Stigma” is a Greek term originally referring to bodily signs such as a burn or a cut to denote a negative/depreciative condition referred to a person (e.g., being a slave, a criminal, a sinner, or a social outcast) and, therefore, to indicate which people should be “avoided.” Currently, stigma is not usually related to a purely physical sign but frequently includes the negative discriminatory thoughts, feelings, and behaviors towards people with certain physical, behavioral, or racial features perceived as displeasing or a threat by other members of the society.

Since its appearance in December 2019, COVID-19 has fueled fear, anxiety, and panic worldwide, due to its novelty, high infectivity, and absence of effective evidence-based treatment., Faced with this blurry and uncertain situation, fear and its associated behaviors are not uncommon human reactions. The wide media coverage of the pandemic has contributed to the spread of the fear of contagion and subsequent stigmatizing behaviors. Following the declaration of COVID-19 as a pandemic, people around the world easily adopted stigmatizing beliefs and behaviors towards those diagnosed with COVID-19 and their close contacts and also places, people (e.g., healthcare workers [HCW]), and ethnic groups (e.g., Chinese people) believed to be the cause of the pandemic.,

Stigma and Infectious Disease Outbreaks

The manifestation of stigma during infectious disease outbreaks takes several forms, including isolation and verbal and physical aggression. These occur at various levels, including individual (self-stigmatization), interpersonal, and institutional. Currently, across the globe, people receiving treatment for COVID-19 and their families are experiencing different forms of stigmatizing and discriminatory behaviors. Following the trend of other infectious disease outbreaks, we do not expect these to end anytime soon unless drastic measures are taken to decrease the coming stigma epidemic.–

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, those affected with many other infectious diseases, such as Hansen’s disease (commonly known as leprosy), tuberculosis (TB), human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome (HIV/AIDS), and the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) had faced the damaging impact of stigma.– Despite the differences in the above infectious diseases in terms of at-risk populations and mode of transmission, their association with stigmatizing beliefs and behaviors highlights the importance of addressing stigma associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, individuals who suffer from any condition associated with stigma may develop self-discrimination that significantly influences their behavior, such as a decrease in the use of health services, with consequent poorer health outcomes. Self-stigma is a component of the wider social phenomenon of stigma when negative stereotypes and prejudices about a certain condition are widespread in the common thinking of the population. This is widely known for noncommunicable diseases, such as severe mental illness (SMI), substance use disorders (SUD), and epilepsy and communicable diseases such as HIV, and as such, could also occur in people with COVID-19. Research on how stigma had hindered the control of the above-mentioned infectious disease outbreaks might also shed some light on the potential impact of stigma in the battle against the COVID-19 pandemic. The literature reports that stigma associated with a diagnosis can drive individuals to undertake behaviors that increase the risk of transmission to others, such as delaying testing,, concealing symptoms,, and avoiding healthcare., During the Ebola virus disease (EVD) outbreak, stigmatization of patients and relatives through social isolation and verbal and physical abuse led to an alienation of people from the government. This brought about a decrease in case reporting and contact tracing and, ultimately, an exponential increase in the number of EVD cases. While implementing preventive and protective measures during the rapid spread of an infectious disease, particular care should be taken to not turn them into stigmatizing measures.

It is also important to acknowledge and address the significant impact of stigma on the mental health of the affected population and HCWs.– During a pandemic, stigma may worsen the fear and anxiety in the general population and may result in the development of certain mental health conditions. Social stigma towards certain diseases has been associated with a negative impact on public health efforts., , Stigmatizing attitudes may result in emotional disturbances such as worries, anxiety, and a sense of helplessness. The mental health impact of an infectious disease may occur not only during the pandemic but also in the postpandemic period. Fear and stigma can lead to social isolation, which may reduce the social support that HCWs and people who are infected need, preventing them from receiving the much-needed mental health support.

