Key Message:

The study highlights how community involvement can create opportunities or barriers to participate in mainstream society, which can have an impact on an individual’s sense of self, coping with illness, social support, treatment-seeking behavior, and relationship with mental health professionals.

Schizophrenia affects around 21 million people worldwide, most living in developing countries. The severe and chronic nature of schizophrenia often leads to pervasive impairment in a person’s psycho-socio-occupational functionality. These impairments naturally impact subjective well-being, family atmosphere, social network, and meaningful integration into local and extended communities. Also, structural barriers such as poverty, unemployment, and homelessness make persons with schizophrenia (PwS) vulnerable to situational stress. There would also be sociocultural barriers such as negative stereotypes and prejudices in a society that label PwS and isolate them. The isolation can further deteriorate their health status and quality of life. All these would be associated with negative illness experiences.

The illness experience of persons with mental illness is widely researched. Borg and Davidson assessed the subjective experience of persons with mental illness, including schizophrenia, its consequences on their day-to-day lives, and how they derive a sense of meaning from those experiences. The study participants associated “being normal” with being able to spend time with normal people in the community, being positive, and keeping busy by engaging in pleasurable recreational activities, all of which helped them develop a sense of belonging in the community.

The PwS perspective on “experiencing community” is influenced by a sense of belongingness and connectedness to the community, which also depends on the extent of help and support they receive, further allowing them to identify with others. Their community activities and the use of community resources influence their subjective experience of living in the community.,

Most of these studies are conducted in developed countries. In developing countries like India, there are differences in the course and outcome of mental illnesses, which could be because of various factors such as social and gender-based inequalities and a flawed community-based service delivery model that has not been able to provide low cost, effective mental health services in rural and remote areas. The exploration of sociocultural factors plays a vital role as illnesses like schizophrenia impact different domains of a person’s life. These cultural differences necessitate studying the experiences of PwS in the Indian context. Therefore, the current study explored how PwS identify with their illness, what sense they make of their experience, and how do they describe their unique experiences regarding their capacity, talents, and opportunities, which affect their recovery. The study also focuses on assessing how community involvement creates opportunities or barriers for PwS to participate in mainstream society.

Methods

The present study used an interpretative phenomenological approach (IPA). The participants were PwS availing outpatient services at a tertiary health care center in Bengaluru, South India. PwS were included if they were 18 years or above, had a minimum illness duration of one year, had been hospitalized more than twice (to consider the illness to be severe and chronic), had been staying in the community for the past six months or more, and had been maintaining well based on the Clinical Global Impression Scale scoring (≤4), which indicated the severity of the illness.

The data collection was carried out between August and September 2019.

Tools for Data Collection

The participants’ background information was collected using the research team’s semistructured sociodemographic and clinical profile tool. An in-depth interview guide was developed, based on the literature review and experts’ opinions, to explore the lived experience of PwS. The interview guide was face and content validated by six experienced mental health professionals (MHPs) and pilot tested on two PwS. Further modifications were made by simplifying the questions and adding a few more prompts. This final version of the interview guide was used for data collection. The interview guide consists of open-ended questions related to the four domains discussed in Table S1.

Interview Process

All participants were assured confidentiality and interviewed in complete privacy in the counseling rooms of the hospital. The interview was conducted in a single session ranging from 45 min to 60 min. Six participants were recruited. After the fourth interview, no new codes or themes emerged. But the researcher continued data collection for two more interviews to ensure and confirm that no new themes or codes are emerging. Therefore, at the sixth interview, it was considered that the data collection had reached a saturation point. This sample size fits with Smith and Shinebourne recommendation for three to six participants for research using IPA, as the emphasis put is mainly on getting a detailed account of an individual’s experience of the phenomenon being studied.

Data Processing

The interviews were audio-recorded as first-person narratives (in Hindi language). The audio recordings were transcribed and translated by the lead researcher (AR), who was fluent in both Hindi and English. The lead researcher also checked the accuracy of the transcriptions by matching them with the audio recordings. Three levels of exploratory notes were maintained, which helped the researchers become more inductive in approach. The first level was maintaining descriptive notes, which focused on noting how the participants described their experiences through words, phrases, or other descriptive statements. The second was the linguistic level, which focused on commenting on the ways participants used language to describe their experiences by using laughter, pauses, or repetition. The third was the conceptual level, where the researcher focused on a broader understanding of the participants’ experiences, which helped the researcher move away from participants’ explicit descriptions of the phenomenon. The lead researcher also maintained a reflective journal that she started keeping at the beginning of the study. She documented in it the research process, including design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation. The exploratory notes and the reflective journal were written in English and analyzed along with the transcriptions.

