Introduction

The main question at the heart of this article is how lecture theaters in higher education institutions operate. To answer this question, the article draws upon two Foucauldian concepts for spatial analysis, heterotopia and the will to know. It is argued that the spatial organization of lecture theaters (e.g. linear axis, large interior, dominating location of the lecturer, seating furniture, and lack of flexibility) facilitates the formation of particular subjectivities, mainly the lecturer and the student.

The relationship between lecturer and student, this article demonstrates, can no longer be described solely through the panoptic organization of lecture halls, where one guard controls the inmates as projected in a panopticon model. The relationship between lecturer and student is beyond master and slave. They are both situated within the discourse of the university, dominated by a sovereign knowledge that promises employability and commodifies higher education. To grasp the relationships that are constituted within this space, the concept of heterotopia allows us to observe the more hopeful aspects of such environments. At the wider scale of pedagogical approaches, universities may maintain a distance from market economies, to operate as counter-sites to social norms. At an architectural scale, that is, in lecture halls, multiple worlds can be juxtaposed to enhance students’ attention.

The transformative role of universities is intertwined with the ways through which such teaching/learning environments are used. Thus, this article draws upon the current debates in educational studies to highlight the paradoxical relationship between the “real world” and “academia.” In direct response to the demands of the market, higher education aims to equip students with practical knowledge that promises a well-paid job after graduation. On the other hand, academia as an independent institution can be a liberating space allowing non-utilitarian experiments to be undertaken by students who resist being morphed into pre-determined careers and subjectivities.

This article contributes to the literature on Foucauldian studies and higher education by suggesting that heterotopia is a more productive tool than panopticon for analyzing the spatial organization of lecture halls, and space is as influential as curricula or educational policies.

Using a non-linear structure, this article is divided into three sections—revisiting heterotopia, the spatialization of knowledge, and the spatial organization of lecture halls in order to explore the heterotopic potentials of the university. First, I discuss the Foucauldian account of heterotopia in order to understand the underlying idea of retreat in the formation of the academy and its transformation following the emphasis on employability. Following Foucault’s assertion that knowledge and subjects are constructed, the second section extends Foucault’s notion of heterotopia and highlights that although norms are suspended in these counter-sites, the excluded individuals residing in this alternative space may undergo transformative practices to become an absorbable productive workforce. The third and last section looks closely at the architecture of lecture halls and analyzes the ways through which architectural configurations facilitate the construction of subjects in search of practical knowledge.

Revisiting heterotopia

Des espaces autres, translated as Of Other Spaces or Different Spaces, was originally a radio talk presented by Foucault in late 1966 (, ). By adopting an old traveler’s character, he narrated stories of the different places he had visited. Hearing the radio talk, one of the directors of the Circle of Architectural Studies (Cercle d’études architecturales) invited Foucault to speak about “Utopia and Literature” in 1967. “Of Other Spaces” was initially released to the public domain in Berlin in 1984, shortly before Foucault’s death, and was published in France posthumously in the same year. This late publication suggests that this text remained mostly unnoticed during Foucault’s life. Following the publication of Discipline and Punish in 1975, a renewed interest in the idea of heterotopia emerged giving Foucault’s spatial analysis a new visibility (: 279).

Derived from the Greek heteros (another), and topos (place), heterotopia is a medical phrase referring to a particular tissue that develops in a place other than the usual (). The term first appeared in the preface to The Order of Things (). By referring to disparate and unusual categories described by the Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges, Foucault employs this term to point to the limits of language. Etymologically meaning “non-place,” heterotopia designates the non-place of language. That is, heterotopias disrupt the grammar by which language operates. The order by which words are linked together are shattered, that is why Borges’ categorization of animals appears to be disorderly and inappropriate—“belonging to the Emperor” or “having just broken the water pitcher” do not make sense to us as proper arrangements. For Foucault, heterotopia is this disturbing space that undermines language. Later in Des espaces autres, Foucault uses this term not for discourse analysis but rather for spatial analysis, making it appealing to architects (: 281). In contrast with utopia which is unreal, he uses heterotopia to define the principles of real counter-sites by referring to a disparate and large number of examples, such as schools, military service, the honeymoon, old people’s homes, prisons, psychiatric institutions, theaters and cinemas, cemeteries, libraries, museums, carnivals, holiday camps, brothels, hammams, saunas, motels, colonies, and ships.

Foucault defines heterotopia in relation to utopia by identifying their similarities and differences. As counter-sites, heterotopias suspend, neutralize, or invert the norms. In order to systematically describe heterotopia, Foucault lists six principles that it encompasses: all cultures produce a certain form of it; its function can transform; it is capable of juxtaposing in a single real place several incompatible spaces; it is linked to slices in time whereby people arrive at an absolute break with traditional time; it presupposes a system of opening and closing that regulates its entry; and finally, it functions in relation to all remaining spaces and creates an illusionary or a perfect space.

The ongoing body of literature informed by Foucault’s concept of heterotopia can be categorized in three distinct approaches: studying a specific case following Foucault’s examples and asserting it to be a heterotopia (; ; ), adding to Foucault’s list and seeking to prove a particular spatial example to be a heterotopia (; ); and finally, describing what heterotopic spaces can do, rather than what they are, while reinterpreting this Foucauldian concept and deploying it to rethink a contemporary situation (; ; ). This article follows the last approach, that is, to analyze the spatial configurations of a number of lecture halls in educational environments and investigate their heterotopic potentials rather than presenting them as absolute heterotopia. I opt for this route to analyze what space can do. For example, in the Design Theater with bare tiered seats at the University of Auckland (Figure 6), which will be discussed later in the article, students are provided with “alternative” ways of occupying and using this auditorium. Appearing as alternative is in fact, one of the principles of heterotopia.

