Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a worldwide pandemic associated with more than 94 million infections and more than 2 million deaths., Respiratory and gastrointestinal symptoms were first described. These manifestations may be associated with severe forms of COVID-19 which can lead to death. Subsequently, loss of smell and taste were identified as specific symptoms of COVID-19. These are the most common ear, nose, and throat complaints, and they are usually found with mild-to-moderate forms. In the last few months, some papers pointed out a potential association between COVID-19 and the development of sudden sensorineural hearing loss (SSNHL), facial palsy, neck poly-adenopathy and parotitis.- In this article, we report a case of vestibular neuritis (VN) occurring in a child suffering from COVID-19 without other infectious causes.

Case Report

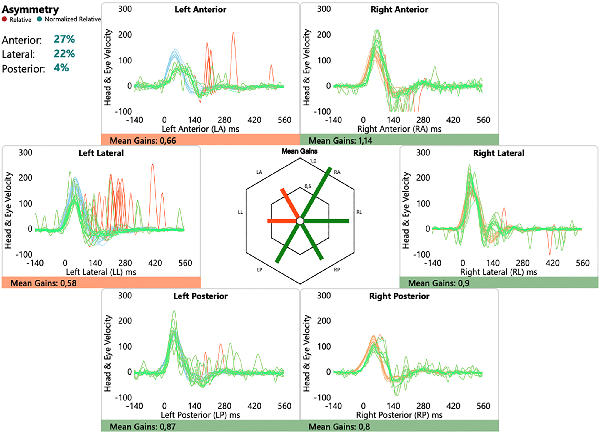

A 13-year-old girl presented to our Vertigo Clinic in November 2020 for sudden onset continuous rotatory vertigo and intractable vomiting without fever. The symptoms started in the morning. She never experienced vertigo before and she did not complain of hearing loss, otalgia, tinnitus, or headache. No dyspnea or smell disorder were mentioned. Medical history was unremarkable and she did not take any drugs. Physical examination revealed a right spontaneous horizonto-rotatory nystagmus (grade 3 according to the Alexander’s law) and a left deviation on Fukuda stepping test. No paresis or hypoesthesia of the limbs were identified. There was no hypo or hypermetry in the upper and lower limbs. Cranial nerves III, IV, V, VI, VII, XI, and XII were assessed and were symmetrical. Test of Skew was normal. Clinical horizontal head impulse test was positive for the left side. Otoscopy and auditory tests were normal (tympanometry and pure-tone audiometry). Video Head Impulse Test (vHIT) showed a decrease of the vestibulo-ocular reflex gain and catch-up saccades for the left anterior and lateral semi-circular canals (Figure 1). Thus, left superior vestibular neuritis was confirmed and vestibular rehabilitation was started. During the hospital stay, a nasal swab was carried out because her brother recently developed COVID-19. The presence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was confirmed. Four days later, the child was discharged. A quarantine was recommended and vestibular rehabilitation was carried on. The 1-month follow-up reported symptoms resolution and the SARS-CoV-2 serology was positive. Immunoglobulin G were also previously positive for the Herpes simplex virus (HSV) 1,2 and the Epstein-Barr Virus.

Figure 1

Assessment of the VOR gain of the 6 semi-circular canals by vHIT. The cupulogram (hexagon in the center of the figure) confirms a decrease in the VOR gain for the left anterior (LA) and lateral (LL) semi-circular canals. Head and eye velocity curves confirm the decrease in the VOR gain for these SCCs and demonstrate the presence of catch-up saccades (red spikes). LA SCC indicates left anterior semi-circular canal; LL SCCs, left lateral semi-circular canal; LP SCCs, left posterior semi-circular canal; RA SCCs, right anterior semi-circular canal; RL SCCs, right lateral semi-circular canal; RP SCCs, right posterior semi-circular canal; vHIT, video head impulse test; VOR, vestibulo-ocular reflex.

Discussion

Vestibular neuritis or acute unilateral peripheral vestibulopathy is an acute vestibular syndrome (AVS) which is characterized by a sudden onset of vertigo with nausea or vomiting, unsteady gait, head-motion intolerance, and spontaneous nystagmus lasting days to weeks. Vestibular neuritis is not associated with auditory deficits and a confirmation of a unilateral peripheral vestibular impairment with caloric test or vHIT is required. The pathophysiological mechanism would involve a reactivation of a latent herpes virus, most likely HSV-1 in the Scarpa ganglion or the vestibular labyrinth.

Through anosmia, agueusia, SSNHL and facial palsy, SARS-CoV-2 has proven his ability to induce nerve damage. Different hypotheses have been suggested to understand the means by which it can induce these lesions. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 cell entry depends on angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor and the transmembrane protease serine 2 (TMPRSS2). For instance, the presence of the ACE2 receptors and TMPRSS2 in the olfactory epithelium allows the entry of the virus and cause damage in the olfactory nerve and, secondary, anosmia. In mice, the receptors ACE2 and TMPRSS2 are also present in the Eustachian tube, the mucosal epithelium of the middle ear and in the inner ear. Thus, these receptors could act as a gate for the SARS-CoV-2 to enter into the vestibule and lead to VN. Secondly, as for Bell palsy associated to COVID-19, ischemia of the vasa nervorum and demyelination induced by the inflammatory process could be another way to generate VN. Lastly, several viruses have shown a trigger role for reactivation of HSV-1, explaining some cases of epidemic vertigo and rhinitis preceding the onset of vertigo. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 could be a good candidate.

