Introduction

The need for relational approaches to higher education has been well established in the literature (). In occupational therapy, therapeutic-use-of-self (TUS) is a long-standing foundational practice skill used by occupational therapists to actively center the client–occupational therapist relationship to improve client outcomes. Despite positioning TUS as an effective pedagogy nearly four decades ago, there remains little research that explores TUS as a relational pedagogy. An opportunity exists for occupational therapy to lead development of TUS as a relational pedagogy and fill the gap in practical, effective relational pedagogies currently experienced in higher education (). We were interested in critically exploring this further. First, we will provide a background on relational pedagogy and TUS.

Relational Pedagogy

Higher educational spaces that foster collaborative, equitable, and generative relationships among educators and students can positively shape educator and student well-being and student learning outcomes (; ; ; ). Accordingly, in higher education and health professions education, there is increasing demand for relational pedagogies (; ; ; ; ). Yet, many institutions of higher education, within which occupational therapy educational programs reside, maintain power hierarchies rooted in white, colonial, and neoliberal ideologies (; ), which fracture educator and student relationships (). Neoliberalism positions higher education as a business transaction between those with power (educators) and those without (students) (). Relational pedagogy may offer a means with which to disrupt this status quo.

Relational pedagogy can be understood as “an organic process that is responsive to the needs and desires of learners, with relationships, interactions, and community at the heart of this pedagogy” (, p. 61). While relationships can extend beyond the student–educator relationship, for example, student knowledge (), for the purposes of this study, we focused on the relationship between student and educator. Relational cultural theory is one framework that gives conceptual shape to this human-to-human focus (). First developed in psychology (), relational cultural theory has since found its way into higher education (). This theory frames human-to-human relationships as vital to growth, learning, and development (). Relational cultural theory describes how student–educator relationships can be mutually energizing and rewarding, build knowledge and personal/professional growth, and lead to a desire for more connection (). Yet, despite its known transformative potential, there are few specific, pragmatic relational pedagogies (). Thus, we believe that occupational therapy is well positioned to explore how relational occupational therapy practice skills could be adapted as relational pedagogy.

TUS: In Practice and Pedagogy

In occupational therapy, TUS is a practice skill that explicitly centers the client–therapist relationship throughout the practice process to improve client engagement and outcomes (). Drawing on psychosocial scholarship (), TUS involves the intentional and reflexive use of a therapist's personality, insights, values, and experiences, through a curious, compassionate, humble, and empathetic approach, as part of the therapeutic process (; ). To decentralize power, the use of self must reflect a true understanding of the client and their needs (). Accordingly, the occupational therapist must engage in reflexive practice to examine their own biases, prejudices, and assumptions (). presented “key elements of the self” within the therapeutic relationship including authenticity, empathy, reflexivity, responsible collaboration, and enablement (p. 87). Through TUS, the occupational therapist and client become cocollaborators in goal setting, planning, and evaluating outcomes. Through the skilled application of TUS, a therapist's most powerful tool for client occupational participation can be their self ().

proposed TUS to build constructive student–educator relationships to enhance student learning and educational outcomes (). In 2008, Haertl described the potential value of TUS in occupational therapy education, viewing it as “integral to effective teaching” (p.133). Haertl outlined the following dimensions of TUS as relevant to pedagogy: respect for the dignity and rights of everyone, empathy and compassion, humility, unconditional positive regard, honesty, a relaxed manner, flexibility, self-awareness, humor, and communication. Indeed, these dimensions of TUS align with how we previously described relational pedagogy: both TUS and relational pedagogy view relationships, co-creation, and collaboration as integral to growth and learning. This resonance sparked our curiosity in how TUS as an occupational therapy practice skill could be reconsidered and applied as a relational pedagogy. However, little continues to be known about TUS as a relational pedagogy.

Purpose and Research Questions

Centering the perspectives of our research team, we explored the experience of TUS as a relational pedagogy as situated in two Canadian entry-to-practice occupational therapy graduate programs. While the potential outcomes and implications of TUS were examined, this paper focuses on our own experiences.

To ensure methodological coherence, we began with two broad, foundational research questions followed by the communal building of sequential research questions, informed by each discussion ().

“How is TUS as a relational pedagogy experienced by students and educators in occupational therapy education?”

“How is TUS as a relational pedagogy in occupational therapy education perceived to shape student-educator relationships and learning outcomes?”