Data Analysis

The lead researcher maintained the ideographic nature of data analysis by analyzing the first interview transcript in great detail before moving on to the other transcripts. Analysis was carried out by following the principles of Hermeneutic Circle, which takes an iterative approach to data analysis by returning to the interview transcripts as a whole to ensure that the participants’ words, phrases, and individual statements or ideas are considered within the context of the transcripts in its entirety. All the transcripts were read multiple times, a codebook was developed where the coding of the domains was done, three levels of exploratory noting were maintained, and then themes were constructed. To ensure the quality of coding, a double-blind procedure was adopted where two members from the research team (AR and SP) independently generated the codes and themes and then verified the consistency of the codes with the transcripts. The disagreements between the two about the codes were resolved with discussion to reach a consensus. Later, the final codes were imported into a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet for mapping and connecting the themes.

Ethical Considerations

The Human Ethics Committee of the institute had approved the study. The participants were briefed about the study, and written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. To protect the identity of participants, a code number was assigned to the interview transcripts, and the study results were reported without any identifying information.

Results

Eight participants were screened for eligibility, of which six (male = 2, female = 4) met the inclusion criteria. The sociodemographic and clinical details of the participants are described in Table 1.

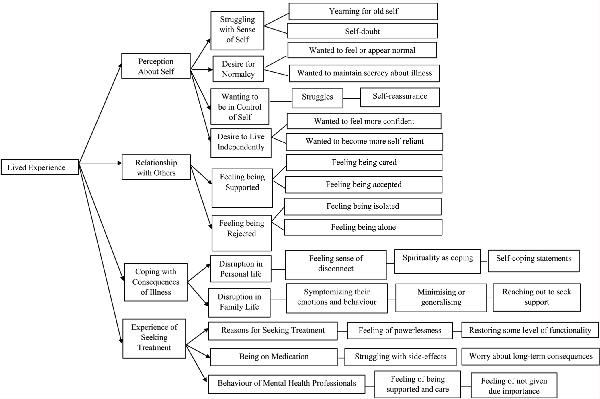

Each of the six participants genuinely expressed a desire to share their story as they wanted others to understand what it is like to live with schizophrenia. At the same time, talking about their life allowed them to look at their own journey in terms of how far they have come in terms of their illness and recovery process. Throughout the interview, the participants shared their feelings about living with chronic mental illness like schizophrenia, but they also felt proud about their achievements, small or great, despite the challenges they have experienced. As the participants navigated through their experience, they weaved their stories around four major themes: (a) perception about self, (b) relationship with others, (c) coping with consequences of the illness, and (d) experience of seeking treatment. Within each theme, many subthemes emerged, which are presented as a coding tree in Figure 1.

Mapping of Main Themes and Subthemes

Perception About Self

The experience of mental illness affected how the participants understood and perceived “self.” They felt that as the illness became chronic, it was taking hold of their lives, making them feel embarrassed, insecure, and defeated. The experience of seeking treatment and being on medication led to further redefining of the “self.” This process of trying to understand and redefine “self” continued as they learned to live with the illness. Four subthemes emerged which showed how living with chronic schizophrenia impacted participants’ perception about self included: (a) struggling with sense of self, (b) desire for normalcy, (c) wanting to be in control of self, and (d) desire to live independently.

