Pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathies are difficult-to-treat pediatric diseases that include drug-resistant seizures often associated with global developmental delays. Among the most common intractable epilepsy syndromes in children are epileptic encephalopathies including Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome is a rare but debilitating and severe encephalopathy characterized by drug-resistant seizures, characteristic electroencephalogram abnormalities, and often progressive and serious cognitive impairment. Although Lennox-Gastaut syndrome often begins in childhood, 80% to 90% of adult patients with Lennox-Gastaut syndrome continue to have refractory seizures and almost all have cognitive impairment. Prognosis is very poor, with progressive disease in adulthood. Dravet syndrome is reported to affect <1 in 40 000 live births with symptom onset generally within the first year of life. Patients with Dravet syndrome develop multiple seizure types, and cognitive deficits and behavioral abnormalities are common, with onset in early childhood. Seizure control through treatment is often partial and transitory. About three-quarters of patients with Dravet syndrome carry a de novo mutation in the SCN1A gene.

Pediatric epilepsy may also accompany other developmental encephalopathies, such as Rett syndrome, the most common cause of severe intellectual disability in females. Rett syndrome is a rare X-linked disorder caused by mutations in the MCEP2 gene that occurs in ∼1:10 000 female births. Among patients with Rett syndrome, the cumulative lifetime risk of developing epilepsy has been reported to be ∼90%, with a common clinical course of seizure occurrence and remission following a remitting and relapsing pattern over the life span.

Among patients with epilepsy, more than one-third develop refractory disease and continue to experience seizures despite stable treatment with antiseizure drug therapy. Likewise, most patients with developmental epileptic encephalopathies are refractory to treatment with antiseizure drugs, and combination therapy is recommended. Treatment strategies focus on reducing seizure frequency to improve quality of life and limiting the impact of adverse events. Benzodiazepines are the cornerstone of rescue therapy for seizure clusters. Diazepam nasal spray (Valtoco) is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the acute treatment of intermittent, stereotypic episodes of frequent seizure activity (ie, seizure clusters or acute repetitive seizures) that are distinct from a patient's usual seizure pattern in patients with epilepsy age ≥6 years. Results of a long-term phase 3 safety study of diazepam nasal spray have been published for both the overall patient population, aged 6-65 years, and the pediatric subpopulation, aged 6-17 years.

This post hoc analysis explored possible differences in long-term safety and effectiveness of diazepam nasal spray to treat seizure clusters in groups of patients with pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathies: a broad group with pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathies and 3 groups with specific diagnoses: Rett syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and Dravet syndrome.

Patients and Methods

Study Design, Participants, and Intervention

Patients with developmental epileptic encephalopathies were the focus of this post hoc subanalysis of a phase 3, open-label, repeat-dose safety study (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier, NCT02721069). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles that have their origin in the Declaration of Helsinki, consistent with Good Clinical Practice guidelines, and all applicable regulatory requirements. Approval of the study protocol and all relevant study documents was obtained from an ethics committee at each study center. All patients or their parents or legal guardians provided written informed consent to participate.

The study methods have been published. In brief, enrolled patients entered a 12-month treatment period, and participation could be extended until study close upon agreement of the caregivers and/or patients, investigators, and study sponsor. Eligible patients aged 6-65 years had a diagnosis of partial or generalized epilepsy and were expected to need benzodiazepine intervention on average at least 6 times per year. The analyses reported here include the group of patients diagnosed with developmental epileptic encephalopathies according to specific criteria (Supplementary Table 1). Along with the larger group of developmental epileptic encephalopathies (n = 64), 3 specific groups of patients (total n = 32) were identified based on a diagnosis of Rett syndrome (n = 16), Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (n = 9), or Dravet syndrome (n = 7).

Caregivers and patients were trained to use diazepam nasal spray. For patients 6-11 years old, doses of 5, 10, 15, or 20 mg were assigned if body weight was 10 to 18 kg, 19 to 37 kg, 38 to 55 kg, or 56 to 74 kg, respectively. For patients ≥12 years old, the same dose levels were assigned according to body weight categories of 14 to 27 kg, 28 to 50 kg, 51 to 75 kg, or ≥76 kg, respectively. In the study, patients could receive a second dose 4 to 12 hours after the first dose, if needed. Dosage and timing of second dose could be adjusted for safety or effectiveness by the investigator.

Study Outcomes and Assessments

The primary purpose of this study was to assess the safety of diazepam nasal spray, including the assessment of treatment-emergent adverse events and treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse events. Proxy assessments of treatment effectiveness included the proportion of treated seizure clusters in which a second dose of nasal spray was administered within 24 hours of the first dose (exploratory analysis) and the study retention rate. Results were summarized using descriptive statistics.

