INTRODUCTION

Many sources on the Internet attribute the quote ‘It is double pleasure to deceive the deceiver’ to the Florentine philosopher and statesman Niccolò Machiavelli (1469–1527) whose writings advocated for the use of fraud and exploitation to achieve selfish goals. Ironically, there is no proof that this quote originated from Machiavelli, demonstrating how important it is to separate real information from misinformation. The misanthropic, egotistic and goal‐oriented views endorsed in Machiavelli's writings inspired psychologists to establish a personality trait that reflects agreement with these views – Machiavellianism (Mach; Christie & Geis, ). It is of pivotal interest in organizational, political and managerial areas (Belschak et al., ; Christie & Geis, ; Furnham, ) and entails the belief in the utility of manipulation, cynical views on humanity and disregard for others, guided and promoted by cheating, betrayal and search for advantages (Christie & Geis, ). A behaviour closely related to cheating and betrayal is the spread of bullshit, that is, information expressed with indifference for truth, meaning or accuracy which is supposed to impress, persuade or mislead others for individual advantages (Littrell et al., ; Littrell & Fugelsang, ). Thus, bullshit is defined by its originators' manipulative and deceptive intentions to make their recipients believe it and behave in ways the originators find desirable for their goals, regardless of whether the information is true (Frankfurt, ) or meaningful (Cohen, ). The strategic, goal‐directed behaviour to spread bullshit, called bullshitting, in turn, involves the articulation of misleading information with two related yet distinct intentions. Accordingly, individuals engaging in bullshitting aim to (a) impress (e.g., such as appearing more competent) or persuade others into doing what the ‘bullshitter’ wants them to do (e.g., by using inflated speech; persuasive bullshitting) or (b) prevent harm to oneself or others by expressing quibbling information instead of direct responses to a question (evasive bullshitting; Littrell et al., , ). For instance, a manager might tell an impressive story to provoke certain reactions from others (irrespective of whether he knows if the stories are true) or a politician avoiding a clear response to a journalist's critical question respectively.

Because particular bullshit phrases can serve both the acquisition and the defence of resources, persuasive and evasive bullshitting overlap considerably. Recent research has elaborated on the cognitive processes involved in the reception of bullshit and gained some personality‐related evidence on which individuals (do not) fall for it. For instance, those with higher cognitive abilities tend to be more critical of information and are therefore less receptive to bullshit (e.g., Čavojová et al., ). On the other hand, Littrell et al. (, ) found bullshitting to be related to dishonesty, socially undesirable responding, lower cognitive ability, lying and the tendency to overclaim one's knowledge. According to Belschak et al. (), individuals high in Mach cheat in order to prevent falling victim to others' fraud. Consistent with this, evidence supports the use of dishonesty in Mach (e.g., Muris et al., ), but it is relatively unclear yet if those high in Mach fall for misinformation. Mach reveals significant parallels with bullshitting but goes beyond it by certain long‐term motives as well as misanthropic, strategic and disagreeable orientations (Blötner & Bergold, ; Christie & Geis, ). Thus, we sought to predict individual bullshitting and the way people deal with externally provided bullshit, depending on their levels of Mach.

Areas of bullshit and closely related constructs

At the beginning of the research on bullshitting, Pennycook et al. () tested the degree to which individuals recognize pseudo‐profound statements as such and discriminate pseudo‐profound phrases from motivational philosophical quotes (which are profound by definition). Pseudo‐profound statements represent arrangements of random buzzwords. The sentences comply with syntactical rules, bear no certain meaning, but make an impression on recipients. Similarly, Evans et al. () introduced scientific bullshit. It is supposed to appear intellectual but makes no sense in terms of content or the scientific domain the statements apparently stem from (i.e., physics) as the sentences just represent strings of phony words. Gligorić et al. () added political bullshit, which aims at energizing one's voters or discrediting opponents to establish or maintain influence and resources and at preventing loss of desired goods, such as electoral votes.

Despite similarities, bullshitting is not lying (Littrell et al., ). Bullshitters and liars alike want to implement certain beliefs into another person's mind (Gligorić et al., ), but they differ concerning the way they handle the truth: While bullshitters are indifferent to the truth, liars intentionally disguise it. However, since both are supposed to mislead (e.g., Evans et al., ), they share a socially undesirable core, leading us to the assumption that bullshitting should be similarly appealing to individuals high in Mach as is lying. Given that bullshitters disseminate misleading information to attain desired goals or to prevent undesired ones (Čavojová et al., ), bullshitting unveils substantial parallels with Mach: Individuals with high scores in Mach employ various tactics to pursue social influence (Blötner & Bergold, ; Jonason & Webster, ) while disregarding potential impacts on others (Christie & Geis, ). Since individuals high in Mach aim to achieve their egotistic goals at the expense of others (‘the end justifies the means’; Jones & Paulhus, ), we expected that individuals high in Mach endorse any means they believe to be helpful to attain these goals. Given its instrumental, goal‐directed and deceptive implications, bullshitting should be one of those means.

Linking bullshitting to Machiavellianism

Recent research often treated Mach as a unidimensional trait. The reasons to do so might be twofold: On the one hand, the structure of the standard measure of Mach, the Mach IV (Christie & Geis, ) is relatively ambiguous (Blötner & Bergold, ). On the other hand, numerous studies relied on short scales blending relevant, but genuinely distinct aspects into a single score. Understanding Mach as a multidimensional trait accounts for a statistically sound factor structure, better interpretability and relations with external criteria that are more consistent with theory. For instance, Blötner and Bergold () presented a two‐dimensional, motivational concept of Mach. Machiavellian approach thereby reflects the preference towards manipulation and gaining resources. Machiavellian avoidance aims at preventing loss and taps a precarious, sceptical view of humanity. Both relate negatively to honesty and agreeableness and positively to cynicism. Thus, the facets of Mach proposed by Blötner and Bergold () refer to cheating others (Machiavellian approach) in order to not experience cheating oneself (Machiavellian avoidance; Belschak et al., ). However, due to specific cognitive, motivational and emotional backgrounds, we expected differential proclivities of approach and avoidance towards bullshitting: Given the aim to prevent any kind of potential harm in both Machiavellian avoidance and evasive bullshitting, we expected that individuals high in Machiavellian avoidance engage in evasive bullshitting more frequently than those with low scores do (H1). Both Machiavellian approach and persuasive bullshitting are supposed to foster the attainment of desired goals or goods (e.g., reputation or influence; Blötner & Bergold, ; Littrell et al., , ). Thus, we expected individuals high in Machiavellian approach to engage in persuasive bullshitting more frequently than those with low scores do (H2).

