Contribution to Health Promotion

Cultural determinants of health play a significant role in shaping individuals’ health beliefs and behaviours around drowning risk.

Applying the theory of planned behaviour (TPB) enables deeper insights into the awareness, attitudes and knowledge of water safety among adult migrants, which can inform culturally tailored interventions, promote safer behaviours and motivate migrants to learn to swim.

Water safety and swimming education should be incorporated within comprehensive multisectoral settlement support strategies to ensure migrants can purse aquatic activities safely in their new communities.

Contextualized and inclusive approaches to drowning prevention are needed to effectively reduce drowning inequities.

INTRODUCTION

Migrants are at significant risk of drowning (, , , , ), however, are often not considered in drowning prevention research and programmes. Drowning prevention is a complex public health challenge accounting for over 300 000 fatalities globally, and is influenced by shifting population trends, the impact of climate change and disaster, and limited access to safe places to swim (, , ). This number is likely an underestimation as it excludes deaths due to water transport incidents, disaster-related, or unsafe sea migration. Since 2014, an estimated 40 600 refugee and migrants have drowned in transit while crossing waterbodies ().

Significant inequities exist, with the burden of drowning most concentrated in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) (, , , ). Populations most vulnerable to drowning across all countries include migrants, young children (0–4 years), young males, and First Nations peoples (). In high-income countries (HIC), disparities in drowning fatalities are evident, particularly among minority populations, including migrants (, ) In the Netherlands, migrants from non-Western backgrounds have a significantly higher incidence rate of unintentional drowning compared to people with a native Dutch background (). Similarly in Sweden, people from non-Swedish origins were found to be at high-risk of drowning than people of Swedish origin (). In Australia, migrants from specific countries (e.g. South Korea, Taiwan, and Nepal) had higher rates of drowning per residential population compared to Australian-born ().

Universal factors that influence drowning risk of individual's include inadequate swimming and water safety skills, a lack of knowledge, unsafe attitudes, and behaviour around the water (, ), not wearing a lifejacket when boating and fishing (, ), consuming alcohol and drugs around water and, swimming in unsupervised locations (, ). Behaviour change models can help explain the underlying factors influencing people's intention and actions related to risky behaviour. The theory of planned behaviour (TPB) (), the Health Belief Model (), the Protection Motivation Theory (), and the integrative model of behavioural prediction () have all been applied in drowning prevention research to identify, explore and explain knowledge, attitudes and behaviour. This includes exploring drowning risk behaviours among teenagers (, ), risky practices when rock fishing (), parents motivation for enrolling children into swimming lessons (), individual's motivations for driving through floodwater (), and designing water safety for culturally diverse families ().

Inequities in drowning go beyond behavioural risk factors, and are influenced by social determinants of health, being the ‘non-medical factors that influence health outcomes, conditions in which people are born, grown, work, live and age’ (). These also encompass cultural and commercial determinants of health. Consequently, researchers, policymakers and practitioners recognize the complex intersectionality contributing to drowning risk (, ). This includes current and historical social determinants [such as systemic racism and discrimination (, )] and environmental factors [such as climate change, disasters and extreme weather-related drowning (, )]. Economic, political, and cultural contexts play a role, including voluntary immigration between countries, and displacement caused by global conflict (). This necessitates population-level policy and systemic changes to be made, as recognized by the WHO (, ), and the United Nations Resolution for drowning prevention ().

Cultural factors, and broader determinants of health, contribute to shaping individuals’ health beliefs and behaviours () and may play a role in drowning risk. Within some societies, cultural beliefs exist where a drowning is considered ‘fatalistic’ or ‘God's wish’ (), with little awareness of prevention measures. Studies from the Sundarbans region of India () and West Nusa Tenggara Province, Indonesia (), reported that cultural belief systems continue to prevent people seeking help during a drowning incident, with traditional methods such as spinning the victim still common practice preventing children from receiving appropriate help to aid survival (, ). Other cultures pass on stories featuring ghosts, monsters, or mythical creatures to scare children from going into the water, which may negatively impact participation, contributing to intergenerational fear into adulthood (, , ).

There is a growing body of research exploring water safety knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour among migrants (and other ‘high-risk’ populations) in HIC (, ). However, this research is predominately from Australia, New Zealand (NZ), and the United States (US), and of quantitative design, using self-reported surveys. Australian studies reported low levels of beach safety knowledge (, ); unsafe practices for young children around water (), and risky behaviours when rock fishing (). In NZ, studies report increased aquatic participation despite a high proportion reporting inadequate levels of water safety knowledge and swimming skills ().

Australia's population is culturally diverse, with ∼50% of the population either born overseas, or having at least one parent born overseas (). Over the last two decades, the fastest growing migrant populations in Australia are from the Asian region, marking a shift from earlier migration trends from the United Kingdom (UK), Europe, and NZ (). In Australia, the Australian Water Safety Strategy 2030 recognizes that drowning disproportionately affects particular populations including First Nations people, migrant communities, older people, and those living in regional locations, calling for targeted drowning prevention efforts (). Migrants account for 34% of fatal drowning in Australia, with drowning risk factors including length of time in Australia, low levels of water safety knowledge, and inadequate swimming skills (, ). Differences in drowning trends have been observed between migrants and Australian-born individuals, particularly in the locations visited and activities being undertaken prior to drowning ().

This study aimed to explore factors influencing water safety and drowning risk among Australian migrants to inform culturally appropriate and relevant drowning prevention policies and practices.

METHODS

Study design

An exploratory, qualitative study design was conducted using semi-structured interviews and focus groups to gain in-depth perspectives from the chosen study population. A deductive approach was applied to inform the design of questions in this qualitative study, described as ‘a structured approach to enrich your understanding of qualitative data through the lens of established theories’ (), guided by the TPB ().

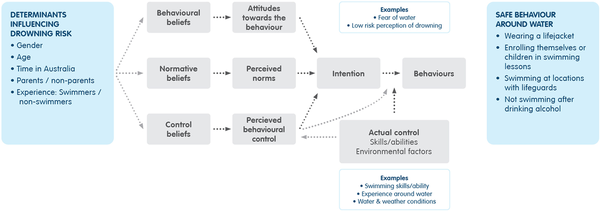

The TBP proposes that an individual's behaviour is influenced by attitudes, subjective norms and perceived behavioural control, which in turn, informs the intention to perform a certain behaviour (). This model has been used widely to predict a range of health behaviours, including healthy eating and nutrition (), oral hygiene (), and most recently for predicting uptake of the Covid-19 vaccination (). The TPB was used to understand people's influencing factors towards drowning risk (age, gender, cultural background, experiences, and swimming ability). In a drowning context, behavioural beliefs inform attitudes towards the behaviour, e.g. a person may believe that they do not need a lifejacket while boating, due to their past experiences, perceived skills, and confidence that nothing will go wrong. Normative beliefs inform perceived norms, e.g. in some cultures swimming is not a popular leisure activity, and learning to swim may not be seen as important. Control beliefs inform perceived behavioural control which in turn influences behavioural intentions, e.g. males overestimating their swimming ability and underestimating the risk of drowning leading them to swim, at unsupervised locations, at night or after consuming alcohol. Actual control could be influenced by swimming skills, experience around water, the environmental conditions (water and weather conditions), and if there are lifeguards present or not (Fig. 1). These domains were used to prompt the interview questions (Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1

Modified TPB to explore knowledge, attitudes and behaviour towards drowning risk among adult migrants in Australia ().