Results

Patient Demographics

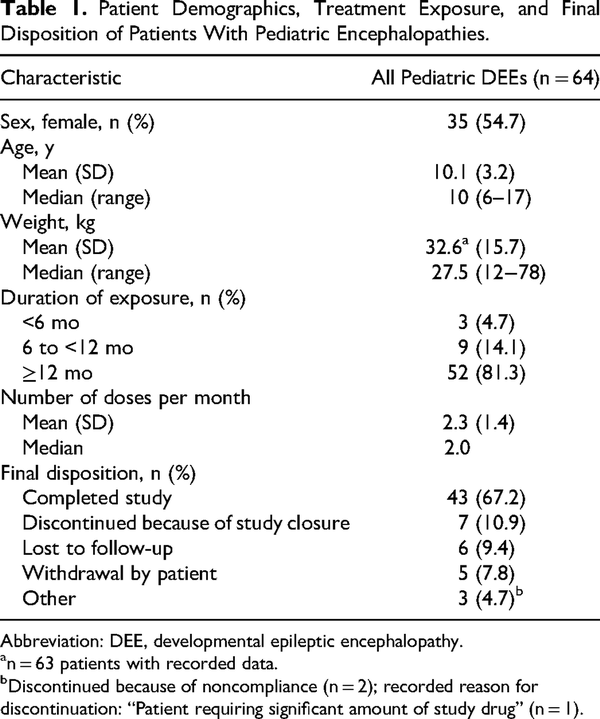

Of the 175 patients enrolled in the study, 163 received at least 1 dose of diazepam nasal spray, including 64 pediatric patients (aged 6-17 years) diagnosed with developmental epileptic encephalopathies (Table 1). Small groups of patients with the following specific diagnoses were identified: 16 patients had a diagnosis of Rett syndrome (16 pediatric patients, no adults), 9 had a diagnosis of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (7 pediatric patients, 2 adults aged ≥18 years), and 7 had a diagnosis of Dravet syndrome (6 pediatric patients and 1 patient aged 18 years).

Diazepam Nasal Spray Administration

The majority of patients had ≥12 months exposure to the study drug (Table 1), with a median number of approximately 2 doses per month.

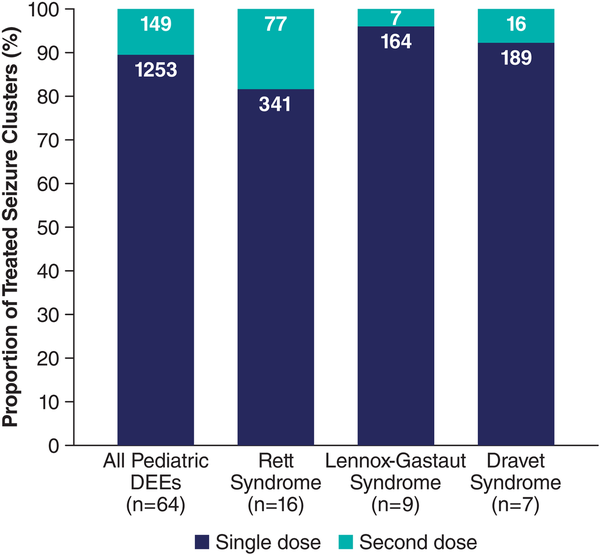

A total of 1402 seizure clusters were treated in the broad pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathy group (Figure 1). In the groups with specific diagnoses, there were 418 treated seizure clusters in the Rett syndrome group, 171 in the Lennox-Gastaut syndrome group, and 205 in the Dravet syndrome group. The proportions of seizure clusters administered a second dose within 24 hours was 10.6%, 18.4%, 4.1%, and 7.8%, respectively.

Figure 1

Seizure clusters treated with a single dose or an initial plus second dose of diazepam nasal spray in patients with developmental epileptic encephalopathies. DEE, developmental epileptic encephalopathy.

By study end, a large majority of patients in each group had completed the study or were ongoing at time of study closure: 78.1%, 81.3%, 77.8%, and 100% for the broad pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathy, Rett syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and Dravet syndrome groups, respectively.