Struggling with Sense of Self

Even though years have passed since they first learned that they had schizophrenia, three of the participants shared that they continue to struggle with questions about their identity, which often resulted in self-doubt, yearning for old self, and struggling to make sense of a self- outside of their mental illness. One of the participants shared how she keeps questioning, who she was before the onset of the illness, who she has become now, and who she has to be so that the society can readily accept her. She opined, “Now and then, I keep thinking what my life was before. I used to wear my confidence on my sleeves. My friends used to say,

Oh, look at her… How confidently she talks…. I was the pride of the family. But now it’s hard. Sometimes I get these feelings: Am I the same person? Am I capable of making any decisions in life now? But I have to get back my confidence…, learn to do things that will help me fit in the society. (P5, 28-year-old female)

A Desire for Normalcy

Being diagnosed with schizophrenia made the participants feel different from others. Four participants expressed their desire to feel or appear normal by reassuring themselves that they can live their everyday lives with the help of the medication. Two of them reported that they prefer not to tell others about their illness, to avoid being judged or stereotyped, which led to their isolation and marginalization. One participant stated, “I want them to know me for the good things I have… I prefer to be seen as friendly, good-hearted, and intelligent. I want to prove to others that having schizophrenia does not mean being a nuisance to others” (P4, 35-year-old male).

Two of the participants shared how they remained careful of their behavior when in public, appearing as normal as possible, and tried not to draw undue and unwanted attention to themselves. One participant report,

When I go to the mall with my friends, I try smiling and appearing friendly. I wear clothes that are lively and colorful… If I have to attend a party, I spend a lot of time thinking what I should wear and how I should talk… Sometimes I even practice it in front of the mirror, which helps me feel better and calmer. (P3, 27-year-old female).

Wanting to Feel in Control of Self

As participants’ illness progressed with time, it influenced their thinking, perceptions, emotions, and behavior and left them feeling not in control of their sense of self. Five participants reported that they were struggling to have control over their lives and described how they confronted themselves with the thought of not being in control of themselves. They often provided reassurance to themselves that their illness was not that severe and controllable, and they also focused on their internal strength to become self-reliant. One participant stated, “It’s all within us…. The moment we accept our illness, it becomes easy for us…focus on what you have, not on what is already gone…” (P1, 25-year-old female).

Desire to Live Independently

Living with chronic schizophrenia impacted participants’ ability to live independently. Participants desired a sense of independence in their day-to-day life, to feel more confident, to develop a sense of trust in their abilities, and to become more self-reliant. One participant reported, “I really don’t like my husband calling and checking on me all the time…I want him to understand that I can do things on my own without him instructing me to do things. I want to live how everybody lives at my age” (P5, 28-year-old-female).

Relationship with Others

Chronic schizophrenia impacted how participants experience themselves in relation with others. The participants shared their experiences regarding their relationship with family and friends as they continued to live with their illness. Two subthemes emerged that described the participants’ struggles and success in maintaining a relationship with others: (a) feeling supported by others and (b) feeling rejected by others.

Feeling Supported by Others

Participants felt cared for by the family members whenever there was an exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms. This sense of being cared for was expressed by the participants when they shared their feeling of appreciation and gratitude for the support system they had, even though they were still in the process of struggling to understand the fluctuations in their psychiatric symptoms. One participant noted, “I could see how much my elder sister suffered seeing me like this…My sister reads a lot, so she would often Google and try to find out what could be done to make me feel better” (P2, 30-year-old male).

Another participant explained how her mother would support her whenever she heard voices,

I talk to my mom whenever I cannot bear those sounds, and she gives me counseling. She tells me that it is ok… it is just a sound…It is not going to do anything to me. I have to stop paying attention to it. She would also ask me to distract my mind by listening to music. (P3, 27-year-old female)

Feeling Rejected by Others

Two of the participants shared their experience of struggling to make sense of what was happening to them as their illness progressed. One participant stated,

I wanted my mom and dad to understand it is not easy for me either…I do not do it intentionally. The moment I hear those voices talking about how I am having sex with every man on the street… It is very difficult not to react…There are days when I can ignore those voices, but at times I scream and yell at them (voices). I can see how embarrassed my parents feel because of my behavior. (P1, 25-year-old female)

Coping with Consequences of the Illness

As the participants’ illnesses progressed and became chronic, there were many fluctuations in their symptoms, making it quite challenging to manage their day-to-day lives. Two subthemes that reflected their struggles and challenges were (a) coping with disruptions in personal life and (b) coping with disruptions in family life.

Coping with Disruptions in Personal Life

Participants shared their experience of being less confident, worrying about the future, being not able to remember things, fear of being judged in a social situation, and as a result socially isolating themselves. One participant said, “I am an introvert but never had a problem if somebody started talking to me. Now I feel blank… or forget what they were saying…I also feel what if I say something wrong…” (P4, 35-year-old male).