Terms and definitions

This study uses the term ‘migrants’. For this study, this included adults ≥18 years from a migrant background (i.e. not born in Australia), who were residing in Australia at the time of the study for any purpose; people born in Australia of migrant parents; international students; and people from refugee backgrounds. Visa status was not asked for, nor a requirement to be included in this study. Country of birth and length of time were asked to gain background information and establish rapport between the leader researcher and participants. Participants could choose not to answer this question.

Participants and selection criteria

A purposive sampling approach () was used to recruit migrant adults (≥18 years) between May and December 2021 who (i) had attended a learn-to-swim program in adulthood (‘new swimmers’) or (ii) could not swim (‘non-swimmers’) but had visited an aquatic environment within the last 12 months. The Australian capital cities of Sydney in New South Wales (NSW); Brisbane in Queensland; Peth in Western Australia (WA); and Melbourne in Victoria, were chosen for the study to reflect the locations with the largest migrant populations (), These cities are also where migrant drowning incidents most commonly occur ().

Focus group (FG) and interview participants were recruited through adult learn-to-swim programmes or from English language programmes. The lead researcher (SW-P) initially approached swim program managers, swim teachers and English language program teachers, who then discussed the study with their participants, accounting for varying levels of English language proficiency (in some cases an interpreter assisted in providing greater clarification). Information flyers about the study were distributed to potential participants in English only. FGs were scheduled to take place during their usual program timetable, for participant convenience, in coordination with program managers and teachers. Swim program managers and teachers were not present during the focus groups.

Data collection

Interview questions were developed, then piloted for a previous qualitative study which explored migrant women learning to swim in Australia (, ). Questions were then adjusted for this current study to include people not engaged in swimming lessons (Supplementary File S1). The development of the questions was guided by the domains of the TPB (Fig. 1). Methodology followed the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research tool (Supplementary File S2) to improve the quality and enhance the rigour of qualitative research ().

The data collection of the study was intended to be face-to-face FGs across Australia. However, soon after the initial FGs took place in May and June 2021, the second phase of Covid-19 social and travel restrictions occurred in Australia and the rest of the study data collection had to take place via online interviews, as described below. The lead researcher (SW-P) lead in-person FGs and interviews in Brisbane, Queensland and in Perth, WA, in May and June 2021. The FGs in Brisbane were conducted in English during English language classes, as guided by the head teacher; with other participants/peers acting as interpreters when required. The researchers noted that while the use of peers as interpreters may have introduced a bias, at the same time, it was important for participants to feel comfortable to share their experiences and perspectives, and they may not have been as forthcoming to share with a stranger or an official interpreter. In Perth, FG participants did not require translation due to a high level of English language comprehension of participants. Due to Covid-19 travel restrictions across Australia from mid-June 2021, after the Perth FGs had taken place, the remainder of the study with participants based in NSW and Victoria was conducted online or phone interviews (via Zoom or Microsoft Teams). All interviews were conducted by the lead researcher (SW-P) and did not require translation.

Analysis

While the FGs were conducted face-to-face, and the interviews conducted online, all data coding and analysis were handled the same way. All FGs and interviews lasted between 30 and 60 min, were audio recorded, and transcribed verbatim using the Otter.ai translation service. The first author (S.W-P.) checked all the transcripts separately for accuracy and undertook the initial coding from each transcript using NVivo V12. Data from both the interviews and FGs were thematically analysed using Braun and Clark's six-stage approach using a deductive approach utilizing the TPB, while also allowing for inductive analysis (). Researchers (R.C.F. and S.D.) also reviewed the transcripts and coded for similar themes. Final themes were reviewed and agreed upon by the entire research team (S.W-P., R.C.F., and S.D.). The lead author coordinated member checking with participants to check accuracy and correct interpretation of data via email. Several participants did not respond to the email; therefore, not all participants provided feedback which may be a limitation to the study.

Research team and positionality

The research team included a female PhD student (lead author S.W-P.) with a background in drowning prevention research, employed by a lead water safety agency in Australia, who has a migrant background from an English-speaking, HIC country, along with two senior Australian university academics. The potential for bias and power imbalances between some participants and the researchers is recognized. To address this, efforts were made from the outset to include diverse voices across a range of genders, age, cultures, religions, time in Australia, parents and non-parents, ensuring a broad range of perspectives were reflected in the study findings. Throughout the data analysis phase, the research team members were constantly checking and reflecting on their positionality, privilege and potential biases.

Ethics

All participants provided written and verbal informed consent prior to taking part in the study. Where required, information was interpreted in the FGs by other participants, or an English teacher (in the Brisbane FGs only) to ensure that all participants understood and provided informed consent to participate in the study, to be audio recorded and quotes used for research and publication purposes. All results are presented using anonymous quotes with gender, country of origin and years in Australia noted, e.g.: ‘male, India, 5 YIA’. At no stage are study participants identified. Ethics approval was granted by the James Cook University Human Research Ethics Committee (H7945).

RESULTS

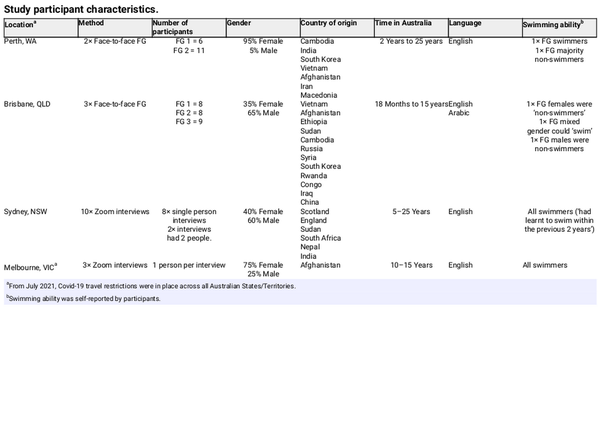

Fifty-seven participants from five FGs (n = 42) and 13 interviews (n = 15) were included in the study (Table 1). Over half were female (54%), with residential time in Australia ranging between 18 months and 25 years plus, with 19 countries represented (Table 1).