It is in contrast with utopias that Foucault describes the first principle of heterotopias in an implicit way: they are real counter-sites located outside of all places; they exist in all civilizations and there are two types—crisis and deviation. Crisis heterotopias offer a place or a nowhere for the occurrence of an activity that is considered to be abnormal, for example, reserved spaces for menstruating women in primitive societies, boarding schools for young men expressing their sexual virility, or honeymoons for young women who are to be deflowered. Heterotopias of crisis are without defined geographical boundaries and they provide a place that is not home. Foucault argues that in contemporary society, heterotopias of crisis are replaced with heterotopias of deviation such as rest homes, prisons, and psychiatric hospitals. Here reside two points of merit for further explanation: in a heterotopia, certain norms are suspended, that is why it is a counter-site or an alternative space. However, for how long and to what ends those norms are interrupted remain open questions that Foucault does not discuss in “Of Other Spaces.” I argue that the otherness of this alternative space is ephemeral. This difference cannot last long. Sooner or later, it will be deployed as a transformative phase to perpetuate the operation of the very system that the heterotopia disrupted. Foucault in his later works expanded on this point, suggesting that the institutionalization of the abnormal is to construct the norm.

The university, as a transformative space, operates in a similar way. Once a person is enrolled as a student, she enters a transitional environment, where she is intended to be transformed from a high school teenager (considering the majority of students are young) to an employable adult. This phase between high school and workspace is sheltered in universities. Various techniques disconnect students from the mainstream reality of work-life such as concessions, student accommodations, part-time/low-paid jobs, scholarships, student-loans, debts, and even sugar daddies or mommas (). In an interview, explicitly compares the university with heterotopia when asked about the similarity between students in higher education systems and confinement institutions he had analyzed, such as hospitals and asylums:

[T]he university is no doubt little different from those systems in so-called primitive societies in which the young men are kept outside the village during their adolescence, undergoing rituals of initiation which separate them and sever all contact between them and real, active society. At the end of the specified time, they can be entirely recuperated or reabsorbed. (p. 69)

Universities, he suggests, hold a dual function—that of exclusion and integration. First, students are put outside of society and disengaged from real life while being given some academic knowledge:

This exclusion is underscored by the organization around the student, of social mechanisms which are fictitious, artificial and quasi-theatrical (hierarchic relationships, academic exercises, the “court” of examination, evaluation). Finally, the student is given a game-like way of life; he is offered a kind of distraction, amusement, freedom which, again, has nothing to do with real life; it is this kind of artificial, theatrical society, a society of cardboard, that is being built around him; and thanks to this, young people from 18 to 25 are thus as it were, neutralized by and for society, rendered safe, ineffective, socially and politically castrated. (: 69)

Once students have gone through such a ritual of exclusion and spent a few years in this artificial world, they embody the social norms, accepted political behaviors, and desirable types of ambition. Foucault continues to argue that an absorbable workforce is produced and society can consume them. He admits that such an observation is a rough outline considering the evolution of universities (a shift from the elite toward the lower middle classes) and the specificities of geohistorical realities. What remains relevant is that universities cut off students from their real milieu in order to turn them into specific subjects, scientists, or technicians, because the development of the higher bourgeoisie depends on technological and scientific innovations. For the Nietzschean Foucault, a “subject” is created by a system in order to maximize the operation of that very system (). Here Foucault criticizes the ineffective and irrelevant knowledge taught at universities and is critical of the ways in which students are trained to be obedient and passive members of society. Such a critique is more aligned with his exploration of the apparatus of production. The prison, hospital, school, factory, and family, for Foucault, were figures of political technology, and diagrams of a mechanism of power reduced to its ideal and most effective forms (: 205).

In Foucault’s discussion on heterotopia, however, I argue, a more hopeful aspect is retained, that is, the possibility of problematizing the norm. Reading Foucault’s 1970’s notion of heterotopia alongside his 1980’s projects of exclusions uncovers a contradiction: how can a heterotopia remain outside of the wider meta-structures in which it is already embedded? In relation to the case of this article, the question would be—how can universities remain outside of capitalism when they are already embedded within it? This paradox can be addressed by suggesting that heterotopia as a counter-space can only operate within language () or, I argue, heterotopia can exist in the physical world, but its life is ephemeral, similar to the short life of fireworks. While this article mainly focuses on the fact that contemporary universities (transformed by global neoliberalism) mainly operate to create subjects who seek practical knowledge in search of better employment, the aim is also to highlight the less visible but heterotopic potentials. What can help to better understand this potential is the notion of retreat inherent in the formation of the Greek academy (; ).

As heterotopic sites, these academies were real places inextricably linked to cities, while situated outside the economic or political realms. With this complex relationship to the polis, the academies held the potential to offer a spatio-temporal experience that did not involve labor, work, or action. It should be emphasized that this article does not call for a return to the origin of the academy nor is it argued that the modern university is the continuation of the Greek academy. The life of these knowledge-producing institutions has evolved and reformed following their alliance with the government, industry, and the market. This article suggests that modern universities hold heterotopic potentials, to some extent similar to their predecessors, however remotely connected, that is, they operate with a spatio-temporal distance from the norms of society. As such, heterotopia is a better concept for analyzing these spaces than panopticon. For example, the closure of the Bauhaus and its relocation from Dessau was reinforced by the anti-bourgeois students’ attitude and lifestyle that the conservative right-wing city of Weimar found to be problematic, such as ultra-modern hairstyles, shabby clothing, and sunbathing naked (: 84).

In tracing the origin of the academy to the 4th century BC and the vision of Plato (as the founder of higher education), German cultural theorist : 33) endorses the underlying idea of retreat in the academy’s formation, where one is able to shut out the world and engage with ideas and theorems. By borrowing Foucault’s notion of heterotopia, writes that “the settlement of the Academy in the city was an issue of a ‘heterotopia’. This term defines an excluded place that fits into the normal or ‘orthotopic’ surroundings of the polis, yet totally obeys its own laws that the city finds incomprehensible, even outlandish” (p. 33). It should be noted here that Sloterdijk is specifically referring to the Greek academy which should be distinguished from contemporary universities. That the Greek academy qualifies well as a heterotopia is also highlighted by . They define heterotopia as an alternative space that is neither political nor economic, neither oikos (private sphere, hence economy) nor agora (public sphere, the place of politics), and a space in which people neither work nor act, and they suggest that, absent from Foucault’s list, it is a safe haven for Aristotle’s bios theoreticos (). It is a refuge in which one can act differently. Heterotopia contains the abnormal that is excluded from the polis and its status cannot be adequately described in economic or political terms.

