Introduction

In school-based occupational therapy, collaboration between educators and school occupational therapists (OTs) is fundamental in any service delivery model for students presenting with special needs who are integrated with inclusive schools. Tiered models offer a continuum of services to support students with special needs—where tier one offers universal programming to benefit all students, tier two includes targeted group interventions and tier three emphasizes individualized support (). OT–educator collaboration is essential for successfully implementing tiered service models, including rehabilitative services (). For instance, tiered models such as Response-to-Intervention (RtI) and Partnering for Change (P4C) are known to have benefits such as greater student participation, decreased number of referrals for special education interventions, improved teacher engagement in professional development, and increased collaboration in school teams (; ; ; ; ).

Despite positive outcomes and evidence supporting tiered service models that are collaborative, implementation challenges remain. Although OTs and teachers agree that collaboration is important and necessary (), studies involving OTs and teachers reveal barriers to these collaborative relationships (; ; ). These include teachers’ confusion over the OT role, limited communication opportunities, and teachers’ desire for OTs to increase awareness of classroom constraints (). Additionally, professionals may not be adequately skilled or knowledgeable about teamwork collaborative processes to support young students (). Collaboration involves trust, clear communication, mutual respect, conflict resolution, shared goals, active participation, and shared decision-making (). These factors are highly contextualized and must be carefully considered when examining service delivery in local education settings, as well as in the development of knowledge translation (KT) interventions aimed at improving collaborative practice, as recommended in the literature (; ).

In Québec, education policy supports the inclusion of children with special needs in local schools (), but challenges remain in organizing services for their integration (). School service centers allocate funding based on a coding system tied to specific diagnoses, reflecting a medical model of referral-based services (). Initially, school-based OT services followed this model, with referrals based on individual needs (e.g., motor, sensory, emotional) or consultative support (e.g., accommodations) (; ). However, the high volume of referrals makes it difficult to meet students’ needs (; ). The provincial education ministry is shifting towards tiered models to better support inclusion (). Recent research highlights the benefits of increased collaboration, coaching, staff training, and school-wide inclusive practices within these models (). This shift calls for a reassessment of service delivery approaches and collaborative practices.

Previous research shows that preschool teachers in Québec may lack full knowledge of the OT role in schools (). Emerging evidence supports tiered services, with tier-one support (e.g., workshops, consultations) relying on school team collaboration and capacity-building (). Effective tiered services depend on collaboration, capacity-building, and curriculum-relevant, authentic services (). Future research is needed to explore and advance collaborative teamwork in school OT practice (; ). While OT support extends to all school team members, this study focuses on OT–teacher collaborations.

This qualitative descriptive study is the first phase in a larger, two-phase project. The findings from this first phase will inform the development of a knowledge translation (KT) intervention, the second phase, aimed at optimizing collaboration among OTs and teachers. To provide a more nuanced and in-depth exploration of how collaboration occurs between occupational therapists and teachers in Québec elementary schools, this study aims to explore the perspectives on current and ideal collaborative practices and associated contextual barriers and facilitators within their local school settings. In addition, perspectives on preferred learning strategies and methods to optimize collaboration were elicited to inform future KT interventions.

Methods

The overall project (first and second phases) follows a sequential embedded design (), where the first phase (i.e., this study) utilizes qualitative methods, followed by the second intervention phase, which will incorporate quantitative and qualitative methods. Ethics approval for both phases was obtained by the Research Ethics Board at McGill University.

In this qualitative descriptive study (), two focus groups were conducted: one with elementary school teachers (n = 6) and one with school OTs (n = 5). Focus group methods were used as they allowed participants to discuss various topics and share their satisfaction and/or dissatisfaction with services (). This also allowed them to identify differences and similarities in opinions and perspectives, to shed light on their realities, and to explore “what they really think” (, p. 494; ).

The 2-h focus group sessions, facilitated by the first author (LI), were conducted via Microsoft Teams due to COVID-19, enabling greater participant engagement across school boards and service centers. A 10-question guide structured the discussion (see Appendix A). Questions related to barriers and facilitators were developed by drawing on elements of behavioral change and the determinants of successful collaboration by and by the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) (), to identify factors influencing collaboration and the factors that would need to change to improve collaboration. The research team (A4 and A2), who have extensive experience in KT research in school-based settings, reviewed and provided feedback on the focus group guide.

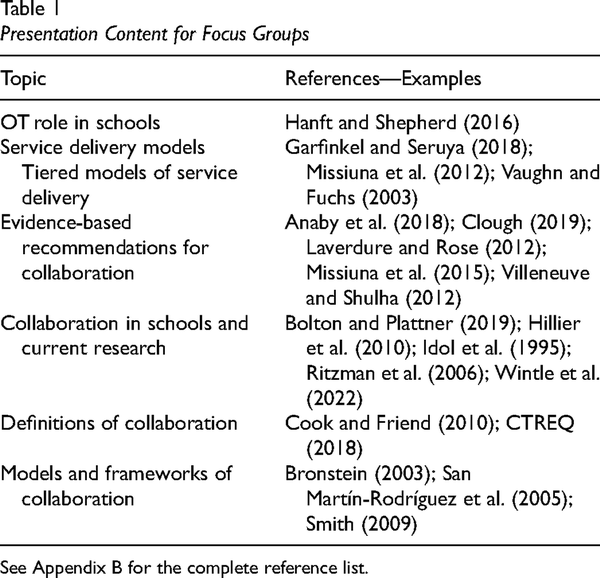

A 20-min presentation was provided at the onset of the focus group discussion to introduce the topic of collaboration and initiate the dialogue. Please refer to Table 1 for a summary of the topics presented and corresponding references. Both groups received the same presentation. Due to language preferences, the teacher presentation was offered in English, and the OT presentation was provided in French.

