Introduction

External ear canal exostoses are usually bilateral and broad-based, secondary to external ear canal chronic cold exposure, especially water. They are mostly asymptomatic, but the obstruction of the external ear canal increases with their growth. Water and epidermal retention phenomena appear, leading to discomfort, hearing loss, or external ear infections. Prevention is based on the use of obturating plugs that prevent exposure to cold water, the main risk factor identified for this pathology.– Aspiration or local antibiotic therapy may be necessary in the case of local super-infection and surgery to prevent the recurrence of symptoms. Exostosis surgery, called canalplasty operations, was described in the second half of the 19th century. This surgery is difficult to learn due to the close proximity of external ear canal to nearby structures. Post-operative complications include meatal stenosis, prolonged healing, tympanic perforation, tinnitus, dizziness, sensorineural hearing loss, and damage to the facial nerve or temporomandibular articulation. Post-operative improvement of symptoms is observed in about 70% of cases. Surgical techniques evolved during the 20th century with the development of different techniques to reduce the morbidity of canalplasty.– However, the role of the surgeon’s experience had never been evaluated and the risk of recurrence was poorly known, with highly variable data depending on the studies., The main objective was to analyze the influence of the surgeon’s experience on the 3-year recurrence. Secondary objectives were to analyze the incidence of post-operative complications according to the surgeon’s experience, the incidence of recurrence and the influence of prolonged exposure to cold water on the incidence of recurrence.

Patients and Methods

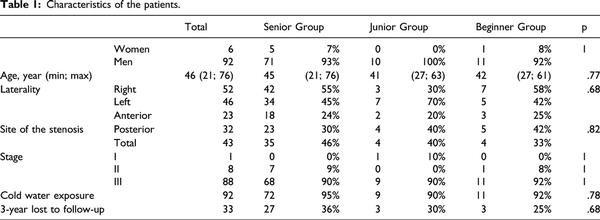

Ninety-eight canalplasty operations for exostoses of 77 patients (6 women and 71 men) were included from January 1, 2009 to August 1, 2016 in this retrospective monocentric study. The mean age was 49 ± 12 years. Post-operative consultations occurred at 1 week, 1 month, 6 months, and yearly. The mean follow-up time was 46 ± 37 months. Clinical recurrence was defined as a finding of restenosis of external ear canal at any stage. Symptomatic recurrence was defined as recurrence of symptoms related to exostoses (water or cerumen retention, hearing loss, and external ear infection). Overall recurrence included all events, clinical or symptomatic. Thirty-three ears (34%) were lost to follow-up before 3 years. The institutional ethics committee (29BRC19.02012) approved the study and all patients expressed their non-opposition to the use of anonymous data. This article followed the STROBE guidelines.

