1 INTRODUCTION

Crohn's disease (CD) is an idiopathic, progressive inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) affecting potentially the entire gastrointestinal tract. Patients require anti‐inflammatory treatment and often surgery, in order to avoid long‐term bowel damage and disability. Perianal manifestation in patients with CD is common and have a negative impact on the patients' quality of life. Perianal fistulae and abscesses are the most common forms of perianal disease. The estimated rate of perianal disease among patients with CD varies widely across studies. Perianal disease was present in about 10%–15% of CD patients at the time of diagnosis in population‐based cohorts, and one out of five CD patients developed perianal fistula during follow‐up., , , A recent inception cohort from Denmark (2003–2004) found that 10% of the patients had perianal fistula or abscess at diagnosis. The Inflammatory Bowel Disease South‐Limburg (IBDSL) registry from the Netherlands is one of the largest available population‐based cohort, including 1162 CD patients diagnosed between 1991 and 2011. The cumulative probability of developing perianal fistula during the course of the disease was 8.3% after 1 year, 11.6% after 5 years and 15.8% after 10 years in this population‐based cohort. Results of a recent meta‐analysis identifying 12 population‐based studies showed that approximately 11.5% of the patients (95% CI: 6.7%–19.0%) had perianal disease at the time of CD diagnosis, and the overall prevalence of perianal disease was 18.7% (95% CI: 12.5%–27.0%) among these study populations.

Studies suggest that the presence of perianal disease is associated with severe disease course and it is a predictor for progression to complicated disease behaviour, surgeries and hospitalizations., , The introduction of biological therapies has changed the therapeutic landscape of CD significantly. Randomised controlled trials have shown that antitumor necrosis factor‐α (aTNF) therapies are effective in perianal disease,, nevertheless, medical treatment (in conjunction with minor perianal surgical interventions) alone is often insufficient to produce sustainable healing, and proctectomy is required in about 2%–20% of the cases.

Population‐based cohort studies looking into disease course and clinical outcomes among patients with perianal CD are rare, and even fewer are available from the era of biological therapies. The Veszprem IBD cohort is a well‐established, prospective population‐based inception cohort from Veszprem Province, Hungary, originally initiated in 1977. Recently, disease course, treatment strategy, resective and perianal surgery rates have been published from the Veszprem cohort, including incident patients from the ‘biological era’ (2007–2018). The present work provides the complete assessment of patients with perianal Crohn's disease from the Veszprem IBD cohort encompassing more than 40 years of follow‐up.

Our aim was to evaluate the burden of perianal disease among CD patients, analyse therapeutic strategy and need for perianal surgical intervention rates over multiple decades of different therapeutic eras. Furthermore, we evaluated disease phenotype progression and resective surgery rates in perianal CD patients in a prospective population‐based cohort from Hungary.

2 MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Study population and design

This study is based on a prospective population‐based inception cohort of CD patients from Veszprem Province, Hungary. Veszprem Province is an administrative region in western Hungary. The province consists of both industrial and agricultural regions. The number of permanent population was relatively stable, with a slight decrease from 386,462 to 376,211 souls from 1980 to 1998. The rate of Gypsies is around 2.5%, few Jewish people live in the province. The ratio of urban/rural residence was also relatively even (208,284 vs. 173,089; in 1991). During the study period, a national population census was carried out in 2011, counting a total population of 353,068 residents in Veszprem province (males: 170,504; females: 182,564) [Hungarian Central Statistical Office].

Patient inclusion lasted between January 1, 1977, and December 31, 2018. All patients in the investigated area who were diagnosed with CD in this period were included in the study. With each patient, diagnoses generated by in‐hospital or outpatient visit records were reviewed thoroughly using the Lennard‐Jones and the Copenhagen Diagnostic Criteria. The diagnosis of perianal disease was made if there was clinical, radiographic, endoscopic, or surgical evidence of a perianal fistula, or abscess. The diagnosis of perianal fistulas included simple and complex (multiple tracts), trans‐sphincteric and extrasphincteric perianal fistulas, and rectovaginal fistulas. Patient follow‐up ended on December 31, 2020.