Another participant described her pain of not being able to connect to her children, “I can see my daughters are closer to my mother than me. They tell her everything. I am not able to listen and respond to my daughters the way my mother does” (P5, 28-year-old female).

Participants used several coping mechanisms to deal with frustrations and mood fluctuations resulting from disruptions in their personal lives. One participant explained how being spiritual made her feel more optimistic, “My ways of looking at things are different because I believe in God. I do not know how to say…The Almighty sees everything. He knows I am struggling, and He is there for me…” (P6, 33-year-old female).

Another participant tried to reassure himself by using self-coping statements as it made him feel better and stronger. Others tried to cope by keeping themselves busy, structuring their day by some other activity or having some routine, and trying to be consistent with that.

Coping with Disruptions in Family Life

Two female participants shared their experience of being physically and sexually abused by their spouses. Their experience was so traumatic that they could not find appropriate words to describe it. One participant reported,

My husband does not come home often. Sometimes he will come at night, and if I am sleeping, he wakes me up and insists on having umm…you understand, I assume. If I deny, he beats me and says that I am mad, which is why I cannot satisfy him…. It is so painful, especially on days when I am having my periods. (P5, 28-year-old female)

Whenever participants expressed their feelings and views, family members symptomized their behavior, making participants feel quite frustrated and powerless. One participant stated, “If you cry, you are considered depressed. If you are laughing and happily talking to others without becoming angry or irritated, then you are manic” (P2, 30-year-old male).

Two participants described their feelings of being voiceless as their families often dismissed their opinion and viewpoint. One participant stated, “At home, I do not talk much…Whatever I say is not given much importance because no matter how reasonable I might sound, the label of being schizophrenic makes me unreliable as if there is no other part of me that is sensible or good” (P4, 35-year-old male).

These negative experiences made participants feel helpless, worthless, and even angry. They were physically and emotionally exhausted trying to cope with it. One participant minimized and generalized the experience of sexual abuse: “I just saw it normal thing in marriage. Many times, when you are not interested, your husband will force you to sleep with him” (P5, 28-year-old female).

Other participants tried to seek support by ventilating to friends and family members. When the participants felt they would no longer stand the situation, they sought help by approaching MHPs.

Experience of Seeking Treatment

Participants had positive and negative experiences of seeking treatment, and changes they observed within themselves over time, and hopes and fears related to treatment. Three subthemes emerged that reflected their experience: (a) reasons for seeking treatment, (b) being on medication, and (c) behavior of MHPs.

Reasons for Seeking Treatment

The participants had various reasons to seek treatment, the most prominent being fear and confusion about fluctuations in their symptoms, restoring some level of functionality that will help them lead a productive life, and feeling powerless because of not having control over their symptoms. One participant described her experience of seeking treatment:

I was having a really bad time of my life as my relationship with my husband, children, and parents was getting so much affected because of my mood fluctuations. I was hearing multiple voices that asked me to die. I got so much lost in those thoughts that I stopped eating or sleeping…Even if my children were standing in front of me, I could not see them. That was the time I realized I really needed some help. (P6, 33-year-old female)

Being on Medication

Participants acknowledged how medicines have helped them control their symptoms, but they also struggled and had difficulties with medication. Some difficulties they experienced were side effects of medicines, worry about long-term consequences of taking medicines, and concerns about the future. One participant described her experience of taking medicine,

I feel sleepy all the time and have gained so much of weight. I can see how restless I have become as I cannot sit in one place for a long time. I also do not go out much because when I speak, people are not able to understand as my speech has become very slow. (P1, 25-year-old female)

Another participant expressed his worry about medicines having harmful effects on his internal organs. In contrast, another participant wanted to stop medicines once his symptoms were controlled, but he was concerned about getting his symptoms back, which may create difficulty in achieving his personal goal of clearing civil service examination.

All the participants had accepted taking medicines as a part of their life, but they felt defeated as whenever they stopped medicines, they relapsed, which made them realize that they had to take medicine for a long time, maybe forever.