Inclusion Criteria and Recruitment

Participants were OTs and teachers from southern Québec public schools, including rural, suburban, and urban settings, within both English and French school boards. OT and teacher participants with less than 1 year of experience were excluded. Convenience sampling was used for recruitment: teachers were contacted via union newsletters, while OTs were recruited through social media ads and emails to a network of Québec OTs. All interested participants meeting the criteria were included.

Data Collection and Analysis

Written and verbal consent was obtained from all participants. Using LimeSurvey, they completed a brief demographic survey about their work experience. Focus groups were recorded via Microsoft Teams and transcribed. Each participant was assigned an anonymized ID. Thematic analysis followed steps, with an inductive approach staying “close to the data” to identify key patterns in participants’ accounts, experiences, views, and beliefs ().

The first author and a research assistant (RA) independently coded the two focus group transcripts. A first meeting was held to discuss initial codes for the first half of both transcripts. Then, the remainder of the transcripts was coded, and a subsequent meeting was held. A codebook was compiled. The first author and the RA independently categorized codes into overarching initial themes. Meetings were held to discuss the thematic categories and to reach a consensus on a list of final themes, which were then reviewed with the research team.

The first author has work experience as a school OT and engaged in reflexivity of biases, beliefs, and experiences throughout the coding process (). Both coders have experience with conducting qualitative research in the field of rehabilitation and worked in interdisciplinary teams. The quotes from the French-speaking participants were translated to English for this paper.

Results

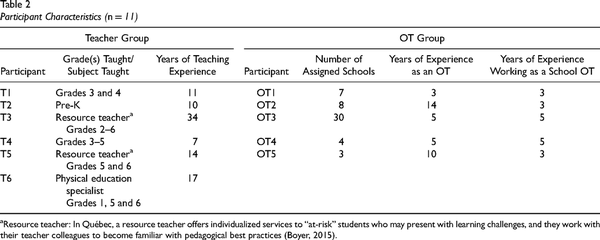

Participant Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes participant characteristics. The teachers worked in predominantly English-language schools. In the OT group, four OTs worked in French-language schools and one OT worked in English-language schools. All participants worked in schools located in southern Québec regions. The number of schools assigned to each OT ranged from 3 to 30 schools, with varying service delivery models also reported.

Themes

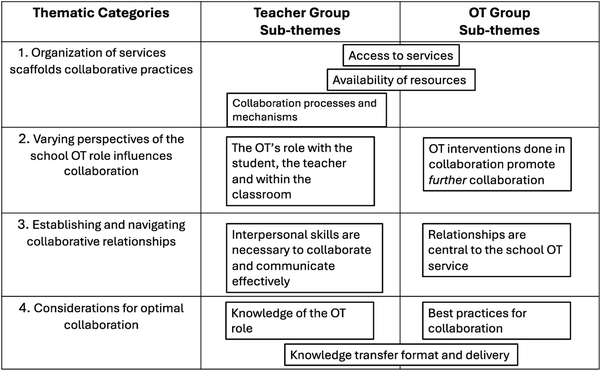

A total of four thematic categories were generated from the focus group discussions: (a) Organization of services scaffolds collaborative practices; (b) varying perspectives of the school OT role influence collaboration; (c) establishing and navigating collaborative relationships; and (d) considerations for optimal collaboration. Please see Figure 1.

Organization of service scaffolds collaborative practice

Figure 1

Thematic categories and sub-themes.

This thematic category describes the organization of services, that is how services are accessed and rendered, according to the experiences of the OT and teacher participants. There are three sub-themes within this category. Two themes were common to both the OT and teacher groups: (a) Access and delivery of services and (b) availability of resources. One theme was unique to the teacher group: (c) Collaboration processes and mechanisms. The teachers expressed that although they appreciate having OT services and recognize the importance of OT in schools, accessing such services can be challenging and confusing as referral procedures (e.g., forms to complete) or special education guidelines are not always clear, even at a provincial level:

It would be nice if the guidelines were similar across Quebec, that everybody knows the same procedures and we followed them. (T3)

Access to services

Additionally, access may be influenced by a lack of knowledge about the roles and services offered by various professionals (e.g., school psychologists, speech-language pathologists, and OTs). As one teacher stated, “a lot of teachers don’t even know what they are looking for” (T6).

Teachers and OTs discussed how services are organized, which guides the referral process and influences the extent of collaboration. For instance, teachers often stated that “OTs are spread so thin” as they travel to multiple schools, thus presence is infrequent. The teachers described the main role of the OT is to evaluate students individually, which can limit collaborative interactions due to the lengthy waitlists and limited or inconsistent follow-up visits. OT intervention in the class in the form of activities/lessons was reported by teachers to be infrequent. Additionally, teachers reported that although students with higher priorities may have access to OT services through the referral process, other students with less significant needs may not necessarily benefit. Contrarily, in instances where OT presence was consistent and regular, this was reported to enhance the overall communication between OT and school staff and clarify referral procedures. To support the organization of services, having an ‘ally’ or a person responsible in the school who understands the school professionals’ roles, such as the resource teacher or special education teacher, can help to establish wait-list priorities.

Similarly, the OTs often alluded to how organization and delivery of services within their school boards/service centers shape the delivery of services, their in-school presence, and thus the scope of collaborative practices. Among the group, the number of schools assigned per OT varied (i.e., 3[FIGURE DASH]30 schools per caseload). This variation not only affects how services are rendered but also the frequency of collaboration with teachers and staff. One OT expressed, “out of sight, out of mind” for how important in-school presence was for her (OT1). In-school presence also supports teachers’ understanding of the OT role. Maintaining the same assigned schools year after year was reported to help sustain collaborative relationships and enhance the knowledge of OT services.

