Introduction

Type 3 laryngomalacia (LM) is the least common and the severest form of LM characterized by a posteriorly displaced and retroflexed epiglottis with prolapse of the epiglottis into the airway. Epiglottic prolapse (EP) can also present as obstructive sleep apnea in children with or without lingual tonsillar hypertrophy and can also be associated with lymphangiomas or other lesions involving the base of the tongue. In all these cases, even though the underlying cause is different, EP presents a unique management challenge.

Various techniques have been described for epiglottopexy which include the use of coblation or carbon dioxide laser to de-mucosalize the lingual surface of the epiglottis, vallecula, and adjacent base of tongue followed by placement of an endolaryngeal anchoring stitch between the epiglottis and the tongue base., Even though endolaryngeal suturing is a viable option in older children, in infants, endolaryngeal suturing is not only technically challenging considering the limited exposure which severely constraints instrument manipulation but can also be associated with stitch breakdown due to the inability of the stitch to achieve enough depth through the base of the tongue. To obviate the need for endolaryngeal suturing, the use of a Lichtenberger’s needle carrier for passing transfixation sutures from the epiglottis through the tongue base and tied transcervically has been proposed. Even though the technique achieves epiglottic suspension, its widespread usage is limited due to the unavailability of a specialized non-FDA-approved instrument. In the present article, we describe a simple technique of transcervical epiglottopexy (TE) using an exo-endolaryngeal technique, with easily available instruments.

Materials and Methods

The surgical procedure is described in a 2-month-old child with a history of stridor and respiratory obstruction, who on flexible laryngoscopy revealed a lingual thyroglossal duct cyst (TGC) with type 3 LM associated with complete EP. A computed tomography scan confirmed the diagnosis and the child underwent a direct laryngoscopy and rigid bronchoscopy (DLB) with laser excision of the lingual TGC and a TE.

Procedure

The surgical technique can be viewed separately as an Online Supplemental Video. The patient was induced to a spontaneous breathing but sedated with inhaled sevoflurane and intravenous propofol bolus, and subsequently maintained via administration of intravenous ketamine and propofol. A DLB was preformed which showed a large midline lingual thyroglossal cyst (TGC) in the vallecula and a posteriorly displaced epiglottis inverting over the glottic aperture (Figure 1). The child was then intubated with a 3.0 laser safe tube (Shiley; Covidien) and subsequently placed in suspension with a toddler Benjamin Lindholm laryngoscope (Karl Storz Endoscopy America, Inc) with the aid of a self-retaining laryngoscope holder secured to a Mayo stand. An operating microscope (Zeiss) set to laryngeal work focal length was then used to visualize the surgical field. The Lumenis Ultrapulse Duo flexible fiber CO2 laser (Lumenis Inc) was then brought into the field. Standard laser safety precautions were followed. The lingual TGC was grasped with an alligator microlaryngeal forceps, and the handheld laser was then used to dissect the cyst from the tongue and the lingual surface of the epiglottis. The cyst was removed en bloc while simultaneously de-mucosalizing the lingual surface of the epiglottis, and a TE was subsequently performed.

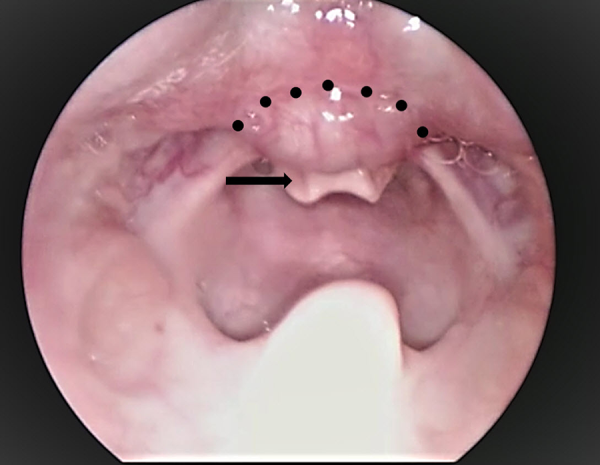

Figure 1

Direct laryngoscopic view showing the thyroglossal duct cyst with epiglottic prolapse. Dotted line shows the boundary of the cyst; black arrow, epiglottis.

