Introduction

Dutch policies aim to encourage older adults to ‘age in place’ (), emphasizing the family’s essential role in providing care at home for individuals with dementia. Healthcare professionals offer support to informal caregivers in this process. There are over 800,000 individuals in the Netherlands who provide some form of care to a person with dementia (). There is a growing number of caregivers from culturally diverse backgrounds; this is linked to the 3-4x higher prevalence of dementia in some diverse demographic groups in the Netherlands than in native Dutch (). This higher prevalence has in turn been associated with a higher prevalence of risk factors for dementia such as diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, and low levels of education (). In sum, rapidly growing numbers of patients with dementia are expected among diverse populations in the Netherlands, resulting in increasing numbers of informal caregivers with a migration background. These caregivers may experience particularly high levels of burden as some demographic groups tend to utilize professional care less frequently and rely more on informal dementia support (). This has important implications for the provision and organization of dementia care (for more context see: text box 1).

Text box 1. Research in context: Aging in the Netherlands and core values of the Dutch health care system

On January 1, 2024, the Netherlands had 3,677,228 residents aged 65 or older, totaling 20.5 percent of the population. This marks a significant increase in the aging population from 12.9 percent in 1990 (). Currently, an estimated 300,000 people are living with dementia in the Netherlands (; ), who are cared for by 800,000 informal caregivers (). Dutch policies encourage older adults to “age in place,” emphasizing the essential role of families in providing at-home care for individuals with dementia (). Healthcare professionals support informal caregivers in this process. Although the national care standards for dementia () place significant emphasis on cultural diversity and potentially differing needs and wishes of patients with a migration background, the underlying values of the Dutch healthcare system may not reflect the values prioritized by all patients. Medical ethics training in the Netherlands primarily emphasizes the four principles of autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence, and justice (; ), with an increasing focus, however, on patient autonomy (e.g. in the Dutch Doctors Federation’s guidelines (). Furthermore, in 2020, shared decision making was added as a prerequisite in doctor-patient encounters in Dutch law (). Autonomy and shared decision-making in patient-doctor interactions may not necessarily align with the preferences of individuals who score high on relational interdependence holding strong beliefs in social hierarchy, who may prefer involving family members in medical decision-making ().

Informal caregivers (e.g. children or partner) of culturally diverse patients with dementia experience high levels of caregiver burden, particularly with increasing dementia severity or in cases where the caregiver is the spouse (). Burden levels can be positively influenced by the possibility to mobilize help within the network of the caregiver, such as having a social network to fall back on or by using formal care services (). Gender norms within the care context also influence the caregiver’s experience and level of experienced burden (). Research suggests that in diverse families, caregiving responsibilities are often unequally distributed, with one specific family member – typically a woman – bearing the primary caregiving burden without relying on professional care services (; ). Several factors may impact the caregiving experience, such as a family’s and individual’s positions on the collectivistic-individualistic continuum. In collectivistic cultures, the family plays an essential role; important principles are showing respect for older family members and taking responsibility for one another by organizing care together (). A seminal work by highlights that many North American and European cultures prioritize an independent self-concept, viewing the self as separate, autonomous, and defined by individual traits. In contrast, people from many Asian, African, and Latin American cultures typically embrace an interdependent self-concept, seeing themselves as intrinsically connected to a larger social network, including family and others with whom they share bonds ().

Another potentially relevant cultural factor is the continuum of femininity-masculinity. Historically, caregiving has been considered as a feminine activity (). Some studies have considered caregiving through a masculine lens wherein caregiving responsibilities are often delineated in terms of more functional tasks (). Interestingly, found that hierarchical and gendered roles and expectations were increasingly being challenged and negotiated in minority ethnic families. Last, cultural perspectives may also impact caregiver experiences. Caregivers from diverse backgrounds that do not personally provide care to their loved one may experience feelings of shame, which in turn serves as a barrier to turn to professional services (). In the case of religious caregivers, particularly within the Muslim community, other members may interpret accepting help from outside the community as rejecting Allah’s (God’s) test or divine will (; ).

Caregivers of diverse individuals with dementia may encounter several barriers in their role of informal caregiver. First, they may experience difficulties in adjusting their lives and have limited knowledge or awareness of available care services (; ). Second, access to and use of dementia-related healthcare may subsequently be influenced by the ‘approachability’, which encompasses transparency and the provision of information regarding available dementia services and treatments, and ‘acceptability’, referring to the cultural and social factors that may affect the utilization of these services (). Furthermore, seeking assistance or support may be particularly challenging when a lack of trust further undermines the ‘approachability’ and ‘acceptability’ of the available dementia services (). Previous encounters with discrimination and prejudice can impact the ability to effectively navigate healthcare systems and services (). Lastly, dementia is often diagnosed at a later stage in diverse populations (), potentially impacting access to resources and services.

As is apparent from this summary of the existing literature, there has been an emphasis on factors that stand in the way of good care, while limited attention is paid to what motivates and enables (i.e. facilitates) caregivers (to continue) to provide care in the home setting. did show that factors such as love and religion can be motivators to provide care.