The OTs generally described their service mandate using a school-wide or classroom-wide approach, rather than an individualized approach. For example, one OT (OT2) stated she adopts “a more response-to-intervention approach.” Another OT (OT1)

described how she designated ‘OT time’ in the teachers’ schedules and this was helpful in maintaining communication and follow-up with the teachers:However, most OTs described scheduling school visits as challenging due to the number of assigned schools. In general, having professional autonomy to flexibly adapt their schedule to accommodate school visits/meetings was viewed as favorable to fostering collaborative relationships and their offer of service. Availability of resources was discussed in both groups, primarily as a challenge regarding time and budgets. Both teachers and OTs reported insufficient time to meet and discuss cases or share ideas. Participants in both groups stated discussions are often held in the doorway or hallway, which impacts how strategies, tools, or plans are implemented because “it's just not organized officially” (T4), which was also echoed in the OT group:

Teachers can “place” me in their schedule as a specialty. I do prevention, health promotion, and coaching teachers…It's helpful in the class. (OT1)

One of the organizational things that help is to liberate teachers and to give them time for workshops/trainings. (OT3)

Availability of resources

OTs also reported lacking time to follow up with classes or students or to implement coaching/mentoring strategies. Accordingly, funds to release teachers to attend meetings (i.e., to hire replacements) are needed for collaborative exchanges to occur. Protected meeting time was described as important for both OTs and teachers to allow for exchanges to take place. However, the time and money “is just not there” (T6). Regarding capital resources, the OTs agreed that if there were more OTs employed by their school service center, this would result in fewer school assignments per OT, and thus afford increased OT visibility in the schools. In addition, both OTs and teachers reported funds are needed to purchase OT-recommended tools and equipment. The teachers discussed the processes and mechanisms to collaborate, which refers to the tools and mechanisms of collaboration—the “who, when, where, and how” of working collaboratively.

Collaboration processes and mechanisms.

Teachers reported collaborative exchanges typically involve the teacher and OT. However, they emphasized that support staff (e.g., classroom attendants) and parents are often not included in these meetings or discussions—and should be. “When” and “where” collaboration occurs were frequently mentioned as barriers. Arranging a time for the teacher and OT to meet was deemed a frequent challenge:

You only get them so often and it's like a quick “in the hallway” chat. There's no time to sit and meet or even to implement everything they want because it's just not organized “officially.” (T4)

Suggestions such as knowing the professionals’ schedules in advance, meeting the OT at the beginning of the year to “discuss bigger cases” (T6), and regular communication were shared to support collaboration. “How” collaboration occurs, such as the communication tools and mechanisms, was also discussed. Written communication, such as e-mail, reports, completing questionnaires, and summaries of plans or recommendations, was appreciated by the teachers. The use of virtual meetings was mentioned as an efficient way to collaborate, e.g.,:

We have a good collaborative approach with our school board and our consultants. We meet on a regular basis—due to COVID and using Microsoft Teams, we were able to meet more often. We don’t have to worry about them traveling from school to school. (T3)

Varying perspectives of the school OT role influence collaboration

The organization of services, as described, reveals how the mandate and delivery of services can also influence the perception of the OT role from teachers and OTs. The teacher sub-theme indicated from the discussion described the role of the OT in the classroom, with the student, with the teacher, and within the school. The OT sub-theme focused mainly on collaborative-based interventions and how these services cultivate further collaboration within the school team. Teachers reported the primary OT mandate is to observe and carry out assessments with the students, whereby recommendations are provided for the teacher and personnel to implement, typically outlined in a report. The OTs also assist by confirming or ruling out causes of a student's difficulty he/she is experiencing in the class. However, due to the OTs’ workload, availability, and schedule, continuous collaborative consultation following an evaluation is lacking, as described by one teacher:

There's a lot on evaluation, but what do you do afterwards? You have recommendations, but how do you implement them? (T3)

The OT’s role with the student, the teacher, and within the classroom

There was an expressed need for additional opportunities for teacher-OT discourse to implement proposed recommendations. One teacher appreciated consulting the OT's written report to help support a student. In situations with frequent interactions with the OT following the assessment, teachers perceived this as helpful as they can “spot-check” with the OT as needed (T6).

OT interventions with the teachers/staff included: providing workshops to the school personnel (e.g., a workshop about gross motor skills); sharing feedback with teachers; or modeling strategies in class while the teachers observe. These practical interventions were viewed positively by all students in the class: The OT group primarily described interventions that were done in partnership with teacher colleagues and the roles they assumed to facilitate these collaborative relationships. Examples include: partaking in meetings; OT–teacher knowledge exchange; the OT's role as a consultant, coach, or co-teacher; and assuming responsibilities beyond the OT role.

I think I’ve always appreciated when the professionals understand the environment that we’re working in. When they ask me to do certain exercises with a student, but they suggest to try them with all students. It's a way to get the student who the exercise is intended for, but they are all going to benefit. Just the fact that they understand I’m not working one-on-one, that I have 25 to 30 students in my class. (T6)

OT interventions done in collaboration promote further collaboration

OT–teacher meetings were generally described as important for communication and sharing. They are opportunities for teachers to discuss student concerns, ask questions, build strategies together, exchange information, and develop relationships.