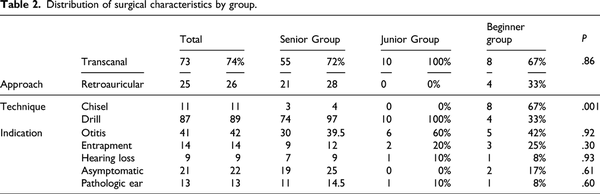

Nine different operators were identified. The seven Beginners operators (2 year’s experience) performed 12 operations (1–3 for each operator), the Junior operator (5 year’s experience) performed 10 operations (10%), and The Senior operator (15 year’s experience) performed 76 operations (78%). The included ears were separated into 3 groups, 1 group of novice surgeons, 1 for the junior surgeon, and 1 for the senior surgeon. Five categories of surgical indications were defined: “otitis” for external ear infection, “entrapment” for water or cerumen entrapment, “hearing loss” for conductive hearing loss due to obstruction, “asymptomatic” for exostoses preventing visualization of the tympanic membrane, “pathological ear” in case of middle ear surgery as the main surgical indication and having required a canalplasty for the approach. The surgical techniques (approach and instrumentation) were studied. All the operators performed a temporal fascia graft and silicone strips for 1 month. No skin grafting or stenting were used. Patients were asked to avoid exposure to cold water. The anatomic data of exostoses were defined, in the absence of a validated classification, by the stage of the stenosis. All patients had a CT-scan before surgery. A ≤30% stenosis defined stage I, between 31 and 60% defined stage II, and 61%≥ defined stage III. Delta bone conduction was defined as the difference in the mean bone conduction threshold measured in before and after surgery on the tonal audiogram at frequencies 250, 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. Conductive hearing loss (Delta Air Bone Gap) was defined by the difference of the air bone gap before and after surgery on the frequencies 250, 500, 1000, 2000, and 4000 Hz. Canalplasty on “ pathological ear” were excluded from the audiometric analysis, post-operative audiometric results depending on the procedure performed on the middle ear. Prolonged healing was defined as meatal stenosis, persistent local inflammation or bone exposure more than 6 weeks after canalplasty. Pain persistence at day 7 of the procedure was noted, as well as the occurrence of bleeding.

Three groups were compared, the Beginner, Junior, and Senior groups. Twelve ears were included in the Beginner group, 10 in the Junior group, and 76 in the Senior group. Tables 1 and 2 compared the main variables related to the ears operated on and the surgeons. The statistical comparison between these groups showed a difference in surgical technique. The use of micro-osteotome was more frequent in the Beginner group (67%) while the Junior and Senior groups preferred drilling (100% and 96%, respectively) (P = .002 and P < .001). The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate overall recurrence. An event was defined as a clinical or symptomatic recurrence of exostoses. The Log-Rank test was used to compare the recurrence rate according to groups. The analysis began by comparing the Senior and Beginner groups, then if significant (P ≤ .05), between the Senior and Junior groups, then if significant (P ≤ .05) between the Junior and Beginner groups. The ANOVA test could not be performed due to the small size of the group. The comparability of the group and the quantitative variables were analyzed with the Mann–Whitney U-test and the qualitative variables with the Fisher exact test. Significance was defined as P ≤ .05.

Results

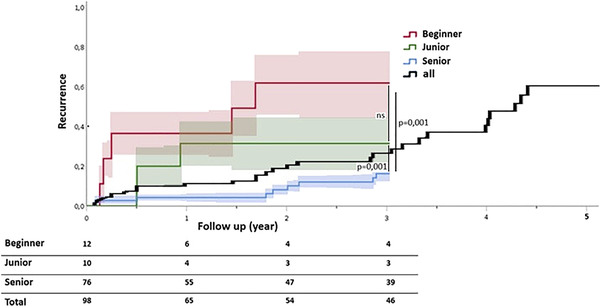

3-year overall recurrence was higher in the Beginner and Junior groups than in the Senior group, with rates of 69% CI95 (54%–84%), 38% CI95 (21%–55%), and 18% CI95 (9%–27%), respectively. The difference was significant between Beginner and Senior groups (P = .001), and between Junior and Senior groups (P = .001), but not significant between Beginner and Junior groups (P = .407) (Figure 1). Lost to follow-up ears were similar between groups: 3 ears (25%) in the Beginner group, 3 (30%) in the Junior group, and 27 ears (36%) in the Senior group (P = .757). The clinical and symptomatic recurrence rates were, respectively, 17% CI95 (5%–29%) and 50% CI95 (37%–63%) in the Beginner group, 10% CI95 (0%–19%) and 40% CI95 (39%–51%) in the Junior group, and 16% CI95 (7%–25%) and 8%, CI95 (0%–17%) in the Senior group. Recurrence occurred within a median of 8, 10, and 20 months for the Beginner, Junior, and Senior groups, respectively. Three recurrences within 6 months after surgery were observed in the Beginner group (25%), 2 in the Junior group (20%) vs 3 in the Senior group (4%). There was no difference in recurrence rate by stage of disease (stage 2: 10% CI95 [0%–31%] and stage 3: 18% IC95 [9%–36%], P = .194).

Figure 1

3-year overall recurrence in Beginner, Junior, and Senior groups, and 5-year overall recurrence.