Method

Research Design

Guided by a co-constructivist paradigm, we assumed a relativist ontology, which asserts that an individual's truth is bound by their subjective experience and creates reality (; ). We chose qualitative description as the guiding methodology for our study (, ). Qualitative description gave us a subjective, inductive approach to our research with philosophical underpinnings that included an emic stance with the researcher being “active in the research process” and a focus on the description of a phenomenon (, p. 2). Furthermore, we practiced methodological borrowing to provide us with methodological grounding and flexibility () and borrowed dimensions of collaborative autoethnography methodology. We were particularly drawn to what the evocative strengths of collaborative autoethnography could offer us as we pursued our research questions.

Collaborative autoethnography is an emergent methodology where collaborative interpretation and sharing of personal experiences generate meaning within a greater sociocultural context (). In collaborative autoethnography, the researchers are the participants and the main instruments for data collection (), which is one dimension we borrowed for this study. Through examining our own personal experiences with TUS and relational pedagogy with reflexive self-study, we sought to illuminate our relationships between the sociocultural contexts of occupational therapy education and our own subjective experiences (). Collaborative autoethnography relies on an active process of self-study, reflexivity, and meaning-making resulting in rich descriptions of personal experiences (; ). This process allowed us to go further than the descriptive approach more typical of qualitative description (). In line with this study's research questions, this intimate and reflexive process lent itself well to self-discovery while also prompting examination of our respective and collective positionalities and biases. This dimension of collaborative autoethnography methodology offers a relational focus that aims to bridge the divide between researcher and participant, and student and educator, building on the premise that our identities are intertwined. This relational focus appealed to us as we sought to mitigate inherent hierarchical power dynamics in our research team. Striving toward nonhierarchical relationships supported our mutual story, through sharing and engagement, both of which resonate with the aims of TUS. We also valued that collaborative autoethnography is exploratory—there are no hard and fast rules; this dimension of collaborative autoethnography informed our flexible attitude toward the outcome of the study (). Pragmatic considerations that shaped our methodology included our 1-year timeline, striving toward anonymity for those of us who were student researchers about to embark on our transition to practice at the time of the study, and the diffusion of our research team once the study was completed, as we, student researchers, left our respective programs and began work as occupational therapists and we, educator researchers, remained at our respective institutions.

Ethical Implications

We positioned ourselves, the researchers, as participants. As a result, at the time of this study, there were inherent social risks regarding loss of privacy and/or reputation due to limitations in anonymity within our small participant group and the inherent power over stance of the educator–participants over the student–participants. Borrowing from autoethnography, we had to relationally consider “the ethical boundaries between the self and the other [to anticipate] ethical dilemmas” (, p. 1605). Thus, we worked to preserve the integrity of the study while taking caution not to disrupt our lives as we became part of the story (). We named and discussed the inherent risks, especially for student–participants, as we wanted to speak openly and mitigate fallout that may have consequences on student–participants’ education and practice. For educator–participants, we named our privilege and relative safety from the fallout, as we have relative job security and social capital in our respective institutions. As a research team, we engaged in a thorough and collaborative process to generate the consent form and discussion guide. Educator–participants strived to “step back” during these dialogues to create space for student–participants. We did this to center student–participant voices and needs. We each provided informed consent. We also decided that any one of us could veto publication of specific data points and/or personal quotations. We also removed information that might identify nonparticipants and chose pseudonyms for ourselves. This is a dimension we did not borrow from collaborative autoethnography, which seeks to unabashedly and intentionally center the person and their story. We chose a word to use to indicate off-camera discussions and we were able to withdraw from the study at any time.

Ethics approval was received from the University of Toronto's (UofT) Health Sciences Research Ethics Board (#42029) and the University of British Columbia's (UBC) Behavioural Research Ethics Board (#H22-00231). A data transfer agreement was signed by each institution to support secure data transferring cross-institutionally.

Participants

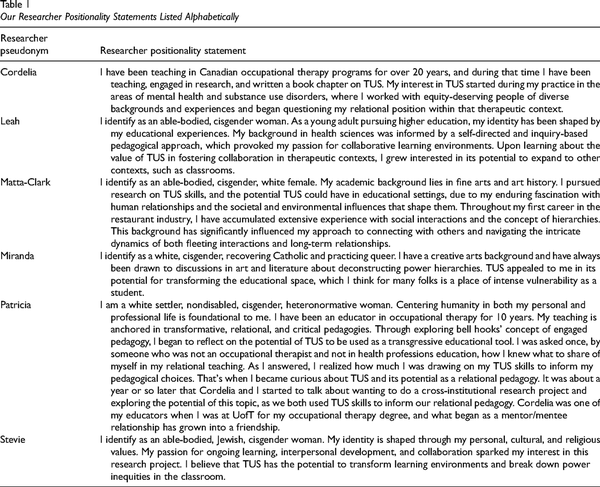

As previously discussed, we were the participants in our study. We are two professional entry-level occupational therapy students and one teaching faculty member from each of UofT and UBC. Please see Table 1 for our researcher positionality statements. Both of us educators have competency with using TUS as occupational therapists and are involved in the teaching of TUS in our respective occupational therapy programs. We, students at the time of this study, learned and applied TUS throughout our occupational therapy education and use it now in our practice as occupational therapists.

