Key Messages:

Following the first clinical posting in psychiatry of the new CBME curriculum,

Students’ knowledge improved, and clinical skills were satisfactory.

Attitudes towards psychiatry were potentially better.

The students’ ratings of self-efficacy in performing the SLOs of the posting and satisfaction with the teaching-learning and assessment methods implemented were high.

Psychiatry is of pivotal importance to undergraduate (UG) medical education in India. However, deficiencies exist in the psychiatry training imparted to UG medical students in the country in the form of inadequate hours of training, inadequately trained teachers, lack of emphasis on issues such as the doctor–patient relationship, emotional problems accompanying physical illnesses and common mental disorders, to name a few.,

The new competency-based medical education (CBME) curriculum presents an opportunity to address these deficiencies. It provides a framework of competencies that the Indian medical graduate must acquire in every subject. Psychiatry includes 117 competencies under 19 topics, although none of the competencies are certifiable. The new curriculum initially included two clinical postings: the first posting in the second professional year of two weeks duration and the second posting in part one of the third professional year of two weeks duration, per the older CBME regulations of 2019. It now includes two clinical postings: the first posting in part one of the third professional year of two weeks duration, and the second posting in part two of the third professional year of four weeks duration, per the updated CBME guidelines of 2023.

Although it has been well received and described as a laudable attempt to modernize medical education, multiple challenges exist: a lack of trained psychiatry teachers required for effective implementation of the new curriculum, a high student-teacher ratio, existing teachers already being overburdened with multiple roles and responsibilities resulting in low acceptance of the new curriculum, negative attitudes among students towards psychiatry, and a lack of innovation and utilization of digital technology in psychiatry training and assessment., Periodic evaluations of the teaching program are necessary to address the challenges encountered and make necessary modifications to the program. Teaching program evaluations in psychiatry from India have examined attitudes towards psychiatry, theoretical knowledge, and clinical skills prior to the introduction of the CBME curriculum., Tharyan et al. reported that the proportion of students with a positive or neutral attitude toward psychiatry increased from 42% before the first clinical posting to 72% after the posting. There was also a statistically significant gain in theoretical knowledge, which was tested by multiple-choice questions (MCQ), in which the mean score improved from 9.9 to 13.9 at the end of the first clinical posting. Behere et al. also reported an improvement in attitude and knowledge about mental health after the first clinical posting in psychiatry of the older curriculum. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published reports of such evaluations of psychiatry teaching programs based on the new CBME curriculum. Our study intends to address this gap in the literature.

Overall, we aimed to assess the effectiveness of the first clinical posting (according to the CBME regulations of 2019) in psychiatry in imparting knowledge and clinical skills and the acceptability of the posting to UG medical students. More specifically, the objectives of our study were to assess UG medical students after the first clinical posting in psychiatry for:

Clinical skills

Change in knowledge

Change in attitudes towards psychiatry

Self-efficacy

Satisfaction with specific teaching–learning and assessment methods implemented.

Materials and Methods

Setting and participants

We performed a cross-sectional study in the Department of Psychiatry at a Medical College in South India from July 2021 to November 2021. The faculty of the Department included thirteen psychiatrists, three clinical psychologists, and three psychiatric social work consultants. The medical college accepts 150 UG medical students per year. We recruited UG medical students in their second professional year posted to the Department for their first clinical posting in psychiatry. Students who had less than 50% attendance to the clinical posting in psychiatry were excluded from the study.