Such heterotopic potentials are under attack by employability movements that seek to produce a highly trained workforce (graduates) with the necessary skills to suit the needs of the labor market and consequently guarantee graduates’ financial success in the workplace (). Although this business model, promoted by the new instrument of social control called marketing (), includes some valid points—who does not like to have a secure job after graduation?—enhancing the marketability of students has a direct and significant consequence for teaching and learning approaches. For example, in an architecture school, such dissociation from the norms of society allows students to test and create unbuildable projects that are not designed to satisfy the client or the consumer. Vocalization of architecture reinforces the “problem-based learning” approaches in architectural pedagogy through which architecture is reduced to a problem to be solved rather than a site of socio-political contestation (: 107). Thus, this article suggests that for an architecture school to act as a heterotopia of deviation, one might start to intensify rather than blur the boundary between a school of architecture and architectural practice.

The university has prevailed in modern times mainly because of its “institutional adaptability” (: 11). A key point is that parallel to discussions around the transformation of universities, an argument has remained persistent, that is, the intense and paradoxical relationship between the “real world” and “academia” and the consequential question of what the function of the university should be. Higher education institutions include two contradictory aspects that pull them in different directions: providing greater access to education for the majority of society (to increase social mobility and more attractive employment) while supporting sophisticated and expensive research necessary for the production of global knowledge (). With budget cuts and the pressure on publishing, academia in most Anglo-American countries is moving toward becoming “research institutions” in which teaching is becoming its secondary role rather than the other way around (). Competing for external funds may be one of the most obvious reasons why these institutions tend to prioritize serving industry rather than investing in teaching. Increasing the number of enrolments is another mechanism to incorporate the university into the new (global, neo-liberal, or market) economy, that is problematized under massification and vocationalization of higher education in the literature.

Massification in educational studies is a term coined to describe the growing number of global enrolments in tertiary qualifications (). There is a growing body of literature that discusses the implications of the rapid expansion of higher education for universities affected by internationalization, globalization, and marketization, including anarchy in the production of graduates whose degrees do not serve themselves nor society (), degeneration of universities into teaching factories () and the construction of students as sovereign consumers rather than as agents of change (). As observed by , the consumer culture renders higher education as a must-have commodity that is necessary to obtain better future employment. Vocationalization of education thus refers to the commodification of learning which aims to fully position individuals to best operate in the market. Undoubtedly, the autonomy and freedom of academia is a complex subject (with numerous variables across various countries with different economies) and should remain an open question.

By revisiting heterotopic sites, it becomes apparent that such sites construct a particular subjectivity—excluding abnormal or unproductive sectors from society in order to later integrate them into society. University, this article argues, operates in a similar way. It provides a transitional space in which high school teenagers are excluded from the real life of society because they are located within the theatrical environment of academia in which they gradually absorb the skills and values of the society into which they will soon be absorbed. However, there is another aspect to heterotopia, which is less explored—problematization of the habitual. That is, when a series of atypical experiences are allowed to occur in a heterotopic site, one can question why such practices are absent from the everyday life of the city. For example, being idle, unproductive, or insane is located and accepted in a retirement village or a psychiatric hospital outside a city. As counter sites, heterotopias contest the normal social orders and simultaneously become sites of resistance, given that they resist the dominant hegemonic power. Regulated colonies provide a well-organized and meticulously planned life in contrast to our real chaotic lives or the illusion of perfect sex in a brothel is far from a utilitarian domestic life. These heterotopic experiences that are different from the norm highlight the underlying exclusive system that confines certain forms of practices. In this sense, if we return to the case of this article, it can be argued that although universities are predominantly oriented toward producing a normal/docile workforce, they maintain the potential of creating the yet-to-come assemblages that can reshuffle “the system of overcoding that dominates us” (: 265). While this argument is more evident in relation to the role of pedagogical approaches in affecting and creating different generations of learners to become agents of change, I will also explore how architecture, too, can provide contested sites to unsettle the norm. To do that I will focus on a particular learning space in universities: the lecture theater. A number of lecture halls will be examined to demonstrate how architectural design can reinforce or suspend rigid spatial relations.

Spatialization of knowledge

Although heterotopias are mostly “understood as sites of resistance,” shifts such an interpretation by suggesting that heterotopias produce “new ways of knowing” because they constantly clash with the dominant orders (p. 54). For Foucault “knowledge does not exist except as a product of combat” (: 64). Topinka suggests that heterotopias problematize the laws that govern our knowledge: they destabilize the underlying structural support by which we make sense of the world; they call existing orders into question; they contest given classifications; and by doing so, they produce an intense battleground in which the creation of an alternative view (but still intertwined with the existing power relations) becomes possible. According to Foucault, knowledge as a perspective is produced based on specific orders. What heterotopias do is to make such orders visible and thus shatter them as grounds on which knowledge is produced. They can leave us with the destruction of knowledge or posing Nietzschean questions such as, “who is speaking?” and “why would we not prefer ignorance and uncertainty?” (: 264). In a time when higher education is rendered necessary for our empty cup to be filled with practical knowledge, a Foucauldian perspective ponders why we should prefer our cups to be filled rather than remain empty, or a Deleuzian reflection invites us to identify whose end we serve by pursuing continuous education (). These two questions cast doubt on the value of pursuing continuous education; on the one hand, we should ask why we need this practical knowledge, and, on the other hand, we have to ask who is benefiting from this never-ending institutional learning.

Looking at Greek philosophy in the late 1960s, identified a will to know (savoir) that cannot be reduced or assimilated to knowledge (connaissance), writing that “this desire has no kinship with knowledge.”: 27) calls the outside of knowing the “untenable vacancy (non-lieu) of knowledge and truth.” Given that he uses this spatial language to articulate “where” he should put the roots of knowledge, he regards “outside” and “non-place” to be the two key words supporting his claim that the desire to know cannot be reduced to knowledge itself. By breaking this affiliation, : 203–206) places the roots of the will to know outside of knowledge, in the “will to power.” The will to know is linked to mastery over things—we want to know in order to dominate. Knowledge, he argues, is a perspective that has been invented and has nothing to do with humanity’s instinct nor is it a divine spectacle. Knowledge is a violent act that erases differences, it is perspectivist and it distorts reality. Knowledge is a product of a battle (. Knowledge is a historical process and invention through which the subject has been constructed as an object to be known (). The emergence and construction of this modern subject is intertwined with architectural and social form that is exercised on individual bodies through disciplinary mechanisms (). The dominant spatial dimension of Foucault’s studies (asylum, clinic, and prison) demonstrates how an architectural configuration facilitates the production of a subject: an asylum as a space for the mad, a prison that creates delinquents, a clinic that produces the abnormal, and a town that creates docile citizens. Universities can be added to this list, as they construct students and a skilled workforce.