Procedures

We chose repeated discussion sessions to promote trust and relationship-building between us and to allow us to become closer to the studied phenomenon (). We used free-flowing discussion groups for data collection to generate rich, authentic data via “research as conversation” (, p. 288). As researchers participating within discussion groups, we each played a facilitator role, which worked to decentralize power in the study ().

Data collection procedures were borrowed from collaborative autoethnographic study, wherein researcher–participants participate in all aspects of the research through a collaborative, iterative, and reflexive process. To account for the geographical distance between research teams and COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in place at the time of the study, both in Vancouver and in Toronto, we conducted our discussions using secure institutional Zoom accounts from private, participant-chosen locations. Five discussion sessions took place over 4 months and were divided into two phases of inquiry. The first two sessions collected information concerning participants’ subjective experience of student–educator relationships and TUS within their respective programs. The following two sessions delved deeper into personal narratives, explored nuance, and resulted in a more comprehensive understanding of TUS. We reserved the final session for discussing the implications of TUS in entry-level occupational therapy education, challenges and limitations, outcomes, and ethical considerations. The exact content of topics, questions, and prompts for each discussion were developed collaboratively. All study materials were stored on the UofT OneDrive, only accessible to the research team.

Data Analysis

We practiced data analysis as an ongoing, active, and collaborative process (). We used ) six phases of reflexive thematic analysis approach. For Phase 1, familiarization with the data, audio data were transcribed using Zoom's internal transcription software, and we, as a team, respectively reviewed the transcripts for accuracy and to engage with content. While all proper nouns were replaced with pseudonyms, as a research team we understood that it would be possible to identify us, given our small number and the methodology. Each transcript was transferred to a collaborative excel spreadsheet in the OneDrive folder. Each of us read the transcripts in full once for reflexive memoing. As described by , memo writing is a valuable tool when reviewing data to organize data; capture timely, initial responses; capture context; and contribute to the coding process (Chang et al., 2013; ). Each of us also memoed during discussions. After each discussion, each of us recorded additional memos and reflections along the margins of the transcript. These additions created questions for further inquiry during subsequent sessions, which were recorded in the next session's guide.

For Phase 2, generating initial codes, full transcripts were reviewed additional times for iterative and collaborative coding, which involved further familiarization with the data. We used meetings to facilitate discussion of coding and collective decision-making around grouping data through iterative engagement; from here we described draft themes (Phase 3). This process was iterative and ongoing throughout the discussions (Phase 4) and done until we decided that the themes meaningfully expanded on the study aim (Phase 5) (Chang et al., 2013). To support theme generation, we used an online collaborative tool to visually capture relationships among codes, creating thematic maps (). We selected illustrative quotes and vignettes from the transcripts to support rich descriptions of each theme (Phase 6). We did not use all data.

Findings

Our analysis described four themes that centered on the transactional nature of higher education, how TUS is used and experienced in occupational therapy education, and how TUS can challenge status quo power hierarchies.

Education as Transaction

We engaged in an exploration of the contextual realities of higher education to better understand the impacts of TUS as pedagogy. We discussed how in Canada higher education institutions are shaped by neoliberalism and education has become a consumer product. “Education as transaction” explores the student–educator dynamic we experienced when occupational therapy students pay for their education. With a professional entry-level occupational therapy degree seen as a purchased product, we students experienced expectations around educator performance and the quality of the education provided. For us educators, “education as a transaction” was experienced as a capitalist focus on learning resulting in packed curricula, high workloads, and large class sizes—all of which undermine our capacity as educators to build authentic relationships with students. Stevie shared that achieving high grades was a transactional way to “forge a relationship with professors or to stand out” because of “the limited opportunities that we have to connect, especially one-on-one with our professors.”

Grading systems gave us educators the power to grant or deny a student their degrees, positioning us as guardians of the profession. Miranda reflected that “grades seem to be the thing that transforms professors into gatekeepers of education that students pay for. We pay for a credential … and so there's always going to be a power differential.” All of us felt that grading and evaluations of student learning limited collaborative learning. These evaluations reinforced status quo power imbalances prevalent in occupational therapy education. Patricia, shared:We all experienced how grades foster competition among students to obtain the best marks, the best jobs, and the best futures. Leah explained “if I can't get the scholarships, if I can't get the grant, if I can't get a good job coming out of the program, then that's going to affect my ability to get a house.”