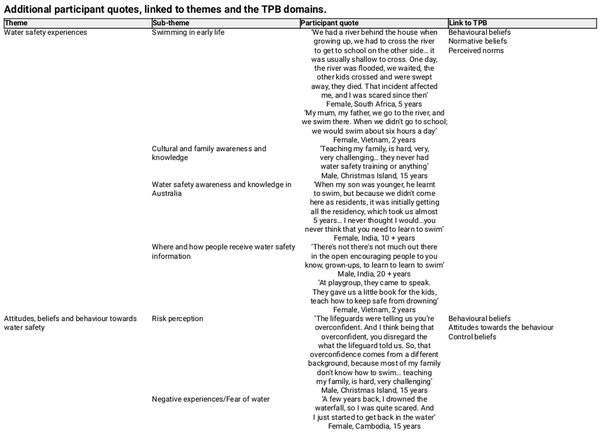

Data analysis highlighted four thematic areas that are presented as follows, with participant quotes, aligned to the TPB domains: (i) water safety experiences; (ii) attitudes, beliefs, and behaviour towards water safety; (iii) motivations and barriers to learning to swim; and (iv) benefits of learning to swim and fifteen subthemes (Fig. 2). Further participant quotes are presented in Table 2.

Figure 2

Thematic areas, themes and subthemes aligned to the TPB.

Water safety experiences

This theme explores participants’ lifelong experiences related to water and examines how these experiences influence current water safety awareness. This is explored through four subthemes (i) Swimming experiences in early life, (ii) Cultural and family awareness and knowledge, (iii) Water safety awareness and knowledge in Australia, and (iv) Where and how people receive water safety information.

Swimming in early life

Participants’ awareness of water safety and swimming was shaped by their experiences prior to migrating. Many recalled swimming in childhood, including formal lessons at school, informal instruction, or being self-taught. Those who attended lessons in school, described the training as basic, with little opportunity to continue swimming afterwards. One participant commented that public schools in her country lacked swimming pools, which were considered a luxury. Others recalled their daily experiences with local rivers, such as, crossing them to reach school or playing unsupervised with other children.

Cultural and family awareness and knowledge

Stories passed down through generations were common, used as a way to instil respect and fear, and to keep children away from the water. Participants recollected stories from their parents about water bodies, involving ghosts, monsters, or people drowning.

Before I came here, I never go in the water. Because I’m scared. My father and my mother they say when you go in the water you can die. (Female, Sudan, 5 YIA)

Water safety knowledge in Australia

Before migrating, most participants had limited awareness of water safety. However, they recognized the importance of their children learning to swim while growing up in Australia.

I didn't realize the importance of learning swimming; how important it is in Australian culture. When kids started school, they go to swimming then I realize, that's a life skill. In Australia it's as important as you learn cooking or communication skills. (Female, Nepal, 14 YIA)

Generally, participants were aware of the beach flags and lifeguards as indicators of safe places at the beach and understood the importance of watching children around water. There was less awareness towards safety when boating and fishing.

Where and how people receive water safety information from

Participants generally reported limited availability of water safety information. For those that had received water safety or swimming information, it was typically through word of mouth, English language classes or flyers at shops. Most participants did not recall water safety information provided from their general practitioner or other health provider. The exception was several mothers who received bath safety information when their children were born. Suggested avenues for disseminating information to communities were through places of worship, language classes, citizenship ceremonies, local government activities, migrant resource centres, student orientations, and migration agencies.

Attitudes, beliefs and behaviour towards water safety

This theme explores attitudes and behaviours, regardless of swimming ability, around the water, including the following concepts (i) risk perception, (ii) negative experiences (including a fear of water), (3) cultural/religious perspectives, and (4) stigma of being unable to swim.

Risk perception

Some participants were aware of their swimming limitations in the water and of the potential dangers, leading them to actively avoid water. Participants reported basic understanding that different aquatic environments, such as swimming pools, beaches, and rivers, presented varying levels of risks. Perceptions of water-related risks varied between males and female participants, with females generally being more cautious and aware of their limitations compared to males.

I love to swim in the sea, but I don't want to put myself in danger, because I’m not a good swimmer so I know my life is in danger…. (Female, China, 4 YIA)

One participant perceived that drowning risks within his community were influenced by prior experiences around rivers in their home country. He described that people, particularly males, were often unprepared for Australian water conditions, which he felt may have contributed to recent drowning fatalities within his community in Australia.

People used to go to that river and have done swimming in the lake [in Nepal] …so they think that what I have done over in Nepal, it is the same, but they don't understand the depth and how the water is flowing in Australia, so that is the reason we [Nepalese people] are having all those accidents in the Australian rivers. (Male, Nepal, 14 YIA)

Negative experiences (including a fear of water)

Negative experiences in the water included a fear of water, having a ‘near drowning’ experience, and being caught in a rip current at the beach. For others, a fear of water stemmed from childhood experiences, from either experiencing a negative incident themselves or witnessing one, such as a person drowning.

Several male participants recalled events with their friends, shortly after arriving in Australia which resulted in potentially life-threatening situations.

This was back in 2015. I wanted to go for a swim with my mates, but I wasn't good at swimming, I didn't know how to swim. So, I joined them to go swimming at the beach, and I nearly drowned. It was a close call. (Male, Afghanistan, 6 YIA)

One male participant recalled swimming at a beach and being caught in a rip current, and not realizing he was in trouble at the time. This experience impacted future participation in the ocean, describing the incidents as:

Was one of the most frightening things in my life and I was doing all the things I now know what not to do. (Male, England, 10 YIA)

Cultural and religious perspectives

Participants commonly perceived that swimming or engaging in water-based leisure activities was not part of their family or community norms, regardless of cultural or religious background. Several participants from HIC stated they were not exposed to water during family holidays, and swimming activity or going to pools was not a popular pastime.

Several participants described that in their culture, water is considered sacred or holy, with rituals performed in the water from birth to death, such as cremation sites along the river. These rituals were continued after migrating to Australia, reinforcing the ongoing cultural and religious significance of water. Drowning risk was not considered when performing these rituals.

The cultural connection is really important…our every ritual is related to water…from birth to death, different rituals throughout the lifespan are related to water. (Male, Nepal, 15+ YIA)

Stigma of being unable to swim

Both males and females reported feeling embarrassed to admit they were unable swim, and as a result still went into the water.

When you’re that bad at something it's embarrassing as an adult and to be vulnerable in the water with strangers, a little embarrassing. (Male, England, 10 YIA)

For some, there was an element of peer pressure to participate, despite their lack of swimming ability.

