The onset of menstruation, or menarche, is a critical moment in the developmental lives of adolescent girls, often laden with physical, psychological and sociocultural implications (; ; ). In this paper, we use the term “adolescent girl” to refer to cisgender girls in the process of developing from a child into an adult. Early menstrual experiences in adolescence are often marked by a lack of knowledge about the physiological aspects of the menstrual cycle, and practical guidance on managing monthly blood flow (; ; ). This absence of knowledge, along with insufficient support, can lead girls to experience menarche negatively, including poor attitudes about menstruation and menstrual distress (; ; ; ). Many adolescent girls at menarche are also introduced to “menstrual etiquette,” or behavioral expectations related to “acceptable” period management practices (e.g., not revealing one’s menstrual status to others) (); notions which may be reinforced by families, teachers and peers (; ). These expectations often originate from ongoing menstrual stigma, including that periods are “dirty” and something to be ashamed of (; ; ; ). Such social norms can negatively impact a girl’s confidence, mental health and willingness to seek out social support from peers, families or schools (; ).

There is growing evidence around the world highlighting the ways in which school environments specifically fail to meet the needs of menstruating adolescent girls (; ; ). Poor access to menstrual products, insufficient menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) education and a lack of supportive bathrooms for period management have all been identified as challenges; each of which can negatively impact the health and well-being of adolescent girls (; ; ). The term “bathroom,” as used in this paper, refers to sanitation spaces which house both toilets and handwashing facilities. Bathrooms, in particular, remain a key overlooked issue across menstruation-focused policies, programs and advocacy efforts globally, despite their well-documented role in exacerbating girls’ anxieties and challenges around period management during the school day (; ; ; ; ).

Menstruating adolescent girls have unique sanitation needs as compared to their non-menstruating peers, including the need to visit bathrooms more often or for longer lengths of time when managing their periods. Barriers to the timely changing of menstrual products during the school day can result in the staining of clothing with blood; an occurrence which generates feelings of shame and embarrassment, or lead to teasing (; ; ; ). Global evidence suggests that fears of stains and teasing may hinder adolescent girls’ ability to concentrate in the classroom (; ; ). Further, many adolescents experience unpredictable, prolonged or heavy menstrual bleeding following menarche (; ; ), which further increases their bathroom needs. In the United States of America (U.S.A.), however, there remains insufficient evidence on the menstruation-related experiences of adolescent girls in educational settings, especially girls from low-income backgrounds (; ; ) or those attending schools that are poorly funded or have aging building infrastructure.

Despite the central role of bathrooms for period management, there has been little exploration of how these spaces, coupled with school policies regulating their usage, impact the menstrual experiences of adolescents in the U.S.A. This includes how the physical design of bathrooms, including toilet stalls, can pose practical challenges for menstruating users. For example, grey literature indicate that wide gaps between toilet stall doors, which reduce privacy by enabling others to peer inside, are a common feature in many American bathrooms (; ; ); an issue that is particularly problematic for menstruating users (). Middle school and university dormitory bathrooms have also been found to lack design measures to support period management, including menstrual waste receptacles (; ) and dispensers providing convenient access to menstrual products (; ). A 2018 survey of 362 school nurses covering elementary, middle and high schools across the U.S.A., found that 75% of school bathrooms were not well-stocked with menstrual products (). Poor maintenance of school bathrooms, including broken toilets and overflowing trash bins, have also been found in many low-income schools; issues which may reduce a student’s ability to comfortably change or dispose of a menstrual product while in school (; ).

The policies regulating students’ access to bathrooms have also been identified as an issue. Many schools discourage students from visiting bathrooms during class time (). However, almost 25% of school nurses working in American high schools surveyed in 2017 reported that students lack sufficient time to visit bathrooms between classes (); another issue found to be more exigent for menstruating students (). Lastly, social activities, such as group vaping or the recording of social media content, are increasingly taking place in school bathrooms (; ), and thus may have a detrimental impact on students’ comfort using these facilities for purely sanitation-related purposes, such as managing their period.

In recent years, there has been growing political momentum to tackle menstruation issues across the U.S.A. This is evidenced by new city- and state-level “menstrual equity” policies; the majority seeking to provide free menstrual products to select low-income populations, including students. At least 20 U.S.A. states have passed legislation aimed at addressing period poverty, with most measures focused on providing free menstrual products for low-income girls attending middle and high schools (; ). Although such policies are an important step forward, they overlook key aspects of period management in schools, such as the provision of menstrual health information and the accessibility and design of bathrooms. The latter issue may be graver in low-resource school systems, as they typically have poorer quality facilities and infrastructure. This paper seeks to highlight the specific issue of school bathrooms through examining how the physical and social environments of these facilities, coupled with policies regulating their usage, can shape girls’ experiences with menstruation during the school day.

This study utilizes a theoretical framework developed by Hennegan et al. aimed at examining girls and women’s menstrual experiences (). The integrated model of menstrual experience explores the roles of socio-cultural factors, social support systems (e.g., schools, families, peers), behavioral expectations and menstrual health knowledge in shaping a girl or women’s menstrual experience, positively or negatively. This includes better understanding how a negative menstrual experience may hinder a menstruating girl’s ability to participate in school and other social activities and any implications it may have on their physical and mental health. One of the key antecedents utilized by this model is “resource limitations,” including the physical environment. Both school bathrooms and menstrual product disposal facilities are key physical environment components given their role in supporting girls with undertaking a range of menstrual-related tasks throughout the day. This includes serving as spaces for changing products, washing and drying materials, cleaning their hands and body and locations for product disposal.

Methods

Research Design

This qualitative and participatory study was adapted from a previously used research methodology conducted with adolescent girls in Baltimore, U.S.A. () and numerous low-and-middle income (LMIC) countries (, 2015, 2020; Mumtaz et al., 2019). Data collection methods included: (1) Participatory Methodologies (PM) sessions with cisgender adolescent girls aged 15 to 19; (2) In-depth interviews (IDI) with cisgender adolescent girls aged 15 to 19, and (3) Key Informant Interviews (KII) with adults interacting in girls’ daily lives, such as teachers, guidance counselors, coaches, healthcare workers and religious leaders. Older adolescent girls were purposively sampled given their ability to reflect on the experience of puberty, including their menstruation experiences and recommendations.

