Introduction

Myringoplasty using the underlay or overlay technique is the most common procedure for repairing tympanic membrane perforations (TMPs). Underlay tympanoplasty, in which the graft is placed medial to the annulus and the malleus, is the most commonly used technique. In the overlay technique, first described by Shea in 1960 and modified by Sheehy and Glasscock in 1967, the graft is placed lateral to the annulus and over the fibrous layer of the tympanic membrane remnant. Subsequent modified techniques include the 3-point fix technique, loop overlay tympanoplasty with a superiorly based tympanomeatal flap and overlay placement of the graft, sandwich graft tympanoplasty, over-under tympanoplasty in which the graft is placed over the malleus and under the annulus, and mediolateral graft tympanoplasty. Furthermore, with the development of endoscopic ear surgery, the graft material changed gradually from skin to fascia, perichondrium, and cartilage. However, packing the external auditory canal (EAC) and tympanic cavity with biological material after surgery is essential regardless of the technique used to support the graft. Although EAC packing is a common procedure, few studies have investigated the effects of packing removal time on healing; therefore, we assessed the effects of packing duration in patients with chronic TMPs who underwent endoscopic myringoplasty.

Materials and Methods

Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethical Review Board of Yiwu Central Hospital (Yiwu, Zhejiang, China). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Methods

Our study was a retrospective review of 137 patients with unilateral TMPs who underwent endoscopic “push-through” cartilage myringoplasty between January 2013 and March 2016. The inclusion criteria were unilateral TMPs, no active otorrhea for at least 3 months prior to surgery, and conductive hearing loss no greater than 40 dB in any frequency for any ears at the time of surgery. All patients underwent endoscopic cartilage myringoplasty and were followed up for at least 3 months. Patients with ossicular chain disease and cholesteatoma were excluded from the study.

Perforation size, defined as the proportion of the entire tympanic membrane, was classified as small (up to one-third of the tympanic membrane), medium (one-third to two-thirds of the tympanic membrane), and large (more than two-thirds of the tympanic membrane). The pure-tone average was calculated as the mean of the pure-tone hearing thresholds at 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 kHz. The air-bone gap (ABG) was defined as the mean of the differences between the air conduction thresholds and the bone conduction thresholds at 0.5, 1.0, 2.0, and 3.0 kHz. All surgeries were performed under general anesthesia by the same surgeon. The EAC packing was removed 2 weeks after surgery (early group) or 4 weeks after surgery (late group).

Surgical Technique

Patients were placed in the supine position with the head elevated 30° and rotated away from the surgeon, and the video equipment was placed opposite the surgeon. Surgery was performed under general anesthesia. Cartilage from a single-sided perichondrium graft was harvested through a 1-cm incision medial to the free border of the tragus. The diameter of the perforation was measured using a sterile piece of aluminum foil. The cartilage–perichondrium graft was trimmed based on the size of the perforation and involvement of the malleus. The tragal cartilage was not thinned out.

The perforation edges were visualized under a 0° rigid endoscope and de-epithelialized using an angled pick. The middle ear was tightly packed with biodegradable NasoPore (Stryker, Kalamazoo, Michigan) soaked in antibiotic ointment to the level of the perforation. It was not necessary to elevate the tympanomeatal flap using this technique. The cartilage–perichondrium graft, which was slightly larger than the perforation, was pushed through the perforation and placed in an underlay fashion to occlude the perforation with the perichondrium layer facing laterally.

For perforations involving the malleus, the handle of the malleus was denuded of epithelium, the cartilage on one side was freed from the perichondrium, and a notch was made in the cartilage, but not the perichondrium, to accommodate the exposed malleus handle. This allowed the cuff of the graft to fit snugly against the malleus handle. Then, the free perichondrium was elevated and placed lateral to the malleus handle.

The EAC was packed with biodegradable NasoPore soaked in antibiotic ointment and then packed with gauze soaked in antibiotic ointment up to the tragal incision. The tragal incision was not sutured, and a small dressing was used to cover the auricle.