Curriculum and Teaching Program

The curriculum and teaching program was based on the CBME curriculum for the Indian Medical Graduate, and the Draft Competency-Based Medical Education Manual for UG Psychiatry framed by the UG education subcommittee of the Indian Psychiatric Society. As per the CBME curriculum, this was the first of two clinical postings and lasted 10 days, consisting of three hours per day. Twenty-five UG medical students in their second professional year of the MBBS course attended the posting at a time. Each day of the posting would begin with a clinical demonstration session for all the students on a particular topic for which the competencies and specific learning objectives were defined in advance. The session was led by a member of the faculty and lasted typically for 45 minutes. Teaching-learning methods used during these sessions were small group discussions, role-play guided by a script, and clinical demonstrations with the patient. The teachers completed checklists of teaching-learning methods used and specific learning objectives covered during each session. After that, groups of 2–3 students would shadow their ‘clinical guide’ (a designated member of the faculty) for observation of clinical work or would interact with patients assigned to them by their clinical guide. Learning portfolios were used as a teaching-learning method to structure the interactions between the students and their patients, as well as for discussion and feedback from their clinical guides. The formative assessment was an end-of-posting exam consisting of a multiple-choice question (MCQ) test of 10 marks and an objective structured clinical examination (OSCE) test of a simulated patient with depression of 20 marks, based on which feedback was given to each student.

Measures

Demographic data: We assessed participants’ age and sex.

Knowledge: We assessed the students for their knowledge of psychiatry using the MCQ test, which was performed once on the first day of the posting and repeated at the end of the posting. The gain in knowledge of psychiatry was calculated as the difference between the knowledge scores at these two time points. The MCQs were prepared according to standard guidelines, and covered the ‘knows’ and ‘knows how’ specific learning objectives (SLOs) for the topics covered during the posting. There were 10 questions with four response options each, and every question had one correct answer. One mark was awarded for a correct answer, and there were no negative marks for wrong answers or no response.

Clinical skills: At the end of the posting, we used the marks obtained on the OSCE to measure the student’s clinical skills. The OSCE was based on a simulated patient with depression.

Attitudes towards psychiatry: We used the Modified Attitudes to Psychiatry Scale (mAPS), administered on the first day and at the end of the posting, to capture the students’ attitudes towards psychiatry before and after the posting. The mAPS consists of 16 items rated on a 4–point Likert scale from strongly agree to strongly disagree. It contains four subscales: (a) the merits of psychiatry as scientific medicine, (b) effectiveness of treatment, (c) stigma of psychiatry, and (d) inspiration from medical school. The mAPS has been shown to have good internal validity across different geographical regions, including India. Questions 13 to 16 of the mAPS are relevant only after exposure to psychiatry and were therefore excluded from the questionnaire on the first day of the posting.

Self-efficacy: At the end of the posting, we asked the students to rate their degree of confidence in performing particular SLOs by recording a number from 0 to 100 for each SLO, using a scale we constructed for the study with the following anchor points: 0: Cannot do at all, 50: Moderately can do, 100: Highly certain can do.

Satisfaction: At the end of the posting, we asked the students to rate their degree of satisfaction with specific teaching-learning methods, feedback from clinical guides, and assessment methods by recording a number from 1 to 5 for each item, using a scale with the following anchor points: 1) Very dissatisfied, 2) Somewhat dissatisfied, 3) Neither, 4) Somewhat satisfied, 5) Very satisfied.

Scales for confidence and satisfaction were constructed specifically for the study and pilot tested on a group of 13 students. Principal component analysis was performed to ascertain the internal consistency of the confidence and satisfaction scales, and Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.839 and 0.653 were obtained, respectively.

Procedures

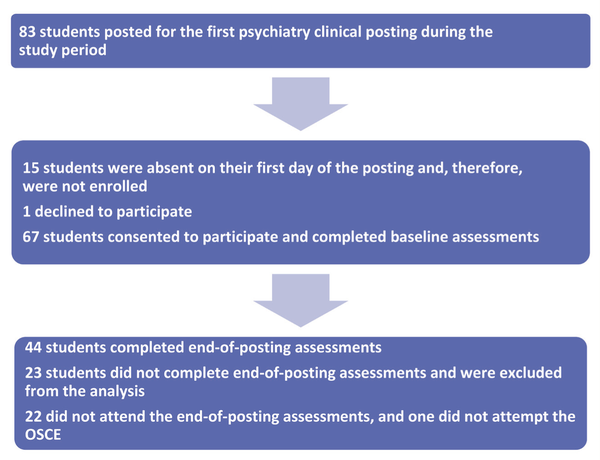

The UG medical students were invited to participate in the study on the first day of the clinical posting. Sixty-seven students consented to participate and completed the assessments on the first day of the posting. Of them, 44 students completed the assessments on the last day of the posting and were included in the final analysis. Figure 1 shows the flow of participants throughout the study.