Who falls for bullshit and who does not?

Bullshit receptivity is the tendency to give inflated judgements of qualities such as meaningfulness, accuracy or veracity to ambiguous, nonsensical, meaningless or otherwise misleading information (Littrell et al., ; Pennycook et al., ). It revealed negative relations with cognitive ability and cognitive reflection, as well as positive relations with illusory pattern perception and the likelihood to endorse fake news, conspiracy theories, transcendental and other supernatural beliefs (Bainbridge et al., ; Čavojová et al., ; Pennycook et al., ; Pennycook & Rand, ; Walker et al., ). Conversely, the ability to discriminate bullshit from non‐bullshit (bullshit sensitivity; i.e., recognizing bullshit and non‐bullshit as such; Pennycook et al., ) is higher for those with higher cognitive ability. Unlike bullshit receptivity, but it is unaffected by a response bias or acquiescence (Bainbridge et al., ; Erlandsson et al., ; Evans et al., ). Hence, and given the higher ecological validity of distinguishing true from false information in daily life, we focused on bullshit sensitivity.

Distinct links between bullshitting and bullshit sensitivity

The tendency to fall or not to fall for bullshit is generalizable across contents in that individuals give judgements of meaningfulness and accuracy to bullshit content, irrespective of the domain it stems from (e.g., political, pseudo‐profound and pseudo‐scientific bullshit; Čavojová et al., ; Evans et al., ; Gligorić & Vilotijević, ). To extend the scope of the current study, we aimed to test pseudo‐scientific and pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity and to consider those as indicators of general bullshit sensitivity.

Bullshit is meant to bypass the receiver's cognitive reflection and appeals to less reflective processing of information instead (Petrocelli, ). A lack of analytical thinking (i.e., insufficiently questioning ambiguous information) is conducive to higher bullshit receptivity (Erlandsson et al., ; Pennycook et al., ). Persuasive, but not evasive bullshitting, is positively related to overclaiming and a lack of cognitive reflection (Littrell et al., , ). We argue that the more individuals care to avoid harm, the less they fall for bullshit (i.e., evasive bullshitting) because they do not exaggerate their abilities and are more aware of others' deceptive communication as they do not lack reflection. In an attempt to replicate Littrell et al.’s () corresponding finding, we expected those engaging in evasive bullshitting more frequently to be more sensitive to bullshit than those who employ less evasive bullshitting (H3). On the other hand, given that individuals engaging in persuasive bullshitting more frequently are less prone to analytical thinking and tend to overclaim their knowledge (Čavojová et al., ; Littrell et al., , ), they might be overly convinced of their abilities and do not pay abundant attention to situational cues requiring scrutiny, which, in turn, is linked to higher bullshit receptivity (Pennycook & Rand, ). Consistent with this, those utilizing persuasive bullshit or spreading fake news, conspiracy theories and supernatural beliefs more often also fall for bullshit easier than those who engage in these behaviours less frequently (Čavojová et al., , ; Littrell et al., ; Pennycook et al., ; Pennycook & Rand, ). Likewise, unlike individuals frequently engaging in evasive bullshitting, individuals frequently engaging in persuasive bullshitting cannot distinguish between statements sounding profound to them and being profound to them (Littrell et al., ). Thus, and in line with Littrell et al. (), we expected a negative link between bullshit sensitivity and the frequency of employing persuasive bullshitting (H4).

Linking Machiavellianism to bullshit sensitivity

Machiavellian avoidance

According to Pennycook and Rand (), an individual's bullshit receptivity is partly due to accepting information uncritically. Since falling for others' bullshit can cause detrimental harm or loss (Čavojová et al., ), individuals high in Machiavellian avoidance should be more aware of present information in order to prevent potential harm, driven by scepticism and distrust of others' intentions (Blötner & Bergold, ). Therefore, we hypothesized that individuals high in Machiavellian avoidance are more sensitive to bullshit than those low in Machiavellian avoidance (H5).

Machiavellian approach

According to Blötner and Bergold's () bifurcation of Mach, scepticism and distrust of others should be rather due to Machiavellian avoidance. Mach scores predominantly reflecting content referring to Machiavellian approach were unrelated to the accuracy of recognizing deceit (Wright et al., ) and both cue‐based and perceived deception detection abilities (Berger, ; Wissing & Reinhard, ). From a statistical point of view, one might expect a negative link between Machiavellian approach and bullshit sensitivity because we hypothesized a positive link between Machiavellian approach and persuasive bullshitting (H2) and a negative link between persuasive bullshitting and bullshit sensitivity (H4). However, given that extant research did not find a specific association between Mach and being cheated and that – to our knowledge – there is no study linking Mach to analytical or heuristic thinking styles, we remained agnostic concerning the link between Machiavellian approach and bullshit sensitivity and explored the path in our total model.

Current study and model summary

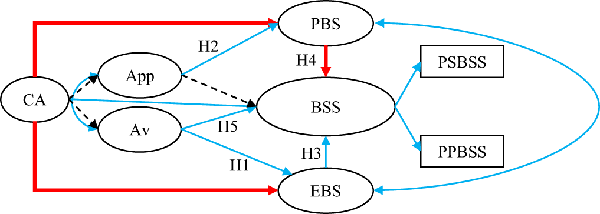

In this research, we sought to augment recent personality‐related evidence on bullshitting by examining Mach as another trait meant to explain bullshitting. Simultaneously, we addressed the question of whether Mach goes along with the likelihood of falling victim to cheating. Thereby, we distinguished two facets of Mach in order to predict differential proclivities towards production and reception of misinformation. This is a step ahead in the light of the common use of overall scores sacrificing accuracy for easy interpretations. Hence, by examining two facets, our study also contributes to a better understanding of socio‐cognitive aspects of Mach. To model shared variances among closely related constructs (especially between Machiavellian approach and avoidance, between evasive and persuasive bullshitting and between cognitive abilities and both bullshit production and sensitivity), we employed a multivariate model. Given that individuals with higher cognitive abilities are more sensitive towards bullshit (e.g., Čavojová et al., ) and engage in less bullshitting (Littrell et al., , ), we controlled for cognitive ability. Figure 1 illustrates the entire model.