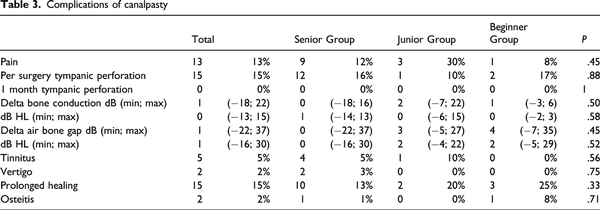

All post-operative complications are reported in Table 3. Perioperative perforation rates were 17% in the Beginner group, 10% in the Junior group, and 16% in the Senior group. All perforations were documented in the operative note and repaired at the time of surgery. All were closed at the post-operative consultation at 1 month. Prolonged healings were similar between the groups: 25%, 20%, and 13% for the Beginner, Junior, and Senior groups, respectively. An ear required a new canalplasty in the Beginner group (8%) and 1 in the Senior group (1%) (P = .27). The mean neurosensory and transmissive hearing variations were +4 dB, +3 dB, and +0 dB in the Beginner, Junior, and Senior groups, respectively. Extremes of hearing loss were observed in the Senior group. The maximum sensorineural hearing loss was −18 dB and was associated with vertigo. The maximum transmissive hearing loss was −22 dB. Two procedures were complicated by osteitis, which was diagnosed at 3 years of canalplasty in the Beginner group and 6 months in the Senior group. Both ears had required revision. The incidence of recurrence was linear and maximal during the first 5 years following the canalplasty with 97% of recurrences occurring within this period with an incidence rate of approximately 10% per year (Figure 1). Among these recurrences, exposure to cold water was continued in 48% of cases compared to 7% for ears without recurrence (P < .001, OR = 12.5 [4.4; 36.1]).

Discussion

Our study is the first to investigate the role of the surgeon’s experience on the recurrence occur of canalplasty for external ear canal exostoses. 3-year recurrence is higher in our series when the surgeon is a beginner or junior. This difference is probably the result of a more complete exostosis removal by the senior surgeon. Indeed, recurrences occurs earlier for beginner and junior operators with an average delay of 8 and 10 months. Nearly a quarter of these recurrences occurred within 6 months, probably reflecting the non-improvement of symptoms more than a real recurrence.

In studies evaluating surgical experience with type 1 tympanoplasty, most of the results suggest better outcomes for senior surgeons compared to residents, with a better myringoplasty graft rate., Baruah et al find that the learning curve is almost complete after 20 surgeries, in agreement with our study, with 10 surgery for the Junior operator. In endoscopic stapes surgery, the learning curve has also been studied, with similar functional results to those of microscopic surgery, with the same rate of complications., In Stapedotomy with a standardized laser-assisted surgical technique, Kwok et al found no difference between experienced and novice surgeons (58 vs 12 ears, respectively).

One limitation of this study is the difference in population size, with 76 ears in the senior group vs 10 in the junior group and 12 in the beginner group. The only significant difference between the groups was in surgical technique. Transcanal or retroauricular approach were used. Beginner operators used micro-osteotome more often than junior and senior operators, who preferred drilling. These preferences may have influenced long-term post-operative outcomes; however, the choice of technique was also a function of the operator’s experience. It is interesting to note that despite the use of drilling, the junior operator had a higher 3-year recurrence compared to the senior operator.

Drilling and chiseling are the 2 main techniques that have been described and studied since the beginning of canalplasty., Barrett et al and Hetzler recommend a combined approach combining osteotomy with impact scissors and drilling for a more complete procedure, reducing the risk of auditory complications related to drilling. It would be interesting to be able to observe the learning curve of the junior surgeon to know the number of canalplasties required to acquire this expertise. New techniques have been developed to reduce morbidity: the piezoelectric saw, which is used in maxillofacial surgery for its action on mineralized tissue to preserve soft tissue, could be used to reduce prolonged healing. In a series of 10 exostoses, Haidar et al. did not find any complication. This surgical technique would be interesting to evaluate over a larger series with long-term follow-up.