Postoperative Follow-Up

All patients received a course of oral antibiotics for 1 week after surgery. The packing gauze soaked in antibiotic ointment was removed from the EAC 2 weeks after surgery in all patients. The biodegradable NasoPore fragments were removed from the EAC 2 weeks after surgery in the early group and 4 weeks after surgery in the late group, which allowed the graft to be visualized. All patients were scheduled for regular follow-up visits 2 and 4 weeks, 2 and 3 months after surgery, and endoscopic examinations were performed. Pure-tone audiograms were recorded 3 months after surgery. Graft success was defined as the presence of an intact graft assessed using a 0° endoscope, and graft failure was defined as the presence of residual perforation 3 months after surgery.

Statistical Analysis

Data are expressed as means (standard deviation) for quantitative variables and as frequencies and percentages for qualitative variables. Comparisons between groups were made using independent sample t tests for quantitative variables and chi-square tests for qualitative variables. Paired t tests were performed to detect differences in the related quantitative measurements (ABG). Statistical analyses were performed using IBM-SPSS software version 20 (IBM Corp, Armonk, New York); P values <.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Demographic Data

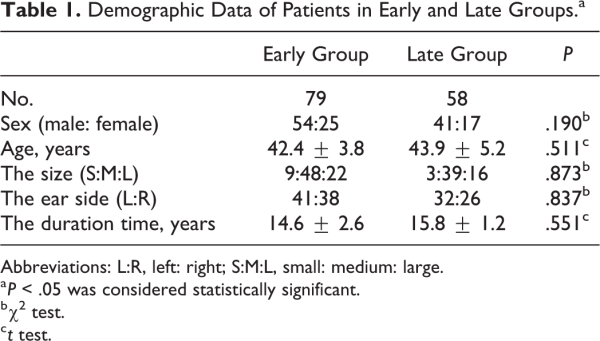

The study included 137 patients (79 in the early group and 58 in the late group). The tragal incision had healed by postoperative week 2 in all of the patients. The average age, sex, perforation duration and size, and the side of ear were matched (P > .005) between groups (Table 1).

Endoscopic Observations

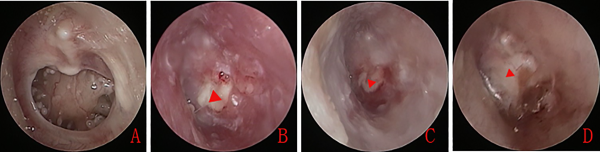

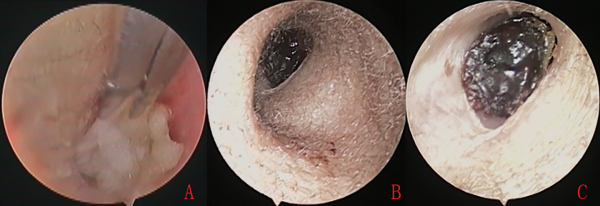

In the early group, a large amount of exudate was present in the EAC and on the surface of the graft. The cartilage grafts and tympanic membrane remnants were irregular 2 weeks after surgery, and no epithelialization was observed on the surface of the cartilage grafts. At 2 months after surgery, the cartilage grafts and tympanic membrane remnants remained irregular, the eardrum did not regain a normal appearance, and only partial epithelialization was visible on the surface of the cartilage grafts. Moreover, a cartilage bulge was visible in most of the eardrums. Although the eardrums gradually thinned over time, a slight bulge remained 3 months after surgery (Figure 1).

Figure 1

Preoperative large tympanic membrane perforation (A). The nasopore packing was removed 2 weeks after surgery. Endoscopic examination revealed no epithelialization of the cartilage graft (B). Cartilage graft showing partial epithelialization 2 weeks after surgery (C). The cartilage graft remained irregular 1 month after surgery (D). The red triangle indicates the cartilage graft.