Embarrassed I couldn't swim but told my friends I could. I got pulled into the pool by my friends at a party and went straight to the bottom…I managed to get myself out. (Female, South Africa, 5 YIA)

Learning to swim

This theme describes influences on migrants participation in swimming and water safety programmes (swimming programmes), including barriers (fear, accessibility), experiences of learning to swim in adulthood (negative and positive), and the motivation for learning to swim.

Barriers to learning to swim

Participants described barriers to engaging in swimming programmes which differed among individuals. Despite a desire to learn to swim, a common perception was that it was ‘Impossible to learn to swim as an adult’. This belief was often described as a psychological barrier, such as a phobia of water, rather than a tangible one. Some felt swimming programmes were expensive and some parents expressed the challenges of attending due to childcare responsibilities. For young men who were studying and working, barriers included programmes not available outside of working hours, and venues being difficult to access on public transport. These logistical barriers outweighed the cost, with many stating they would be happy to pay for lessons.

Learning to swim as an adult

Several participants recalled their attempts to learn swimming from family or friends, often having a negative experience, or being frustrated that they could not progress quickly.

I remember [my wife] trying to teach me how to float in water. And I couldnt do it. I remember thinking then, all these kind of failed attempts would just compound this. I'm no good at this activity. It's just not going to be something that I can do. (Male, Scotland, 15 YIA)

Many of the ‘new swimmers’ in this study attributed their success to finding the right program and instructors who made them feel comfortable, helping to overcome their fear and making the experience enjoyable. Being relatable, building a trusting relationship and taking a tailored approach were seen as pivotal for creating a positive learning to swim experience.

It really depends on individual's style of teaching. With [instructor], it wasn't about trying to get us to compete or reach that level, it was the psychological part of it as much as the actual, swimming ability. I think having a right kind of teaching approach makes a huge difference. (Male, India, 20+ YIA)

In contrast, one person described their initial lessons as being a ‘tick box’ exercise for the instructor who did not take the time to understand their needs. This resulted in them not wanting to continue.

I did a few [lessons] as soon as I got here. I think the approach from teachers at the time… I felt that they were really just ticking the boxes and wanted the lessons to be done and over with. (Male, India, 15+ YIA)

Several participants explained that overcoming their fear of water was helped by learning skills to help themselves in the water, such as how to float, and not panic. This helped them feel more confident and in control.

I'm a learner, but now I have a confidence that if something happens, I am able to [float] until I get help…so I have couple of skills, I learnt how to breathe underwater, so that gives me confidence…. (Male, Nepal, 15 YIA)

Motivation

Motivation for learning to swim came from a range of factors, including previous negative experiences, encouragement from seeing other adults learn, and for many, a desire to protect their children.

One participant described a life-threatening experience in the ocean with his wife that motivated them to start swimming lessons.

My wife and I got caught out in the ocean, it was about 7-8pm…having no knowledge about the waves, being two young idiots, going as deep as we could trying to get the biggest wave and next thing, the wave just got so high, we couldn't touch the floor. This is before we started swimming properly. There was a surfer who we waved to, he put our hands onto his surfboard…I’ll remember the guy the rest of my life. So that was one of the encouragements. (Male, India 20+ YIA)

For parents, motivation for learning to swim often came from the realization that they were unable to help their children if they got into difficulty.

When I took my daughter to the swimming lesson…I'm in the pool, just observing her and if something happened, I can't help her…The lifeguard told me that she needs to be supervised by an adult…and then if something happened, I have to save her, so I realized that I also have to learn, that really motivated me to learn swimming. (Male, Nepal, 15 YIA)

Benefits of learning to swim

This theme highlights the benefits of learning to swim, ranging from physical and mental health benefits, social inclusion and new opportunities to participate in Australian culture, described in the following subthemes (i) finding joy in swimming, (ii) inclusion into the Australian community/culture, (iii) ongoing participation in aquatic activities, (iv) health and wellbeing.

Finding joy in swimming

After overcoming a fear of water, several participants described their joy in being able to swim and almost a disbelief that they had learnt to swim. Participants expressed that they believed they would never have had the opportunity to learn to swim, and discover the all the new things they can participate in.

[I had the] Most beautiful experience…Just didn't believe it would happen, did not believe in it. Biggest thing ever for me learning to swim…Very special thing to me, nothing has given me more joy…I’m a new person, it's turned around my life…For me it's been a blessing. (Male, India, 20+ YIA)

Inclusion into the Australia community/culture

Participants from all backgrounds, strongly perceived that swimming is a core part of the Australian culture and a healthy lifestyle, and saw being able to swim as a way to fit into their new community.

Swimming in Australia is part of DNA, it's just what you do and is part of the lifestyle. (Male, Scotland, 15 YIA)

Being unable to swim was considered a barrier to participating in social and recreational activities. This was illustrated by one participant who reflected on missing out on activities with her new friends because she was scared and unable to swim.

I can't swim so didn't even bother going in the water here in Australia…Interested in surfing but can't swim…Friends have a jet ski, but don't go because can't swim and scared even with a lifejacket. (Female, South Africa, 5 YIA)

Ongoing participation in aquatic activities

Participants expressed the desire to pursue other aquatic activities after learning to swim, including kayaking, snorkelling and ocean swimming, becoming a volunteer lifesaver or simply being able to join their family in the water.

Two participants stated that being unable to swim had been a frustrating barrier to doing triathlons, something they really wanted to engage in. One participant shared that after learning to swim just two years previously, they had progressed from short distance triathlons to half ironman distance, giving them immense satisfaction. Another participant described that as a result of learning to swim, they were considering doing their Bronze Medallion and becoming a volunteer lifesaver, something they had never considered previously.

Health and wellbeing

Participants attributed swimming as being beneficial to their physical and mental health and wellbeing and contributing to a healthy lifestyle. They perceived health benefits from swimming better than other exercise; with one participant stating that:

Swimming is the best exercise better than going to the gym I feel, because you are moving all muscles from your body from your head to toes, every muscle…It has different benefits. I prefer swimming than going to the gym because for me it is more beneficial. (Female, Nepal 14 YIA)

Others talked about swimming and the water as being a peaceful and relaxing activity for them.

It was like going in Himalayas in the Indian subcontinent to attain peace and quiet. For me now, going to the water is my Himalayas. (Male, India, 15 YIA)

DISCUSSION

This study identified factors influencing drowning risk for migrant adults in Australia including limited exposure to the water prior to migrating, a lack of water safety knowledge and skills, influenced by their behavioural, normative, and control beliefs, including cultural norms and life experiences. As such, migrants require targeted strategies (, , , ).

This study highlights the complexity of people's relationship with water, encompassing cultural perspectives, equity issues, everyday interactions with water, fear, joy, accomplishment, and social inclusion. Importantly, these findings shows that people who do not ‘swim’ in the traditional sense, can still have relationship with water, influencing their awareness, attitudes and behaviour regarding water safety.