OT–teacher knowledge exchanges, such as OTs offering workshops, were described to potentiate collaboration. Two OTs spoke positively about opportunities for teachers to attend OT professional development workshops or to participate in communities of practice (COPs). These workshops or COPs are occasions to share information, model strategies and address students’ skillsets that are important to teachers (e.g., printing and writing). The OTs stated workshops allow them to reach numerous individuals simultaneously. They also serve as a reference when teachers describe concerns to the OT. One OT expressed that when teachers and staff have been exposed to the same workshop, this can lead to a “common language” (OT1).

The OTs further described their roles as consultants and co-teachers in jointly developing activities with teachers to build capacities. When partaking in this co-teaching or coaching relationship, OTs shared that teachers selected the goals and the ‘local’ in-class materials were used, as described:

We did co-teaching about writing skills as a team. I wasn’t just an expert, they were experts of “their side.” We were all experts in our own domains. I found [this approach] facilitated the work within this team. (OT5)

The OTs spoke about the various roles they take on that go beyond the scope of OT practice. One OT stated she is “there to help”, regardless of her OT role to facilitate her sense of belonging in the school. Partaking in social activities was also described to deepen connections with colleagues further:

I participate in social activities. Sometimes I will get out of my role, I find that we have a role in community practice…We leave a bigger trace in the school when we participate in school life. (OT1)

Establishing and navigating collaborative relationships

This thematic category addresses the interpersonal aspects of collaborative relationships, highlighting the relational complexities inherent in these interactions. Teachers discussed the interpersonal skills needed during interactions with OTs and other professionals. They emphasized the importance of knowing who the OT is and establishing a relationship; these were regarded as significant collaboration facilitators. For instance, one teacher (T6) noted that having “a face to a name” and ensuring staff awareness of the assigned OT could enhance collaboration. Teachers may feel comfortable and willing to approach the OT to start a conversation. Additionally, the communication and delivery of information from a professional was deemed as important by teachers, as described:

The feedback I get from other teachers is when professionals are coming into the class, they sometimes feel judged. There is this impression that what they’re doing may be wrong. So, I think the wording and the communication that they use is very important. (T5)

Interpersonal skills are necessary to collaborate and communicate effectively

Trust was reported as paramount to feeling comfortable and willing to approach the OT for support. Trust was reported to be built after several years of working with the same OT and was stated to facilitate communication and interactions. The OTs frequently emphasized the importance of building connections with staff and fostering relationships as initial goals for their services. Like the teachers, they also discussed interpersonal relationship skills. However, the focal point in the OT discussion regarded these relationships as central to their service delivery.

Relationships are central to the school OT service

OTs reported that understanding the school culture and connecting to school staff as allies facilitates collaborative practices. OTs spoke about their relationships with school principals as leaders who can guide the teamwork dynamics among staff, as described by one OT:

The administration has a large impact. They back me up. They understand my role and call upon me at the right time […] They know if I have a say in a case. She will write to me, “I want you to be at the meeting”—to invite me to an intervention plan [meeting] for a student. (OT1)

The OTs also discussed the links they created with teachers—even caretakers. They expressed that connecting to someone familiar with the school facilitates their integration into the school. The allies can be messengers, share pertinent information, manage cases and provide updates, support the implementation of OT recommendations, and advocate the benefit of OT services through word-of-mouth.

Interpersonal skills such as using appropriate, transparent, and clear communication, developing a sense of trust, being curious, and having a dynamic and adaptable attitude were discussed as facilitating skills in the relationship. The OTs also shared how teachers’ open-mindedness and communication styles can impact the implementation of OT interventions. They described how their role as an “expert” can evolve throughout the relationship:

We will be experts at the beginning for some. For others, we will be completely collaborative. They like not having a recipe. We may start off as experts because that is what they need, and after that, we split [roles] and adapt our position. (OT1)

The OTs considered the professional backgrounds of the teachers. To further strengthen this bond of trust, they discussed reflecting on their values, attitudes, perceptions, and understanding of the teachers’ realities and priorities, as one OT indicated:

I really try to understand their reality, their stress, the academic requirements, the team dynamic, and all that. And then to adjust my expectations. (OT2).

Considerations for optimal collaboration

Both groups provided suggestions and considerations about collaboration and optimizing collaborative practice. Three sub-themes were generated: one teacher sub-theme, ‘Knowledge of the OT role’; one OT sub-theme, ‘Best practices for collaboration’; and one sub-theme common to both groups, “Knowledge transfer format and delivery.” Teachers expressed certain knowledge needs, such as acquiring a deeper understanding of the OT role, learning ‘how to flag certain behaviors’ (T2) for early intervention, and understanding the rationale for using specialized tools. One teacher stated learning about the “practical things” that could be implemented by the teacher before OT intervention as lengthy wait-times delay services (T2). Teachers proposed observing and modeling an OT, where they “get to see the OT in action” (T3), which could be helpful. This could further afford a learning opportunity to reflect on while in context. The OTs voiced learning about the “best practices” and the “little how-to's” on how to collaborate with teachers. For instance, learning about school-relevant coaching skills and strategies to engage a teacher-partner who may be less inclined to collaborate. Optimizing communication skills, such as learning to ask the right questions, was also indicated as an OT knowledge need. The OTs discussed the challenge of integrating within the school culture due to the different educational backgrounds of OTs and teachers, i.e., healthcare and education. As one OT described:

“To understand ‘planet education’… we have to readjust [ourselves] because our background is very different. I find that to adapt the language, it's not entirely obvious.” (OT2)

Knowledge of the OT role

Best practices for collaboration

Knowledge transfer format and delivery

Regarding format, both teachers and OTs agreed that workshops to optimize collaboration should involve OTs, teachers, and other staff and professionals. Teachers emphasized the need for active engagement in workshops, while follow-up sessions could allow for practice, reflection, sharing feedback, and reinforcement of new learning to see “what worked well and what didn’t” (T3). One OT suggested offering collaboration-focused learning sessions to university students in OT and education programs. Another OT proposed team-building exercises outside of the work setting to informally foster collaborative relationships.