The Behavior of MHPs

Participants had mixed feelings about their relationship with MHPs. One participant shared her experience of being supported by a MHP during the ups and downs in her treatment. She stated,

I had always trusted my doctor and sought her advice and guidance when I had to take important decisions in life…Whether it is about my marriage, work, or moving out of my parents’ home…Many times, I would not turn up for follow-up or come when I had a relapse, but my doctor would never give up on me and was always supportive. (P3, 27-year-old female)

Another participant shared her feelings of the MHP not giving her much time or importance, which made her feel disappointed, hurt, and mistrusted. She reported,

Whenever I come for consultation, I prefer to come alone; otherwise, the doctor will talk to my family and prescribe medicine without even looking at me or asking me what I have to say…I am often not comfortable talking about things in front of my family as I have to go back and live in the same house. Also, I do not know if the doctor will believe me or what my family is saying…. (P1, 25-year-old female)

Discussion

We examined the lived experiences of individuals with chronic schizophrenia living in a community in India. The participants had a lot of concerns or reactions about specific aspects of living with chronic schizophrenia, such as the experience of onset of illness, being diagnosed with schizophrenia, being on medication, receiving treatment, and living their day-to-day lives with the illness. Overall, there were four critical themes, which are discussed further:

Perception About Self

When the participants’ symptoms began to develop and evolve, it significantly affected their conceptualization of self. The symptoms affected their thoughts, feelings, emotions, and behavior, leaving them confused, lost, and difficult to define who they were and what they were becoming now. It resulted in existential concerns about true self versus false self, linked to Laing’s theory of self, where true self represents participants’ feelings and desires, while the false self represents their side that has changed because of illness. Participants tried to safeguard their true selves by living their day-to-day life as usual as possible to protect themselves from rejection. They hid aspects of self that the illness had changed. In order to feel and appear normal, they tried to rediscover their true self, which they considered hidden beneath their psychotic symptoms. They often tried to prove themselves that they had control over their illness and that their true self was not being affected by their illness.

The participants also wanted to live a meaningful life focusing on those aspects of their lives, skills, and talents that were not affected by their illness. One study had reported that the process of integrating one’s identity in a chronic illness is a complex and challenging task that requires consistent efforts. In addition to that, Paterson states that living with chronic illness is a complex coexistence between living a life and living an illness. A person continuously shifts between the two, trying to regain self or wellness and live a meaningful life. Kelly and Gamble considered how a family views a person’s capacity to recover, brings hope for recovery in persons with severe and chronic mental illness, builds self-confidence, and makes them self-reliant.

Relationship with Others

Our participants felt cared for by the family members whenever there was an exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms because of noncompliance to medicines or psychosocial stressors. Min and Wong reported that family plays a vital role in the recovery of persons from mental illness. During the recovery process, a person requires support in socialization and accessibility to material and tangible resources to address challenges in their day-to-day life and effective management of their illness.

All participants struggled with their desire to connect with others versus their need to isolate themselves from others. The participants’ longing to isolate themselves primarily came from having experienced rejection or abandonment by significant others (e.g., relatives, friends, or acquaintances) at different times in their lives. With fluctuations in their symptoms, many times, even without experiencing outright rejection by others, participants developed feelings of shame and embarrassment, leading to social withdrawal and the desire to isolate themselves.

Coping with Consequences of the Illness

Because of the fluctuations in their psychiatric symptoms and fears related to the unpredictability of relapse, the participants were worried about their future, which impacted their self-esteem and led to the fear of being judged by others in social situations. The social-cognitive model of internalized stigma suggests that internalized stigma may negatively affect recovery-related outcomes such as self-esteem, hope related to the future, self-efficacy, perceived quality of life, and sense of relatedness with others, which subsequently impacts psychological functioning and social support of the individual.,

Many participants also reported difficulty remembering things, and that was, at times, quite frustrating for them. Multiple studies have shown how working memory deficits are quite common in schizophrenia spectrum disorder, supported by the hypothesis that the prefrontal cortex is impaired in PwS., The literature that focused on motherhood among women with chronic mental illness has reported that such women have difficulty relating with the child and feel less competent as a parent, which was also reported by one of our participants., Our participants used several coping mechanisms to deal with the frustrations caused by fluctuations in their symptoms, which can be explained through the cognitive-behavioral model, which emphasizes how a person’s illness and treatment cognitions affect their emotional response to illness and usage of coping strategies. There is a significant relationship between hope and coping: if a severely mentally ill person positively reappraises a stressful situation, it helps them cope well with negative emotional experiences, adapt, and look forward to have a better future. Those who have hope mostly use a positive coping mechanism like engaging in spiritual practices, often use self-coping statements, and keep themselves busy in routine everyday activities.