COVID-19 represents a new challenge due to the speed of the outbreak, the singularities of its not fully understood infective patterns, and its emergence in a globalized world with limitless real-time exchanges of communication. In particular, lockdowns and other measures of physical distancing have limited the possibilities of face-to-face interactions. Nevertheless, strategies to understand and address the stigma related to it can find inspiration in what has proven effective in other general medical diseases (i.e., HIV and TB)– and SMI. Common strategies to reduce stigma, which have heterogeneous levels of evidence, frequently use a multilevel approach and have been largely based on education, social contact (through the use of telecommunication means), counseling, problem-solving, advocacy, and social marketing., ,

COVID-19-Related Stigma

Description of COVID-19-related stigma in the represented countries was provided by the co-authors, using a semistructured guide that addressed negative and depreciative terminology referring to the coronavirus and people with COVID-19, common rumors and myths present globally about COVID-19, stigma-related behaviors and attitudes towards certain ethnic groups and communities during all phases of the pandemic, and the presence of antistigma initiatives or interventions towards COVID-19-related stigma.

Negative terminologies identified in the represented countries, contributing to COVID-19-related stigma included terms such as “Chinese virus,” “rich man’s disease,” “corona case,” “Wuhan virus,” and “Chinese plague.” These negative terminologies were rampant in all sampled countries and were found to form the basis of the stigmatizing beliefs and behaviors. Regarding myths and rumors contributing to stigma, the belief that the pandemic was a religious curse or a biological weapon by the Chinese was identified across the countries. In some countries, there were rumors about governmental involvement in the spread of the virus. This led to distrust in the government by the people and, consequently, discouraged them from abiding by the strategies aimed at controlling the pandemic. In religious countries, the pandemic was attributed to a religious curse and those diagnosed were stigmatized for being “spiritually unclean.” During the early phase of the pandemic, when the majority of those diagnosed with COVID-19 were travelers, there was much stigma towards people traveling into the represented countries as well as migrants of Asian descent. There was anger towards various governments for allowing people to travel into the countries. This led to people hiding their travel history for fear of stigmatization. In some countries, there were public demands for a list of people diagnosed with COVID-19 to be made public. These stigmatizing attitudes and beliefs led to various governments adopting some form of antistigma strategies, such as CDC guideline against stigma in the United States.

Amid unpredicted and ambiguous outbreaks, it is not uncommon for people to create and spread myths (i.e., beliefs that contradict logic or evidence) and misinformation through rumors (i.e., unsubstantiated ideas that may or may not be true, presented as definitive truths grounded on sound evidence), possibly to relieve their uncertainty and fears about the situation. Myths vary from one culture to another and are usually driven by the sociohistorical, traditional, and religious background of the community. During the COVID-19 pandemic, religious-themed misconceptions and myths have been widely spread in various countries, with some religious leaders and traditional healers having laid claim to possessing cures. Such beliefs might increase the stigma towards the illness, as those who become infected could be then labeled as “nonbelievers” or “sinners.” Other forms of myths and misconceptions about COVID-19, not religious, can also lead to stigmatizing behavior towards those with the illness., Unsubstantiated beliefs, such as that the infection is a bioweapon developed by a government or terrorist organization, that people of African origin do not get the infection, or that the virus is transmitted via mail packages and products from China, might increase the stigma related to the illness, particularly when the infection becomes tagged to a particular ethnic or racial group.

