Defined by as a construct that captures the magnitude of positive or negative associations with the self, the concept of self-esteem can be interpreted as a measure of one’s subjective thoughts of self-worth. Self-esteem has been extensively studied over the years: more than 35,000 papers exist on the topic (). There is growing evidence that self-esteem is a stable traitlike construct (; ; ); however, debate exists regarding the psychological correlates and characteristics of self-esteem development. For example, some studies have linked self-esteem to important psychological and social outcomes (e.g., ; ; ), whereas other research has questioned the importance of self-esteem (see , for a comprehensive review). As another example, many cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have found age and gender differences in self-esteem, but debate emerges regarding the precise form, timing, and origin of such differences (cf., ; ; ; ; ; ).

Two consistent findings regarding age and gender differences in self-esteem are that (a) males tend to report higher self-esteem than females during adolescence, and (b) self-esteem tends to increase from late adolescence to middle adulthood for both males and females. However, these findings are largely based on studies of Western cultures, which may not reflect self-esteem patterns in other cultures. Of the small number of studies that have examined cultural differences in self-esteem, only one study has examined age and gender differences in self-esteem in a large and globally diverse sample (see ). However, this study focuses on a limited age range (16- to 45-year-olds), only examines cultural differences across 48 (of the 196) countries in the world, and makes strict assumptions about self-esteem differences across the life span (i.e., that self-esteem changes linearly from age 16 to 45). Consequently, a complete picture of how gender and sociocultural factors interact to explain differences in self-esteem across the entire life span is lacking from the literature.

To fill this gap in the literature, the present study uses a novel application of nonparametric regression to examine gender differences in self-esteem across the life span (ages 10 to 80) using data from 45,185 participants representing 171 different countries. With this large cross-sectional sample of data collected from the World Wide Web, we address three unanswered questions about self-esteem: (a) At what ages do males and females report different levels of self-esteem?; (b) Do males and females exhibit similar self-esteem patterns across the life span?; and (c) How do sociocultural factors moderate age and gender differences in self-esteem?

Background on Self-Esteem

Age Differences

Past research suggests that self-esteem is high during childhood, a time characterized by unrealistically positive views of the self and predominately positive social feedback (). Self-esteem then declines during the transition from elementary to junior high school (; ) as children’s feelings of self-worth respond to increasingly realistic and sometimes negative feedback from peers and figures of authority (). This results in more genuine self-evaluations and, coupled with normative events such as puberty, leads to a bottoming out near the middle of adolescence (ages 14 to 15).

Self-esteem then follows a nonlinear trend throughout adulthood, increasing from the end of adolescence, peaking around ages 50 to 60, and then declining in old age (; ; ; , ; ; ). This trend matches well with theoretical perspectives of self-esteem development. Namely, adulthood is characterized by increasing stability through more complex and meaningful life relationships, greater role satisfaction, and advances in one’s career (). The combination of these facets can be argued to have a positive influence on self-esteem. Conversely, old age is marked by declines in sociocultural status, functional and chronic health problems (), and breakdowns in relationships (i.e., widowhood, retirement, etc.). It thus can be expected that self-esteem should decline in old age.

Gender Differences

A large meta-analysis conducted by reported a small but consistent gender gap across much of the life span with females reporting lower self-esteem than males. The gender gap has been replicated in a number of other studies (; ; ) but contested by some contemporary research. Similar to analysis, recent studies have replicated the relatively large gender gap in early adolescence. However, recent findings have produced mixed results regarding the gender gap in late adolescence and adulthood: found a small gender gap in young adulthood, which disappeared by old age; , ) failed to find a significant gender gap; and found a relatively small gender gap (average Cohen’s d = 0.25) from the end of adolescence to middle adulthood.

Explanations for the observed self-esteem gender gap during adolescence are varied. One explanation is that self-esteem is more strongly associated with perceptions of physical attractiveness in females (; ). As a result, unrealistically proportioned models in the media may have a negative impact on self-esteem, particularly for adolescent females (). Another theory is that gender roles are to blame (); masculinity and self-confidence—often traits associated with being a male—have been associated with higher levels of self-esteem (; ; ; ). The most likely argument is that a combination of both universal and social influences leads to the observed lower self-esteem along the female adolescent trajectory.

Sociocultural Differences

The sociocultural view of self-esteem suggests that age and gender differences can be largely attributed to social and cultural factors (; ; ). However, a vast majority of self-esteem research has been conducted on samples of subjects from the United States, making it unclear whether the well-established age and gender differences in self-esteem are specific to the United States or are indicative of something more universal. A few studies have looked at self-esteem development in countries outside of the United States, but the countries examined (Canada and Germany) fall under the umbrella of Western culture (; ), making it impossible to disassociate sociocultural and universal influences.

A noteworthy exception, recent study assessed age (16- to 45-year-olds) and gender differences in self-esteem in a large and cross-cultural (48 countries) sample of individuals. Bleidorn et al. found significant age and gender interaction effects that agree with the well-established findings: (a) males reported higher levels of self-esteem than females, and (b) self-esteem increased from late adolescence to middle adulthood. However, also found that countries displayed significant variation in the magnitudes of the age, gender, and age-gender interaction effects. Interestingly, the authors noted that (c) countries with higher gross domestic products showed larger gender gaps, and (d) the gender gap was less pronounced in East Asia and more pronounced in South and Central America.