The literature also suggests gender differences in the choice of coping used by men and women with mental illness. Women mainly cope with discrimination and abusive experiences by normalizing the abuse and developing a sense of helplessness and fear. At the same time, social connectedness is valued more strongly by females than males., Lynch examined the relationship between optimism, coping, and quality of life in individuals with chronic mental illness and found that the higher the level of optimism, the more active is the coping style and the greater the quality of life. Compared to men, women with severe mental illness experience a higher risk of victimization as estimated by one of the systematic reviews: the prevalence of sexual and physical abuse among women was 15% to 22% and among men was 4% to 10%. The present study also confirms that women with chronic mental illness are vulnerable to physical and sexual abuse, which was reported by one of the female participants. Multiple studies have reported that often women with mental illness might experience intersection oppression and abuse because of stigma related to mental illness, sexist attitude, poverty, patriarchy, and substance abuse in their partner.–

Some of our participants reported invalidation, as the family attributed their expression of feelings and emotions to be part of their illness, and their opinion and viewpoint were not considered necessary, which is consistent with findings of various studies., These studies stated that persons with severe mental illness commonly experiencing microaggression in the form of invalidation are considered inferior compared to others and are treated as second-class citizens because of fluctuations in symptoms and chronicity of illness. Family loses hope for recovery, which results in these discriminatory and rejecting experiences.

Experience of Seeking Treatment

Our participants have been seeking treatment to cope with their symptoms and gain a sense of control over their lives. Research on treatment engagement in severe mental illness has reported numerous factors that maintain a person in treatment. They could be patient-related (e.g., education, income level, and beliefs about treatment efficacy), illness-related (e.g., duration of illness, symptom severity, and comorbid conditions), or treatment-related (e.g., type of treatment, effectiveness of treatment, patient-doctor relationship, and treatment adverse effects).,

Limitations and Strength

The present study focused on the participants’ recollection of experiences with their illness throughout their lifetime, which might have been impacted by difficulties related to their illness, medications, or present emotions coloring their past experiences. The study has a relatively small sample size, making it difficult to generalize the findings. We took only those PwS who were in contact with the outpatient psychiatric department of a single tertiary hospital. So, our findings cannot be generalized to PwS who were highly symptomatic, have dropped out from treatment, never received treatment, or received treatment from a private clinic or hospital. Research indicates that such individuals’ treatment outcomes and experiences may differ., Another limitation could be the predominance of female participants. Evidence suggests that the gendered experiences of schizophrenia may differ because of differential social role expectations, which are shaped by sociocultural norms, social support, changes in family dynamics, and stigma experienced after the onset of the illness.,

Nevertheless, the present study’s uniqueness was that all the participants had an illness duration of more than 10 years, making their experience rich to share.

Future Directions

Future researchers should focus on conducting a longitudinal study that follows individuals with chronic schizophrenia over a longer period to determine whether the events that occur in their life are static or dynamic in shaping their experiences, the critical moments and processes involved, and the causes of the changes and their consequences on their experiences. Observing their experiences over time through time-varying predictors and outcomes will help provide casual inferences about their experiences. Another exciting area could be examining the lived experiences of males and females with chronic schizophrenia from rural and urban settings and comparing their experiences with individuals with other severe and major mental disorders.

Conclusion

We tried to understand the complexities of living with schizophrenia. The significance and relevance of IPA as a qualitative approach for research with this population can be seen in the findings, which revealed PwS’s desire to be recognized as individuals and live a meaningful life with dignity and respect within the community. These are essential aspects of recovery and community-based rehabilitation. Phenomenological research helps understand the perspectives of vulnerable populations like persons with severe and chronic mental illnesses in-depth and plan person-centered and right-based services (in terms of educational opportunities, vocational training, employment, and social protective measures). It allows clinical researchers to identify the priorities of the individuals living in the community and the barriers to participate in community activities. The findings call for tailor-made recovery-oriented services that need to be designed at individual, family, and community levels to bring systemic change in society. The present study also calls for MHPs and other service providers to adopt person-oriented approaches to practice; develop interventions that focus on positive identity formation and the person’s capabilities, meaning, or purpose in life; provide a potential for growth and development; and promote recovery and effective community reintegration.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest concerning this article’s research, authorship, and publication.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and publication of this article.

