Introduction

Often heralded as one of the most progressive steps taken by the British establishment in modern times of recognising the medical legitimacy of a previously illegal drug, in the UK, medical cannabis was approved as a medicine on November 1 2018. This was followed by the advent of medical cannabis as a National Institute for Health and Care Research (NICE) recommended treatment for two forms of severe intractable childhood-onset epilepsy in 2019. The restoration of cannabis into the medical discipline in the UK was spearheaded by the mothers of two severely ill children, Alfie Dingley and Billy Caldwell. The severe epilepsies both boys suffer were shown to be improved through medical cannabis, yet it proved a battle to receive this medicine. Their stories highlighted the plight of many other families in the UK in similar situations using medical cannabis to treat their children’s epilepsy. These families joined the charity End our Pain (founded by Peter Carroll and Will de Peyer in 2015) to campaign for access to the life-saving medication that their children require and to ensure that this is readily available to them through the National Health service (NHS).

Cannabis is a pharmacologically complex substance containing over 400 chemical entities and at least 144 cannabinoid compounds (). The two major cannabinoids that are investigated scientifically for medicinal use are d9-Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and Cannabidiol (CBD). THC is the primary psychoactive cannabinoid and is placed under Schedule 1 of the 1971 UN Convention on Psychotropic Substances (United Nations, 1971). CBD has never been a controlled drug in the UK and has no abuse potential (WHO, 2018). At the time of writing, cannabis based medicinal products (CBMPs) have been adopted for patient use in several US states and in over 20 countries but with varying policies and regulations and thus international consensus has not been achieved (). The current NICE recommendation for CBMPs for epilepsy is limited to CBD based medications as an adjunct to clobazam, i.e. Epidyolex (99.8% CBD, <0.3% THC) for two rare childhood-onset epilepsies (Lennox-Gastaut and Dravets syndrome) (NICE, 2019).

It has been estimated that there are around 112,000 young people (25 years and under) living with epilepsy in the UK today. 23,000 children under 18 suffer from intractable epilepsy for which no treatment works (Epilepsy Action, 2020). Since the change in law in 2018 lawful access to CBMPs has been overtly limited to licenced products such as Epidyolex which is only recommended when two anti-epileptic drugs (AEDs) have not adequately controlled seizures. Since the change in law, 185 prescriptions of Epidyolex were made available under the early access programme provided by the manufacturer and prescribed by specialist paediatric neurologists and 18 NHS prescriptions were made (Care Quality Commission, CQC, 2020). The CQC report found that less than 6% of prescriptions were made through the NHS so most families have to raise money to fund private assessments and prescriptions ().

Whilst for some patients, CBD only medications [such as Epidyolex] are effective in treating their epilepsy, others have reported only limited efficacy in symptom management as compared with full-spectrum unlicensed products which contain multiple components such as THC and other phytocannabinoids. However, this anecdotal evidence is yet to be reported in the scientific literature. A case series of ten children from the End our Pain cohort who were taking full-spectrum unlicensed CBMPs (Bedrolite and Bedica) showed an 80% mean reduction in monthly seizure frequency ().

Current regulations allow for doctors on the General Medical Councils (GMCs) specialist register to prescribe full-spectrum unlicensed products. However, there are several concerning barriers to accessing these medications which include physician uncertainty due to lack of clinical trial evidence, financial burdens on local NHS budgets and administrative hurdles in importing and dispensing scheduled drugs (please see ). The forensic examination of systemic flaws in the prescribing infrastructure for CBMPs for epilepsies can only be realised through the scientific assessment of evidence to which families with lived experience can contribute. With this information it will provide researchers, physicians, commissioners and legislators with an overview of how to streamline and improve the delivery of care for these patients.

Aims and approach

The aim of the current paper is to provide a qualitative assessment of the caregivers’ and patients’ experiences with their medical cannabis journeys. The importance of this is to provide deeper insights into conceptualising illness, health and dynamics of the medical profession (). The value of such an approach in our case is to provide robust scientific contributions to the clinico-political landscape within the field of scheduled drugs of medicinal value. This area has been the subject of a quadripartite war amongst medical scientists, clinical physicians, the political sphere and regulators. While some groups are trying hard to bring about real positive change for patients, others are still stifling progress. We aim to return the narrative to the patient. A recent meta-analysis of ten narrative medicine studies concludes on the overall usefulness as a tool in assessing patient illness and addressing patient needs but highlights the concerning paucity of this methodology despite its clear benefits (). This method has been utilised with increased popularity over the past 30 years (). Narrative medicine and evidence-based medicine have often been held in direct comparison due to the differences in methodological approaches; the former being interpreted as less rigorous and the latter more protocol based ().