Discussion

This qualitative descriptive study aimed to explore the current and ideal collaborative practices and associated contextual barriers and facilitators related to collaboration among elementary school teachers and school-based OTs working in southern Québec mainstream schools.

In the context of delivering occupational therapy services in this province, a notable contrast emerged between the discussions of teachers and OTs. This highlights the diverse landscape of service delivery models used across different school boards and service centers (). The teachers predominantly alluded to a traditional service delivery model in their schools. They perceived the OT's main role is to administer individualized assessments following a referral, which may lead to lengthy waitlists (). Both groups reported that the multiple school assignments impact collaboration negatively due to the inconsistent presence of OTs in school, which limits opportunities for exchanges and hinders the ability to provide timely services (; , ; ). To mitigate case management and promote the OT role in the school, both groups discussed the role of an “ally” to link the OT to the school. These allies (e.g., school principal, resource teacher, or special educator) can promote collaboration by explaining OT service mandates and including the OT in meetings (). There is little research on how OT–teacher collaboration can be facilitated via an ally in the school. However, case management has been identified in models of teamwork ().

In contrast to the teacher's reports of a traditional model of service delivery, the OTs seemed to recognize the need to employ a more collaborative, school-wide, or multitiered approach rather than adhering to an individual, referral-based model (). They collaborated with teachers on teacher-chosen topics (e.g., printing) or goals for class-wide needs. In addition, workshops, coaching or modeling-specific techniques, and consultation meetings with teachers were viewed as beneficial to fostering collaboration. Our findings further recommend, as indicated in previous literature, that OTs who target their services at this first tier appear to facilitate access to OT services, assist with OT exposure and advocacy, and promote the understanding of the OT role (; ). Although the teacher focus group mainly alluded to a referral-based model, these school-wide OT interventions were reportedly appreciated and viewed positively by teachers. They prefer to see the OT “in action” in the classroom, to have more opportunities to exchange and appreciate tools or strategies that, although intended for one student with special needs, could benefit all students, which has been previously reported (; ; ; ; ). These interventions consistently highlight the need for increased collaboration, capacity-building, and engagement of the OT in the school community and classroom context (; ).

Concepts related to relationship-building and the interpersonal skills needed to navigate collaborative work were reported by teachers and OTs. Feeling a sense of belonging and comfortable in the relationship were discussed by the OTs and teachers, respectively. For OTs, this sense of belonging is imperative to building their professional identity as school OTs (). For teachers, our results reflected prior research findings on how initiating a collaborative relationship may create feelings of insecurity (e.g., fear of being judged) (; ). The OTs reflected on their approaches and tried to understand the teachers’ realities, manage their expectations of teachers, ensure interventions are implementable, and instill trust by initiating communication, similar to previous research (; ; ; ). A snowball effect seems to occur; the more OTs share responsibilities with teachers and work in the classroom, the deeper and richer the collaboration becomes (), which was expressed by both groups in our study. The partnership between OTs and teachers not only strengthens collaboration but also expands the potential scope of school OT practice (; ). These interpersonal relationship skills are the basis for effective communication and for navigating various attitudes or practice styles (; ). Professional development to address and enhance these skills has been recommended (; ).

Regarding contextually based practice and research implications for collaboration in schools, our findings highlight the necessity to examine the service delivery models currently employed in Québec. This includes clearly defining the role of school OTs and recommending models that promote optimal collaboration (). For example, best practice guidelines have recommended adopting a workload approach versus a caseload approach, where services are predominantly provided in the classroom environment (). Moreover, role descriptions of school professionals and procedural guidelines, at both the provincial and school levels, need to emphasize collaborative teamwork (). Confusion or poor understanding of the OT service mandate, what OTs do (or can do), may influence teachers’ perceptions as well as their inclination to initiate a collaborative relationship (; ).

Furthermore, in research, key contextual ideas to inform the development of a tailored KT intervention on school collaboration have also been identified. Both teachers and OTs agreed professional development initiatives should consider jointly held sessions, where OTs, educators, professionals, and support staff can attend. Accordingly, such joint training opportunities should include active engagement and reflection in KT sessions and mentoring, which are recommended strategies to enhance collaborative practices (). However, future research is needed to determine the extent to which such KT strategies can optimize collaboration between teachers and OTs, as well as improve student outcomes.

Limitations

Differing perspectives emerged as the OTs and teachers worked in various school boards and language settings, with teachers primarily in English-language schools and most OTs in French-language schools. The organization of services and mandates can vary significantly across these settings. However, the small convenience sample, which included two focus groups, may not adequately reflect the broader collaboration practices between OTs and teachers in inclusive schools in Québec. To enhance the credibility of the results, member checking could have improved their trustworthiness. To address this, several discussions were held with the research team. Themes were revisited with the original data to ensure that the thematic map accurately represented the intended meaning of the discussions.

Conclusion

In Québec, as the OT role evolves, various factors at the organizational, school, and interpersonal levels impact collaboration between OTs and teachers. Our study highlighted the need for clearly defined OT roles across a continuum of services, from school-wide to individualized; procedural guidelines that promote teamwork; involvement of school leaders or allies to support collaboration; and strong interpersonal skills to build effective partnerships. To optimize collaboration, KT initiatives should include joint sessions that facilitate OT–teacher exchanges and relationship-building within school contexts.

Key Messages

Contextual facilitators and barriers to collaboration between OTs and teachers include knowledge of the scope of school-OT mandate and practice, interpersonal relationship challenges, and the organization of service delivery.