References

- 1. Saxena S, Setoya Y. World Health Organization’s comprehensive mental health action plan, 2013–2020. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2014; 68: 585–586.

- 2. Connell J, Brazier J, O’Cathain A, . Quality of life of people with mental health problems: A synthesis of qualitative research. Health Qual Life Outcomes, 2012; 10: 138–154.

- 3. Davidson L, Sells D, Songster S, . Qualitative studies of recovery: What can we learn from the person? In: Ralph RO, Corrigan PW (eds) Recovery in Mental Illness: Broadening Our Understanding of Wellness. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2005, 147–170.

- 4. Borg M, Davidson L. The nature of recovery as lived in everyday experience. J Ment Health, 2008; 17: 129–140.

- 5. Kawachi I, Berkman LF. Social ties and mental health. J Urban Health, 2001; 78: 458–467.

- 6. Patel V, Cohen A, Thara R, . Is the outcome of schizophrenia really better in developing countries?. Braz J Psychiatry, 2006; 28(2): 149–152.

- 7. Lloyd C, King R, Moore L. Subjective and objective indicators of recovery in severe mental illness: A cross-sectional study. Int J Soc Psychiatry, 2010; 56(3): 220–229.

- 8. ****Guy WBRR. Clinical global impression. Assessment manual for psychopharmacology-Revised. Rockville, MD. U.S. Department of Health and Education: National Institute of Mental Health, 1976.

- 9. Smith JA, Shinebourne P. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In: Cooper H, Camic PM, Long DL, . (eds) APA Handbook of Research Methods in Psychology. Volume II: Research designs: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. American Psychological Association, 2012; 73–82.

- 10. Eatough V, Smith JA. Interpretative phenomenological analysis. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology;, 179–194. Sage Publication Ltd, 2008.

- 11. Yardley L Demonstrating validity in qualitative psychology. In: Smith Jonathan A (eds) Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods; 235–251. Sage Publication Ltd, 2008.

- 12. Sedgwick P, Laing RD. Self, symptom and society. Salmagundi, 1971; 16: 5–37.

- 13. Whittemore R, Dixon J. Chronic illness: The process of integration. J Cin Nurs, 2008; 17: 177–187.

- 14. Paterson BL. The shifting perspectives model of chronic illness. J Nurs Scholarsh, 2001; 33: 21–26.

- 15. Kelly M, Gamble C. Exploring the concept of recovery in schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs, 2005; 12: 245–251.

- 16. Min SY, Wong YLI. Sources of social support and community integration among persons with serious mental illnesses in Korea. J Ment Health, 2015; 24: 183–188.

- 17. Muñoz M, Sanz M, Pérez-Santos E, . Proposal of a socio–cognitive–behavioral structural equation model of internalized stigma in people with severe and persistent mental illness. J Psychiatr Res, 2011; 186: 402–408.

- 18. John-Henderson NA, Ginty AT. Historical trauma and social support as predictors of psychological stress responses in American Indian adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Psychosom Res, 2020; 139: 110263.

- 19. Perry W, Heaton RK, Potterat E, . Working memory in schizophrenia: Transient “online” storage versus executive functioning. Schizophr Bull, 2001; 27: 157–176.

- 20. Horan WP, Braff DL, Nuechterlein KH, . Verbal working memory impairments in individuals with schizophrenia and their first-degree relatives: Findings from the Consortium on the Genetics of Schizophrenia. Schizophr Res, 2008; 103: 218–228.

- 21. Mizock L, Russinova Z. Intersectional stigma and the acceptance process of women with mental illness. Women Ther, 2015; 38: 14–30.

- 22. Halsa A. Trapped between madness and motherhood: Mothering alone. Soc Work Ment Health, 2018; 16: 46–61.

- 23. Hudson JL, Moss-Morris R. Treating illness distress in chronic illness. Eur Psychol, 2019; 8: 88–91.