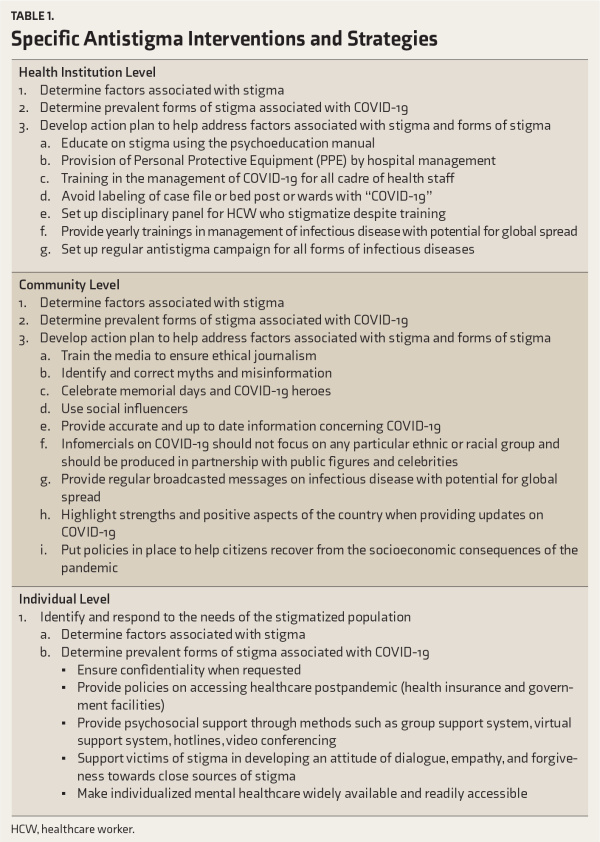

Country reports from our semistructured guide highlight the need to adopt and perform pertinent measures and interventions to fight the already experienced COVID-19-associated stigma worldwide. We developed a psychoeducational guide tailored to the general population, intended to address COVID-19-related stigma. Emphasis was laid on correcting negative terminologies, using neutral terminologies, and correcting myths and misinformation. This psychoeducational guide can be used by the general public and in the training of media personnel to ensure ethical reporting of COVID-19-related news, to decrease stigma (Box 1). Furthermore, a mental health preparedness action framework, described below, was developed to integrate antistigma strategies and interventions at every stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, using the previously published conceptual framework for mental health intervention as a guide. A set of general interventions, strategies, and conceptual guidelines too was developed to address key points related to stigma and to suggest measures and tools that can be used in the fight against COVID-19-related stigma (See Table 1).

Recommendations to Combat COVID-19-Related Stigma

Stigmatizing beliefs and behaviors affect not only the control of the outbreak, thus contributing to a greater number of people being infected, higher mortality, and greater socioeconomic consequences on the affected communities, but also may have had short- and long-term negative consequences on the mental health of those affected, HCWs, and the affected communities.– Antistigma activities and strategies should be developed ahead of time and carefully planned for, tailored, and progressively adapted throughout the COVID-19 pandemic to suit the specific phase of COVID-19 outbreak in each country. This framework emphasizes the need for continuous surveillance of interventions and appropriate communication to all stakeholders to decrease the mental health consequences attributable to COVID-19-related stigma.

Box 1.COVID-19-Related Antistigma Psychoeducation Guide

Education to the general public should focus on the negative misconceptions, terminologies, myths, and rumors that have been shown to be instrumental in propagating discriminatory and stigmatizing beliefs and behaviors. Concerning the COVID-19 pandemic, below is a suggested guide for psychoeducation.

Raise awareness about COVID-19 without disseminating fear, social panic, paranoia, or anger

Avoid social rejection and violent behavior towards stigmatized categories (i.e., healthcare workers, Asian people, etc.)

Avoid geographical/ethnic/racial-connoted names for the SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19.

Avoid negative terminologies (i.e., “Chinese virus,” “rich man’s disease,” “wealthy people’s disease,” “Wuhan virus,” “viral apocalypse,” “COVID-19 plague,” “Wuhan pneumonia”)

Avoid negative or depreciative terminologies referring to people with COVID-19 (i.e., “COVID-19 case,” “COVID-19 suspect,” “suspected case,” “positive,” “positive case,” “infected,” “corona case”)

Avoid negatively connoting terminologies to refer to healthcare workers (e.g., “potentially infecting healthcare worker”)

Encourage neutral terminology (i.e., “people with,” “people who have,” “people who are being treated,” “people who have recovered,” “people who died after contracting”)

Respect confidentiality, anonymity, and privacy

Discourage stigmatizing behaviors towards

Chinese and Asian people (i.e., migrants, citizens/residents)

people who relocated from higher risk areas

people who have recently traveled

healthcare professionals and emergency responders

Discourage dissemination of rumors and myths (“false facts”). Correct misconceptions by using accurate and scientifically based information to clarify myths based on local cultures, such as

Conspiracy theories about the origin of the virus as a bioterrorist attack/war/biological warfare

China vs America, America vs China

Conspiracy theories about the origin of the virus as laboratory designed by pharmaceutical companies to sell the vaccine

Conspiracy theories about the reasons/motivations for dissemination of the virus, such as:

It is specifically designed to kill older adults due to overpopulation, the raising of the average age, poor financial resources to provide them, etc.

