Introduction

According to data from the 2021 Global Burden of Disease Study, depressive disorders affect over 332 million individuals and are the second largest contributor of years lived with disability worldwide (GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators, ). From the spectrum perspective, subthreshold depression is a state between health and depressive disorders (Rodríguez et al., ). Individuals with subthreshold depression refer to those who have depressive symptoms but do not meet the diagnostic criteria (Rodríguez et al., ). A meta-analysis has shown that the prevalence of subthreshold depression is 11.0% inthe general population, and individuals with subthreshold depression have three times the risk of developing depressive disorders as those without (Zhang et al., ). Obviously, individuals with subthreshold depression are a high-risk group for depressive disorders, and identifying modifiable factors alleviating their depressive symptoms is crucial to preventing depressive disorders.

Lifestyles, such as physical activity, smoking, drinking, sleep and body mass index (BMI), are of great concern in disease prevention due to their modifiable nature (Wang et al., ). Lifestyles tend to coexist and are interrelated in the real world (Zhang et al., ), so exploring the association between combined lifestyle and depressive symptoms is advocated (Cao et al., ; Collins et al., ; Dabravolskaj et al., ; Wang et al., ; Werneck et al., ). A meta-analysis of observational studies has shown that adherence to an overall healthy lifestyle is associated with a lower risk of depressive symptoms (Wang et al., ). Since existing studies have been conducted in the general population (Cao et al., ; Collins et al., ; Dabravolskaj et al., ; Wang et al., ; Werneck et al., ), it remains unclear whether these findings can be generalized to individuals with subthreshold depression. Moreover, depressive symptoms are highly heterogeneous and are usually divided into somatic symptoms and cognitive-affective symptoms (Iob et al., ). Currently, only a few studies have evaluated the associations between a single lifestyle (i.e. physical activity and BMI) and subtypes of depressive symptoms in the general population, but have ignored combined lifestyle (Chu et al., ; Wu et al., ). Hence, it is necessary to conduct studies to explore the associations of combined lifestyle with depressive symptoms and their subtypes among individuals with subthreshold depression.

The possible biological mechanisms by which a healthy lifestyle prevents or alleviates depressive symptoms involve maintaining homeostasis of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and immune inflammation (Lopresti et al., ). Contrary to a healthy lifestyle, childhood trauma (CT) is a recognized risk factor for depressive symptoms (Humphreys et al., ), and the biological mechanisms might involve dysregulation of the HPA axis and immune inflammation (Iob et al., , ). These suggest that a healthy lifestyle might mitigate the CT-induced exacerbation of depressive symptoms. In addition, unlike lifestyle, CT cannot be changed once it occurs, and its adverse effects might persist over a lifetime. Therefore, if an overall healthy lifestyle can mitigate or offset the CT-induced exacerbation of depressive symptoms, it is of great significance for preventing depressive disorders among individuals with CT, particularly from a public health standpoint. However, previous studies have only explored the modifying role of a single lifestyle (e.g. physical activity, smoking, alcohol consumption, sleep and BMI) in the association between CT and depressive symptoms among the general population, and the results are mixed (Boisgontier et al., ; Jiang et al., ; Masuya et al., ; Ramirez and Milan, ; Rice et al., ; Rowland et al., ; Royer and Wharton, ; Zhang et al., ). To date, it remains unclear whether or to what extent adopting an overall healthy lifestyle can alleviate the CT-induced exacerbation of depressive symptoms, whether in individuals with subthreshold depression or in the general population.

Therefore, this longitudinal study aimed to explore the associations of combined lifestyle, and its interaction with CT, with depressive symptoms and their subtypes (i.e. cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms) among adults with subthreshold depression.

Methods

Study design and participants

Data were from the Subthreshold Depression Cohort (SDC), a sub-cohort of the Depression Cohort in China, which was previously described in detail (Zhang et al., ). Briefly, the SDC is an ongoing, dynamic and prospective cohort that was launched in 2019. Participants were recruited from 34 primary health care centres in Nanshan District, Shenzhen, China, who were between 18 and 65 years of age, had no past or current psychiatric disorders (e.g. depressive disorders, schizophrenia, social phobia, obsessive-compulsive disorders, generalized anxiety disorders and substance abuse disorders), and were not pregnant or breastfeeding. Participants filled in the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) (Spitzer et al., ), and those with a PHQ-9 score ≥ 5 would be diagnosed with depressive disorders by a specialized psychiatrist using the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition criteria) (Liao et al., ). Participants with a PHQ-9 score of ≥ 5 but not diagnosed with depressive disorders were determined to have subthreshold depression and were included in the SDC (Liao et al., ). Depressive symptoms were assessed using the PHQ-9 every 6 months during follow-up. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of School of Public Health, Sun Yat-sen University (L2017044). All participants filled in informed consent. All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013.

As of March 2023, the SDC had been followed for 3.5 years and a total of 2306 participants had participated in the follow-up of this longitudinal study. After excluding participants with missing data on CT (n = 0) or lifestyle (n = 6), and those without data on depressive symptoms during follow-up (n = 2), we included 2298 participants in the analysis (Figure S1 in the Supplementary).

