Introduction

There are currently around 55 million people living with dementia globally (). In most cases, people are diagnosed with dementia in advanced age, i.e., 65 years and older (). Young-onset dementia refers to dementia symptom onset before age 65 (). Young-onset dementia accounts for around 5% of all cases of dementia (). However, this number may be underestimated. A recent systematic review drawing from 95 studies estimated the global prevalence of young-onset dementia to be 119.00 per 100,000 population (). Informal carers of persons with young-onset dementia are usually spouses or family members (). A dementia diagnosis at a younger age can bring several challenges compared to a diagnosis at an older age for both the person with young-onset dementia and the carer. Carers and people with young-onset dementia may encounter inverse ageism; they may be raising a family, are often employed, could be looking after ageing parents, have financial responsibilities such as a mortgage, are generally physically fitter, may spend a drawn out time in the community post-diagnosis, and the person with potential young-onset dementia can face lengthy diagnosis outlets (; ; ; ). Furthermore, available support services might not be appropriate for this younger population, and therefore, carers and people with young-onset dementia might not willingly access the available services (). In addition, there appear to be limited support services available specifically for carers of people with young-onset dementia (). However, although the carers of this population are likely to be younger and more adept at using technologies and the internet, it is unclear whether they find specific telephone or online support programs or assistive technologies to assist their caregiving. Furthermore, although there are benefits to using technology, there are also mixed findings. One of the key concerns is the high cost of technology, and there are worries that not all technology is suitable for everyone to use (). This review aimed to identify the telephone and online support programs and assistive technologies that informal carers of people with young-onset dementia found useful.

Telephone and online support programs provide information and support to family carers (). Assistive technologies are “any item, piece of equipment, or product, whether acquired commercially, modified, or customized, that is used to increase, maintain, or improve functional capabilities of individuals with disabilities” (, p. 97). Assistive technology is categorised as low technology that is low-cost and relatively easy to use. Medium technology can be battery-operated or simple electronic items. Whereas high technology includes computers and sophisticated electronics. This type of technology can also include communication technology ().

There is growing evidence that technologies may help carers of older people with dementia manage care (; ). For example, digital technologies such as tablets may assist people with mild dementia with Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL), and as a result, this may also support carers by reducing their burden (, ; ). Digital technologies such as iPads and smart phones also helped people with dementia and their carers during the COVID-19 pandemic connect and engage with health professionals, friends, and family (). Assistive technologies such as electronic calendars may also help carers with time management (). Furthermore, carers may opt to receive support from telephone or online support programs to manage the care burden. Technologies such as fall alarms and home monitoring have been used to monitor the safety of people living with dementia (; ). While regarded positively, ethical issues have also been raised when monitoring people at home (). Even though technologies seem to be gaining momentum in dementia care generally (), it is unclear whether telephone and online support programs or assistive technologies will benefit carers of people with young-onset dementia or if this population has specific technology needs that are not being addressed.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first systematic review that identifies telephone and online support programs and assistive technologies that informal carers assessed to assist them with caring for people with young-onset dementia. The main research question is:

• What telephone and online support programs and assistive technologies do carers of people with young-onset dementia find helpful in supporting caregiving?

Design

A systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines ().