The use of immunomodulator agents became widespread in Hungary from the mid‐1990s, while biological therapies have been commonly used and reimbursed by the National Health Insurance Fund of Hungary since 2008. Therefore, we assessed the temporal trends in therapeutic strategies and outcomes by dividing the study population into three consecutive cohorts according to the year of diagnosis: cohort A, 1977–1995; cohort B, 1996–2008 (‘immunosuppressive era’); and cohort C, 2009–2018 (‘biological era’). The only available immunomodulator agents for CD patients in the study period was azathioprine and methotrexate.

2.2 Data collection and reporting

Patients were followed up prospectively from diagnosis to the end of the follow‐up period or until the date of their emigration, lost for follow‐up or death. Patient data were collected from four general hospitals in the province and other specialised gastroenterology outpatient units. Patient data were collected and reviewed every year using public health records and questionnaires filled out by treating physicians for missing/additional data. The provincial IBD register was centralised in Csolnoky F. County Hospital, in Veszprem city. The majority of patients (over 90% of CD patients) were monitored at the Csolnoky F. County Hospital that serves as a secondary referral center for IBD patients in the province. Since 2018, a cloud‐based online interface – called National eHealth Infrastructure (EESZT) – has provided access to inpatient and outpatient medical records (including visits, endoscopy, pathology reports, imaging data, surgical procedures), drug prescription information, improving the appropriateness of the data collection in our cohort. Further detailed methodological description is also available in our previously published papers on this inception cohort.

Detailed demographic data were collected. Disease phenotype was evaluated at diagnosis and during follow‐up based on the Montreal classification. Data on medical therapy were collected from medical records of patient visits and prescription records, updated yearly. Cumulative exposure to medications was evaluated. Perianal surgical procedure was defined as any surgical procedure specific to perianal fistulae and abscesses, including the lay‐open surgery, excision of a perianal fistula, or perianal incision and excision. Time to first biological therapy initiation, first and second resective surgery, disease behaviour change, and time to first perianal surgical intervention were collected. Disease behaviour progression was defined as the development of either intestinal strictures (B2) or internal fistulas or abscesses (B3) in patients with an inflammatory phenotype (B1), according to the Montreal classification. Death and time to death were also registered and follow‐up times were adjusted accordingly.

This work was prepared in adherence to the STROBE guidelines.

2.3 Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are presented as means with standard deviation (SD), whereas categorical variables are presented as numbers with percentages. The t test or Mann–Whitney U test was used to compare continuous variables, and the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare categorical variables, as appropriate. Cumulative probabilities – with accompanying 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) – of biological therapy initiation, first perianal surgical procedure, disease behaviour progression and resective surgeries were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier analysis, and values were compared between groups by using the Log‐rank test. Multivariate regression analysis was performed to identify significant predictors of the cumulative probabilities of perianal surgery. A p < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software v. 20.0 (Chicago, IL, USA).

3 RESULTS

3.1 Study population and burden of perianal disease

A total of 946 patients (male/female: 496/450; mean age at diagnosis: 32.0 years [SD: 14.8]) were diagnosed with CD during the inclusion period in Veszprem County. Perianal disease at diagnosis was present in 17.4% (n = 165/946) of the patients in the total cohort. Median duration of follow‐up in the total cohort was 15 years (IQR: 9–21). The rate of perianal disease at the end of our follow‐up increased to 26.7% (n = 253/946), which equals to an additional 9.3% (n = 88) of patients developing perianal disease during the disease course in this cohort. For detailed patient characteristics and disease phenotype at diagnosis see Table 1.

Patients with perianal manifestation at diagnosis had significantly higher rates of penetrating disease behaviour (B3) at diagnosis (p < 0.001). Disease location at diagnosis did not show significant differences depending on the presence of perianal disease. Smoking history was also more prevalent in patients with perianal disease (p = 0.002).

Based on the time of diagnosis, n = 150 patients were classified into cohort A (1977–1995), n = 439 in cohort B (1996–2008), and n = 357 in cohort C (2009–2018). The presence of perianal manifestation at diagnosis showed a decreasing trend with 24.7% (n = 37)/18.5% (n = 81)/13.2% (n = 47) in cohorts A/B/C, respectively.

Diagnostic delay between symptom onset and definitive diagnosis of CD was significantly higher in earlier cohorts (p = 0.013). More than 2 years delay before the definitive diagnosis was observed in 20.0%/12.2%/9.5% in cohorts A/B/C, respectively.