It is a divine tool (part of a superior divine plan)

It is aimed to rebalance the natural equilibrium (recently dysregulated due to air pollution, human beings, technology, overheating, etc.)

Conspiracy theories about the modality to disseminate the virus

5G technology

eating in Chinese, Asiatic, Asian fusion, or Japanese restaurants

receiving letter/packages from China

buying and wearing Chinese dresses

by other vaccines (“no-vax theory”)

The false and firm belief that

the virus is not so severe, but the government wants to disseminate this false information

spring and summer will eradicate the virus (due to the high temperatures)

the virus cannot spread in tropical countries

some ethnic groups (e.g., Indonesian people, African descents) are protected from the virus “Miracle”/bizarre remedies to kill the virus

using essential oils, saltwater, sodium bicarbonate, some herbs, plants, vacuum steam; chewing garlic; drinking hot water; drinking alcoholic beverages; smoking cigarettes; gargling with bleach, acetic acid, etc.

Religious and mystic practices, including remaining confined in holy places

Public Authorities

At the national and local levels, create a public office responsible for:

receiving stigmatic information and threats

prevention and promotion of positive beliefs and attitudes

coordination of research about the sources and means of propagation of stigma

mediation with mass and social media and influencer groups

Provision of a dedicated helpline to address the concerns of both victims of stigma and people who might be fearful and unsure about how to behave when being next to infected or exposed individuals.

At the local level, provision of social mediators (i.e., a person trained in social work with good communication skills) who can help in promoting dialogue and solve discrepancies among neighbors when there is a concern about how the proximity of a high-risk individual or neighbor diagnosed with COVID-19 impacts the others.

Health Authorities

Involve in public education and sharing of resources and in training HCWs to help assess and heal those affected by stigma.

Develop a support network for HCWs who are at increased risk of COVID-19-related stigma.

Create means at the institutional level to report COVID-19-related stigma.

Law Authorities

Create effective and dedicated channels to allow victims and witnesses to report stigmatizing behaviors and get a rapid response.

Provide information about the legal consequences of stigmatizing behaviors.

Social and Mass Media

Social media platforms should monitor and rapidly flag or remove (when appropriate) contents that contravene their terms of use and promote violence or discrimination against individuals or groups.

Editors and producers of mass media platforms are responsible for ensuring the truthfulness of their contents and the promotion of positive attitudes.

Information should be provided timely, with proper context and realism, avoiding pointing out at certain groups or individuals and overwhelming with an excess of news and negative contents, while highlighting hopeful messages and appreciation for HCWs and other people providing essential services.

The public would benefit from attaching “human faces” to those suffering from COVID-19 and its consequences, by hearing positive stories of recovery and solidarity.

Influencer Groups and Individuals

Be aware of the power of their messages and behaviors among the public.

Self-testimonies and supportive attitudes from celebrities and community leaders are perceived as helpful, and their interventions during the current pandemic may spread hope and inspiration.

Structured social groups, such as religious organizations, should watch the potential confusion of facts about COVID-19 and cultural and religious beliefs while powerfully harnessing their influence and structure to provide information and support to their members.

General Public

Be aware that stigma is often originated and propagated inadvertently by individuals without ill intentions.

The general public and individuals are the first line of preventive, identification, and intervention strategies as they are the primary supporters of the affected individuals.

Good educational and informative efforts would lead them to feel responsible for keeping up to date about the facts regarding the virus and the effective physical distancing measures, to spread truthful information, and to identify their feelings and fears about the pandemic and the affected or exposed individuals in their proximity.