Research Setting

The research sites included the three most populous and ethnically diverse U.S.A. cities: New York City (NYC), Los Angeles (LA) and Chicago (). Each of these cities has high levels of poverty, illustrated by 19.5% of NYC residents (), 19.1% of LA residents (), and 12.4% of Chicago residents living below the poverty line (). In addition, all three of these cities has large, funding challenged public school systems, with such disparities often exacerbated across demographic and racial lines (; ).

Sample and Recruitment

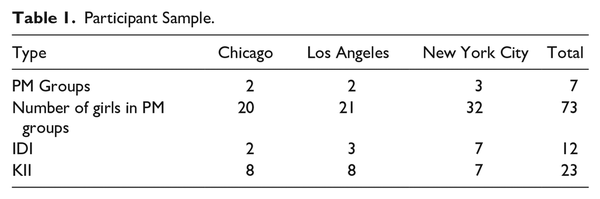

Across the three cities, a total of 73 adolescent girl participants (15–19 years old) were involved in the PM sessions (see Table 1). IDIs with additional adolescent girls (n = 12) were conducted using a semi-structured questionnaire. All participants (IDI and PM groups) were recruited directly through local partners, including school administrators or teachers from public and charter school institutions, or through staff working at local youth-serving non-profits. Adolescent girls were purposively sampled to ensure a diversity of experiences, including different ethnic, racial, geographic, and educational backgrounds. Given that participants came from a range of educational institutions (current and previously attended), they were asked to share generalized observations and perspectives from across their schooling experiences. Although participants who experience menstruation were intentionally sampled, young people were not asked to self-report their menstruating status during the research as we did not want to inadvertently create discomfort if the young person had not publicly identified their gender identity. The PM sessions participant demographics were 52% Black, 44% Latina and 4% other. Despite recognizing the importance of Black and Latina girls unique lived experiences growing up in the U.S.A., findings generated from this study cannot be attributed to individual participants of a specific race or ethnicity due to the participatory data collection process utilized.

The KIIs with adults (n = 23) were also purposively recruited from a range of professions and organizations that directly interact with low-income adolescent girls in each of the three cities. KIIs participants were recruited directly from the schools or non-profits involved in the PM groups or through recommendations from colleagues, which was primarily due to their professions and/or unique expertise (e.g., adolescent pediatricians, school nurses, sports coaches, religious leaders). Seven of the KIIs worked at the organizations or schools where girls were recruited from for the PM sessions.

The findings shared in this paper are derived from the three following data sources:

PM sessions: Groups of 8 to 10 girls were gathered in each city in a confidential space for 1.5-hour sessions. Each PM group met three times over a 2 to 3-week period. On average, the PM sessions had a high retention rate (~80%) over the course of all three sessions. The PM sessions included a range of activities with the results in this paper derived from three specific activities and fieldnotes. These include (a) First Period Stories Activity: Girls anonymously wrote personal narratives describing their first menstrual experiences, including how they reacted, how they coped, what they wished they had known prior to that experience, and their advice for younger girls; (b) Girl-Friendly Schools Brainstorm: In small groups, girls were asked to brainstorm how they would make their school environments more girl-friendly, including more period supportive, with an imaginary $1 million improvement budget; and (c) Draw a Girl-Friendly Bathroom: Girls were individually asked to draw and annotate what an ideal girl-friendly bathroom in schools would look like.

IDIs: We utilized semi-structured interview guides which allowed for an in-depth examination of girls’ experiences, including questions which explored girls’ interactions with the physical and social aspects of their schools’ environments when menstruating, how their relationships with their classmates and teachers impacted their period experiences, and recommendations on how to improve bathroom environments and policies.

KIIs: We utilized semi-structured interview guides for the adults in girls’ lives that sought to identify perspectives on the body and development issues facing adolescent girls, including how school environments, policies and other societal factors impacted girls’ experiences with menstruation and their changing bodies.

Data Collection

The data collection team included three cisgender women research staff from (blinded) and three cisgender women data collection assistants. Prior to the data collection, the team conducted reflexivity exercises, considering our positionality in relation to the power dynamics of the research process, and reviewed our own current and previous experiences as menstruators. All PM and IDIs were conducted in private settings (e.g., school classrooms or non-profit offices). The KIIs were also conducted in private locations, or via video conferencing platforms (FreeConferenceCall.com) or phone. All data collection activities (PM, IDIs, and KIIs) were conducted in English. To ensure the comfort of participants, tape-recording was not used for the PM groups. Instead, careful notetaking was utilized, including the capturing of verbal and non-verbal responses. All IDIs and KIIs were recorded and transcribed. Parental consent was acquired for all of the adolescent girl PM and IDI participants under 18 years of age, who themselves provided assent. All participants 18 years of age or older provided informed consent. All study procedures were approved by the Columbia University Medical Center Institutional Review Board and the New York City Department of Education Institutional Review Board.

Data Analysis

The research analysis team, which was comprised of three research team members, reviewed all transcripts, PM drawings, and fieldnotes. Analysis was performed using Malterud’s “systematic text condensation,” a descriptive and explorative method for conducting qualitative thematic analysis of different types of qualitative data (). This approach utilizes sequential steps, which includes (a) broad impression (a review of the entirety of data), (b) identification of the key themes (distilling themes into codes), (c) condensing the text from the code and exploring meaning (reduction of data into a few meaningful code groups), and (d) synthesizing (building credible narratives which illuminate the study questions). Key themes identified were then disseminated to the wider research team for further discussion, validation, and consensus-building.

Results

Four major themes were identified about how school bathrooms may negatively impact girls’ menstruation experiences while in school. They include: (1) secrecy and embarrassment related to bathroom usage while menstruating; (2) discomfort surrounding bathroom social environments; (3) bathroom design and maintenance challenges; and (4) school bathroom policies as a barrier to access.

Secrecy and Embarrassment Related to Bathroom Usage While Menstruating

Across all three cities, adolescent girls indicated experiences of embarrassment or discomfort when needing to visit bathrooms during the school day to change their menstrual products. This often led to the adoption of secrecy practices, such as hiding menstrual products within their clothing or in a small bag to reduce the risk of others discovering their menstruating status. One adolescent girl from NYC explained this tension:

. . .I would take the pad with me, but I wouldn’t bring my bookbag because everyone would be like ‘hey you’re on your period?’ or ‘why are you taking your bag?’. . . so, I’d just grab my pad. One time I didn’t have my little bag [for hiding the pad] when going to the bathroom. . .so I’d put it in my sweater or my pants and my friends would be like, ‘why are you being so sneaky?’. . .

