Introduction

Managing diabetes related foot ulcers presents a significant challenge, contributing to high morbidity and healthcare costs. Approximately 15–25% of individuals with diabetes are expected to develop a foot ulcer during their lifetime. Additionally, the financial burden of treating DFUs is substantial, with annual management costs in the U.S estimated between $9 billion and $13 billion, on top of the existing costs of diabetes care. These persistent wounds are often difficult to treat and can lead to serious complications such as infections, amputations, and extended hospitalizations. Ensuring effective management of DFUs is crucial for improving patient outcomes, enhancing patients’ quality of life, and alleviating the financial strain on healthcare systems.

Despite the availability of various medical and surgical interventions aimed at promoting wound healing and preventing complications, the incidence of chronic non-healing wounds and associated morbidities remains high. Recently, the introduction of new therapeutic agents, particularly glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists like semaglutide, has shown potential in improving wound healing and reducing complications related to DFUs., Nevertheless, there is a lack of extensive, real-world data comparing the effectiveness of semaglutide to that of other commonly used anti-diabetes drugs like metformin in this patient group. This study seeks to fill this knowledge gap by examining the association between semaglutide use and wound healing outcomes in patients with DFUs, utilizing the comprehensive patient data from the TriNetX United States Research Network (live.trinetx.com). Incorporating semaglutide as an adjunctive therapy for diabetes related foot ulcer treatment could transform clinical practice. The current standard treatments for diabetes-related foot ulcers—debridement, infection control, offloading, and advanced wound dressings—often yield suboptimal healing rates, leading to prolonged patient suffering and higher healthcare costs. Adding semaglutide to the treatment regimen could improve the effectiveness of these conventional approaches, resulting in quicker healing times and better overall outcomes for patients. Additionally, the systemic benefits of semaglutide, such as weight loss and cardiovascular protection, provide additional advantages by addressing the multifaceted complications associated with diabetes. This holistic approach could enhance the quality of life for people living with diabetes, reducing the burden of chronic wounds and their associated complications. Semaglutide not only targets the wound itself but also addresses underlying issues that exacerbate wound healing problems in patients living with diabetes.

The objectives of this study are twofold: (1) to evaluate the extent to which semaglutide use is associated with a reduced risk of complications and (2) to compare these associations between patients using semaglutide and those who are not. Given the observational nature of this study, we aim to describe associations between semaglutide use and diabetes-related foot ulcer outcomes rather than establish causality. We hypothesized that semaglutide use would be associated with improved healing outcomes and a reduced risk of complications compared to patients who did not use semaglutide.

Methods

Data source

A retrospective cohort analysis was conducted using the TriNetX Research Network to identify patients who had been prescribed semaglutide in the last year. As of June 14, 2024, the TriNetX United States (US) Collaborative Network consists of 113.5 million patients across 64 healthcare organizations (HCOs). TriNetX provides access to de-identified patient data extracted from electronic medical records (EMRS), encompassing inpatient and outpatient visits. Consequently, our study was granted a letter of waiver by our institution’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) because it does not fall under the category of human subject research.

Study population

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study population consisted of patients with diabetes related foot ulcers and type 2 diabetes. Patients were selected based on the following inclusion criteria: (1) diagnosed with foot ulcers (ICD-10 codes: L97, L97.5, L97.50); (2) diagnosed with type 2 diabetes (ICD-10: E11); and (3) prescribed at least one prescription for semaglutide (RxNorm:1991302). Since no single ICD-10 code exists to explicitly combine DFUs with type 2 diabetes, these separate codes were used as proxies to identify relevant cases. Although this methodology may not capture the full spectrum of clinical presentations associated with DFUs, it provides a reasonable approximation of the study population based on available coding standards., The exclusion criteria were applied to remove patients with conditions that could affect wound healing: peripheral vascular disease (ICD-10: I73, I73.9), chronic kidney disease (ICD-10: N18), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (ICD-10: J44, J44.9), heart disease (ICD-10: I51, I51.9).