3.2 Medical treatment

Cumulative exposure to IBD‐specific groups of medications in patients with and without perianal disease is detailed in Tables 2 and 3. Total 5‐ASA and corticosteroid exposure decreased over time, whereas the use of immunomodulators and biologicals increased in more recent cohorts. Azathioprine was the only available thiopurine immunomodulator in the study period, and the use of methotrexate was very low (1/253 in patients with perianal disease). The first‐line biological therapy among patients with perianal disease was infliximab in 68.2% (73/107), adalimumab in 30.8% (33/107) and certolizumab pegol in 0.9% (1/107) in the total study population. Second‐line biological therapy was required in 32.7% (35/107) of the patients with perianal disease. Second‐line agent was aTNF in all cases due to federal regulations. Few patients with perianal disease received vedolizumab (5/253) or ustekinumab (3/253) in the study period.

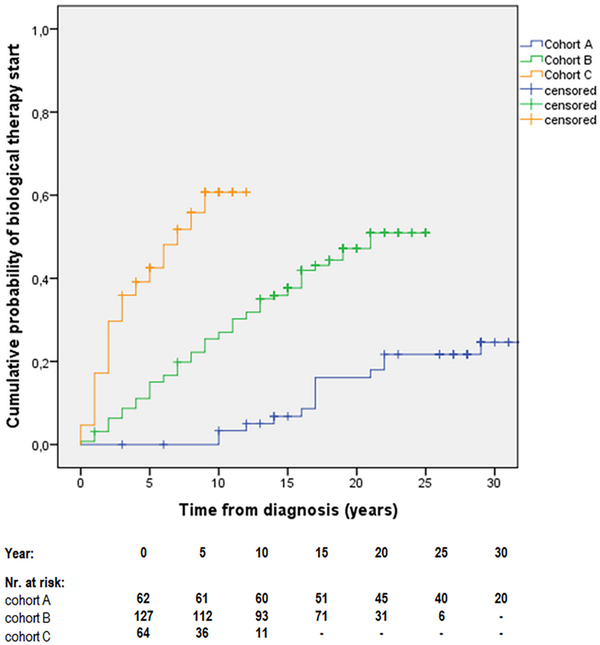

In patients with perianal disease, time‐dependent analysis showed a cumulative probability of 0.0% (95% CI: 0)/3.3% (95% CI: 1–5.6) for receiving biological therapy at 5 and 10 years after diagnosis for cohort‐A; 15.1% (95% CI: 11.9–18.3)/27.0% (95% CI: 23–31) for cohort‐B, and 42.5% (95% CI: 36.3–48.7)/60.7% (95% CI: 54.1–67.1) for cohort‐C (pLog Rank < 0.001; Figure 1).

FIGURE 1

Cumulative probability of biological therapy initiation after diagnosis in patients with perianal Crohn's disease (cohort‐A, 1977–1995; cohort‐B, 1996–2008; cohort‐C, 2009–2018) [pLogRank < 0.001; N = 253].

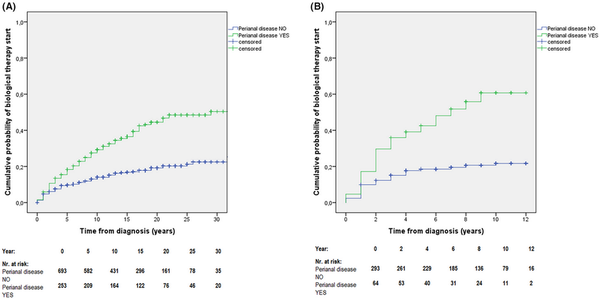

When comparing biological therapy use between patients with and without perianal disease in the total cohort, the cumulative probability of receiving biological therapy was significantly higher in patients with perianal disease during the disease course: 18.3% (95% CI: 15.9–20.7) vs. 9.7% (95% CI: 8.6–10.8) at 5 years, and 29.3% (95% CI: 26.4–32.2) vs. 14.0% (95% CI: 12.6–15.4) at 10 years (crude analysis in the total cohort, pLogRank < 0.001; N = 946; Figure 2A). A sensitivity analysis was performed for patients diagnosed in the ‘biological’ era (cohort‐C), where the 5‐ and 10‐year cumulative probability of receiving biological therapy was 42.5% (95% CI: 36.3–48.7) vs. 18.5% (95% CI: 16.2–20.8), and 60.7% (95% CI: 54.1–67.1) vs. 21.7% (95% CI: 19.1–24.1) among patients with and without perianal involvement, respectively (pLogRank < 0.001; N = 357; Figure 2B).

