator-cluster-survey-2022

- 45. Teshale AB, Yeshaw Y, Alem AZ, et al. Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS and associated factors among women of reproductive age in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis using the most recent demographic and health survey of each country. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22(1):130. doi:10.1186/s12879-022-07124-9

- 46. Bhowmik J, Biswas RK, Ananna N. Women’s education and coverage of skilled birth attendance: an assessment of sustainable development goal 3.1 in the South and Southeast Asian region. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0231489. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0231489

- 47. Gamage S, Biswas RK, Bhowmik J. Health awareness and skilled birth attendance: an assessment of sustainable development goal 3.1 in south and south-east Asia. Midwifery. 2022;115:103480. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2022.103480

- 48. Adelson JL. Examining relationships and effects in gifted education research: an introduction to structural equation modeling. Gifted Child Quarterly. 2011;56(1):47–55. doi:10.1177/0016986211424132

- 49. Hu L-T, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model. 1999;6(1):1–55. doi:10.1080/10705519909540118

- 50. Sherafat-Kazemzadeh R, Gaumer G, Hariharan D, Sombrio A, Nandakumar A. Between a rock and a hard place: how poverty and lack of agency affect HIV risk behaviors among married women in 25 African countries: a cross-sectional study. J Glob Health. 2021;11:04059. doi:10.7189/jogh.11.04059

- 51. UN. Lack of access to sexual, reproductive health education and rights results in harmful practices, impedes sustainable development, speakers tell population commission. United Nations. https://press.un.org/en/2023/pop1106.doc.htm

- 52. Tu F, Yang R, Li R, et al. Structural equation model analysis of HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitude, and sex education among freshmen in Jiangsu, China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:892422. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2022.892422

- 53. Stahlman S, Liestman B, Ketende S, et al. Characterizing the HIV risks and potential pathways to HIV infection among transgender women in Côte d’Ivoire, Togo and Burkina Faso. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(3 Suppl 2):20774. doi:10.7448/ias.19.3.20774

- 54. Thurman TR, Nice J, Visser M, Luckett BG. Pathways to sexual health communication between adolescent girls and their female caregivers participating in a structured HIV prevention intervention in South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2020;260:113168. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113168

- 55. Loncar D, Izazola-Licea JA, Krishnakumar J. Exploring relationships between HIV programme outcomes and the societal enabling environment: a structural equation modeling statistical analysis in 138 low- and middle-income countries. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2023;3(5):e0001864. doi:10.1371/journal.pgph.0001864

- 56. Shimamoto K, Gipson JD. Investigating pathways linking women’s status and empowerment to skilled attendance at birth in Tanzania: a structural equation modeling approach. PLoS One. 2019;14(2):e0212038. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0212038

- 57. Zhang T, Miao Y, Li L, Bian Y. Awareness of HIV/AIDS and its routes of transmission as well as access to health knowledge among rural residents in Western China: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1630. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-7992-6

- 58. Gebreslassie H, Gebremedhin H, Alemayehu M, Fesseha G. Knowledge and misconception on HIV/AIDS and associated factors among primary school students within the window of opportunity in Mekelle city, North Ethiopia. Int J Adv Sci Res. 2018;5:831.

- 59. Swenson RR, Rizzo CJ, Brown LK, et al. HIV knowledge and its contribution to sexual health behaviors of low-income African American adolescents. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(12):1173–1182. doi:10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30772-0

- 60. Diress GA, Ahmed M, Linger M. Factors associated with discriminatory attitudes towards people living with HIV among adult population in Ethiopia: analysis on Ethiopian demographic and health survey. Sahara J. 2020;17(1):38–44. doi:10.1080/17290376.2020.1857300

- 61. Tenkorang E. Women’s autonomy and intimate partner violence in Ghana. Int Perspect Sex Reprod Health. 2018;44:51–61. doi:10.1363/44e6118

- 62. Sano Y, Antabe R, Atuoye KN, et al. Persistent misconceptions about HIV transmission among males and females in Malawi. BMC Int Health Hum Rights. 2016;16(1):16. doi:10.1186/s12914-016-0089-8

- 63. Ahmed M, Seid A. Factors associated with premarital HIV testing among married women in Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2020;15(8):e0235830. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235830

- 64. Seid A, Ahmed M. What are the determinants of misconception about HIV transmission among ever-married women in Ethiopia? HIV/AIDS (Auckl). 2020;12:441–448.

- 65. Qian HZ, Wang N, Dong S, et al. Association of misconceptions about HIV transmission and discriminatory attitudes in rural China. AIDS Care. 2007;19(10):1283–1287. doi:10.1080/09540120701402814

- 66. Tenkorang EY. Myths and misconceptions about HIV transmission in Ghana: what are the drivers? Cult Health Sex. 2013;15(3):296–310. doi:10.1080/13691058.2012.752107

- 67. Rodrigo C, Rajapakse S. HIV, poverty and women. Int Health. 2010;2(1):9–16. doi:10.1016/j.inhe.2009.12.003

- 68. Suantari D. Misconceptions and stigma against people living with HIV/AIDS: a cross-sectional study from the 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Survey. Epidemiol Health. 2021;43:e2021094. doi:10.4178/epih.e2021094

- 69. Akuiyibo S, Anyanti J, Idogho O, et al. Impact of peer education on sexual health knowledge among adolescents and young persons in two North Western states of Nigeria. Reprod Health. 2021;18(1):204. doi:10.1186/s12978-021-01251-3

- 70. Gao X, Wu Y, Zhang Y, et al. Effectiveness of school-based education on HIV/AIDS knowledge, attitude, and behavior among secondary school students in Wuhan, China. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e44881. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0044881

- 71. Leekuan P, Kane R, Sukwong P, Kulnitichai W. Understanding sexual and reproductive health from the perspective of late adolescents in Northern Thailand: a phenomenological study. Reprod Health. 2022;19(1):230. doi:10.1186/s12978-022-01528-1