The exclusion criteria were selected to minimize confounding conditions with well-documented, direct impacts on wound healing in patients with diabetes related foot ulcers. Specifically, we excluded patients with peripheral vascular disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and heart disease are particularly relevant in diabetes related populations, as these conditions significantly impair blood flow, oxygenation, and cellular repair mechanisms critical for wound healing.– Given the prevalence of these conditions in diabetes patients and their pronounced effects on wound healing, these exclusion criteria were prioritized to create a more homogeneous study population and to reduce potential confounding from conditions that directly interfere with the study’s primary outcomes. While other immunosuppressive conditions may also influence healing, the selected exclusions represent those most immediately relevant to the diabetes related foot ulcer population. This targeted approach was chosen to reduce potential confounding from conditions that directly interfere with the study’s primary outcomes. As a result of selecting those with less severe microvascular complications, the findings may not be generalizable to patients with more complex DFUs, such as ischemic or non-neuropathic ulcers. In sum, this targeted approach was intended to focus on the association between semaglutide use and outcomes within a more homogeneous population with manageable ulcer characteristics, but it inherently narrows the scope of the analysis.

Cohorts and variables

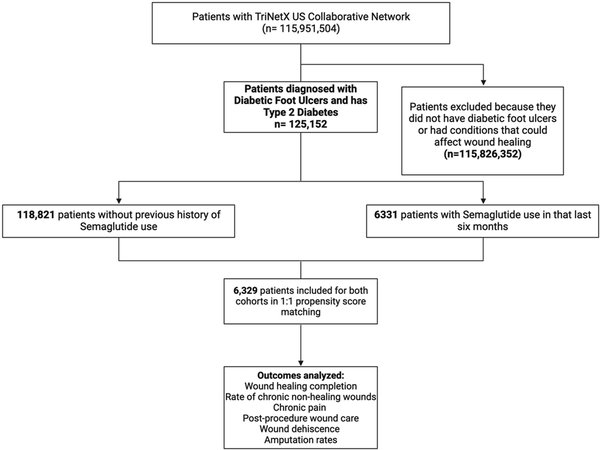

Figure 1 outlines the process of our study, which aimed to assess the risk of non-healing complications for diabetes related foot ulcer patients who had a Semaglutide prescription within 6 months prior to developing their ulcer (Cohort A) compared to those who had no Semaglutide prescription during that period (Cohort B). Both cohorts were assessed at the time of index of their diabetes related foot ulcer. The study investigated six outcomes related to wound healing: wound healing complications (ICD-10 codes: T79.8, T79.8XXA, T79.8XXD, T79.8XXS), rate of chronic non-healing wounds (ICD-10 code: T81.89XA), level of chronic pain (ICD-10 codes: G89.2, G89.28), incidence of post-procedural wound care (ICD-10 codes: Z48, Z48.02, Z48.03, Z48.01, Z48.00), occurrence of wound dehiscence (ICD-10 code: T81.3), and rates of amputation (ICD-10 codes: S98.332A, Z89.43). The inclusion of these outcomes were chosen based on previous research involving diabetes related foot ulcer patients, highlighting their impact on wound healing.,–

Figure 1

Flowchart diagram of selection process for our study.

Cumulative outcomes collection

The cumulative prevalence of outcomes was calculated by aggregating events related to diabetes related foot ulcers over the designated follow-up period, specifically from the time of the index DFU diagnosis. The increase in prevalence from Year 1 to Year 5 can be translated to a growing burden on health systems who are treating patients with diabetes related foot ulcers.

Outcomes definitions and coding approach

The outcomes in this study were identified using ICD-10 codes available in the TriNetX database. Definitions of outcomes and limitations of using ICD-10 to select clinical conditions are described below:

• Time to Complete Wound Healing: The codes T79.8, T79.8XXA, T79.8XXD, and T79.8XXS were used as indicators of complications related to wound healing. Although not exclusive to diabetes related foot ulcers, they were chosen as reasonable proxies to capture delayed wound healing.

• Chronic Non-Healing Wounds: The code T81.89XA was used to represent chronic non-healing wounds. This code encompasses a range of complications and was selected as a general marker of non-healing, acknowledging that it may include broader wound complications.