This article explores how contemporary lecture halls, originating from the early modern anatomy halls, offer a spatial context for exploring the spatialization of knowledge and the construction of selves as subjects who desire to know. The architecture of such spaces regulates the politics of teaching and directly impacts the way we communicate. For example, while discussing the political dimension of design, : 69–71) refers to the architecture of auditoriums as encompassing their form, size, spatial arrangement, acoustics, eye contact, spatial distance between the audience and speaker, and the speaker’s authority and argues that they create different types of connections, activities, and social relations. Similarly, this article suggests that the spatial organization of lecture halls—as places in which knowledge is rendered visible and articulable—facilitates the construction of certain subjectivities such as a lecturer and a student.

My starting point for writing this article is to rethink the lecture theaters in which I have been teaching a survey course. These spaces are completely separated from the outside, with sound-proof walls, double-door entrances, blocked walls without windows, and controllable artificial light—techniques to create a dark space during the day and a silent space in the middle of a chaotic campus. Mostly in semi-circular or rectangular form, they contain the maximum possible number of fixed chairs with fixed or retractable tables on tiered rows. Students are often expected to remain silent and immobile during the lectures, to take notes and to listen to one single speaking mouth (Figure 1). They look at the PowerPoint slides projected on a flat white vertical screen. The slides pass, one after another, representing the totality of the world. With high-quality immersive photographs and videos, accompanied by a list of facts, a miniaturized world is created. This is another heterotopic potential of lecture theaters—: 25) third principle of heterotopia by which it “is capable of juxtaposing in a single real space several spaces, several sites that are in themselves incompatible,” referring to concrete examples such as the theater, cinema, oriental garden and carpet, and modern zoological gardens. Composed of incompatible sites, heterotopia also acts as a “microcosm” of the world (: 26). As if by being there, we have access to the whole world. In a cinema, we are thrown into a three-dimensional space projected on a two-dimensional flat screen. In a Persian garden, we walk through a rectangular space with a strong axial organization that appears to be a microcosm of the four corners of the world. In this sense, the noise-free, window-less lecture halls provide a setting in which not only several spaces can co-exist, but more importantly, students can be thrown into another world. In our media-saturated world, creating a space in which students can feel detached from their individual virtual world is becoming more and more difficult for educators. We are confronted with a generational shift, a generation whose attention span has shifted from focused attention to hyperattention (). With a weak tolerance for boredom, hyper-attention, which is in a constant flux through multiple sources of information, poses serious challenges at every level of education (: 187). In response to this shift, the heterotopic sites of lecture halls can provide a microcosm of the world in which students can sustain and develop deep attention across a long span of time.

Figure 1

University fixed seating. In a lecture hall at the University of Auckland, students facing a speaker are invited to take notes, that is, to transcribe what they hear and see into words. An engraving on the slim timber board “Fuck tests, actually fuck uni” illustrates how this horizontal flat continuous platform is used for marking of thoughts and expression of frustrations. These marks were removed and cleaned later. Photo by the author (2016).

In addition to this positive heterotopic potential, an authoritarian feature of lecture halls should be highlighted. Nonflexible, insulated lecture theaters with a strong linear axial orientation enforce a one-way communication platform and promise a smooth transmission of knowledge from one truth-speaking mouth to many listening ears through writing hands. The dominant axis directed toward the front of the room creates a hierarchy between the lecturer and the students: the one who is expected to speak is placed at the center of attention and the crowd who is expected to listen is placed in the background. What is projected to the students is not only information, but also an image of themselves as well-paid, white-collar worker in the future. This feature is less about the organization of objects in space and more about the creation of a microcosm of multiple geographical locations across time in which not only the unknown can be revealed, but also certain promises can be sold, such as employability. The most obvious architectural analysis of lecture theaters focuses on the spatial arrangement, which considers the teacher as the master and students as slaves. As I have alluded to before, such a panoptic model of exploration is no longer valid. Instead it is sovereign knowledge that should be taken into account and how it uses space to create subjects who pursue it endlessly. This point is well demonstrated by analysis of seminar rooms in research universities. Based on the psychoanalysis works of Jacques Lacan, he argues that both students and teachers constitute the discourse and the dialectic of the university. Their connection is no longer one of master and slave; it is replaced by sovereign knowledge and its products. A product of such sovereign knowledge can be the promise of employability.

Lecture theaters as an architectural typology are rigid structures because they have to serve a very utilitarian function; consequently, we see very few projects with alternative design that extends the heterotopic potential of these spaces. I refer here to two contemporary precedents.

In the first scenario, Charles Correa’s Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown (Lisbon, Portugal, 2010), a sculptural complex for biomedical research, consists of three curvaceous white main buildings around a limestone paved plaza. There is also a public amphitheater in one of these blocks that accommodates scientific meetings and performances. One side of this lecture theater is a large elliptic window, opening the internal space toward the Tagus River (Figure 2). The interior linear axis is no longer solely oriented toward the speaker standing in front of the white screen, but also pointed toward the outside. The audience is no longer facing a singular point of view, but rather another point of “view” that extends thoughts outside the closed walls of the auditorium. Perhaps this is where the “lawless law of the world” shimmers, “an exterior to our interiority,” as Foucault describes a thought outside subjectivity (). Similar to any other lecture theater that allows the co-existence of incompatible spaces, in this amphitheater, we are not only invited to concentrate on the performance or the lecture in front of us, but we are also situated close to an unorthodox window on our left—framing a picturesque landscape. This window disrupts the authority of the knowledge being rendered as visible and articulable. As highlights that heterotopias are not only sites of resistance, but more importantly contested sites in which new ways of knowing can be produced, the disruption in the spatial organization of this theater is a bold move. What makes Correa’s work unique is the design of the window, not as a readymade glazed curtain wall, but rather a frame with an unusual form and size. The faraway landscape is framed within this large ovoid window and is brought in close proximity to the audience inside. Although the audience is facing the usual white screens, this large opening is perhaps a reminder of the unknown world that cannot be captured or transferred into the domain of the known (). Here, two incompatible worlds of the known and the unknown are juxtaposed.