Participation Details of the Study.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated that a sample of 67 students would be sufficient to observe a mean score of 15.9 out of 20 on the objective structured clinical examination (OSCE), which was the primary outcome measure, with 3% relative precision and a 95% confidence interval. The OSCE scores were available for 44 students, which allowed for the same observation with 3.75% relative precision and a 95% confidence interval.

Descriptive statistics consisted of frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and mean and standard deviation for continuous variables. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to test for normality. The paired t-test was used to compare knowledge scores and attitudes toward psychiatry scores at baseline and after the posting. Analyses were performed using R version 4.2.1.

Ethical considerations

Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee (study no. 147/2021). All participants provided written informed consent.

Results

Out of 83 students posted to psychiatry during the study period, 67 students gave consent to participate in the study. Among them, 44 students completed the end-of-posting assessments, of which 11 (25%) were males, and 33 (75%) were females, with a mean age of 21.6 years. Twenty-three students did not complete the end-of-posting assessments and were not included in the analyses. Among the students who were excluded, 7 (30%) were males and 16 (70%) were females, with a mean age of 20.7 years, a mean baseline knowledge score of 5.26, and a baseline mAPS score of 29.22. The age, sex ratio, baseline knowledge, and mAPS scores were comparable in both the groups-students included and students excluded from the study.

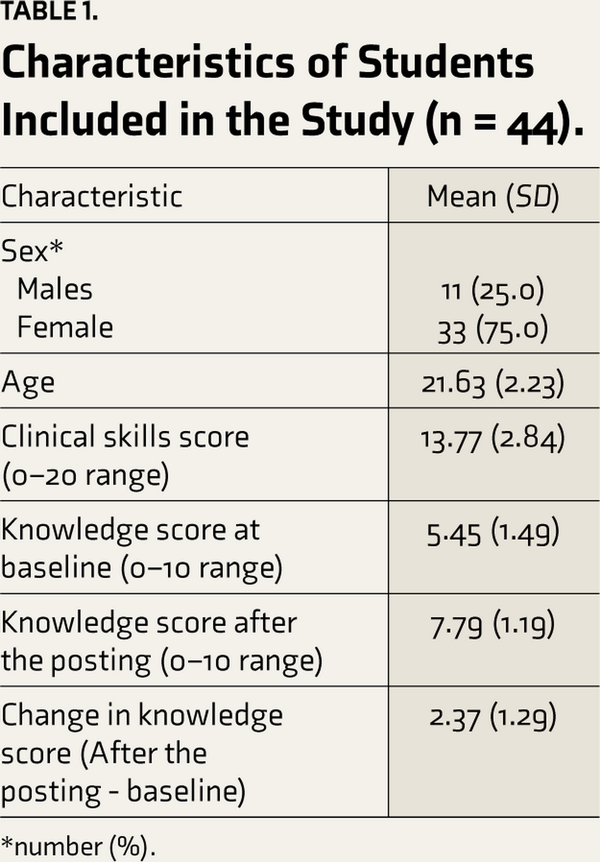

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the study participants and their clinical skills and knowledge scores. The mean knowledge score after the posting was significantly higher compared to the mean knowledge score at baseline (7.79 vs 5.45, p<0.001). The mean clinical skills score after the posting was 13.77.