Migrant adults from various countries, e.g. England, Scotland, Afghanistan, Nepal, often had limited exposure to the water for leisure and recreational purposes prior to arriving in Australia. Participants reported having limited awareness of water safety, shaped by their previous experiences and environments. Findings indicate that after migrating to Australia, there was a positive shift in awareness, knowledge and attitudes towards water safety, an encouraging indication for future drowning prevention efforts. However, challenges exist when accessing further resources and training.

Applying the TPB explicitly to the study findings (Fig. 1), identified that some adult migrants hold normative beliefs when arriving in Australia, such as thinking they would not need to learn to swim themselves, even though their children participated in swimming lessons (, ). Consistent with other studies (, ), parents from migrant backgrounds often recognized early on that swimming was important for their children growing up in Australia but were less focused on their own needs. This reinforces that in many cultures, adults prioritize family needs and put children first (, ).

Control beliefs around learning to swim identified that some adult migrants perceive learning to swim as too difficult or ‘impossible’, however, despite these beliefs many participants showed self-efficacy in making the decision to learn to swim once immersed into Australian life. The TPB may be a useful tool for drowning prevention researchers and practitioners in understanding the underlying social, cultural and normative beliefs influencing an individual's intention to act on a behaviour that provides benefits to themselves and others (e.g. enrolling in swimming lessons). Practically, designing water safety campaigns that address the importance of water safety and swimming knowledge and skills for both children and adults, and promoting culturally sensitive programmes, may influence beliefs, attitudes, and perceived norms of migrant communities towards swimming participation and safety around the water.

Awareness and knowledge

This study identified that migrants from both HIC and LMIC experienced limited exposure to water for leisure and recreational purposes prior to arriving in Australia, consistent with studies of Asian migrants in Australia (), NZ () and the US (, ). However, study participants reported some awareness of water safety and their perceived skills, based on their previous experiences. They also recognized the importance of children's safety around water, and knowing where to swim at Australian beaches.

Adults in this study mainly sourced their water safety information from within their community networks, including family and community members, places of worship, and English language classes. This contrasts with an Australian study of migrants of Indian and Nepalese backgrounds residing in NSW, who sourced beach safety information from online resources or once at the beach (). Methods of communicating health and safety messages for diverse communities have mostly focused on disaster or health risk communication (), particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic (), emphasizing the roles of settlement agencies, education providers and community leaders in delivering risk messages. Despite reliance on media channels, disseminating information through traditional community networks may still be an effective way to reach migrant populations where word of mouth remains a favoured method of receiving information. Learning from how other health promotion sectors have integrated the TPB into the design of health communication campaigns may be useful. For example, campaigns to encourage healthy eating among university students (), or that promote and predict the uptake of vaccinations ().

Attitudes and behaviour

Both male and female migrants reported a shift in awareness and knowledge about water safety and swimming after migrating to Australia, often due to negative experiences in the water or related to their children (e.g. swimming lesson, supervision), consistent with other studies (, ). Negative experiences and a fear of water are common barriers to learning to swim (, ), resulting in reduced exposure to water. This study found that fear and negative experiences directly informed migrants awareness and attitudes towards water safety and impacted their participation regardless of swimming ability (control beliefs) and motivation to learn (behaviour). Fear of water can be generational, with parents’ fear influencing their children's swimming participation (). Adults role modelling safe water behaviour, including learning to swim or wearing a lifejacket, can have an intergenerational impact on their families (). This study suggests that overcoming a fear of water may positively impact entire family and communities’ knowledge, attitudes, and behaviour towards swimming and water safety.

Cultural nuances

An important insight from the findings was the significant role of water in some cultures. Several participants described the rituals and significance that water plays in their culture across the lifespan, ‘from birth to death, different rituals throughout the lifespan is related to water’, contributing to their respect for water. These findings support previous research suggesting that people hold onto their cultural beliefs and rituals related to water when moving to new countries (). This perspective perhaps explains why adult migrants may be reluctant to go in the water for leisure or recreational purposes. Previous studies have also highlighted socio-cultural barriers and perceived benefits in relation to physical activity for improving broader health outcomes (, ).

From a water safety perspective, this means that although people may be frequently exposed to water, they may not be prepared for an unexpected entry into it. It is important that water safety advocates, researchers and practitioners acknowledge and respect traditional cultural beliefs while embedding safety and prevention knowledge. Learning from the Indigenous perspective may be helpful. For example, the spiritual and cultural connection to water among Māori peoples in NZ, and for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in Australia, is deeply entwined with cultural, spiritual, and physical wellbeing. This connection is integral to both individual and community identity (, ). The ‘Wai Puna’ water safety model developed by from the Māori perspective, suggests that local contextual knowledge and environmental ethic may be key in addressing high drowning rates in Indigenous communities globally, acknowledging how Māori communities have ‘an intertwined knowledge and respect for water in all forms’ and interact with the water from both cultural and spiritual perspectives ().

Inclusion and social cohesion

A common theme reported by adults who had learnt to swim, was discovering the joy of swimming, not only from a safety perspective, also for inclusion and equity into the Australian lifestyle. Many participants viewed swimming as a core part of Australian culture, ‘Swimming is part of the DNA’ (in Australia). This study cohort was keen to embrace the Australian ‘culture’ of swimming and aquatic participation regardless of previous experiences and skills. These results are consistent with research involving African migrants in Australia, who were willing to adopt new behaviours and practices of their new host culture to feel a ‘sense of belonging’, whilst maintaining their own cultural and moral values (). However, from a drowning prevention context and for reducing inequalities, these results suggest that some parts of the community may be unintentionally excluded from participating in the Australian culture of aquatic recreation. Some participants were willing to participate in water activities despite limited swimming ability, which may increase their risk of drowning, as it gave them a sense of inclusion.

The study also highlighted that the inability to swim impacted opportunities in other sporting activities, such as triathlons. Participants who learnt to swim in Australia reported feeling empowered to set goals to keep improving, as seen in those who started competing in triathlons. Participation in sport, recreational activities, and volunteering has been shown to reduce inequities and promote positive settlement and assimilation experiences among migrants (, , ). This could be an effective approach to encourage migrant adults to engage with swimming and water safety programmes and other informal/social aquatic-based activities.

Implications

This study highlights that inequalities exist for some adult migrants regarding their safety around water and drowning risk, particularly when migrating to a country with a strong association of aquatic recreation and leisure like Australia. For example, people bring varied experience and knowledge of water, others may have had fewer opportunities to access swimming and water safety education prior to migrating, some people may have a fear of water, stemming from a negative experience, which all shape a person's norms, attitudes, knowledge, and behaviour (positive or negative) around water.