• Amputation: The codes S98.332A and Z89.43 were utilized to capture amputation events. While S98.332A includes traumatic amputations, it was the closest available code to represent DFU-related amputations in the dataset. This was chosen as a surrogate for amputation due to DFU complications.

• Wound Dehiscence: The code T81.3 was used to capture wound disruption, despite it being associated more frequently with surgical wounds healed by primary intention. It was chosen to approximate wound dehiscence in the context of DFUs.

Due to the de-identified nature of the TriNetX dataset, individual chart reviews to validate these codes against clinical notes were not feasible. Therefore, these ICD-10 codes serve as proxy measures for the outcomes of interest. We recognize that this coding approach may introduce some variability and have clarified this limitation in the manuscript.

Propensity score matching

Propensity score matching (PSM) was conducted using a 1:1 nearest neighbor matching algorithm without replacement, focusing on demographic variables of age, gender, race, and ethnicity to create comparable cohorts. This matching approach was performed using the TriNetX platform, which applies automated algorithms to ensure balanced matching. We selected age, gender, race, and ethnicity as matching variables due to their consistent coding across the dataset and their well-established influence on health outcomes and disparities, particularly in diabetes related foot ulcer (DFU) healing. Additional clinical variables such as chronic kidney disease that could confound healing outcomes were also excluded to create a more homogeneous cohort.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using TriNetX software (TRINETX, LLC, Cambridge, MA), which utilizes JAVA, R, and Python programming languages. For outcome analysis, we used chi-square tests to compare categorical variables and t-tests or Mann-Whitney U tests for continuous variables. Statistical significance was determined using TriNetX’s criteria (p < .05) without adjustments for multiple comparisons.

Results

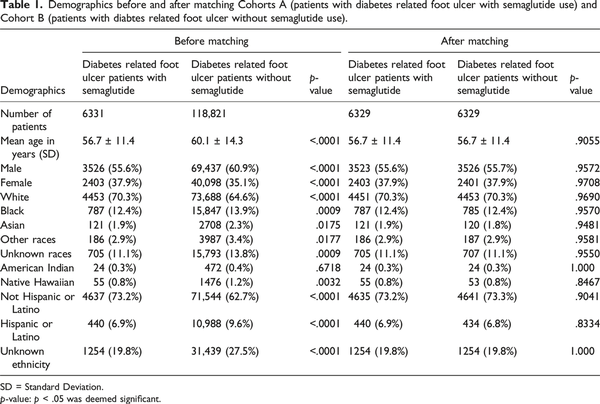

There were 118,821 DFU patients without a semaglutide prescription, with a mean age of 60.1 ± 14.3 years. A total of 6331 patients had received a Semaglutide prescription within 6 months prior to developing diabetes related foot ulcers, with a mean age of 56.7 ± 11.4 years. We matched a group of non-semaglutide users with the semaglutide users by age, gender, race, and ethnicity. After matching, both cohorts consisted of 6329 patients each. Demographic details for each cohort after matching are provided in Table 1.

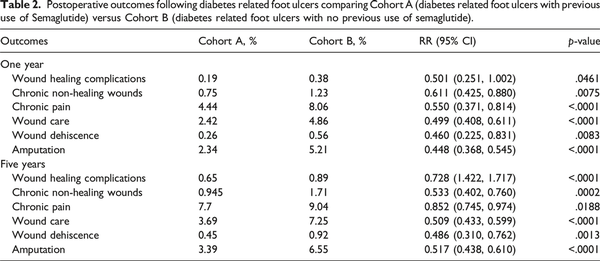

Patients with a prior history of diabetes related foot ulcer and previous use of semaglutide were compared to those who only had a prior history of diabetes related foot ulcers and without semaglutide. Our study revealed a greater association of significantly lower risk for wound healing complications, chronic non-healing wounds, chronic pain, wound care, wound dehiscence, and amputation following diabetes related foot ulcers in the semaglutide group for 1-year and 5-years after their foot ulcer compared to patients without a semaglutide prescription (Table 2).