The menstrual stigma revealed by these secrecy practices suggests that many girls have discomfort not only with their peers knowing their period-related reason for visiting the bathroom, but also teachers and school staff. Girls often need to request permission to visit the bathroom during class to change a menstrual product, and numerous girls shared their anxiety surrounding this task. One Chicago non-profit coordinator described the intersection of girls’ hesitancy with existing school bathroom policies:

. . .[girls] were getting embarrassed about having to go to the bathroom and carrying in something [a pad]. Or having to keep the secrecy concept. . .having to ask for the hall pass to go to the bathroom is something girls never want to do.

Many girls confirmed having such discomfort when asking their teachers to use the bathroom. They also explained how the actual process of asking permission made them particularly vulnerable to disclosing their period status in front of their peers. An adolescent girl in LA described her anxiety with this task, explaining how “it was embarrassing. . .I was like in the back of the class and I had to walk to the front and whisper it to her [the teacher] and then she couldn’t hear me, so I had to say it a little louder.” Such episodes were described as even more embarrassing when they involved interactions with male teachers. In some cases, this discomfort resulted in girls refraining from going to the bathroom at all, even when needing to change a menstrual product. As one adolescent girl during a participatory session in LA explained, “I just hold it in and then lower my backpack and hope I don’t stain; then at lunch I go to the bathroom.” Delaying behaviors, however, were described as increasing the potential for menstrual stains, which numerous girls described as a potentially embarrassing incident.

Discomfort Surrounding Bathroom Social Environments

Girls across all three cities indicated that school bathrooms were popular locations for socializing, likely an outcome of their relative privacy within school environments. This social congregation, however, often exacerbated girls’ discomfort when using toilet facilities, especially when managing their period. Girls across all three cities described a range of social activities that often occurred in school bathrooms, including groups of students vaping (e.g., the use of e-cigarettes), smoking, talking or recording social media content. These activities, which happened directly outside of or inside toilet stalls, made girls inside neighboring stalls anxious, with particular worries about others hearing them change their menstrual product or unwrap a menstrual pad. As one adolescent girl in LA explained during an interview:

. . .there is a lot of people vaping in the bathroom, so they’ll take up the big stalls. Normally it’s groups of like 10 girls. . .and they’ll all just vape. Just using the bathroom in general is uncomfortable so when you’re on your period you’re always like, “do I really want to go in there?”. . .

Across all three cities girls complained about the noise associated with changing menstrual products, especially the wrappers for menstrual pads. During an interview, an adolescent girl in NYC described her discomfort: “when you open a pad, it’s like so loud that now everyone knows ‘I have my period!’” Notably, when conducting the “draw a girl-friendly bathroom” participatory activity, groups of girls in both Chicago and LA indicated a desire to have background music playing in school bathrooms to specifically distract from the product wrapper noise. It was also suggested by a number of girls that taller or thicker bathroom stall doors and walls, similar to the toilet stalls often found in movie theaters, could help to reduce these noise concerns.

In some instances, girls described adopting coping strategies to avoid the uncomfortable social environments found in bathrooms, including preferences for single-use bathrooms when available. A school-based social worker in LA explained how “many students come to use the bathroom in the health office, and I think it’s just because they felt like there wasn’t any privacy [in other bathrooms].” Girls across the three cities echoed this sentiment, complaining about the lack of privacy they felt inside communal school bathrooms. The reasons girls cited included an insufficient number of stalls and the close proximity of many bathrooms to social congregation locations (e.g., cafeterias); which led to longer lines and more crowding, and thus less private, bathroom environments.

Bathroom Design and Maintenance Challenges

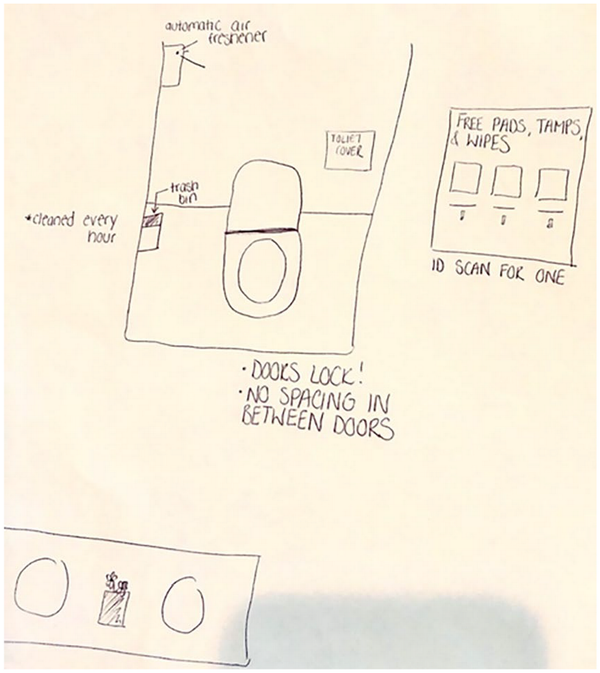

Across all three cities, girls indicated numerous physical design challenges which make bathrooms uncomfortable, especially while menstruating. During the “draw a girl-friendly bathroom” participatory activity, girls identified a series of factors which contributed to negative bathroom experiences, along with aspects they would like to see improved (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

An example of girl-friendly bathroom drawing developed by an adolescent girl in Chicago, U.S.A.

Numerous girls described how wide gaps between stalls, coupled with short stall door lengths, often resulted in others being able to peer into the toilet cubicle while they were inside. An adolescent girl in Chicago complained about the short bathroom stall doors and how they made her feel exposed, explaining: “we need a cover over the top because people like to play games and look over the top into a toilet stall. . . we just need taller stalls.” Teachers and school staff also observed the poor design of many bathrooms, explaining how many of the schools were located in older buildings, which often lacked sufficient ventilation or windows. As a former middle school assistant principal from NYC explained:

. . .just the way that they are set up. . .there’s like very little ventilation and sometimes the doors are not even like full height. . .you don’t really feel like you have a lot of privacy. . . it makes it really difficult to even use. . .it was not a super pleasant experience. . .