Search strategy

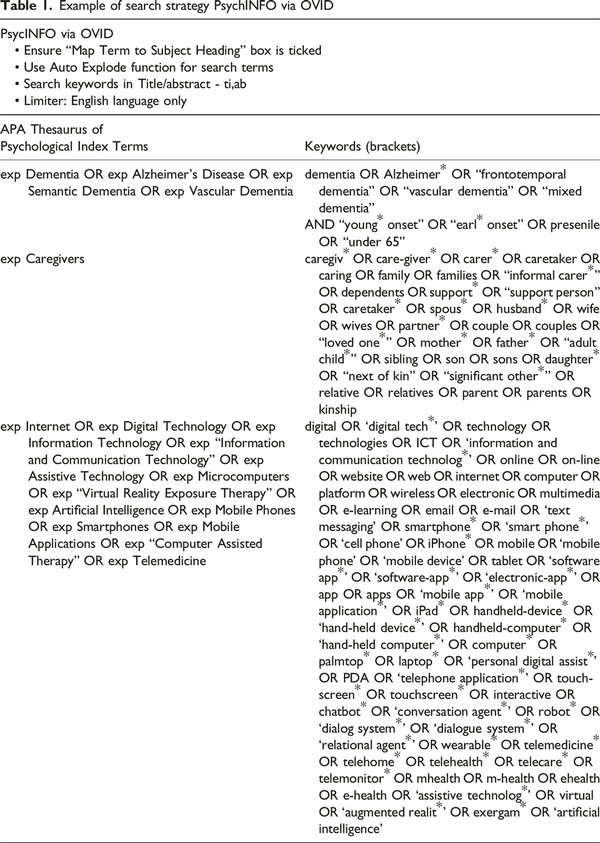

In consultation with a health librarian, we developed the database searches. Five English databases were searched, including PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science, in October 2023. Additionally, the reference lists of eligible studies and reviews were manually screened to identify further studies. Search terms used were synonyms and derivates of the following keywords: “dementia,” “Alzheimer,” “young onset”, “early onset”, “caregiver”, “technology”. Full details of the search strategy used in PsychInfo are provided in Table 1.

The keywords and MeSH terms (combined using Boolean operators) were searched in the title and abstract to avoid missing relevant literature. To include as many papers as possible, the literature search covered from the inception of relevant research to October 2023.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they met the following inclusion criteria:

Population: The focus was on carers of people with young-onset dementia (i.e., the population of interest), and research was undertaken in all settings, such as community (home), care facilities, or hospitals.

Intervention: The intervention evaluated the outcomes of digital technologies (single or multi-component interventions, e.g., digital component/s only or combined with face-to-face sessions).

Outcome: Reported peer-reviewed research results based on quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods studies.

Timeframe for follow-up: There was no timeframe for follow-up.

Publication language: The research was published in English in a peer-reviewed publication.

Studies were excluded if:

Population: The main focus was on populations other than carers of people with young-onset dementia.

Intervention: The intervention did not include telephone or online support programs or assistive technologies.

Outcome: The paper did not report empirical findings.

Publication language: The research was published in a language other than English, including reviews, protocols, reports, commentaries, editorials, conference abstracts, dissertations, book chapters, and textbooks.

Selection of publications

All retrieved articles were transferred into EndNote X8 as separate files, identified by their database names. All identified duplicates were removed automatically using the Find Duplicates function in EndNote X8, followed by additional manual removal. One reviewer (MS) screened all records for relevance to the topic and excluded articles based on title or abstract that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The selection was imported into Covidence, and two independent reviewers (MS, MQ) assessed full-text articles for eligibility. Because of the scarcity of studies in this area, all studies that met the inclusion criteria were included, including those where people with dementia included various diagnoses, and the results did not specify the findings specifically for carers of people with young onset dementia.

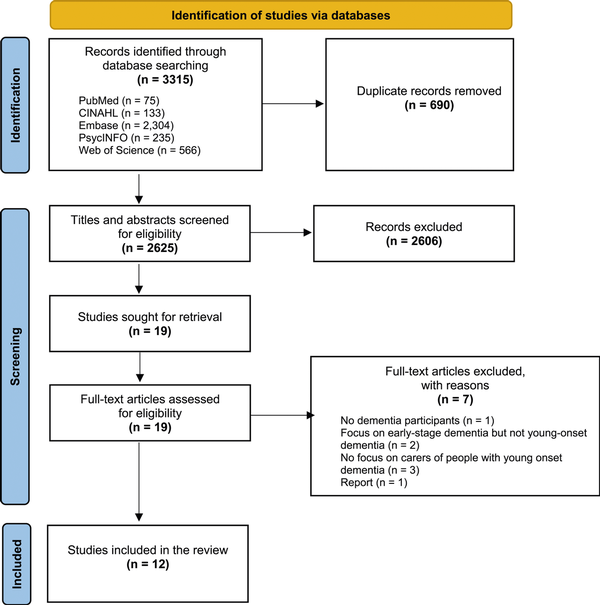

The review followed PRISMA guidelines () (see Figure 1). The systematic review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (International database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care, CRD42023478014.

Figure 1

Prisma flow diagram.