Relationships matter: establishing connections within the school community supports and promotes the involvement of OT in teams by cultivating a collaborative dynamic.

Skillsets such as relationship-building, communication skills, and sharing responsibilities may warrant further research exploration in OT–teacher collaborative practices.

ORCID iDs Lina Ianni https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7935-7533

ORCID iDs Chantal Camden https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5503-3403

ORCID iDs Wenonah Campbell https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1579-0271

ORCID iDs Dana Anaby https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2453-5643

References

- Anaby D. R., Campbell W. N., Missiuna C., Shaw S. R., Bennett S., Khan S., & GOLDs. (2019). Recommended practices to organize and deliver school-based services for children with disabilities: A scoping review. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12621

- Atkins L., Francis J., Islam R., O’Connor D., Patey A., Ivers N., Grimshaw J. M. (2017). A guide to using the Theoretical Domains Framework of behaviour change to investigate implementation problems. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0605-9

- Beaudoin A. J., Héguy L., Borwick K., Tassé C., Brunet J., Leblanc É. G., Dore J., Jasmin E. (2019). Perceptions de l’ergothérapie par les enseignants du préscolaire: Étude descriptive mixte. Revue Francophone De Recherche En Ergothérapie, 5(2), 47–64. https://doi.org/10.13096/rfre.v5n2.130

- Benson J. D., Szucs K. A., Mejasic J. (2016). Teachers’ perceptions of the role of occupational therapist in schools. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 9(3), 290–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2016.1183158

- Bonnard M., Hui C., Manganaro M., Anaby D. (2024). Toward participation-focused school-based occupational therapy: Current profile and possible directions. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 17(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2022.2156427

- Boyer M.-C. (2015). Examining Individualized Support Practices in Secondary Schools. Ministère de l’Éducation, du Loisir et du Sport (MELS). https://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/education/adaptation-scolaire-services-comp/Voie8_PAI_Enseignants_en.pdf

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Bronstein L. R. (2003). A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Social Work, 48(3), 297–306. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/48.3.297

- Cahill S. M., McGuire B., Krumdick N. D., Lee M. M. (2014). National survey of occupational therapy practitioners’ involvement in response to intervention. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 68(6), e234–. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2014.010116

- Camden C., Campbell W., Missiuna C., Berbari J., Héguy L., Gauvin C., Team G. R. (2021). Implementing partnering for change in Québec: Occupational therapy activities and Stakeholders’ perceptions. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 88(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417421994368

- Campbell W. N., Missiuna C. A., Rivard L. M., Pollock N. A. (2012). “Support for everyone”: Experiences of occupational therapists delivering a new model of school-based service. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(1), 51–59. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2012.79.1.7

- Cantin N. (2021). L’Ergothérapie en milieu scolaire. Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Casillas D. (2010). Teachers’ perceptions of school-based occupational therapy consultation: Part II. Early Intervention & School Special Interest Section Quarterly, 17(2), 1–4.

- Clark G. F., Laverdure P., Polichino J., Kannenberg K. (2017). Guidelines for occupational therapy services in early intervention and schools. AJOT: American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 71(S2), 7112410010p1+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A536533150/HRCA?u=anon∼1a1deefd&sid=googleScholar&xid=69eb4863

- Clough C. (2019). School-based occupational therapists’ service delivery decision-making: Perspectives on identity and roles. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 12(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2018.1512436

- Creswell J. W., Klassen A. C., Plano Clark V. L., Smith K. C. (2011). Best practices for mixed methods research in the health sciences. Bethesda (Maryland): National Institutes of Health, 2013, 541–545. https://www.csun.edu/sites/default/files/best_prac_mixed_methods.pdf

- Ducharme D., Magloire J. (2018). A systematic study into the rights of students with special needs and organization of educations services with the Quebec school system: Summary Document. Commission des droits de la personne et des droits de la jeunesse. https://www.cdpdj.qc.ca/storage/app/media/publications/etude_inclusion_EHDAA_synthese_EN.pdf

- Freeman T. (2006). ‘Best practice’in focus group research: Making sense of different views. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(5), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04043.x

- Grandisson M., Rajotte É, Godin J., Chrétien-Vincent M., Milot É, Desmarais C. (2020). Autism spectrum disorder: How can occupational therapists support schools? Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 87(1), 30–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0008417419838904

- Green J., Thorogood N. (2018). Qualitative methods for health research. Sage Publications.

- Griffiths A.-J., Alsip J., Hart S. R., Round R. L., Brady J. (2021). Together we can do so much: A systematic review and conceptual framework of collaboration in schools. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 36(1), 59–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573520915368

- Hanft B., Shepherd J. (2016). Collaborating for student success (2nd ed). AOTA Press.

- Hillier S., Civetta L., Pridham L. (2010). A systematic review of collaborative models for health and education professionals working in school settings and implications for training. Education for Health, 23(3), 393. https://journals.lww.com/edhe/fulltext/2010/23030/a_systematic_review_of_collaborative_models_for.6.aspxhttps://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.101475

- Ianni L., Camden C., Anaby D. (2023). How can we evaluate collaborative practices in inclusive schools? Challenges and proposed solutions. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 16(3), 346–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2022.2054486

- Jasmin E., Ariel S., Gauthier A., Caron M.-S., Pelletier L., Currer-Briggs G., Ray-Kaeser S. (2019). La pratique de l'ergothérapie en milieu scolaire au Québec. Canadian Journal of Education, 42(1), 222–250. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26756661

- Jasmin E., Ray-Kaeser S. (2021). Le contexte sociétal. In Cantin N. (Ed.), L’ergothérapie en milieu scolaire (pp. 3–21). Presses de l’Université du Québec.

