INTRODUCTION

Rating scales (i.e., questionnaires, screening and diagnostic instruments, and instruments to grade the severity of illness) are central to any quantitative research in psychiatry. These are also essential in monitoring the patient’s progress on treatment for any mental health condition and can be equated to investigations in any field of medicine.[] The precisely defined format of the rating scales focuses on the conversation between the respondent and the questionnaire, seeks respondents’ feedback in a comparative form for a particular issue, and improves the collection, synthesis, and reporting of information.[] Rating scales seek to ensure a rapid and complete assessment of a specific construct and provide a score that can help in categorizing and/or quantifying information.[] They enable communication between clinicians and researchers, help in clinical decision-making, and screening and monitoring.[] They are cost-effective measures for carrying out rapid, reliable, and comprehensive measurements.[] Given the above considerations, rating scales are essential to psychiatric research and clinical practice.

Most of the scales used in research and clinical practice have been developed in English. However, not everyone is fluent in English, and there can be substantial variations in its use across countries and cultures. Hence, scales developed in English for a specific cultural background may not directly apply to another culture. A literal translation may not yield valid results, as it could deprive the intended audience of all or some of its meaning. Hence, in addition to translation, there is a need to adapt the scale to suit a different culture. In this context, translation is “the act of converting text or words from one language to another,” while adaptation is “utilizing a known equivalent between two situations.” The translator replaces or adjusts to cultural realities or situations in adaptation. It is a process of establishing cultural equivalence. Adaptation must be considered when an expression may have a more suitable counterpart for a particular circumstance. Accordingly, although adaptation is not necessarily a literal translation, it preserves faithfulness to the original idea. Therefore, the entire translation and adaptation process aims to have a conceptually identical scale or instrument in the index country/culture/language. The instrument’s translation or adaptation should sound as natural and appropriate as the original scale and operate similarly. To put it briefly, the entire process prioritizes conceptual and cross-cultural understanding over linguistic or literal equivalency.[,]

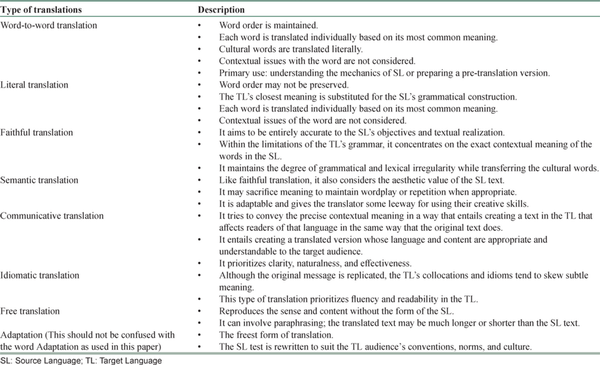

A well-established method of translation involves the use of forward-translations and back-translations.[] In this context, it is essential to understand some related terminology.. The original language in which a scale is developed is known as the source language (SL), and the language to which the scale is to be translated and adapted is known as the target language (TL).[] Further, regarding the approaches to translation adopted, translations are understood as per Newmark’s flattened “V” diagram that suggests that translation involves a spectrum of choices. The “V” diagram represents the range of translation approaches from more SL-oriented to TL-oriented.[] The translation methods that are more oriented toward the SL include word-to-word, literal, faithful, and semantic translations. The methods more oriented toward the TL include adaptation, free translation, idiomatic translation, and communicative translation [Table 1].[] Other authors have also described approaches to translations.[] Among all these translation methods, communicative translation is considered the most appropriate method, especially for translating informative texts, as this type of translation aims to achieve the same effect on the target audience as the source/original text.[]

Table 1

Different types of translations[]

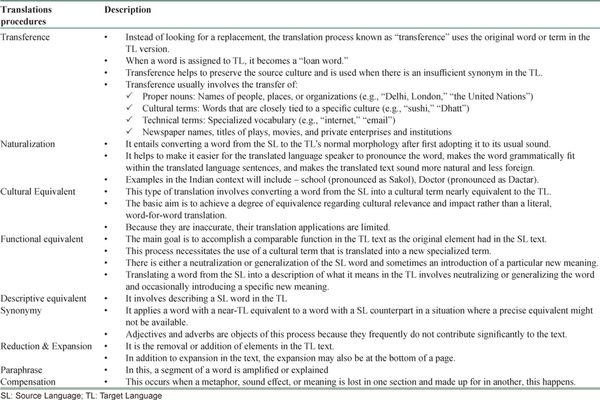

Additionally, the researchers should understand crucial concepts integral to the SL and TL [Table 2].[] A good understanding of these concepts can facilitate the translation and adaptation process, as this can help develop a translated version understandable to the target population.