Summary

Only a few studies have examined self-esteem differences across the life span (e.g., ; , ; ), and only one study has looked at sociocultural influences across portions of the life span (). To date, our study provides the most diverse look (in terms of life span and international representation) at age, gender, and sociocultural differences in self-esteem. Furthermore, unlike a majority of past self-esteem studies—which make rather strict (parametric) assumptions about the form of self-esteem differences across the life span—we leverage recent advances in statistical learning to explore age and gender differences in self-esteem within seven sociocultural regions: advanced economies (31 countries), East Asia and the Pacific (24 countries), Europe and Central Asia (26 countries), Latin American and the Caribbean (39 countries), Middle East and North Africa (21 countries), South Asia (8 countries), and Sub-Saharan Africa (22 countries). By taking a nonparametric and cross-validation-oriented modeling approach, we let the data determine the functional form of the gender and sociocultural differences in self-esteem across the life span. Our approach provides a robust alternative to classic methods of examining age differences in self-esteem, given that our method does not require binning the data into age ranges and/or assuming a particular (e.g., linear or quadratic) functional form for the relationship between age and self-esteem.

Method

Data Source

The data used in the present study were collected through a personality testing website that is open to the public and makes all of its data freely available online. The dataset consists of responses to the RSES () along with the age, country, and gender of the respondent. The RSES data were collected from late 2011 to early 2014, and the analyzed dataset was posted online February 15, 2014. The posted dataset contains RSES data from 47,974 subjects (61% female). We excluded 56 subjects who did not have an identifiable sociocultural region (see the Sociocultural Region Assignment section), for example, subjects using an anonymous IP address. We excluded another 1,425 subjects (<3% of subjects) who failed to complete the entire 10 items of the RSES. Finally, we excluded an additional 1,308 subjects who (a) did not meet our age range of interest (i.e., ages 10 to 80), and/or (b) identified with a gender other than male or female. In sum, we restricted our analyses to 10–80-year-old male and female subjects who completed the entire RSES and had an identifiable sociocultural region, resulting in a sample size of 45,185 subjects (62% female).

Sociocultural Region Assignment

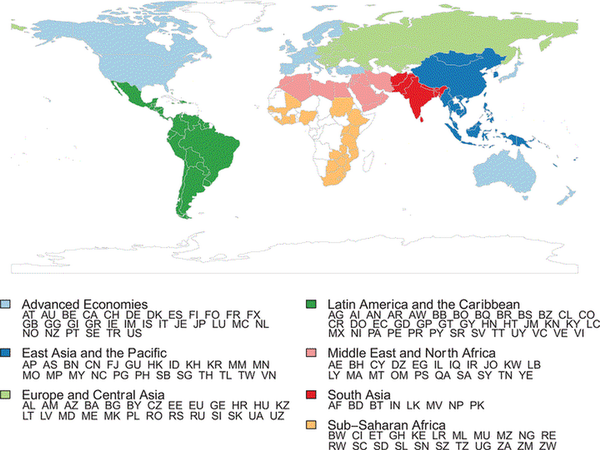

A total of 171 countries from six continents contributed to the sample. To examine how sociocultural factors influence age and gender differences in self-esteem, we leverage decades of work in the socioeconomic and education literature to study self-esteem as a function of age, gender, and sociocultural region. Specifically, we use a mapping based on the work of , ) to assign users’ country codes to one of seven sociocultural regions (Figure 1). Country codes that were unique to the current dataset were assigned to regions based on social, cultural, and economic factors similar to those used in the original mapping. Responses from users through an anonymous IP address or proxy were excluded from the analysis.

1. Mapping of the ISO country codes to the seven sociocultural regions. See the supplementary materials (countries.csv) for the country names corresponding to each ISO code listed on the map legend. Created using the R packages RColorBrewer (), maps (), and rworldmap ().

Self-Esteem Measure

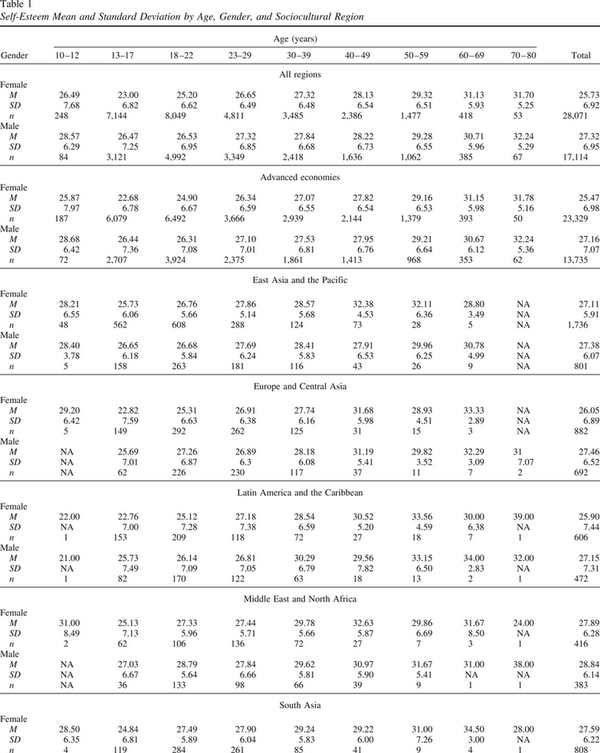

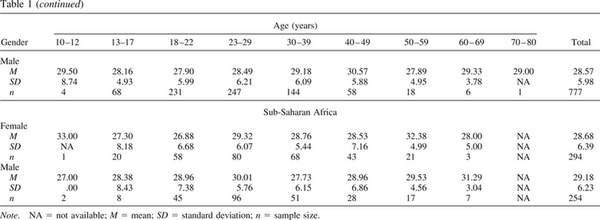

The RSES is a 10-item self-report survey and is one of the most widely used measures of self-esteem in psychological research (; ). Each item on the RSES is a statement: for example “I feel that I am a person of worth, at least on an equal plane with others.” Items are then rated on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 4 = Strongly Agree) indicating how strongly the participant identifies with the statement. We define an individual’s self-esteem as the total RSES score, that is, sum of the scores to the 10 items after recoding the negatively worded items (Nos. 3, 5, 8, 9, and 10). Table 1 and Figure 2 show the average total RSES score for each age (grouped into 9 bins), gender, and sociocultural region.