Figure 2

Alternative lecture theaters. In Charles Correa’s Champalimaud Centre for the Unknown (Lisbon, Portugal, 2010), one side of a lecture theater is punctuated by a large oval window. The daylight and the view of the Tagus River disrupts the stability of the interior, and the solid internal linear axis is interrupted by the shift to the outside. Photo by José Campos, source: https://www.archdaily.com/140623/champalimaud-centre-for-the-unknown-charles-correa-associates?ad_medium=gallery.

The auditorium in the Champalimaud Centre can be considered as a heterotopia: the entry is regulated as a biomedical research center and its function can change from presenting scientific findings to leisure performances. Similar to a cinema, multiple incompatible worlds can co-exist and it is an illusion of a perfect space where knowledge can be transferred. The amphitheater in the Champalimaud Centre is linked to very precise slices of time governed by the duration of each talk or performance and located within a research institution centered around the cancer crisis it houses, the abnormal. By analyzing the heterotopic potential of lecture theaters, we are able to understand architecture as more than a tool for the organization of people in space. Architecture will be understood with more agency in creating a contested site for problematizing the norms we have taken for granted.

Another contemporary project in which the standard typology of lecture halls is altered is in Milstein Hall at Cornell University, designed by OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture) (New York, US, 2011), where certain rigid spatial relations are interrupted. With an industrial aesthetic, a steel box sitting on a concrete mound, OMA designed an extension to the Cornell College of Architecture, Art and Planning in Ithaca. On top of the concrete mound, there is an auditorium that extends into the underground and provides a pedagogical platform for this architecture school. This auditorium is enclosed by curtains designed by Petra Blaisse and glass walls surround this space (Figure 3). A platform similar to a corridor is situated within the auditorium overlooking the tiered seats and allows for informal engagement with the presentation. This platform extends the width of the auditorium and creates a less utilitarian space. A spacious flat area, in front of the lecture theater, provides a flexible space that can be furnished in different ways: parallel rows of chairs facing the screen or arranged in a circular way facing each other. This innovation is completely different from the common practices of design in learning environments that are limited to incorporating new materials, or cutting-edge IT (information technology) or acoustic technologies. For example, the dominance of the strong linear axis is reduced, un-programmed spaces are added to the interior, and the relation between inside and outside is increased. In both projects, it is through the careful design of basic architectural elements (a wide window or providing programmed spaces) that oppressive features of such learning environments have been identified, problematized, and elevated by architects.

Figure 3

Alternative lecture theaters. Milstein Hall at Cornell University designed by OMA (NY, US, 2011). The glass wall and the curtains can be seen in both photos as enclosing elements, thus the interior has the potential to be visually linked to the outside. Photo by Matthew Carbone, source: https://www.archdaily.com/179854/milstein-hall-at-cornell-university-oma-2.

For Foucault, the subject who seeks knowledge is a historical construction. The desire to know is not a natural call. We embody this quest. From a Foucauldian point of view, space plays a key role in the construction of modern subjects. Focusing on the university and the student as the main point of this article, this section explored how contemporary lecture halls provide a suitable spatial context for exploring the spatialization of knowledge and the construction of ourselves as subjects who desire to know. With a fairly rigid design, these halls remain places in which knowledge is rendered visible and articulable. Although a few contemporary examples demonstrate alternative models for these learning spaces, the basic design principles have remained unchanged.

Spatial organization of lecture halls

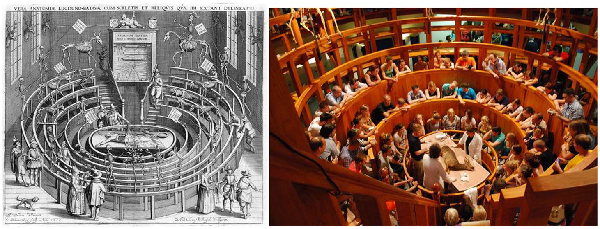

One of the few studies that have specifically analyzed lecture halls from an architectural perspective is a chapter “Invisible knowledge” by , in his book Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types. He shows how the current model of lecture theaters was appropriated—in order to promote knowledge among the public and working class—from the 16th- and 17th-century anatomy theaters and the 18th-century elite academic models. A centric form with tiered seats remains as a model for learning spaces, while internal formal hierarchies and segregatory forces were later eliminated (: 244). Tracing back to the 16th century, Markus compiles a series of examples of European lecture theaters that varied in size, form, and seating arrangements. The plan of anatomy theaters took different forms: square (Domus Anatomica in Copenhagen University, 1645), octagonal (the anatomy theater in the Royal Academy of Surgery, rue des Cordeliers, Paris, 17th century), full circle (the anatomy theater in the University of Leyden, 1593), or semi-circular (École de Chirurgie, Paris, by Gondoin, 1769). They also varied in the form of the entrance (whether to make the lecturer’s entry ceremonial or not) and in the relationship between teacher and the audience (depending on how steep the floor was). : 233) suggests that it was in the 18th century that major non-medical teaching institutions adopted the form of an amphitheater as a model for lecture spaces, with the elite being the key audience. He points out that the theaters for the upper class came to an end in England’s industrialized society of the 18th century and when science became available to the working class. Whether such a dissemination of knowledge was an alternative to art, or an education of the working class, or a means of social control, the semi-circular centralized form with tiered seats remained the architecture in and through which knowledge was made visible and articulable.