Safety and Tolerability

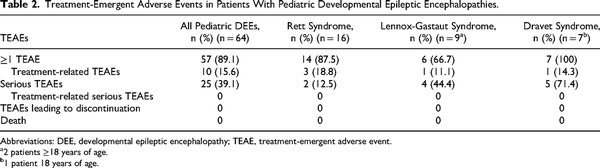

Treatment-emergent adverse events, irrespective of relationship to study drug, were common in patients with developmental epileptic encephalopathies in this long-term study (Table 2). Serious treatment-emergent adverse events were less frequently reported in patients with Rett syndrome and more frequently reported in patients with Dravet syndrome than the other groups. There were no reports of respiratory depression in the study safety population. No patients in these groups discontinued because of a treatment-emergent adverse event.

Besides seizure, the most common treatment-emergent adverse events reported by ≥10% of patients in the broad pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathy group were nasopharyngitis (21.9%), pyrexia (20.3%), upper respiratory tract infection (15.6%), influenza (14.1%), pneumonia (12.5%), constipation (10.9%), and vomiting (10.9%). Somnolence, irrespective of relationship to study drug, was reported in 6 (9.4%) of the patients.

Treatment-emergent adverse events deemed at least possibly related to treatment occurred in 15.6%, 18.8%, 11.1%, and 14.3% of patients in the broad pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathy, Rett syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and Dravet syndrome groups, respectively. The only treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse event occurring in >1 patient was epistaxis (n = 2). Most other treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse events were associated with the route of administration (ie, dysgeusia, nasal discomfort, nasal mucosal disorder, rhinorrhea, eye irritation, tonsillar hypertrophy). No serious treatment-emergent adverse events were deemed possibly or probably related to diazepam nasal spray.

Discussion

In this analysis of groups of patients with developmental epileptic encephalopathies from the long-term, phase 3, safety study of diazepam nasal spray, the rates of treatment-emergent adverse events support the safety of diazepam nasal spray across multiple pediatric populations with developmental epileptic encephalopathies, including patients with Rett syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and Dravet syndrome. Treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse events were consistent with those reported in the overall study and were generally mild or moderate in severity. No patients in these groups discontinued the study because of treatment-emergent adverse events.

The rates of treatment-emergent adverse events were generally similar between the patients in the broad pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathy group (89.1%), the 3 specific syndrome groups (66.7%-100%), the previously published results of the larger group of all pediatric patients in the study (87.2%), and the overall study population (82.2%). Rates of serious treatment-emergent adverse events were also similar between the broad pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathy group (39.1%) and the entire pediatric study population (35.9%) and the overall study population (30.7%), even though these groups with severe disease might have been expected to report elevated rates. Patients with Dravet syndrome reported higher rates of serious treatment-emergent adverse events, which may be influenced by the severity of their disease, the small number of patients in the group, or another factor. The only treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse event reported by >1 patient was epistaxis, occurring in 2 patients in the broad pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathy group. Other single-report treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse events were predominantly related to the intranasal route of administration. No serious treatment-emergent adverse events were considered treatment-related. No respiratory depression events were reported among this patient subpopulation or the broader patient study population, which aligns with previous findings following intranasal diazepam administration.,

The safety profile of benzodiazepine rescue therapies in pediatric populations is not well described, and this post hoc analysis represents one of the first attempts to characterize safety in pediatric patients with severe disease. Safety and efficacy of diazepam rectal gel were examined in a pediatric cohort (aged 2-17 years) of 68 patients with acute repetitive seizures receiving diazepam rectal gel derived from 2 randomized controlled trials., The most common treatment-emergent adverse event was somnolence, reported in 17 of 68 patients (25%), which is somewhat higher than the rates (irrespective of relationship to treatment) reported here for the broad pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathy group (9.4%) and in the overall pediatric population (9.0%). In clinical studies of intranasal midazolam in seizure clusters, only 18 of the 292 patients (6.2%) in the test-dose phase were aged 12-17 years (with 5 randomized to active treatment), with patients younger than 12 years, with status epilepticus due to cluster progression, or with progressive neurologic disease excluded from the study. Safety and efficacy data were not reported separately for this small subgroup.

The high percentage of seizure clusters treated with a single dose suggests initial-dose effectiveness in these highly treatment-resistant groups. The rates in the 4 groups (81.6%-95.9%) were comparable to the rates observed in the entire pediatric group (88.6%) and the overall study population (87.4%,) in the 24 hours after the initial dose. In a separate analysis of benzodiazepine rescue therapies more broadly, 94.2% of seizure clusters treated with diazepam nasal spray in clinical trials required no second dose for seizure control at 6 hours, compared with 61.5% of seizure clusters treated with intranasal midazolam, which could potentially affect health care utilization. At 12 hours, 77% of patients receiving rectal diazepam did not have a second seizure, whereas single doses of diazepam nasal spray were used in 91.7% of seizure clusters. At 24 hours, data were not available for the midazolam or rectal diazepam formulations.