The systems are in place … higher ed—and really since kindergarten. We've been conditioned to care about grades and look to the teacher to tell us who we are and how good we are—but … they're really in direct conflict with relational pedagogy….

Toward Authenticity in Learning

We also described how traditional pedagogies in higher education give educators power over students and position the educator as infallible and inauthentic. Patricia acknowledged that holding such power as an educator feels performative and limits her ability to show up authentically in her teaching:Matta-Clark pointed to entrenched oppression within higher education starting with the words educators use including binary values of “good” and “bad” and “pass” or “fail”:

I have power in this space and [I have to] know all the answers and I have all the information and, you know, so it's this like hoarding [of power] and power out of fear, of oh my gosh, what if people realize I'm not as powerful as I think I'm supposed to be?”

There's that dominant language or power language to hold us in place, so having these moral and oppressive words or understanding that don’t necessarily promote growth or … learning.

For us, TUS is a pedagogy that can shift away from traditional power imbalances and toward collaborative learning relationships. Cordelia shared “…our learning is not an additive thing. It's an interactive thing and we can learn so much more together … through our sharing of ideas and resources.” Practicing TUS prompts educators to reveal themselves as real people who are not all-knowing; they have anxieties, emotions, and personalities outside of the classroom: “[TUS] brings humanity to learning spaces [it] humanizes students and educators” (Patricia). Realness and authenticity were described over 25 times in the transcripts as a means to level power hierarchies in occupational therapy education. Cordelia noted that being a truly authentic educator who uses TUS effectively requires effort and skill that not every educator has the capacity or bandwidth to do, particularly within neoliberal higher education:

A lot of teachers have a difficult time building these collaborative learning classrooms, it's just they don't feel like they have the skills … [and] the cognitive load is huge.

Sharing power within education may then involve a mutually reciprocal effort on behalf of student and educator. Stevie shared:

I think initially the educators do hold most of the cards but moving forward in order for TUS to be successful, it does require the students to also play a role… I don't think it's a one-way thing. It definitely requires both students and educators to be actively involved.

Reciprocity and accountability are required by both educators and students to build mutually generative and authentic educational experiences.

Experiencing TUS: “It Makes Me Care More”

Supported by mutual kindness, empathy, caring, and support, we educators experienced TUS as a liberating practice, and we students reported a sense of being seen, valued, and validated. Cordelia noted that as an educator, the experience and practice of TUS involved “allowing yourself to be vulnerable and allowing yourself to think differently.” We students described feeling a sense of “grounding” when TUS was used as pedagogy. We all experienced TUS as relational pedagogy that enhances “collaborative and reciprocal learning” (Stevie). Knowing she held power and could make an impact on her own learning, Matta-Clark reported that she became more invested in her learning: “it makes me care more.”

For us educators, TUS helped provide “a space for open conversation, listening, and opportunities for sharing” (Cordelia) through a tangible and accessible framework for teaching relationally. Furthermore, as TUS is an occupational therapy skill, we educators had long practiced it, and so it was easier and felt familiar for us to integrate into our teaching. The embodied, reflexive work of TUS helped us to support actions that were in the service of students’ education. Patricia referred to the “critical reflexivity piece” built into TUS questioning:Like other aspects of TUS, we discussed how critical reflection and reflexivity is a skill and can vary in how effectively it is practiced from one educator to the next:

Why am I doing this? Is this about me and my ego and my needs or is this about enhancing relationship?… It's that anchoring yourself and having clarity around your values and also having people who will call you on your shit.

You’re critically reflective at your own level, and it's actually quite a deep level for you but there's always going to be some people who are far more critically reflective, are far more comfortable sharing their failures or being vulnerable. (Cordelia)

So, we experienced that although TUS as a relational pedagogy can produce positive learning experiences for both students and educators, capacity, effort, skill, and vulnerability need to be reflexively managed. We understood that across occupational therapy educational programs, the experience of TUS by students and educators will differ depending on who is involved and the context. Leah noted that there is no “one perfect, harmonized picture” of TUS—no manual or set of instructions, which creates space for diversity:

With therapeutic-use-of-self, we’re bringing in our own perspectives and backgrounds, all of which is [sic] different … so [TUS] would be so diverse to account for the diversity of all of the people who were putting it in action.

Relationship as Resistance: How TUS Transforms Power in Education

When TUS is used skillfully, we experienced that the centering of relationships could push back against oppressive systems that restrict relational education. We educators felt TUS could create more generative learning spaces where students and educators could feel secure enough to challenge each other in a compassionate way. Patricia questioned:Patricia reflected that employing TUS does require effort for educators but also holds great capacity for transformative change: “[TUS] is work, and this project is an opportunity to push back [against] the oversimplification and the dismissal of [the] relationship as a source of power.”