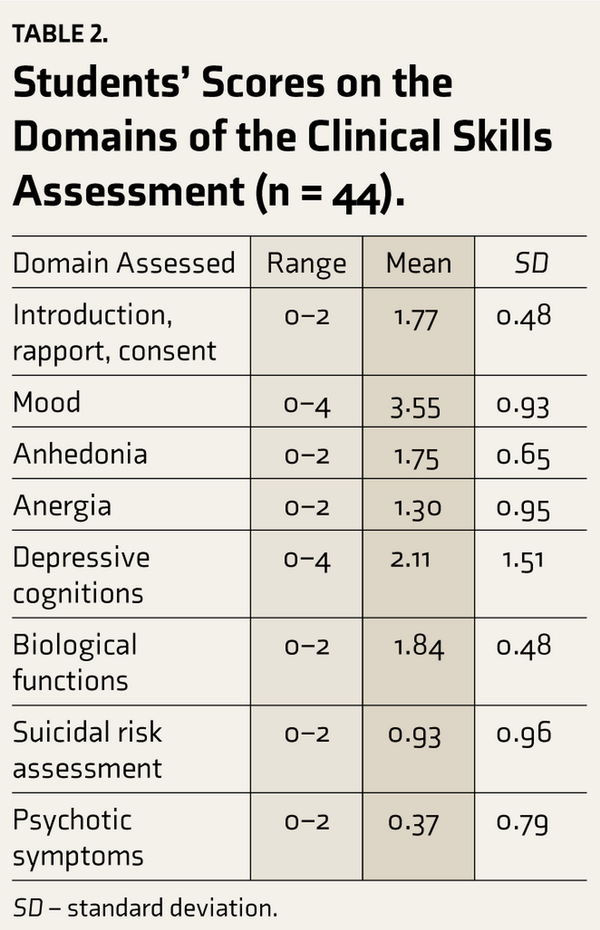

Table 2 shows the scores on various domains assessed as part of the clinical skills assessment. Lower mean scores were seen in the domains of evaluation of depressive cognitions, suicidal risk assessment, and psychotic symptoms.

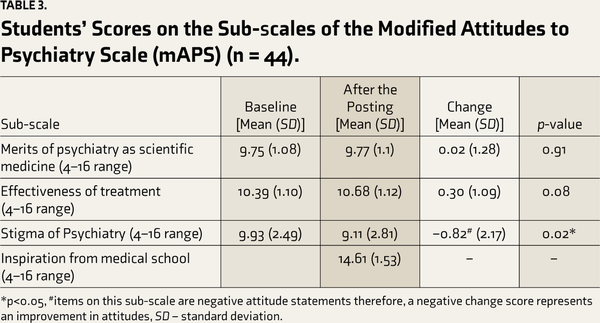

Table 3 summarizes the attitudes toward psychiatry mean scores at baseline and after the posting. Improvement was noted in the mean scores on all three sub-scales of the mAPS scale that were administered at baseline and after the posting. However, the improvement in scores was statistically significant only on the ‘Stigma of Psychiatry’ sub-scale. The mean score on the ‘Inspiration from medical school’ sub-scale was 14.61, measured after the posting.

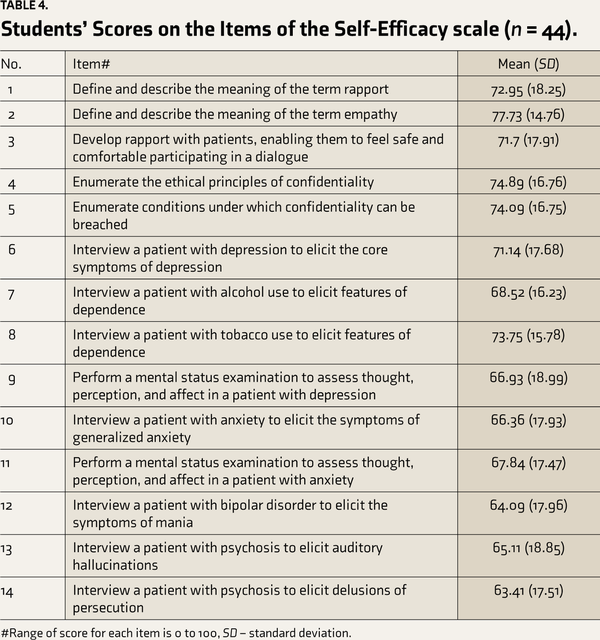

Table 4 shows the mean scores on the self-efficacy scale items. The scores ranged from 63.41 to 77.73 for perceived confidence in performing the SLOs.

