Introduction

Colorectal anastomotic leakage (CAL) is the most frequent major adverse event that occurs after a colorectal surgery. In spite of advances including double-stapling technique (DST) and other operative modalities, the incidence of anastomotic failure is approximately 10% [,,]. Recognized risk factors for CAL include older age and male gender, inadequacy of blood supply to the anastomosis, preoperative chemoradiotherapy, obesity, and emergency surgery []. Other technical factors associated with CAL include increased blood loss, anastomosis under tension, and stapler failure. Anastomotic complications have severe implications for immediate postoperative morbidity and mortality risk, as well as long-term, disease-free, and overall survival []. Therefore, reduction of CAL is crucial for good operative outcomes.

To prevent CAL, substantial efforts have been made. Among these, the air leak test (ALT) is reportedly the most frequently performed intraoperative test to identify a mechanically insufficient anastomosis []. A randomized prospective study of the intraoperative ALT showed significant reduction of postoperative leakage in the tested group []. Direct insufflation of air at the level of the anastomosis by intraoperative colonoscopy (IOCS) may be reliable for ensuring adequate intraluminal pressure to demonstrate a leak. The use of IOCS allows direct visualization and testing with the ALT for anastomotic defects [,].

The management of a laparoscopic intraoperative anastomotic air leak (IOAL) identified by the ALT is a matter of debate. Intraoperative repair of stapled anastomotic defects using interrupted sutures is the usual approach []. On the other hand, oversewing of the anastomosis at the site of leakage is reported to be associated with higher subsequent leakage compared with revision of the anastomosis or fecal diversion []. Thus, the approaches to an IOAL have not been fully investigated. The present study aimed to clarify the safe management of an IOAL in laparoscopic colorectal surgery.

Patients and Methods

Consecutive patients who underwent laparoscopic resection with DST anastomosis for left-sided colorectal cancer (CRC) during the study period from April 2015 to June 2016 were retrospectively reviewed. Patients with hand-sewn coloanal anastomosis and those who underwent a procedure without anastomosis, such as a Hartmann or Miles operation, were excluded. All patients underwent intraoperative flexible colonoscopic assessment of the anastomosis. After the completion of the anastomosis, the bowel was occluded proximally with an atraumatic intestinal clamp. The colonoscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted from the anus and the alignment of the staple line was inspected; an ALT was done by inflating air into the rectum with the colonoscope. An air test is then performed after irrigation of the pelvis with normal saline solution. Air leaks discovered during IOCS were repaired at the discretion of the operating surgeon. A repeat IOCS was then performed.

CAL was defined as leakage of bowel content from the anastomotic site. CAL was diagnosed when there was fecal discharge from the pelvic drain, or when fluid collection or fistula at the anastomotic site was detected radiologically in patients with symptoms, such as peritonitis []. Data of consecutive cases were collected by review of the clinical and operative record. All collected data were entered into a database and analyzed with JMP software version 9.0.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

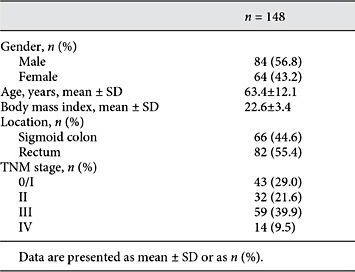

During the study period, 148 laparoscopic left-sided colorectal resections with DST anastomosis were performed in patients with CRC (Table 1). IOCS was safely performed in all cases without intraoperative complications. Intraoperative anastomotic ALT yielded positive results in 7 of 148 tested anastomoses (4.7%; Fig. 1), whereas 141 of 148 anastomoses (95.3%) were airtight (Table 2). A transanal drainage tube was inserted after the completion of the anastomosis in all 148 cases.

Fig. 1

Flowchart of enrolled patients (number of patients).

Among 7 cases with positive ALT, all but 1 (patient 7) were managed without converting to laparotomy. Reanastomosis was performed in all 7 patients, and diverting stomas were created for 2 patients. Three of the revised anastomoses showed air leakage on repeat ALT; additional interrupted suturing repair was performed in 2 of these, and they were finally confirmed to be airtight. One patient (patient 7) underwent reanastomosis 3 times because of anastomotic air leak; the procedure was finally converted to laparotomy, suturing repair was performed under direct vision, and a diverting stoma was created. One patient (patient 5) who had low anterior resection underwent revision with hand-sutured coloanal anastomosis and a diverting stoma.