At 1 year, semaglutide users were associated with a lower risks of wound healing complications (0.19% vs 0.38%, p = .0461), chronic non-healing wounds (0.75% vs 1.23%, p = .0075), chronic pain (4.44% vs 8.06%, p < .0001), wound care (2.42% vs 4.86%, p < .0001), wound dehiscence (0.26% vs 0.56%, p = .0083), and amputation (2.34% vs 5.21%, p < .0001) compared to non-users. At 5 years, semaglutide users continued to show a lower associated risks of wound healing complications (0.65% vs 0.89%, p < .0001), chronic non-healing wounds (0.94% vs 1.71%, p = .0002), chronic pain (7.71% vs 9.04%, p = .0188), wound care (3.69% vs 7.25%, p < .0001), wound dehiscence (0.45% vs 0.92%, p = .0013), and amputation (3.39% vs 6.55%, p < .0001).

Discussion

While the findings suggest a significant association between semaglutide use and improved diabetes related foot ulcer outcomes, it is important to recognize that this association does not imply causation. The improved outcomes observed in semaglutide users may reflect better overall diabetes management, rather than a direct effect of the medication itself. Thus, semaglutide could act as a marker of high-quality diabetes care, which may include comprehensive management of diabetes related foot ulcers. The results may be subject to residual confounding, as patients who receive semaglutide might be those who have better access to healthcare resources or receive more comprehensive diabetes management, including optimal diabetes related foot ulcer care.

Diabetes related foot ulcers represent a formidable challenge in healthcare due to their propensity for severe complications such as chronic non-healing wounds, chronic pain, wound care, wound dehiscence, and amputation. These complications not only significantly impact patients’ quality of life but also impose a substantial burden on healthcare systems., This study provides strong evidence that semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, is associated with enhance healing of diabetes related ulcers. Our findings revealed that patients with a history of semaglutide use were associated with significantly lower risk of adverse outcomes such as wound dehiscence and amputation. These results align with existing research highlighting the benefits of GLP-1 agonists in skin healing and systemic diabetes management.8 Given the high incidence of non-healing wounds among patients living with diabetes, which can lead to severe complications like infections, chronic pain, and amputations, the role of semaglutide in promoting wound healing is especially crucial. Our study provides evidence on the potential benefit of semaglutide in managing diabetes and enhancing wound healing outcomes, filling a crucial gap in the existing literature.

Existing literature on diabetes related foot ulcers often reports varying success rates in wound healing and complications, reflecting the complexity of managing this condition., In contrast, our study demonstrated consistent advantages for semaglutide users across multiple outcome measures, providing robust real-world evidence supporting its potential role in clinical practice. These findings contribute valuable insights into the effectiveness of semaglutide in improving diabetes related foot ulcer management, complementing and reinforcing previous research efforts. The long-term management of diabetes related foot ulcers poses significant challenges due to the risk of recurrence and persistent complications. By extending our follow-up period to 5 years, our study provided valuable insights into the ongoing associations between semaglutide use and outcomes, including reduced risks of chronic pain and amputation. These findings shed light on the potential of semaglutide to mitigate the chronic sequelae of diabetes-related foot ulcers, offering hope for improved long-term patient outcomes.

Mechanisms of action

The mechanisms by which semaglutide facilitates wound healing are complex and interconnected. One of the primary factors is semaglutide’s ability to improve glycemic control. Chronic hyperglycemia, common in individuals living with diabetes, hampers wound healing by reducing angiogenesis, increasing inflammation, and promoting the formation of advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) that can damage tissues. By effectively lowering blood glucose levels, semaglutide alleviates these harmful effects, creating a more conducive environment for wound repair.,

GLP-1 receptors are found in various tissues, including endothelial cells, which are essential for angiogenesis—the formation of new blood vessels. Semaglutide has been shown to stimulate endothelial cell proliferation and migration, crucial steps in angiogenesis. This process likely enhances oxygen and nutrient delivery to the wound site, promoting more efficient healing. Improved angiogenesis is particularly beneficial in diabetes related foot ulcers, where poor blood supply is a major obstacle to effective wound healing.