Assessment of combined lifestyle

At baseline, lifestyle factors were investigated through the self-reported questionnaire. Referring to previous studies, we defined the following five healthy lifestyles: no current smoking (Jia et al., ), no current drinking (Tang et al., ), regular physical exercise (Liao et al., ), optimal sleep duration (7 to < 9 h) (Lloyd-Jones et al., ) and no obesity (BMI < 28 kg/m2) (Qie et al., ). Regular physical exercise was defined as exercising once a week for at least 30 min each time (Liao et al., ). BMI was calculated by dividing weight in kilograms by the square of height in meters. For each lifestyle, we assigned 1 point for a healthy level and 0 point for an unhealthy level. Healthy lifestyle scores were the sum of the points and ranged from 0 to 5, with a higher score indicating a healthier lifestyle. Since a few participants adopted 0, 1 or 5 healthy lifestyles and the lower (33.3%) and upper (66.7%) tertiles of healthy lifestyle scores are 3 and 4, respectively, combined lifestyle was categorized into unfavourable (0–2), intermediate (3), and favourable (4–5) lifestyles.

Assessment of CT

At baseline, the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire-Short Form (CTQ-SF) was used to investigate CT occurring before the age of 16 (Bernstein et al., ). The CTQ-SF has high reliability and validity among the Chinese population (Zhao et al., ). The CTQ-SF includes five dimensions (i.e. physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, physical neglect and emotional neglect). Each dimension includes five items and each item was rated on a 5-point Likert scale (‘never’ = 1; ‘rarely’ = 2; ‘sometimes’ = 3; ‘often’ = 4 and ‘very often’ = 5). Each dimension score ranges from 5 to 25. Based on the cut-off points suggested by Bernstein et al. (), we used the following cut-off points for the presence of each CT: physical abuse scores ≥ 10, emotional abuse scores ≥ 13, sexual abuse scores ≥ 8, physical neglect scores ≥ 10 and emotional neglect scores ≥ 15 (Huang et al., ; Xie et al., ). Participants experiencing one or more subtypes of trauma were considered to have CT (Xie et al., ). The CTQ-SF has a high reliability in this study (McDonald’s omega = 0.90).

Assessment of depressive symptoms

At baseline and follow-up, depressive symptoms were assessed using the PHQ-9 (Spitzer et al., ), with high reliability and validity among the Chinese population (Sun et al., ). The PHQ-9 includes nine items and each item is scored from 0 to 3 (‘not at all’ = 0; ‘several days’ = 1; ‘more than half the days’ = 2; and ‘nearly every day’ = 3). Cognitive-affective symptoms were evaluated with items 1, 2, 6, 7 and 9, and somatic symptoms were evaluated with items 3, 4, 5 and 8 (Liao et al., ; Vrany et al., ). Depressive, cognitive-affective and somatic symptom scores range from 0 to 27, from 0 to 15 and from 0 to 12, respectively. A higher score suggests more severe symptoms. McDonald’s omegas for depressive, cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms were 0.88, 0.83 and 0.76, respectively.

Assessment of covariates

At baseline, covariates were evaluated using the self-report questionnaire. Sociodemographic factors included age, sex (male or female), educational level (junior high school or below; senior high school; or college or above) (Wang et al., ), employment status (employed, unemployed. retired or others), marital status (married, unmarried or divorced/widowed) (Liao et al., ), and household income (<10 000 yuan/month; 10 000–19 999 yuan/month; or ≥ 20 000 yuan/month) (Shi et al., ). Chronic diseases included hypertension, diabetes, heart disease, stroke, thyroid disease and tumors. Since a few participants had more than two diseases, the number of chronic diseases was categorized into 0, 1 and ≥ 2.

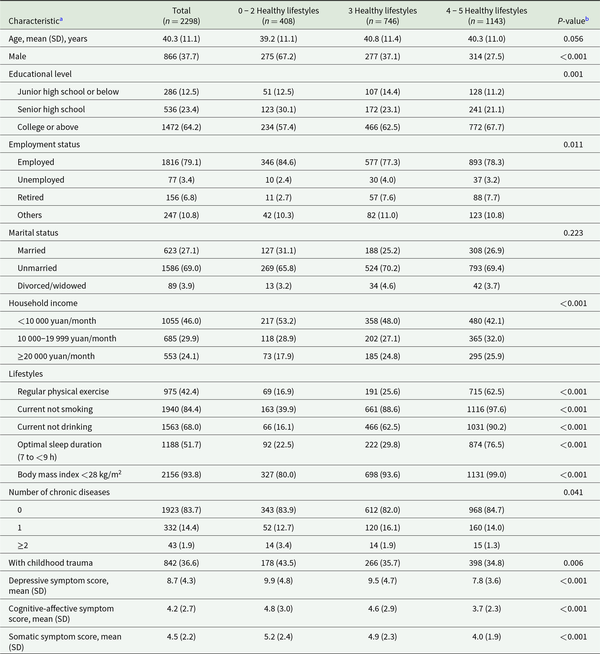

Statistical analyses

Baseline characteristics of patients were summarized across three lifestyle groups. Categorical variables were shown as frequency (percentage) and were compared using the Pearson Chi-squared tests or Fisher’s exact tests, as appropriate. Continuous variables were shown as mean (standard deviation [SD]) and were compared using the one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal-Wallis tests, as appropriate.