FIGURE 1

Proposed relations between Mach, bullshitting and bullshit sensitivity. App and Av, Machiavellian approach and avoidance respectively; BSS, bullshit sensitivity; CA, cognitive ability; PBS and EBS, persuasive and evasive bullshitting respectively; PP, pseudo‐profound; PS, pseudo‐scientific. Red and blue lines indicate negative and positive effects respectively. Dashed lines are exploratory

METHOD

Sample

We aimed to have a sample of at least 524, based on a simulation carried out with the R package semPower [version 1.2.0; Moshagen & Erdfelder, ; see R script in the Open Science Framework (OSF) directory in Appendix S1]. The survey platform terminated the individual data collection and excluded participants if they were younger than 18 years or if they responded to know Deepak Chopra (n = 52). The authors of one of the scales we also used in our study (Bullshit Receptivity Scale [BRS]; Pennycook et al., ) derived their bullshit items from two algorithms that produce random bullshit sentences. Among others, one of these algorithms mined data from Chopra's Twitter account. Although the BRS does not represent verbatim content of Chopra, we expected biased responses from individuals who are familiar with him because these participants might have been aware of the nature of the kind of phrasing.

We recruited 922 participants from online platforms in universities and social media groups (e.g., SurveyCircle and Facebook groups for survey completion). We excluded participants if they did not pass two attention checks (‘Please click “strongly disagree”’; one presented among the items measuring scientific bullshit sensitivity and one among the items assessing bullshitting) or if they admitted that they did not participate honestly (ns = 43, 45 and 41 respectively). We did not employ imputation methods and considered only complete datasets because many participants terminated the study quite early (ns = 85, 285, 313 and 315 quit before responding to the questions concerning Chopra, the first and second attention checks and the integrity check respectively; for details on how the participants processed the study, see the next paragraphs). Ultimately, we had 525 participants [Mage = 24.41, SDage = 6.61, ranging from ages 18 to 66, 380 females (72%), 143 males (27%), 2 diverse (<1%)]. The majority were university students of psychology or related social sciences (60% held a degree equivalent to a high‐school diploma and 34% had at least a bachelor's degree).

Measures

The order in which we present the measures corresponds to the order in which the participants responded to them. For all scales not yet available in German, we used the translation–back translation approach by Brislin ().

Cognitive ability

We administered the German version of the International Cognitive Ability Resource (ICAR; Condon & Revelle, ). It measures verbal reasoning (VR), letter and number series (LN), matrix reasoning (MX) and three‐dimensional rotation (R3D) with four items each. For evidence on the validity of the ICAR, see Condon and Revelle (). In our study, the ICAR was affected by structural problems (see below). Hence, we excluded the R3D scale from the overall score, Cronbach's α = .63.

Machiavellianism

We measured Mach with the German version of the Machiavellian Approach and Avoidance Questionnaire (MaaQ; Blötner & Bergold, ). It contains four items each to assess Machiavellian approach (e.g., ‘I tend to manipulate others to get my way’; Cronbach's α = .80) and Machiavellian avoidance (e.g., ‘Anyone who completely trusts anyone else is asking for trouble’; Cronbach's α = .77; 1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree).

Bullshit sensitivity

We presented self‐translated versions of the BRS (Pennycook et al., ) and the Scientific Bullshit Receptivity Scale (SBRS; Evans et al., ) to measure pseudo‐profound and pseudo‐scientific bullshit sensitivity respectively. Participants indicated the extent to which they believe that each statement is profound (BRS) or to which it reflects a scientific fact (SBRS; 1 = disagree strongly, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = slightly agree, 5 = agree strongly). Cronbach's αs for profound phrases, pseudo‐profound phrases, scientific phrases and pseudo‐scientific phrases were .79, .86, .74 and .82 (10 items each). We computed pseudo‐profound (pseudo‐scientific) bullshit sensitivity scores by subtracting the mean profundity (scientificity) ratings for bullshit statements from the mean profundity (scientificity) ratings for actually profound (scientific) statements. Example items for pseudo‐profound bullshit, pseudo‐scientific bullshit, profound quotes and scientific facts are ‘Hidden meaning transforms unparalleled abstract beauty’, ‘Energy can deteriorate based on closed‐circuit alliterations of an afocal system’, ‘The creative adult is the child who survived’ and ‘In all energy exchanges, if no energy enters or leaves an isolated system the entropy of that system increases’.

Evasive and persuasive bullshitting frequency

We used a self‐translated version of Littrell et al.’s () Bullshitting Frequency Scale (BFS) to assess evasive (four items; e.g., ‘In my daily life, I embellish, exaggerate, or otherwise stretch the truth just a little when I want to impress the person or people I'm talking to’; Cronbach's α = .73) and persuasive bullshitting (eight items; e.g., ‘In my daily life, I embellish, exaggerate, or otherwise stretch the truth just a little when a direct answer might get me in trouble’; Cronbach's α = .87). Respondents indicated the frequency of employing each behaviour on a five‐point scale, 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally/sometimes, 4 = frequently, 5 = a lot/all the time.

Analysis plan

To ensure the structural adequacy of the scales, we computed individual confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) of all instruments using the maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors (MLR) from the R package lavaan (version 0.6–8; Rosseel, ). To test whether the proposed two‐factor structures of the constructs tested in this study were superior to the respective single‐factor solution, we compared the fit characteristics of the two‐factor and single‐factor CFAs. To examine the structure of the ICAR, we used the mean‐ and variance‐adjusted weighted least squares estimator (WLSMV) because the responses to this scale were categorical (i.e., correct or false answers). Next, we carried out bivariate correlations among all constructs. We evaluated the model proposed in Figure 1 via structural equation modelling (SEM) and the MLR estimator. To quantify the role of the control variable, we compared the patterns of parameter estimates from the proposed SEM to an SEM in which we omitted cognitive ability. To this end, we calculated the double‐entry intraclass correlation (ICCDE) between the profiles of parameter estimates, using the R package iccde (version 0.3.2; Blötner & Grosz, ). For all CFAs and SEMs, we concluded good (acceptable) model fit following the conventions provided by Hu and Bentler [; RMSEA around .06 (around .08), CFI around .95 (around .90), and SRMR < .08]. To acknowledge that our focal constructs were exclusively assessed using self‐report measures, we controlled for common method variance by adding a method factor to our SEM and comparing the factor loadings, covariances and paths of the models with and without the common method factor. This study obtained approval from the institutional review board of TU Dortmund University. The OSF directory provides the dataset, R scripts and supplemental materials (https://osf.io/q2bz5/).