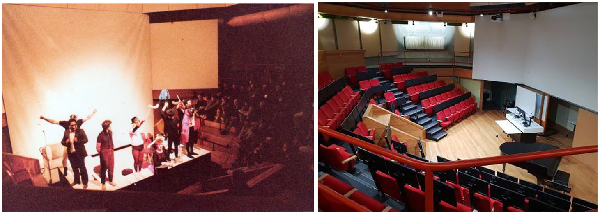

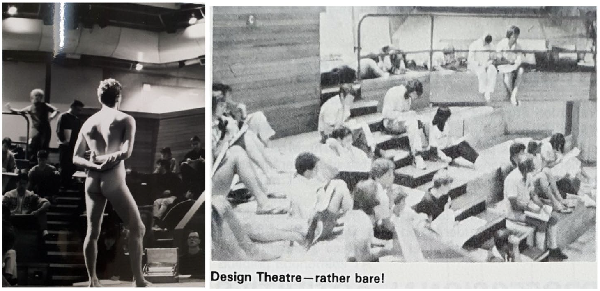

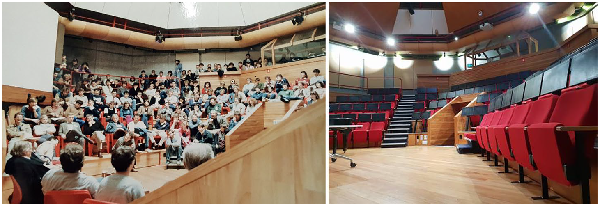

The anatomy theater in the University of Leyden (1593) is one of such spaces that has survived almost in its original form (Figure 4). It is now located inside Boerhaave Museum of the history of science and medicine in the Netherlands. Built as a new and permanent theater within the existing square room structure of a church, it was an extravagant and ornately decorated building. It was more than a practical or educational anatomy construction. Performing a dissection was a theatrical performance as illustrated in two engravings of this space (: 130). What we can recognize in the elaborate 17th-century engraving by Willem van Swanenburgh is a circular, centralized form with six concentric rows of benches: two rows of wooden narrow seats and four tiered ones for standing. The upper rows are circled by a narrow wooden handrail that is suggestive of a place for temporary observation. In contrast to some contemporary university lecture halls, there were no fixed strip tables and no individual chairs with retractable tablet arms. The audience was obviously not provided with a space to sit for a long time to take notes. Students in a modern auditorium, on the other hand, are quite often provided with an individually comfortable seat and a table in front, on which they are invited to transcribe their observations and what they hear into words. For example, one of the lecture halls in the School of Architecture and Planning at The University of Auckland, New Zealand, completed in 1978 (as a part of the construction of a new building for the School of Architecture), is currently furnished with a maximum number of fixed chairs with a table in front. In the original design of this space, however, no furniture was attached to seats and the wooden tiered seats provided a flexible space in which alternative modes of knowledge production could also occur. As shown in Figure 5 the design theater was used by architecture students for a satirical performance in the early 1980s. As shown in Figure 6, each student occupies a wider space for drawing a nude, sitting freely on long rows. Being refurbished with tight inflexible chairs, the transformation of this lecture hall, it can be argued, responds to the massification of higher education (Figure 7).

Figure 4

Anatomy theater. Left: The anatomy theater in the University of Leiden (1593) (source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anatomical_theatre#/media/File:Anatomical_theatre_Leiden.jpg). Right: Contemporary condition of the same space inside Boerhaave Museum of history of science and medicine in the Netherlands (source: https://nl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leids_Anatomisch_Theater#/media/File:MuseumnachtLeiden2010.jpg).

Figure 5

Design theater at the University of Auckland. Audience on tiered seats watch architecture students’ performance. This space was not yet furnished with immobile seats. Sources: (UoA Archive) compare with the current condition of the space on the right reducing the flexibility of space. Photo by author, 2019.

Figure 6

Design theater at the University of Auckland. Left: Life drawing of a nude. Students seating freely holding large notebooks and each occupies a space that is obviously larger than a 40-cm-wide chair. Source: (1970s, UoA Archive). Right: Image of the internal space of the auditorium used in the University’s annual pamphlets in 1983 advertising the architecture degree. Students with bare feet and sleeping on their stomach hold papers in their hands, and the flexible space is noticeable. Source: (UoA Archive).

Figure 7

Design theater at the University of Auckland. Left: In the 1980s, movable red chairs were added to this auditorium. In this photo taken during an international conference “Gone to Kiwi” in 1983, the audience are mostly situated on individual chairs with similar postures with an exception of a few standing at the back leaning on the handrail. Source: (UoA Archive). Right: Later, the space was completely refurbished with tight inflexible chairs. Photo by the author, 2019.

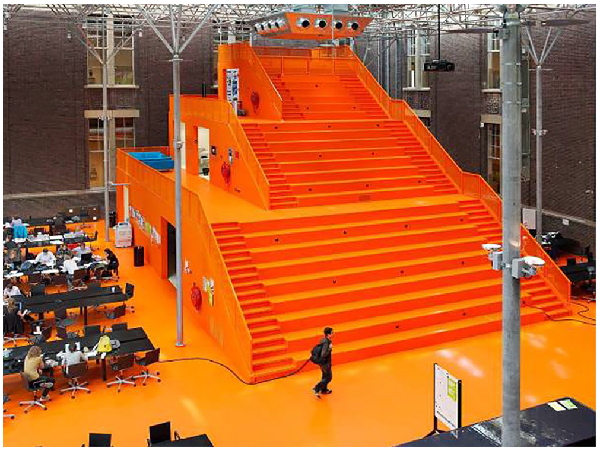

Moreover, given that lecture theaters are created to contain a large number of students, their size enforces the idea that the majority learn in a similar way. If someone is deaf, blind, or suffers from social anxiety, he or she will be instantly excluded from this space. This can be considered a pitfall of such an educational space. A contemporary alternative model is the 2009 The Why Factory, a research institute designed by MVRDV in Delft University of Technology (Figure 8). Located within the courtyard of a historical building, it contains a giant, bright orange, three-story auditorium stair. It is the main distinctive feature of this area aimed at providing a versatile and flexible space. The tiered orange seats are not enclosed inside a lecture hall but rather they are exposed. There are no strip tables and there is no singular orientation toward the blank white projection panel. Seats are long, continuous benches on which one can also lie, relax, or sleep. There is no designated space for a speaker and no lectern.

Figure 8

The Why Factory, Delft University of Technology. Bright orange three-story auditorium stair located within the courtyard of a historical building promises a flexible learning environment. Sources: https://www.mvrdv.nl/projects/64/the-why-factory-tribune.

Setting up a binary criterion to evaluate whether traditional lecture halls are good for learning or not is not the point of this article. Rather, the aim is to explore how these spaces construct a particular subjectivity using individual bodies. With a centralized point for a lecturer surrounded by students facing one direction, this particular spatial configuration is also reminiscent of a Foucauldian panopticon—not as a surveillance machine, which is the most commonly misused interpretation, but rather as power-knowledge relations exercised over bodies. The spatial configuration of lecture halls is not totally about the panoptic gaze; rather, it corresponds to : 29) interpretation, that “the abstract formula of panopticism is no longer ‘to see without being seen’ but to impose a particular conduct on a particular human multiplicity.”