Moreover, semaglutide may have anti-inflammatory properties that are advantageous in treating chronic wounds. Chronic inflammation is a characteristic of diabetes related foot ulcers, often resulting in delayed healing. Activation of GLP-1 receptors has been linked to reduced expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and increased levels of anti-inflammatory mediators, creating a more favorable environment for wound repair. This anti-inflammatory effect is critical, as prolonged inflammation can cause tissue damage and further complicate the healing process.

Limitations and future research

Despite the encouraging findings, several limitations must be considered. Firstly, TriNetX does not provide patient-level data; instead, it includes encounter-level health records, pharmacy records, and insurance billing data, which are used to detect the presence or absence of specific medical, surgical, and prescription codes. This data is de-identified, restricting our ability to examine precise relationships between variables, such as weight loss and glycemic control (e.g., HbA1c levels) which are potentially influential in wound healing outcomes for patients on semaglutide. For instance, while previous studies have shown a lower risk of wound healing complications in patients living with diabetes using semaglutide, our study only indicates the presence of a diagnostic code without detailing pain levels. As an observational study, this analysis cannot establish causation between semaglutide use and diabetes related foot ulcer outcomes. The potential for residual confounding remains, as semaglutide prescription could be associated with higher standards of diabetes and foot ulcer care, rather than the medication directly improving outcomes. Future research should aim to control for these factors, possibly through randomized controlled trials, to more definitively establish the impact of semaglutide on diabetes related foot ulcer healing.

Another limitation is the lack of detailed information on the quantities of semaglutide prescribed versus those consumed by individual patients, as such data is unavailable. One important limitation of this study is the use of administrative codes to identify DFU cases and outcomes. Although the ICD-10 codes used (L97, L97.5, L97.50) are widely employed in research to identify DFU populations, they may not capture all relevant cases, particularly those with ischemic components. Additionally, we focused on foot amputations (ICD-10: Z89.4), which excludes major amputations above the foot, potentially underestimating the severity of some cases. The last limitation is the exclusion of patients with advanced vascular or cardiac comorbidities. While this reduces potential confounding, it also limits the generalizability of the results to a subset of patients with neuropathic ulcers and fewer complications. Thus, while the study suggests a potential association between semaglutide use and improved outcomes, it does not encompass the full spectrum of DFU presentations. Future studies are needed to explore these relationships in DFU populations at a severer level, including those with ischemic and mixed etiology ulcers.

Despite these limitations, the database provides evidence that supports the need for further investigation into patient-level data to better understand the relationships between semaglutide usage and wound healing outcomes. Larger, long-term studies are necessary to explore the potential efficacy and safety of semaglutide in diverse patient populations. Additionally, the specific pathways through which semaglutide may influence wound healing require further examination. A deeper understanding of these mechanisms could lead to the development of targeted therapies that enhance the wound healing potential of GLP-1 agonists. Future research should also consider the potential synergistic effects of semaglutide in combination with other wound healing modalities. For example, combining semaglutide with growth factors, stem cell therapy, or novel biomaterials could improve its therapeutic efficacy. Investigating these combinations in controlled clinical trials will be essential for optimizing treatment protocols. Furthermore, exploring the genetic and molecular mechanisms by which semaglutide impacts wound healing could pave the way for personalized medicine approaches in diabetes-related foot ulcer management.

Conclusion

Our study suggests an association between semaglutide use and favorable outcomes in patients with diabetes-related foot ulcers, including reductions in wound healing complications, chronic non-healing wounds, chronic pain, wound care needs, wound dehiscence, and amputation. These findings indicate that semaglutide may have potential as an adjunct in diabetes-related foot ulcer management, though further investigation is warranted to confirm its effects within clinical practice. Future research should focus on clarifying the underlying mechanisms and exploring possible synergistic treatment combinations to enhance protocol effectiveness for this complex and prevalent complication of diabetes.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Sarah T. Smith, PhD, for her assistance with editing the manuscript in preparation for submission. Additionally, we would like to thank Dr Norma Perez and the Center of Excellence for Professional Advancement and Research with their guidance and support. The authors would like to thank BioRender.com for creating Figure 1 for our manuscript.