RESULTS

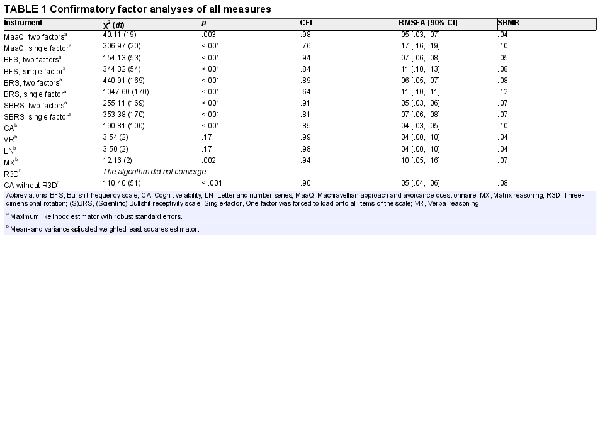

Confirmatory factor analyses

The CFAs of the MaaQ and BFS exhibited good fit concerning Hu and Bentler's () conventions and the fit characteristics of the CFAs of the BRS and the SBRS were still acceptable. All measures exhibited better fit when conceptualized two‐dimensionally (as compared to single‐factor solutions), further emphasizing the relevance of examining differential relations between facets of our constructs of interest (e.g., Machiavellian avoidance – evasive bullshitting vis‐à‐vis overall Mach – overall bullshitting; see Table 1 for a comprehensive overview). However, the correlation between the factors comprising scientific facts and scientific bullshit (SBRS) was remarkably high (r = .62; p < .001), whereas the correlation between the factors entailing profound quotes and pseudo‐profound bullshit (BRS) was much smaller, r = .32, p < .001. The empirical structure of the ICAR could not be sustained as it revealed less than acceptable fit, χ2(100) = 190.81, p < .001, CFI = .85, RMSEA = .04 [.03, .05], SRMR = .10. When we inspected the factor loadings, we found only small and/or non‐significant loadings of the items of the R3D subscale. We examined in isolation each of the four facets by computing individual CFAs of each subscale. Thereby, unlike the other subscales of the ICAR yielding acceptable to good fit and sufficiently high loadings, the CFA of the R3D subscale did not reach convergence. The fit of the ICAR was acceptable when we omitted the R3D subscale, χ2(51) = 110.40, p < .001, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .05 [.04, .06], SRMR = .08. Therefore, we based our subsequent calculations upon a restricted ICAR.

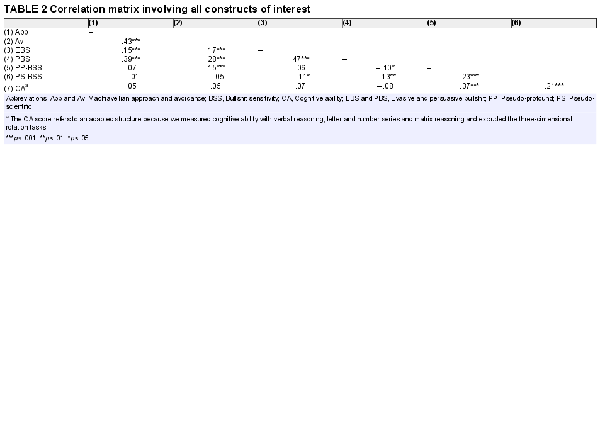

Correlations

Table 2 provides the correlation matrix involving all constructs. Both facets of Mach revealed positive correlations with evasive and persuasive bullshitting frequencies, rs ≥ .15, ps < .001. Except for a positive correlation between Machiavellian avoidance and pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity (r = .15, p < .001), the facets of Mach were statistically unrelated to pseudo‐profound and pseudo‐scientific bullshit sensitivity, rs ≤ |.07|, ps ≥ .09. Pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity revealed negative links with both persuasive and evasive bullshitting, rs ≤ −.11, ps ≤ .01. Pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity, in turn, was negatively related to persuasive bullshitting (r = −.10, p = .02), but statistically unrelated to evasive bullshitting, r = .06, p = .17. Cognitive ability did not correlate significantly with either facet of Mach or the frequencies of employing evasive and persuasive bullshitting (rs ≤ |.08|, ps ≥ .07), but correlated positively with pseudo‐profound (r = .37) and pseudo‐scientific bullshit sensitivities (r = .21, both ps < .001). Pseudo‐profound and pseudo‐scientific bullshit sensitivities yielded a positive relation, r = .23, p < .001.

Structural equation models

Given the significant yet relatively small correlation between pseudo‐profound and pseudo‐scientific bullshit sensitivities, using them as indicators of a common latent factor is not advisable. The participants' comments at the end of the survey revealed that they were hardly able to discern scientific facts from pseudo‐scientific bullshit, as can also be seen in the large latent correlation between these domains, r = .62, p < .001. Substantial modification indices suggesting cross‐loadings and residual correlations between scientific bullshit‐ and scientific fact‐related items corroborated this. Profound statements and pseudo‐profound bullshit exhibited better separability in the CFA, as the latent correlation was much smaller, r = .32, p < .001. Pseudo‐profound bullshit might be the most general area of bullshit as it is less dependent on prior knowledge regarding a specific domain (here: advanced knowledge in physics; see also Littrell et al., ; Pennycook et al., ). Hence, we focused on pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity in this article and provided the corresponding analyses with pseudo‐scientific bullshit sensitivity in the OSF supplement in Appendix S1.

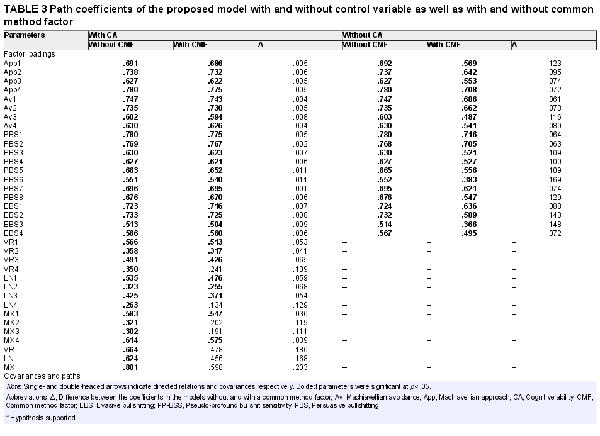

Proposed model

Unless employing pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity as our criterion, we retained the hypothesized links depicted in Figure 1. The adjusted model revealed acceptable fit, χ2(480) = 888.72, p < .001, CFI = .90, RMSEA = .04, 90% CI [.04, .05], SRMR = .05. All factor loadings were significant. Machiavellian approach, evasive and persuasive bullshitting were unrelated to pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity (−.11 ≤ βs ≤ .04, ps > .17), whereas Machiavellian avoidance (β = .14) and cognitive ability (β = .53) were linked to higher pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity (ps ≤ .04). Machiavellian approach and avoidance further exhibited positive relations with persuasive (β = .45, p < .001) and evasive bullshitting (β = .20, p < .001) respectively. Persuasive (β = −.15, p < .001) and evasive bullshitting (β = .16, p < .001) showed diametral relations with cognitive ability. However, as can be seen in Table 3, some coefficients deviated substantially from the latter illustrations (differences > .20) when we controlled for common method variance: For instance, though still insignificant, the effect sizes for the links between pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity on the one hand and evasive bullshitting, persuasive bullshitting and Machiavellian approach on the other differed substantially from the corresponding effect sizes in the model without controlling for a common method bias. Furthermore, all paths involving the control variable became insignificant.