Participant Characteristics

Only 46.8% of responses were from the United States, making the sample one of the most internationally diverse self-esteem data sets currently available. The sample was reasonably diverse with respect to sociocultural region (82% advanced economies, 6% East Asia and the Pacific, 3% Europe and Central Asia, 2% Latin America and the Caribbean, 2% Middle East and North Africa, 4% South Asia, 1% Sub-Saharan Africa) and age (M = 26.7 years, SD = 12.3 years). All sociocultural regions display (a) a trend of right-skewness in the age distributions, and (b) a greater proportion of female participants. See Table 1 for a specific breakdown of the number of participants in each age group, gender, and sociocultural region.

Statistical Background

Parametric regression

Suppose that n > 1 subjects participate in an experiment that collects a response (or dependent) variable Y along with p predictor (or independent) variables X1, . . . , Xp. In this paper, the response variable is the total RSES score, and potential predictors include the age, gender, and sociocultural region of the subject. A regression model relates the response variable Y to the independent variables X1, . . . , Xp using some systematic rule. For example, the general linear model (GLM) assumes that for i = 1, . . . , n, where yi is the observed response variable for the ith subject, xi = (xi1, . . . , xip)′ is the observed predictor vector for the ith subject, β0 is the unknown regression intercept, βj is the unknown regression slope for the jth predictor, and εi ∼ N(0, σ2) are independent, identically distributed Gaussian error terms. Note that β0 is the expected value of Y when X1 = . . . = Xp = 0, and βj is the expected change in Y for a one-unit change in Xj holding the other predictors constant.

The GLM in Equation 1 is more flexible than it may appear. For example, we could define xi3 = xi1xi2, so Equation 1 includes models with or without interactions between predictors. Furthermore, note that we could define xi1 = zi and xi2 = zi2, so Equation 1 includes multiple linear regression models with or without polynomial effects. Regardless of the form of xi, the GLM assumes where xi0 = 1, that is, conditioning on the predictors in xi, the yi are assumed to be independent Gaussian variables with mean and variance σ2. Consequently, the GLM in Equation 1 is a type of parametric regression, given that the conditional mean of the response takes a known (predetermined) form, that is, , which depends on a finite number of unknown parameters, that is, β0, β1, . . . , βp.

Nonparametric regression

A nonparametric regression model is an extension of a parametric regression model that replaces the parametric mean structure with a nonparametric mean structure such as where η is an unknown function relating the response variable Y to the independent variables X1, . . . , Xp (; ; ; ; ; ). Note that a nonparametric regression model assumes that (yi|xi) ∼ N[η(xi), σ2], that is, conditioning on the predictors, the yi are assumed to be independent Gaussian variables with mean η(xi) and variance σ2. In an SSANOVA model, the goal is to estimate η from the observed data, and to decompose η such as , where ηk represents the projection of η into the kth orthogonal subspace (; ; , ; ; ). Note that the different SSANOVA subspaces correspond to different main and/or interaction effects of the predictor variables, so it is possible to form different statistical models by constraining and/or removing different SSANOVA subspaces.

Statistical Analysis

The supplemental online materials contain the R code () and data needed to replicate the analyses presented in this paper. All models were fit using the bigsplines R package ().

Age-gender model

We first perform a regression analysis that ignores sociocultural region and only takes into account the effects of age and gender on self-esteem. More specifically, we fit a two-way SSANOVA model of the form where yi is the total RSES score for the ith subject, ai and gi are the age and gender of the ith subject, η is an unknown function that describes the mean RSES trajectory across age for each gender, and εi can be interpreted as previously described. When fitting an SSANOVA model with two or more predictors, it is necessary to specify the form of the model, that is, additive versus interactive effects. In this case, there are two possible two-way SSANOVA models that we could consider: where η0 is an analog of β0 (i.e., an unknown regression intercept term), ηA is the unknown main effect function for age, ηG is the unknown main effect function for gender, and ηAG is the unknown interaction effect function.

We fit and compared the results of both the additive and interaction SSANOVA models. Note that the additive model allows each gender to have a unique offset (controlled by ηG), but requires males and females to have the same self-esteem pattern across the life span. In contrast, the interaction model allows each gender to have a unique offset (controlled by ηG) and a unique self-esteem pattern across the life span (controlled by ηAG). Clearly we expect the interaction model to fit the data better than the additive model, given that the interaction model contains an additional model term (i.e., ηAG).

To determine whether the increase in model fit is worth the added model complexity, we can use information criterion (AIC) or Bayesian information criterion (BIC): where LL denotes the maximized log-likelihood function, and df denotes the effective degrees of freedom of the model. Note that −2LL decreases as more terms are added to the model, whereas df increases as more terms are added. The model that provides the optimal balance of fit (measured by LL) and complexity (measured by df) is the model that minimizes the AIC or BIC. Note that (a) the absolute magnitudes of the AIC and BIC are not of interest, and (b) log n > 2 whenever n ≥ 8, which implies that the BIC will tend to select smaller models (i.e., those with smaller df) compared with the AIC.

The BIC performs well when the true model is finite dimensional and among the compared models (i.e., the parametric scenario), but tends to underfit the data when the true model is infinite dimensional (i.e., the nonparametric scenario). In contrast, the AIC tends to overfit the data in the parametric scenario, and perform well in the nonparametric scenario. Since the AIC is preferred in the nonparametric scenario (), we use the AIC for model selection throughout this paper.