As well as the importance of providing an insight into the mechanics of medical cannabis treatment in epilepsy we aim to provide indirect therapeutic value to patients and their families. Proponents of narrative medicine comment that it may enrich the clinical practice as it is can in some ways be a therapeutic process that helps restore autonomy to patients whose illness has taken that away (). Parental anxiety in childhood epilepsy has robustly been associated with poor outcomes for the children including lower quality of life and lower scores on adaptive behaviour domains (). Conversely the therapeutic () and physiological effects; including a reduction in hypertension through medical narrative story-telling (), provide a pathway whereby our study may have both tangible immediate effects on health outcomes of patients and caregivers as well as the intended impetus for legislative change to ease patient access.

Methodology

Narrative interviews

Despite its legalization in 2018, today most families in the UK are still lacking sustainable access to medical cannabis, which causes serious challenges in their day-to-day life. Our previous quantitative study () comprised an audit of the impact of medical cannabis of children with severe epilepsy, focusing on the physiological response to medical cannabis in the treatment of epilepsy.

For the present qualitative study, we used a narrative, open-ended approach to interview parents/carers. Of the 18 families originally approached, several were unable to participate due to time constraints and the commitments of looking after a severely ill child. 11 families were interviewed to understand their current situation in more depth, and to contextualise our quantitative findings, elucidating the challenges which still need to be addressed by policy-makers. The aim was to gain a detailed understanding of issues relevant to carers/patients in this under researched area. After the successful conduction of two pilot interviews, 9 further in-depth interviews were conducted.

Interviews commenced between May and July 2020 and generated over 12 hours of digital recordings. The topic guide (please see Annex A) was based on the current literature and designed to be open-ended to allow for participants’ narrative to emerge with limited researcher interference. Amongst other themes, the topic guide addressed patients’ medical cannabis journeys, perceived benefits and side effects of CBMPs, main barriers to prescriptions, and the impact of COVID-19 on the situation.

All interviews were recorded with participants’ consent and transcribed verbatim applying the general CAQDAS[3] transcription guidelines (Silver and Lewins, 2014).

Participants

Participant recruitment was through the charity End our Pain, and its spokesperson Hannah Deacon. Participants were initially approached through Hannah Deacon and asked whether they would be interested in contributing to a qualitative study about their experiences with medical cannabis. If participants agreed, they were introduced to the lead researcher, sent an email outlining the study details and asked to sign consent forms. Patients’ ages ranged from 2–48 years.

Data analysis

Data was analysed with the qualitative software Atlas/ti (). Familiarity with all transcripts was gained through reading and re-reading the texts. Transcripts were coded iteratively using a hierarchical structure where super-ordinate themes (“principle codes” or “code families”) such as “benefit medical cannabis” were coded with sub-themes (“thematic codes”) such as “better eating and digestion”. The basic unit of analysis was a single turn of a participant speaking. However, Atlas/ti does not require the researcher to pre-specify any particular length of analytic unit and at times, several short turns were coded as one. An unlimited number of codes could be attached simultaneously to any fragment of text hence individual text segments are frequently assigned various codes. It was ensured that codes were homogenised across participants. For the analysis, memos comprising a selection of the actual quotes were attached to each code to remind researchers of how a particular concept had been addressed by participants.

When interpreting the interview data, the entire episode was considered holistically as the whole is often more than the sum of its parts (). Moreover, questions that arose during the analytic procedure (such as about commonly occurring relations between discursive themes) were addressed by refining searches focused on particular codes.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Imperial College Research Ethics Committee (20IC5830 ICREC Committee 01/05/2020). When selecting and involving participants full information about the purposes and uses of participants’ contributions was provided. Participants were assured of their right to withdraw from the study at any time and offered access to the results of the research before submission for publication.