Table 2

Procedure of translation[]

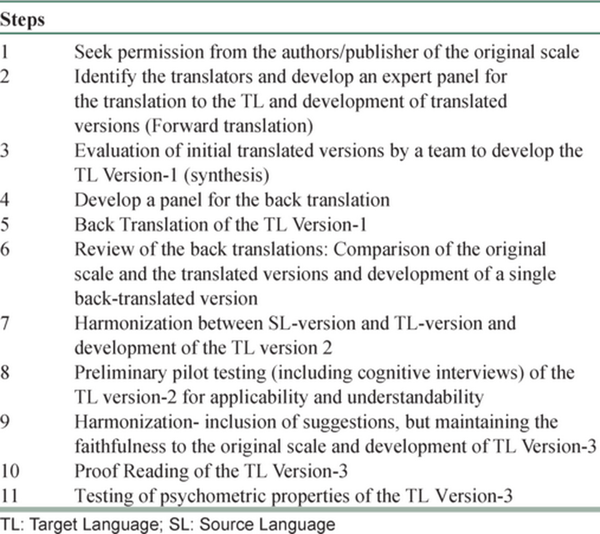

Different authors have described varying numbers of steps, involved in the translation and adaptation,[,] with much overlap between these steps [Table 3]. In the following section, we present the synthesis of information as described by different authors. The first step of translation and adaptation, involves seeking permission from the authors/publisher of the original scale.[] For this, the researchers can write an email to the authors/publishers, as this also helps to keep a record of the same. Once the permission issues are sorted out, in step two, there is a need to identify the translators and an expert panel to review the initial translations.[]

Table 3

Steps involve in translation and adaptation[]

When choosing translators, it is essential to select well-qualified translators to ensure high-quality translations. The initial translation should be done by 2–3 independent translators or teams of translators (teams help to minimize individual bias), depending on the available resources. The translators should be well versed with SL and TL, have TL as their mother tongue, and should come from different backgrounds. One of the translators needs to have experience in the medical field and be familiar with the concept/construct. The second translator should be a lay translator/linguistic expert, conversant in everyday usage of colloquial idioms, health care jargon, idiomatic expressions, and emotional terminology. He should not be familiar with the construct, and should possess extensive knowledge of the SL and TL culture. However, it is often difficult to find ideal translators, and effort should be made to have translators, who fulfill as many requirements as possible. For practical purposes, the expert panel should include one to two mental health professionals and a bilingual language expert. This translation process will lead to two to three translated versions (depending on the resources used) with terms and phrases relevant to medical field and everyday speech with its cultural nuances.

In step three, these translated versions are then compared with the SL version by another person or a team (who are not part of the initial forward translation) who is (/are)bilingual and has (/have) knowledge of both languages (SL and TL). At this stage, the translator(s) evaluates the selected words’ appropriateness and any unclear or inconsistent words, statements, or meanings. Ideally, a team approach is better at this stage, and persons involved in the initial forward translation can be included in the team. A consensus is reached to develop the translated language version-1 (TLV-1) by comparing the translated versions with the SL version (also known as synthesis).

Step four, involves selecting another set of two/three independent translators or teams of translators with the same characteristics as mentioned for the forward translation, except that the mother tongue of the translators should be the SL. These translators ought to be completely unaware of the instrument’s original version (i.e., they should never have viewed or should have gone through the instrument’s original version). In step 5, these translators create two or three back-translated versions. Like the forward translation, step six compares the two back-translations with the original scale in the SL in terms of sentence structure, wording, and format. If there are dissimilarities in meaning and relevance, the expert panel makes the necessary adjustments to produce a single back-translated version.

In step seven, a committee with diverse expertise assesses the back-translated version. This committee should consist of all four translators involved in forward and back-translation (ideally), one knowledgeable healthcare professional aware of the content areas of the scale’s construct, and at least one methodologist. The developer of the SL instrument can also be involved in this stage to clarify the issues that arise in the discussion process and give their input. At this stage, one of the committee members can be a monolingual member with the mother language of TL. With the input of all the participants, TLV-2 is developed. If, at this stage, consensus cannot be reached for some of the items, these can be given to another set of translators, and steps two to seven are repeated for these items.