Encouragingly, this study suggests that adults can positively shift their behaviour when exposed to a new environment and experiences. Cultural, normative and control beliefs play a role in shaping awareness, knowledge, attitudes and behaviour among migrant adults, which should be integrated when developing drowning prevention strategies, across policy, research, and practice. Future research should explore culturally informed approaches to water safety, particularly for adults who migrate to countries with a strong culture associated with aquatic recreation and leisure.

Comprehensive drowning prevention strategies that incorporate communities’ social determinants of health are needed to address the inequities faced by migrants in accessing safe places to swim and opportunities to learn essential swimming and water safety skills. At the upstream level, whole of government multisectoral policies and partnerships across education, health and migration sectors are needed (, ), to embed water safety knowledge and swimming education pre- and postmigration. One such example of multisectoral action in drowning prevention is the Thailand Drowning Prevention Strategy, focused on reducing drowning among children, and implemented across government departments (, ).

Access to swimming and water safety information should be made available throughout a person's settlement journey. Research suggests that the time of residence in a new country may play a role in drowning risk, particularly for recent arrivals (, ). For example, migration agencies could offer water safety modules prior to leaving their home country and once in Australia (or other countries), water safety and swimming education could be embedded into Adult English Language Programmes or through migrant settlement support agencies to improve both water safety and English language skills. Some of these types of programmes do exist in Australia, however there is no national consistency, and are often reliant on ad hoc funding (, ). Community-based health promotion programmes could include swimming and other water-based activities, promoting social cohesion and broader health, wellbeing, and fitness for different cohorts of migrants, e.g. parents of young children or elderly people. Several studies from other HIC have highlighted swimming as a low-impact physical activity to address obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular and other noncommunicable diseases, particularly within local community contexts in the UK () and the US ().

Effective policies at the community level need to address equity and access to safe places to swim, and water safety and swimming education for migrant communities. Study participants from a range of different countries, cultures and religions, shared their experiences, barriers and enablers towards swimming, participation and behaviour around the water. Policies and programmes should consider lived experiences and be co-designed with community members to address equity and to ensure cultural sensitivity. Identifying and appointing (paid) community ambassadors or role models to promote the benefits of learning to swim, including social inclusion, employment and competition pathways may also reduce barriers, encourage broader participation among migrant communities and be seen as more acceptable to migrants of all ages.

These findings are applicable at the global level to ensure the health and safety of migrants worldwide. Providing water safety and swimming programmes before migrants are exposed to the water or have a negative experience is imperative and should be a core part of a national comprehensive multisectoral settlement support strategies to ensure that people can purse aquatic activities safely in their new country. While it was beyond the scope of this study, we acknowledge that some migrants may be exposed to drowning risk when they transit by sea between countries, and there is a need to improve migrants’ safety at sea ().

Further research and evaluation related to drowning and water safety among migrants is needed from all countries, not just HIC, to enable learning and development of comprehensive global drowning prevention strategies that address contemporary drowning issues ().

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this qualitative research is that it provides deeper insights than would be gained from data collection methods such as self-reported surveys, or epidemiological studies that cannot explain the decisions that reflect the situation or provide information on the factors leading to a potentially life-threatening situation.

Study participants included migrants residing across Australia, males and females from a range of countries and cultures, of varying length of time in Australia, whose voice may have been neglected in previous drowning prevention research, to gain as many perspectives as possible to inform culturally sensitive drowning prevention initiatives. Including the voices of adult migrants allowed for rich insights that can complement quantitative data and guide practical, real-life drowning prevention policies, programmes and practice.

Applying the TPB to guide the interview questions provided deeper insights into the previous and current awareness, attitudes and knowledge of water safety among a priority population at risk for drowning. The focus on behavioural, normative and control beliefs, was reflected in the emerging themes. Grounding studies and interventions in behavioural change theory helps explain the underlying factors influencing awareness, knowledge and attitudes and has been used extensively across the health promotion field. This approach can inform the development of targeted interventions aimed at addressing these factors, promoting safer behaviours and motivating adult migrants to learn to swim.

A limitation of this study may be the sampling approach used to recruit the participants in this study, which may have introduced a selection bias and limit the representativeness of the findings for all migrants. Interpreters and translators were included in the FGs to increase inclusion; however, their interpretations could also introduce bias. Due to some of the data collection having to change from face-to-face FGs to online interviews, this may have limited the diversity and type of migrants willing to participate in the study and differences in responses between the FG and interview participants may have occurred (e.g. FG participants may have been influenced by group responses). While efforts were made to ensure diversity and inclusivity, the findings may not be generalizable beyond the study population in Australia, or other HICs. We recognize that researcher bias and power may have also influenced the findings, however the research team were conscious of checking their biases throughout the study.

CONCLUSION

This study identified that factors influencing water safety knowledge and awareness among migrant adults in Australia were shaped by their behavioural, normative and control beliefs, including cultural norms and life experiences relating to water. These findings offer new insights to inform contemporary drowning prevention strategies that respond to changing population demographics, in Australia and globally. Understanding the unique health and safety issues which migrants face when moving from one country to another is important as they may be unaware of their water safety needs. A challenge for water safety practitioners is promoting behavioural change in a way which respects cultural and family norms that may be different to their own. This study highlighted that drowning risk determinants among adult migrants, extend beyond factors such as gender, age, and language/communications, which are often the focus of drowning prevention strategies. These broader determinants require more contextualised and inclusive approaches to effectively reduce drowning inequities among adult migrants.

Acknowledgements

We wish to sincerely thank the study participants for their valuable time and insights provided for this study to inform drowning prevention in Australia. Thank you to Justin Scarr for feedback to drafts of the manuscript and the reviewers for their feedback.

This research is supported by the Royal Life Saving Society—Australia to aid in the reduction of drowning. Research at the Royal Life Saving Society—Australia is supported by the Australian Government.

References

- Abercromby M, Leavy JE, Tohotoa J, et al “Go hard or go home”: exploring young people’s knowledge, attitudes and behaviours of alcohol use and water safety in Western Australia using the Health Belief Model. Int J Health Promot Educ 2020;59:174–91. 10.1080/14635240.2020.1759441

- Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process 1991;50:179–211. 10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Akosah-Twumasi P, Alele F, Smith AM, et al Prioritising family needs: a grounded theory of acculturation for Sub-Saharan African migrant families in Australia. Soc Sci 2020;9:17. 10.3390/socsci9020017

- Anderson CN, Noar SM, Rogers BD. The persuasive power of oral health promotion messages: a theory of planned behavior approach to dental checkups among young adults. Health Commun 2012;28:304–13. 10.1080/10410236.2012.684275

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). Australia’s Populations by Country of Birth: Statistics on Australia’s Estimated Resident Population by Country of Birth, 2024. https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/people/population/australias-population-country-birth/latest-release#australia-s-population-by-country-of-birth (28 February 2025, date last accessed).