FIGURE 2

(A) Cumulative probability of biological therapy initiation in patients with vs without perianal disease in the total cohort (1977–2018) [pLogRank < 0.001; N = 946]. (B) Cumulative probability of biological therapy initiation in patients with vs. without perianal disease in cohort‐C (2009–2018) [pLogRank < 0.001; N = 357].

In a sub‐analysis, the cumulative probability of biological therapy initiation was stratified by both disease behaviour (stenosing or fistulizing vs inflammatory) and the presence of perianal manifestation. Results showed that patients with perianal disease had higher exposure to biologicals, regardless of disease behaviour type (Figure S1A,B).

3.3 Perianal surgical interventions

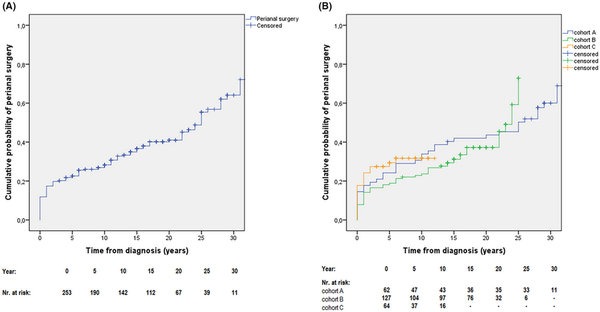

The overall rate of perianal surgical interventions in the total cohort was 44.7% (113/253). A Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed to determine cumulative probability of the first perianal surgical intervention: 22.8% (95% CI: 20.1–25.5) after 5 years, 28.3% (95% CI: 25.4–31.2) after 10 years, 41.0% (95% CI: 37.5–44.5) after 20 years, and 64.1% (95% CI: 59–69.2) after 30 years from diagnosis (Figure 3A).

FIGURE 3

(A) Cumulative probability of first perianal surgical intervention in patients with perianal disease from the total cohort (1977–2018) [N = 253]. (B) Cumulative probability of first perianal surgical intervention in patients with perianal manifestation, stratified by time of diagnosis (cohort‐A, 1977–1995; cohort‐B, 1996–2008; cohort‐C, 2009–2018) [pLogRank = 0.594; N = 253].

When we stratified patients by the time of diagnosis, the probability of first perianal surgical intervention remained similar between cohorts A/B/C: 24.2% (95% CI: 18.8–29.6)/19.9% (95% CI: 16.4–23.4)/29.4% (23.6–35.2) after 5 years, 33.9% (95% CI: 27.9–39.9)/23.6% (95% CI: 19.8–27.4)/31.7% (95% CI: 25.6–37.8) after 10 years, and 43.6% (95% CI: 37.3–49.9)/37.2% (95% CI: 32.6–41.8) in cohorts A/B after 20 years from diagnosis (pLogRank = 0.594; N = 253; Figure 3B).

A cox‐regression multivariate analysis was performed to identify predictors of first perianal surgical procedure in incident CD patients with perianal manifestation. The model identified only stenosing or penetrating (B2 or B3) disease behaviour at diagnosis (HR: 1.81; 95% CI: 1.19–2.75; p = 0.005) to be an independent predictor for first perianal surgical intervention (Table 4).

3.4 Abdominal resective surgery rates in patients with perianal disease

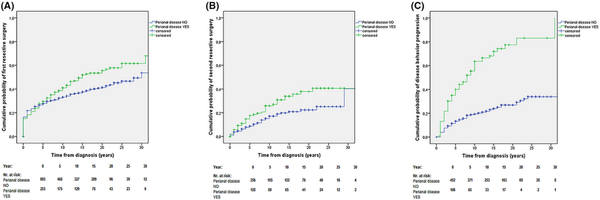

The overall rate of patients with perianal disease having any major abdominal resective surgery is 50.6% (128/253). The cumulative probability of undergoing major resective surgery was 29.5% (95% CI: 26.6–33.4) after 5 years, 41.0% (95% CI: 37.8–44.2) after 10 years, 55.6% (95% CI: 51.9–59.3) after 20 years in patients with perianal disease. The probability of undergoing resective surgery was higher in patients having perianal disease at diagnosis or developing it during their disease course compared to CD patients with no perianal involvement (pLogRank = 0.007; N = 946; Figure 4A).