Author contributions Joshua E. Lewis, BS: Conceptualization, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, and writing—review and editing, data curation. Diana K. Omenge, BS: Writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. Amani R. Patterson, MBS, BA: Writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. Ogechukwu Anwaegbu, BS: Writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. Nangah N. Tabukum, BS: Writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. Jimmie E. Lewis III, BS: Writing—original draft preparation and writing—review and editing. Wei-Chen Lee: Reviewing and editing, supervision, and conceptualization.

Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This project was funded in part by the Department of Health and Human Services, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), through its grant to the UTMB Center of Excellence for Professional Advancement and Research (grant number 1 D34HP49234‐01‐00). HRSA had no role in decisions related to the research, authorship, or publication of this article. This research was supported by the Institute for Translational Sciences at the University of Texas Medical Branch, supported in part by a Clinical and Translational Science Award (UL1 TR001439) from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

References

- 1. Doğruel H, Aydemir M, Balci MK. Management of diabetic foot ulcers and the challenging points: an endocrine view. World J Diabetes 2022; 13(1): 27–36. DOI: 10.4239/wjd.v13.i1.27.

- 2. Singh N, Armstrong DG, Lipsky BA. Preventing foot ulcers in patients with diabetes. JAMA 2005; 293(2): 217–228. DOI: 10.1001/jama.293.2.217.

- 3. Rice JB, Desai U, Cummings AKG, et al. Burden of diabetic foot ulcers for medicare and private insurers. Diabetes Care 2014; 37(3): 651–658. DOI: 10.2337/dc13-2176.

- 4. Baig MS, Banu A, Zehravi M, et al. An overview of diabetic foot ulcers and associated problems with special emphasis on treatments with antimicrobials. Life 2022; 12(7): 1054. DOI: 10.3390/life12071054.

- 5. Swaminathan N, Awuah WA, Bharadwaj HR, et al. Early intervention and care for diabetic foot ulcers in low and middle income countries: addressing challenges and exploring future strategies: a narrative review. Health Sci Rep 2024; 7(5): e2075. DOI: 10.1002/hsr2.2075.

- 6. Frykberg RG, Banks J. Challenges in the treatment of chronic wounds. Adv Wound Care 2015; 4(9): 560–582. DOI: 10.1089/wound.2015.0635.

- 7. Shami D, Sousou JM, Batarseh E, et al. The roles of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists and sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors in decreasing the occurrence of adverse cardiorenal events in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cureus 2023; 15(1): e33484. DOI: 10.7759/cureus.33484.

- 8. Xia W, Yu H, Wen P. Meta-analysis on GLP-1 mediated modulation of autophagy in islet β-cells: prospectus for improved wound healing in type 2 diabetes. Int Wound J 2024; 21(4): e14841. DOI: 10.1111/iwj.14841.

- 9. Brunton SA, Mosenzon O, Wright EE. Integrating oral semaglutide into clinical practice in primary care: for whom, when, and how? Postgrad Med J 2020; 132(sup2): 48–60. DOI: 10.1080/00325481.2020.1798162.

- 10. Everett E, Mathioudakis N. Update on management of diabetic foot ulcers. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2018; 1411(1): 153–165. DOI: 10.1111/nyas.13569.

- 11. Andersen A, Knop FK, Vilsbøll T. A pharmacological and clinical overview of oral semaglutide for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Drugs 2021; 81(9): 1003–1030. DOI: 10.1007/s40265-021-01499-w.

- 12. Ghusn W, De la Rosa A, Sacoto D, et al. Weight loss outcomes associated with semaglutide treatment for patients with overweight or obesity. JAMA Netw Open 2022; 5(9): e2231982. DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.31982.

- 13. Salazar JJ, Ennis WJ, Koh TJ. Diabetes medications: impact on inflammation and wound healing. J Diabet Complicat 2016; 30(4): 746–752. DOI: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2015.12.017.

- 14. 2025 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code E11.621: type 2 diabetes mellitus with foot ulcer. https://www.icd10data.com/ICD10CM/Codes/E00-E89/E08-E13/E11-/E11.621?utm_source=chatgpt.com (Accessed January 3, 2025).

- 15. CPMA JDL DPM, FASPS, MAPWCA, CPC. Diabetic foot ulcer coding - diabetes awareness month. Intellicure, November 3, 2021. https://www.intellicure.com/blog/diabetic-foot-ulcer-coding/ (Accessed 3 January 2025).