Girls also indicated privacy issues stemming from poorly functioning locks on stall doors. During the participatory groups, an adolescent girl in Chicago explained: “doors should have two locks; I feel like they always break and then we don’t have locks. . .people are always walking in on me and it is very stressful.” Across all three cities, girls identified a range of privacy concerns in school bathrooms, noting how improvements, as exemplified in Figure 1, would greatly enhance not only their comfort in dealing with their periods but their overall sanitation privacy.

Another design challenge emerged around the disposal of used menstrual products. Many girls complained about the inconsistent presence of trash bins for product disposal in school bathrooms. This includes trash bins or product disposal units located inside toilet stalls, or communal trash bins within the larger bathroom premises. One adolescent girl in NYC described her frustration, explaining: “there is nowhere inside the stall for disposing of used materials. You would have to flush it down the toilet. I bring a plastic bag with me, wrap it around and put it in the outside garbage [bin].” The latter meant potentially “outing” the menstruating status of a given girl. Almost all of the participants indicated a preference for the placement of menstrual disposal bins directly inside toilet stalls for improved period management privacy. Such measures might also reduce the menstrual products being directly flushed down toilets, which causes plumbing problems, as described by some school administrators, especially in older school buildings. Numerous girls mentioned that the general uncleanliness of school bathrooms, including overfull trash bins and clogged toilets, further contributed to their discomfort when using bathrooms while menstruating.

A final environmental design found to be problematic for some girls was the location of emergency menstrual products (e.g., for an unexpected period). Many schools’ policies required a girl to visit a school administrator or nurse to request a menstrual product, prior to visiting the bathroom for changing. This extra step for accessing a product resulted in them missing more class time, which concerned some students. One adolescent girl in NYC explained this tedious experience:

. . .in my schools. . .they don’t have products anywhere, so you have to go down to the nurse to get a pad. They take you to a back room and then [she] ask you lots of questions and then they will finally give you a pad. . .

Some girls indicated preferring to ask their peers for products in the event of a menstrual emergency, rather than going through school gatekeepers, as it was oftentimes easier and faster. The majority of girls across all three cities indicated the absence of menstrual product dispensers, free or for charge, directly inside school bathrooms. However, there was strong consensus among girls, that there would be many advantages to having period products available inside bathrooms. This would enhance period management privacy, with less people observing a girl’s movement to acquire a product within the school and reduce the amount of missed class time required for procuring a product.

School Bathroom Policies as a Barrier to Access

Across all three cities, girls, teachers and school staff shared various bathroom policies used to regulate toilet access by students. Schools exhibiting stricter bathroom policies described the rationale for these practices, including student safety concerns, such as issues of bullying and violence, coupled with heightened incidents of vaping and substance use; all activities which often occurred within bathroom spaces. One adolescent girl in LA described her school’s approach to reduce misuse:

. . .Since people vape in the restroom, now you need the key from the office. They open the restroom and now you have to sign in and sign out. They time you when you are in there. If it takes more than 5 min, they start knocking. . .

Numerous girls indicated frustration with the regulations surrounding their bathroom usage, especially when dealing with their periods. Some schools utilized even more severe measures to regulate bathrooms, such as locking toilet facilities during class periods. This practice resulted in short, concentrated time allotments for all student bathroom usage, and thus a higher frequency for lines during designated class breaks and lunch periods. A former middle school teacher from NYC explained observing issues of overcrowding in female bathrooms, describing: “you’re going in between classes when everyone else is going. . . some of those policies can make it more uncomfortable for young women.” Other school policies included bathroom pass quotas, in which students were given a limited number of bathroom passes each day or week. During the participatory activities, a Chicago-based adolescent girl explained the challenges she faced with quota practices while menstruating:

. . .At my school you have a certain amount of bathroom passes and if you run out then you can’t go to the bathroom. So, if you are on your period and go the bathroom every 3 hours like I do, then you don’t have enough passes to change throughout the day. . .

Adolescent girls that experience heavier menstrual bleeding may require changing menstrual products more frequently, making regulated one-size-fits-all approaches for bathroom access problematic. During an interview, an adolescent girl in LA described her anxiety around managing her heavy periods:

. . .I have a super heavy flow. . . my first 3 days are super heavy. I have to change it like every 30 mins. . .sometimes I get too scared to ask to go to the bathroom cause they [teachers] are like “finish this work” . . .and I’m like: ‘I can’t, my period is going to overflow. My pad cannot hold this’. . .

Although heavy bleeding created an increased sense of urgency for accessing bathrooms, many participants indicated the larger challenge to be the discomfort in providing teachers and school staff with reasons for frequent or pressing bathroom trips. Some girls feared getting in trouble for requesting increased access; others described situations in which school administration used negative deterrents, such as demerits, to reduce bathroom usage. A L.A. based middle school guidance counselor described her experiences while employed at another nearby Charter school, explaining:

. . .My old school has really strict bathroom usage rules; if you had to use the bathroom during class, you’d get a demerit, and we count those up weekly. We expect girls to use the bathrooms during lunch only, but now that I think about it, if you are wearing a pad and it fills up, waiting until lunch would be really difficult. . .so girls might bleed through their pad because of demerits. . .

Numerous girls shared that they felt resigned to wait until after class, often hoping their menstrual products did not leak. Such coping practices, however, left girls feeling distracted and anxious, and thus unable to fully engage or concentrate on learning activities.

Many teachers and school staff explained the rationale behind the complexity of such policies. In particular, they shared that schools must strive to balance girls’ unique bathroom needs with broader safety, disciplinary and health issues for their student populations. While acknowledging that many bathroom policy approaches were flawed, several teachers and school staff shared concerns about students taking advantage of more flexible policies. A school-based social worker in LA articulated his worries, “I think we need to fix the bathroom policy, but it’s tricky, because teachers will think girls will start taking advantage [of it], and boys will want special treatment too.” Such a gendered concern however could be addressed through improved school education around menstruation, thereby reducing menstrual stigma and increasing peer social support.

Discussion

This qualitative and participatory assessment yields important learning on the challenges posed by school bathroom environments and policies on the menstruation experiences of adolescent girls living in U.S.A. cities. Our findings highlight how adolescent girls experience stigma and embarrassment when accessing school bathrooms while menstruating. This often leads to coping strategies, including covertly bringing menstrual products into bathrooms or refraining from visiting them altogether, despite the risk for menstrual stains and subsequent teasing by peers. Such findings are consistent with the broader global menstruation evidence base which highlights the prevalence of menstrual stigma experienced by girls and women (; ), including incidents of shame derived from menstrual strains and teasing (; ) and discomfort and embarrassment when being seen accessing bathrooms, especially while menstruating (; ). Minimal research examining the intersection of bathrooms and menstruation, including beyond school settings, is available in the U.S.A.