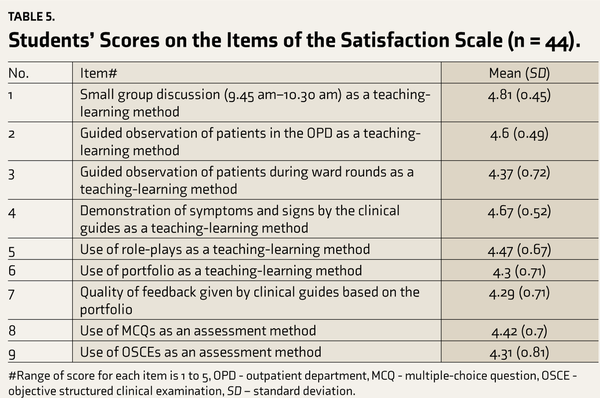

Table 5 shows the mean scores on the satisfaction scale items. The scores on all items were between 4 (somewhat satisfied) and 5 (very satisfied).

Discussion

We describe an evaluation of the first clinical posting in psychiatry of the new CBME curriculum. To our knowledge, this is the first report of a teaching program evaluation following the introduction of the new CBME curriculum. Such program evaluations have been recommended to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of the new curriculum periodically and to make course corrections to ensure its relevance in catering to the needs of society.

The mean knowledge score after the posting was significantly higher compared to the mean knowledge score at baseline, indicating an improvement in the student’s knowledge of psychiatry and, more specifically, for SLOs in the ‘knows’ and ‘knows how’ domains. Thus, the clinical posting was effective in addressing deficits in the knowledge of psychiatry that are known to exist among Indian UG medical students. This finding is aligned with the findings of an earlier study from India that demonstrated significant gains in knowledge among UG medical students in their second year of training, following their first clinical posting in psychiatry based on the older curriculum. Another study from India that described the results of a psychiatry teaching program evaluation also demonstrated significant and sustained improvements in knowledge of psychiatry among medical students.

Following the posting, clinical skills among the students in our study were satisfactory, evidenced by a mean score of 13.77 on the OSCE. Similar results have been described in a previous study from India that examined the efficacy of a psychiatry training program in imparting clinical skills to UG medical students. Relatively lower mean scores were seen in the domains of evaluation of depressive cognitions, suicidal risk assessment, and psychotic symptoms, indicating that these were specific areas in which clinical skills were deficient, and, therefore, greater emphasis needs to be provided during training.

Attitudes towards psychiatry among the students in our study improved in the domains of ‘the merits of psychiatry as scientific medicine,’ ‘effectiveness of treatment,’ and ‘stigma of psychiatry’ but was statistically significant in only the last domain. The mean score on the ‘inspiration from medical school’ domain measured after the posting was 14.61 (4–16 range), with the students endorsing statements such as ‘Teaching of psychiatry at my medical school is interesting and of good quality’ and ‘Most psychiatrists at my medical school are clear, logical thinkers.’ This reflects a positive attitude towards the teachers and the training received during the posting. This is an encouraging finding, given that negative attitudes towards psychiatric patients and psychiatrists have been shown to be prevalent among Indian UG medical students, which can persist even after exposure to a clinical posting in psychiatry., , Another study from India found no benefit of additional online training in improving UG students perceptions of psychiatry. A few studies from India have demonstrated an improvement in attitudes towards psychiatry among UG medical students following a clinical posting in psychiatry, similar to our findings.,,

The students’ scores on the self-efficacy scale ranged from 63.41 to 77.73 (0–100 range) for perceived confidence in performing various SLOs of the clinical posting, indicating sufficient confidence in the performance of the SLOs. This finding also provided additional validation of our findings of improvement in knowledge and satisfactory performance of clinical skills. Similarly, a study from South Africa that assessed UG medical students’ perceptions regarding their career readiness after their clinical rotation in psychiatry found that students perceived themselves to be career-ready if they had sufficient exposure to mentally ill patients, knowledge about prescribing appropriate psychiatric medication, and especially psychiatric interviewing skills.