The results of second-dose utilization of diazepam nasal spray, a surrogate measure of effectiveness, among patients with pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathies is reinforced by the high retention rates up to study closure in this long-term study (77.8%-100% across groups), similar to rates observed in the pediatric group (78.2%) and the overall study (76.1%). In addition, data from the larger study group show that the median time from administration to seizure cessation was 4 minutes (range: 1-1151 minutes), and time to cessation was 11 minutes at the 75th percentile. Finally, this data set has been used to evaluate a novel metric for effectiveness of intermittent therapy, the time between 2 treated seizure clusters, named SEIzure interVAL (or SEIVAL). In the published analysis, a consistent cohort of pediatric (aged 6-17 years) patients (n = 32) with treated seizure clusters in each of four 90-day periods over the course of a year saw a significant increase in mean SEIVAL from 13.0 days to 25.9 days (P = .02) across 360 days. These findings support a lack of tolerance to diazepam nasal spray over time, and more interestingly, open new research avenues into the potential impact of diazepam nasal spray on the natural course of seizure clusters.

Patients with pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathies often represent a difficult-to-treat population with severe disease, and these results show that diazepam nasal spray provides patients with encephalopathies levels of safety and effectiveness similar to other patients with seizure clusters and provides an important, easy-to-administer therapeutic option for patients and caregivers. In addition, previously published analyses showed no influence of concomitant clobazam use, a daily adjunctive therapy for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, on the safety or effectiveness profiles of diazepam nasal spray in pediatric patients.

Limitations of the long-term safety study, including the lack of a control group, are provided in the primary publications., Similarly, treatment effects are difficult to characterize given the open-label study design without comparator arm and small subgroup sizes. However, these findings from a real-world setting are consistent with what is already known about this well-characterized molecule.

Conclusion

In this post hoc analysis of a long-term safety study of patients with pediatric developmental epileptic encephalopathies, the safety profile of repeated intermittent doses of diazepam nasal spray as rescue therapy was consistent with that of the larger pediatric study population (aged 6-17 years) and the full study population (aged 6-65 years) with seizure clusters. Moreover, analysis of groups with specific encephalopathies, Rett syndrome, Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and Dravet syndrome, identified no additional safety concerns, and no patients discontinued the study owing to treatment-related treatment-emergent adverse events. These data support the use of diazepam nasal spray in a broad range of pediatric populations (aged ≥6 years), including patients with severe disease.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support, under the direction of the authors, was provided by David McLay, PhD, of The Curry Rockefeller Group, LLC (Tarrytown, NY), in accordance with Good Publication Practice (GPP4) guidelines and was funded by Neurelis, Inc. (San Diego, CA).

Author Contributions All authors contributed to conception, design, analysis, and interpretation of results as well as revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript for submission to Journal of Child Neurology.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr Tarquinio has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Avexis, Marinus, and Neurelis, Inc. Dr Wheless has served as an advisor or consultant for CombiMatrix; Eisai; GW Pharmaceuticals; Lundbeck; Neurelis, Inc.; NeuroPace; Supernus Pharmaceuticals; and Upsher-Smith Laboratories. Dr Wheless has served as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for Cyberonics; Eisai; Lundbeck; Mallinckrodt; Neurelis, Inc.; Supernus Pharmaceuticals; and Upsher-Smith Laboratories and has received grants for clinical research from Acorda Therapeutics; GW Pharmaceuticals; Insys Therapeutics; Lundbeck; Mallinckrodt; Neurelis, Inc.; NeuroPace; Upsher-Smith Laboratories; and Zogenix. Dr Segal has received personal compensation for consulting, serving on a scientific advisory board, speaking, or other activities with Eisai, Encoded Therapeutics, Epitel, Greenwich, Lundbeck, Novartis, Nutricia, and Qbiomed and is an advisor for Neurelis, Inc. Dr Misra was an employee of and has received stock options from Neurelis, Inc. Dr Rabinowicz is an employee of and has received stock options from Neurelis, Inc. Dr Carrazana is an employee of and has received stock and stock options from Neurelis, Inc.

Funding The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by Neurelis, Inc. (grant number N/A).