- 24. Narendorf SC, Munson MR, Washburn M, . Symptoms, circumstances, and service systems: Pathways to psychiatric crisis service use among uninsured young adults. Am J Orthopsychiatry, 2017; 87: 585–596.

- 25. Meyer B. Coping with severe mental illness: Relations of the brief COPE with symptoms, functioning, and well-being. J Psychopathol Behav Assess, 2001; 23: 265–277.

- 26. Argentzell E, Håkansson C, Eklund M. Experience of meaning in everyday occupations among unemployed people with severe mental illness. Scand J Occup Ther, 2012; 19: 49–58.

- 27. Chandra PS, Deepthivarma S, Carey MP, . A cry from the darkness: Women with severe mental illness in India reveal their experiences with sexual coercion. Psychiatry, 2003; 66: 323–334.

- 28. Chronister J, Chou CC, Liao HY. The role of stigma coping and social support in mediating the effect of societal stigma on internalized stigma, mental health recovery, and quality of life among people with serious mental illness. J Community Psychol, 2013; 41: 582–600.

- 29. Mueller B, Nordt C, Lauber C, . Social support modifies perceived stigmatization in the first years of mental illness: A longitudinal approach. Soc Sci Med, 2006; 62: 39–49.

- 30. Lynch MA. Optimism, coping, and quality of life in individuals with chronic mental illness; 160–169, Vol. 67. USA: ProQuest Information & Learning Country of Publication, 2006.

- 31. Khalifeh H, Oram S, Osborn D, . Recent physical and sexual violence against adults with severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Rev Psychiatry, 2016; 28: 433–451.

- 32. Benbow S, Forchuk C, Ray SL. Mothers with mental illness experiencing homelessness: A critical analysis. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs, 2011; 18: 687–695.

- 33. Moorkath F, Vranda MN, Naveenkumar C. Lives without roots: Institutionalized homeless women with chronic mental illness. Indian J Psychol Med, 2018; 40: 476–481.

- 34. Moorkath F, Vranda MN, Naveenkumar C. Women with mental illness-an overview of sociocultural factors influencing family rejection and subsequent institutionalization in India. Indian J Psychol Med, 2019; 41: 306–310.

- 35. Gonzales L, Davidoff KC, Nadal KL, . Microaggressions experienced by persons with mental illnesses: An exploratory study. Psychiatr Rehabil J, 2015; 38: 234–241.

- 36. Lundberg B, Hansson L, Wentz E, . Are stigma experiences among persons with mental illness, related to perceptions of self-esteem, empowerment, and sense of coherence?. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs, 2009; 16: 516–522.

- 37. Jochems EC, Mulder CL, van Dam A, . Motivation and treatment engagement intervention trial (MotivaTe-IT): The effects of motivation feedback to clinicians on treatment engagement in patients with severe mental illness. BMC Psychiatry, 2012; 12: 1–7.

- 38. Centorrino F, Hernán MA, Drago-Ferrante G, . Factors associated with noncompliance with psychiatric outpatient visits. Psychiatr Serv, 2001; 52: 378–380.

- 39. Wehmeier PM, Kluge M, Schneider E, . Quality of life and subjective well-being during treatment with antipsychotics in out-patients with schizophrenia. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry, 2007; 31: 703–712.

- 40. Walsh J, Hochbrueckner R, Corcoran J, . The lived experience of schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Soc Work Ment Health, 2016; 14: 607–624.

- 41. Loganathan S, Murthy RS. Living with schizophrenia in India: Gender perspectives. Transcult Psychiatry, 2011; 48: 569–584.

- 42. Ponting C, Delgadillo D, Rivera-Olmedo N, . A qualitative analysis of gendered experiences of schizophrenia in an outpatient psychiatric hospital in Mexico. Int Perspect Psychol, 2020; 9: 159–175.

- 43. Calman L, Brunton L, Molassiotis A. Developing longitudinal qualitative designs: Lessons learned and recommendations for health services research. BMC Med Res Methodol, 2013; 13: 1–10.

- 44. Saldana J. Longitudinal Qualitative Research: Analyzing Change Through Time;, 32–39. Roman & Littlefield Publishers Inc. 2003.