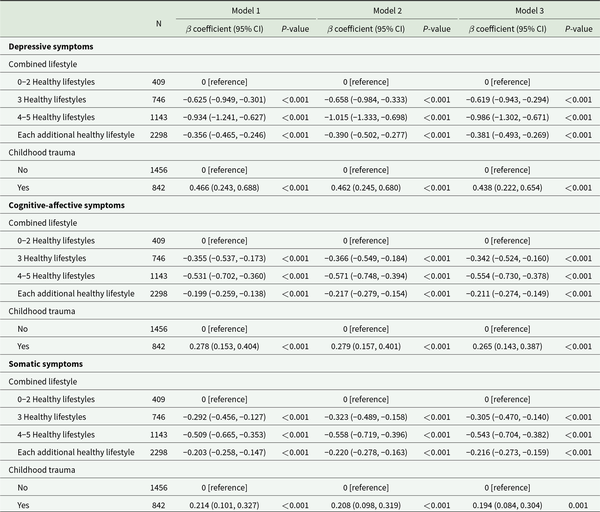

The missing proportions of all covariates were less than 0.3% (Table S1 in the Supplementary). To maximize the statistical power, we performed multiple imputations with chained equations with 10 data sets to impute covariates with missing values. Linear mixed models with random intercepts were used to estimate β coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) to explore the associations of combined lifestyle and CT with depressive symptoms during follow-up. Model 1 was adjusted for follow-up time (follow-up years from baseline) and baseline depressive symptoms (for depressive symptoms), cognitive-affective symptoms (for cognitive-affective symptoms) and somatic symptoms (for somatic symptoms). Model 2 was further adjusted for baseline factors including age, sex, educational level, employment status, marital status, household income and the number of chronic diseases. Model 3 was additionally adjusted for CT (for combined lifestyle) and combined lifestyle (for CT) at baseline. We repeated the above analysis process in the form of a continuous variable for combined lifestyle (each additional healthy lifestyle). Moreover, the dose–response associations of combined lifestyle with depressive symptoms were explored using the restricted cubic spline linked to linear mixed models, with three knots at the 10th, 50th and 90th percentiles of combined lifestyle.

The CTQ-SF measures the CT occurring before the age of 16, which is a relatively long time for elderly adults. Thus, the association between CT and depressive symptoms in young adults might be different from that in elderly adults, that is, age might modify the association between CT and depressive symptoms. We evaluated the interaction between age and CT by establishing a model that included CT, age, CT × age and covariates in model 3. The age-stratified analyses were further conducted if the interaction term (i.e. CT × age) was statistically significant.

To assess the interaction between combined lifestyle and CT, we established a model including combined lifestyle, CT, combined lifestyle × CT and covariates in model 3. Stratified analyses were further conducted if the interaction term (i.e. combined lifestyle × CT) was statistically significant.

To explore the joint associations, we classified participants into six groups according to combined lifestyle (0–2, 3 or 4–5 healthy lifestyles) and CT (yes or no) and estimated β coefficients and 95% CIs in different groups compared with those with 4–5 healthy lifestyles and without CT.

To verify the robustness of the results, we conducted three sensitivity analyses. First, we evaluated the association of weighted healthy lifestyle scores with depressive symptoms. Although the simple additive method of combined lifestyle had been used widely (Jin et al., ; Zhang et al., ), the underlying assumption is that the associations between different lifestyle factors and the outcome were identical, which might not be true. Therefore, we constructed weighted healthy lifestyle scores, where each lifestyle factor was weighted by its association with the outcome (i.e. β coefficients in Table S2 in the Supplementary). Participants were divided into three groups (i.e. unfavorable, intermediate and favorable) based on tertiles of weighted scores (Jia et al., ; Zhang et al., ). Second, we explored the association of combined lifestyle with depressive symptoms by sequentially excluding each lifestyle to identify lifestyles that might drive the association with depressive symptoms. The excluded lifestyle was used as a confounder. Finally, we performed all analyses in the main analysis after excluding participants with missing values for covariates to test the effect of missing values on the results.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 17.0 (StataCorp LLC). Statistical significance was defined as a two-tailed P-value < 0.05.

Results

Characteristics of participants

At the end of 3.5 years follow-up, the proportions of being diagnosed depressive disorders, keeping threshold depression and having no depressive symptoms (i.e. PHQ-9 score < 5) were 9.7%, 37.8% and 52.5%, respectively. Among the 2298 participants included in the analysis, the average age was 40.3 (SD, 11.1) years and 37.7% were male (Table 1). Compared with participants with 0–2 healthy lifestyles, those with 4–5 healthy lifestyles were more likely to be male and retired and were less likely to experience CT and have two or more chronic diseases. In addition, they have higher educational level, higher household income, and lower depressive, cognitive-affective, and somatic symptom scores. There was no statistically significant difference in baseline characteristics between total participants (n = 2306) and those included in analyses (n = 2298). (Table S3 in the Supplementary).

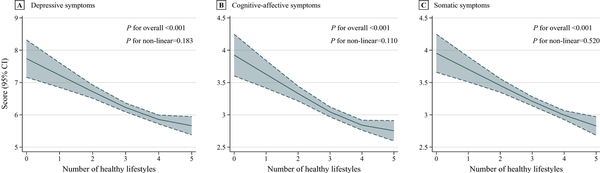

Individual association of combined lifestyle and CT with depressive symptoms

After adjusting for all covariates (Table 2, model 3), compared with 0–2 healthy lifestyles, 3 (β coefficient, −0.619 [95% CI, −0.943, −0.294]) and 4–5 (β coefficient, −0.986 [95% CI, −1.302, −0.671]) healthy lifestyles were associated with milder depressive symptoms during follow-up. Each additional healthy lifestyle was related to milder depressive symptoms during follow-up (β coefficient, −0.381 [95% CI, −0.493, −0.269]). The restricted cubic spline showed a negative linear dose–response association between combined lifestyle and depressive symptoms (Fig. 1a, P for overall < 0.001 and P for non-linear = 0.183). Similar results were found for cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms (Fig. 1b and 1c). Moreover, CT was correlated with more severe depressive (Table 2, model 3, β coefficient, 0.438 [95% CI, 0.222 and 0.654]), cognitive-affective (β coefficient, 0.311 [95% CI, 0.183 and 0.440]), somatic (β coefficient, 0.124 [95% CI, 0.012 and 0.235]) symptoms during follow-up. We did not observe a modifying role of age in the association between CT and depressive (Table S4 in the Supplementary, P-value for interaction term = 0.162), cognitive-affective (P-value for interaction term = 0.055), and somatic (P-value for interaction term = 0.451) symptoms.