Given the policy emphasis that is placed on ‘aging in place’, it is vital to examine these motivators and potential facilitators to providing (often long-term) care in the home setting, as these policies are likely attained only by both overcoming barriers to care and investing in facilitating factors. The goal of this study is therefore to examine the variation in culturally diverse informal caregivers’ motivators and facilitators to providing care. The following research question was formulated: What facilitators can be identified to enhance the provision of long-term care at home by culturally diverse informal caregivers? By examining these factors, the study seeks to identify ways to lift existing barriers to care and to integrate facilitators into care practices and policies, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful aging in place with optimal quality of life.

Methods

Recruitment of participants

We enrolled informal caregivers of patients with a wide variety of dementia subtypes and a broad range of time since the diagnosis (3 weeks up to 10 years prior). The participants were mainly recruited through the Alzheimer Center of the Erasmus Medical Center and its multicultural memory clinic in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. The attending medical professional asked the caregiver during the visit whether they would consider participating in the study, with the first author following up with detailed study information and obtaining informed consent. Two caregivers were included while the patient was temporarily admitted to the inpatient ward of the department of Geriatric medicine of the Erasmus Medical Center in Rotterdam. A subset of caregivers was included using snowball sampling, i.e., included caregivers suggested possible other participants for the study. The caregivers were interviewed between January 2022 and June 2023.

In selecting participants, the study explicitly aimed to capture intersecting dimensions of diversity, particularly regarding the cultural backgrounds of both patients and caregivers. Accordingly, the inclusion criteria were broadly formulated: participants were eligible if they were informal caregivers (e.g. family or friends) of patients with a formal dementia diagnosis, including a wide range of dementia subtypes and disease stages. Additionally, caregivers were required to provide care within the home environment of the person with dementia, though they were not required to cohabitate. We excluded professional caregivers and caregivers of patients not formally diagnosed. Although not a strict criterion, our aim was to recruit a balanced sample of caregivers with and without a migration background, representative of the demographics of major cities in the Netherlands (). Additionally, all caregivers needed to be 18 years or older.

Data collection

The data for this study were collected by conducting semi-structured, in-depth interviews and analyzing the transcripts using thematic analysis in a population of dementia caregivers of both native Dutch patients and patients with migration backgrounds. To ensure rigor and trustworthiness in the research process, several strategies were employed, including member checking to validate findings with participants, and researcher triangulation to validate the data. The data were collected by the first author (NL) through interviews that were conducted face-to-face (n = 14), online via Teams (n = 4) or through telephone (n = 2). The average duration of the interviews was 45 minutes. All participants spoke Dutch during the interviews. The interviews were structured using an interview guide in Dutch (see the supplemental material for an English translation). The interview guide was developed partially based on existing literature, ensuring that key themes relevant to the experiences of the caregivers were included. This literature-informed approach helped to enhance the comprehensiveness and relevance of the questions. We inquired about for example the relationship between the caregiver and person with dementia prior to the diagnosis, but also asked questions to obtain a better understanding of the context of providing care, such as “can you describe a day in your lives?“, “why do you provide care?“, “what are you proud of in taking care of your loved one” and “what helps you cope?“. Furthermore, we collected information about the demographics of the caregiver and patient, dementia severity of the patient at the moment of the interview, and prior experiences with caregiving in general.

Data analysis

The audio recordings were transcribed verbatim and analyzed independently by two authors (NL and FF) using Atlas.ti. We acknowledge that the potential impact of the researchers’ cultural backgrounds hold significance, particularly within the context of this study where the interplay between the different cultural contexts is salient. NL is primarily socialized within the Moroccan and Dutch culture; FF is mainly socialized within the Dutch culture (as are coauthors JMP, SF, and RvB). The transcripts of the interviews were analyzed by following the open, axial, and selective coding process (). In the open coding process, the researchers assigned labels to text elements of the transcripts. During axial coding the labels in the open coding process were examined and some of them were grouped in one overarching code. The overarching codes were then discussed between the researchers. The last step was the selective coding process where associations and connections were made to identify themes.