Age-gender-region model

Next, we fit a regression model that simultaneously takes into account the effects of age, gender, and sociocultural region on self-esteem. More specifically, we fit a three-way SSANOVA model of the form where ri is the sociocultural region for the ith subject, η is an unknown function that describes the mean RSES trajectory across age for each gender and sociocultural region, and the other terms can be interpreted as previously described. In the three-way case, there are a total of nine different SSANOVA models that we could consider. The most complex model includes all possible interaction effects and has the form where η0 is an intercept term; ηA, ηG, and ηR are the main effect functions for age, gender, and region (respectively); ηAG is the age-gender interaction function; ηAR is the age-region interaction function; ηGR is the gender-region interaction function; and ηAGR is the three-way interaction function. In contrast, the most parsimonious model has the form which only includes the main (additive) effects. Seven additional models can be formed by removing various interaction effects from the most complex model. We fit and compared the results of all nine possible three-way SSANOVA models, and we used the AIC to choose the model that provides the optimal balance between fit and complexity.

Results

Age-Gender Model

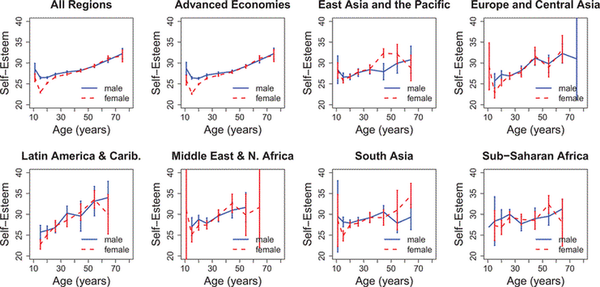

The relevant fit statistics for the additive and interaction two-way SSANOVA models are given in Table 2. The interaction model (R2 = .08) has a slightly larger coefficient of determination than the additive model (R2 = .07), which implies that the interaction effect function, ηAG, explains an additional 1% of the data variation above and beyond the main effect functions, ηA and ηG. To determine if the interaction effect function, ηAG, should be retained in the model, we can use the (previously described) AIC and BIC to select the model that provides the best fit relative to the model complexity. Both the AIC and BIC reveal that the interaction model provides the best fit relative to the model complexity, which implies that the interaction effect function, ηAG, should be retained in the model.

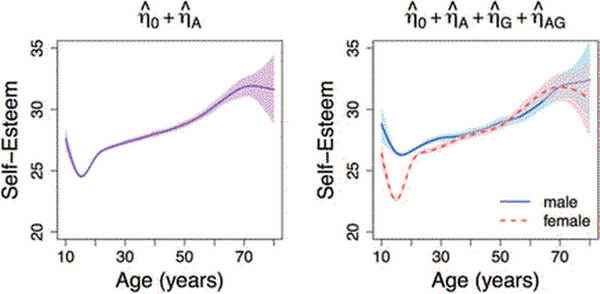

The SSANOVA predicted self-esteem trajectory across the life span is plotted in Figure 3 ignoring gender (left) and including the gender effects (right). The predictions in Figure 3 resemble the average RSES scores for the aggregate data (see Figure 2, top left). However, unlike the average RSES scores plotted in Figure 2, the SSANOVA predictions in Figure 3 provide smooth estimates of the self-esteem trajectory that can be used to make inferences about gender differences in self-esteem across the entire range of the observed data (i.e., ages 10 to 80). The shaded polygons around the self-esteem predictions in Figure 3 are 95% Bayesian confidence intervals (CIs), which have desirable across-the-function coverage properties (; ). Ages where the female and male CIs are nonoverlapping (i.e., about 10 to 30 years old) indicate a significant mean difference in reported levels of self-esteem.

3. Smoothing spline analysis of variance predicted self-esteem by age and gender. Plots depict self-esteem across the life span excluding (left) and including (right) the gender effect. The shaded polygons give 95% Bayesian confidence intervals around the predictions.

Age-Gender-Region Model

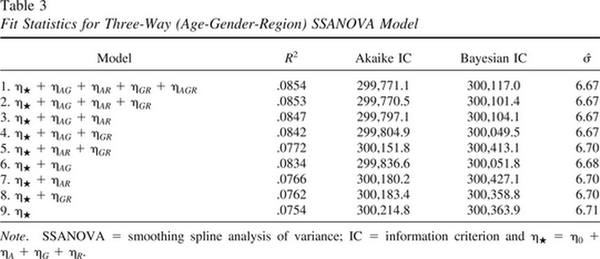

The relevant fit statistics for the nine examined three-way SSANOVA models are given in Table 3. Models 1 and 2 have the largest coefficient of determination (R2 = .085), which is not surprising, given that these models include the most effects. To determine which model provides the best fit relative to complexity, we again compare AIC and BIC values. The AIC favored the second most complex model (Model 2), which includes all two-way interaction effects. In contrast, the BIC selected Model 4, which includes two-way interactions between age-gender and gender-region. Note that the only difference between the AIC and BIC selected models is that the AIC selected model includes the age-region interaction effect, whereas the BIC selected model does not. We also note that Model 6 (which only includes an additive effect of region) produced a reasonable fit, but was not considered optimal by the AIC or BIC. The AIC is preferred in nonparametric scenarios (), so we choose the model that includes all possible two-way interactions, that is, Model 2 from Table 3.