Exclusion of the control variable

The restricted model (i.e., without the control variable) yielded satisfactory fit, χ2(182) = 444.28, p < .001, CFI = .92, RMSEA = .06 [.05, .06], SRMR = .06. Evasive (β = .22, p < .001) and persuasive bullshitting (β = −.31, p < .001) revealed opposed relations with pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity. Consistent with our original model, Machiavellian approach was statistically unrelated to pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity (β = .09, p = .16), but positively related to persuasive bullshitting (β = .42, p < .001), and Machiavellian avoidance was positively related to both pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity (β = .16, p = .01) and evasive bullshitting (β = .23, p < .001). The patterns of path coefficients and covariances of the SEMs with and without the control variable were very similar, ICCDE = .92 (see also Table 3 for an overview). Except for the link between Machiavellian avoidance and evasive bullshitting, which became insignificant when we controlled for common method variance (β = −.02, p = .89), the parameters were relatively robust against a common method bias.

We also computed the analyses using pseudo‐scientific bullshit sensitivity as a criterion (see Table S1 in the supplement). The relations between Mach and the branches of bullshitting were consistent between the models using pseudo‐scientific and pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity as criteria, but the relations between bullshit production and Machiavellian avoidance on the one hand and the respective criterion on the other differed. Furthermore, the analyses of a common method bias in the model examining pseudo‐scientific bullshit sensitivity (both with and without control variable) exhibited estimation errors, impeding the inspection of the effects of common method variance in the respective analyses.

DISCUSSION

Personality traits go along with a variety of cognitive, affective and behavioural manifestations (e.g., Lopes et al., ). This study tested whether this notion holds for the antagonistic yet non‐clinical personality trait Mach by examining whether distinct aspects of Mach are conducive to the production of and susceptibility to bullshit information. To this end, we tested the relations among two facets of Mach (Machiavellian approach and Machiavellian avoidance), two classes of bullshitting (evasive and persuasive bullshitting) and the ability to separate bullshit from non‐bullshit information (bullshit sensitivity). Consistent with the well‐established links between Mach and dishonest, egotistic attitudes and behaviours (Muris et al., ) and the loss‐preventing conceptualization of Machiavellian avoidance (Blötner & Bergold, ), we expected those high in Machiavellian avoidance to be more likely than those with low scores to use evasive bullshitting in order to prevent experiencing harm directed towards them. We suggest that the observed links between Machiavellian avoidance and evasive bullshitting were relatively small because Mach in general is an egotistic trait and evasive bullshitting involves averting harm from both self and others. The links might have been stronger if evasive bullshitting only referred to preventing harm to the self. However, in the same vein, we expected those high in Machiavellian approach to be more eager than those with low scores to produce misinformation in the attempt to gain influence (i.e., persuasive bullshitting). Based on recent considerations (Littrell et al., ), we expected negative (positive) relations between the frequency of persuasive (evasive) bullshitting and an individual's sensitivity to bullshit. Considering the dangers related to bullshit susceptibility, we hypothesized that being high in Machiavellian avoidance protects individuals from falling for bullshit because individuals high in Machiavellian avoidance are expectedly more sceptical and, therefore, more aware of deceptive intentions by others (Blötner & Bergold, ). Finally, we explored the link between Machiavellian approach and bullshit sensitivity because there was no clear theoretical or empirical indication to hypothesize a particular link between these constructs. Our results corroborated our expectations in that Machiavellian approach (avoidance) predicted higher engagement in persuasive (evasive) bullshit production and that those high in Machiavellian avoidance are more sensitive towards bullshit. When we controlled for common method variance, the facets of Mach were still related to bullshitting. The hypothesized links between bullshitting and bullshit sensitivity could only be observed when we omitted our control variable from the model and were robust against a common method bias under these circumstances.

Machiavellianism and motivationally driven production of misinformation

Littrell et al. () argued that persuasive and evasive bullshitting correspond to approach and avoidance motives respectively. Since Blötner and Bergold () have purposefully conceptualized their Mach facets in line with general approach and avoidance tendencies, overlaps with persuasive and evasive bullshitting are plausible. Although bullshitting is conceptually different from lying, our results align with studies linking Mach to the production of egotistic and conflict‐avoidance lies (McLeod & Genereux, ) and with self‐gain and white lies (Jonason et al., ) because these domains reveal meaningful parallels with persuasive and evasive bullshitting, as well as Machiavellian approach and avoidance. Likewise, studies on the facilitating effect of Mach in bargaining (Gunnthorsdottir et al., ) and poker games (Palomäki et al., ) lend empirical support to our findings because different kinds of deceptive communication behaviours are helpful to come ahead and to prevent damages (e.g., bluffing). Since the links between Mach and bullshitting frequencies remained essentially unchanged when we excluded cognitive ability from our model but differed when controlling for common method variance (Table 3), we suggest that cognitive ability did not account for these associations, but a common method bias potentially did.

Machiavellianism, supernatural beliefs and superstition

In previous studies, Mach revealed positive relations with the endorsement of conspiracy beliefs, as well as supernatural phenomena and entities, such as psychokinesis, paranormal perceptions and religiosity (Ahadzadeh et al., ; Douglas & Sutton, ; March & Springer, ; Schofield et al., ). Like many of the other stated studies, Ahadzadeh et al. () treated Mach as a non‐reflected, unidimensional trait that lacks evaluations of information as well as scepticism – an approach subject to a plethora of critique (Blötner & Bergold, ). Our differentiated view on Mach thus challenged some basic assumptions of earlier studies on similar topics. However – despite a positive association between the endorsement of conspiracy theories and susceptibility to bullshit – conspiracy theories and bullshit are conceptually distinct. Conspiracy theorists try to convince others of false claims that they believe (or at least claim) to be true, whereas bullshitters try to impress or persuade others with misleading claims and are often unconcerned whether they are true (Ahadzadeh et al., ; Pennycook et al., ).