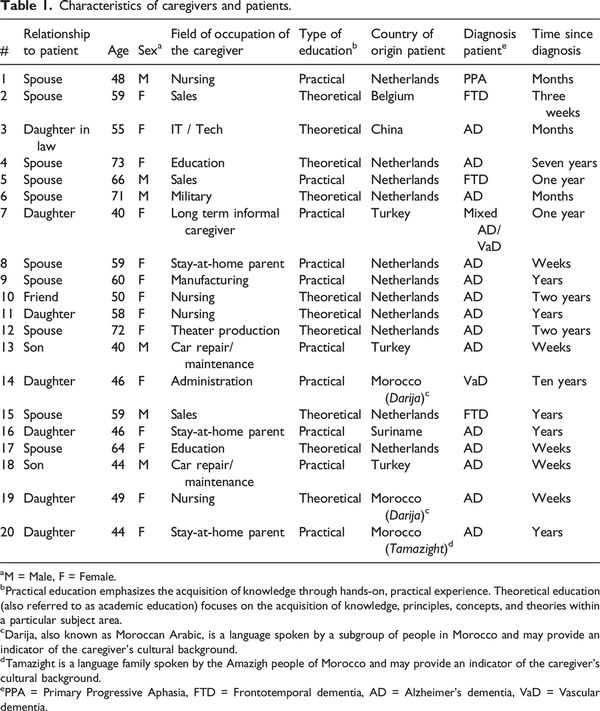

Participant characteristics

Demographic data were collected for all participants (see Table 1). The sample consisted of patients born in different countries (with presumably different cultural backgrounds): the Netherlands, Belgium, Turkey, Morocco, China, and Suriname. In this study, interviews were conducted with 11 caregivers of native Dutch patients and 9 caregivers of patients with a migration background, with the aim of capturing a broad range of experiences and perspectives. The average age of the participants was 55 years (range 40–73 years) and the sample consisted of both male (n = 6) and female (n = 14) caregivers. Half of the participants were spouses (n = 10), eight were adult children, one participant cared for her father-in-law, and one person identified as the patient’s friend. In the case of the culturally diverse patients, caregivers were often adult children, while the caregivers of Dutch patients were often spouses. Half of the participants (n = 10) cohabited with the person with dementia. Most of the participants had no prior experience with caregiving nor had worked as a healthcare professional. Most patients were diagnosed with Alzheimer Disease Dementia (n = 14), but caregivers for patients with Frontotemporal Dementia (n = 3), Primary Progressive Aphasia (n = 1), Vascular Dementia (n = 1) and Mixed Dementia (Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Dementia, n = 1) are also represented in this sample. Caregivers assisted in instrumental activities of daily living (iADL), such as in finances, but some also provided extensive help with most activities of daily living (ADL), such as washing and getting dressed. As the interviews progressed, recurring themes related to caregiving experiences, challenges, and coping strategies became evident across both caregiver groups, signaling that key aspects of the research questions had been sufficiently addressed. At this point, the decision was made to halt further data collection, in line with the principle of data saturation.

Ethical considerations

All participants provided written consent prior to the interviews. In each case, the informed consent form was either distributed via email beforehand or presented in person prior to the interview, at which time participants signed the document. After the study was completed, the audio recordings were destroyed. Only the transcripts are retained for scientific purposes as noted and in accordance with the outline in the informed consent form. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Erasmus Medical Center (MEC-2018-1568).

Results

In this paper, we will present the results of the study by structuring them according to the following four themes identified in the study:

1.) Motivators to providing care

2.) Cultural perspectives on caregiving

3.) The role of spirituality and religion in caregiving

4.) Optimizing the care context for the caregiver

Theme 1: Culturally shared motivators to providing care

A shared history

A variety of culturally shared reasons were reported for providing care for the person with dementia. A predominant motivator for informal caregivers was having an especially close relationship with the person with dementia. In those cases, providing care was perceived as self-evidently stemming from a shared history:

‘It’s been good for 48 years, and it will be good for another 48 if it continues like this. I know exactly how she thinks. I know exactly what she is like, her behavior. I understand her. I know how to interact with her.’ (Caregiver 5, Dutch heritage)

The shared history provided the caregiver with knowledge about the person with dementia and what the person with dementia would consider good care. The caregiver explained that this shared history enabled them to facilitate the best care based on all the details and intricacies they learned about the person with dementia throughout their lives. Some caregivers highlighted this as an important reason to provide care, as the person with dementia often could no longer advocate for their own wishes and needs due to the severity of the disease.

‘She is my mother, and I don’t know if there is anyone that would know her like I do. Especially now that my father has passed away. I know the soap that she likes to use when showering. (…). We also eat halal and I am not sure if others that don’t have our way of living would understand her.’ (Caregiver 13, Turkish heritage)

Reciprocity

Reciprocity was another cross-cultural reason for caregivers to provide care. Nearly all participants mentioned that they have in the past received care in some form from the person with dementia. For married couples, this was often considered in the light of the pledge made to one another:

‘We are married. Simple as that. You are there for each other in good and bad times. As long as it is possible for him to live at home, I will do my best to provide the best possible care.’ (Caregiver 12, Dutch heritage)

Adult child-parent care relationships were defined more often by how parents previously cared for the child, with children considering it ‘their turn now’ to provide care:

‘She has always given me a lot of love and care. I cannot leave her without any care. She is my mother.’ (Caregiver 14, Moroccan heritage)

Interestingly, some of the caregivers in child-parent care relationships emphasized the special bond they had with their parents in comparison with the relationship their siblings had with their parent. Some participants emphasized the amount of emotional support they had received from their parent during challenging times and how that strengthened their relationship:

‘She cared for me emotionally when one of my kids was in the hospital for a longer period of time. That was maybe one of the last times that she was very aware and caring towards someone before the dementia became noticeable. I had to go to the emergency room with my child and she really motivated me to stay strong for her. To make sure to be consistent with my prayers and that actually helped. I can never repay her for all the care and support that she provided during that difficult time.’ (Caregiver 13, Turkish heritage)

Many caregivers considered the element of not being able to (ever) ‘repay’ the person with dementia for the care they provided regardless of the type of care relationship.