Figure 1

Dose–response associations between combined lifestyle and depressive symptoms during follow-up.

The solid line and dashed line represent the estimated values and their 95% CI. The adjusted covariates included follow-up time (follow-up years from baseline) and baseline factors, including age, sex, educational level, employment status, marital status, household income, the number of chronic diseases, childhood trauma, depressive symptoms (for depressive symptoms), cognitive-affective symptoms (for cognitive-affective symptoms) and somatic symptoms (for somatic symptoms). The specific locations of the three knots were 2, 4 and 5 healthy lifestyles, respectively.Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

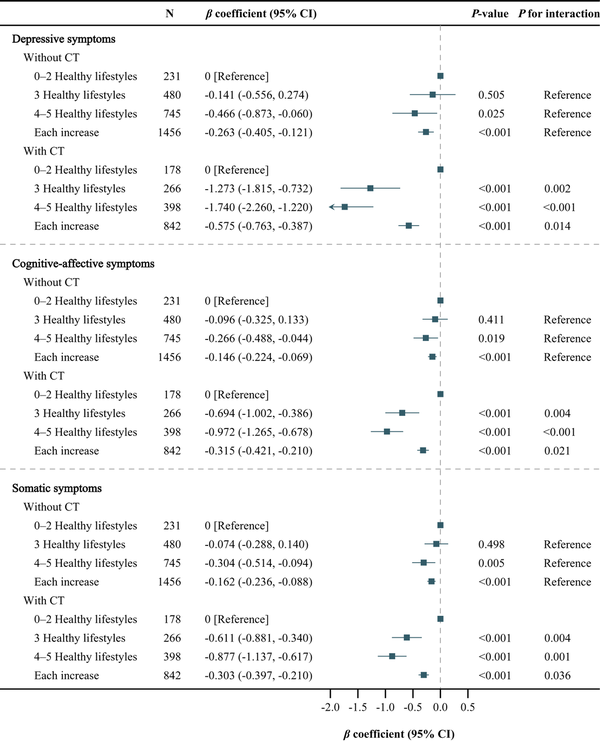

Interaction of combined lifestyle and CT on depressive symptoms

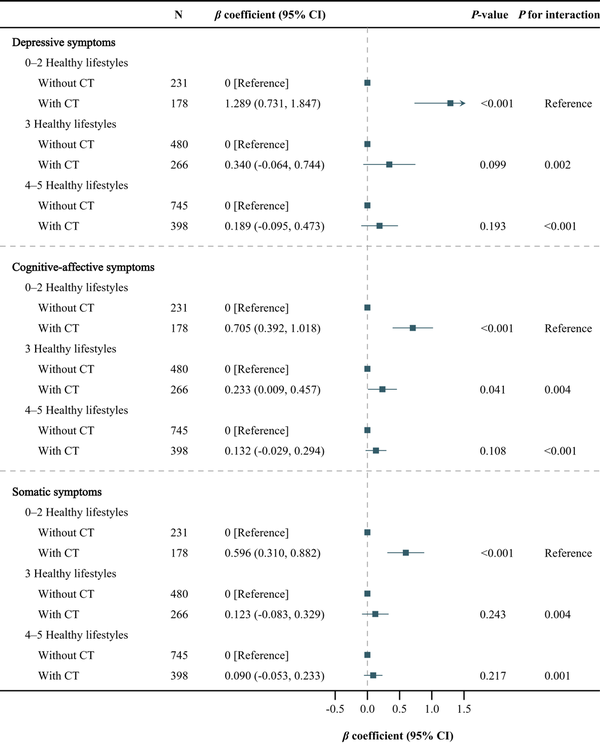

There existed a significant synergistic interaction between an overall healthy lifestyle and the absence of CT (Fig. 2, all P for interaction < 0.05). The CT-stratified analysis showed that compared with 0–2 healthy lifestyles, 3 healthy lifestyles were associated with milder depressive (β coefficient, −1.273 [95% CI, −1.815, −0.732]), cognitive-affective (β coefficient, −0.694 [95% CI, −1.002, −0.386]), and somatic (β coefficient, −0.611 [95% CI, −0.881, −0.340]) symptoms in participants with CT, but not in those without CT. Moreover, 4–5 healthy lifestyles were associated with milder depressive (β coefficient, −1.740 [95% CI, −2.260, −1.220]; −0.466 [95% CI, −0.873, −0.060]), cognitive-affective (β coefficient, −0.972 [95% CI, −1.265, −0.678]; −0.266 [95% CI, −0.488, −0.044]), and somatic (β coefficient, −0.877 [95% CI, −1.137, −0.617]; −0.304 [95% CI, −0.514, −0.094]) symptoms in both participants with and without CT, with a stronger association in those with CT. As shown in Fig. 3, the lifestyle-stratified analysis showed that CT was associated with more severe depressive (β coefficient, 1.289 [95% CI, 0.731, 1.847]) and somatic (β coefficient, 0.596 [95% CI, 0.310, 0.882]) symptoms among participants with 0–2 healthy lifestyles, but not among those with 3 or 4–5 healthy lifestyles. CT was associated with more severe cognitive-affective symptoms among participants with 0–2 (β coefficient, 0.705 [95% CI, 0.392, 1.018]) or 3 (β coefficient, 0.233 [95% CI, 0.009 and 0.457]) healthy lifestyles, but not among those with 4–5 healthy lifestyles.