Data extraction and analysis

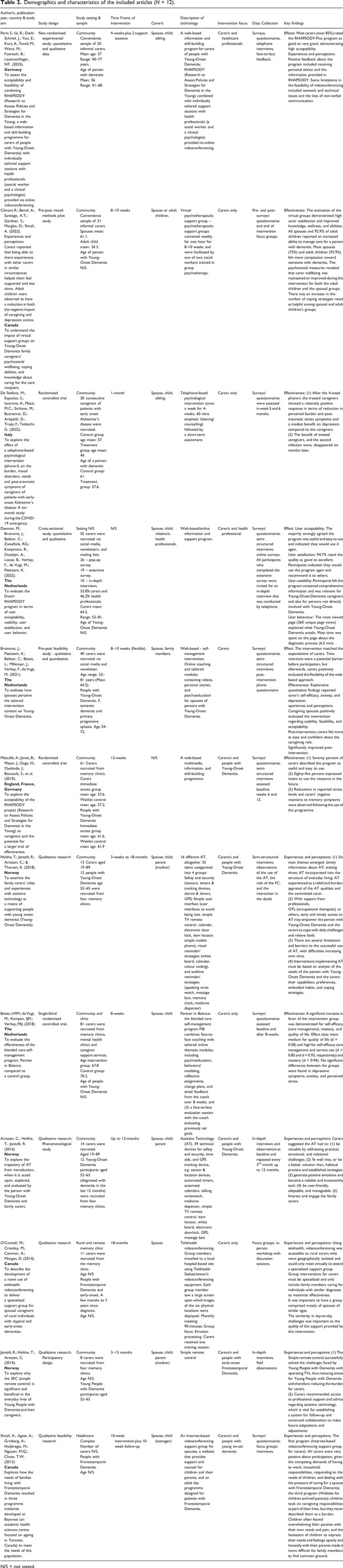

All authors were involved in data extraction using a table with subheadings (Table 2). The information extracted from the eligible articles for data synthesis included the title, authors, year of publication, country, study aims, study design, setting, timeframe, participants, digital technology, intervention focus, data collection and key findings. Data were extracted by four reviewers (MS, MQ, LP, NL), and a consensus review was undertaken until agreement was reached for an article’s final inclusion. Any discrepancies between researchers regarding inclusion were resolved through discussion between all authors (MS, MQ, LP, NL, WM).

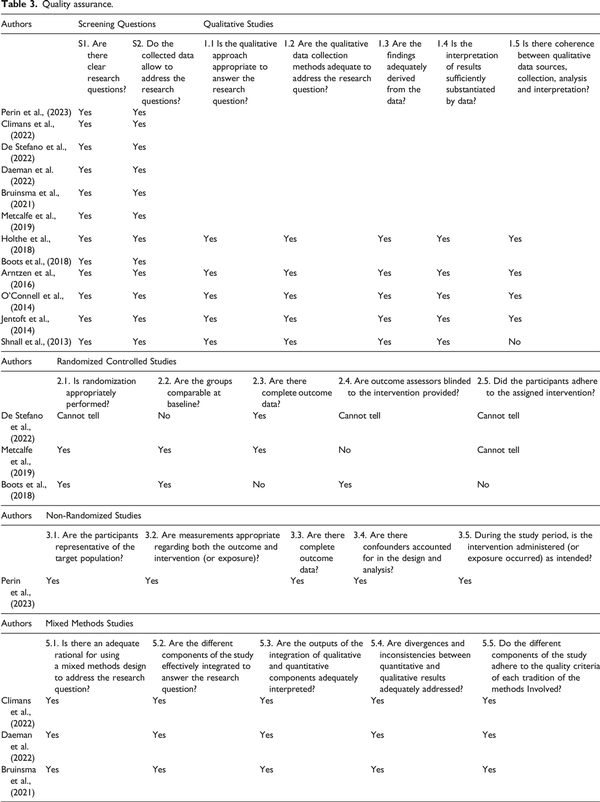

Quality appraisal

The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 was used to assess the included studies’ quality and risk of bias (). This tool is a well-established tool for reviewing the quality of study designs. We assessed for randomization, group comparability at baseline, availability of complete outcome data, the outcome of assessors’ blinding, and participants’ adherence to the intervention when assessing the quality of randomized control trials. In quantitative non-randomized studies, we assessed the sample representativeness of the target population, the use of measurements appropriate for both outcome and intervention, the availability of complete outcome data, accounting for confounders during design and analysis, and administration of the intervention as intended. One rater (MS) independently assessed the quality of the included studies. A second rater (MQ) then assessed a random sample of the articles to ensure agreement was reached. Where there was disagreement between the reviewers, a third reviewer (WM) appraised the paper, and a discussion took place to resolve any discrepancies (see Table 3).