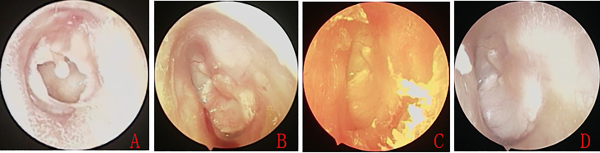

In the late group, the Nasopore facilitated blood uptake and fragmentation, however, it was not liquefied and absorbed but formed composite blood clot (Figure 2). Little or no exudate was present in the EAC or on the surface of the grafts after the removal of Nasopore composite blood clot, the grafts and tympanic membrane remnants were smooth, and epithelialization was nearly complete 4 weeks after surgery. The eardrum was thicker, but otherwise appeared completely normal 2 to 3 months after surgery (Figure 3).

Figure 2

The external auditory canal (EAC) was packed with biodegradable nasopore (A), the nasopore facilitated blood uptake and fragmentation, and formed nasopore composite blood clot at postoperative 2 weeks (B), and nasopore composite blood clot still remained at postoperative 4 weeks (C).

Figure 3

Preoperative large tympanic membrane perforation (A). The nasopore packing was removed 4 weeks after surgery. Endoscopic examination revealed nearly complete epithelialization of the cartilage graft (B). Epithelialization was complete (C), and the eardrum was smooth (D) 2 to 3 months after surgery.

Graft Take Rate and Complications

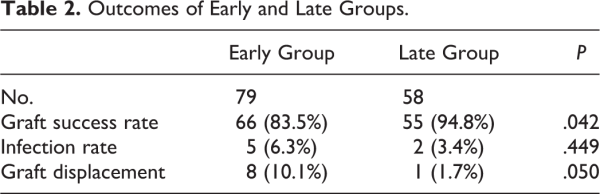

All of the patients were followed up for at least 3 months. The graft success rates and complications are shown in Table 2. The graft success rate was significantly lower in the early group (83.5% [66/79]) than in the late group (94.8% [55/58]; P = .042) 3 months after surgery. Postoperative purulent otorrhea was observed in 5 (6.3%) patients in the early group and in 2 (3.4%) patients in the late group. The middle ear infection rate was not significantly different between groups (P = .449). Grafts were displaced in 8 (10.1%) patients in the early group and in 1 (1.7%) patient in the late group (P = .050).

Hearing Gains

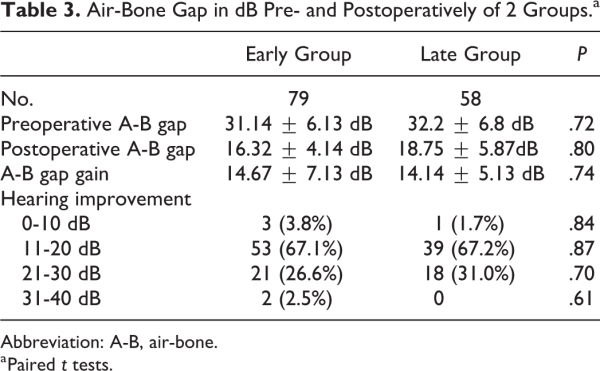

Table 3 shows the preoperative and 3-month postoperative ABG values. In the early group, the mean preoperative ABG was 31.14 ± 6.13 dB and the mean postoperative value was 16.32 ± 4.14 dB resulting in a mean gain of 14.67 ± 7.13 dB (P < .001). In late group, the mean preoperative ABG was 32.2 ± 6.8 dB, and the mean postoperative value was 18.75 ± 5.87 dB resulting in a mean gain of 14.14 ± 5.13 dB (P < .001). However, the mean gain in hearing threshold was not significantly different between groups (P = .74).

Discussion

External auditory canal and middle ear packing promotes hemostasis in both the underlay or overlay myringoplasty techniques and is widely used in otologic surgery. Moreover, packing provides a scaffold to support tympanic membrane grafts and the ossicular chain. Several packing materials have been studied, including gelfoam, merocel, silastic, antibiotic ointment, and NasoPore., Gelfoam is the most commonly used packing material in otologic surgery. The optimal packing duration has not been established. While most clinicians remove EAC packing 1 to 2 weeks after surgery,-, a few have reported removing the packing 3 to 4 weeks after surgery., However, the effect of packing duration on the graft success rate and tympanic membrane appearance has not been investigated.