Results

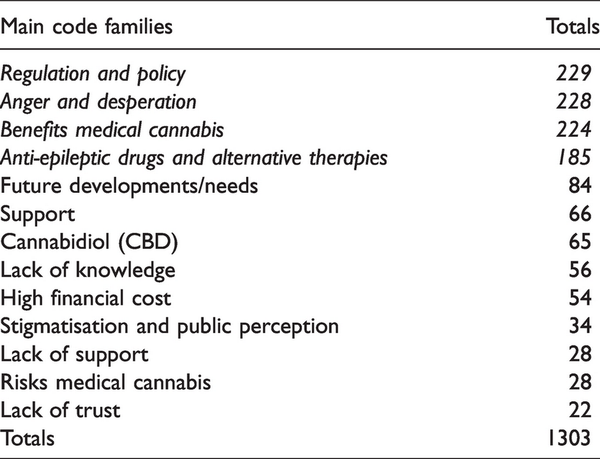

The following sections present an overview of our extensive results, highlighting the key issues and most salient perspectives. Due to the large number of initial codes, codes were organised into code families, for example the code group ‘lack of trust’ comprises the sub-codes ‘lack of trust in doctors’, ‘lack of trust in government’, and ‘lack of trust in the pharmaceutical industry’. For transparency, a complete outline of all codes and examples of their respective quotations can be found in Appendix A. Table 1 shows the code families in order of total frequency of occurrence.

Participants discuss a broad range of issues associated with medical cannabis, many of which are not about the scientific aspects of the medicine per se. The four most prevalent issues are concerned with regulation and policy surrounding medical cannabis, the anger and desperation related to these policies, followed by the benefits of medical cannabis, and discussions around Anti-Epileptic Drugs (AEDs). For purpose of brevity, the following sections summarise the overarching themes of these four main code families in detail, whilst less prevalent code families are combined within sections.

Regulation and policy

Issues related to the regulation and policy-making of medical cannabis in the UK are a major concern for families. Participants not only had to deal with the severe ill health of their child but simultaneously had to fight an ongoing battle of getting the medical cannabis required to treat their children: “It’s been a battle to get the medicine and it absolutely shouldn’t be”.

The battle to get the medicine is related to the current scheduling of medical cannabis as an unlicensed medicine and the challenges of prescribing this entails for clinicians. Even when clinicians were supportive and tried to prescribe, their efforts were regularly blocked by the hospital trust, making it almost impossible to receive an NHS prescription for medical cannabis. Only two of the current families are exceptions, having received NHS prescriptions.

The current guidelines (e.g. by the British Paediatric Neurology Association) were perceived as far too strict by parents, and as preventing doctors from prescribing, with parents stating that for many doctors, confusion remained about the guidelines, adding an unnecessary extra layer to the challenges of prescribing:

“They’ve said in the guidelines it states that I can't do it because the guidelines won’t let me but as I said for the shared care agreement with your GP it doesn’t state it has to be an NHS paediatric neurologist, it just states it has to be a paediatric neurologist on the specialist register. At the moment I’m still emailing back and forward saying they are wrong about the guidelines.”

Consequently, patients had to be treated privately, at huge personal financial costs. estimate the mean costs at £1800 per month. This put many families in desperate situations. In order to be able to afford their medicines, two families had to sell their homes. The stresses of both campaigning and fundraising were further exacerbated by the current COVID-19 crisis, which prevented face-to-face meetings, so that families had to rely on e.g. online raffles to fund their children’s medicines.

Unsurprisingly, families were extremely disappointed with the current regulations and policies, and their translation into actions. After the legalisation of medical cannabis on November 1st 2018, all had assumed that it would now be available to treat their children: “I thought gosh any day now, I'm just going to get my NHS description, too. And of course, at every avenue, we've got turned down …” That this assumption turned out to be wrong, led to anger and resentment towards regulators and policy-makers, and the urgent request for wider access remains.

When parents were offered a CBMP option, this usually was Epidyolex, a CBD only isolate, which many found not suitable to treat their children’s condition/s, as it did not effectively control their seizures: “He still had seizures at night with Epidyolex”. Parents/carers highlighted the need for full spectrum products, and the importance of making a wider variety of medical cannabis products available, as is the case in other countries, such as Germany and the Netherlands. All agreed that swapping from a medicine which is working for their child to a medicine which may or may not work for them, was a risk they were unwilling to take.

At the time of writing, due to importation issues from Holland, two families had to swap from their trusted Bedrocan products to another CBMPs, which had a negative impact on the seizure frequency of their children (details in a forthcoming publication).