Results

Study selection

A total of 3,315 studies were retrieved from five databases (PubMed, CINAHL, EMBASE, PsycINFO, and Web of Science), and after removing 690 duplicate records, a title and abstract screening excluded 2606 studies that did not meet the inclusion criteria. A full-text review of the remaining 19 studies was conducted against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A further seven studies were removed for the following reasons: did not include people with dementia (n = 1), focus on early-stage dementia but not young age (n = 2), did not focus on carers of persons with young-onset dementia (n = 3), and one was a report (n = 1). In total, 12 articles met our inclusion criteria and were included in this review (Figure 1).

Study characteristics

The studies were conducted in a small number of countries, predominantly in Europe (The Netherlands (n = 3), Norway (n = 3), Germany (n = 1), Italy (n = 1)), and one study was conducted in three countries, i.e. England, Germany, and France. The remaining three studies were conducted in Canada. Most of the studies were conducted in the community (n = 8), followed by the memory clinic (n = 1) and healthcare complex (n = 1). Two did not report the setting. There were a variety of designs. The main design was qualitative research (n = 5) followed by randomized controlled trials (RCTs) (n = 3), pre-post mixed methods (n = 3), and non-randomized quantitative and qualitative research (n = 1). The studies undertaken in The Netherlands, Norway and Canada were undertaken in each country by the same team of authors.

Participant characteristics

Most of the studies invited only informal carers to participate. The study sample included informal carers of people living with young-onset dementia, predominantly spouses, children, siblings, or relatives. One study () also included formal carers (health professionals), and another study () did not report the carers’ details (see Table 2).

Dementia type and severity

Although the focus was on carers of people with young-onset dementia, the most common type of dementia reported was Alzheimer’s disease, followed by Frontotemporal Dementia.

Technology type

The most frequent technologies were online support interventions that provided information and skill-building programs that were often accompanied by counselling sessions with health professionals (; ; ; ; ; ), virtual psychotherapy (), telephone-based psychological intervention (), various assistive technologies such as sensor and location devices, automated timers, mobile phone, automatic calendar, talking wrist watch, and medicine dispenser (; ), a simple TV remote control (; ), and telehealth (). Three of the studies assessed the same RHAPSODY program (; ; ).

Number and duration of technology sessions

The number and duration of the technology sessions varied between the publications. The length of the intervention ranged from 4 weeks to 10 weeks for 60 minutes of listening/counselling to a monthly 90-min meeting. did not report the length of the technology duration.

Carers training

The training of carers to use the technologies was reported in only one paper (). However, it is assumed that some form of training must have taken place to teach carers how to use the technologies.

Effect and effectiveness of technologies

All studies reported improved carer management following participation in the reported interventions. Positive outcomes included carer higher self-efficacy (; ), carer satisfaction and improved knowledge (), improved well-being and reduction in perceived carer burden and stress (; ; ; ), and reduced carer depression (; ; ) and anxiety (). There was also an increase in carer coping strategies related to online programs. However, did not find any significant differences between the intervention and control groups in depressive symptoms, anxiety, and perceived stress. In addition, carers rated the programs from good to very good, demonstrating high acceptability, satisfaction, and useability.

Quality assurance

All qualitative studies were reported to be of a high standard except for , who failed to provide quotation support for their analysis and interpretation. None of the RCTs were of a high standard. met only one criterion, and and met three of the five quality assurance criteria. were of a high standard in the non-randomized controlled studies, and all mixed methods studies (; ; ) were also ranked to be of a high standard (see Table 3).

Discussion

In this review, we aimed to understand the telephone and online support programs as well as assistive technologies that informal carers assessed as helpful when caring for people with young-onset dementia. However, this review is limited by the small number of studies from predominately Europe. This finding may be influenced by Europe being in the top five countries in the development of all 64 technologies and their substantial R&D investment (https://www.aspi.org.au/opinion/critical-technology-tracker-two-decades-data-show-rewards-long-term-research-investment). Furthermore, the small number of research teams suggest that such technologies and young-onset dementia are not topics of significant interest in the current dementia literature. Given the rarity of young-onset dementia; this topic might also not be attractive to research funders. This is disappointing, given the increasing number of people with young-onset dementia and the care burden for carers of this population. However, the apparent limited development of technologies for this population, and the difficulties in gaining a diagnosis, including long delays in receiving a diagnosis, may also have contributed to the low number of manuscripts regarding technology support. Furthermore, the lack of healthcare professional training in using these technologies and limited knowledge may also have exacerbated problems in encouraging carers to trial available technologies and creating new research opportunities (; ). In addition, caregivers are price-sensitive because of caregiving’s financial demands, which may also have contributed to the low number of technologies available for evaluation ().