Employing a multifaceted measure of Mach, Hart et al. () found links between particular facets of Mach and gullibility to false information. Thereby, Machiavellian tactics (Monaghan et al., ), which is similar to the Machiavellian approach facet utilized in this study (Blötner & Bergold, ), was predictive of lower sensitivity to untrustworthy cues in others, unrelated to trust in authorities, but – paradoxically – to higher trust in strangers. On the other hand, Machiavellian views (Monaghan et al., ), which is very similar to Machiavellian avoidance (Blötner & Bergold, ), was unrelated to gullibility and negatively related to trust both in authorities and strangers. Hart et al.’s () findings suggest that individuals high in Mach have difficulties in differentiating between whom they can (not) trust and, therefore, seem to contradict our findings. However, to assess gullibility, Hart et al. () asked their participants whether they believe to recognize fraudulent intentions in others, implying a response bias. Since our participants were instructed to discern profound from vacuous phrases, we had a more performance‐related assessment, which is more robust against a self‐report bias (e.g., Bainbridge et al., ).

Across seven studies, Lin et al. () found that endorsement of collectivistic cultural values (i.e., valuing societal bonds over individuality) increases the likelihood of falling for bullshit and pseudo‐scientific beliefs. Accordingly, collectivism accounts for blind trust by following the crowd without critically reflecting on information. Since collectivism represents a positive attitude towards being involved in a social group (as opposed to being a particular individual), the link between bullshit sensitivity and Machiavellian avoidance (as an attitude to believe that others have evil intentions, leading to a rejection of societal principles) is reasonable. In line with this, Schofield et al. () assumed that suspicious, distrustful aspects of Mach serve as protective factors against misinformation, and Ahadzadeh et al. () demonstrated the protective effect of scepticism against the endorsement of false beliefs. According to the latter authors, individuals with high scores in both Mach and scepticism are least likely to have false beliefs. Thus, by employing a multidimensional assessment of Mach involving distrustful, sceptical aspects as an isolated factor, we underpinned the suggestion made by Schofield et al. ().

Our findings are further in line with Ein‐Dor et al. () who claimed that it takes a liar to catch a liar. In Blötner and Bergold's () study, Machiavellian avoidance was more strongly related to honesty than was Machiavellian approach. This may have accounted for the stronger relation between Machiavellian avoidance (as compared to approach) and pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity in this study. However, persuasive and evasive bullshitting exhibited large inter‐correlations both in the current study and in those presented in the original studies (Littrell et al., , ). Therefore, multivariate models were needed to isolate shared variances among the constructs.

The role of cognitive ability in the detection of bullshit

We could not find substantial relations between cognitive ability and the facets of Mach, but cognitive abilities exhibited moderate relations with evasive and persuasive bullshitting and a large one with pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity. These findings are consistent with previous studies demonstrating that Mach and intelligence are independent (Michels, ; Michels et al., ), that intelligence has a protective effect on falling for dubious information (Andersson et al., ; Čavojová et al., ) and that those with higher cognitive abilities are less likely to employ persuasive bullshitting (Littrell et al., , ). However, unlike Littrell et al. (, ), we found a positive multivariate link between cognitive abilities and evasive bullshitting (for an exception, see Littrell et al., , Study 2). Note that Littrell et al.’s (, ) studies and the current study differed in terms of the operationalization of cognitive ability as they employed a measure mostly referring to crystallized intelligence (i.e., experience‐based), whereas we used a measure rather referring to fluid intelligence (i.e., reasoning and understanding complex rules without the use of prior knowledge). Arguably, crystallized and fluid intelligence complement each other in predicting persuasive and evasive bullshitting because different aspects of cognitive ability may amplify success in escaping uncomfortable situations (spontaneous articulation of statements helping distract the focus of a conversation; fluid intelligence) versus impressing others by appearing competent (experience‐based articulation of impressive statements; crystallized intelligence). Recent research has not investigated this in detail and the question of potentially different roles of intelligence facets was beyond the scope of our study. Thus, we can only speculate about these considerations but would like to encourage future research to examine crystallized and fluid intelligence using more extensive scales and multivariate approaches.

In our SEM, omitting the control variable did not account for major changes in the paths comprising Mach, but – given a great percentage of shared variance – the paths involving bullshitting and bullshit sensitivity were subject to substantial changes under these circumstances (see Table 3; note that the correlations in Table 2 are attenuated). According to Petrocelli (), bullshit is supposed to trigger a recipient's heuristic rather than intellectual processing of information. Given the buffering effect of cognitive ability in the reception and production of bullshit (e.g., Čavojová et al., ; Littrell et al., , ), it seems plausible that the links referring to bullshit sensitivity dissolved when we controlled for intelligence (Littrell et al., ; Pennycook et al., ). Due to the robustness of the paths involving Mach, we regard our results as support for our considerations of distinct cognitive, affective and behavioural functions of bullshitting among the facets of Mach.

Limitations

This study was not without limitations. First, our sample was very specific as it predominantly comprised female students majoring in social sciences, ultimately limiting the generalizability to more gender‐balanced populations as well as populations with more education‐related heterogeneity. For instance, men and women high in Mach differ in their use of deceptive strategies in job interviews (Hogue et al., ), moral judgements (Moore et al., ), honesty‐related behaviours (Stylianou et al., ) and deception detection (Berger, ). Relatedly, we expected that falling for or withstanding bullshit was generalizable across different content domains, such as profundity and scientificity ratings. Our findings did not corroborate this, as the correlation between pseudo‐scientific and pseudo‐profound bullshit sensitivity detected in our study was much smaller than the one observed by Evans et al. (). Čavojová et al. () suggested that falling for bullshit would be more likely if one believes to comprehend the presented information because one does not reflect on this information, whereas obscure, unknown phrases promote suspicion. Consistent with this, both bullshit and factual statements from the SBRS were likely similarly confusing to our participants because all statements referred to physics, a ‘foreign field’ for students majoring in social sciences. Pennycook et al. (), for instance, suggested that being proficient in a certain area increases the likelihood of detecting bullshit. Despite the suggested utility of this domain, we did not use political bullshit sensitivity (Gligorić et al., ) because the scale was not yet published in a peer‐reviewed journal when we conducted our study and the scale will likely be subject to revisions before finally being accepted. In our opinion, political bullshit can be a worthwhile contribution to the understanding of individual sensitivity to misinformation one faces in everyday situations. Thus, future research should examine the interplays of bullshit related to profundity, scientificity and political ratings in more detail.

Second, to our knowledge, our study was the first to examine bullshitting in a German sample, a culture characterized by an individualistic orientation and a tendency to avoid uncertainties (Hofstede et al., ). Several scholars emphasized that bullshit persuasiveness depends on cultural variables (Čavojová et al., ; Erlandsson et al., ; Lin et al., ; Littrell et al., ; Petrocelli, ). Thus, it would be desirable to replicate the current findings in collectivistic cultures as these put great emphasis on social interdependence (Lin et al., ), whereas Mach involves the desire to reject social norms in favour of egotistic goals (Christie & Geis, ). Hence, Mach stands in stark contrast to collectivistic principles.