FIGURE 4

(A) Cumulative probability of first resective surgical intervention in the total cohort (1977–2018) stratified by the presence of perianal disease during the disease course [pLogRank = 0.007; N = 946]. (B) Cumulative probability of second resective surgery in the total cohort (1977–2018) stratified by the presence of perianal disease during the disease course [pLogRank = 0.013; N = 384]. (C) Cumulative probability of disease behaviour progression in patients with inflammatory (B1) behaviour at diagnosis into stenosing or penetrating phenotype (B2/B3) in the total cohort (1977–2018) stratified by the presence of perianal disease during the disease course [pLogRank < 0.001; N = 558].

The overall number of patients having second resective surgery (re‐resection) was 20.3% (78/384). The probability of having second resective surgery was higher in patients with perianal disease compared to patients with no perianal involvement (pLogRank = 0.013; N = 384; Figure 4B).

In a sensitivity analysis, excluding patients who developed perianal disease later in the disease course, patients with perianal manifestation at diagnosis still had higher probability for first resective surgery compared to patients with no perianal involvement (pLogRank = 0.013; N = 858). Similar trend was observed regarding second resective surgery (pLogRank = 0.056; N = 338); however, statistical significance was not reached.

Another sub‐analysis was made on first‐ and second resective surgery rates by stratifying patients based on both disease behaviour and perianal manifestation (Figure S2A,B). Results showed that B2/B3 behaviour is a stronger driver for the probability of having resective surgery, than perianal manifestation. Among patients with B2/B3 behaviour, first resective surgery rates were higher in patients without perianal disease (pLogRank < 0.001), while second resective surgery had higher probability in patients with perianal disease (pLogRank = 0.015).

3.5 Proctectomy rates

The overall rate of proctectomy (either part of total proctocolectomy or partial colectomy) was 9.1% (23/253) among patients with perianal disease. In 3 patients, colorectal carcinoma was the indication for proctectomy (1 patient with colon carcinoma and 2 patients with rectum carcinoma). The cumulative probability of proctectomy was 2.4% (95% CI: 1.4–3.4) after 5 years, 4.2% (95% CI: 2.9–5.5) after 10 years, 10.8% (95% CI: 8.5–13.1) after 20 years, and 14.1% (95% CI: 10.8–17.4) after 30 years from diagnosis (Figure S3A). Although there was no statistically significant difference in the overall probability of proctectomy when patients were stratified by the ‘era’ of diagnosis (pLogRank = 0.579; N = 253), 10‐year proctectomy rates were numerically lower in the ‘biological era’ (cohort‐C): 6.7% (95% CI: 3.5–8.9)/5.6% (95% CI: 3.6–7.6)/1.6% (95% CI: 0.1–3.2) in cohorts A/B/C (Figure S3B).

3.6 Disease behaviour progression in patients with perianal disease

During the total follow‐up, 70.0% (71/106) of the perianal disease patients with inflammatory (B1) disease behaviour at diagnosis progressed into stenosing (B2) or penetrating (B3) phenotype. The cumulative probability of progression from B1 to B2/B3 phenotype was 40.0% (95% CI: 35.2–44.8) after 5 years, 63.5% (95% CI: 58.4–68.6) after 10 years, 77.4% (95% CI: 71.9–82.9) after 20 years in patients with perianal disease. The cumulative probability of disease behaviour progression from B1 to B2/B3 was significantly higher in patients having perianal disease at diagnosis or later in the disease course compared to the rest of CD patients (pLogRank < 0.001; N = 558; Figure 4C).

In a sensitivity analysis, excluding patients who developed perianal disease later in the disease course, patients with perianal manifestation at diagnosis still had higher rates of disease behaviour progression compared to patients not having perianal disease (pLogRank < 0.001; N = 507).