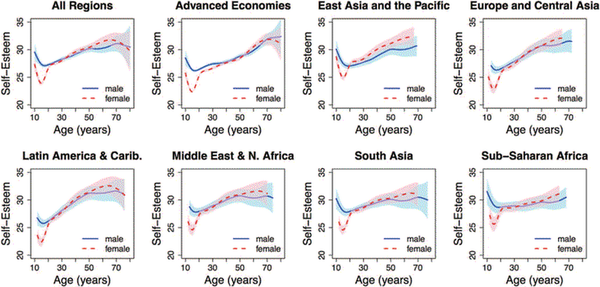

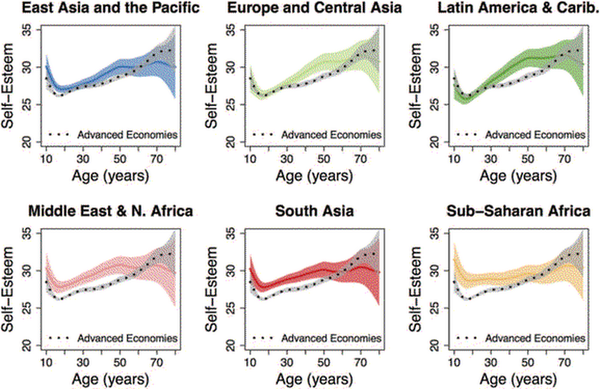

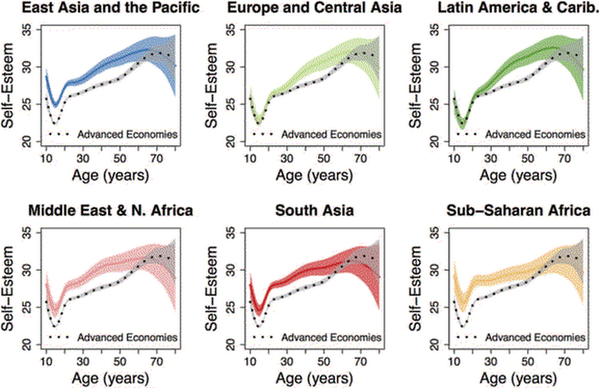

Ignoring region, the SSANOVA (Model 2) predictions in Figure 4 (top left) resemble the SSANOVA predictions in Figure 3 across the 10 to 50 age range; however, there are some noticeable differences between the solutions in the upper age ranges (50 to 70), particularly for males. Salient sociocultural similarities and differences are evident from the region-specific SSANOVA predictions in Figure 4. Self-esteem patterns observed in advanced economies match those in Figure 3, which is not surprising (82% of data are from advanced economies). One striking finding is the existence of a significant self-esteem gender gap during early adolescence within all seven sociocultural regions, although the magnitude of the gender gap is attenuated in East Asia and the Pacific (see Figure 4). Another striking finding is that males and females from advanced economies tend to report lower self-esteem than individuals from other sociocultural regions during adolescence and/or adulthood (Figures 5 and 6).

4. Smoothing spline analysis of variance predicted self-esteem by age, gender, sociocultural region. Plots depict self-esteem across the life span excluding region (top left), as well as by gender and sociocultural region (others). The shaded polygons give 95% Bayesian confidence intervals around the predictions. The region-specific predictions are restricted to the observed age range for each gender.

5. Smoothing spline analysis of variance (SSANOVA) predicted male self-esteem by age and sociocultural region. Subplots depict the SSANOVA (Model 2) predicted male self-esteem for each region (solid colored line) along with the predicted male self-esteem for advanced economies (dotted black line). The shaded polygons denote 95% Bayesian confidence intervals.

6. Smoothing spline analysis of variance (SSANOVA) predicted female self-esteem by age and sociocultural region. Subplots depict the SSANOVA (Model 2) predicted female self-esteem for each region (solid colored line) along with the predicted female self-esteem for advanced economies (dotted black line). The shaded polygons denote 95% Bayesian confidence intervals.

Discussion

Age and Gender Differences

The results of the two-way SSANOVA model reveal significant age and gender differences in self-esteem. The model predictions in Figure 3 (left) replicate previous findings regarding the life span trajectory of global self-esteem; that is, for both males and females we find that self-esteem (a) is generally inflated in childhood, (b) tends to decline during early adolescence, (c) increases from late adolescence to middle adulthood, and (d) stabilizes or declines in old age. Our results reveal that there is a significant (nonparametric) age-gender interaction effect, which implies that gender differences in self-esteem cannot be explained by a simple baseline (intercept) difference. Instead, our results suggest that males and females have significantly different self-esteem trajectories across the life span. The model predictions in Figure 3 (right) reveal that the male trajectory is approximately linear from late adolescence to adulthood, whereas the female trajectory follows a nonlinear pattern during this period.

Our findings replicate the previously noted self-esteem gender gap during early adolescence (; ; ; ), with females reporting significantly lower levels of self-esteem compared with their male counterparts (see Figure 3, right). The female self-esteem trajectory bottoms out around age 14, whereas the male trajectory bottoms out around age 17. The maximum difference between the male and female self-esteem trajectories occurs between 13 to 15 years of age, where the effect size is approximately Cohen’s d = 0.6, which is rather large according to psychological standards (). The gender gap begins to wane at approximately age 15 to 16, which is when the female trajectory takes a sharp (nonlinear) turn for the better. The gender gap is small but noticeable during the 20s with an effect size of about Cohen’s d = 0.1. From approximately age 30 to 80, no significant gender differences are observed along the self-esteem trajectory, which supports contemporary research regarding self-esteem development (, ).

Sociocultural Differences

The results of the three-way SSANOVA model in Figures 4–6 reveal unique patterns of age and gender differences in self-esteem within each sociocultural region. The AIC prefers the model containing all two-way interaction effects (i.e., Model 2), which suggests that the regional differences in self-esteem cannot be explained by a simple baseline (intercept) difference. Instead, the results imply that each sociocultural region has a unique gender-specific baseline effect and a unique age effect. Note that the AIC selected model implies that the self-esteem gender difference within each region has the same form across the life span, with a possible intercept difference. Thus, our results reveal that one’s sociocultural region has gender-specific effects on baseline self-esteem, but the effect of sociocultural region across the life span is the same for each gender.