Although reciprocity can be an important driver to provide care in families, other motives may come into play as well. One of the caregivers included in this study provided care for her father-in-law, who had always lived in China until he developed dementia. During the interview it emerged that the caregiver had had a complex relationship with her father-in-law in the past. When asking her about her motives to provide care, she stressed their family ties:

‘It is human nature. Without my help he can’t do anything. He doesn’t speak Dutch and because of the dementia his Chinese isn’t good either. He can’t explain things very well. He just needs somebody around and I do my best. (…) He is the grandfather of my son.’ (Caregiver 3, Chinese heritage)

Theme 2: Cultural perspectives on caregiving

Caregivers of native Dutch patients—who might be presumed to be on the individualistic side of the individualistic-collectivistic continuum—more commonly reported considering care options outside of the home setting, such as adult day care services (in Dutch: “dagbesteding”) for the person with dementia:

‘There are still some things he can do. (…) To give myself a break I have searched for some forms of adult day care so I can have a few hours to myself. (…) I have also considered a long-term care facility and googled it. Just in case, so I know what the possibilities are.’ (Caregiver 4, Dutch heritage)

‘Look, when the time comes, I believe we will need to carefully consider what the right balance is considering our lifestyle. [We will need to evaluate] what care I can provide, and what care I cannot, and [consider] how I can maintain my own freedom in my own home while my husband becomes dependent on assistance. (…) I think considering care options outside the home can be a solution for that.’ (Caregiver 1, Dutch heritage)

These quotes show that caregivers of native Dutch patients were actively considering the use of specialized services, both now and in the near future. These considerations were driven by their desire to take a break from caregiving at times, but also to maintain some degree of autonomy over their own lives. They viewed care options outside the home as potential solutions to temporarily alleviate the caregiver burden they were experiencing.

In contrast, the caregivers of the patients from presumably more collectivist cultures did not spontaneously mention long-term care facilities or adult day care, but rather highlighted the number of individuals available to provide care in their personal network:

‘We are with 5 kids. I don’t think it is necessary to look into long-term care facilities. (…) We can do it ourselves.’ (Caregiver 14, Moroccan heritage)

This quote illustrates that the caregiver is prioritizing the quantity of available caregivers within the family over the potential benefits of professional care in terms of quality and relief. As mentioned earlier, she highlighted the importance of reciprocity in the care relationship for her mother, and it is likely that she expects this same reciprocity towards her mother from the other family members. This might be an explanation for why long-term care facilities or adult day care are not being considered. The culturally diverse caregivers also highlighted their commitment and willingness to persevere in the face of difficulties:

‘When I relate it to caring for my mother, I just know what needs to be done (…). Sometimes these are less pleasant things, but what can I do? It is a commitment I made. You already know at the outset what kind of process it can become.’ (Caregiver 13, Turkish heritage)

‘It is important to care for your parents. For how long will she [her mother] still be around? (…) I can persevere a little longer, so that at least she receives care from someone close to her.’ (Caregiver 19, Moroccan heritage)

Theme 3: the role of spirituality and religion in caregiving

Some of the caregivers mentioned that spirituality and religion aided in creating a calm and stable state of mind throughout the caregiving experience. This was a common sentiment particularly among caregivers with a migration background. It helped them see the bigger picture:

‘You have more understanding for the situation of the other. (…) If you are very religious you will realize that He [Allah – God] will give you the ability to stay patient and do the job. He will not give you something that you can’t handle. That is a comforting thought.’ (Caregiver 14, Moroccan heritage)

Although religion was recognized as a way to cope with difficult situations, it was not necessarily identified as a reason to provide care. One of the participants who considered himself to be a religious person (i.e. Muslim) mentioned that he did not attribute providing care for his mother to his religion. Instead, he stressed his intrinsic motivation to provide care:

‘I am a Muslim. It is important to care for your parents because they are held in high regard. Well, I find it difficult to say that I only provide care for my mother because of my religion. That really isn’t just the reason for doing it. I really am willing to do it [provide care] and I do it in an attentive way. (…) I am just really motivated to do this for her.’ (Caregiver 13, Turkish heritage)

One caregiver viewed spirituality as a way of living in the present moment and applied similar reasons to their approach to caregiving:

‘I would say that I am spiritual to some extent. (…) I let everything wash over me for some reason. You can keep overthinking the situation as it is right now, but essentially those thoughts will change nothing. (…) So I live in the moment.’ (Caregiver 4, Dutch heritage)

Some caregivers did not identify with a specific form of religion or spirituality – this was common among caregivers without a migration background – but mentioned adhering to a personal philosophy of life:

‘It is more a way of life. The things you do for others should have a positive effect on them. Treat others the way you want to be treated. (…) Or maybe we should care for others in the same way you would like to be cared for yourself. That is the essence.’ (Caregiver 10, Dutch heritage)

This caregiver further elaborated on their view by stating the following:

‘Even if she will not remember a thing and will start cussing me out, I will always remain her friend and help her with whatever she needs. (…) My mother-in-law had a friend who also had dementia and when I once asked her why she doesn’t visit, she just said, without shame, that she [her friend] had nothing left to offer. (…) I would be terrified if I would live life that way.’ (Caregiver 10, Dutch heritage)

Even though some caregivers may not formally consider spirituality or religion a core element in their lives, they may still adhere to a certain philosophy on life in providing care.

Theme 4: Optimizing the care context for the caregiver (facilitators)

The family environment

Caregivers reported a variety of facilitators that enabled them to provide care for the person with dementia. One facilitator that was mentioned often by adult children (in this study, mostly caregivers with a migration background) involved the provision of assistance from the caregiver’s spouse (or children), contributing to the smoother operation of their own family life:

‘My sisters both have daughters who can help out if there would be an important appointment. (…) I have also asked my daughters to stay with my mother when I needed to go to a family party.’ (Caregiver 14, Moroccan heritage)

‘I have a fantastic partner. Because of him all of this is possible. (…) If my husband would not be so understanding, we would not be able to provide care in the way that we do. Especially, with me also sleeping some nights of the week with my mom at her home. (…) He keeps the family running while I provide care for my mother.’ (Caregiver 14, Moroccan heritage)

When asked directly how a caregiver’s family life impacts the level of caregiver burden, caregivers 13, 14, and 19 mentioned that knowing that everything is running smoothly at home would be ‘one less thing’ that they would need to worry about.