4 DISCUSSION

Studies of the prevalence and long‐term disease course of perianal CD are rare in population‐based cohorts and were largely performed in the ‘pre‐biologic’ era. In the present study, we evaluated data from a well‐established, prospective population‐based inception cohort of CD patients, extending over a period of 40 years. We observed a high rate of perianal disease among CD patients in this cohort, however, the prevalence of perianal manifestation at diagnosis decreased overt time. We observed an accelerated therapeutic strategy in patients with perianal CD. Over 40% of the patients received biological therapy after 5 years from diagnosis in the biological era (2009–2018). Patients with perianal disease had much higher exposure to immunomodulators and biologicals compared to other CD patients. Need for perianal surgical interventions was frequent and remained unchanged over the study period, although this may partly represent an active therapeutic choice rather than a complication in a proportion of patients. We confirmed that perianal disease identifies patients with a severe disease course (higher rates of resective abdominal surgeries and disease behaviour progression).

The incidence of perianal manifestation among CD patients varies widely in published literature. Lapidus et al. followed up 507 CD patients in Stockholm County, Sweden, between 1955 and 1989. Perianal fistulas occurred in overall 37% of the patients. In a population‐based cohort of 169 patients diagnosed in Olmsted County, Minnesota from 1970 to 1993, the cumulative incidence of perianal fistulizing CD was 12% after 1 year, and it doubled after 20 years from the diagnosis. In an update from the same Olmsted County cohort, 20.5% (85/414) of the CD patients diagnosed between 1970 and 2010 had at least 1 perianal or rectovaginal fistula episode during a median of 16 years follow‐up. In the present Veszprem cohort, covering mainly a similar time period (1977–2018) and having a similar median follow‐up time (15 years), we found a slightly higher but comparable cumulative rate of perianal disease (26.7%). On the other hand, the number of patients presenting with perianal disease at diagnosis was significantly higher in our cohort (17.4%) as compared to the Olmsted County data (8.2%).

The IBDSL population‐based registry, which is one of the largest available population‐based study, included 1162 CD patients, of which, 14.0% (N = 163) patients had perianal and/or rectovaginal fistula during the follow‐up (4.2% at diagnosis). The cumulative probabilities of developing a perianal and rectovaginal fistula were compared between three eras distinguished by the year of CD diagnosis. The cumulative 5‐year perianal fistula rate was 14.1% in the 1991–1998 era, 10.4% in the 1999–2005 era and 10.3% in the 2006–2011 era (p = 0.70). Another well‐established population‐based study is from Denmark, where 213 CD patients were included between 2003 and 2004. 10% (21/213) of the cohort had perianal manifestation (defined as perianal fistula or perianal abscess) at diagnosis, and 12.7% (27/213) of the patients developed perianal disease during a 10‐year follow‐up. High variation in incidence of perianal disease between CD cohorts is partly because of differences in perianal disease definitions among studies (e.g. anal ulcers and fissures, abscesses, anal skin tags are considered perianal disease by some study definitions, whilst not by others). Of note, our results show a high rate of perianal involvement at diagnosis, especially in the early cohort, which may be partly due to a delay of definitive diagnosis after symptom onset. The number of perianal patients at diagnosis decreased over time in our study with cohorts A, B and C, in parallel to the documented diagnostic delay. In cohort‐C (2009–2018), 13.2% of the patients had perianal manifestation at diagnosis which is comparable to the available pan‐European rate of 9% from the Epi‐IBD cohort in 2010.

Perianal disease was also associated with complex (B2/B3) disease behaviour in the present cohort. Penetrating disease behaviour (B3) was the most prevalent in patients with perianal disease at diagnosis, second highest in patients who developed perianal disease later during follow‐up, while it was lower in patients with no perianal involvement. Stenosing and inflammatory behaviour showed an inverse tendency in these categories, while characteristics of disease location were no different. Similar findings were shown by the population‐based cohort by Zhao et al.

Medical therapies were meticulously evaluated in this population‐based cohort. Patients with perianal disease were treated with an ‘accelerated’ treatment strategy, with earlier and more frequent use of biologicals and a higher cumulative exposure to immunomodulators. Temporal changes in medication use were also evaluated, by dividing the cohort into the three therapeutic eras. Cumulative exposure to thiopurines in patients with perianal disease was around 80% in cohorts B and C, representing the ‘immunosuppressive’ and ‘biological’ eras, respectively, and biological use was over 56% in cohort‐C. These results are comparable to findings from the recent population‐based study of Zhao et al. evaluating patients from the era of biological therapies, where 79% of the patients with perianal CD were treated with immunomodulators and 47.1% received biologicals over 10 years of follow‐up.