Regulations made it so challenging and costly to acquire their CBMPs that families often went to the Netherlands for help. Whilst some families were able to live in the country (at least short term), as a last resort, others brought the medicine back to the UK with them, aware of the considerable legal risk this entailed. This further added to the financial as well as psychological burden for families. Moreover, one family who travelled to the Netherlands was refused treatment there as “the doctor didn’t want to continue prescribing for all these English children”.

Anger and desperation

The lack of success as a result of the changed regulations led to anger and resentment amongst families: “It makes me so mad because they need to live a life in our shoes, you know, and then you know, I thought they won't come back and say you can't have it. You know when you find the medicine, it could alleviate some of that and it gets refused.”

Underlying their anger was the sheer desperation experienced by families, in that nothing else was working to treat their child’s often incontrollable epilepsy: “we knew we were coming to the end the drugs and the neurologist said to us at that point my truck is empty. There's nothing left to try.” All families had tried a broad variety and different combinations of various AEDs without sufficient success (and indeed, with major side effects), after which some families were asked to start a new cycle going through all medications again!

Often, anger and desperation were heightened through a challenging relationship with their doctor. Families felt frustrated and rejected: “It was a difficult relationship with her as I didn't feel listened to at the time and any kind of anxieties were always dismissed.” This dismissal and lack of understanding by doctors contributed to a lack of trust in the medical establishment: “They don't listen to parents and they are not interested. At least I felt that they didn't want to listen to anything I have to say.”

Lack of trust is shown to be a serious concern, and included lack of trust in the government, in doctors, and in the pharmaceutical industry. Lack of trust and the feeling of being lied to, might impede any information flow between government and the public, indicating the need for complete transparency and improved communications. Some parents expressed active distrust, not believing that doctors had their children’s best interest at heart: “They are supposed to have the best interests of the patients at heart and they do not, absolutely not- they've got the best interest of the pharmaceutical industry at heart- simple.”

Contributing to the challenging doctor patient relationship was the reversal of expertise, which was generally not welcomed by the medical establishment. On the one hand, there was a lack of knowledge by doctors, whilst on the other hand, parents had to become experts on how to treat their child’s condition with medical cannabis:

“In my experience, they don't like being told so- if there's a parent- I'll take myself as an example where I've done a lot of studying and I probably know cannabis better than they do and then you start sending them information and they're just like oh and some of them don't like that and it is kind of up the wrong way that it is parents telling them what to do.”

With experience came the realisation that most doctors still lack detailed knowledge about CBMPs, and that ‘cannabis’ remains stigmatised in medical circles: “When we got the discharge letter … she'd written “parents asking for THC compounds that are illegal to prescribe.”

Initial hopes and expectations that doctors know best evaporated- leading to parents becoming the experts on which drugs to use for their children, including their dosages and administrations. Much of parents’ knowledge was gained through social media/online research, as well as connection and communication with other affected families, who were providing much needed support. The support from other parents in similar situation proved invaluable. Parents used Whats app and additional media outlets to share information, the latest science, and other updates- essential as they often were dismissed by doctors, who lacked the first-hand knowledge of CBMPs.

Most families experienced strong levels of support from family and friends. But this was not always immediate. Rather, parents had to educate their friends and family about medical cannabis, as it still is still stigmatised substance. This was generally successful, although one individual lost friends over their use of medical cannabis: “I lost a couple of friends, a couple of friends didn't agree with me and told me to stick to the professionals.” This stigmatisation of medical cannabis highlights the urgent need for further education on medical cannabis for physicians and the public alike.

Whilst many families struggled with the lack of support from their physician, and also felt unsupported by government and policy-makers, some doctors were supportive but felt their hands were tied due to the strict guidelines at present. Individual doctors tried to help, but often were ostracised by colleagues, putting their own position at risk: “He was trying to support us with the cannabis but he was threatened with disciplinary from his supervisors and his trust.”

Medical cannabis use was always initiated by parents/carers and doctors’ reactions varied from a complete lack of support and the involvement of social services, to full support, to the setting up of meetings with their trust, and learning everything they could do.

