Main Text

Kikuchi–Fujimoto disease (KFD) is a self-limited disease described by Japanese pathologists Kikuchi and Fujimoto in 1972. , This disease is more common in young Asian women. Patients often present with fever, and physical examination typically reveals cervical lymphadenopathy. The diagnosis of KFD is based mainly on lymph node biopsy. The treatment of KFD is primarily symptomatic, requiring only acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. The role of antibiotic therapy is unclear. Corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, or hydroxychloroquine are reserved for refractory or recurrent cases. KFD has a good prognosis, with most patients recovering fully; only a few patients relapse or develop systemic lupus erythematosus. -

Case 1

A 15-year-old Asian woman presented to our outpatient clinic with a 6-day fever. She experienced a sore throat and a slightly runny nose but denied cough and other respiratory symptoms. Physical examination revealed palpable and painful cervical lymph nodes in the right neck. Fiberoptic endoscopy showed erythematous mucosa in the upper aerodigestive tract. Neck sonography revealed reactive lymphadenopathy, with level I to level V nodes in the right neck (Figure 1A). The largest node was examined by core needle biopsy. A laboratory examination revealed leukopenia, thrombocytopenia, atypical lymphocytes, and band cells. The patient was hospitalized and was initially given ampicillin/sulbactam. Antipyretics were regularly administered. However, tests for Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, and atypical pathogens were performed because of persistent fever. Serological tests were positive for Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM and IgG (1:320×+). Therefore, we changed the antibiotic regimen to a clarithromycin regimen (1000 mg/d). The fever subsided 1 day after clarithromycin was administered. Histopathology findings of core needle biopsy revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis, compatible with KFD (Figure 2A and 2B). The patient was not given corticosteroids or hydroxychloroquine during the entire hospital stay. She was followed-up in the outpatient clinic for the next 2 years, during which neck sonography revealed that the lymph nodes gradually decreased and returned to their normal size. No recurrence of KFD was observed during the 2-year follow-up.

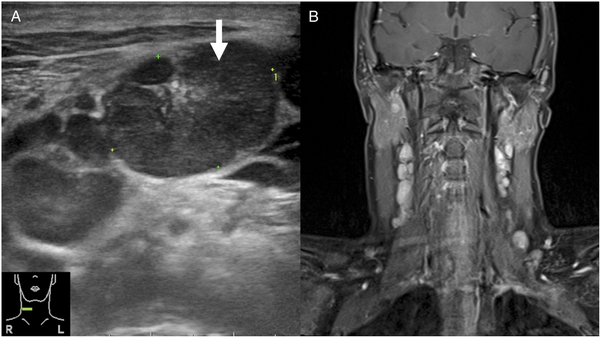

Figure 1

(A) The neck sonogram of case 1 shows multiple conglomerated lymph nodes in the right neck level III. The largest lymph node is marked with an arrow in the picture (21.5 × 14.9 mm2). The largest node displays a central echogenic hilum. (B) T1-weighted MR image with contrast in case 2 shows the bilateral neck lymphadenopathy extending from level II to level V.

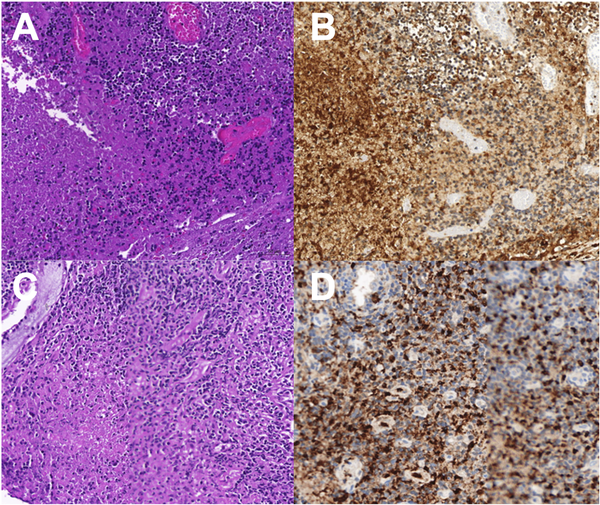

Figure 2

(A) Histopathological picture of case 1 shows coagulative necrotizing area mainly in the paracortical area (left side), with numerous histiocytes (right side) (Hematoxylin and eosin, 200×). (B) Histiocytes are highlighted by CD68 (200×). (C) The histopathological picture of case 2 shows focal areas of coagulative necrosis (Hematoxylin and eosin, 200×). (D) Histiocytes are highlighted by CD68 (400×).