Similarly to the present study, the IBDSL cohort compared medical treatment and clinical outcomes of perianal patients between three eras: the cumulative 5‐year exposure to anti‐TNF agents increased from 3.1% in the 1991–1998 era, to 19.9% in the 1999–2005 era and to 41.2% in the 2006–2011 era (p < 0.01). The proportion of patients with perianal disease who received immunomodulators in our cohort was considerably higher when compared to the Olmsted County cohort in the pre‐biologic era.

We evaluated the rate of perianal surgical interventions in our cohort. A total of 113/253 (44.7%) patients underwent at least 1 perianal surgical intervention (fistulotomy, incision or excision, or abscess drainage) during our follow‐up. The cumulative risk of perianal surgery was high overall and did not change between the different ‘therapeutic eras’ in our cohort. The 5‐year probability of undergoing perianal surgery was highest in cohort‐C (29.4%). A similarly high number of patients (58.3% in total) underwent perianal minor surgery in the cohort by Zhao et al., and cumulative risk for perianal surgery was even higher in this later cohort reaching 38% after 5 years, and 67% after 10 years of follow‐up. In the IBDSL population‐based cohort, 61.5% of the patients underwent perianal surgery overall, and rates were similar in the three eras evaluated: 55.9% (1991–1998), 63.6% (1999–2005) and 58.7% (2006–2011); p = 0.71, similar to the findings in the present cohort. Of note, a significant proportion of these perianal procedures may represent an active therapeutic decision and be part of the complex medical/surgical treatment strategy and thus cannot solely interpreted as a negative outcome.

Abdominal resective surgery rates and proctectomy/total colectomy rates were high in patients with perianal disease in the present cohort, confirming that the presence of perianal disease should be interpreted as a marker of severe disease course. Need for major surgery among patients with perianal disease in our cohort was similar to that of the Danish population‐based cohort: 31% after 5 years, and 51% after 10 years from diagnosis. Proctectomy rates vary widely in published studies. In another historical cohort, the Olmstead County cohort the cumulative rate of proctectomy was 20% at 10 years after diagnosis, which is higher compared to rate in the present cohort (4.2%).

We also observed a high rate of disease phenotype progression from inflammatory behaviour to stenosing or penetrating disease in patients with perianal disease. In concordance, in a population‐based study from New Zealand including 715 CD patients diagnosed between 2003 and 2005 authors found that progression to complicated disease was more rapid in those with perianal manifestation (HR: 1.62, p < 0.001), whilst disease location remained stable.

The strength of our study includes that it is one of the largest, prospective population‐based cohort with a long‐term follow‐up of incident CD patients with perianal disease. This enabled us to evaluate time trends of long‐term medication exposures and disease outcomes over different therapeutic eras. We applied strict and consistent diagnostic criteria with reliable case ascertainment and centralised data capture with standardised data forms, which were regularly updated during follow‐up. A limitation of the study is that the disease management and medical/surgical strategy changed significantly over time, thus exposures to advanced therapies cannot be directly compared to earlier cohorts from a different therapeutic era as well as a proportion of the perianal surgical procedures may represent an active therapeutic choice especially in the latest era, thus the perianal surgery rates themselves do not necessarily represent a negative disease outcome.

In conclusion, this present population‐based study demonstrates that the burden of perianal disease was high in this cohort with more than one‐quarter of the CD patients being diagnosed with perianal disease over time. Therapeutic strategies accelerated in patients with perianal Crohn's disease over time, with high exposure to immunomodulators and biologicals. Need for perianal surgery was high and remained unchanged over time. The high rates of resective abdominal surgeries and disease behaviour progression confirm that perianal disease should be interpreted as a marker of severe CD.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lorant Gonczi: Conceptualization; formal analysis; investigation; writing – original draft. Laszlo Lakatos: Conceptualization; investigation; project administration; writing – review and editing. Petra Golovics: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Dorottya Angyal: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Fruzsina Balogh: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Akos Ilias: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Tunde Pandur: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Gyula David: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Zsuzsanna Erdelyi: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Istvan Szita: Investigation; writing – review and editing. Peter L Lakatos: Conceptualization; methodology; validation.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This work was supported by the ÚNKP‐23‐4‐II‐SE‐20 New National Excellence Program of the Ministry for Culture and Innovation from the Source of the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

LG, LL, PAG, AI, DA, FB, TP, GD, ZE, IS, AAK and LPL declare no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Declaration of personal interests: Language revision was performed by native English‐speaker.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gomollón F, Dignass A, Annese V, Tilg H, Van Assche G, Lindsay JO, et al. 3rd European evidence‐based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(1):3–25.