As indicated in the results, all studies reported improved carer management following participation in the reported interventions. We found that the main types of technology used involved online information programs that provided strategies and support for informal carers. These are often run in combination with health professional support and counselling services. Such programs may require skilled health professionals to run them. Therefore, without skilled staff, these programs are not possible. However, such programs have the advantage of enabling a flexible support approach, which is important for a carer with time constraints. In particular, there was an increase in carer coping strategies related to the online programs. Although not tested, improved carer coping may reduce the likelihood of early entry of the person with young-onset dementia into nursing home care. This must be tested in future research as it may encourage more funding and research opportunities for technology development. In addition, these programs were rated good to very good by carers. However, online programs were at times limited by internet access and technical issues. Therefore, this must be taken into consideration, particularly where internet access can be challenged, such as in rural and remote communities where the internet signal might be weak. Furthermore, such programs limit health professionals’ access to carers’ non-verbal communication, sometimes making support difficult. However, these programs can be readily available in most communities and may be particularly useful when participants face similar challenges and are of similar ages ().

Most of the interventions did not have a long follow-up period apart from , who found that the benefits of a 4-week telephone-based psychological intervention had disappeared by six months. Future research must investigate the sustainability of the technology over a longer period so that effectiveness and dose requirements can be fully understood.

Young-onset dementia is known to have a significant impact on the marital relationship (). In a study of spousal carers, apathy was identified as hurting the marital relationship (). It was concluded that interventions targeting apathy could improve the marital relationship and delay the transition of the person with young-onset dementia to a nursing home. Unfortunately, none of the technology interventions targeted apathy in this review.

Several assistive technologies were involved in the review. The main message was that to be successful, the chosen assistive technology must be based on an analysis of the needs of the person with young-onset dementia and the carer. Technologies can fail when they are not targeted to the population or the condition.

It appears that technologies can support carers of people with young-onset dementia and should be introduced into care. However, as the number of studies and technologies were limited, further research is needed to determine the most effective technologies. Importantly, we must also understand the cost of technologies and their impact on care. While technologies may improve the quality of life for carers and people with young-onset dementia, this is likely not true for all technologies. None of the publications discussed the financial implications of the technologies, and yet the cost and availability of technologies are likely to impede their use. While some technologies are initially expensive, their overall effect may be cost-effective (). Incentives and regulations could assist carers in choosing cost-effective technologies.

Strengths and limitations

This review reports the technologies tested by informal carers of people with young-onset dementia to support care. It contributes to the body of knowledge regarding effective technologies to assist carers of young-onset dementia. Although only a few manuscripts were available, they allowed us to identify the technologies that can support carers of people with young-onset dementia. The review identified the main effective technologies as online information and skill-building programs.

There are some limitations to this review. The limited number of studies in this area resulted in us including various study designs with different levels of evidence. Although three RCTs were included, none of these studies were of a high standard. Furthermore, we may have missed some literature as we excluded literature in any language other than English and grey literature. This may have resulted in publication bias. Furthermore, as we only focused on informal carers of people with young-onset dementia, there may be other literature involving technologies that include other stakeholders, such as people with young-onset dementia and healthcare professionals. In addition, we have included papers where there are people with other forms of dementia in addition to young-onset dementia and where the population data was not specified in the analyses or results section of the paper. This may have skewed the findings about people with young-onset dementia.

Implications for future research and practice

Although many available technologies could assist informal carers, they may need help knowing where to find effective and reliable technologies (). Furthermore, the research on technologies, carers, and young-onset dementia is limited; therefore, it is impossible to know the available technologies’ efficacy unless experts thoroughly examine them. Therefore, there is a need for more research in this area and further development of technologies specific to the needs of this population of carers. Furthermore, future research requires the development of technologies that are co-designed for carers’ use. Once more technologies are available, they will need to be evaluated through robust study designs, such as RCTs, to assess the effectiveness of the technologies.

Another solution could be for a readily available list of available technologies, including their efficacy, cost and where they can be purchased. This may help carers avoid purchasing expensive or useless technologies. A dementia society could develop and maintain such a list. Helping carers of this population may help develop a more positive attitude, overcome the burden of care, and improve the quality of the carer-person with young-onset dementia relationship.

The manuscripts and data were from a few countries, and no data was from low-income countries, which we assume would differ from those found in these manuscripts as technologies tend to be more readily available in wealthier countries. It would be interesting to investigate if carers of people with young-onset dementia in low-income countries use technologies. If they are not being used, strategies to improve their use should be implemented.