Throughout the entire process, the goal should be to create a TL version that is conceptually, semantically, and contentwise equivalent to the SL version of the scale. The extent, to which a concept of the instrument’s items overlaps in source and destination cultures is known as a conceptual equivalency. Sentence structure, colloquialisms, or idioms that guarantee the TL retains the meaning of the text or concept of the scale items in the SL is called semantic equivalence. The pertinence and relevance of the text’s or the scale’s items in each culture are reflected in the content equivalency.[]

In step eight, participants whose mother tongue is the TL of the scale are administered the TLV-2 to assess their comprehension of the scale’s items, response structure, and instructions. Participants in this stage should be drawn from the target group for which the scale is intended (for example, if the instrument assesses the quality of life in people with schizophrenia, then persons with schizophrenia must be included in the sample). For this stage, a sample size of 10–40 monolingual people are advised, and each participant should be asked to score the scale’s questions and instructions as “clear” or “unclear.” The participants reporting any of the parts to be unclear should be asked to offer ideas on how to reword the statements to make them more straightforward (cognitive interview). The parts of the instrument that are rated as unclear by at least 20% of the sample must be re-evaluated. This will also ensure a minimum inter-rater agreement of 80% among the sample.[,]

In step nine, the expert panel should evaluate the suggestions given by the participants, and these should be incorporated based on the consensus to develop the TLV-3. In step 10, the TLV-3 is proofread to ensure no spelling and grammatical mistakes. In step 11, the instrument’s psychometric properties are tested in a bilingual population, and the sample size is determined based on the principle of having at least five to ten subjects per item. Ideally, this study sample should be from the target group in which the instrument is intended to be used. However, if this is not feasible, this step can be done among bilingual students and faculty, workers in hospitals, or caregivers of patients.

During this step, to assess cross-language equivalence, participants are initially given TLV-3 and asked to answer the items without viewing the original SL instrument. Then, the participants are given the original SL instrument and are asked to respond to the items. While providing the original version to the participants, the order of the questions should be altered to minimize the practice effect. Further, to reduce the practice effect, there could be a gap of 4–7 days between the two assessments, depending on the type of construct being evaluated by the scale. Then, the responses on both SL and TL versions are compared to assess the cross-language equivalence. If the translated scale is a diagnostic or screening test, a preliminary assessment of sensitivity and specificity is recommended, and this should be compared with the available literature. It is also recommended that various psychometric properties of the translated and adapted instrument be assessed, including criterion and content validation, as well as reliability estimation.[]

During the whole process of translation, wherever there is a deviation from the word-to-word translation or literal translation, it should be noted as an adaptation of the scale, and a note of all the adaptations should be kept, while publishing the information about the translated version of the scale, and the same should be presented. Further, during the translation process, the aim should be to develop a version that conveys the same meaning to the target population as the original scale in the source population where it was designed and translated. Moreover, as suggested in Table 2, different translation procedures should be liberally used, and the emphasis should be on making the scale understandable. It is essential to understand, that while finalizing the translated scale, for every concept, the selection of words should be based on the principle that people with the lowest level of education must be able to understand it. The words used in the translated version should be part of commonly spoken language (rather than chaste words that are often part of literature). Finally, in the Indian context, it is essential to remember that many English words are better understood, even by illiterate people, than the pure words of the TL. Hence, these words should be incorporated in the translation and adaptation process within the framework of maintaining the conceptual, semantic, and content equivalence with the SL version of the scale.

Statement on the generative artificial intelligence technology –

“The authors attest that there was no use of the generative AI technology in the generation of text, figures, or other informational content of this manuscript.”

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

1.

Grover S. How can we use rating scales more appropriately? AP J Psychol Med 2014;15:7–9.2.

Kristjansson EA, Desrochers A, Zumbo B. Translating, and adapting measurement instruments for cross-linguistic and cross-cultural research: A guide for practitioners. Can J Nurs Res 2003;35:127–42.3.

World Health Organization. Process of Translation and Adaptation of Instruments. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2016.4.

Newmark P. A Textbook of Translation. New York: Prentice Hall; 1988.5.

Zepedda AEP. Procedure of translation, transliteration and transcription. Appl Transl 2020;14:8–13.6.

Menon V, Praharaj SK. Translation or development of a rating scale: Plenty of science, a bit of art. Indian J Psychol Med 2019;41:503–6.7.

Sousa VD, Rojjanasrirat W. Translation, adaptation and validation of instruments or scales for use in cross-cultural health care research: A clear and user-friendly guideline. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:268–74.8.

Cruchinho P, López-Franco MD, Capelas ML, Almeida S, Bennett PM, Miranda da Silva M, et al. Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of measurement instruments: A practical guideline for novice researchers. J Multidiscip Healthc 2024;17:2701–28.9.

Kumar K, Kumar S, Mehrotra D, Tiwari SC, Kumar V, Dwivedi RC. Reliability and psychometric validity of Hindi version of depression, anxiety and stress scale-21 (DASS-21) for Hindi speaking head neck cancer and oral potentially malignant disorders patients. J Can Res Ther 2019;15:653–8.