How much more [can we] get out of education? And how much further could our profession go? [When] you're equally engaging the minds and experiences of everybody in that space, not just sort of towing the line with what the dominant discourse is.

We also imagined what would be possible if TUS was normalized, used consistently, and supported at all levels of occupational therapy education. In that “hypothetical universe,” Miranda asserted that there would not just be “authentic meaningful relationships between student and teacher, but you would also see authentic relationships between student and student” resulting in “more collaborative, lateral learning.” By TUS addressing the hierarchical power that exists in occupational therapy education, we believe TUS could mitigate student-to-student competition where students may not be trying to undercut each other for the educator's gaze, the best grades, the best positions, and the best jobs. We also imagined the impact TUS could have beyond the classroom walls, a transformative force rippling out. Matta-Clark described it as follows:

I feel a lot more confident in asking for my needs to be met … trying to carve out what it is that I actually need in a lot of my relationships, not just my school relationships … to make me thrive as opposed to scrambling … it's not just reserved for the school setting anymore.

Discussion

Through our study, we developed initial understandings of the experiences of occupational therapy students and educators regarding the use of TUS as a relational pedagogy. Furthermore, we believe our findings offer nuanced and contextualized insights into the dynamic and complex nature of navigating relationships and power among students and educators across two large, urban Canadian graduate entry-to-practice occupational therapy programs.

Over decades, Canadian post-secondary institutions have been defunded and enrollment and tuition increased to yield higher revenue streams (). Working conditions have been adversely affected as funds have not been redirected into additional resources for teaching and learning (). The commodification of higher education, within which occupational therapy education resides, has contributed to larger class sizes, fewer opportunities to connect, and pedagogical approaches that can be scaled up; the outcome is an increased distance between students and educators (; ). Our study aligns with existing literature that affirms how the transactional nature of higher education creates a context that frames education as a commodity, underpinning the social roles of educators as the gatekeepers of student success (). Positioning students as customers has resulted in educators simplifying the learning experience, focusing on customer satisfaction instead of championing learning possibilities and growth (). This positioning creates a depersonalized educational experience with limited opportunities to build nourishing relationships. In this study, we all described feeling stretched thin due to a lack of resources, time, and opportunities to form meaningful connections with fellow educators and students. We believe this context adversely affected our experience as educators and limited student engagement and learning.

If underfunded programs continue to direct educators to select scalable and resource-light methods of learning and assessment, there is a missed opportunity to foster and generate contextual and experiential modes of learning and assessment that center relational collaboration (). Furthermore, reducing the classroom experiences to lectures and standardized evaluations upholds detrimental power hierarchies, placing educators in positions of power to determine student outcomes, with adverse outcomes on student well-being and learning (). We students described this power when we shared how achieving good grades is a currency to foster connection to educators. When education is positioned as transactional, higher education becomes the transfer of knowledge and skills from educator to student (; ). As understood through relational cultural theory, this one-way transaction overlooks the importance of connection and empathy needed in reciprocal student–educator relationships to foster mutual growth and learning (). For example, if educators include a relational exchange of feedback as part of their assessments, greater opportunity for learning and connection is offered through the social exchange of subjective experiences ().

While acknowledging that educators hold the bulk of the power in learning environments, the transactional nature of education left us educators sometimes feeling anxious when teaching or meeting a new cohort of students. We had to mitigate these nerves to remain connected and authentic. Our willingness to be vulnerable reminded us that educators and students alike may often be just doing their best to humanize their social roles and shared experiences in educational spaces. Anxiety and fear of taking chances and making mistakes were expressed by us all and identified as a symptom of the power structures perpetuated by the hegemony of higher education. Creating time to connect and engage in meaningful ways can be difficult to achieve if the curriculum is reduced to a checklist of weighted assignments that evaluate student competency (). Students as partners in higher education is a growing area of practice, which can realize favorable outcomes for students and educators (). If students and educators can collaborate in a similar way, they can carve out educational goals for relational, collaborative learning. Prioritizing the relation within occupational therapy education can be especially impactful for the success and well-being of minoritized students (; ), including racialized, disabled, first-generation, and 2SLGBTQIA+ students. This prioritization is critical given the long-overdue diversification of the health profession student body (). However, it is important to note that educators and students who are minoritized experience people, spaces, and institutions that are not safe and indeed are violent (; ), which can limit their ability to teach and learn relationally. Furthermore, oppressive normed notions of what an educator should be/look like/act like can erase minoritized dimensions of oneself when minoritized educators practice relational pedagogy through TUS (S. Mahipaul, personal communication, June 18, 2024).