Third, we would like to discuss the explanatory role of bullshit provided by researchers: We believe that the participants could have assumed that psychological research conveys certain intellectual goals and thus did not expect to deal with bullshit (Pennycook et al., ). In the same vein, in their review of the literature on deception and lying, Semrad et al. () concluded that extant studies have limited ecological validity because most procedures involve videos or other unnatural settings that lack emotional and non‐verbal feedback that arises in everyday deception. Unlike scientifically developed materials, everyday fraud entails certain advantages or disadvantages for liars, promoting or inhibiting deceptive behaviour and making it more or less obvious. We, as the ‘bullshitters’ in our research, did not provide the participants with salient (non‐)verbal cues indicating the verisimilitude or deceptiveness of our claims (Wissing & Reinhard, ), which might have affected our ‘trustworthiness’. Another point related to this issue concerns our reliance on self‐report assessments of deceptive behaviours and susceptibility to deception. Given that our findings were not entirely robust against a common method bias (see Table 3), more naturalistic methods other than self‐report appear necessary.

Future directions

Consistent with the presented evidence and our theoretical reasoning, Spicer () stated that bullshitting is intended to mislead and to serve one's goals and coined the labels ‘dark art of bullshit’ (p. 655) and ‘dark matter of organizational life’ (p. 657), corroborating the potentially antagonistic and socially undesired foundation. As Littrell et al. () suggested, ‘bigger bullshitters are not necessarily better bullshitters’ (p. 18). Similarly, highly Machiavellian individuals are not necessarily better liars (Michels et al., ). Nevertheless, they desire to manipulate and deceive others (Christie & Geis, ) and believe (Giammarco et al., ; Wissing & Reinhard, ) and attempt to do so, given an opportunity (Cooper & Peterson, ; Jonason et al., ). Since overall Mach is almost unrelated to cue‐based deception detectability (i.e., participants' knowledge concerning verbal, paraverbal and non‐verbal expressions occurring in deceptive behaviours, such as increased blinking; Hartwig & Bond, ; Wissing & Reinhard, ), future research might test deception detectability as a moderator in the relations between different facets of Mach and bullshit sensitivity in real‐world settings, for example in role plays or laboratory deception tasks investigating the participants' self‐generated bullshit (as opposed to scientifically administered bullshit statements generated by scholars). We suggest that verbal, paraverbal and non‐verbal cues involuntarily produced by a ‘bullshitter’ likely affect the recipient's bullshit sensitivity.

CONCLUSION

This research addressed two questions related to the roles of bullshit reception and production in Mach. First, we were interested in how ‘Machiavelli’ will most likely try to bullshit others. Based on our analyses, we conclude: It depends on how you imagine Machiavelli. If you think of a suspicious guy who does not trust humanity (‘avoiding Machiavelli’), he will most likely try to evade the situation by circumnavigating truthful statements. If you think of a manipulative guy who wants to come ahead at your expense (‘approaching Machiavelli’), he will most likely use inflated and impressive words. The second question we sought to address was whether you can bullshit Machiavelli. We suggest that the avoiding Machiavelli cannot be deceived very easily as he is distrustful and sceptical of others and, therefore, more aware of deception. However, we cannot tell whether you can bullshit the approaching Machiavelli because more information about him is required (i.e., moderator variables). These findings were mostly consistent when controlled for cognitive ability, but not necessarily when controlled for common method variance. Based on our study, we would like to encourage future research to further investigate the role of antagonistic traits in the production and reception of misinformation and thereby test the robustness of our findings, especially with more heterogeneous samples and with more heterogeneous methods going beyond exclusive self‐reports.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Christian Blötner: Conceptualization; data curation; formal analysis; investigation; methodology; project administration; resources; software; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing. Sebastian Bergold: Supervision; validation; writing – original draft; writing – review and editing.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors declare no conflict of interest.

OPEN RESEARCH BADGES

This article has earned Open Data and Open Materials badges. Data and materials are available at https://osf.io/q2bz5/.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

REFERENCES

- Bainbridge T. F., Quinlan J. A., Mar R. A., & Smillie L. D. (2019). Openness/intellect and susceptibility to pseudo‐profound bullshit: A replication and extension. European Journal of Personality, 33(1), 72–88. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.2176

- Belschak F. D., Muhammad R. S., & Den Hartog D. N. (2018). Birds of a feather can butt heads: When Machiavellian employees work with Machiavellian leaders. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(3), 613–626. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐016‐3251‐2

- Berger R. E. (1977). Machiavellianism and detecting deception in facial nonverbal communication. Journal of Psychology, 1(1), 25–31.

- Blötner C., & Bergold S. (2022). To be fooled or not to be fooled: Approach and avoidance facets of Machiavellianism. Psychological Assessment, 34(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0001069

- Brislin R. W. (1970). Back‐translation for cross‐cultural research. Journal of Cross‐Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

- Čavojová V., Brezina I., & Jurkovič M. (2020). Expanding the bullshit research out of pseudo‐transcendental domain. Current Psychology, 41, 827–836. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144‐020‐00617‐3

- Čavojová V., Secară E.‐C., Jurkovič M., & Šrol J. (2018). Reception and willingness to share pseudo‐profound bullshit and their relation to other epistemically suspect beliefs and cognitive ability in Slovakia and Romania. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 33(2), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3486

- Christie R., & Geis F. L. (1970). Studies in Machiavellianism. Academic Press.

- Cohen G. A. (2012). Complete bullshit. In M. Otsuka (Ed.), Finding oneself in the other (pp. 94–114). Princeton University Press.

- Condon D. M., & Revelle W. (2014). The international cognitive ability resource: Development and initial validation of a public‐domain measure. Intelligence, 43, 52–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intell.2014.01.004

- Cooper S., & Peterson C. (1980). Machiavellianism and spontaneous cheating in competition. Journal of Research in Personality, 14(1), 70–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0092‐6566(80)90041‐0

- Douglas K. M., & Sutton R. M. (2011). Does it take one to know one? Endorsement of conspiracy theories is influenced by personal willingness to conspire. British Journal of Social Psychology, 50(3), 544–552. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044‐8309.2010.02018.x

- Ein‐Dor T., Perry‐Paldi A., Zohar‐Cohen K., Efrati Y., & Hirschberger G. (2017). It takes an insecure liar to catch a liar: The link between attachment insecurity, deception, and detection of deception. Personality and Individual Differences, 113, 81–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.015

- Evans A., Sleegers W., & Mlakar Z. (2020). Individual differences in receptivity to scientific bullshit. Judgment and Decision Making, 15(3), 401–412.