The SSANOVA predictions in Figures 5 and 6 reveal that individuals in advanced economies tend to report as low or lower self-esteem across the life span compared with individuals in other sociocultural regions. Interestingly, we note that (a) the self-esteem pattern across the life span for males in advanced economies is most similar to that of males in East Asia and the Pacific, whereas (b) the self-esteem pattern for females in advanced economies is least similar to that of females in East Asia and the Pacific. It is also interesting to note that (c) individuals in Europe and Central Asia and in Latin America and the Caribbean have self-esteem patterns similar to individuals in advanced economies during the 10 to 30 age range, but report higher levels of self-esteem than individuals in advanced economies during the 30 to 50 age range. Furthermore, we note that (d) individuals in the Middle East and North Africa, South Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa tend to report higher self-esteem than individuals in advanced economies from adolescence to adulthood (i.e., ages 10 to 40 or 50).

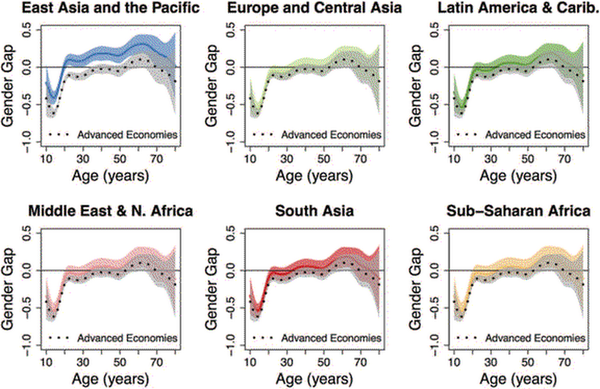

Figures 6 and 7 reveal that the adolescent dip in female self-esteem exists in all sociocultural regions, and is most pronounced from ages 13 to 15. We note that the gender gap is smaller in East Asia and the Pacific (Cohen’s d = 0.41) compared with the other sociocultural regions: d = 0.62 in advanced economies, d = 0.57 in Europe and Central Asia, d = 0.54 in Latin America and the Caribbean, d = 0.54 in Middle East and North Africa, d = 0.54 in South Asia, and d = 0.54 in Sub-Saharan Africa (see Figure 7). This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that the gender gap in East Asia is less pronounced than for other regions (). Lastly, it is interesting that we observe a gender gap reversal in East Asia and the Pacific after age 20, such that females report higher self-esteem from ages 20 to 80 (see Figure 7).

Self-esteem gender gap effect size by age and sociocultural region. Subplots depict the smoothing spline analysis of variance (Model 2) predicted gender gap effect size for each region (solid colored line) along with the predicted gender gap effect size for advanced economies (dotted black line). The gender gap effect size is defined as the mean difference in self-esteem (female minus male) divided by the estimated standard deviation , which is an analog of Cohen’s d. The shaded polygons denote 95% Bayesian confidence intervals.

Synthesis of Findings

When ignoring sociocultural region, our results in Figure 3 mostly agree with the life span trajectory of global self-esteem that is typically observed in Western cultures (; ). In particular, we find strong evidence for the two well-established findings regarding age and gender differences in self-esteem: (a) females report lower self-esteem than males during early adolescence, and (b) self-esteem increases from late adolescence to middle adulthood for both males and females. However, unlike past studies of gender differences in self-esteem across the life span, our results provide precise insight into the timing and nature of the differences. In particular, we find that females report significantly lower self-esteem than males from ages 10 to 30. The effect size of the difference is largest around age 14 (Cohen’s d = 0.6), but the difference is still salient in the 20 to 30 age range (Cohen’s d = 0.1).

Another important finding of this study is that self-esteem follows a unique and nonlinear trajectory across the life span for each gender. In particular, we find a significant nonparametric interaction between age and gender, which suggests that males and females have different self-esteem trajectories across the life span. The primary difference is that females show a larger (nonlinear) change in self-esteem during adolescence compared with their male counterparts, such that female self-esteem sharply falls (rises) during early (late) adolescence. Note that our findings challenge much past work that has modeled self-esteem across the life span using a linear (e.g., ) or quadratic (e.g., ; ) effect. Psychologically, our results imply that age differences in self-esteem do not follow the same pattern during late adolescence and adulthood. Instead, we find that self-esteem changes more abruptly during adolescence (particularly for females) and more gradually during adulthood, which is intuitive, given that adolescence is a time of rapid change.

Most importantly, our results reveal that patterns of age and gender differences in self-esteem display noteworthy similarities and differences across sociocultural regions. Two interesting findings include (a) reported self-esteem in advanced economies is lower than that in other regions during adolescence and/or adulthood for both males and females, and (b) the pattern of self-esteem across the life span shows more sociocultural variation for males compared with females. The first finding suggests that there are sociocultural aspects unique to advanced economies that negatively affect self-esteem for both males and females. With regard to the second finding, we note that self-esteem gradually rises for males in advanced economies during the 50 to 70 age range, whereas self-esteem levels off around age 50 in other regions. This could potentially be explained by an age-related shift in the experience of (common) normative events, for example, retirement. Or, perhaps just as likely, there could be an influence specific to advanced economies that yields the observed increase in male self-esteem from age 50 to 70.