Conclusions

Technologies can offer opportunities for carers to improve care for people with young-onset dementia. Researchers, dementia organizations and policymakers must assist carers by developing and evaluating technologies for this population and promoting evidence for their use.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Leanne Stockwell, Health Librarian, who assisted with the search terms.

Author contributions All authors designed the study. MS developed the search strategies and searched the databases. MS, LP, MQ, NL contributed to the article selection and data extraction. WM supervised the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors provided comments on and edited drafts of the manuscript. All authors agreed on the submission of the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Registration This review was registered in PROSPERO International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (Registration number: CRD42023478014).

References

- Arntzen C., Holthe T., Jentoft R. (2016). Tracing the successful incorporation of assistive technology into everyday life for younger people with dementia and family carers. Dementia, 15(4), 646–662. DOI: 10.1177/1471301214532263.

- Australian Strategic Policy Institute. (2024). Critical technology tracker: Two decades of data shows rewards of long-term research investment (downloaded 18 December 2024). https://www.aspi.org.au/opinion/critical-technology-tracker-two-decades-data-show-rewards-long-term-research-investment

- Binford S., Wallhagen M. I., Leutwyler H. (2023). Role identity transition: A conceptual framework for being the spouse of a person with early onset dementia. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 49(8), 27–34. DOI: 10.3928/00989134-20230707-03.

- Boots L. M. M., de Vugt M. E., Kempen G. I. K. M., Verhey F. R. J. (2018). Effectiveness of a blended care self-management program for caregivers of people with early-stage dementia (partner in balance): Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(7), Article e10017. DOI: 10.2196/10017.

- Bruinsma J., Peetoom K., Bakker C., Boots L., Millenaar J., Verhey F., de Vugt M. (2021). Tailoring and evaluating the web-based ‘Partner in Balance’ intervention for family caregivers of persons with young-onset dementia. Internet Interventions, 25(3), Article 100390. DOI: 10.1016/j.invent.2021.100390.

- Bruinsma J., Peetoom L., Boots L., Daemen M., Verhey F., Bakker C., de Vugt M. (2020). The quality of the relationship perceived by spouses of people with young-onset dementia. International Psychogeriatrics, 36(6), 1–10. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610220000332.

- Chirico I., Giebel C., Lion K., Mackowiak M., Chattat R., Cations M., Gabbay M., Moyle W., Pappadà A., Rymaszewska J., Senczyszyn A., Szczesniak D., Tetlow H., Trypka E., Valente M., Ottoboni G. (2022). Use of technology by people with dementia and informal carers during COVID-19: A cross-country comparison. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 37(9), 1–10. DOI: 10.1002/gps.5801.

- Climans R., Berall A., Santiago A. T., Gardner S., Margles D., Shnall A. (2022). Evaluation of virtual caregiver support groups for young-onset dementia family caregivers. Social Work with Groups, 46(2), 157–170. DOI: 10.1080/01609513.2022.2148038.

- Daemen M., Bruinsma J., Bakker C., Zwaaftink R. G., Koopmans R., Oostijen A., Loose B., Verhey F., de Vugt M., Peetoom K. (2022). A cross-sectional evaluation of the Dutch RHAPSODY program: Online information and support for caregivers of persons with young-onset dementia. Internet Interventions, 28(11), Article 100530. DOI: 10.1016/j.invent.2022.100530.

- de Stefano M., Esposito S., Iavarone A., Carpinelli Mazzi M., Siciliano M., Buonanno D., Atripaldi D., Trojsi F., Tedeschi G. (2022). Effects of phone-based psychological intervention on caregivers of patients with early-onset Alzheimer’s disease: A six-months study during the COVID-19 emergency in Italy. Brain Sciences, 12(3), 310. DOI: 10.3390/brainsci12030310.

- de Vugt M. E., Riedijk S. R., Aalten P., Tibben A., van Swieten J. C., Verhey F. R. (2006). Impact of behavioural problems on spousal caregivers: A comparison between Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 22(1), 35–41. DOI: 10.1159/000093102.

- Draper B., Withall A. (2016). Young onset dementia. International Medicine Journal, 46(7), 779–786. DOI: 10.1111/imj.13099.

- Fange A. M., Carlsson G., Chiatti C., Lethin C. (2020). Using sensor-based technology for safety and independence – the experience of people with dementia and their families. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 34(3), 648–657. DOI: 10.1111/scs.12766.