Case 2

A 23-year-old female Caucasian exchange student presented to the emergency department with a 3-day fever. She complained of sore throat, bloody nasal discharge with nasal obstruction, and bilateral neck pain. Physical examination revealed bilateral palpable and painful cervical lymph nodes ranging from level I to level V. Laboratory examination revealed leukocytosis with lymphocyte predominance and the presence of atypical lymphocytes. Fiberoptic endoscopy showed enormous adenoid tissue with active inflammatory change and a bloody surface. MRI showed enlarged bilateral cervical lymph nodes (Figure 1B). Similar to what occurred in previous patient, the fever persisted after the patient had been hospitalized, and it could not be relieved by acetaminophen and ampicillin/sulbactam. Subsequently, the patient underwent adenoidectomy and an open biopsy of the cervical lymph node. Histopathology revealed necrotizing lymphadenitis (Figure 2C and 2D). KFD was diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and pathologic results. Because of our experience with previous patient, we quickly proceeded to investigate KFD-related pathogens, including Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Again, Mycoplasma pneumoniae IgM was confirmed. Therefore, we changed the antibiotic regimen to azithromycin (500 mg/d). The fever subsided 2 days after azithromycin had been administered. The patient was followed-up for 1 year, and no recurrence of KFD or development of SLE was observed.

Etiologies associated with KFD include the Epstein–Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, varicella–zoster virus, human herpesvirus, human immunodeficiency virus, Y. enterocolitica, and Toxoplasma. However, evidence that infection can directly cause KFD is lacking. Research has shown that CD8-mediated cytotoxicity, enhanced by histiocytes, can cause apoptotic cell death and may play a role in KFD. , In other words, KFD is a sequential histopathologic response of lymph nodes resulting from various initiating events. Only 2 cases of KFD triggered by Mycoplasma pneumoniae have been reported in the literature. , The detection of Mycoplasma IgM by serological tests indicates an acute stage of Mycoplasma infection, and antibiotics may impede the cell storm triggered by Mycoplasma pneumoniae. However, the role of antibiotics is still unclear in the treatment of KFD; nevertheless, our experience with KFD associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae suggests that administration of appropriate antibiotics is key to proper treatment. Both of our patients experienced fever for nearly 10 days before macrolides were administered. Once we started antibiotic treatment, the fever subsided within 2 days. Among the numerous etiologies of KFD, KFD associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae may respond well to antibiotic therapy.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Chiu-Ping Wang, Shu-Hwei Fan, Wei-Chun Chen, Uan-Shr Jan, and Wan-Ning Luo for their assistance in preparing this article. This article was edited by Wallace Academic Editing.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This study was supported by the Ministry of Science and Technology of the Republic of China (Taiwan) under grants MOST 109-2511-H-567-001-MY2, MOST 110-2511-H-567-001-MY2, and in part, funded by Cardinal Tien Hospital under grant CTH110A-2202. No additional external funding was received for this study.

References

- 1. Fujimoto Y, Kojima Y, Yamaguchi K. Cervical subacute necrotizing lymphadenitis: a new clinicopathologic entity. Naika. 1972;20:920–927. [in Japanese] .

- 2. Kikuchi M. Lymphadenitis showing focal reticulum cell hyperplasia with nuclear debris and phagocytes: a clinico-pathological study. Nippon Ketsueki Gakkai Zasshi. 1972;35:379–380. [in Japanese] .

- 3. Asano S, Akaike Y, Jinnouchi H, Muramatsu T, Wakasa H. Necrotizing lymphadenitis: a review of clinicopathological, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural studies. Hematol Oncol. 1990;8(5):251–260.

- 4. Kuo TT. Kikuchi’s disease (histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis). A clinicopathologic study of 79 cases with an analysis of histologic subtypes, immunohistology, and DNA ploidy. Am J Surg Pathol. 1995;19(7):798–809.

- 5. Kucukardali Y, Solmazgul E, Kunter E, Oncul O, Yildirim S, Kaplan M. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: analysis of 244 cases. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26(1):50–54.

- 6. Dumas G, Prendki V, Haroche J, et al. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease: retrospective study of 91 cases and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93(24):372–382.

- 7. Iguchi H, Sunami K, Yamane H, et al. Apoptotic cell death in Kikuchi's disease: a TEM study. Acta Otolaryngol Suppl. 1998;538:250–253.

- 8. Ohshima K, Shimazaki K, Kume T, Suzumiya J, Kanda M, Kikuchi M. Perforin and Fas pathways of cytotoxic T-cells in histiocytic necrotizing lymphadenitis. Histopathology. 1998;33(5):471–478.

- 9. Kim TY, Ha KS, Kim Y, Lee J, Lee K, Lee J. Characteristics of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease in children compared with adults. Eur J Pediatr. 2014;173(1):111–116.

- 10. Kim SH, Lee JM, Gu MJ, Ahn JY. A Case of Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease associated with mycoplasma pneumoniae infection. Clin Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2019;26(2):83–86.

- 11. Muller CSL, Vogt T, Becker SL. Kikuchi-Fujimoto disease triggered by systemic lupus erythematosus and mycoplasma pneumoniae infection-a report of a case and a review of the literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2021;43(3):202–208.