One of our most striking findings is the existence of the self-esteem gender gap during adolescence within all sociocultural regions. Similar to , we find that the self-esteem gender gap is smaller in East Asia and the Pacific, but—unlike —we do not find that the self-esteem gender gap is larger in Latin America and the Caribbean (see Figure 7). The robustness of the adolescent gender gap (particularly around age 14) in all sociocultural regions suggests a universal mechanism influencing self-esteem during adolescence. This developmental period is one of change and instability (i.e., changing role structures, puberty, etc.), which could partially explain the existence of the gender gap across all sociocultural regions. However, our results confirm that sociocultural factors can moderate the self-esteem gender gap, and future research is needed to understand the unique pattern of age and gender differences in self-esteem within East Asia and the Pacific.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study has several novel benefits over other studies of self-esteem (i.e., a large and internationally diverse sample and a powerful data-driven methodology), there are a few noteworthy limitations that could be improved upon in future work. The primary limitation of this study is its cross-sectional design, which prevents us from determining which specific influences (e.g., developmental, generational, cohort effects) drive observed differences in self-esteem across the life span. In future studies, it would be useful to apply our nonparametric approach to a longitudinal study of self-esteem, which has the potential to distinguish between such effects.

Another limitation of our study is the fact that participants self-selected into the sample via the personality-testing website. As a result, our sample is restricted to individuals who were able to access the Internet, find the personality testing website, and had the time and interest to fill out the RSES (which is written in English). Thus, our participant pool may consist of individuals who have average or above-average socioeconomic status, given that all participants had access to the Internet and either (a) spoke English, or (b) were able to translate the website into their native language. In future work, it would be useful to apply our approach to a sample of participants that is guaranteed to be representative of the norms (social, cultural, economic, educational, etc.) of particular countries/regions, for example, using a data collection procedure similar to that of the World Values Survey.

Lastly, we want to mention two other sources of confound that must be considered when interpreting our results. First, we note that some research suggests that cross-cultural differences exist in response to Likert-type scales, such that individuals in individualistic cultures such as the United States tend to respond more extremely than individuals in collectivist cultures such as East Asia (). When analyzing differences in total RSES scores, this type of cross-cultural difference in response styles would manifest itself in the baseline (intercept) self-esteem score for each sociocultural region. Thus, it is unclear whether or not the reported sociocultural differences in baseline self-esteem reflect genuine intercept differences in self-esteem levels, differences in response styles, or some combination of both. Regardless, we find that a baseline (intercept) difference is not sufficient to explain the sociocultural differences in the data, which suggests that the sociocultural differences observed in this study cannot be solely attributed to cross-cultural differences in response styles.

Second, the reference-group effect is a source of potential confound when making cross-cultural comparisons, given that standards in one sociocultural region likely differ from those in another region (). When filling out the RSES, it is likely that individuals from different sociocultural regions self-report relative to different sociocultural norms and standards. This leads to a potential confound when interpreting the RSES total scores, given that observed differences in self-esteem could reflect genuine differences, differences in perceived sociocultural norms, or some combination of both. The present study does not offer any way to discern the origins of such differences, but future work could consider using a fixed sociocultural self-esteem norm to investigate the influence of the reference-group effect: for example, ask participants to compare themselves to a particular person when completing the RSES.

Concluding Remarks

Using a SSANOVA model—a framework for nonparametric regression—we examined age, gender, and sociocultural differences in self-esteem from the beginning of adolescence to old age (i.e., ages 10 to 80) using a globally diverse (53.2% international) sample of 45,185 participants from 171 different countries. To study sociocultural differences in self-esteem, we grouped the 171 countries into seven sociocultural regions (based on the work of ), and examined mean differences in self-esteem as a function of age, gender, and sociocultural region. We found that sociocultural region significantly interacts with age and gender to predict self-esteem, such that (a) females report lower self-esteem than males from ages 10 to 30 in advanced economies; (b) males and females display different self-esteem patterns across the life span in all sociocultural regions, such that female self-esteem shows more fluctuation during adolescence; and (c) sociocultural region significantly moderates patterns of age and gender differences in self-esteem. Our results reveal that some aspects of age and gender differences in self-esteem are universal across cultures (e.g., the adolescent gender gap), whereas other aspects are culture specific (e.g., baselines and patterns across the life span). Consequently, the present study helps expand the existing literature on age and gender differences in self-esteem, provides new insight into how such differences are moderated by sociocultural influences, and inspires new lines of research concerning the origins of sociocultural differences in self-esteem.

1 http://personality-testing.info/

2 Country was inferred from users’ IP address using MaxMind GeoLite.

In the SSANOVA, we use the effect size , which is an analog of Cohen’s d.

References

- Akaike H. (1974). A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Transactions on Automatic Control, 19, 716–723.

- Allgood-Merten B., Lewinsohn P. M., Hops H. (1990). Sex differences and adolescent depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 99, 55–63.

- Barro R. J., Lee J. W. (1993). International comparisons of educational attainment. Journal of Monetary Economics, 32, 363–394.

- Barro R. J., Lee J. W. (2013). A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics, 104, 184–198.

- Baumeister R. F., Campbell J. D., Krueger J. I., Vohs K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1–44.

- Becker R. A., Wilks A. R., Brownrigg R., Minka T. P., Deckmyn A. (2016). maps: Draw Geographical Maps (R package Version 3.1.1) [Computer software manual]. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=maps

- Blascovich J., Tomaka J. (1991). Measures of self-esteem. In J. Robinson, P. Shaver, L. Wrightsman (), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 115–160). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Bleidorn W., Arslan R. C., Denissen J. J. A., Rentfrow P. J., Gebauer J. E., Potter J., Gosling S. D. (2016). Age and gender differences in self-esteem—A cross-cultural window. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 111, 396–410.

- Chen C., Lee S., Stevenson H. W. (1995). Response style and cross-cultural comparisons of rating scales amongst East Asian and North American students. Psychological Science, 6, 170–175.

- Cohen J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159.