ORCID iD James W. Wheless https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4735-3431

Supplemental Material Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Moon JU, Cho KO. Current pharmacologic strategies for treatment of intractable epilepsy in children. Int Neurourol J. 2021;25(suppl 1):S8–S18. doi:10.5213/inj.2142166.083

- 2. Jahngir MU, Ahmad MQ, Jahangir M. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: in a nutshell. Cureus. 2018;10(8):e3134. doi:10.7759/cureus.3134

- 3. Bourgeois BF, Douglass LM, Sankar R. Lennox-Gastaut syndrome: a consensus approach to differential diagnosis. Epilepsia. 2014;55(suppl 4):4–9. doi:10.1111/epi.12567

- 4. Dravet C. The core Dravet syndrome phenotype. Epilepsia. 2011;52(Suppl 2):3–9. doi:10.1111/j.1528-1167.2011.02994.x

- 5. Tarquinio DC, Hou W, Berg A, et al. Longitudinal course of epilepsy in Rett syndrome and related disorders. Brain. 2017;140(2):306–318. doi:10.1093/brain/aww302

- 6. Chen Z, Brodie MJ, Liew D, Kwan P. Treatment outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed epilepsy treated with established and new antiepileptic drugs: a 30-year longitudinal cohort study. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(3):279–286. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.3949

- 7. Jafarpour S, Hirsch LJ, Gainza-Lein M, Kellinghaus C, Detyniecki K. Seizure cluster: Definition, prevalence, consequences, and management. Seizure. 2019;68:9–15. doi:10.1016/j.seizure.2018.05.013

- 8. Neurelis, Inc. VALTOCO® (diazepam nasal spray). Full Prescribing Information. Neurelis, Inc.; 2023.

- 9. Wheless JW, Miller I, Hogan RE, et al. Final results from a phase 3, long-term, open-label, repeat-dose safety study of diazepam nasal spray for seizure clusters in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2021;62(10):2485–2495. doi:10.1111/epi.17041

- 10. Tarquinio D, Dlugos D, Wheless JW, Desai J, Carrazana E, Rabinowicz AL. Safety of diazepam nasal spray in children and adolescents with epilepsy: results from a long-term phase 3 safety study. Pediatr Neurol. 2022;132:50–55. doi:10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2022.04.011

- 11. Hogan RE, Tarquinio D, Sperling MR, et al. Pharmacokinetics and safety of VALTOCO (NRL-1; diazepam nasal spray) in patients with epilepsy during seizure (ictal/peri-ictal) and nonseizure (interictal) conditions: a phase 1, open-label study. Epilepsia. 2020;61(5):935–943. doi:10.1111/epi.16506

- 12. Tanimoto S, Pesco Koplowitz L, Lowenthal RE, Koplowitz B, Rabinowicz AL, Carrazana E. Evaluation of pharmacokinetics and dose proportionality of diazepam after intranasal administration of NRL-1 to healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Drug Dev. 2020;9(6):719–727. doi:10.1002/cpdd.767

- 13. Kriel RL, Cloyd JC, Pellock JM, Mitchell WG, Cereghino JJ, Rosman NP. Rectal diazepam gel for treatment of acute repetitive seizures. The North American Diastat Study Group. Pediatr Neurol. 1999;20(4):282–288. doi:10.1016/s0887-8994(98)00156-8

- 14. Cereghino JJ. Identification and treatment of acute repetitive seizures in children and adults. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2007;9(4):249–255. doi:10.1007/s11940-007-0011-8

- 15. Dreifuss FE, Rosman NP, Cloyd JC, et al. A comparison of rectal diazepam gel and placebo for acute repetitive seizures. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(26):1869–1875. doi:10.1056/NEJM199806253382602

- 16. Detyniecki K, Van Ess PJ, Sequeira DJ, Wheless JW, Meng TC, Pullman WE. Safety and efficacy of midazolam nasal spray in the outpatient treatment of patients with seizure clusters—a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Epilepsia. 2019;60(9):1797–1808. doi:10.1111/epi.15159

- 17. Rabinowicz AL, Faught E, Cook DF, Carrazana E. Implications of seizure-cluster treatment on healthcare utilization: use of approved rescue medications. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2022;18:2431–2441. doi:10.2147/ndt.S376104

- 18. Wheless J, Peters J, Misra SN, et al. Comment on “Intranasal midazolam versus intravenous/rectal benzodiazepines for acute seizure control in children: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Epilepsy Behav. 2022;128:108550. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2021.108550

- 19. Misra SN, Sperling MR, Rao VR, et al. Significant improvements in SEIzure interVAL (time between seizure clusters) across time in patients treated with diazepam nasal spray as intermittent rescue therapy for seizure clusters. Epilepsia. 2022;63(10):2684–2693. doi:10.1111/epi.17385