The mean scores on all items of the satisfaction scale for the teaching-learning methods, assessment methods, and feedback received were between 4 (somewhat satisfied) and 5 (very satisfied). This implies high levels of student satisfaction with the teaching-learning methods deployed during the clinical posting, including novel teaching-learning methods like learning portfolios. It also implies that student satisfaction with assessment methods like MCQs and OSCE and feedback provided to the students based on their performance on the same was high. This is reassuring since the utilization of ‘low touch’ teaching methods like learning portfolios and assessment methods like MCQs and OSCE can help surmount structural barriers, like disproportionate student–teacher ratio, in the proper implementation of the new CBME curriculum.

Future research could focus on evaluating other components of the new CBME curriculum for UG psychiatry, such as the second clinical posting, theory lectures, small group learning, and self-directed learning. Program evaluations of the entire psychiatry teaching program will also be necessary to ensure periodic course corrections to ensure its relevance in meeting the needs of society.

Strengths

Our study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to evaluate the first clinical posting in psychiatry of the new CBME curriculum on several parameters. It included students from across the country, which increases the generalizability of our findings.

Limitations

Our findings may not be generalizable to medical colleges with structural constraints like fewer teachers or a lack of space to accommodate students, especially in the OPD. The generalizability of our findings is also limited by the fact that it is a single institution-based study. The assessment of clinical skills was done only after the posting; therefore, we were unable to capture the change in clinical skills from before the posting. Social desirability bias may have influenced the scores on the attitudes towards psychiatry, self-efficacy, and satisfaction scales.

Conclusion

We have described the evaluation of the first clinical posting in psychiatry of the new CBME curriculum. The posting was effective in imparting knowledge and clinical skills and potentially bringing about favorable changes in the attitudes toward psychiatry among UG medical students. The students also perceived confidence in performing the SLOs and were satisfied with the teaching-learning methods and assessment methods implemented.

The authors gratefully acknowledge Ms. Aswathi Saji and Mr. Bartholomew Carvalho for their assistance with the statistical analyses.

Author contributions Conceptualization- Luke Joshua Salazar, Priya Sreedaran, Uttara Chari

Author contributions Data collection- Luke Joshua Salazar, Shalini Perugu, Bhuvaneshwari Sethuraman

Author contributions Data analysis- Luke Joshua Salazar, Shalini Perugu

Author contributions Writing- Luke Joshua Salazar, Priya Sreedaran, Uttara Chari, Shalini Perugu, Bhuvaneshwari Sethuraman

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Declaration Regarding the Use of Generative AI None used.

Ethical Approval Ethics approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee, St. John's Medical College (study no. 147/2021).

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Informed Consent All participants provided written informed consent.

References

- 1. Kallivayalil RA. The importance of psychiatry in undergraduate medical education in India. Indian journal of psychiatry, 2012; 54(3): 208.

- 2. Kishor M, Isaac M, Ashok MV, Pandit LV, Rao TS. Undergraduate psychiatry training in India; past, present, and future looking for solutions within constraints!!. Indian journal of psychiatry, 2016; 58(2): 119.

- 3. National Medical Commission. Competency-based undergraduate curriculum [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nmc.org.in/information-desk/for-colleges/ug-curriculum/. Accessed , .

- 4. National Medical Commission. Regulations on graduate medical education (amendment), 2019 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nmc.org.in/ActivitiWebClient/open/getDocumentpath=/Documents/Public/Portal/Gazette/GME-06.11.2019.pdf. Accessed , .

- 5. National Medical Commission. Competency-based medical education guidelines, 2023 [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nmc.org.in/MCIRest/open/getDocument?path=/Documents/Public/Portal/LatestNews/CBME%201.pdf. Accessed , .

- 6. Jacob KS. Medical Council of India’s New competency-based curriculum for medical graduates: A critical appraisal. Indian journal of psychological medicine, 2019; 41(3): 203.

- 7. Gupta S, Menon V. Psychiatry training for medical students: A global perspective and implications for India’s competency-based medical education curriculum. Indian J Psychiatry, 2022; 64(3): 240–251.