- 2. Burisch J, Kiudelis G, Kupcinskas L, Kievit HAL, Andersen KW, Andersen V, et al. Natural disease course of Crohn's disease during the first 5 years after diagnosis in a European population‐based inception cohort: an Epi‐IBD study. Gut. 2019;68(3):423–433.

- 3. Zhao M, Lo BZS, Vester‐Andersen MK, Vind I, Bendtsen F, Burisch J. A 10‐year follow‐up study of the natural history of perianal Crohn's disease in a Danish population‐based inception cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(7):1227–1236.

- 4. Göttgens KW, Jeuring SF, Sturkenboom R, Romberg‐Camps MJ, Oostenbrug LE, Jonkers DM, et al. Time trends in the epidemiology and outcome of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease in a population‐based cohort. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;29(5):595–601.

- 5. Zhao M, Gönczi L, Lakatos PL, Burisch J. The burden of inflammatory bowel disease in Europe in 2020. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(9):1573–1587.

- 6. Tsai L, McCurdy JD, Ma C, Jairath V, Singh S. Epidemiology and natural history of perianal Crohn's disease: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of population‐based cohorts. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2022;28(10):1477–1484.

- 7. Tarrant KM, Barclay ML, Frampton CM, Gearry RB. Perianal disease predicts changes in Crohn's disease phenotype‐results of a population‐based study of inflammatory bowel disease phenotype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103(12):3082–3093.

- 8. Gonczi L, Lakatos L, Kurti Z, Golovics PA, Pandur T, David G, et al. Incidence, prevalence, disease course, and treatment strategy of Crohn's disease patients from the veszprem cohort, Western Hungary: a population‐based inception cohort study between 2007 and 2018. J Crohns Colitis. 2023;17(2):240–248.

- 9. Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion‐Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130(3):650–656.

- 10. Sands BE, Anderson FH, Bernstein CN, Chey WY, Feagan BG, Fedorak RN, et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(9):876–885.

- 11. Lichtenstein GR, Yan S, Bala M, Blank M, Sands BE. Infliximab maintenance treatment reduces hospitalizations, surgeries, and procedures in fistulizing Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:862–869.

- 12. Lakatos L, Mester G, Erdelyi Z, Balogh M, Szipocs I, Kamaras G, et al. Striking elevation in incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease in a province of western Hungary between 1977‐2001. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(3):404–409.

- 13. Hungarian Central Statistical Office – Population Census 2011. https://www.ksh.hu/nepszamlalas/tablak_teruleti_19 Accessed 21 Apr 2022.

- 14. Lennard‐Jones JE. Classification of inflammatory bowel disease. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1989;24(suppl 170):2–6.

- 15. Munkholm P. Crohn's disease‐occurrence, course and prognosis. An epidemiologic cohort‐study. Dan Med Bull. 1997;44:287–302.

- 16. Lakatos PL, Golovics PA, David G, Pandur T, Erdelyi Z, Horvath A, et al. Has there been a change in the natural history of Crohn's disease? Surgical rates and medical management in a population‐based inception cohort from Western Hungary between 1977‐2009. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107(4):579–588.

- 17. Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, Arnott ID, Bernstein CN, Brant SR, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a Working Party of the 2005 Montreal World Congress of Gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19(Suppl A):5A–36A.

- 18. Lapidus A, Bernell O, Hellers G, Löfberg R. Clinical course of colorectal Crohn's disease: a 35‐year follow‐up study of 507 patients. Gastroenterology. 1998;114(6):1151–1160.

- 19. Schwartz DA, Loftus EV Jr, Tremaine WJ, Panaccione R, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, et al. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn's disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):875–880.

- 20. Park SH, Aniwan S, Scott Harmsen W, Tremaine WJ, Lightner AL, Faubion WA, et al. Update on the natural course of fistulizing perianal Crohn's disease in a population‐based cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(6):1054–1060.