In our study, the complication rate is not modified by the surgeon’s experience. Fisher et al found a complication rate of 35% for surgeons in training and 21% for trained surgeons. The tympanic perforation rate of 15% in our study is comparable to the literature with rates ranging from 9.5% for Barrett et al to 22.5% for Hetzler The prolonged healing rate is 15%, comparable to the 18% rate found by Fisher and McManus, but higher than 4.7% in Grinblat et al. study. In a series of 254 exostoses treated by drilling, House and Wilkinson found a 4.8% risk of sensorineural hearing loss greater than 15 dB at 4000 Hz. Timofeev et al described sensorineural hearing loss after 3 canalplasties with a cumulative drilling time of 7 hours. In our series, excluding “pathological ears,” we find one case of sensorineural hearing loss with an average loss of 13 dB HL on the bone tonal curve at day 2 of a canalplasty performed by the senior operator. CT-scan showed the stapes dislocated into the vestibule. Five ears (5.1%) showed transient post-operative tinnitus that may be related to labyrinthic trauma.

The clinical recurrence rate was 14% at 36 months in our study, compared to 9% with an average follow-up of 24 months in the House and Wilkinson study. Timofeev et al reported symptomatic recurrence for most ears operated at 10 years, with a rate of 40% at 5 years. In our study, we have a symptomatic recurrence rate of 16% at 3 years. The lack of standardization in the definition of recurrence makes it difficult to compare studies. This high variability is also explained by the difficulties in long-term follow-up of these patients in good general condition with functional pathology. Only 24% of patients with symptomatic external ear canal exostoses consult according to the study by Lennon et al

Our study confirms the findings of Timofeev et al and Alexander et al that avoidance of cold water prevents recurrence. This preventive measure is widely known to the main exposed population. Indeed, 60–86% of surfers say they are informed, but only 24–54% of them wear stoppers., In our series, the rate of eviction from cold water reaches 80.6%, which can be explained by a cohort of ears already operated with greater awareness of this pathology. However, 52% of recurrences occur after stopping exposure. There could be a delayed effect of cold water exposure which would explain almost all recurrences in the 5 years post-operatively in our series. It would have been interesting to know the duration and frequency of cold water exposure prior to ear surgery in our cohort to evaluate whether the intensity of preoperative exposure influenced the recurrence delay after canaplasty.

Conclusion

This is the first study investigating the role of the surgeon’s experience on the risk of recurrence of canalplasty for external ear canal exostoses. The incidence of recurrence appears to decrease with surgeon experience above a certain threshold and with cessation of cold water exposure. We did not find any change in the rates of complication rates pre- and post-operatively according to surgeon experience.

Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Hurst W, Bailey M, Hurst B. Prevalence of external auditory canal exostoses in Australian surfboard riders. J Laryngol Otol. 2004;118:348–351.

- 2. Kroon DF, Lawson ML, Derkay CS, Hoffmann K, Mccook J. Surfer’s ear: External auditory exostoses are more prevalent in cold water surfers. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:499–504.

- 3. Attlmayr B, Smith IM. Prevalence of ‘surfer’s ear’ in Cornish surfers. J Laryngol Otol. 2015;129:440–444.

- 4. Mudry A, Hetzler D. Birth and evolution of chiselling and drilling techniques for removing ear canal exostoses. Otol Neurotol. 2016 Jan;37(1):109–114.

- 5. Hempel JM, Forell S, Krause E, Müller J, Braun T. Surgery for outer ear canal exostoses and osteomata: Focusing on patient benefit and health-related quality of life. Otol Neurotol. 2012;33:83–86.

- 6. Haidar YM, Ajose-Popoola O, Mahboubi H, Moshtaghi O, Ghavami Y, Lin HW, et al. The use of an ultrasonic serrated knife in transcanal excision of exostoses. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37:1418–1422.