We found that 3 months after surgery, the graft success rate was significantly lower in the early group (83.5% [66/79]) than in the late group (94.8% [55/58]; P = .042). It may be that packing fixes the graft in place ensuring close contact between the graft and the tympanic membrane remnant, thus preventing graft displacement and reperforation. A previous study concluded that an adequate area of contact between the graft and tympanic membrane remnant was fundamental to the successful closure of a perforation. Histological studies have shown that NasoPore does not expand when moist, and thus cannot displace the graft. However, excessive pressure in the middle ear may cause the graft to partially fall into the EAC or displace the graft when the EAC packing material is removed too soon.

The Nasopore facilitated blood uptake and fragmentation, however, it was not liquefied and absorbed but formed Nasopore composite blood clot in the late group in this study. It did not also lead to the infection of the EAC. The infection rate was not significantly different between groups. Usually, persistence of mass of Nasopore is at least 3 weeks in the middle ear cavity and nasal cavity., However, the Nasopore is fragmented by repeatedly spraying with saline solution and is thus gradually flushed out following nasal surgery. Nasopore is believed to provide gentle compression and offer sufficient wound support during the critical healing period through the absorption of effusion and blood. The more effusion was present in the EAC of the early group than that of the late group when the packing was removed. Only a small amount of exudate was present 4 weeks after surgery in most cases in present study. Also, Nasopore can accelerate wound healing by providing a moist dressing environment. The Nasopore composite blood clot not only well maintain the durability for supporting cartilage graft but also acts as a scaffold for epithelial cell migration and slowly releases growth factors to promote eardrum healing. Song et al used gelfoam with blood clot from the refreshed edges to repair chronic TMPs following ventilation tube insertion and achieved successful tympanic membrane closure in 90.6% of the patients.

We found that NasoPore facilitated re-epithelialization. Epithelialization was nearly complete or proliferative epithelium covered a large proportion of the cartilage surface in the late group, whereas little proliferative epithelium was found in the early group. A prospective, randomized double-blind study comparing biodegradable (NasoPore) and nonbiodegradable packing found significantly better re-epithelialization in the NasoPore group on day 10 after surgery and nearly complete epithelialization 30 days after surgery. A histological study found no erosion or degeneration of the epithelia at NasoPore packing sites in the middle ear cavity 20 days after surgery. In our early group, the cartilage graft and remnant tympanic membrane were irregular at the 2-week and 2-month postoperative follow-up, and the eardrum appearance was not normal with a bulge in most cases. Although the eardrums gradually thinned over time, a slight bulge remained 3 months after surgery, while in the late group the cartilage grafts and tympanic membrane remnants were smooth, and epithelialization was nearly complete 4 weeks after surgery. The eardrums appeared normal except that they remained thicker 2 to 3 months after surgery. The limitations of our study include the absence of histological data, the short follow-up period, and the fact that it was a retrospective rather than a prospective study and not a randomized controlled trial.

Conclusion

Delaying the removal of the EAC packing after endoscopic cartilage myringoplasty may promote tympanic membrane better healing and cartilage graft epithelialization and improve the appearance of the eardrum.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Science and Technology Agency of Yiwu city, China (Grants#2018-3-76).

Zhengcai Lou

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1085-9033

References

- 1. Sergi B, Galli J, De Corso E, Parrilla C, Paludetti G. Overlay versus underlay myringoplasty: report of outcomes considering closure of perforation and hearing function. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31(6):366–371.

- 2. Shea JJ Jr. Vein graft closure of eardrum perforations. J Laryngol Otol. 1960;74:358–362.

- 3. Sheehy JL, Glasscock ME. Tympanic membrane grafting with temporalis fascia. Arch Otolaryngol. 1967;86(4):391–402.