Structure and routine to prevent restlessness and confusion

Caregivers of patients with a recent diagnosis of dementia across different cultural backgrounds reported difficulties coping with the unpredictability of the person with dementia:

‘I don’t know what goes on in her head sometimes. It is very messy up there which makes her very unpredictable. (…) Just recently, there was a moment that she forgot where we live. She ended up in a completely different street from the one we live in. (…) At those times I really ask myself: how [ can she think like that]?’ (Caregiver 6, Dutch heritage)

The caregivers with a longer experience in providing care for the person with dementia would also highlight the patient’s unpredictable behavior. Respondent 19 explained how they coped in the following way:

‘In the first few weeks my mother would be very restless for no apparent reason. She ate and bathed, but still, she remained restless. I could not really figure out why she would be restless because she didn’t give me a coherent answer when I would ask what she wanted. (…) Later, by chance, we found out that when we moved her favorite rug she became restless. The same with changing up her favorite hijab [headscarf]. (…) At the time I didn’t realize that she would attach so much importance to that.’ (Caregiver 19, Moroccan heritage)

Some caregivers also pointed out the importance of having a good structure/schedule in place for the caregiving tasks and additional activities for the person with dementia. This would help them to optimize the care for the person with dementia and also make the caregiving experience more manageable:

‘Our week has a clear schedule. I spend a full day with her on Thursdays. For the rest of the week, I have a clear overview of when and for how long someone is with her. That could be either her receiving more care at home, as well as her going to an adult day care service. (…) Fridays are normally the days I have to myself.’ (Caregiver 11, Dutch heritage)

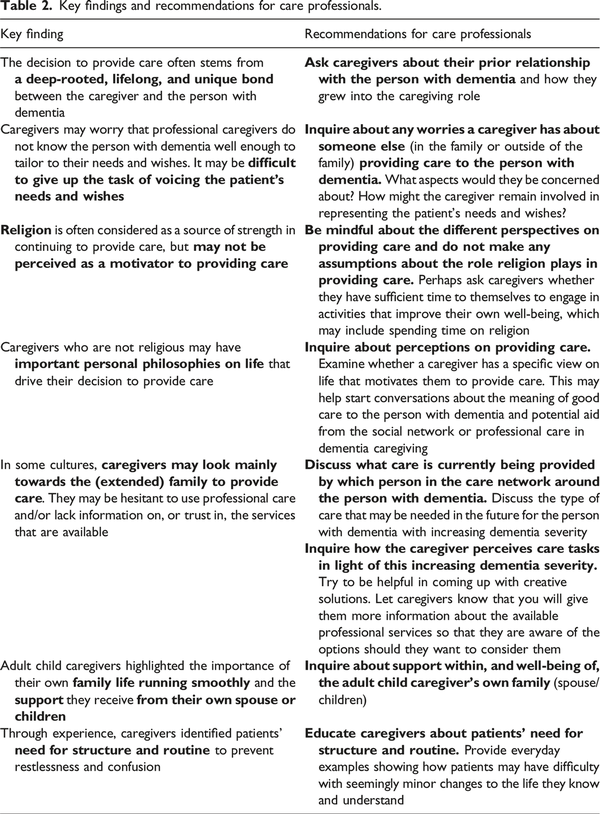

Summary of the main findings and recommendations

Several of the quotes provided by the caregivers in this study provide an insight into ways health care professionals might tailor their services to suit the diverse needs of these caregivers. Table 2 provides an overview of our main findings in the column on the left, followed by our recommendations for care professionals for clinical practice on the right.

Discussion

This study explored the variation in motivators and facilitators for providing dementia care in a home setting reported by informal caregivers with diverse cultural backgrounds (Dutch, Belgian, Turkish, Moroccan, Surinamese, and Chinese heritage). Four main topics emerged from the qualitative interviews: culturally shared motivators to providing care, culture specific perspectives on caregiving, diverse perspectives on the role of religion and personal philosophies, and ways to optimize the care context.

Motivators for providing care

The main motivator that informal caregivers mentioned was the close relationship they had developed with the person with dementia over time and their unique knowledge of the other. Providing care was also perceived from the perspective of reciprocity. This shared history was often seen as the basis of the reciprocity and generalized to some extent across the different care relationships and across cultures. Caregivers specifically stressed how they had intricate knowledge about the person with dementia and how this contributed to optimal care.