For TE, the surface marking for needle placement was just above the hyoid. The neck was sterilely prepped and draped, and a 5 mm horizontal midline incision was made at the level of the hyoid and deepened to subcutaneous tissue to develop a pocket, wide enough to accommodate a 5-mm-diameter silicone disc (Bentec Medical Inc) to support suture knots. An 18-G needle with prethreaded 2-0 Prolene suture (Ethicon) loop just proximal to the bevel of the needle was inserted through the midline incision into the inferior vallecula and then through the epiglottis inferiorly in the midline, guided by endolaryngeal telescopic visualization. Once the needle location was confirmed endoluminally, the suture loop was advanced, grasped by alligator microlaryngeal forceps, and brought out through the laryngoscope. The needle was then removed from the suture such that the free ends of the looped suture were still present transcervically and secured with hemostats. Next, a 20-G needle loaded with a single 2-0 Prolene suture with one free end passed through the needle lumen and inserted through the neck passed over the hyoid and placed about half a centimeter superiorly to the previous stitch through the vallecula and the epiglottis. Once the needle was identified endoluminally, the suture was pushed through the needle. It was withdrawn superiorly with the grasper and taken out through the laryngoscope. A segment of suture was maintained exiting the neck at the puncture site. The needle was subsequently removed, and the sutures were secured with hemostats. The single Prolene suture was then threaded into the loop by the laryngoscopist while holding tension on the single suture with the surgeon at the neck pulling the loop. The looped suture is subsequently pulled through the neck. Once the loop exited the neck, the laryngoscopist released the single stitch, which was taken out the neck, leaving a single stitch precisely placed through the epiglottis. The free ends of the single stich in the neck were then secured over a custom trimmed 0.040-in silastic disc (Bentec Medical Inc) with two small puncture holes. The disc was placed within the wound pocket and the suture knot was tied onto the disc while observing the epiglottopexy endoscopically, without significantly distorting the epiglottis (Figure 2A-D).

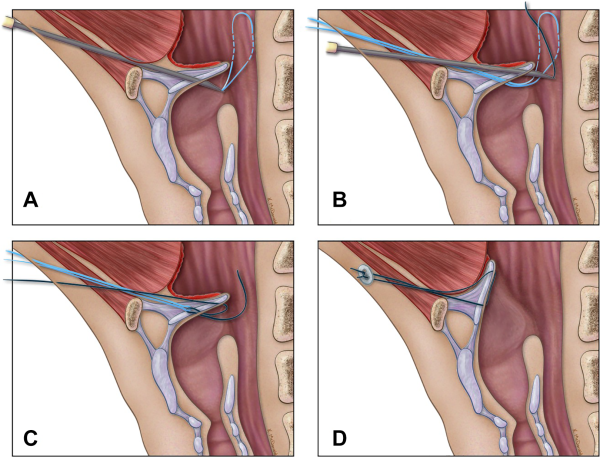

Figure 2

A, A schematic diagram showing needle placement. An 18-G needle with prethreaded 2-0 Prolene suture loop inserted through the midline incision into the inferior vallecula and then through the epiglottis inferiorly in the midline. B, Placement of the second 20-G needle loaded with a single 2-0 Prolene suture inserted through the neck and placed about half a centimeter superiorly to the previous stitch. The single suture is then threaded into the looped suture. C, The looped suture is then pulled through the neck drawing the single suture along with it resulting in placement of the stitch through the epiglottis. D, The suture is tied over a silastic disc with multiple knots.

The wound was closed with 4-0 Monocryl. Tightened aryepiglottic folds were then released bilaterally using the laser (Figure 3).

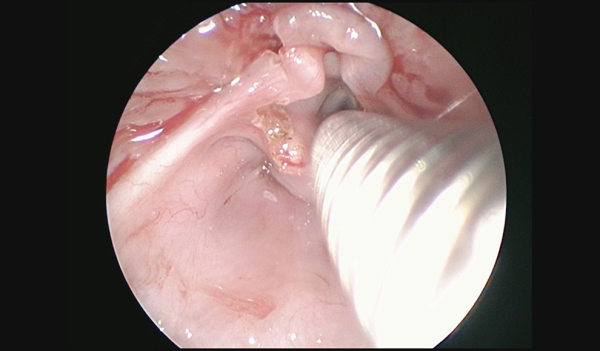

Figure 3

Direct laryngoscopic picture showing the completed epiglottopexy.