Despite these challenges in higher education, we found that TUS can offer hope in redefining occupational therapy education as collaborative and mutually generative. TUS as a relational pedagogy emphasized for us authenticity, power equity, critical reflexivity, and empathy. TUS holds potential as a transformative relational pedagogy that aligns closely with critical and relational pedagogies. bell ) emphasized the critical importance of teaching in an engaged, respectful, and caring way, where educators and students are valued as whole beings to create genuine, reciprocal learning where all students can thrive. The findings of this study echo hooks’ clarion call for radical change in higher education that centers on collective humanity and unabashedly reimagines higher education.

Radical empathy, as discussed by through a relational cultural theory lens, is a concept which looks at the dynamic and powerful role that educators play in the lives of students. Much like TUS, radical empathy is the exchange and growth between student and educator, feelings of validation, and the widening of our understanding of ourselves and one another (). In our findings, the experience of TUS brought about a similar exchange, creating a generative awareness of one another. We experienced enhanced levels of authenticity and change within ourselves through a mutually empathic understanding of each other. This enhanced authenticity required dedicated energy to learn about both ourselves and each other and to continue to reflect on who we are and what we value (). Given how prevalent TUS is within occupational therapy practice, it holds exciting promise for occupational therapy educators to lead meaningful, relational transformation in occupational therapy education. TUS is intentional, deliberate, and intended to generate relationships through authenticity; those who understand and use TUS know it is a reciprocal and active exchange.

Our findings also spoke to how TUS as a pedagogy can create shifts in how we engage in life beyond the classroom—a transformative force beyond learning environments. suggest that when educators model the therapeutic relationship and associated TUS techniques in the classroom, students may “acquire the skills to act in a similar fashion” (p. 50) beyond the classroom. This transformation is especially resonant for student occupational therapists where care in education could extend to care in practice. By taking bold and brave steps, educators can use TUS to codesign occupational therapy education with students as partners, prioritize space and time for reflexive relationality and power-sharing, and work to normalize these experiences in higher education and beyond.

Considerations

Given the relational and personal methodology and methods of this study, it is difficult to determine how the inability to connect in person due to geographical limits and the COVID-19 pandemic restrictions in place at the time of the study affected our group dynamics, discussions, and findings. Yet, completing this study during the COVID-19 pandemic was also a unifying experience that created connections through collective experiences. Furthermore, our social identities shaped this study, including discussions and data analysis, and so it is likely that our identities also limited the study. Lastly, we engaged in methodological borrowing from collaborative autoethnography, and while this methodology enhanced our qualitative description study, the transformative potential of collaborative autoethnography, through centering raw, evocative personal narratives, was not achieved.

Conclusion

Implementing TUS as a relational pedagogy and challenging status quo power structures in higher education is still very much a work in progress. The business of education generates oppressive power hierarchies that do not prize relationships and collaboration to promote reciprocal growth and learning between students and educators. TUS was shown to challenge these dynamics and foster mutuality, empathy, authenticity, and care in learning environments and beyond. Future studies may consider exploring the specifics of how TUS is pragmatically applied as a relational pedagogy and the application and effectiveness of TUS in other health, healing, and caring professions programs, through a diversity of educator and student perspectives. We call on educators and administrators in occupational therapy education to engage in the bold, brave, and necessary work of dismantling systems of oppression in higher education to realize places of learning that celebrate our shared humanity.

Key messages

With TUS being a foundational occupational therapy practice skill, occupational therapy educators and students have a distinct opportunity to enact relational teaching and learning.

TUS can facilitate a shift in student–educator interactions, away from extractive and transactional relationships and toward authentic and caring relationships that enhance learning and mutual growth.

Program and institutional-level supports are required for occupational therapy educators to meaningfully implement relational pedagogies like TUS, given the systemic de-relationality of neoliberalist higher education.

Acknowledgments

This study took place on the ancestral, traditional, and occupied lands of the xməθkəyəm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwəta[Latin Small Letter L With Belt] (Tsleil-Waututh) Nations, on what is colonially known as Vancouver, and the Huron-Wendat, the Seneca, and the Mississaugas of the Credit, on what is colonially known as Toronto. We are deeply grateful to the Indigenous stewards of these lands since time immemorial and we commit to the continued work of truth and reconciliation in what is now Canada. We have learned so much, and continue to learn, about the relational from Indigenous scholarship on Indigenous pedagogies (see ; ) and Indigenous epistemology (see ). We are also grateful to the reviewers for their helpful comments and encouragement. Lastly, we would like to thank Dr. Susan Mahipaul for her generosity of time, expertise, knowledge, and guidance as we shaped our methodology.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD Katie Lee Bunting https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4980-4339

References

- Adams K. L. (2018). Relational pedagogy in higher education [Doctoral dissertation, University of Oklahoma]. SHAREOK.