Our findings indicated the ongoing menstrual stigma that exists, with many adolescent girls feel uncomfortable disclosing their period status and needs while in school, including to school staff. This suggests that in many schools, teachers and school staff may need to be sensitized to the particular needs of menstruating students and play a more active role in reducing young peoples’ experiences of embarrassment and shame. Reluctance of teachers to discuss menstrual topics (; ) coupled with stigmatizing teacher-led dialog on period topics, has been found to perpetuate negative perceptions of menstruation such as the portrayal of periods as shameful and something to be kept private (; ). Such findings highlight the need for educators to be reflective about their own menstrual experiences, especially as part of teacher education models (); a step which may help support broader cultural shifts in schools that can reduce menstrual stigma.

The social environments commonly found within school bathrooms were also found to pose challenges, exacerbating girls’ discomfort when managing their periods. The various types of socializing that occur in American school bathrooms, including vaping and the creation of social media content (e.g., TikTok videos), have been well-documented by the media (; ; ). Along with introducing stricter school policies to limit student toilet access (), which may inadvertently be augmenting challenges that students face around managing monthly menstrual blood flow, many schools are seeking to manage and reduce these activities through piloting new technologies such as “vape detectors” () or digital hall-passes which track students’ bathroom activities (). However, little is known about the impact of such novel strategies on students’ bathroom experiences, including privacy related concerns such technologies may generate. Regardless, the effort by schools to identify more innovative approaches around bathroom usage might mitigate some students’ period-related privacy discomfort, including reducing bathrooms-based vaping and socializing that in turn will create more comfortable spaces for managing menstruation.

These social and privacy tensions experienced by menstruating students when using school bathrooms may be heightened for transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) youth. Research conducted in the U.S.A. and Canada found that LGBTQ youth often consider communal bathrooms one of the most unsafe places at schools (). Adolescents who menstruate and use the male bathroom (or those designed for cisgender males) may also experience more difficulties with period management, as male bathrooms often lack disposal bins inside stalls (; ). This forces such students to use more publicly situated trash bins for disposing of menstrual waste which heightens their risk of being outed in front of classmates (). In response to growing political advocacy to better support TGNC youth in schools, some states have introduced policies that mandate the provision of gender neutral single-use bathrooms (). The availability of single-use bathrooms, if properly equipped with menstrual disposal and product dispenser hardware, may improve some of the period challenges experienced by TGNC students. However, findings from a small study conducted in New York City would suggest gender-neutral bathrooms in schools are often limited in number, thus posing accessibility issues ().

The physical design of school bathrooms, the limitations of aging school facilities, and issues of toilet maintenance, were also found to hinder privacy and perceptions of comfort when menstruating. Using the integrated model of menstrual experience framework, such findings directly highlight the role of physical environment-related resource limitations in schools directly contributing to negative menstrual experiences, including incidences of distress, concerns about “containment,” and shifting menstrual practices (e.g., wearing a menstrual product longer than desired). Such findings are further supported by the global literature, which focuses on the negative impact of school bathroom design on girls’ menstrual experiences, including insufficient privacy (e.g., lack of locks, inadequate doors), lack of cleanliness and insufficient menstrual disposal options (; ; ). Yet little remains known about the status of school bathrooms within the U.S.A., whether they be in well-funded or poorly funded school districts. A small body of literature has highlighted in particular the deteriorating infrastructure conditions of aging schools in the U.S.A more broadly (; ). According to the National Center for Education Statistics, the average public school building was built around 1968 and requires at least one major facility repair (). The poor state of these buildings directly impacts American students, especially those from low-income backgrounds who were the focus of this study. Evidence from the U.S.A. highlights a negative relationship between school facility quality and student achievement (; ). Media reports from several cities provide insight on the poor quality of bathrooms found in many schools including conditions such as uncleanliness, mold, overflowing trash bins and non-flushable or broken toilets (; ; ; ). There is a need for research exploring current school bathroom infrastructure and its implications on the health and well-being of all students, across genders and experiences.

Prior to the passage of numerous state-level menstrual equity policies across the U.S.A. (), NYC introduced the first municipal-level menstrual equity bill of its kind; implemented in NYC Department of Education operated schools in 2016 (). The NYC legislation mandated the actual location for the provision of menstrual products in schools (e.g., directly inside bathrooms). A legislator responsible for the NYC policy explained the rationale for explicitly designating bathrooms for distribution: “A young girl should not have to tell her teacher, to then tell her counselor, to then be sent to the nurse’s office, to then be given a pad to then go back to the bathroom while a boy is already taking his exam in his classroom.” (). Our findings support this argument, as numerous girls in the study indicated frustration at having to miss class time in order to request a menstrual pad from school administrators. The fidelity of the implementation of the NYC and other state level menstrual equity policies has for the most part not been assessed. Moving forward, policymakers and implementers should prioritize bathrooms as the sites of product distribution in schools as part of ensuring the gender equity of school environments.

Lastly, our findings indicated the importance of bathroom policies for menstrual health. Current school policies regulating bathroom use, such as requiring school passes or limiting the number of visits, were described as making period management challenging for many girls. Given the diversity of girls’ menstrual experiences, including those experiencing heavier and more unpredictable menstrual periods (; ; ), such blanket policies are problematic. Restrictive and one-size-fits-all bathroom policies have also been highlighted as an issue by pediatric bladder health researchers, whose studies have demonstrated that the majority of elementary school teachers designate specific windows of the day for student bathroom use, and that students are often discouraged to use the bathroom outside of that allotted time (). Not only do bathroom restrictions make managing menstruation difficult, but it forces children to hold their urine which can have adverse health effects including lower urinary tract dysfunction ().