Parents’ in-depth knowledge and understanding of their child’s condition and medical cannabis use is second to none. In contrast to media reports, all had full understanding that cannabis is not a miracle cure- but that it substantially improves the condition/s their child suffers. The decision to continue their medical cannabis journeys is also about quality of life, and about enabling their children to live their best life possible under the very challenging conditions:

“We've all had to come to some sort of understanding that our children might die young and we don't know what life looks like … we're not being irresponsible. We're not holding onto this hope that this is all going to magically go away. It is about giving us as a family and our child, the best possible time.”

Benefits and risks of medical cannabis

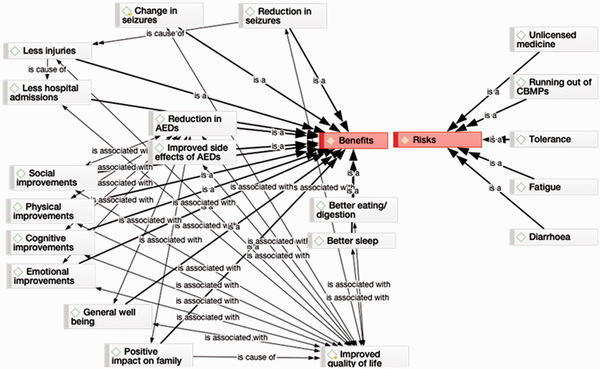

As indicated in Figure 1, the benefits of CBMPs for our families far outweigh the risks. Regarding risks, families mention that these are unlicensed medicines, with all the challenges this entails for prescribers, contributing to a risk for them to ‘run out of medicine’. In terms of physiological risk, for most (but not all) there was a build up of tolerance over time, which could largely be remedied by a change in product and dosing regime. One family mentioned tiredness as a result of CBMP use and attributed this to initially not knowing the correct dosing for their child: “it was trial and error”. This side effect disappeared with correct dosing.

Figure 1

Benefits vs. risks of medical cannabis.

A common side effect (mentioned by all families who had tried the product) was diarrhoea as a result of the use of Epidyolex. This side effect disappeared upon discontinuation of the product. With one notable exception, CBD by itself was not sufficiently helpful to the families, and seizures remained.

The benefits of medical cannabis go far wider than physiological benefits per se (please see for details on the physiological responses). Improvements were physical, cognitive, emotional as well as social, emphasising improvements in quality of life more generally, not only of the patient but also of their family. This is clearly important as children with chronic epilepsy experience significant impairments in physical, mental, and social domains of quality of life as reported by patients or parents ().

The reduction of seizures as well as often a change in the types of seizures had a major impact on the patient’s physical and cognitive development:

“Within three weeks of taking Bedroliteshe started to improve massively…basically her life was transformed. So she doesn't use the wheelchair… it wasn't a cure and it isn't a cure but she was able to go out. We were managing to drop one of the other drugs that she was on and her IQ came up massively.”

Whilst only few patients became completely seizure-free, the change of seizures, together with their reduced frequency is a substantial benefit: “He was having over a hundred seizures a day last year … so you have to remember that if he has four seizures and day and they're only like four, five seconds long, maybe up to 10 seconds long that’s a huge change.”

For other patients, night-time seizures stopped, which added huge value for parents/carers who had previously stayed up all night monitoring their child. For the first time in years, they were able to get a full night’s sleep- for some the first uninterrupted sleep they had since their child was born, which in turn immensely benefitted their own physical and mental health.

These improvements were also noted by doctors. Largely as a result of far less seizures, quality of life for these patients and their families improved immeasurably. Less seizures were associated with better sleep, better eating and digestion, more awareness and alertness, in addition to wide-ranging cognitive and physical improvements.

This contributed to a better quality of life not only for the patient but also for their whole family, who in many cases could enjoy time together for the first time in years: “it's better for us as a family because he's having less seizures. It means we can do more as a family and go out and you know, we're still conscious that you could have a seizure at any time. So we still follow him around all the time. But you know, it's better than it was- we can we just enjoy life.”

Additionally, several parents who previously had to leave their work to become full-time carers were able to return to work, which they described as a great benefit to themselves and their families.

Before using medical cannabis, the mental health of parents/carers, as well as siblings suffered badly as a result of having a severely sick child in the family, an issue still neglected by policy-makers, and excluded in their benefit and risk assessments. Many parents highlighted that at one stage, they clearly suffered from depression, anxiety and PTSD as a result of their child’s condition, often coupled with a lack of support:

“You find you lose yourself in the whole world your child's diagnosis, you know, because you're fighting for them to be well, that you are consumed by it, and then you just lose everything you do, you lose yourself. You know, when you lose your friends you just lose everything.”