Two cases of COVID-19-induced VN have been recently reported., Although the presence of SARS-CoV-2 was confirmed, none of these patients got a peripheral vestibular evaluation and so the diagnosis of VN remained uncertain. Indeed, confirmation of the peripheral origin of vertigo is essential to avoid missing out on a central disorder for which the brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can sometimes be normal. A recent study showed that neurological manifestations may affect up to 30% of patients with COVID-19. Among the neurological symptoms, balance disorders can affect 18% of patients with COVID-19. Of these, the majority reported simple dizziness, but acute vertigo attacks were present in 5%. In our case, the patient experienced an AVS. Head Impulse test, Nystagmus, Test of Skew (HINTS) examination allowed us to suspect a VN and vHIT confirmed the diagnosis of left superior vestibular neuritis. It is also interesting to note that this rare manifestation of COVID-19 affects a child for the first time.

Although systemic corticosteroids are usually recommended for the management of VN, we avoided them. Indeed, the World Health Organization discourages their use in case of mild forms of COVID-19 since they could increase by 3.9% the 28-day mortality in this group.

Finally, as for SSNHL and facial palsy, the association of VN with COVID-19 is only based on a temporal association and a plausible pathophysiology. Therefore, it is necessary to report additional cases of VN associated to COVID-19 in order to confirm the causality.

In case of VN, early detection of SARS-CoV-2 in this pandemic is required to prevent its spread.

Authors’ Note Written informed consent was obtained from a legally authorized representative for anonymized patient information to be published in this article.

Author Contributions QM and AN wrote the case report. QM and LL managed the patient. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Quentin Mat

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5545-6927

Carlos M. Chiesa-Estomba

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9454-9464

Jérôme R. Lechien

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0845-0845

References

- 1. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497–506.

- 2. World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) dashboard. Updated January 1, 2021. Accessed January 2, 2021. https://covid19.who.int/

- 3. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395(10229):1054–1062.

- 4. Lechien JR, Chiesa-Estomba CM, Place S, et al. Clinical and epidemiological characteristics of 1420 European patients with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Intern Med. 2020;288(3):335–344.

- 5. Saniasiaya J. Hearing loss in SARS-CoV-2: what do we know? Ear Nose Throat J. 2020. doi:10.1177/0145561320946902

- 6. Lima MA, Silva MTT, Soares CN, et al. Peripheral facial nerve palsy associated with COVID-19. J Neurovirol. 2020;26(6):941–944.

- 7. Lechien JR, Chetrit A, Chekkoury-Idrissi Y, et al. Parotitis-like symptoms associated with COVID-19, France, March-April 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(9):2270–2271.

- 8. Distinguin L, Ammar A, Lechien JR, et al. MRI of patients infected with COVID-19 revealed cervical lymphadenopathy. Ear Nose Throat J. 2021;100(1):26–28.

- 9. Kattah JC, Talkad AV, Wang DZ, Hsieh YH, Newman-Toker DE. HINTS to diagnose stroke in the acute vestibular syndrome: three-step bedside oculomotor examination more sensitive than early MRI diffusion-weighted imaging. Stroke. 2009;40(11):3504–3510.

- 10. Hegemann SCA, Wenzel A. Diagnosis and treatment of vestibular neuritis/neuronitis or peripheral vestibulopathy (PVP)? open questions and possible answers. Otol Neurotol. 2017;38(5):626–631.

- 11. Ahmad I, Rathore FA. Neurological manifestations and complications of COVID-19: a literature review. J Clin Neurosci. 2020;77:8–12.

- 12. Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, et al. SARS-CoV- 2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280. e8.

- 13. Sungnak W, Huang N, Bécavin C, et al. SARS-CoV-2 entry factors are highly expressed in nasal epithelial cells together with innate immune genes. Nat Med. 2020;26(5):681–687.

- 14. Uranaka T, Kashio A, Ueha R, et al. Expression of ACE2, TMPRSS2, and Furin in mouse ear tissue, and the implications for SARS-CoV-2 infection. Laryngoscope. 2020. doi:10.1002/lary.29324

- 15. Zhang W, Xu L, Luo T, Wu F, Zhao B, Li X. The etiology of Bell’s palsy: a review. J Neurol. 2020;267(7):1896–1905.

- 16. Malayala SV, Raza A. A case of COVID-19-induced vestibular neuritis. Cureus. 2020;12(6):e8918.

- 17. Vanaparthy R, Malayala SV, Balla M. COVID-19-induced vestibular neuritis, hemi-facial spasms and Raynaud’s phenomenon: a case report. Cureus. 2020;12(11):e11752.

- 18. Viola P, Ralli M, Pisani D, et al. Tinnitus and equilibrium disorders in COVID-19 patient: preliminary results. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;23:1–6.

- 19. RECOVERY Collaborative Group; Horby P, Lim WS, et al. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19 - preliminary report. N Engl J Med. 2020. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021436