Many schools across the U.S.A. lack formal policies surrounding student bathroom usage. A survey of school nurses in the U.S.A. across all grade levels (K-12) reported that 64% of schools lacked a written bathroom use policy (). Limiting access to bathrooms is often rationalized as supporting optimal student learning by keeping students in the classroom (). However, strict bathroom policies can result in girls being preoccupied with a fear of menstrual leaking, and thus hinder concentration in the classroom (). Such fears are not unfounded, as incidents of adolescents bleeding through their clothes at school due to strict bathroom policies have been documented (; ). Similar to our findings about the use of deterrents, such as demerits, to minimize bathroom usage by students, the school nurse survey also identified practices of rewarding students with extra academic credit for not using the bathroom during class (). Such approaches do not support broader “menstrual equity” efforts, especially given the differences in sanitation needs across sexes and individuals. There is a need for broader dialog by education actors on the appropriateness of these policies, including how these regulations can be discriminatory toward menstruating students, particularly those experiencing heavy or irregular bleeding and the discomfort associated with some menstrual disorders.

Limitations

There are a few limitations to note. First, these findings focused on low-income adolescent girls living in three cities in the U.S.A. Our findings are therefore unable to capture the breadth of experiences of girls growing up in rural and suburban communities and across different socioeconomic situations. Second, although our research was conducted with Black and Latina girls in the U.S.A., due to the participatory nature of the study design, we were unable to discern specific differences in experiences based on race or ethnicity. More research is needed exploring the unique MHH experiences of U.S.A. girls across different racial and ethnic identities. Third, as the study participants were largely cisgender girls, our findings cannot provide insights on the experiences of TGNC students and the unique, and potentially heightened, menstruation challenges they may face in schools. Further research is needed to explore the distinct experiences of menstruating TGNC students in school bathroom contexts. Lastly, data collection procedures were ongoing during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020. Challenges with conducting the final IDIs with adolescents during the early phase of COVID-19 resulted in a reduced IDI sample recruited from LA and Chicago. On-going analysis however did indicate that saturation had been reached, and thus it was determined that data was sufficient.

Conclusion

School bathrooms, including both the physical and social characteristics of these environments, can negatively influence girls’ experiences managing their menstruation during the school day. Four key recommendations for future research, practice and policy include: One, expanded research of the school bathroom-related experiences of a social and economic range of menstruating students across the U.S.A, including across a diversity of gender identities; Two, increased attention by schools and policymakers to the design and maintenance of school bathrooms, including basic menstruation-supportive elements (menstrual trash bins and product dispensers); Three, district and state level review of bathroom access policies in schools and the use of deterrents, to meet all students’ unique needs are met, such as those experiencing heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding; and four, improved attention to menstrual stigma in schools, which includes equipping teachers, school staff and students with MHH education and thus enabling all students to voice their menstrual needs. Moving beyond menstrual products to include bathrooms in the fight for menstrual equity would ensure a more holistic and effective approach is utilized across the country, one which considers the needs of all menstruating students.

We would like to express our gratitude to the adolescent girls from Chicago, LA and NYC that participated in our research activities and shared their personal menstruation experiences. We would also like to thank the educators and staff from numerous non-profits and schools in all three cities that shared their valuable expertise during interviews in addition to facilitating study recruitment.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The Sid and Helaine Lerner MHM Faculty Support Fund and the Polan Family Foundation.

Margaret L. Schmitt

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1860-2929

References

- ACLU and Period Equity. (2019). The unequal price of periods: Menstrual equity in the united states. https://www.aclu.org/report/unequal-price-periods

- Agnew S. (2012). The discursive construction of menstruation within puberty education. University of Otago.

- Agnew S., Gunn A. C. (2019). Students’ engagement with alternative discursive construction of menstruation. Health Education Journal, 78(6), 670–680. https://doi.org/10.1177/0017896919835862

- Alexander D., Lewis L. (2014). Condition of America’s public school facilities: 2012-13. National Center for Education Statistics, Institute of Education Sciences.

- Allen K. R., Kaestle C. E., Goldberg A. E. (2011). More than just a punctuation mark: How boys and young men learn about menstruation. Journal of Family Issues, 32(2), 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x10371609

- Asmelash L. (2019, ). High schools embrace “vape detectors” in fight against bathroom vaping. CNN.

- Barrington D. J., Robinson H. J., Wilson E., Hennegan J. (2021). Experiences of menstruation in high income countries: A systematic review, qualitative evidence synthesis and comparison to low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One, 16, e0255001. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.02550 .

- Beausang C. C., Razor A. G. (2000). Young western women’s experiences of menarche and menstruation. Health Care for Women International, 21(6), 517–528. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330050130304

- Bellis E. K., Li A. D., Jayasinghe Y. L., Girling J. E., Grover S. R., Peate M., Marino J. L. (2020). Exploring the unmet needs of parents of adolescent girls with heavy menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea: A qualitative study. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology, 33(3), 271–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2019.12.007

- Benshaul-Tolonen A., Aguilar-Gomez S., Heller Batzer N., Cai R., Nyanza E. C. (2020). Period teasing, stigma and knowledge: A survey of adolescent boys and girls in northern Tanzania. PLoS One, 15, e0239914. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239914

- Bevan J. A., Maloney K. W., Hillery C. A., Gill J. C., Montgomery R. R., Scott J. P. (2001). Bleeding disorders: A common cause of menorrhagia in adolescents. The Journal of pediatrics, 138(6), 856–861. https://doi.org/10.1067/mpd.2001.113042

- Borter G., Lavietes M. (2019). From removing doors to checking sleeves, U.S. schools seek to snuff out vaping. Reuters.

- Boschma J., Brownstein R. (2016). The concentration of poverty in American schools. The Atlantic.

- Branham D. (2004). The wise man builds his house upon the rock: The effects of inadequate school building infrastructure on student attendance. Social Science Quarterly, 85(5), 1112–1128.

- Brooks-Gunn J., Ruble D. N. (1983). The experience of menarche from a developmental perspective. In Brooks-Gunn J., Peterson A. C. (Eds.), Girls at puberty (pp. 155–177). Springer.

- Camenga D. R., Hardacker C., Low L., Williams B., Hebert-Beirne J., James A., Nodora J., Burgio K., Brady S. (2019). A multi-site focus group study of U.S. Adolescent and adult females’ experiences accessing toilets in public spaces, workplaces and schools. Abstracts of long oral presentations, IUGA 44th Annual Meeting. International Urogynecology Journal, 30, 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00192-019-04123-4

- Caruso B. A., Clasen T. F., Hadley C., Yount K. M., Haardörfer R., Rout M., Dasmohapatra M., Cooper H. L. (2017). Understanding and defining sanitation insecurity: Women’s gendered experiences of urination, defecation and menstruation in rural Odisha, India. BMJ Global Health, 2(4), e000414. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000414

- Chinyama J., Chipungu J., Rudd C., Mwale M., Verstraete L., Sikamo C., Mutale W., Chilengi R., Sharma A. (2019). Menstrual hygiene management in rural schools of Zambia: A descriptive study of knowledge, experiences and challenges faced by schoolgirls. BMC Public Health, 19(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6360-2

- Christmann S. (2020). Discount diva: Can Covid change the weird norms people accept in public restrooms? The Buffalo News.