Figure 2

Association of combined lifestyle with depressive symptoms during follow-up, stratified by childhood trauma.

The adjusted covariates included follow-up time (follow-up years from baseline) and baseline factors, including age, sex, educational level, employment status, marital status, household income, the number of chronic diseases, depressive symptoms (for depressive symptoms), cognitive-affective symptoms (for cognitive-affective symptoms) and somatic symptoms (for somatic symptoms).Abbreviations: CT, childhood trauma; CI, confidence interval.

Figure 3

Association of childhood trauma with depressive symptoms during follow-up, stratified by combined lifestyle.

The adjusted covariates included follow-up time (follow-up years from baseline) and baseline factors, including age, sex, educational level, employment status, marital status, household income, the number of chronic diseases, depressive symptoms (for depressive symptoms), cognitive-affective symptoms (for cognitive-affective symptoms), and somatic symptoms (for somatic symptoms).Abbreviations: CT, childhood trauma; CI, confidence interval.

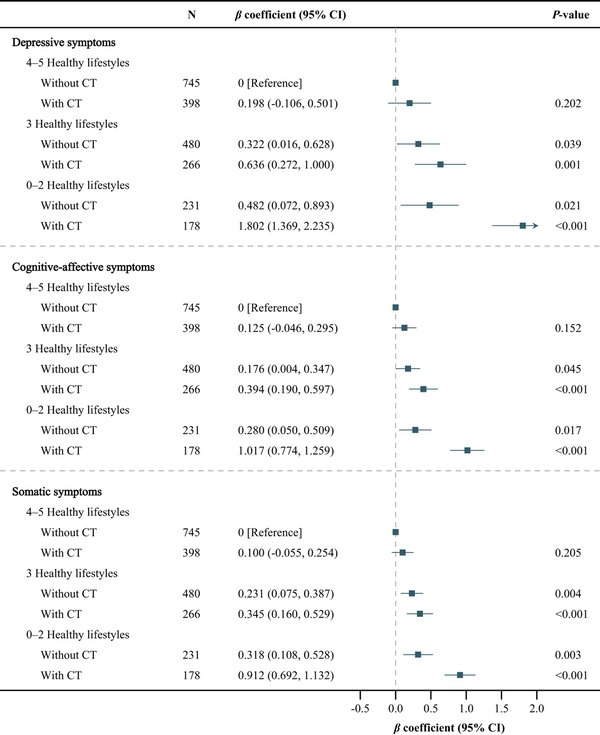

Joint associations of CT and combined lifestyle with depressive symptoms

Compared with participants with 4–5 healthy lifestyles and without CT (Fig. 4), except for those with 4–5 healthy lifestyles and with CT, others showed more severe depressive, cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms during follow-up. Depressive (β coefficient, 1.802 [95% CI, 1.369, 2.235]), cognitive-affective (β coefficient, 1.017 [95% CI, 0.774, 1.259]), somatic (β coefficient, 0.912 [95% CI, 0.692, 1.132]) symptoms were the most severe among those with 0–2 healthy lifestyles and with CT.

Figure 4

Joint associations of childhood trauma and combined lifestyle with depressive symptoms during follow-up.

The adjusted covariates included follow-up time (follow-up years from baseline) and baseline factors, including age, sex, educational level, employment status, marital status, household income, the number of chronic diseases, depressive symptoms (for depressive symptoms), cognitive-affective symptoms (for cognitive-affective symptoms), and somatic symptoms (for somatic symptoms).Abbreviations: CT, childhood trauma; CI, confidence interval.

Sensitivity analyses

The results of the three sensitivity analyses were almost consistent with those of the main analysis (Table S5–S10 and Figure S2 in the Supplementary). All statistically significant β coefficients still held statistical significance.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study of 2298 adults with subthreshold depression, better adherence to healthy lifestyles was associated with subsequent milder depressive symptoms and their subtypes, and there existed a significant synergistic interaction between an overall healthy lifestyle and the absence of CT. The CT-stratified analysis showed that healthy lifestyle was associated with subsequent milder depressive symptoms and their subtypes in both adults with and without CT, with a stronger association in those with CT. More importantly, the lifestyle-stratified analysis showed that CT was associated with subsequent more severe depressive symptoms and their subtypes in adults with 0–2 healthy lifestyles, but not in those with 4–5 healthy lifestyles, suggesting that an overall healthy lifestyle might mitigate or even offset the associations of CT with depressive symptoms and their subtypes in adults with subthreshold depression.

Comparison with other studies

A meta-analysis of five cohort studies has reported that adherence to an overall healthy lifestyle is essential for the primary prevention of depressive symptoms in the general population (Wang et al., ). Subsequent cohort studies from multiple countries have also shown similar results in the general population (Cao et al., ; Collins et al., ; Dabravolskaj et al., ; Werneck et al., ). Similarly, we found that regardless of the presence of CT, adopting an overall healthy lifestyle was associated with milder depressive symptoms among individuals with subthreshold depression, suggesting that the benefits of an overall healthy lifestyle for depressive symptoms might be generalized to the population with subthreshold depression, a high-risk group for depressive disorders (Zhang et al., ). Lifestyle is a modifiable factor and changing it is low cost. Our findings provide effective, feasible and low-cost strategies for alleviating depressive symptoms in individuals with subthreshold depression, which is of great significance for preventing depressive disorders. Randomized controlled trials are needed to validate our findings in the population with subthreshold depression.