- Australian Water Safety Council. Australian Water Safety Strategy 2030. Sydney: Australian Water Safety Council, 2021.

- Beale-Tawfeeq AK, Anderson A, Ramos WD. A cause to action: learning to develop a culturally responsive/relevant approach to 21st century water safety messaging through collaborative partnerships. Int J Aquatic Res Educ 2018;11. 10.25035/ijare.11.01.08

- Bierens J, Hoogenboezem J. Fatal drowning statistics from The Netherlands—an example of an aggregated demographic profile. Bmc Public Health 2022;22:e339. 10.1186/s12889-022-12620-3

- Borgonovi F, Seitz H, Vogel I. Swimming Skills Around the World: Evidence on Inequalities in Life Skills across and within Countries, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 281. Paris: OECD Publishing, 2022. 10.1787/0c2c8862-en

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Cenderadewi M, Franklin RC, Fathana PB, et al Child drowning in Indonesia: insights from parental and community perspectives and practices. Health Promot Int 2024;39:daae113. 10.1093/heapro/daae113

- Centre for Sport and Social Impact (CSSI), La Trobe University. Life Saving Victoria Multicultural Program Social Return on Investment, 2021. https://lsv.com.au/social-return-on-investment/ (20 February 2025, date last accessed).

- Creswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, 2018.

- Della Bona M, Crawford G, Nimmo L, et al What does ‘keep watch’ mean to migrant parents? Examining differences in supervision, cardiopulmonary resuscitation training and water familiarisation. Int J Public Health 2019;64:755–62. 10.1007/s00038-018-1197-0

- Delve HL, Limpaecher A. Inductive Thematic Analysis and Deductive Thematic Analysis in Qualitative Research, 2024. https://delvetool.com/blog/inductive-deductive-thematic-analysis (28 January 2025, date last accessed).

- Dou K, Yang J, Wang L-X, et al Theory of planned behavior explains males’ and females’ intention to receive COVID-19 vaccines differently. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022;18:2086393. 10.1080/21645515.2022.2086393

- Fishbein M, Yzer MC. Using theory to design effective health behavior interventions. Commun Theory 2003;13:164–83. 10.1111/j.1468-2885.2003.tb00287.x

- Franklin R, Peden A, Hamilton E, et al The burden of unintentional drowning: global, regional and national estimates of mortality from the Global Burden of Disease 2017 study. Inj Prev 2020;26:i83–95. 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043484

- Gerdmongkolgan S, Ekchaloermkiat S. PA 09-4-1157 A decade of action on child drowning prevention in Thailand. Inj Prev 2018;24:A20. 10.1136/injuryprevention-2018-safety.54

- Gupta M, Roy S, Panda R, et al Interventions for child drowning reduction in the Indian Sundarbans: perspectives from the ground. Children 2020;7:291. 10.3390/children7120291

- Hamilton K, Peden A, Pearson M, et al Stop there’s water on the road! identifying key beliefs guiding people’s willingness to drive through flooded waterways. Saf Sci 2016;89:308–14. 10.1016/j.ssci.2016.07.004

- Hanson-Easey S, Every D, Hansen A, et al Risk communication for new and emerging communities: the contingent role of social capital. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 2018;28:620–8. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2018.01.012

- Irwin CC, Irwin RL, Ryan TD, et al The legacy of fear: is fear impacting fatal and non-fatal drowning of African American children? J Black Stud 2011;42:561–76. 10.1177/0021934710385549

- Irwin J, O'callaghan F, Glendon AI. Predicting parental intentions to enrol their chidlren in swimming lessons using an extended theory of planned behaviour. Aust Psychol 2017;53:263–70. 10.1111/ap.12303

- Irwin CC, Pharr JR, Irwin R. Understanding factors that influence fear of drowning in children and adolescents. Int J Aquatic Res Educ 2015;9:136–48. 10.1123/ijare.2015-0007

- Jagnoor J, Kobusingye O, Scarr J-P. Drowning prevention: priorities to accelerate multisectoral action. The Lancet 2021;398:564–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01601-9

- Jasper R, Stewart B, Knight A. Behaviours and attitudes of recreational fishers toward safety at a ‘blackspot’. Health Promot J Austr 2017;28:156–9. 10.1071/HE16070

- Jepson R, Harris FM, Bowes A, et al Physical activity in South Asians: an in-depth qualitative study to explore motivations and facilitators. PLoS One 2012;7:e45333. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045333

- Jia X, Ahn S, Carcioppolo N. Measuring information overload and message fatigue toward COVID-19 prevention messages in USA and China. Health Promot Int 2022;38:daac003. 10.1093/heapro/daac003

- Koon W, Bennet E, Stempski S, et al Water safety education programs in culturally and linguistically diverse Seattle communities: program design and pilot evaluation. Int J Aquatic Res Educ 2021;13. 10.25035/ijare.13.02.02

- Kothe EJ, Mullan BA, Butow P. Promoting fruit and vegetable consumption. Testing an intervention based on the theory of planned behaviour. Appetite 2012;58:997–1004. 10.1016/j.appet.2012.02.012

- Kyra G, Ava R, Peninah T, et al Mixed-methods community assessment of drowning and water safety knowledge and behaviours on Lake Victoria. Inj Prev 2024;30:496–502. 10.1136/ip-2023-045106

- Moggridge BJ, Thompson RM. Cultural value of water and western water management: an Australian indigenous perspective. Australas J Water Resour 2021;25:4–14. 10.1080/13241583.2021.1897926

- Moran K. Rock-based fisher safety promotion: a decade on. Int J Aquatic Res Educ 2017;10. 10.25035/ijare.10.02.01

- Moran K, Willcox S. Water safety practices and perceptions of “new” New Zealanders. Int J Aquatic Res Educ 2013;7:136–46. 10.25035/ijare.07.02.05

- Moreland B, Ortmann N, Clemens T. Increased unintentional drowning deaths in 2020 by age, race/ethnicity, sex, and location, United States. J Safety Res 2022;82:463–8. 10.1016/j.jsr.2022.06.012

- Myers SL Jr, Cuesta A, Lai Y. Competitive swimming and racial disparities in drowning. Rev Black Polit Econ 2017;44:77–97. 10.1007/s12114-017-9248-y

- Nathan S, Kemp L, Bunde-Birouste A, et al “We wouldn’t of made friends if we didn’t come to Football United”: the impacts of a football program on young people’s peer, prosocial and cross-cultural relationships. BMC Public Health 2013;13:399. 10.1186/1471-2458-13-399