- Coast E., Lattof S. R., Strong J. (2019). Puberty and menstruation knowledge among young adolescents in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. International Journal of Public Health, 64(2), 293–304. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-019-01209-0

- Connolly S., Sommer M. (2013). Cambodian girls’ recommendations for facilitating menstrual hygiene management in school. Journal of Water Sanitation and Hygiene for Development, 3(4), 612–622. https://doi.org/10.2166/washdev.2013.168

- Cotropia C. A. (2019). Menstruation management in United States schools and implications on attendance, academic performance, and health. Women’s Reproductive Health, 9, 1–42. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3313413

- Crankshaw T. L., Strauss M., Gumede B. (2020). Menstrual health management and schooling experience amongst female learners in Gauteng, South Africa: A mixed method study. Reproductive Health, 17(1), 48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-0896-1

- Dillard C. (2019). Equity, period. Teaching Tolerance.

- Edds R. (2015). America, why are there huge gaps at the edge of your toilet doors? Buzzfeed.

- Ehrenhalt J. (2018). Trans rights and bathroom access laws: A history explained. Teaching Tolerance. https://www.tolerance.org/magazine/transgender-bathroom-laws-history

- Elledge M. F., Muralidharan A., Parker A., Ravndal K. T., Siddiqui M., Toolaram A. P., Woodward K. P. (2018). Menstrual hygiene management and waste disposal in low and middle income Countries—A review of the literature. Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(11), 2562. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15112562

- Elmaoğulları S., Aycan Z. (2018). Abnormal uterine bleeding in adolescents: Management. Journal of Clinical Research in Pediatric Endocrinology, 10(3), 191–197. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/abnormal-uterine-bleeding-in-adolescents-management/print?source=see_link

- Fahs B. (2020). There will Be Blood: Women’s positive and negative experiences with menstruation. Women’s Reproductive Health, 7(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23293691.2019.1690309

- Feldman B. (2019). TikTok has turned the school bathroom into a studio. The New York Magazine.

- Filardo M., Vincent J. M., Sullivan K. J. (2019). How crumbling school facilities perpetuate inequality. Phi Delta Kappan. https://kappanonline.org/how-crumbling-school-facilities-perpetuate-inequality-filardo-vincent-sullivan/

- Fitzpatrick L. (2018, ). Dirty schools: CPS cheated to pass cleanliness audits, janitors say. Chicago Sun Times. https://chicago.suntimes.com/2018/4/7/18328593/dirty-schools-cps-cheated-to-pass-cleanliness-audits-janitors-say

- Frank S. E. (2020). Queering menstruation: Trans and non-binary identity and body politics. Sociological Inquiry, 90(2), 371–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12355

- Friberg B., Kristin Örnö A., Lindgren A., Lethagen S. (2006). Bleeding disorders among young women: A population-based prevalence study. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 85(2), 200–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340500342912

- Gootman E. (2004). Dirty and broken bathrooms make for long school day. The New York Times.

- Greed C. (2014, –). Taking Women’s Bodily Functions into Account in Urban Planning: sanitation, toilets, menstruation and biological differences [Conference session]. Engerndering Cities Conference.

- Hennegan J., Shannon A. K., Rubli J., Schwab K. J., Melendez-Torres G. J. (2019). Women’s and girls’ experiences of menstruation in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and qualitative metasynthesis. PLoS Medicine, 16, e1002803. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1002803

- Herbert A. C., Ramirez A. M., Lee G., North S. J., Askari M. S., West R. L., Sommer M. (2017). Puberty experiences of Low-Income girls in the United States: A systematic review of qualitative literature from 2000 to 2014. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(4), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.10.008

- Herbert A. (2018). The Growing Girls Project: Experiences of Puberty and Menstruation in a Low-Income Minority U.S. Context. [Doctoral dissertation, John’s Hopkins School of Public Health]. http://jhir.library.jhu.edu/handle/1774.2/59152

- Ibitoye M., Choi C., Tai H., Lee G., Sommer M. (2017). Early menarche: A systematic review of its effect on sexual and reproductive health in low- and middle-income countries. PLoS One, 12(6), e0178884. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178884

- Jackson T. E., Falmagne R. J. (2013). Women wearing white: Discourses of menstruation and the experience of menarche. Feminism & Psychology, 23(3), 379–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353512473812

- Jamieson C., Kelley B. (2022). States Address Period Poverty With Free Menstrual Products in Schools. Education Commission of the States. https://ednote.ecs.org/states-address-period-poverty-with-free-menstrual-products-in-schools/

- Kelly H. (2019). School apps track students from classroom to bathroom, and parents are struggling to keep up. The Washington Post.

- Koff E., Rierdan J., Sheingold K. (1982). Memories of menarche: Age, preparation, and prior knowledge as determinants of initial menstrual experience. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 11(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01537812

- Ko L. N., Chuang K. W., Champeau A., Allen I. E., Copp H. L. (2016). Lower urinary tract dysfunction in elementary school children: Results of a cross-sectional teacher survey. Urology Journal, 195(4 Pt 2), 1232–1238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.juro.2015.09.091

- Lane B., Perez-Brumer A., Parker R., Sprong A., Sommer M. (2022). Improving menstrual equity in the USA: Perspectives from trans and non-binary people assigned female at birth and health care providers. Culture Health & Sexuality, 24, 1408–1422. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2021.1957151

- Lorenz T. (2020). We’re all in the bathroom filming ourselves. The New York Times.

- Madani D. (2018). Girls reportedly bleeding through pants due to charter school bathroom policy. The Huffington Post.