Postoperative CAL occurred in 2 of 148 patients (1.4%), in whom the intraoperative ALT had been negative. Surgical site infections including wound infection and intraabdominal abscess were found in 7 (4.7%). Postoperative ileus, retrograde infection of the drainage tube, and other systemic complications, including pneumonia and urinary tract infection, developed in 1 (0.7%), 1 (0.7%), and 7 cases (4.7%), respectively. No 30-day postoperative mortality was observed. The average postoperative hospital stay was 13.5 days (range 7-44).

Among postoperative outcomes in patients with an IOAL identified using IOCS, 1 patient (patient 6) experienced retrograde infection of the drainage tube and was treated with antibiotics. No anastomotic leakage occurred in this group. The average postoperative hospital stay was 15 days (range 13-19).

Discussion

Various methods are employed to avoid CAL at each institution. ALT with IOCS is performed to detect mechanically insufficient colorectal anastomoses requiring intraoperative repair [,,].

The reported rates of IOAL range from 2.8 to 7.9%, which is similar to the rate seen our results (4.7%) [,,]. The postoperative incidence of CAL is reported to be around 10% []. In this study, CAL was noted in 2 patients (1.4%), and the incidence of CAL at our institute was revealed to be rather low. However, CAL and IOAL were noted in 9 patients (6.1%). If all patients with an IOAL had developed CAL, the rate of CAL in our study would be similar to that of other reports; therefore, the management of an IOAL was important to prevent clinical CAL.

When an intraoperative ALT is positive, solutions for the air leak range from simple suture closure of the defect and reconstruction of the anastomosis to repair of the defect or creation of a diverting stoma. Some reports recommended intraoperative repair of stapled anastomotic defects using interrupted sutures as a safe alternative to a diverting colostomy or ileostomy [,]. On the other hand, Ricciardi et al. [] suggested that suture repair alone in the setting of a positive air leak results in postoperative CAL because the postoperative clinical leak rate (12.2%) in their patients was significantly higher than the rate (3.8%) in anastomosis with initially negative intraoperative leak test results [].

In our study, IOCS detected air leak at the anastomosis in 7 cases (4.7%). Although DST revision of the anastomosis was performed in all but patient 5, 3 patients (50%) showed positive results at repeat ALT. On the basis of these results, it is assumed that IOAL due to technical factors, including stapler failure, twist in the bowel, or anastomosis under tension, might be repaired by DST revision of the anastomosis, IOAL due to patient factors, including poor nutrition, poor blood supply, and weakness of the bowel, could not be repaired by DST revision alone, and some additional solutions were needed to create an airtight reanastomosis site. In our results, 3 patients with a positive repeat ALT were successfully repaired by additional interrupted suture of the defects at the reanastomosis site. In 2 cases (patients 2 and 3), the point of repeat air leak was detected clearly using laparoscopy, and suturing repair was precisely performed at laparoscopic surgery by an experienced surgeon. We supposed that the technique of suture repair of an IOAL is important during laparoscopic operation, if DST is incomplete.

On the other hand, in patient 7, the repeat air leak and weakness of the anterior wall at the reanastomosis were detected laparoscopically in spite of DST revision of the anastomosis 3 times. Therefore, we converted to laparotomy, added suturing repair, and constructed a diverting stoma; postoperative CAL has not occurred in patient 7. In our study, a diverting stoma was constructed to protect the distal anastomosis in 2 cases whose reanastomosis sites were close to the anus.

As shown in Table 2, the rectal location may affect the method chosen to manage an IOAL. DST revision was performed in 6 patients with CRC of the sigmoid or recto-sigmoid; whereas, in patient 5 with CRC of the lower rectum, revision with hand-sutured coloanal anastomosis was performed because it was difficult to perform DST revision and direct suture repair of an IOAL in those who had undergone low anterior resection.