- Frankfurt H. (2006). On truth. Knopf.

- Giammarco E. A., Atkinson B., Baughman H. M., Veselka L., & Vernon P. A. (2013). The relation between antisocial personality and the perceived ability to deceive. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(2), 246–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.09.004

- Gligorić V., & Vilotijević A. (2020). “Who said it?” How contextual information influences perceived profundity of meaningful quotes and pseudo‐profound bullshit. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(2), 535–542. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3626

- Gunnthorsdottir A., McCabe K., & Smith V. (2002). Using the Machiavellianism instrument to predict trustworthiness in a bargaining game. Journal of Economic Psychology, 23(1), 49–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0167‐4870(01)00067‐8

- Hartwig M., & Bond C. F. (2011). Why do lie‐catchers fail? A lens model meta‐analysis of human lie judgments. Psychological Bulletin, 137(4), 643–659. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023589

- Hofstede G., Hofstede G. J., & Minkov M. (2010). Cultures and organizations. Software of the mind. McGraw Hill.

- Hogue M., Levashina J., & Hang H. (2013). Will I fake it? The interplay of gender, Machiavellianism, and self‐monitoring on strategies for honesty in job interviews. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐012‐1525‐x

- Hu L., & Bentler P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Jonason P. K., Lyons M., Baughman H. M., & Vernon P. A. (2014). What a tangled web we weave: The dark triad traits and deception. Personality and Individual Differences, 70, 117–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.06.038

- Jonason P. K., & Webster G. D. (2012). A protean approach to social influence: Dark triad personalities and social influence tactics. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(4), 521–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.11.023

- Jones D. N., & Paulhus D. L. (2009). Machiavellianism. In M. R. Leary & R. H. Hoyle (Eds.), Handbook of individual differences in social behavior (pp. 93–108). Guilford Press.

- Lin Y., Zhang Y. C., & Oyserman D. (2022). Seeing meaning even when none may exist: Collectivism increases belief in empty claims. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 122(3), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000280

- Littrell S., Risko E. F., & Fugelsang J. A. (2021a). The bullshitting frequency scale: Development and psychometric properties. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(1), 248–270. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12379

- Littrell S., Risko E. F., & Fugelsang J. A. (2021b). ‘You can't bullshit a bullshitter’ (or can you?): Bullshitting frequency predicts receptivity to various types of misleading information. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(4), 1484–1505. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12447

- Lopes B., Yu H., Bortolon C., & Jaspal R. (2021). Fifty shades of darkness: A socio‐cognitive information‐processing framework applied to narcissism and psychopathy. Journal of Psychology, 155(3), 309–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2021.1880361

- McLeod B. A., & Genereux R. L. (2008). Predicting the acceptability and likelihood of lying: The interaction of personality with type of lie. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(7), 591–596. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.06.015

- Michels M. (2022). General intelligence and the dark triad: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Individual Differences, 43(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1027/1614‐0001/a000352

- Monaghan C., Bizumic B., Williams T., & Sellbom M. (2020). Two‐dimensional Machiavellianism: Conceptualization, theory, and measurement of the views and tactics dimensions. Psychological Assessment, 32(3), 277–293. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000784

- Moore K. E., Ross S. R., & Brosius E. C. (2020). The role of gender in the relations among dark triad and psychopathy, sociosexuality, and moral judgments. Personality and Individual Differences, 152, 109577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.109577

- Moshagen M., & Erdfelder E. (2016). A new strategy for testing structural equation models. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 23(1), 54–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.950896

- Muris P., Merckelbach H., Otgaar H., & Meijer E. (2017). The malevolent side of human nature: A meta‐analysis and critical review of the literature on the dark triad (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616666070

- Palomäki J., Yan J., & Laakasuo M. (2016). Machiavelli as a poker mate – A naturalistic behavioural study on strategic deception. Personality and Individual Differences, 98, 266–271. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.03.089

- Pennycook G., Cheyne J. A., Barr N., Koehler D. J., & Fugelsang J. A. (2015). On the reception and detection of pseudo‐profound bullshit. Judgment and Decision making, 10(6), 549–563.

- Pennycook G., & Rand D. G. (2020). Who falls for fake news? The roles of bullshit receptivity, overclaiming, familiarity, and analytic thinking. Journal of Personality, 88(2), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12476

- Petrocelli J. V. (2021). Bullshitting and persuasion: The persuasiveness of a disregard for the truth. British Journal of Social Psychology, 60(4), 1464–1483. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12453

- Rosseel Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

- Schofield M. B., Roberts B. L. H., Harvey C. A., Baker I. S., & Crouch G. (2022). Tales from the dark side: The dark tetrad of personality, supernatural, and scientific belief. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 62(2), 295–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221678211000621

- Semrad M., Scott‐Parker B., & Nagel M. (2019). Personality traits of a good liar: A systematic review of the literature. Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 306–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.007

- Shapiro N. R., & De La Fontaine J. (2007). The complete fables of Jean De La Fontaine. University of Illinois Press.

- Spicer A. (2013). Shooting the shit: The role of bullshit in organisations. Management, 16(5), 653–666.

- Stylianou A. C., Winter S., Niu Y., Giacalone R. A., & Campbell M. (2013). Understanding the behavioral intention to report unethical information technology practices: The role of Machiavellianism, gender, and computer expertise. Journal of Business Ethics, 117(2), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551‐012‐1521‐1

- Walker A. C., Turpin M. H., Stolz J. A., Fugelsang J. A., & Koehler D. J. (2019). Finding meaning in the clouds: Illusory pattern perception predicts receptivity to pseudo‐profound bullshit. Judgment and Decision making, 14(2), 109–119.

- Wissing B. G., & Reinhard M.‐A. (2019). The dark triad and deception perceptions. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1811. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01811

- Wright G. R. T., Berry C. J., Catmur C., & Bird G. (2015). Good liars are neither ‘dark’ nor self‐deceptive. PLoS One, 10(6), e0127315. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0127315

1 The quote cannot be derived from any particular work of Machiavelli. It seems to be a rearrangement of a quote from Jean de la Fontaine's Fables (‘What greater pleasure than to cheat the cheater!’; Shapiro & de La Fontaine, , p. 45)

2 Based on participants' comments at the end of the survey, we suggest that attrition was due to the pictographic presentation of the tasks on cognitive ability within a given time, the inability to complete those when using rather small screens (i.e., smartphone or tablet computers) and the low motivation to finish the study.

3 We would like to thank Shane Littrell for his helpful comments on potentially distinct roles of crystallized and fluid intelligence.