- Kennedy S., Stewart H. (2011). Collaboration between occupational therapists and teachers: Definitions, implementation and efficacy. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58(3), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00934.x

- Krueger R., Casey M. (1994). Focus Groups: A Practical Guide For Applied Research, New Delphi. The International Professional Publishers. https://books.google.ca/books?hl=en&lr=&id=8wASBAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PP1&dq=Krueger,+R.,+%26+Casey,+M.+(1994).+Focus+Groups:+A+practical+guide&ots=XgbMIA9JtR&sig=_wAd7XWSpH6bWiHvC3qpoZZsoD4#v=onepage&q&f=false

- Lamash, L., & Fogel, Y. (2021). Role perception and professional identity of occupational therapists working in education systems: Perception du rôle et identité professionnelle des ergothérapeutes qui travaillent dans les systèmes scolaires. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 88(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/00084174211005898

- Laverdure P. A., Rose D. S. (2012). Providing educationally relevant occupational and physical therapy services. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics, 32(4), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2012.727731

- Lynch H., Moore A., O’Connor D., Boyle B. (2023). Evidence for implementing tiered approaches in school-based occupational therapy in elementary schools: A scoping review. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 77(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2023.050027

- Meuser S., Borgestig M., Lidström H., Hennissen P., Dolmans D., Piskur B. (2022). Experiences of Dutch and Swedish occupational therapists and teachers of their context-based collaboration in elementary education. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 17(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2022.2143465

- Ministère de l'Éducation du Québec (2020). Guide pour la mise en oeuvre de la réponse à l’intervention en milieu scolaire. Gouvernement du Québec. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1cotUOFEvWzG3h5vm9X7Z66Ry8PX2M99r/view

- Ministère de l’Éducation, de Loisir et du Sport (MELS) (2007). L’organisation des services éducatifs aux élèves à risque et aux élèves handicapés ou en difficulté d’adaptation ou d’apprentissage (EHDAA). Gouvernment du Québec. https://www.education.gouv.qc.ca/fileadmin/site_web/documents/dpse/adaptation_serv_compl/19-7065.pdf

- Missiuna C. A., Pollock N. A., Levac D. E., Campbell W. N., Whalen S. D. S., Bennett S. M., Russell D. J. (2012). Partnering for change: An innovative school-based occupational therapy service delivery model for children with developmental coordination disorder. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2012.79.1.6

- Rajotte É, Grandisson M., Hamel C., Couture M. M., Desmarais C., Gravel M., Chrétien-Vincent M. (2023). Inclusion of autistic students: Promising modalities for supporting a school team. Disability and Rehabilitation, 45(7), 1258–1268. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638288.2022.2057598

- Renaud S., Bisaillon L., Baril N., Drolet M. J. (2024). The ethical issues of school-based occupational therapy practice in Quebec-Canada. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2024.2382720

- Rens L., Joosten A. (2014). Investigating the experiences in a school-based occupational therapy program to inform community-based paediatric occupational therapy practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 61(3), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12093

- Sandelowski M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4%3C334::AID-NUR9%3E3.0.CO;2-G

- San Martín-Rodríguez L., Beaulieu M.-D., D'Amour D., Ferrada-Videla M. (2005). The determinants of successful collaboration: A review of theoretical and empirical studies. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 132–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500082677

- Seruya F. M., Garfinkel M. (2020). Caseload and workload: Current trends in school-based practice across the United States. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(5). 1–8. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2020.039818

- Sider S., Maich K., Morvan J. (2017). School principals and students with special education needs: Leading inclusive schools. Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne de L'éducation, 40(2), 1–31. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90010122/

- Suter E., Arndt J., Arthur N., Parboosingh J., Taylor E., Deutschlander S. (2009). Role understanding and effective communication as core competencies for collaborative practice. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 23(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820802338579

- Tétreault S., Beaupré P., Carrière M., Freeman A., Gascon H. (2010). Évaluation de l’implantation et des effets de l’Entente de complémentarité des services entre le réseau de la santé et des services sociaux et le réseau de l’éducation: Pour un Québec attentif aux élèves handicapés ou en difficulté d’adaptation ou d’apprentissage. Centre interdisciplinaire de recherche en réadaptation et intégration sociale. https://rfdi.org/index.php/1/article/view/170

- Truong V., Hodgetts S. (2017). An exploration of teacher perceptions toward occupational therapy and occupational therapy practices: A scoping review. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 10(2), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2017.1304840

- VanderKaay S., Dix L., Rivard L., Missiuna C., Ng S., Pollock N., Campbell W. (2021). Tiered approaches to rehabilitation services in education settings: Towards developing an explanatory programme theory. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 70(4), 540–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2021.1895975

- Villeneuve M. A., Shulha L. M. (2012). Learning together for effective collaboration in school-based occupational therapy practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(5), 293–302. https://doi.org/10.2182/CJOT.2012.79.5.5

- Wintle J., Krupa T., Cramm H., DeLuca C. (2017). A scoping review of the tensions in OT–teacher collaborations. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 10(4), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2017.1359134

- Wintle J., Krupa T., DeLuca C., Cramm H. (2022). Toward a conceptual framework for occupational therapist-teacher collaborations. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 15(2), 148–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2021.1934238

Appendix A Focus Group Questions

The Theoretical Domains Framework was selected as a guiding framework due to its comprehensiveness and theory-informed approach to identifying determinants of behavior (). Examples of questions include: environmental context and resources, professional role/identity, knowledge, and interpersonal skills The focus group discussion questions also reflected the determinants for successful collaboration as described by .