In the anatomy theater of the University of Leiden, human multiplicity was oriented toward a dissected body placed on an anatomy table at the center of the room as the key object of discussion and observation (Figure 3). Today, students enter the auditorium oriented to a flat white screen and a lectern equipped with various audio-visual technologies that not only extend the body of the lecturer but also designate her as an authority, a speaking subject, the one who makes invisible knowledge articulable and visible. In the anatomy theater, the demonstration occurred on a flat horizontal surface on which a body was dissected. In contemporary lecture theaters, the tabula rasa has remained (as a lectern, flat vertical screens or just a table) and the concrete dead body has been eliminated. This absence is reminiscent of an invisible knowledge waiting to be revealed by the demonstrator to the audience situated in seats with minimum possibility of movement.

Following emphasis that “[h]eterotopias are extreme,” it can be argued that as a heterotopic site, where various forms of subversion are possible, an auditorium provides a non-place or a liminal space in which human multiplicity is transformed into students and potential future skilled employees (p. 32). A Foucauldian response would be to destroy “the subject who seeks knowledge in the endless deployment of the will to knowledge” (: 97), as one of his key philosophical contributions is that subjectivity and the will to know are constructions. However, as an educator, this approach is highly problematic, mainly because Foucault “cannot see the war that marketing, as the ‘science’ of societies of control, is waging against programming institutions” (: 122). For : 123), this is Foucault’s blind spot in the analysis of academic institutions. The creation of a subjectivity is not good or bad in and of itself. The point is that it is dangerous to stop realizing that our desires have been constructed by institutions in which we are remade for the sake of society. However, if we acknowledge the heterotopic distance from marketing demands, it can provide heterotopic possibilities for individual students in academia to open up to experiments ()—what these experiments can be and how they can be intensified by spatial configurations would be potential topics for the next project.

Concluding remarks

In this article, I have sought to deploy two Foucauldian notions developed in the 1970s in order to rethink the ways spatialization of knowledge occurs in lecture halls as heterotopic sites wherein particular subjectivities (student/lecturer) are constructed. Academia and lecture halls were two scales that helped me to investigate this idea. It was argued that the notion of heterotopia is more relevant for spatial analysis of lecture theaters than panopticon. The objective of this preliminary exploration was not to arrive at a specific answer, so to speak. Nor for that matter did I address alternative models for educational spaces. Instead, I offered an oscillation between two end points of a spectrum focusing on how lecture halls might operate. On the one hand, the university’s tendency is to equip students with practical knowledge that is useful for the market, such as seen in the refurbished design theater at The University of Auckland. On the other hand, the university can become a liberating space with heterotopic potentials that allow individuals to create a yet-to-come subjectivity, such as The Why Factory in Delft University of Technology. Lecture halls at both points of this spectrum are heterotopic sites in which knowledge is deployed as a visible object that docile bodies can consume, or as critical practice, enabling seemingly formless students to test novel ways of becoming.

I would like to thank the reviewers and the journal editor for their constructive comments and suggestions. Also thanks to Prof. Ian Buchanan for his critical questions that helped me to better pose the argument of the paper.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The open-access publication of this paper was supported by the PBRF fund granted by the School of Architecture and Planning at the University of Auckland, New Zealand.

Farzaneh Haghighi

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9697-5387

1. During the 1970s, architects found the notion of heterotopia the most inspiring spatial concept. Later, Foucault’s call for a different approach to the history of the present also affected the architectural discourse. For instance, questions the agency of an architect; highlights the politics of urban planning and heritage policies; and calls for a method of historical enquiry that can analyze the appearance and endurance of specific forms in modern architecture.

2. See: ; ; .

3. In the late 1960s, Foucault devoted a series of lectures to Nietzsche in different universities in France, the United States, and Canada. The long essay “Nietzsche, Genealogy, History” () was the outcome of those lectures published in homage to French philosopher Jean Hyppolite (his predecessor in the same chair) while Foucault was teaching at Collège. In 1970, when he was 43 years old, Foucault was elected to teach at the Collège de France with the title of his chair being “The History of Systems of Thought.” This was after the publication of Archeology of Knowledge (1969) and before Discipline and Punish (1975). Deleuze had already published Nietzsche and Philosophy in 1962. Foucault’s inaugural lecture series delivered from December 1970 is published as a book entitled Lectures on the Will to Know: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1970–1971 and Oedipal Knowledge.

4. ; https://rijksmuseumboerhaave.nl/engels/whats/

5. Called Valium of the Dolls, this performance on modern architecture was written by graduate Elizabeth Farrelly, who is currently a Sydney-based architecture, critic, and columnist writing in the liberal-minded newspaper Sydney Morning Herald in Australia.

6. I acknowledge the institutional disability services—aligned with addressing diversity—that is provided for all students.

References

- Altbach PG (2015) Massification and the global knowledge economy: the continuing contradiction. International Higher Education 80(4): 4.

- Altbach PG, Reisberg L, de Wit H (2017) Responding to Massification: Differentiation in Postsecondary Education Worldwide. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Ballantyne A (2016) Remaking the self in heterotopia. In: Soussloff CM (ed.) Foucault on the Arts and Letters: Perspectives for the 21st Century. London: Rowman & Littlefield International, 181–198.

- Beckett A, Bagguley P, Campbell T (2017) Foucault, social movements and heterotopic horizons: rupturing the order of things. Social Movement Studies 16(2): 169–181.

- Bowers T (2018) Heterotopia and actor-network theory: visualizing the normalization of remediated landscapes. Space and Culture 21(3): 233–246.

- Boyer MC (2008) The many mirrors of Foucault and their architectural reflections. In: Dehaene M, De Cauter L (eds) Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postcivil Society. Oxon: Routledge, 52–73.

- Clements P (2017) Highgate cemetery heterotopia: a creative counterpublic space. Space and Culture 20(4): 470–484.

- Davis G (2017) The Australian Idea of a University. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

- Defert D (1997) Foucault, space and the architects. In: David C, Chevrier J-F (eds) Politics, Poetics: Documenta X the Book. Ostfildern-Ruit: Cantz, 274–283.

- Defert D (2013) Course context. In: Defert D (ed.) Lectures on the Will to Know: Lectures at the Collège de France 1970-1971 and Oedipal Knowledge. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan, 262–286.