A sense of empathy and constructive dialogue with those infected or exposed to coronavirus should be encouraged to prevent stigmatizing attitudes and behaviors as much as possible.

Every individual should feel responsible for speaking up and intervening proportionately against the stigmatizing attitudes they witness and for asking for forgiveness and palliating the effects of their potential attitudes if it is the case.

Empathetic dialogues with victims and potential sources should be encouraged.

All should be aware that the measures of physical distancing between each other, and especially with regards to those infected or exposed, do not preclude individuals from showing civility and kindness and providing support to all, particularly to those most affected.

Social contact strategies to reduce stigma could be implemented by fostering close telecommunication between the public and the affected individuals.

The above strategies to combat COVID-19-related stigma can be tailored at the institutional, community, and individual levels, as seen in Figure 1, and tailored to fit any phase of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Conclusions

Preventing the dissemination of stigma-related attitudes and behaviors may help decrease the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, as stigma may lead to underreporting of symptoms and decrease the use of health facilities. Public authorities, by their greater visibility, should be exemplary in their language and behavior and should promote a sense of collective endeavor. Education is the key to address this challenge. COVID-19-related stigma can be mitigated by educating the general population and media, by adapting our language and terminology, by celebrating those at the forefront of the pandemic, by fighting myths and misinformation, and by putting down policies to protect most people, including HCWs, who were infected and have survived COVID-19. Furthermore, mental health professionals should also plan to implement antistigma interventions in the postpandemic period to limit self-stigma amongst survivors and HCWs.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Early Career Psychiatrists Section of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA) for being a supportive network that allowed to connect early career psychiatrists from different countries to work together on this initiative.

- 1.

- 2. Ransing R, Adiukwu F, Pereira-Sanchez V Mental health interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a conceptual framework by early career psychiatrists. Asian J Psychiatr 2020; 51: 102085.

- 3. Pereira-Sanchez V, Adiukwu F, El Hayek S COVID-19 effect on mental health: patients and workforce. Lancet Psychiatry 2020; 7: e29–e30.

- 4. Ho Su Hui C, Ho CS, Chee CY Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singap 2020; 49: 155–160.

- 5. Misra S, Le PD, Goldmann E Psychological impact of anti-Asian stigma due to the COVID-19 pandemic: A call for research, practice, and policy responses. Psychol Trauma 2020; 12: 461–464.

- 6. Adja KYC, Golinelli D, Lenzi J Pandemics and social stigma: Who’s next? Italy’s experience with COVID-19. Public Health 2020; 185: 39.

- 7. Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Weiss E Reducing HIV-related stigma: Lessons learned from horizons research and programs. Public Health Rep 2010; 125: 272–281.

- 8. Cianelli R, Ferrer L, Norr KF Stigma related to HIV among community health workers in Chile. Stigma Res Action 2011; 1: 3.

- 9. Van Bortel T, Basnayake A, Wurie F Effets psychosociaux d’une flambée de maladie à virus ebola aux échelles individuelle, communautaire et international. Bull World Health Organ 2016; 94: 210–214.

- 10. Kongoley-Mih PS. The impact of Ebola on the tourism and hospitality industry in Sierra Leone. Int J Sci Res Publ 2014; 5: 542.

- 11. James PB, Wardle J, Steel A An assessment of Ebola-related stigma and its association with informal healthcare utilisation among Ebola survivors in Sierra Leone: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health 2020; 20: 182.

- 12. Courtwright A, Turner AN. Tuberculosis and stigmatization: Pathways and interventions. Public Health Rep 2010; 125: 34–42.

- 13. Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: A review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS 2008; 22 (Suppl 2): S67.

- 14. Person B, Sy F, Holton K Fear and stigma: The epidemic within the SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis 2004; 10: 358–363.

- 15. Rafferty J. Curing the stigma of leprosy. Lepr Rev 2005; 76: 119–126.

- 16. Corrigan PW, Rao D. On the self-stigma of mental illness: Stages, disclosure, and strategies for change. Can J Psychiatry 2012; 57: 464–469.

- 17.