The limitation of this study is its retrospective nature, as it is based on medical record review. We tried to limit selection bias by collecting all consecutive patients during the study time period, but bias may exist owing to different experiences among the individual surgeons. Our study, conducted on 7 patients with positive results at intraoperative ALT, demonstrated a 0% incidence of CAL; we believe that combination management using DST revision, direct suturing repair, and a diverting stoma is useful and safe for intraoperative repair of anastomotic defects detected by IOCS.

In conclusion, IOCS seems feasible and useful for securing the anastomosis. Although large-scale multi-institutional analyses should be expected, the reported findings of this study suggest that the combination of DST revision, direct suture repair, and a diverting stoma could be recommended for the intraoperative repair of anastomotic defects detected by IOCS. In particular, the technique of suture repair of an IOAL assumes significant relevance during laparoscopic revision, if DST is incomplete.

Acknowledgment

This research is supported by the Project for Cancer Research and Therapeutic Evolution from the Japan Agency for Medical Research and development, AMED.

Ethics Statement

The study protocol was approved by the local ethics committees of the University of Tokyo (reference number: 3252-[3]) and written informed consent was obtained from all patients. All procedures in this study complied with the guidelines and principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Matsubara N, Miyata H, Gotoh M, Tomita N, Baba H, Kimura W, Nakagoe T, Simada M, Kitagawa Y, Sugihara K, Mori M: Mortality after common rectal surgery in Japan: a study on low anterior resection from a newly established nationwide large-scale clinical database. Dis Colon Rectum 2014;57:1075-1081.

- 2. Tanaka J, Nishikawa T, Tanaka T, Kiyomatsu T, Hata K, Kawai K, Kazama S, Nozawa H, Yamaguchi H, Ishihara S, Sunami E, Kitayama J, Watanabe T: Analysis of anastomotic leakage after rectal surgery: a case-control study. Ann Med Surg 2015;4:183-186.

- 3. Buchs NC, Gervaz P, Secic M, Bucher P, Mugnier-Konrad B, Morel P: Incidence, consequences, and risk factors for anastomotic dehiscence after colorectal surgery: a prospective monocentric study. Int J Colorectal Dis 2008;23:265-270.

- 4. Moran BJ: Predicting the risk and diminishing the consequences of anastomotic leakage after anterior resection for rectal cancer. Acta Chir Iugosl 2010;57:47-50.

- 5. Mirnezami A, Mirnezami R, Chandrakumaran K, Sasapu K, Sagar P, Finan P: Increased local recurrence and reduced survival from colorectal cancer following anastomotic leak: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg 2011;253:890-899.

- 6. Nachiappan S, Askari A, Currie A, Kennedy RH, Faiz O: Intraoperative assessment of colorectal anastomotic integrity: a systematic review. Surg Endosc 2014;28:2513-2530.

- 7. Beard JD, Nicholson ML, Sayers RD, Lloyd D, Everson NW: Intraoperative air testing of colorectal anastomoses: a prospective, randomized trial. Br J Surg 1990;77:1095-1097.

- 8. Ishihara S, Watanabe T, Nagawa H: Intraoperative colonoscopy for stapled anastomosis in colorectal surgery. Surg Today 2008;38:1063-1065.

- 9. Li VK, Wexner SD, Pulido N, Wang H, Jin HY, Weiss EG, Nogeuras JJ, Sands DR: Use of routine intraoperative endoscopy in elective laparoscopic colorectal surgery: can it further avoid anastomotic failure? Surg Endosc 2009;23:2459-2465.

- 10. Griffith CD, Hardcastle JD: Intraoperative testing of anastomotic integrity after stapled anterior resection for cancer. J R Coll Surg Edinb 1990;35:106-108.

- 11. Ricciardi R, Roberts PL, Marcello PW, Hall JF, Read TE, Schoetz DJ: Anastomotic leak testing after colorectal resection: what are the data? Arch Surg 2009;144:407-411; discussion 411-402.

- 12. Kamal T, Pai A, Velchuru VR, Zawadzki M, Park JJ, Marecik SJ, Abcarian H, Prasad LM: Should anastomotic assessment with flexible sigmoidoscopy be routine following laparoscopic restorative left colorectal resection? Colorectal Dis 2015;17:160-164.