- Anderson V., Rabello R., Wass R., Golding C., Rangi A., Eteuati E., Bristowe Z., Waller A. (2020). Good teaching as care in higher education. Higher Education, 79(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00392-6

- Baice T., Fonua S. M., Levy B., Allen J. M., Wright T. (2021). How do you (demonstrate) care in an institution that does not define ‘care’? Pastoral Care in Education, 39(3), 250–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02643944.2021.1951339

- Beagan B. L., Sibbald K. R., Pride T. M., Bizzeth S. R. (2022). Professional misfits: “You’re having to perform . . . all week long”. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 10(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1933

- Bennett T. (2018). Pedagogic challenges to the hegemony of neo-liberal business and management teaching. In A. Melling & R. Pilkington (Eds.), Paulo Freire and transformative education: Changing lives and transforming communities (pp. 43–56). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-54250-2

- Bradshaw C., Atkinson S., Doody O. (2017). Employing a qualitative description approach in health care research. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 4, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393617742282

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brown M. E. L., Horsburgh J. (2022). I and thou: Challenging the barriers to adopting a relational approach to medical education. Medical Education, 56(1), 14–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.14691

- Byrne D. (2021). A worked example of Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis. Quality and Quantity, 56, 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s1135-021-01182-y

- Caraballo L., Soleimany S. (2019). In the name of (pedagogical) love: A conceptual framework for transformative reaching grounded in critical youth research. Urban Review, 51(1), 81–100. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-018-0486-5

- Chang H., Ngunjiri F., Hernandez K.-A.C. (2013). Collaborative autoethnography (Book Series: Developing Qualitative Inquiry). Routledge.

- Charmaz K. (2015). Teaching theory construction with initial grounded theory tools: A reflection on lessons and learning. Qualitative Health Research, 25(12), 1610–1622. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315613982

- Chrona J. (2022). Wayi wah! Indigenous pedagogies: An act of reconciliation and anti-racist education. Portage & Main Press.

- Coia L., Taylor M. (2013). Uncovering our feminist pedagogy: A co/autoethnography. Studying Teacher Education, 9(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2013.771394

- Corbin J., Strauss A. (2008). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (3rd ed., pp. 229–246). Sage.

- Cranton P., Carusetta E. (2004). Perspectives on authenticity in teaching. Adult Education Quarterly: A Journal of Research and Theory, 55(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741713604268894

- Curran R. (2017). Students as partners—Good for students, good for staff: A study on the impact of partnership working and how this translates to improved student-staff engagement. International Journal for Students as Partners, 1(2), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.15173/ijsap.v1i2.3089

- Deneen C. C., Prosser M. (2020). Freedom to innovate. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 53(11), 1127–1135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1783244

- Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. (2005). Introduction: The discipline and practice of qualitative research. In Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research ((3rd ed., pp. 1–32). Sage.

- Freire P. (2018). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Bloomsbury Academy.

- Gourlay L., Stevenson J. (2017). Teaching excellence in higher education: Critical perspectives. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(4), 391–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2017.1304632

- Gravett K., Taylor C. A., Fairchild N. (2021). Pedagogies of mattering: Re-conceptualising relational pedagogies in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 29(2), 388–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1989580

- Gravett K., Winstone N. E. (2022). Making connections: Authenticity and alienation within students’ relationships in higher education. Higher Education Research and Development, 41(2), 360–374. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1842335

- Guba E. E., Lincoln Y. S. (2005). Paradigmatic controversies, contradictions, and emerging confluences. In Denzin N. K., Lincoln Y. S. (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research ((3rd ed., pp. 191–216). Sage.

- Haertl K. (2008). From the roots of psychosocial practice-therapeutic use of self in the classroom: Practical applications for occupational therapy faculty. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 24(2), 121–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/01642120802055168

- Harden J. (2017). The case for renewal in post-secondary education. Policy Alternatives. https://policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/National%20Office/017/03/Case_for_Renewal_in_PSE.pdf

- Haverkamp B. E., Young R. A. (2007). Paradigms, purpose, and the role of the literature: Formulating a rationale for qualitative investigations. The Counseling Psychologist, 35(2), 265–294. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006292597

- hooks b. (1994). Teaching to transgress. Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203700280.