- Oporia F, Kibira SPS, Jagnoor J, et al Determinants of lifejacket use among boaters on Lake Albert, Uganda: a qualitative study. Inj Prev 2022;28:335–9. 10.1136/injuryprev-2021-044483

- Peden AE, Chisholm S, Meddings DR, et al Drowning and disasters: climate change priorities. Lancet Planet Health 2024;8:e345–6. 10.1016/S2542-5196(24)00090-1

- Peden AE, Demant D, Hagger M, et al Personal, social and environmental factors associated with lifejacket wear in adults and children: a systematic literature review. PLoS One 2018;13:e0196421. 10.1371/journal.pone.0196421

- Peden AE, Franklin RC. Learning to swim: an exploration of negative prior aquatic experiences among children. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:3557. 10.3390/ijerph17103557

- Phillips C. Wai Puna: an indigenous model of Māori water safety and health in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Int J Aquatic Res Educ 2020;12. 10.25035/ijare.12.03.07

- Quan L, Bennett E. Attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors around drowning and drowning prevention among Vietnamese teens and parents. J Trauma 2006;60:1383. 10.1097/00005373-200606000-00042

- Quan L, Crispin B, Bennett E, et al Beliefs and practices to prevent drowning among Vietnamese-American adolescents and parents. Inj Prev 2006;12:427–9. 10.1136/ip.2006.011486

- Rice ZS, Liamputtong P. Cultural determinants of health, cross-cultural research and global public health. In: Liamputtong P (ed.), Handbook of Social Sciences and Global Public Health. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2023, 1–14.

- Rogers RW. A protection motivation theory of fear appeals and attitude change. J Psychol 1975;91:93–114. 10.1080/00223980.1975.9915803

- Rosenstock I. Historical origins of the health belief model. Health Educ Behav 1974;2:328–35. 10.1177/1090198174002004

- Saunders NR, Macpherson A, Guan J, et al The shrinking health advantage: unintentional injuries among children and youth from immigrant families. BMC Public Health 2017;18:73. 10.1186/s12889-017-4612-1

- Scarr J-P, Buse K, Norton R, et al Tracing the emergence of drowning prevention on the global health and development agenda: a policy analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2022;10:e1058–66. 10.1016/S2214-109X(22)00074-2

- Scarr J-P, Koon W, Peden AE. Shaping global strategy, mobilising for local action: reflections from the world conference on drowning prevention 2023. Inj Prev 2024a;31:89–93. 10.1136/ip-2024-045368

- Scarr J-P, Meddings DRM, Lukasyk C, et al A framework for identifying opportunities for multisectoral action for drowning prevention in health and sustainable development agendas: a multimethod approach. BMJ Glob Health 2024b;9:e016125. 10.1136/bmjgh-2024-016125

- Shibata M. Exploring international beachgoers’ perceptions of safety signage on Australian beaches. Saf Sci 2023;158:105966. 10.1016/j.ssci.2022.105966

- Sindall R, Mecrow T, Queiroga AC, et al Drowning risk and climate change: a state-of-the-art review. Inj Prev 2022;28:185–91. 10.1136/injuryprev-2021-044486

- Stempski S, Liu L, Grow HM, et al Everyone swims: a community partnership and policy approach to address health disparities in drowning and obesity. Health Educ Behav 2015;42:106S–14S. 10.1177/1090198115570047

- Tate R, Quan L. Cultural aspects of rescue and resuscitation of drowning victims. In: Bierens J (ed.), Drowning: Prevention, Rescue, Treatment. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2014, 399–403.

- Think Tank Olympic Refuge Foundation. Realising the cross- cutting potential of sport in situations of forced displacement. BMJ Glob Health 2022;7:e008717. 10.1136/bmjgh-2022-008717

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007;19:349–57. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Tyr A, Molander E, Bäckström B, et al Unintentional drowning fatalities in Sweden between 2002 and 2021. BMC Public Health 2024;24:3185. 10.1186/s12889-024-20687-3

- United Nations. Resolution adopted by the General Assembly on 28 April 2021. New York: United Nations General Assembly, 2021. https://undocs.org/en/A/RES/75/273 (28 February 2025, date last accessed).

- United Nations International Organization for Migration. The Missing Migrants Project: Deaths During Migration Recorded Since 2014, by Region of Incident, 2024. https://missingmigrants.iom.int/ (5 March 2025, date last accessed).

- Warbrick I, Wilson D, Boulton A. Provider, father, and bro—sedentary M”ori men and their thoughts on physical activity. Int J Equity Health 2016;15:22. 10.1186/s12939-016-0313-0

- Willcox-Pidgeon S, Franklin R, Devine S, et al Reducing inequities among adult female migrants at higher risk for drowning in Australia: the value of swimming and water safety programs. Health Promot J Austr 2020a;32:49–60. 10.1002/hpja.407

- Willcox-Pidgeon S, Franklin R, Leggat P, et al Identifying a gap in drowning prevention: high risk populations. Inj Prev2020b;26:279–88. 10.1136/injuryprev-2019-043432

- Willcox-Pidgeon S, Franklin R, Leggat P, et al Epidemiology of unintentional fatal drowning among migrants in Australia. Aust N Z J Public Health 2021;45:255–62. 10.1111/1753-6405.13102

- Willcox-Pidgeon S, Kool B, Moran K. Perceptions of the risk of drowning at surf beaches among New Zealand youth. Int J Inj Contr Saf Promot 2018;25:365–71. 10.1080/17457300.2018.1431939

- Woods M, Koon W, Brander RW. Identifying risk factors and implications for beach drowning prevention amongst an Australian multicultural community. PLoS One 2022;17:e0262175. 10.1371/journal.pone.0262175

- World Health Organization. Global Report on Drowning: Preventing a Leading Killer. Geneva: WHO, 2014.

- World Health Organization. Preventing Drowning: an Implementation Guide. Geneva: WHO, 2017.

- World Health Organization Commission on Social Determinants of Health. Closing the Gap in a Generation: Health Equity Through Action on the Social Determinants of Health. Geneva: WHO, 2008.

- World Health Organization [WHO]. Global Status Report on Drowning Prevention 2024, 2024a. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. https://www.who.int/teams/social-determinants-of-health/safety-and-mobility/global-report-on-drowning-prevention.

- World Health Organization [WHO]. World Drowning Prevention Day 2024: Thailand's Commitment to Reducing Drowning Incidents, 2024b. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. https://www.who.int/thailand/news/detail/26-07-2024-world-drowning-preventionday-2024-thailand-s-commitment-to-reducing-drowningincidents (30 April 2025, date last accessed).

- Yang C-H, Huang Y-T, Janes C, et al Belief in ghost month can help prevent drowning deaths: a natural experiment on the effects of cultural beliefs on risky behaviours. Soc Sci Med 2008;66:1990–8. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.014