One of the affected children was so terrified of again ending up in a wheelchair he had suspected PTSD and several siblings experienced severe anxiety disorders: ““He’s seen his little brother have horrific seizures all his life… a little toddler watching this mum and dad go off in an ambulance every week and being left with family and friends constantly or waking up in the morning and we're not here- it had a huge impact on his mental health.”

Hospital admissions and emergency medical treatment (which for several families were weekly occurrences before medical cannabis initiation) were reduced, and in many cases, stopped completely. For all, less frequent seizures also meant less physical injuries through these seizures: “he had a really bad drop seizure and banged his head and cut his head open and he had to have a CT scan under general anaesthetic.”

One family’s freedom of information act revealed the annual cost of hospital admissions and treatment of their child to have been in excess of £128,000 before CBMPs use (excluding their Epidyolex prescription), indicating the wider benefits associated with finding a medicine that works. Sadly, the costs of medical cannabis are still out of reach for many: “it's pretty unaffordable, especially on the high amounts so I couldn't afford to carry on Bedrolite at all.”

In sum, whilst the reduction in seizures is clearly the most notable benefit of medical cannabis treatment, it is intertwined with a broad variety of other positive outcomes that benefit not only the affected child, but also their family and society as a whole.

AEDs and alternative therapies

Although not specifically asked about AEDs during the interview, all families were keen to discuss other medications and alternative approaches they had tried prior to CBMPs initiation, often comparing them very negatively to the effects of medical cannabis.

Before using medical cannabis, in addition to the ketogenic diet and vagal nerve stimulation [an operative procedure where a simulator is implanted into the chest wall] in several instances, all families had tried a vast amount of AEDs to treat their children: “the amount of drugs he's been on… very very bad. We tried clobazam, lorazepam, Lamotrigine, IV Keppra, you know, phenobarbital, phenytoin, topiramate, sodium valproate, Zonisamide, steroids, oxoamide, chloral hydrate …to name a few!”

For most patients, the use of other AEDs was associated with severe side effects, for example on their child’s behaviour and cognition: “This was actually quite devastating to see a child so cognitively damaged and you know, it's the medication not the epilepsy.”

In addition to other benefits outlined above, families found that using CBMPs allowed them to reduce the number of other AEDs prescribed, and that their CBMPs also improved the often severe, side effects of various AEDs: “we feel that it reduces the side effects of drugs that he's on and it massively improved his quality of life.”

To sum up briefly, the above benefits contribute to important improvements in quality of life for the patient, as well as for their family. As highlighted by our parents, in the absence of a cure for their child’s condition/s, CBMPs offer the best quality of life possible for their child at present. These improvements in quality of life are in line with previous work, showing that caregivers report significant improvements in multiple related domains, including energy/fatigue, memory, other cognitive, control/helplessness, social interactions, and behaviour, as well as improvements in general quality of life scores (e.g. ). It is difficult to discern whether improved quality of life results primarily from direct medication effects, reduced seizures, reduction of AEDs or psychological benefits of reduced seizures, as each factor independently contributes to quality of life but may be causally interrelated ().

Discussion

Although NICE does not disallow the use of medical cannabis for refractory epilepsies, as there is still a lack of NHS prescriptions of CBMPs, current prescription costs are unsustainable for most families. In addition, the choice of CBMPs recommended by NICE is too limited for our families, many of whose children have not responded to these and yet have benefited from other products. It is essential that the change in law and with it positive recommendations for childhood epilepsy are now followed up by action that can help these families (and others like them) to access the CBMPs they need.

Whilst we agree that RCTs on medical cannabis and epilepsy are limited, findings highlight the need to also incorporate observational studies in decision-making about medical cannabis. Medical cannabis does not lend itself to traditional RCTs and an increasing alternative evidence base is building up. Various international databases, comprising 1000 s of patients are by now showing the emergence of patterns of evidence of efficacy ().

Whilst these databases, and observational studies such as can contribute to the evidence base for the efficacy of medical cannabis for the treatment of epilepsy, the current qualitative analysis contextualises these results, showing in detail what the reduction in (and change of) seizures mean for patients and their families, highlighting how these changes improve their quality of life.