The laser safe tube was exchanged for 3.5 cuffed endotracheal tube, and the patient was monitored overnight in the pediatric intensive care unit with an uneventful extubation next day. A 4-month follow-up revealed maintenance of the epiglottopexy with no evidence of aspiration on a functional endoscopic swallow assessment.

Discussion

Even though various surgical approaches using an array of instruments have been described for EP in children, no study to date has demonstrated superiority of one technique over the other. The multitude of described techniques are a testimony to the technical difficulty in achieving a stable epiglottopexy especially in infants.- In the present article, we describe a technique of exo-endolaryngeal suturing using easily available instruments. The authors have used the technique in 2 other cases of EP associated with failure of decannulation after laryngotracheal reconstruction with optimal results. Even though the follow-up in these cases is limited, the maintenance of epiglottopexy even at 4 months in the present case is encouraging as most of them usually fail at the initial follow-up. There are some technical nuances to the technique which the authors would like to emphasize.

As far as aesthesia is concerned, even though in the present case a laser safe tube was used, the procedure can be achieved in an adequately sedated spontaneously breathing child. Correct midline laryngoscopic suspension is critical for surgical success and for avoidance of epiglottic distortion during the procedure. The author’s preference is to use the Benjamin-Lindholm laryngoscope as it provides wide exposure of the base of the tongue, vallecula, and the epiglottis. For TE, the laryngoscopic suspension is proximal as compared to the routine deep vallecular suspension undertaken for other supraglottic surgeries. Also, one size bigger laryngoscope, if possible to accommodate, is helpful in providing an optimal surgical field and an enhanced room to work the instruments. Preloading the needles with sutures and making sure that they can easily slide through the needles will ensure that the surgical procedure runs smoothly. The external puncture site is critical and is just above the hyoid, strictly in the midline. Even a slight paramedian positioning of the placement site can cause epiglottic distortion. For de-mucosalization of the lingual surface of the epiglottis and the base of the tongue, the author’s preference is to use the CO2 laser in ultrapulse mode as it provides control and precision while reducing the damage to the surrounding tissues. The mucosa of the tip of the epiglottis is preserved so that adequate laryngeal protection can be maintained. The placement through the epiglottis is important, with the inferior stitch being placed just above the base of the epiglottis and the superior stich 3 to 5 mm above the inferior stich. Tightening the suture can result in epiglottic distortion and as such the suture is kept loose. This also might prevent the stitch from cutting through the epiglottis. After the epiglottopexy, there is some tightening of the AE folds, which can be incised using wither laser or cold steel instruments to widen the airway. The suture is tightened over a silastic button to avoid cutting through the soft tissue and buried underneath the strap muscles to avoid extrusion and stitch abscess.

We describe a method of TE using easily available instruments. This method we believe can easily be adapted for any kind of EP. Long-term follow-up and larger series are required to establish the efficacy of this technique.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Sohit Paul Kanotra

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9510-5689

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Kantra SP, Givens VB, Keith B.Swallowing outcomes after pediatric epiglottopexy. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;277;285–291.

- 2. Ishman SL, Chang KW, Kennedy AA. Techniques for evaluation and management of tongue-base obstruction in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2018;26(6):409–416

- 3. Sandu K, Monnier P, Reinhard A, Gorostidi F. Endoscopic epiglottopexy using Lichtenberger’s needle carrier to avoid breakdown of repair. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(11):3385–3390

- 4. Whymark AD, Clement WA, Kubba H, Geddes NK. Laser epiglottopexy for laryngomalacia. Arch Otolaryngol Neck Surg. 2006;132(9):978–982.

- 5. Oomen KP, Modi VK. Epiglottopexy with and without lingual tonsillectomy. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(4):1019–1022.

- 6. Werner JA, Lippert BM, Dünne AA, Ankermann T, Folz BJ, Seyberth H. Epiglottopexy for the treatment of severe laryngomalacia. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2002;259(9):459–464. doi:10.1007/s00405-002-0477-7