Caregivers highlighted their role in communicating the needs and wishes of the person with dementia. Our study echoes findings from Belgium, where caregivers reported that older Moroccan individuals with dementia were not able to voice their needs to healthcare professionals, resulting in worries about entrusting older Moroccans to the care of healthcare professionals (). This trend may also illustrate a key difference in caregiving approaches, where informal caregivers—with their closer connection to the individual with dementia—are better attuned to their needs, whereas professional caregivers may struggle to recognize these needs due to the absence of that unique bond. As recommended by , professional caregivers should actively engage informal caregivers in the care process, ensuring it is tailored to the needs and preferences of the person with dementia. In particular, our study highlights the importance of incorporating discussions about how family members can continue to represent the needs and wishes of the person with dementia, while also addressing the specific concerns caregivers may have in various areas of care. show that each caregiver may serve a different role, such as the ‘coordinator’ of care, the ‘main nurse’ providing day-to-day care, the ‘assistant’ who supports the main nurse, and the legal representative fulfilling all administrative responsibilities and serves as a (legal) guardian. Such knowledge on how care is organized within the family may be relevant for care professionals to identify how best to support the system of informal caregivers.

Reciprocity: A double-edged sword

Our study highlighted the unique relationships between the person with dementia and their caregivers. Some adult child caregivers stressed that they could never repay the person with dementia for the care they provided to them when they were younger. This theme of reciprocity may therefore present as a double-edged sword, motivating caregivers but also potentially resulting in caregivers providing care beyond their personal limits, which could in turn result in emotional and physical exhaustion. Such exhaustion is a common outcome of caregiving, particularly in culturally diverse populations (; ; ), although also evident among Dutch caregivers (; )—suggesting that the pressures of caregiving transcend cultural boundaries. Thus, while the theme of reciprocity may drive caregivers’ dedication, it can also contribute to burnout and exhaustion when caregivers exceed their own limits in an effort to repay their loved ones.

The complexity of caregiving relationships

Although reciprocity and a unique relationship were often mentioned, motives to provide care may not always stem from an intimate and loving connection that the caregiver and person with dementia share or once shared. Healthcare professionals should consider the multifaceted family dynamics which have led to the caregiver taking up the responsibility to provide care for the person with dementia. It is often a sequence of events that willingly or unwillingly led to a caregiver taking up their role (). It may help to ask caregivers how they came to be the (main) caregiver and what their prior bond with the person with dementia was like. Previous research in diverse populations has highlighted moral framing rules that may lead caregivers to provide care (). Future research might investigate whether caregivers who provide care out of feelings of (filial) duty experience caregiver burden differently than caregivers who underscore their unique bond with the person with dementia.

In this study, caregivers who were likely from collectivistic cultures were less inclined to (spontaneously) mention professional care/assistance when discussing care for the person with dementia. The question arises whether this stems from a reluctance towards professional help () or from a lack of knowledge of, or perhaps limited trust in (the quality of), professional care services (; ). Another explanation could be that caregivers may not always know much about dementia (; ), how dementia progresses, and which care challenges they may encounter in the future. Alternatively, families may make use of other practices, such as 24 hour rotational care, as opposed to using formal care, or they may perceive providing care as a familial responsibility (). Formal care may also be perceived as inferior in quality to family care ().

The role of religion and spirituality in caregiving

A number of caregivers, most of them with a migration background, expressed a need for spirituality and religion to continue to provide care. Various studies have considered religion or spirituality as an important aspect in the caregiving experience (; ). Some studies even identified religion as a main or predominant reason to provide care, with one interviewee stating, “If it’s not for Allah, then you wouldn’t do it” (). In contrast, when we specifically inquired about the role of religion in our study, we found that religion was often described as a source of strength, making it easier to persevere in providing care, rather than being a main reason for providing care. Raising this question often resulted in caregivers mainly elaborating on their personal, intrinsic motivation. Based on our findings, caregiving should not be perceived as universally driven by religious beliefs across all religious caregivers. Furthermore, religion and spirituality in our study did not always cover all the ways in which people give meaning to their life and the caregiving experience; some may adhere to specific life philosophies without identifying with any particular religion.

Facilitators to care

Last, caregivers highlighted facilitators to care, which included support received from their own spouse or children, as well as adhering to routines and structure to prevent the patient becoming restless, confused, or showing unpredictable behavior. This was especially relevant for adult children (who, in this study, often had a migration background) providing care for their parents. Care professionals may support caregivers by providing education about the behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, other dementia related symptoms, and the dementia trajectory. Furthermore, interventions are slowly being developed to assist culturally diverse families in providing care; for example, a pilot study in Denmark revealed that caregivers appreciated having someone to turn to for questions on “smaller everyday issues” in providing care, as well as someone to help with “coordination of care services” ().

Strengths and limitations

The findings of this qualitative study contribute to the literature by offering insights into motivators and facilitators to providing care. Strengths of this study include the inclusion of caregivers with different care relationships (i.e. spouse, adult-child, and friend), as well as the different dementia diagnoses and countries of origin of the patients (including caregivers of both native Dutch patients and patients with a migration background). Furthermore, our study included a number of male caregivers, a group that was not represented in previous studies (e.g. in ; ). Another strength was that interviews were conducted by a bilingual and bicultural researcher, while coding was conducted by researchers with different cultural backgrounds. A limitation of this study is that we conducted all interviews in Dutch, which may have influenced the way caregivers expressed their experiences. Furthermore, a small subset of the interviews was conducted by phone or through videoconferencing, which could potentially have impacted the dynamics during the interview. In some cases, using such methods was necessary, because of logistical barriers or the caregiver not being able to host the researcher at home without the person with dementia present. This would hinder talking freely about their experiences. A third limitation is that the adult-child caregivers often had a migration background, while the caregivers of patients born in the Netherlands were spouses. This makes it difficult to disentangle the effects of migration background/culture from the relationship type and the age of the caregiver. Finally, we examined the effects of culture by including participants with several different cultural backgrounds in our study. As the sample was selected to be as diverse as possible to uncover as many different perspectives as possible, we included only small numbers of participants per cultural group. The disadvantage of this strategy is that some culture-specific aspects particular to one cultural group may have been missed. A follow-up study in specific, homogenous cultural groups may be needed to examine such culture-specific factors in extensive detail.