- 4. Shim DB, Kim HJ, Kim MJ, Seok MI. Three-point fix tympanoplasty. Acta Otolaryngol. 2015;135(5):429–434.

- 5. Lee HY, Auo HJ, Kang JM. Loop overlay tympanoplasty for anterior or subtotal perforations. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2010;37(2):162–166.

- 6. Farrior JB. Sandwich graft tympanoplasty: a technique for managing difficult tympanic membrane perforation. Oper Tech Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;6(1):27–32.

- 7. Kartush JM, Michaelides EM, Becvarovski Z, LaRouere ML. Over-under tympanoplasty. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(5):802–807.

- 8. Jung TT, Park SK. Mediolateral graft tympanoplasty for anterior or subtotal tympanic membrane perforation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2005;132(4):532–536.

- 9. Singh M, Rai A, Bandyopadhyay S, Gupta SC. Comparative study of the underlay and overlay techniques of myringoplasty in large and subtotal perforations of the tympanic membrane. J Laryngol Otol. 2003;117(6):444–448.

- 10. Parelkar K, Thorawade V, Marfatia H, Shere D. Endoscopic cartilage tympanoplasty: full thickness and partial thickness tragal graft. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;(18):30343–30344.

- 11. Ayache S. Cartilaginous myringoplasty: the endoscopic transcanal procedure. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270(3):853–860.

- 12. Kaya I, Turhal G, Ozturk A, Gode S, Bilgen C, Kirazli T. Results of endoscopic cartilage tympanoplasty procedure with limited tympanomeatal flap incision. Acta Otolaryngol. 2017;137(11):1174–1177.

- 13. Huang G, Chen X, Jiang H. Effects of nasopore packing in the middle ear cavity of the guinea pig. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145(1):131–136.

- 14. Dogru S, Haholu A, Gungor A, et al. Histologic analysis of the effects of three different support materials within rat middle ear. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(2):177–182.

- 15. Wick CC, Arnaoutakis D, Kaul VF, Isaacson B. Endoscopic lateral cartilage graft tympanoplasty. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;157(4):683–689.

- 16. Nemade SV, Shinde KJ, Sampate PB. Comparison between clinical and audiological results of tympanoplasty with double layer graft (modified sandwich fascia) technique and single layer graft (underlay fascia and underlay cartilage) technique. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45(3):440–446.

- 17. Bluher AE, Mannino EA, Strasnick B. Longitudinal analysis of ‘‘window shade’’ tympanoplasty outcomes for anterior marginal tympanic membrane perforations. Otol Neurotol. 2019;40(3):e173–e177.

- 18. Jang SY, Lee KH, Lee SY, Yoon JS. Effects of nasopore packing on dacryocystorhinostomy. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2013;27(2):73–80.

- 19. Kastl KG, Reichert M, Scheithauer MO, et al. Patient comfort following FESS and nasopore® packing, a double blind, prospective, randomized trial. Rhinology. 2014;52(1):60–65.

- 20. Shoman N, Gheriani H, Flamer D, Javer A. Prospective, double-blind, randomized trial evaluating patient satisfaction, bleeding, and wound healing using biodegradable synthetic polyurethane foam (nasopore) as a middle meatal spacer in functional endoscopic sinus surgery. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;38(1):112–118.

- 21. Lou Z. Late crust formation as a predictor of healing of traumatic, dry, and minor-sized tympanic membrane perforations. Am J Otolaryngol. 2013;34(4):282–286.

- 22. Song JS, Corsten G, Johnson LB. Evaluating short and long term outcomes following pediatric myringoplasty with gelfoam graft for tympanic membrane perforation following ventilation tube insertion. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;48(1):39.

- 23. Burduk PK, Wierzchowska M, Grześkowiak B, Kaźmierczak W, Wawrzyniak K. Clinical outcome and patient satisfaction using biodegradable (nasopore) and non-biodegradable packing, a double-blind, prospective, randomized study. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2017;83(1):23–28.