Furthermore, despite the high heterogeneity of depressive symptoms, we found that an overall healthy lifestyle was associated with subsequent milder somatic and cognitive-affective symptoms, reflecting the comprehensive benefits of an overall healthy lifestyle for depressive symptoms. At present, there is a lack of research exploring the associations between combined lifestyle and subtypes of depressive symptoms, with only a few studies evaluating the associations between a single lifestyle (i.e. physical activity and BMI) and subtypes of depressive symptoms in the general population (Chu et al., ; Wu et al., ). Therefore, further studies are needed to validate our findings across different countries and populations.

CT is widely recognized as a risk factor for depressive symptoms and their subtypes (Humphreys et al., ; Iob et al., , ). Our longitudinal study also showed similar findings. Importantly, CT cannot be changed once it occurs and its adverse effects may persist over a lifetime. We found that an overall healthy lifestyle mitigated the associations of CT with subsequent depressive symptoms and their subtypes. Interestingly, stratified analyses of combined lifestyle showed that CT was associated with more severe depressive symptoms and their subtypes among participants with 0–2 healthy lifestyles, but not among those with 4–5 healthy lifestyles, indicating that adherence to an adequate healthy lifestyle might offset the adverse effects of CT on depressive symptoms in adults with subthreshold depression. A relevant biological mechanism might be that CT leads to depressive symptoms primarily by causing the dysregulation of the HPA axis and immune inflammation (Humphreys et al., ), whereas adherence to an overall healthy lifestyle is beneficial in maintaining the homeostasis of the HPA axis and immune inflammation, thus an overall healthy lifestyle might mitigate the adverse effects of CT on depressive symptoms (Lopresti et al., ). Our findings provide preliminary clues as to how individuals with CT can escape or alleviate the adverse effects of CT on depressive symptoms. To date, few studies have been conducted to target the modifying role of combined lifestyle in the association between CT and depressive symptoms. Several cross-sectional studies of the general population have found that a single lifestyle might modify the association between CT and depressive symptoms, such as physical activity (Boisgontier et al., ; Royer and Wharton, ), drinking status (Rice et al., ), sleep (Masuya et al., ) and BMI (Ramirez and Milan, ; Zhang et al., ), which to some extent supports our findings. Future studies are needed to verify that an overall healthy lifestyle can alleviate the association between CT and depressive symptoms, and to elucidate the biological mechanisms involved.

Strengths and limitations

The advantage of this study is that the 3.5-year prospective cohort study design allowed for the identification of temporality between lifestyles and depressive symptoms. In addition, we constructed an overall healthy lifestyle score to comprehensively evaluate the complex associations of lifestyle with depressive symptoms and their subtypes. Nevertheless, several potential limitations should also be noted. First, all variables were collected through the self-reported questionnaire, so reporting bias was inevitable. Second, the retrospective assessment of CT might lead to recall bias. Third, we did not collect information on the specific age at which CT occurred, so we cannot further explore the association between CT at different ages and depressive symptoms. Fourth, since the information on diet was not collected in the SDC study, we did not include diet in healthy lifestyle scores. Thus, our findings cannot suggest whether a healthy lifestyle, including diet, is associated with milder depressive symptoms. Fifth, since this study only involved community residents in Shenzhen, China, the findings need to be carefully extrapolated to other regions in China or other countries. Finally, due to the nature of observational studies, the impact of unmeasured confounding factors (e.g. genotype) on the results cannot be eliminated, hindering the determination of the causal association.

Conclusions

In this 3.5-year longitudinal study of adults with subthreshold depression, better adherence to healthy lifestyles, including no current drinking, no current smoking, regular physical exercise, optimal sleep duration and no obesity, was associated with subsequent milder depressive symptoms and their subtypes, with a stronger association in adults with CT than those without CT. Furthermore, better adherence to healthy lifestyles significantly mitigated the CT-induced exacerbation of depressive symptoms and their subtypes. Our findings emphasize the benefits of adherence to an overall healthy lifestyle for adults with subthreshold depression, especially those with CT.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all participants and field investigators of the Depression Cohort in China (DCC) study.

References

- Bernstein DP, Stein JA, Newcomb MD, Walker E, Pogge D, Ahluvalia T, Stokes J, Handelsman L, Medrano M, Desmond D and Zule W (2003) Development and validation of a brief screening version of the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect 27, 169–190.10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00541-0

- Boisgontier MP, Orsholits D, von Arx M, Sieber S, Miller MW, Courvoisier D, Iversen MD, Cullati S and Cheval B (2020) Adverse childhood experiences, depressive symptoms, functional dependence, and physical activity: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Physical Activity and Health 17, 790–799.10.1123/jpah.2019-0133

- Cao Z, Yang H, Ye Y, Zhang Y, Li S, Zhao H and Wang Y (2021) Polygenic risk score, healthy lifestyles, and risk of incident depression. Translational Psychiatry 11, 189.10.1038/s41398-021-01306-w

- Chu K, Cadar D, Iob E and Frank P (2023) Excess body weight and specific types of depressive symptoms: Is there a mediating role of systemic low-grade inflammation? Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 108, 233–244.10.1016/j.bbi.2022.11.016

- Collins S, Hoare E, Allender S, Olive L, Leech RM, Winpenny EM, Jacka F and Lotfalian M (2023) A longitudinal study of lifestyle behaviours in emerging adulthood and risk for symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Journal of Affective Disorders 327, 244–253.10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.010