Conclusions and recommendations

In summary, the number of diverse older adults with dementia will increase over the next decade; current policies directed towards aging in place can only succeed if the experiences of culturally diverse informal caregivers are taken into account, lifting barriers, but also promoting facilitators to provide care. This study highlights four relevant themes in this context: 1) motivators to provide care, 2) cultural perspectives on caregiving, 3) the role of spirituality and religion in caregiving and 4) optimizing the care context. Several recommendations within the four themes were made that can help healthcare professionals gain a better understanding of the broader care system in which informal caregivers operate. This will hopefully lead to better support of the culturally diverse, informal caregivers devoting so much of their time and energy to caring for their loved one with dementia.

Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: SF was consultant to Biogen in 2022, and SF and JP receive royalties on two neuropsychological tests (Five Digit Test and Visual Association Test; all paid to their organization). NL, FF and RvB report no potential conflicts of interest.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was supported by ABOARD, a partnership between the Dutch Medical Research Council ZonMw, (#73305095007) and Health∼Holland, Topsector Life Sciences & Health (#LSHM20106).

Research data Transcripts.

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Ahmad M., van den Broeke J., Saharso S., Tonkens E. (2020). Persons with a migration background caring for a family member with dementia: Challenges to shared care. The Gerontologist, 60(2), 340–349. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnz161.

- Ahmad M., van den Broeke J., Saharso S., Tonkens E. (2022). Dementia care-sharing and migration: An intersectional exploration of family carers’ experiences. Journal of Aging Studies, 60(1). DOI: 10.1016/j.jaging.2021.100996.

- Alexander K., Oliver S., Bennett S. G., Henry J., Hepburn K., Clevenger C., Epps F. (2022). “Falling between the cracks” Experiences of Black dementia caregivers navigating U.S. health systems. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 70(2), 592–600. DOI: 10.1111/jgs.17636.

- Alzheimer Europe. (2020). Intercultural dementia care: A guide to raise awareness amongst health and social care workers. Alzheimer Europe. Retrieved 11-04-2024 from https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/resources/publications/2020-alzheimer-europe-guide-intercultural-dementia-care-health-and-social?language_content_entity=en

- Alzheimer Nederland. (2024). Feiten en cijfers over dementie. Alzheimer Nederland. Retrieved 11-04-2024 from https://www.alzheimer-nederland.nl/dementie/feiten-en-cijfers-over-dementie

- Alzheimer Europe. (2018). The development of intercultural care and support for people with dementia from minority ethnic groups. Retrieved 11-04-2024 from https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/alzheimer_europe_ethics_report_2018.pdf

- Babbie E. R. (2020). The practice of social research (13 ed., Vol. 1). Cengage Learning.

- Berdai Chaouni S., De Donder L. (2019). Invisible realities: Caring for older Moroccan migrants with dementia in Belgium. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 18(7-8), 3113–3129. DOI: 10.1177/1471301218768923.

- Bolt L. L. E., Verweij M. F., Van Delden J. J. M. (2010). Ethiek in praktijk (7th ed.). Van Gorcum.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Mensen met herkomst buiten Nederland wonen relatief vaak in grote steden. Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2022/48/mensen-met-herkomst-buiten-nederland-wonen-relatief-vaak-in-grote-steden

- Central Bureau of Statistics. (2024). Ouderen. Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 11-11-2024 from https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/visualisaties/dashboard-bevolking/leeftijd/ouderen

- Duran-Kirac G., Uysal-Bozkir O., Uittenbroek R., van Hout H., Broese van Groenou M. I. (2022). Accessibility of health care experienced by persons with dementia from ethnic minority groups and formal and informal caregivers: A scoping review of European literature. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 21(2), 677–700. DOI: 10.1177/14713012211055307.

- Franzen S., Eikelboom W. S., van den Berg E., Jiskoot L. C., van Hemmen J., Papma J. M. (2021). Caregiver burden in a culturally diverse memory clinic population: The caregiver strain index-expanded. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 50(4), 333–340. DOI: 10.1159/000519617.

- Goudsmit M., van de Vorst I., van Campen J., Parlevliet J., Schmand B. (2022). Clinical characteristics and presenting symptoms of dementia - a case-control study of older ethnic minority patients in a Dutch urban memory clinic. Aging and Mental Health, 26(11), 2277–2284. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2021.1963416.

- Jensen C. J., Inker J. (2015). Strengthening the dementia care triad: Identifying knowledge gaps and linking to resources. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias, 30(3), 268–275. DOI: 10.1177/1533317514545476.

- Knight B., Keane N., Benea D., Stone R. (2022). Values and the experience of family care-giving: Cultural values or shared family values? Ageing and Society, 44(1), 61–78. DOI: 10.1017/s0144686x2200006x.