- 8. Sahadevan S, Kurian N, Mani AM, Kishor MR, Menon V. Implementing competency-based medical education curriculum in undergraduate psychiatric training in India: Opportunities and challenges. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 2021; 13(4): e12491.

- 9. Tharyan A, Datta S, Kuruvilla K. Undergraduate training in psychiatry an evaluation. Indian journal of psychiatry, 1992; 34(4): 370.

- 10. Behere PB, Chowdhury D, Behere AP, Yadav R. Medical students attitude & knowledge of psychiatry an impact of psychiatry posting. Journal of Pharmaceutical Research International, 2021; 21: 270–276.

- 11. Indian Psychiatric Society. Draft competency-based medical education manual for UG Psychiatry, https://indianpsychiatricsociety.org/draft-competency-based-medical-education-manual-for-ug-psychiatry/ (accessed ).

- 12. Van Tartwijk J, Driessen EW. Portfolios for assessment and learning: AMEE Guide no. 45. Medical teacher, 2009; 31(9): 790–801.

- 13. National Board of Medical Examiners. NBME item-writing guide [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nbme.org/item-writing-guide. Accessed , .

- 14. Shankar R, Laugharne R, Pritchard C, Joshi P, Dhar R. Modified attitudes to psychiatry scale created using principal-components analysis. Academic Psychiatry, 2011; 35(6): 360–364.

- 15. Bandura A. Guide to constructing self-efficacy scales. In: Urdan T, Pajares F (eds) Self-efficacy beliefs of adolescents (Vol. 5). Greenwich, CT: Information Age Publishing, 2006, pp. 307–337.

- 16. Moosa MY, Jeenah FY. The assessment of undergraduate psychiatry training: A paradigm shift. African Journal of Psychiatry, 2007; 10(2): 88–91.

- 17. Aruna G, Mittal S, Yadiyal MB, Acharya C, Acharya S, Uppulari C. Perception, knowledge, and attitude toward mental disorders and psychiatry among medical undergraduates in Karnataka: A cross-sectional study. Indian journal of psychiatry. 2016; 58(1):70–76.

- 18. Desai ND, Chavda PD. Attitudes of undergraduate medical students toward mental illnesses and psychiatry. Journal of education and health promotion, 2018; 7(1): 50.

- 19. Sharma A, Vankar GK, Behere PB, Mishra KK. Does clinical posting in psychiatry change attitude towards psychiatry? A prospective study. Journal of Clinical and Scientific Research, 2018; 7(3): 106–113.

- 20. Prathaptharyan TJ, Annatharyan DE. Attitudes of tomorrow’s doctors towards psychiatry and mental illness. Natl Med J India, 2001; 14: 355–359.

- 21. Chandran N, Menon V. Effect of online customized psychiatry teaching on the perceptions about psychiatry among undergraduate medical students: A randomized controlled study. Kerala Journal of Psychiatry, 2022; 35(2): 112–121.

- 22. Konwar R, Pardal PK, Prakash J. Does psychiatry rotation in undergraduate curriculum bring about a change in the attitude of medical student toward concept and practice of psychiatry: A comparative analysis. Industrial Psychiatry Journal, 2012; 21(2): 144–147.

- 23. Gulati P, Das S, Chavan BS. Impact of psychiatry training on attitude of medical students toward mental illness and psychiatry. Indian journal of psychiatry, 2014; 56(3): 271–277.

- 24. Desai R, Panchal B, Vala A, Ratnani IJ, Vadher S, Khania P. Impact of clinical posting in psychiatry on the attitudes towards psychiatry and mental illness in undergraduate medical students. General Psychiatry, 2019; 32(3): e100072.

- 25. Ives K, Bekker PJ, Lippi G, Kruger C. Do medical students feel career-ready after their psychiatry clinical rotation? South African Journal of Psychiatry, 2019; 25(1): 1–8.

- 26. Fisher RJ. Social desirability bias and the validity of indirect questioning. J Consum Res, 1993; 20: 303–315.