- 16. He Y, Zhu H, Xu W, et al. Wound healing rates in COPD patients undergoing traditional pulmonary rehabilitation versus tailored Wound‐Centric interventions. Int Wound J 2024; 21(4): e14863. DOI: 10.1111/iwj.14863.

- 17. Bonnet JB, Sultan A. Narrative review of the relationship between CKD and diabetic foot ulcer. Kidney Int Rep 2021; 7(3): 381–388. DOI: 10.1016/j.ekir.2021.12.018.

- 18. Soyoye DO, Abiodun OO, Ikem RT, et al. Diabetes and peripheral artery disease: a review. World J Diabetes 2021; 12(6): 827–838. DOI: 10.4239/wjd.v12.i6.827.

- 19. Mieczkowski M, Mrozikiewicz-Rakowska B, Kowara M, et al. The problem of wound healing in diabetes—from molecular pathways to the design of an animal model. Int J Mol Sci 2022; 23(14): 7930. DOI: 10.3390/ijms23147930.

- 20. Bhardwaj P, Zolper EG, Abadeer AI, et al. New and recurrent ulcerations after free tissue transfer with partial bony resection in chronic foot wounds within a comorbid population. Plast Reconstr Surg 2024; 153(1): 233–241. DOI: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000010564.

- 21. Armstrong DG, Fisher TK, Lepow B, et al. Pathophysiology and principles of management of the diabetic foot. In: Fitridge R, Thompson M (eds). Mechanisms of Vascular Disease: A Reference Book for Vascular Specialists. Adelaide: University of Adelaide Press, 2011. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534268/ (Accessed 4 July 2024).

- 22. Avishai E, Yeghiazaryan K, Golubnitschaja O. Impaired wound healing: facts and hypotheses for multi-professional considerations in predictive, preventive and personalised medicine. EPMA J 2017; 8(1): 23–33. DOI: 10.1007/s13167-017-0081-y.

- 23. Yang L, Rong GC, Wu QN. Diabetic foot ulcer: challenges and future. World J Diabetes 2022; 13(12): 1014–1034. DOI: 10.4239/wjd.v13.i12.1014.

- 24. Akkus G, Sert M. Diabetic foot ulcers: a devastating complication of diabetes mellitus continues non-stop in spite of new medical treatment modalities. World J Diabetes 2022; 13(12): 1106–1121. DOI: 10.4239/wjd.v13.i12.1106.

- 25. Tiwari A, Balasundaram P. Public health considerations regarding obesity. StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK572122/ (Accessed 6 July 2024).

- 26. Wang X, Yuan CX, Xu B, et al. Diabetic foot ulcers: classification, risk factors and management. World J Diabetes 2022; 13(12): 1049–1065. DOI: 10.4239/wjd.v13.i12.1049.

- 27. Semaglutide, a glucagon like peptide-1 receptor agonist with cardiovascular benefits for management of type 2 diabetes - PMC. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8736331/ (Accessed June 20, 2024).

- 28. Diabetic wound-healing science - PMC. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8539411/ (Accessed June 20, 2024).

- 29. Semaglutide - StatPearls - NCBI bookshelf. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK603723/ (Accessed June 30, 2024).

- 30. Aronis KN, Chamberland JP, Mantzoros CS. GLP-1 promotes angiogenesis in human endothelial cells in a dose-dependent manner, through the Akt, Src and PKC pathways. Metabolism 2013; 62(9): 1279–1286. DOI: 10.1016/j.metabol.2013.04.010.

- 31. Yue L, Chen S, Ren Q, et al. Effects of semaglutide on vascular structure and proteomics in high-fat diet-induced obese mice. Front Endocrinol 2022; 13: 995007. DOI: 10.3389/fendo.2022.995007.

- 32. Mehdi SF, Pusapati S, Anwar MS, et al. Glucagon-like peptide-1: a multi-faceted anti-inflammatory agent. Front Immunol 2023; 14: 1148209. DOI: 10.3389/fimmu.2023.1148209.