- Malterud K. (2012). Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(8), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812465030

- Mason L., Nyothach E., Alexander K., Odhiambo F. O., Eleveld A., Vulule J., Rheingans R., Laserson K. F., Mohammed A., Phillips-Howard P. A. (2013). ‘We keep it secret so no one should know’ – A qualitative study to explore young schoolgirls attitudes and experiences with menstruation in rural western Kenya. PLoS One, 8(11), e79132. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079132

- McNamara B. (2019, ). Ohio girl scouts fought to put a tampon locker in their school bathroom. Teen Vogue. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/ohio-girl-scouts-fought-to-put-a-tampon-locker-in-their-school-bathroom?utm_source=twitter&utm_medium=social&utm_campaign=onsite-share&utm_brand=teen-vogue&utm_social-type=earned

- McWilliams J. (2018). Most schools don’t have clear restroom policies, and that’s a huge public-health problem. Pacific Standard.

- Mettler K. (2016). ‘They’re as necessary as toilet paper’: New York city council approves free tampon program. The Washington Post.

- Mueller E., Nebel R., Palmer M. H., Joyce C., Close C. E. (2018). School nurses experience of toileting behaviors in American school: A survey of members of the national association of school nurses. Advancing Female Pelvic Medicine and Reconstructive Surgery.

- Mumtaz Z., Sivananthajothy P., Bhatti A., Sommer M. (2019). “How can we leave the traditions of our baab daada” socio-cultural structures and values driving menstrual hygiene management challenges in schools in Pakistan. Journal of Adolescence, 76, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.07.008 76(July.

- National Equity Atlas. (2017). School poverty. Author.

- Palus S. (2019). Why Can’t we have decent toilet stalls? Slate.

- Phillips-Howard P. A., Caruso B., Torondel B., Zulaika G., Sahin M., Sommer M. (2016). Menstrual hygiene management among adolescent schoolgirls in low- and middle-income countries: Research priorities. Global Health Action, 9(1), 33032. https://doi.org/10.3402/gha.v9.33032

- Porta C. M., Gower A. L., Mehus C. J., Yu X., Saewyc E. M., Eisenberg M. E. (2017). “Kicked out”: LGBTQ youths’ bathroom experiences and preferences. Journal of Adolescence, 56, 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.02.005

- Rheinländer T., Gyapong M., Akpakli D. E., Konradsen F. (2019). Secrets, shame and discipline: School girls’ experiences of sanitation and menstrual hygiene management in a peri-urban community in Ghana. Health Care for Women International, 40(1), 13–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2018.1444041

- Rubinsky V., Gunning J. N., Cooke-Jackson A. (2020). “I thought I was dying:” (Un)Supportive communication surrounding early menstruation experiences. Health Communication, 35(2), 242–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1548337

- Ruble D. N., Brooks-Gunn J. (1982). The experience of Menarche. Child Development, 53(6), 1557–1566. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130084

- Sahoo K. C., Hulland K. R., Caruso B. A., Swain R., Freeman M. C., Panigrahi P., Dreibelbis R. (2015). Sanitation-related psychosocial stress: A grounded theory study of women across the life-course in Odisha, India. Social Science & Medicine, 139, 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.06.031

- Sanchez C. (2018). Brooklyn girl scouts find city isn’t fully implementing menstrual equity law. Gotham Gazette.

- Schmitt M., Booth K., Sommer M. (2022). A Policy for Addressing Menstrual Equity in Schools: A Case Study From New York City, U.S.A. Frontiers in Reproductive Health, 3, 725805. https://doi.org/10.3389/frph.2021.725805

- Sebert Kuhlmann A., Key R., Billingsley C., Shato T., Scroggins S., Teni M. T. (2020). Students’ menstrual hygiene needs and school attendance in an urban St. Louis, Missouri, District. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 444–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.05.040

- Society for Women’s Health Research. (2018). Survey of school nurses reveals lack of bathroom policies and bladder health education. Author. https://swhr.org/survey-of-school-nurses-reveals-lack-of-bathroom-policies-and-bladder-health-education/

- Sommer M., Hirsch J. S., Nathanson C., Parker R. G. (2015). Comfortably, safely, and without shame: Defining menstrual hygiene management as a public health issue. American Journal of Public Health, 105(7), 1302–1311. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302525

- Sommer M., Schmitt M., Gruer C., Herbert A., Phillips-Howard P. (2019). Neglect of menarche and menstruation in the USA. Lancet, 393(10188), 2302. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30300-9

- Sommer M. (2013). Structural factors influencing menstruating school girls’ health and well-being in Tanzania. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2012.693280

- Sommer M., Skolnik A., Ramirez A., Lee J., Rasoazanany H., Ibitoye M. (2020). Early adolescence in Madagascar: Girls’ transitions through puberty in and out of School. The Journal of Early Adolecence, 40(3), https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431619847529

- Sommer M., Ackatia-Armah N., Connolly S., Smiles D. (2015). A comparison of the menstruation and education experiences of girls in Tanzania, Ghana, Cambodia and Ethiopia. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45(4), 589–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.871399

- Strauss V. (2019). Too many of America’s public schools are crumbling — literally. Here’s one plan to fix them. The Washington Post.

- The Mayor’s Office for Economic Opportunity. (2018). NYC opportunity 2018 poverty report. https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/opportunity/pdf/NYCPov-Brochure-2018-Digital.pdf

- Toness B. V. (2019). Boston’s school bathrooms are a big mess. The Boston Globe.

- Uline C., Tschannen-Moran M. (2008). The walls speak: The interplay of quality facilities, school climate, and student achievement. Journal of Educational Administration, 46(1), 55–73. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578230810849817

- U.S. Census. (2016). The 15 most populous cities. US Census Newsroom.

- U.S. Census. (2019a). QuickFacts: Chicago. QuickFacts.

- U.S. Census. (2019b). QuickFacts: Los Angeles. QuickFacts.

- Uskul A. K. (2004). Women’s menarche stories from a multicultural sample. Social Science & Medicine, 59(4), 667–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.11.031

- Wall L. L. (2020). Period poverty in public schools: A neglected issue in adolescent health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(3), 315–316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.027

- Weiss-Wolf J. (2021). The fight for menstrual equity continues in 2021. Marie Claire.

- Wong A. (2019). When schools tell kids they Can’t use the bathroom. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/education/archive/2019/02/the-tyranny-of-school-bathrooms/583660/

- Zia A., Rajpurkar M. (2016). Challenges of diagnosing and managing the adolescent with heavy menstrual bleeding. Thrombosis Research, 143, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2016.05.001