- Giebel C. (2022). Young-onset dementia and its difficulties in diagnosis and care. International Psychogeriatrics, 34(4), 315–317. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610220003452.

- Hasan H., Linger H. (2016). Enhancing the wellbeing of the elderly: Social use of digital technologies in aged care. Educational Gerontology, 42(11), 749–757. DOI: 10.1080/03601277.2016.1205425.

- Heintz H. L., Vahia I. V. (2020). Implementing adaptive technologies in dementia care: Local solutions for a global problem. International Psychogeriatrics, 32(8), 897–899. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610219001996.

- Hendriks S., Peetoom K., Bakker C., van der Flier W. M., Papma J. M., Koopmans R., Verhey F. R. J., de Vugt M., Köhler S., Withall A., Parlevliet J. L., Uysal-Bozkir Ö., Gibson R. C., Neita S. M., Nielsen T. R., Salem L. C., Nyberg J., Lopes M. A., Dominguez J. C.Young-Onset Dementia Epidemiology Study Group. (2021). Global prevalence of young-onset dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurology, 78(9), 1080–1090. DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2021.2161.

- Holdsworth K., McCabe M. (2018). The impact of younger-onset dementia on relationships, intimacy, and sexuality in midlife couples: A systematic review. International Psychogeriatrics, 30(1), 15–29. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610217001806.

- Holthe T., Jentoft R., Arntzen C., Thorsen K. (2018). Benefits and burdens: Family caregivers' experiences of assistive technology (AT) in everyday life with persons with young-onset dementia (YOD). Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 13(8), 754–762. DOI: 10.1080/17483107.2017.1373151.

- Hong Q. N., Pluye P., Fabregues S., Bartlett G., Boardman F., Cargo M., Dagenais P., Gagnon M.-P., Griffiths F., Nicolau B., O’Cathain A., Rousseau M.-C. (2018). The mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT) version 2018 user guide, department of family medicine. McGill University. https://mixedmethodsappraisaltoolpublic.pbworks.com/w/file/fetch/127916259/MMAT_2018_criteria-manual_2018-08-01_ENG.pdf

- Isidori V., Diamanti F., Gios L., Malfatti G., Perini F., Nicolini A., Longhini J., Forti S., Fraschini F., Bizzarri G., Brancorsini S., Gaudino A. (2022). Digital technologies and the role of health care professionals: Scoping review exploring nurses’ skills in the digital era and in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic. JMIR Nursing, 5(1), Article e37631. DOI: 10.2196/37631.

- Jentoft R., Holthe T., Arntzen C. (2014). The use of assistive technology in the everyday lives of young people living with dementia and their caregivers. Can a simple remote control make a difference? International Psychogeriatrics, 26(12), 2011–2021. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610214001069.

- Kerkhof Y. J. F., Bergsma A., Mangiaracina F., Planting C. H. M., Graff M. J. L., Dröes R. M. (2021). Are people with mild dementia able to (re)learn how to use technology? A literature review. International Psychogeriatrics, 34(2), 113–128. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610221000016.

- Kerkhof Y. J. F., Graff M. J. L., Bergsma A., de Vocht H. H. M., Dröes R.-M. (2016). Better self-management and meaningful activities thanks to tablets? Development of a person-centered program to support people with mild dementia and their carers through use of hand-held touch screen devices. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(11), 1917–1929. DOI: 10.1017/S1041610216001071.

- Lai M., Jeon Y.-H., McKenzie H., Withall A. (2023). Journey to diagnosis of young-onset dementia: A qualitative study of people with young-onset dementia and their family caregivers in Australia. Dementia, 22(5), 1097–1114. DOI: 10.1177/14713012231173013.

- Loi S., Cations M., Velakoulis D. (2023). Young-onset dementia diagnosis, management and care: A narrative review. Medical Journal of Australia, 218(4), 182–189. DOI: 10.5694/mja2.51849.

- Mengestie N. D., Yeneneh A., Baymot A. B., Kalayou M. H., Melaku M. S., Guadie H. A., Paulos G., Mewosha W. Z., Shimie A. W., Fentahun A., Wubante S. M., Tegegne M. D., Awol S. M. (2020). Health information technologies in a resource-limited setting: Knowledge, attitude and practice of health professionals. BioMed Research International, 2023(1), Article 4980391. DOI: 10.1155/2023/4980391.