- Dabravolskaj J, Veugelers PJ, Amores A, Leatherdale ST, Patte KA and Maximova K (2023) The impact of 12 modifiable lifestyle behaviours on depressive and anxiety symptoms in middle adolescence: Prospective analyses of the Canadian longitudinal COMPASS study. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 20, 45.10.1186/s12966-023-01436-y

- GBD 2021 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators (2024) Global incidence, prevalence, years lived with disability (YLDs), disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs), and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 371 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories and 811 subnational locations, 1990-2021: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet 403, 2133–2161.10.1016/S0140-6736(24)00757-8

- Huang MC, Schwandt ML, Ramchandani VA, George DT and Heilig M (2012) Impact of multiple types of childhood trauma exposure on risk of psychiatric comorbidity among alcoholic inpatients. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 36, 1099–1107.10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01695.x

- Humphreys KL, LeMoult J, Wear JG, Piersiak HA, Lee A and Gotlib IH (2020) Child maltreatment and depression: A meta-analysis of studies using the Childhood Trauma Questionnaire. Child Abuse and Neglect 102, 104361.10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104361

- Iob E, Baldwin JR, Plomin R and Steptoe A (2021) Adverse childhood experiences, daytime salivary cortisol, and depressive symptoms in early adulthood: A longitudinal genetically informed twin study. Translational Psychiatry 11, 420.10.1038/s41398-021-01538-w

- Iob E, Kirschbaum C and Steptoe A (2020a) Persistent depressive symptoms, HPA-axis hyperactivity, and inflammation: The role of cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms. Molecular Psychiatry 25, 1130–1140.10.1038/s41380-019-0501-6

- Iob E, Lacey R and Steptoe A (2020b) Adverse childhood experiences and depressive symptoms in later life: Longitudinal mediation effects of inflammation. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 90, 97–107.10.1016/j.bbi.2020.07.045

- Jia J, Zhao T, Liu Z, Liang Y, Li F, Li Y, Liu W, Li F, Shi S, Zhou C, Yang H, Liao Z, Li Y, Zhao H, Zhang J, Zhang K, Kan M, Yang S, Li H, Liu Z, Ma R, Lv J, Wang Y, Yan X, Liang F, Yuan X, Zhang J, Gauthier S and Cummings J (2023) Association between healthy lifestyle and memory decline in older adults: 10 year, population based, prospective cohort study. BMJ-British Medical Journal 380, e072691.

- Jiang Z, Xu H, Li S, Liu Y, Jin Z, Li R, Tao X and Wan Y (2022) Childhood maltreatment and depressive symptoms among Chinese college students: A moderated mediation model of adult attachment styles and physical activity. Journal of Affective Disorders 309, 63–70.10.1016/j.jad.2022.04.100

- Jin G, Lv J, Yang M, Wang M and Li L (2020) Genetic risk, incident gastric cancer, and healthy lifestyle: A meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies and prospective cohort study. The Lancet Oncology 21, 1378–1386.10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30460-5

- Liao DD, Dong M, Ding KR, Hou CL, Tan WY, Ke YF, Jia FJ and Wang SB (2023) Prevalence and patterns of major depressive disorder and subthreshold depressive symptoms in south China. Journal of Affective Disorders 329, 131–140.10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.069

- Liao YH, Fan BF, Zhang HM, Guo L, Lee Y, Wang WX, Li WY, Gong MQ, Lui LMW, Li LJ, Lu CY and McIntyre RS (2021) The impact of COVID-19 on subthreshold depressive symptoms: A longitudinal study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences 30, e20.10.1017/S2045796021000044

- Liao Y, Zhang H, Guo L, Fan B, Wang W, Teopiz KM, Lui LMW, Lee Y, Li L, Han X, Lu C and McIntyre RS (2022) Impact of cognitive-affective and somatic symptoms in subthreshold depression transition in adults: Evidence from Depression Cohort in China (DCC). Journal of Affective Disorders 315, 274–281.10.1016/j.jad.2022.08.009

- Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, Black T, Brewer LC, Foraker RE, Grandner MA, Lavretsky H, Perak AM, Sharma G and Rosamond W (2022) Life’s Essential 8: Updating and Enhancing the American Heart Association’s Construct of Cardiovascular Health: A Presidential Advisory From the American Heart Association. Circulation 146, e18–e43.10.1161/CIR.0000000000001078

- Lopresti AL, Hood SD and Drummond PD (2013) A review of lifestyle factors that contribute to important pathways associated with major depression: Diet, sleep and exercise. Journal of Affective Disorders 148, 12–27.10.1016/j.jad.2013.01.014

- Masuya J, Morishita C, Ono M, Honyashiki M, Tamada Y, Seki T, Shimura A, Tanabe H and Inoue T (2024) Moderation by better sleep of the association among childhood maltreatment, neuroticism, and depressive symptoms in the adult volunteers: A moderated mediation model. PloS One 19, e0305033.10.1371/journal.pone.0305033

- Qie R, Huang H, Sun P, Bi X, Chen Y, Liu Z, Chen Q, Zhang S, Liu Y, Wei J, Chen M, Zhong J, Qi Z, Yao F, Gao L, Yu H, Liu F, Zhao Y, Chen B, Wei X, Qin S, Du Y, Zhou G, Yu F, Ba Y, Shang T, Zhang Y, Zheng S, Xie D, Chen X, Liu X, Zhu C, Wu W, Feng Y, Wang Y, Xie Y, Hu Z, Wu M, Yan Q, Zou K and Zhang Y (2024) Combined healthy lifestyles and risk of depressive symptoms: A baseline survey in China. Journal of Affective Disorders 363, 152–160.10.1016/j.jad.2024.07.134