QUESTION 1: In your current situations, can you describe what collaboration (with professionals or OTs) actually looks like (in your own terms)? (Can you share your experiences regarding collaborative practices in your own work settings?)

QUESTION 2: In an ideal situation, what would optimal collaboration look like? Reflect on past instances where you felt that collaboration worked very well. Describe what were the elements that helped contribute to this.

QUESTION 3: What are some resources at the organizational (school environment) level that can favor collaboration in your work settings? Discuss the procedures or policies that should be changed, added, or even removed to promote optimal collaboration.

QUESTION 4: Think about moments where you had to collaborate with professionals/teachers. Can you discuss the interpersonal skills that favor collaboration?

QUESTION 5: Concerning interpersonal skills, what would you want to learn about, or change, in order to collaborate more effectively?

QUESTION 6: Reflecting on the elements of collaboration presented, on a scale of 1 to 10, 1 being that you do not collaborate at all and 10 being you are an excellent collaborator, where would you rate yourself right now?

QUESTION 7: Considering the factors to optimize collaboration that were mentioned earlier, what kind of information (content) will be important for you to have?

QUESTION 8: Which skills will be important for you to improve or acquire to optimize collaboration?

QUESTION 9: Considering the factors to optimize collaboration that were mentioned earlier expand on some strategies that you think will help you [to learn or change practice behaviors.]

QUESTION 10: Looking at this list of strategies and mechanisms [that the participants created], which one (or ones) do you think can be most impactful in learning about collaboration and promoting changes in your practice? Is there a combination that you think would work best?

Appendix B Corresponding references for presentation content (refer to Table 1)

- Anaby D. R., Campbell W. N., Missiuna C., Shaw S. R., Bennett S., Khan S., Tremblay S., Kalubi-Lukusa J. C., Camden C, & GOLDs. (2018). Recommended practices to organize and deliver school-based services for children with disabilities: A scoping review. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12621

- Bolton T., Plattner L. (2020). Occupational therapy role in school-based practice: Perspectives from teachers and OTs. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 13(2), 136–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2019.1636749

- Bronstein L. R. (2003). A model for interdisciplinary collaboration. Social Work, 48(3), 297–306. https://academic.oup.com/sw/article-abstract/48/3/297/1941702?redirectedFrom=fulltexthttps://doi.org/10.1093/sw/48.3.297

- Clough C. (2019). School-based occupational therapists’ service delivery decision-making: Perspectives on identity and roles. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 12(1), 51–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2018.1512436

- Cook L., Friend M. (2010). The state of the art of collaboration on behalf of students with disabilities. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 20(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474410903535398

- CTREQ (2018). La collaboration entre ensignants et intervenants en milieu scolaire. Ministère de l’Éducation et de l’Enseignment supérieur (MEES). https://www.ctreq.qc.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/CTREQ-Projet-Savoir-Collaboration.pdf

- Garfinkel M., Seruya F. M. (2018). Therapists’ perceptions of the 3:1 service delivery model: A workload approach to school-based practice. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 11(3), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2018.1455551

- Hanft B., Shepherd J. (2016). Collaborating for student success (2nd ed.). AOTA Press.

- Hillier S., Civetta L., Pridham L. (2010). A systematic review of collaborative models for health and education professionals working in school settings and implications for training [review article]. Education for Health, 23(3), 393. http://www.educationforhealth.net/article.asp?issn=1357-6283;year=2010;volume=23;issue=3;spage=393;epage=393;aulast=Hillierhttps://doi.org/10.4103/1357-6283.101475

- Idol L., Paolucci-Whitcomb P., Nevin A. (1995). The collaborative consultation model. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 6(4), 329–346. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532768xjepc0604_3

- Laverdure P. A., Rose D. S. (2012). Providing educationally relevant occupational and physical therapy services. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics, 32(4), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.3109/01942638.2012.727731

- Missiuna C. A., Pollock N. A., Levac D. E., Campbell W. N., Whalen S. D. S., Bennett S. M., Hecimovich C. A., Gaines B. R., Cairney J., Russell D. J. (2012). Partnering for change: An innovative school-based occupational therapy service delivery model for children with developmental coordination disorder. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(1), 41–50. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.2182/cjot.2012.79.1.6https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2012.79.1.6

- Missiuna C., Pollock N., Campbell W., Dix L., Whalen S., Steward D. (2015). Partnering for change: Embedding universal design for learning into school-based occupational therapy. Occupational Therapy Now, 17(3), 13–15. https://caot.in1touch.org/document/4986/universaldesigned.pdf

- Ritzman M. J., Sanger D., Coufal K. L. (2006). A case study of a collaborative speech–language pathologist. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 27(4), 221–251. https://proxy.library.mcgill.ca/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=rzh&AN=106147359&site=ehost-livehttps://doi.org/10.1177/15257401060270040501

- San Martín-Rodríguez L., Beaulieu M.-D., D'Amour D., Ferrada-Videla M. (2005). The determinants of successful collaboration: A review of theoretical and empirical studies. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 19(sup1), 132–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/13561820500082677

- Smith G. W. (2009). If teams are so good..: Science teachers’ conceptions of teams and teamwork. University of Technology.

- Vaughn S., Fuchs L. S. (2003). Redefining learning disabilities as inadequate response to instruction: The promise and potential problems. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 18(3), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-5826.00070

- Villeneuve M. A., Shulha L. M. (2012). Learning together for effective collaboration in school-based occupational therapy practice. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(5), 293–302. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.2182/CJOT.2012.79.5.5https://doi.org/10.2182/CJOT.2012.79.5.5

- Wintle J., Krupa T., Cramm H., DeLuca C. (2017). A scoping review of the tensions in OT–teacher collaborations. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 10(4), 327–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2017.1359134