- Mervin M. C., Moyle W., Jones C., Murfield J., Draper B., Beattie E., Shum D. H. K., O’Dwyer S., Thalib L. (2018). The cost-effectiveness of using PARO, a therapeutic robotic seal, to reduce agitation and medication use in dementia: Findings from a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 19(7), 619–622.e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.jamda.2017.10.008.

- Metcalfe A., Jones B., Mayer J., Gage H., Oyebode J., Boucault S., Aloui S., Schwertel U., Bohm M., Tezenas du Montcel S., Lebbah S., de Mendonca A., de Vugt M., Graff C., Jansen S., Hergueta T., Dubois B., Kurz A. (2019). Online information and support for carers of people with young-onset dementia: A multi-site randomised controlled pilot study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 34(10), 1455–1464. DOI: 10.1002/gps.5154.

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D. G.PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. British Medical Journal, 339(1), b2535. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.b2535.

- Moyle W. (2019). The promise of technology in the future of dementia care. Nature Reviews Neurology, 15(6), 353–359. DOI: 10.1038/s41582-019-0188-y.

- Moyle W., Pu L., Murfield J., Sung B., Sriram D., Liddle J., Estai M., Lion K.AACT Collaborative. (2022). Consumer and provider perspectives on technologies used within aged care: An Australian qualitative needs assessment survey. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(12), 2557–2565. DOI: 10.1177/07334648221120082.

- Myck-Wayne J., Ramirez S. (2014). Assistive technology and social skills. In Interdyscyplinarne Kontekst Pedagog Spec (5, pp. 95–106). Poland: Adam Mickiewicz University Press.

- O’Connell M. E., Crossley M., Cammer A., Morgan D., Allingham W., Cheavins B., Dalziel D., Lemire M., Mitchell S., Morgan E. (2014). Development and evaluation of a telehealth videoconferenced support group for rural spouses of individuals diagnosed with atypical early-onset dementias. Dementia, 13(3), 382–395. DOI: 10.1177/1471301212474143.

- Øksnebjerg L., Woods B., Ruth K., Lauridsen A., Kristiansen S., Holst H. D., Waldemar G. A. (2020). Tablet App supporting self-management for people with dementia: Explorative study of adoption and use patterns. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth, 17(1), Article e14694. DOI: 10.2196/14694.

- O’Shea E., Timmons S., O’Shea E., Irving K. (2019). Multiple stakeholders’ perspectives on respite service access for people with dementia and their carers. The Gerontologist, 59(5), e490–e500. DOI: 10.1093/geront/gnz095.

- Parkinson M., Carr S. M., Rushmer R., Abley C. (2016). Investigating what works to support family carers of people with dementia: A rapid realist review. Journal of Public Health, 39(4), 290–301. DOI: 10.1093/pubmed/fdw100.

- Perin S., Lai R., Diehl-Schmid J., You E., Kurz A., Tensil M., Wenz M., Foertsch B., Lautenschlager N. T. (2023). Online counselling for family carers of people with young onset dementia: The RHAPSODY-Plus pilot study. Digital Health, 9(1), Article 20552076231161962. DOI: 10.1177/20552076231161962.

- Persson A. C., Dahlberg L., Janeslatt G., Moller M., Lofgren M. (2023). Daily time management in dementia: Qualitative interviews with persons with dementia and their significant others. BMC Geriatrics, 23(1), 405. DOI: 10.1186/s12877-023-04032-8.

- Riikonen M., Mäkelä K., Perälä S. (2010). Safety and monitoring technologies for the homes of people with dementia. Gerontechnology, 9(1), 1569. DOI: 10.4017/gt.2010.09.01.003.00.

- Shnall A., Agate A., Grinberg A., Huijbregts M., Nguyen M., Chow T. W. (2013). Development of supportive services for frontotemporal dementias through community engagement. International Review of Psychiatry, 25(2), 246–252. DOI: 10.3109/09540261.2013.767780.

- Sokolovič L., Hofmann M. J., Mohammad N., Kukolja J. (2023). Neuropsychological differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia: A systematic review with meta-regressions. Frontiers Ageing in Neuroscience, 15(1), Article 1267434. DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2023.1267434.

- World Health Organisation. (2023). Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- Xiong C., Ye B., Mihailidis A., Cameron J. I., Astell A., Nalder E., Colantonio A. (2020). Sex and gender differences in technology needs and preferences among informal caregivers of persons with dementia. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 176. DOI: 10.1186/s12877-020-01548-1.