- Ramirez JC and Milan S (2016) Childhood sexual abuse moderates the relationship between obesity and mental health in low-income women. Child Maltreatment 21, 85–89.10.1177/1077559515611246

- Rice SM, Kealy D, Seidler ZE, Walton CC, Oliffe JL and Ogrodniczuk JS (2021) Male-type depression symptoms in young men with a history of childhood sexual abuse and current hazardous alcohol use. Psychiatry Research 304, 114110.10.1016/j.psychres.2021.114110

- Rodríguez MR, Nuevo R, Chatterji S and Ayuso-Mateos JL (2012) Definitions and factors associated with subthreshold depressive conditions: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry 12, 181.10.1186/1471-244X-12-181

- Rowland G, Hindman E, Hassmén P, Radford K, Draper B, Cumming R, Daylight G, Garvey G, Delbaere K and Broe T (2023) Depression, childhood trauma, and physical activity in older Indigenous Australians. International Psychogeriatrics 35, 259–269.10.1017/S1041610221000132

- Royer MF and Wharton C (2022) Physical activity mitigates the link between adverse childhood experiences and depression among U.S. adults. PloS One 17, e0275185.10.1371/journal.pone.0275185

- Shi J, Han X, Liao Y, Zhao H, Fan B, Zhang H, Teopiz KM, Song W, Li L, Guo L, Lu C and McIntyre RS (2023) Associations of stressful life events with subthreshold depressive symptoms and major depressive disorder: The moderating role of gender. Journal of Affective Disorders 325, 588–595.10.1016/j.jad.2023.01.050

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K and Williams JB (1999) Validation and utility of a self-report version of PRIME-MD: The PHQ primary care study. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders. Patient Health Questionnaire. JAMA 282, 1737–1744.10.1001/jama.282.18.1737

- Sun X, Li Y, Yu C and Li L (2017) Reliability and validity of depression scales of Chinese version: A systematic review. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi= Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi 38, 7.

- Tang Z, Yang X, Tan W, Ke Y, Kou C, Zhang M, Liu L, Zhang Y, Li X, Li W and Wang SB (2024) Patterns of unhealthy lifestyle and their associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms among Chinese young adults: A latent class analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 352, 267–277.10.1016/j.jad.2024.02.055

- Vrany EA, Berntson JM, Khambaty T and Stewart JC (2016) Depressive symptoms clusters and insulin resistance: race/ethnicity as a moderator in 2005-2010 NHANES Data. Annals of Behavioral Medicine: A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine 50, 1–11.10.1007/s12160-015-9725-0

- Wang H, Liao Y, Guo L, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Lai W, Teopiz KM, Song W, Zhu D, Li L, Lu C, Fan B and McIntyre RS (2022) Association between childhood trauma and medication adherence among patients with major depressive disorder: The moderating role of resilience. BMC Psychiatry 22, 644.10.1186/s12888-022-04297-0

- Wang X, Arafa A, Liu K, Eshak ES, Hu Y and Dong JY (2021) Combined healthy lifestyle and depressive symptoms: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Journal of Affective Disorders 289, 144–150.10.1016/j.jad.2021.04.030

- Werneck AO, Peralta M, Tesler R and Marques A (2022) Cross-sectional and prospective associations of lifestyle risk behaviors clustering with elevated depressive symptoms among middle-aged and older adults. Maturitas 155, 8–13.10.1016/j.maturitas.2021.09.010

- Wu Y, Kong X, Feng W, Xing F, Zhu S, Lv B, Liu B, Li S, Sun Y and Wu Y (2024) A longitudinal study of the mediator role of physical activity in the bidirectional relationships of cognitive function and specific dimensions of depressive symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders 366, 146–152.10.1016/j.jad.2024.08.175

- Xie X, Li Y, Liu J, Zhang L, Sun T, Zhang C, Liu Z, Liu J, Wen L, Gong X and Cai Z (2023) The relationship between childhood maltreatment and non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents with depressive disorders. Psychiatry Research 331, 115638.

- Zhang H, Liao Y, Han X, Fan B, Liu Y, Lui LMW, Lee Y, Subramaniapillai M, Li L, Guo L, Lu C and McIntyre RS (2022) Screening depressive symptoms and incident major depressive disorder among chinese community residents using a mobile app-based integrated mental health care model: Cohort study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 24, e30907.10.2196/30907

- Zhang R, Peng X, Song X, Long J, Wang C, Zhang C, Huang R and Lee TMC (2023a) The prevalence and risk of developing major depression among individuals with subthreshold depression in the general population. Psychological Medicine 53, 3611–3620.10.1017/S0033291722000241

- Zhang YB, Chen C, Pan XF, Guo J, Li Y, Franco OH, Liu G and Pan A (2021) Associations of healthy lifestyle and socioeconomic status with mortality and incident cardiovascular disease: Two prospective cohort studies. BMJ-British Medical Journal 373, n604.

- Zhang Y, Li Y, Jiang T and Zhang Q (2023b) Role of body mass index in the relationship between adverse childhood experiences, resilience, and mental health: A multivariate analysis. BMC Psychiatry 23, 460.

- Zhao XF, Zhang YL, Li LF, Zhou YF and Yang SC (2005) Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of childhood trauma questionnaire. Chinese Journal of Clinical Rehabilitation 9, 105–107.