- Dehaene M, De Cauter L (2008) The space of play: towards a general theory of heterotopia. In: Dehaene M, De Cauter L (eds) Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postcivil Society. Oxon: Routledge, 87–102.

- Deleuze G (1992 [1990]) Postscript on the societies of control. October 59: 3–7.

- Deleuze G (2012 [1986]) Foucault. London: Continuum.

- Deleuze G, Guattari F (1987 [1980]) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Engel S, Halvorson D (2016) Neoliberalism, massification and teaching transformative politics and international relations. Australian Journal of Political Science 51: 546–554.

- Faubion JD (2008) Heterotopia: an ecology. In: Dehaene M, De Cauter L (eds) Heterotopia and the City: Public Space in a Postcivil Society. Oxon: Routledge, 31–39.

- Foucault M (1984 [1971]) Nietzsche, genealogy, history. In: Bouchard FD, Simon S (eds) The Foucault Reader. New York: Pantheon Books, 76–100.

- Foucault M (1986 [1984]) Of other spaces. Diacritics 16: 22–27.

- Foucault M (1979 [1975]) Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Foucault M (1990) Maurice Blanchot: the thought from outside. In: Foucault M, Blanchot M (eds) Foucault/Blanchot: Maurice Blanchot: The Thought from Outside and Michel Foucault As I Imagine Him. New York: Zone Books, 7–58.

- Foucault M (1996 [1971]) Rituals of exclusion. In: Lotringer S (ed.) Foucault Live: Interviews, 1961-84. New York: Semiotext(e), 68–73.

- Foucault M (1998 [1984]) Different spaces. In: Faubion JD (ed.) Essential Works of Foucault 1954–1984: Aesthetics, Method, and Epistemology. New York: The New Press, 175–186.

- Foucault M (2007 [1966]) The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. London: Routledge.

- Foucault M (2013 [2011]) Lectures on the Will to Know: Lectures at the Collège de France, 1970-1971 and Oedipal Knowledge. Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Friedewald B (2009) Bauhaus. Munich: Prestel.

- Gent L, Llewellyn N (1990) Renaissance Bodies: The Human Figure in English Culture c.1540-1660. London: Reaktion.

- Grinceri D (2016) Architecture as Cultural and Political Discourse: Case Studies of Conceptual Norms and Aesthetic Practices. London: Routledge.

- Hayles NK (2007) Hyper and deep attention: the generational divide in cognitive modes. Profession 1: 187–199.

- Hirst PQ (2005) Space and Power: Politics, War and Architecture. Cambridge: Polity.

- Kalfa S, Taksa L (2015) Cultural capital in business higher education: reconsidering the graduate attributes movement and the focus on employability. Studies in Higher Education 40: 580–595.

- Lax SF (1998) “Heterotopie” aus der Sicht der Biologie und Humanmedizin [‘Heterotopia’ from a biological and medical point of view]. In: Ritter R, Knaller-Vlay B (eds) Die Affäre der Heterotopie [Other Spaces: The Affair of the Heterotopia]. Graz: Haus der Architektur, 114–123.

- Lees L (1997) Ageographia, heterotopia, and Vancouver’s new public library. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 15: 321–347.

- Lou J (2007) Revitalizing Chinatown into a heterotopia: a geosemiotic analysis of shop signs in Washington, D.C.’s Chinatown. Space and Culture 10: 170–194.

- Macintyre S, Brett A, Croucher G (2017) No End of a Lesson: Australia’s Unified National System of Higher Education. Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Melbourne University Press.

- Mansfield N (2000) Subjectivity: Theories of the Self from Freud to Haraway. Sydney, NSW, Australia: Allen & Unwin.

- Markus TA (1993) Buildings and Power: Freedom and Control in the Origin of Modern Building Types. London: Routledge.

- Martin R (2015) The dialectic of the university: his master’s voice. Grey Room 60: 82–109.

- Mohammadzadeh Kive S (2012) The other space of Persian garden. Polymath: An Interdisciplinary Arts and Sciences Journal 2: 45–67.

- Molesworth M, Nixon E, Scullion R (2009) Having, being and higher education: the marketisation of the university and the transformation of the student into consumer. Teaching in Higher Education 14: 277–287.

- Nixon E, Scullion R, Hearn R (2018) Her majesty the student: marketised higher education and the narcissistic (dis)satisfactions of the student-consumer. Studies in Higher Education 43: 927–943.

- Northcott M (2017) Students turning to “sugar daddies” to scrape through university. Stuff, . Available at: https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/88389245/students-turning-to-sugar-daddies-to-scrape-through-university (accessed 10 April 2019).

- Rijksmuseum Boerhaave (n.d.) Available at: https://rijksmuseumboerhaave.nl/engels/whats/ (accessed 10 April 2019).

- Schrift AD (2018) Nietzche and Foucault’s “will to know..” In: Rosenberg A, Westfall J (eds) Foucault and Nietzche: A Critical Encounter. London: Bloomsbury, 59–78.

- Scott P (1997) The changing role of the university in the production of new knowledge. Tertiary Education and Management 3: 5–14.

- Slaughter S, Taylor BJ (2016) Higher Education, Stratification, and Workforce Development: Competitive Advantage in Europe, the US, and Canada. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Sloterdijk P (2012 [2010]) The Art of Philosophy: Wisdom as Practice. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Smith CL (2017a) Amorphous continua. In: Radman A, Sohn H (eds) Critical and Clinical Cartographies: Architecture, Robotics, Medicine, Philosophy. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 101–119.

- Smith CL (2017b) Bare Architecture: A Schizoanalysis. London: Bloomsbury.

- Stiegler B (2010 [2008]) Taking Care of Youth and the Generations. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Teyssot G (1998) Heterotopias and the history of spaces. In: Hays KM (ed.) Architecture Theory Since 1968. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 298–305.

- Topinka RJ (2010) Foucault, Borges, Heterotopia: producing knowledge in other spaces. Foucault Studies 9: 54–70.

- Van der Zwaan B (2017) Higher education in 2040. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Wesselman D (2013) The high line, “the balloon,” and heterotopia. Space and Culture 16: 16–27.

- Yaneva A (2017) Five Ways to Make Architecture Political: An Introduction to the Politics of Design Practice. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.