- 18. Matthews S, Dwyer R, Snoek A. Stigma and self-stigma in addiction. J Bioeth Inq 2017; 14: 275–286.

- 19. Kirabira J, Forry J Ben, Kinengyere AA A systematic review protocol of stigma among children and adolescents with epilepsy. Syst Rev 2019; 8: 21.

- 20. Pantelic M, Steinert JI, Park J ‘Management of a spoiled identity’: Systematic review of interventions to address self-stigma among people living with and affected by HIV. BMJ Glob Heal 2019; 4: e001285.

- 21. Chesney MA, Smith AW. Critical delays in HIV testing and care. Am Behav Sci 1999; 42: 1162–1174.

- 22. Sambisa W, Curtis S, Mishra V. AIDS stigma as an obstacle to uptake of HIV testing: Evidence from a Zimbabwean national population-based survey. AIDS Care 2010; 22: 170–186.

- 23. Cremers AL, De Laat MM, Kapata N Assessing the consequences of stigma for tuberculosis patients in urban Zambia. PLoS One 2015; 10: e0119861.

- 24. Simbayi LC, Kalichman SC, Strebel A Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners and sexual risk behaviours among HIV-positive men and women, Cape Town, South Africa. Sex Transm Infect 2007; 83: 29–34.

- 25. Steward WT, Bharat S, Ramakrishna J Stigma is associated with delays in seeking care among HIV-infected people in India. J Int Assoc Provid AIDS Care 2013; 12: 103–109.

- 26. Obilade TT. Ebola virus disease stigmatization: The role of societal attributes. Int Arch Med 2015; 8: 1755–7682.

- 27. Kang E, Rapkin BD, DeAlmeida C. Are psychological consequences of stigma enduring or transitory? A longitudinal study of HIV stigma and distress among Asians and Pacific Islanders living with HIV illness. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2006; 20: 712–723.

- 28. Maunder RG, Lancee WJ, Balderson KE Long-term psychological and occupational effects of providing hospital healthcare during SARS outbreak. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12: 1924–1932.

- 29. Verma S, Mythily S, Chan YH Post-SARS psychological morbidity and stigma among general practitioners and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singap 2004; 33: 743–748.

- 30.

- 31. Mak WWS, Mo PKH, Cheung RYM Comparative stigma of HIV/AIDS, SARS, and tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med 2006; 63: 1912–1922.

- 32. Andersson GZ, Reinius M, Eriksson LE Stigma reduction interventions in people living with HIV to improve health-related quality of life. Lancet HIV 2020; 7: e129–e140.

- 33. Sommerland N, Wouters E, Mitchell EMH Evidence-based interventions to reduce tuberculosis stigma: A systematic review. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 2017; 21: S81–S86.

- 34. Morgan AJ, Reavley NJ, Ross A Interventions to reduce stigma towards people with severe mental illness: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2018; 103: 120–133.

- 35. Logie CH, Turan JM. How do we balance tensions between COVID-19 public health responses and stigma mitigation? Learning from HIV research. AIDS Behav 2020; 24: 2003–2006.

- 36. Mehta N, Clement S, Marcus E Evidence for effective interventions to reduce mental Healthrelated stigma and discrimination in the medium and long term: Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry2015; 207: 377–384.

- 37. Rao D, Elshafei A, Nguyen M A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: State of the science and future directions. BMC Med 2019; 17: 41.

- 38.

- 39. Menon V, Padhy SK, Pattnaik JI. Stigma and aggression against health care workers in India amidst COVID-19 times: Possible drivers and mitigation strategies. Indian J Psychol Med 2020; 42: 400–401.

- 40.

- 41.

- 42. Taylor S, Landry CA, Rachor GS Fear and avoidance of healthcare workers: An important, under-recognized form of stigmatization during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Anxiety Disord 2020; 75: 102289.

- 43. Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20: 782.

- 44.

- 45. Bhattacharya P, Banerjee D, Rao TS. The “ untold” side of COVID-19: Social stigma and its consequences in India. Indian J Psychol Med 2020; 42: 382–386.