- Jordan J. V. (2000). The role of mutual empathy in relational/cultural therapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56(8), 1005–1016. http://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(200008)56:8<1005::AID-JCLP2>3.0.CO;2-L

- Jordan J. V., Schwartz H. L. (2018). Radical empathy in teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2018(153), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20278

- Kinchin I. M. (2022). Care as a threshold concept for teaching in the salutogenic university. Teaching in Higher Education, 27(2), 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1704726

- King E., Cartney P. (2023). Teaching partnerships in neoliberal times: Promoting collaboration or competition? Practice, 35(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503153.2022.2106359

- Lapadat J. C. (2017). Ethics in autoethnography and collaborative autoethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(8), 589–603. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417704462

- Matthews K. E., Dwyer A., Russell S., Enright E. (2019). It is a complicated thing: Leaders’ conceptions of students as partners in the neoliberal university. Studies in Higher Education, 44(12), 2196–2207. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2018.1482268

- McKnight A. N. (2008). Institutions of schooling, systemic prescriptions, and emotional discord: Toward pedagogies of relational meaning. Interchange, 39(3), 351–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10780-008-9070-3

- McPhail-Bell K., Redman-MacLauren M. L. (2019). A co/autoethnography of peer support and PhDs: Being, doing, and sharing in academia. The Qualitative Report, 24(5), 1087–1105. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2019.3155

- Mosey A. C. (1986). Psychosocial components of occupational therapy. Raven Press.

- Motta S. C., Bennett A. (2018). Pedagogies of care, care-full epistemological practice and ‘other’ caring subjectivities in enabling education. Teaching in Higher Education, 23(5), 631–646. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2018.1465911

- Nyumba T. O., Wilson K., Derrick C. J., Mukherjee N. (2018). The use of focus group discussion methodology: Insights from two decades of application in conversation. Methods in Ecology and Evolution, 9(11), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12860

- Ohito E. O. (2019). “I just love black people!”: Love, pleasure, and critical pedagogy in urban teacher education. Urban Review, 51(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11256-018-0492-7

- Ormiston T., Green J., Aguirre K. (Eds.) (2020). S’tenistolw: Moving Indigenous education forward. JCharlton Publishing Ltd.

- Polatajko H. J., Davis J. A., McEwen S. (2015). Therapeutic use of self: A catalyst in the client-therapist alliance for change. In Christiansen C., Baum C., Bass-Haugen J. (Eds.), Occupational therapy: Performance, participation, and well-being (4th ed., pp. 81–92). Slack.

- Pololi L., Conrad P., Knight S., Carr P. (2009). A study of the relational aspects of the culture of academic medicine. Academic Medicine, 84(1), 106–114. httpsss://doi.org/http://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181900efchttps://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181900efc

- Punwar A. J., Peloquin S. M. (2000). Occupational therapy: Principles and practice (3rd ed.). Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Razack S., Naidu T. (2022). Honouring the multitudes: Removing structural racism in medical education. The Lancet, 400(10368), 2021–2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02454-0

- Sandelowski M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description?. Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:43.0.co;2-g

- Sandelowski M. (2010). What's in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(1), 77–84. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20362

- Schwartz H. L. (2017). Sometimes it’s about more than the paper: Assessment as relational practice. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 28(2), 5–28.

- Schwartz H. L. (2019). Connected Teaching. Stylus.

- Scotland J. (2012). Exploring the philosophical underpinnings of research: Relating ontology and epistemology to the methodology and methods of the scientific, interpretive, and critical research paradigms. English Language Teaching (Toronto), 5(9), 9. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v5n9p9

- Su F., Wood M. (2023). Relational pedagogy in higher education: What might it look like in practice and how do we develop it? International Journal for Academic Development, 28(2), 230–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2023.2164859

- Taff S. D., Grajo L. C., Hooper B. (2020). Perspectives on occupational therapy education: Past, present, and future (1st ed.). SLACK.

- Taylor R. R., Lee S. W., Kielhofner G., Ketkar M. (2009). Therapeutic use of self: A nationwide survey of practitioners’ attitudes and experiences. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 63(2), 198–207. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.63.2.198

- Tolich M. (2010). A critique of current practice: Ten foundational guidelines for autoethnographers. Qualitative Health Research, 20(12), 1599–1610. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732310376076

- Varpio L., Martimianakis M. A., Mylopoulos M. (2022). Qualitative research methodologies: Embracing methodological borrowing, shifting and importing. In Cleland J., Durning S. J. (Eds.), Researching medical education (2nd ed., pp. 115–125). Wiley-Blackwell.

- Wang D. (2012). The use of self and reflective practice in relational teaching and adult learning: A social work perspective. Reflective Practice, 13(1), 55–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2011.616887

- Wilson S. (2008). Research is ceremony: Indigenous research methods. Fernwood Publishing.