- KNMG. (2024). KNMG-richtlijn behandelingsovereenkomst, Retrieved 11-04-2024. https://www.knmg.nl/actueel/publicaties

- Markus H. R., Kitayama S. (1991). Cultural variation in the self-concept. In Strauss J., Goethals G. R. (Eds.), The self: Interdisciplinary approaches. Springer. DOI: 10.1007/978-1-4684-8264-5_2.

- Miller M., Neiterman E., Keller H., McAiney C. (2024). Being a husband and caregiver: The adjustment of roles when caring for a wife who has dementia. Canadian Journal on Aging, 1–10. DOI: 10.1017/s0714980824000291

- Nielsen T. R., Nielsen D. S., Waldemar G. (2021). Barriers in access to dementia care in minority ethnic groups in Denmark: A qualitative study. Aging and Mental Health, 25(8), 1424–1432. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2020.1787336.

- Nielsen T. R., Waldemar G., Nielsen D. S. (2021). Rotational care practices in minority ethnic families managing dementia: A qualitative study. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 20(3), 884–898. DOI: 10.1177/1471301220914751.

- Parlevliet J. L., Uysal-Bozkir Ö., Goudsmit M., van Campen J. P., Kok R. M., Ter Riet G., Schmand B., de Rooij S. E. (2016). Prevalence of mild cognitive impairment and dementia in older non-western immigrants in The Netherlands: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(9), 1040–1049. DOI: 10.1002/gps.4417.

- Phillipson L., Jones S. C., Magee C. (2014). A review of the factors associated with the non-use of respite services by carers of people with dementia: Implications for policy and practice. Health and Social Care in the Community, 22(1), 1–12. DOI: 10.1111/hsc.12036.

- Poisson V. O., Poulos R. G., Withall A. L., Reilly A., Emerson L., O'Connor C. M. C. (2023). A mixed method study exploring gender differences in dementia caregiving. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 22(8), 1862–1885. DOI: 10.1177/14713012231201595.

- Rathier L. A., Davis J. D., Papandonatos G. D., Grover C., Tremont G. (2015). Religious coping in caregivers of family members with dementia. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 34(8), 977–1000. DOI: 10.1177/0733464813510602.

- Rijksoverheid. (2022). Programma Wonen, Ondersteuning en Zorg voor Ouderen (WOZO). Rijksoverheid. Retrieved 11-04-2024 from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/documenten/rapporten/2022/07/04/wozo-programma-wonen-ondersteuning-en-zorg-voor-ouderen

- Scherr S., Reifegerste D., Arendt F., Van Weert J. C. M., Alden D. L. (2022). Family involvement in medical decision making in Europe and the United States: A replication and extension in five Countries. Social Science & Medicine, 301, 1–7. DOI: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114932.

- Schulz R., Eden J. (2016). Families caring for an aging America. The National Academies Press. DOI: 10.17226/23607.

- Shibusawa T. (2024). Working with families in an aging society. World Social Psychiatry, 6(1), 16–19. DOI: 10.4103/wsp.wsp_69_23.

- Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau. (2020). Blijvende bron van zorg: Ontwikkelingen in het geven van informele hulp. Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau. Retrieved 11-04-2024 from. https://www.scp.nl/publicaties/publicaties/2020/12/09/blijvende-bron-van-zorg

- Stuckey J. C. (2003). Faith, aging, and dementia: Experiences of Christian, Jewish, and non-religious spousal caregivers and older adults. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 2(3), 337–352. DOI: 10.1177/14713012030023004.

- Ten Have H. A. M. J., Ter Meulen R. H. J., Van Leeuwen E. (2009). Medische ethiek (3th ed.). Van Loghum.

- Van Der Lee J., Bakker T. J. E. M., Duivenvoorden H. J., Dröes R. (2017). Do determinants of burden and emotional distress in dementia caregivers change over time? Aging and Mental Health, 21(3), 232–240. DOI: 10.1080/13607863.2015.1102196.

- Van Der Weijden T., Van Der Kraan J., Brand P. L. P., Van Veenendaal H., Drenthen T., Schoon Y., Tuyn E., Van Der Weele G., Stalmeier P., Damman O. C., Stiggelbout A. (2022). Shared decision-making in The Netherlands: Progress is made, but not for all. Time to become more inclusive to patients. Zeitschrift fur Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualitat im Gesundheitswesen, 171(1), 198–204. DOI: 10.1016/j.zefq.2022.04.029.

- Van Wezel N., Francke A. L., Kayan Acun E., Devillé W. L., van Grondelle N. J., Blom M. M. (2018). Explanatory models and openness about dementia in migrant communities: A qualitative study among female family carers. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 17(7), 840–857. DOI: 10.1177/1471301216655236.

- Van Wezel N., Francke A. L., Kayan-Acun E., Ljm Devillé W., van Grondelle N. J., Blom M. M. (2016). Family care for immigrants with dementia: The perspectives of female family carers living in The Netherlands. Dementia: The International Journal of Social Research and Practice, 15(1), 69–84. DOI: 10.1177/1471301213517703.

- Zorgstandaard Dementie. (2020). Zorgstandaard Dementie 2020 (p. 26). Retrieved 11-04-2024 from https://www.zorgstandaarddementie.nl/zorgstandaard