- Fenzel L. M. (2000). Prospective study of changes in global self-worth and strain during the transition to middle school. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 20, 93–116.

- Gu C. (2013). Smoothing spline ANOVA models (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

- Gu C., Wahba G. (1991). Minimizing GCV/GML scores with multiple smoothing parameters via the Newton method. SIAM Journal on Scientific and Statistical Computing, 12, 383–398.

- Hastie T., Tibshirani R. (1990). Generalized additive models. New York, NY: Chapman and Hall/CRC.

- Heine S. J., Lehman D. R., Peng K., Greenholtz J. (2002). What’s wrong with cross-cultural comparisons of subjective Likert scales?: The reference-group effect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 903–918.

- Helwig N. E. (2016). bigsplines: Smoothing splines for large samples (R package Version 1.0–9) [Computer software manual]. Retrieved from http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=bigsplines

- Helwig N. E., Ma P. (2015). Fast and stable multiple smoothing parameter selection in smoothing spline analysis of variance models with large samples. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics, 24, 715–732.

- Helwig N. E., Ma P. (2016). Smoothing spline ANOVA for super-large samples: Scalable computation via rounding parameters. Statistics and Its Interface, 9, 433–444.

- Helwig N. E., Ruprecht M. R. (2017). Self-esteem by age, gender, and sociocultural region (ICPSR36767-v1) [Data set]. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research.

- Kim Y.-J., Gu C. (2004). Smoothing spline Gaussian regression: More scalable computation via efficient approximation. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B: Methodological, 66, 337–356.

- Kling K. C., Hyde J. S., Showers C. J., Buswell B. N. (1999). Gender differences in self-esteem: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 125, 470–500.

- Kuster F., Orth U. (2013). The long-term stability of self-esteem. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, 677–690.

- Liu W., Yang Y. (2011). Parametric or nonparametric? A parametricness index for model selection. Annals of Statistics, 39, 2074–2102.

- Ma P., Huang J., Zhang N. (2015). Efficient computation of smoothing splines via adaptive basis sampling. Biometrika, 102, 631–645.

- Major B., Barr L., Zubek J., Babey S. H. (1999). Gender and self-esteem: A meta-analysis. In W. Swann, J. Langlois (), Sexism and stereotypes in modern society: The gender science of Janet Taylor Spence (pp. 223–253). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Marsh H. W. (1987). Masculinity, femininity, and androgyny: Their relations with multiple dimensions of self-concept. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 22, 91–118.

- McKinley N. M., Hyde J. S. (1996). The Objectified Consciousness Scale. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 20, 181–215.

- McMullin J. A., Cairney J. (2004). Self-esteem and the intersection of age, class, and gender. Journal of Aging Studies, 18, 75–90.

- Neuwirth E. (2014). RColorBrewer: ColorBrewer Palettes (R package version 1.1–2) [Computer software manual]. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RColorBrewer

- Nychka D. (1988). Bayesian confidence intervals for smoothing splines. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 83, 1134–1143.

- Orlofsky J. L., O’Heron C. A. (1987). Stereotypic and nonstereotypic sex role trait and behavior orientations: Implications for personal adjustment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 1034–1042.

- Orth U., Maes J., Schmitt M. (2015). Self-esteem development across the life span: A longitudinal study with a large sample from Germany. Developmental Psychology, 51, 248–259.

- Orth U., Robins R. W. (2014). The development of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 381–387.

- Orth U., Robins R. W., Roberts B. W. (2008). Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95, 695–708.

- Orth U., Robins R. W., Widaman K. F. (2012). Life-span development of self-esteem and its effects on important life outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102, 1271–1288.

- Orth U., Trzesniewski K. H., Robins R. W. (2010). Self-esteem development from young adulthood to old age: A cohort-sequential longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 98, 645–658.

- Ramsay J. O., Silverman B. W. (2005). Functional data analysis (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Springer.

- R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software manual]. Vienna, Austria. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/

- Rieger S., Göllner R., Trautwein U., Roberts B. W. (2016). Low self-esteem prospectively predicts depression in the transition to young adulthood: A replication of Orth, Robins, and Roberts (2008). Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 110, e16–e22.

- Robins R. W., Trzesniewski K. H. (2005). Self-esteem development across the lifespan. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 14, 158–162.

- Robins R. W., Trzesniewski K. H., Tracy J. L., Gosling S. D., Potter J. (2002). Global self-esteem across the life span. Psychology and Aging, 17, 423–434.

- Rosenberg M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ruppert D., Wand M. P., Carroll R. J. (2003). Semiparametric regression. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Schwarz G. E. (1978). Estimating the dimension of a model. Annals of Statistics, 6, 461–464.

- South A. (2011). rworldmap: A new R package for mapping global data. The R Journal, 3, 35–43.

- Taylor M. C., Hall J. A. (1982). Psychological androgyny: Theories, methods, and conclusions. Psychological Bulletin, 92, 347–366.

- Trzesniewski K. H., Donnellan M. B., Robins R. W. (2003). Stability of self-esteem across the life span. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 205–220.

- Trzesniewski K. H., Robins R. W., Roberts B., Caspi A. (2004). Personality and self-esteem development across the life span. In P. T. Costa, I. C. Siegler (), Recent advances in psychology and aging (pp. 163–185). Amsterdam, the Netherlands: Elsevier Science.

- Wahba G. (1983). Bayesian “confidence intervals” for the cross-validated smoothing spline. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B. Statistical Methodology, 45, 133–150.

- Wahba G. (1990). Spline models for observational data. Philadelphia, PA: Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

- Whitley B. E. Jr. (1983). Sex role orientation and self-esteem: A critical meta-analytic review. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44, 765–778.

- Wood S. N. (2006). Generalized additive models: An introduction with R. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman & Hall.