Many of the issues raised in our study are not about the science of medical cannabis per se. Rather, they are political issues, related to the wider issue of trust and power in society, and the importance of expert versus lay opinions. This has wider implications than medical cannabis alone. The way that families are treated contrasts markedly with the way they want to be treated and emphasises the importance of including patients in decision-making about their medical plans and the value that should be given to their reported outcomes and wishes.

A holistic model of care, with more focus on compassionate and ethical treatment of patients and their families is essential. Access to CBMPs is one important aspect of this, together with more professional support, better communication with clinicians and policy makers who need to do more than pay lip service.

Limitations and implications for further research and policy making

As a qualitative study with a small sample size, we cannot claim broader representativeness or replicability of our findings to other disorders. Rather, our in-depth exploration of the reported experiences highlights the challenges of families with children with severe retractable epilepsies needing to access CBMPs in the UK in 2020. These experiences are woefully similar across all the families. By documenting their case studies, our narrative approach returned the voice back to patients and their families, so that these can be better understood, and their experiences used to contribute to the current evidence base on medical cannabis.

As the high financial costs are a recurring issue, future research should address not only the costs of CBMPs but equally, the cost savings that CBMPs can bring to the NHS, and society at large. A full health economics analysis could help to answer these vital questions. According to NICE national costing statement (2012) the annual estimated cost of epilepsy in the UK is £2 billion, and the report suggests up to 70% of the population could achieve seizure-freedom up from the current 52% if optimal treatment is provided. Given the reported superior clinical efficacy of CBMPs to mainstream AEDs () and a cost-saving strategy through legislative change we argue that given the current global climate, implementing CBMPs into mainstream medicine could also be an economically rational decision.

For this to happen, it is also important to further investigate the physician’s perspective and understand the reasons for their reluctance to prescribe in detail. ‘Cannabis’ remains a stigmatised medicine as the association with recreational cannabis and the risks of dependence and psychosis still loom large in people’s minds. This stigmatisation highlights the urgent need for further education on medical cannabis for physicians and the public alike. Many initiatives are now offering online education on medical cannabis (e.g. Drug Science; the Medical Cannabis Clinicians Society). To ensure that CBMPs can be accessed by all who could benefit from it, we need to further educate doctors as well as parents and foster an environment of trust and openness. Hopefully, the legalisation of medical cannabis in an ever-increasing number of countries globally can contribute to moving cannabis firmly in the direction of a medicine that can heal.

Concluding remarks

In December 2020, shortly before Christmas, the UK government announced that as a result of Britain leaving the European Union on December 31st 2020, the supply of Bedrocan products into the UK could no longer be secured, as UK prescriptions would no longer be valid in the Netherlands from where the products are imported.

After it looked like the families in this study (and others) would be let down once again by the UK government, Transvaal Apotheek (NL), together with Target Healthcare (UK) announced that they would work together to produce the exact same cannabis oil in the UK: “As health care providers we feel that it is our duty to continue the supply for this small group of patients who rely on our products. For these patients switching to other cannabis-based products can lead to serious adverse events.”

Unfortunately, unsustainable costs remain a barrier to access for most of these families, unless special licenses and NHS prescriptions can finally be provided. To ensure that the health of these patients and their families is not further compromised, a sustainable long-term solution is required. Our study highlighted the need for regulators and decision-makers to work together to prioritise the health of these vulnerable individuals and to help them access the medications they need to survive.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Hannah Deacon, for assisting with reaching out to our families and whose campaigning has enabled tangible change for many other individuals requiring CBMPs in the UK. We owe gratitude to all the families included in this study who took the time to be interviewed and openly and honestly shared their personal stories. We hope the current publication does your experiences justice.

Authors’ contributions AKS collected and analysed the data and developed the initial manuscript. RZ helped to transcribe and analyse the data and RZ and DJN contributed sections on medical cannabis and epilepsy. All authors reviewed and agreed to the final manuscript.

Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: AKS is Head of Research at Drug Science. DJN is Chair of Drug Science. RZ is Honorary Research Assistant at Drug Science. Drug Science receives an unrestricted educational grant from a consortium of medical cannabis companies. None of the companies had any role in study design, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report, or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Notes

1 https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ta615/chapter/3-Committee-discussion

2 Many of our families used CBMPs from the Dutch company Bedrocan. Bedrolite was often the preferred choice for families as its very low THC content (>1%) makes it non-intoxicating. For a complete explanation of Bedrocan products please see: https://bedrocan.com/products-services/

3 https://www.drugscience.org.uk/education/

4 https://www.ukmccs.org

5 https://www.transvaalapotheek.nl/cannabis-english/?fbclid=IwAR1dyxZ_zElH_6IK6-G4443OWcb40bhoiobVQAWAjWvwkeZ_AQCs7HNppkk

Supplemental material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- Care Quality Commission (CQC) Annual Update 2019 (2020) The safer management of controlled drugs. Available at: http://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/The_safer_management_of_controlled_drugs_Annual_update_2019.pdf (accessed 7 March 2021).

- Chafe R (2017) The value of qualitative description in health services and policy research. Healthcare Policy/Politiques de Sante 12(3): 12–18.

- Epilepsy Action (2020) https://www.epilepsy.org.uk (accessed 13 August 2021).

- Fioretti C, Mazzocco K, Riva S, et al. (2016) Research studies on patients’ illness experience using the narrative medicine approach: A systematic review. BMJ Open 6(7): e011220, pp 1–9.

- Gaskell G (2000) Individual and group interviewing. In: Bauer M, Gaskell G (eds) Qualitative Researching with Text, Image and Sound. London: Sage. pp. 45–65.

- Greenhalgh T (1999) Narrative based medicine: Narrative based medicine in an evidence based world. BMJ 318(7179): 323–325.

- Hanuš LO, Meyer SM, Muñoz E, et al. (2016) Phytocannabinoids: A unified critical inventory. Natural Product Reports 33(12): 1357–1392.

- Houston T, Cherrington A, Coley H, et al. (2011) The art and science of patient storytelling – Harnessing narrative communication for behavioral interventions: The ACCE project. Journal of Health Communication 16(7): 686–697.

- Jacoby A, Baker GA, Steen N, et al. (1996) The clinical course of epilepsy and its psychosocial correlates: Findings from a U.K. Community study. Epilepsia 37(2): 148–161.

- Jones C, Reilly C (2016) Parental anxiety in childhood epilepsy: A systematic review. Epilepsia 57(4): 529–537.

- Kleinman A (1989) The illness narratives: Suffering, healing, and the human condition. New York: Basic Books.

- Morris D (2008) Narrative medicines: Challenge and resistance. The Permanente Journal 12(1): 88–96.

- Muir T (1997) Atlas/ti the Knowledge Workbench: Visual Qualitative Data, Analysis, Management, Model Building: Short User’s Manual. Berlin: Scientific Software Development.

- NICE (2019) NICE Guideline [NG 144] Cannabis-based medicinal products. Published November 11th 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng144 (accessed 13 August 2021).

- Nutt D, Bazire S, Phillips LD, et al. (2020) So near yet so far: Why won’t the UK prescribe medical cannabis? BMJ Open 10(9): e038687.

- Porter BE, Jacobson C (2013) Report of a parent survey of cannabidiol-enriched cannabis use in pediatric treatment-resistant epilepsy. Epilepsy & Behavior 29(3): 574–577.

- Sabaz M, Cairns DR, Lawson JA, et al. (2001) The health-related quality of life of children with refractory epilepsy: A comparison of those with and without intellectual disability. Epilepsia 42(5): 621–628.

- Schlag AK, Baldwin DS, Barnes M, et al. (2020) Medical cannabis in the UK: From principle to practice. Journal of Psychopharmacology 34(9): 931–937.

- Silver C and Lewins A (2014) Using Software in Qualitative Research: A Step-by-Step Guide. London: Sage Research Methods.

- United Nations (UN) Convention on Psychotropic Substances (1971) https://www.unodc.org/pdf/convention_1971_en.pdf (accessed 13 August 2021).

- World Health Organisation (WHO) (2018) Cannabidiol (CBD): Critical Review Report. Expert Committee on Drug Dependence. 40th Meeting, Geneva 4–7 June 2018. https://www.who.int/medicines/access/controlled-substances/CannabidiolCriticalReview.pdf (accessed 13 August 2021).

- Zafar R, Schlag AK, Nutt D (2020) Ending the pain of children with severe epilepsy? An audit of the impact of medical cannabis in ten patients. Drug Science Policy and Law 6: 1–6.