- 7. Puttasiddaiah PM, Browning ST. Removal of external ear canal exostoses by piezo surgery: A novel technique. J Laryngol Otol. 2018;132:840–841.

- 8. Kozin ED, Remenschneider AK, Shah PV, Reardon E, Lee DJ. Endoscopic transcanal removal of symptomatic external auditory canal exostoses. Am J Otolaryngol. 2015;36:283–286.

- 9. House JW, Wilkinson EP. External auditory exostoses: Evaluation and treatment. Otolaryngology-Head Neck Surg (Tokyo). 2008;138:672–678.

- 10. Timofeev I, Notkina N, Smith IM. Exostoses of the external auditory canal: A long-term follow-up study of surgical treatment. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29:588–594.

- 11. Emir H, Ceylan K, Kizilkaya Z, Gocmen H, Uzunkulaoglu H, Samim E. Success is a matter of experience: Type 1 tympanoplasty : Influencing factors on type 1 tympanoplasty. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2007;264(6):595–599.

- 12. Onal K, Uguz MZ, Kazikdas KC, Gursoy ST, Gokce H. A multivariate analysis of otological, surgical and patient-related factors in determining success in myringoplasty. Clin Otolaryngol. 2005;30(2):115–120.

- 13. Baruah P, Lee JDE, Pickering C, de Wolf MJF, Coulson C. The learning curve for endoscopic tympanoplasties: A single-institution experience, in Birmingham, UK. J Laryngol Otol. 2020:134: 431–433.5

- 14. Lucidi D, Fernandez IJ, Botti C, Amorosa L, Alicandri-Ciufelli M, Villari D, et al. Does microscopic experience influence learning curve in endoscopic ear surgery? A multicentric study. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2021;48(1):50–56.

- 15. Monteiro EMR, Beckmann S, Pedrosa MM, Siggemann T, Morato SMA, Anschuetz L. Learning curve for endoscopic tympanoplasty type I: Comparison of endoscopic-native and microscopically-trained surgeons. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2021;278(7):2247–2252.

- 16. Kwok P, Gleich O, Dalles K, Mayr E, Jacob P, Strutz J. How to avoid a learning curve in stapedotomy: A standardized surgical technique. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38(7):931–937.

- 17. Grinblat G, Prasad SC, Sanna M. Transcanal approach with osteotomy versus retroauricular approach with microdrill for canaplasty in exostosis and osteomas. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38(5):784.

- 18. Ghavami Y, Bhatt J, Ziai K, Maducdoc MM, Djalilian HR. Transcanal micro-osteotome only technique for excision of exostoses. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(2):185–189.

- 19. Barrett G, Ronan N, Cowan E, Flanagan P. A long-term follow-up study of 92 exostectomy procedures in the UK: Exostoses: Drill or Chisel? Laryngoscope. 2015;125:453–456.

- 20. Hetzler DG. Osteotome technique for removal of symptomatic ear canal exostoses. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(S113):1–14.

- 21. Fisher EW, McManus TC. Surgery for external auditory canal exostoses and osteomata. J Laryngol Otol. 1994;108:106–110.

- 22. Grinblat G, Prasad SC, Piras G, He J, Taibah A, Russo A, et al. Outcomes of drill canalplasty in exostoses and osteoma: Analysis of 256 cases and literature review. Otol Neurotol. 2016;37(10):1565–1572.

- 23. Lennon P, Murphy C, Fennessy B, Hughes JP. Auditory canal exostoses in Irish surfers. Ir J Med Sci. 2016;185(1):183–187.

- 24. Alexander V, Lau A, Beaumont E, Hope A. The effects of surfing behaviour on the development of external auditory canal exostosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272:1643–1649.

- 25. Reddy VM, Abdelrahman T, Lau A, Flanagan PM. Surfers’ awareness of the preventability of ‘surfer’s ear’ and use of water precautions. J Laryngol Otol. 2011;125:551–553.

- 26. Nakanishi H, Tono T, Kawano H. Incidence of external auditory canal exostoses in competitive surfers in Japan. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;145:80–85.