Introduction

In recent years, the integration of digital media into our daily lives has extended to children as well. Particularly during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, there has been a rapid surge in the use of media devices and Internet access. This increased exposure highlights the substantial impact of media on the psychosocial development of children. In contemporary society, the proliferation of digital technologies has precipitated an unprecedented surge in the accessibility and dissemination of information, including sexually explicit content. This phenomenon has significantly impacted the developmental landscape for children leading to premature exposure of minors to sexualized stimuli. The omnipresence of the Internet, coupled with the pervasive influence of social media platforms and diverse media formats, has created a cultural milieu wherein children are increasingly confronted with sexual content, conversations, and vernacular at earlier stages of their cognitive and socioemotional development.

Sexually explicit content can be words, messages, pictures, audio material, or videos depicted in a manner to arouse or titillate. It may vary in its degree of graphicness or explicitness, ranging from mild-to-extremely graphic representations, and it is often subject to cultural, legal, and ethical considerations regarding its production, distribution, and consumption. The “Triple A Engine” posits that three key factors contribute to the Internet’s potency as a tool for sexual content dissemination: accessibility, affordability, and anonymity. Consequently, sexual content becomes readily accessible to any individual with Internet connectivity, often available at no cost and devoid of the necessity to disclose personal information for access. Prior studies have established that a significant portion of adolescent Internet users encounter pornographic material, with the majority exposed before reaching the age of 18. With the widespread availability of the Internet, social media platforms, and various forms of media, children are increasingly encountering sexualized content at younger ages and this exposure is commencing at progressively earlier stages of development. This early exposure can significantly influence their understanding of relationships, body image, and social norms.

Social learning theory, as proposed by Albert Bandura, posits that individuals acquire new behaviors, attitudes, and beliefs through observation, imitation, and modeling of others within their social environment. In the context of childhood exposure to sexual content, children learn about sexuality and sexual behaviors by observing media portrayals, interactions with peers, and familial influences. Through exposure to sexual content in media or discussions with peers, children may internalize attitudes and beliefs about sexuality, which can influence their own behaviors and perceptions. Therefore, it is crucial to understand the social milieu in which the exposure to sexual content occurs as contextual variables, such as parental oversight of media consumption and peer-mediated exposure, could shape both the choice of sexual media content and adolescents’ cognitive processing and behavioral responses to such content. Through this review, we will explore the sociocultural factors contributing to the premature exposure of children to sexual content, its impact on the developmental trajectory, and implications for intervention.

Sociocultural Contributors to Children’s Premature Digital Sexual Content Exposure

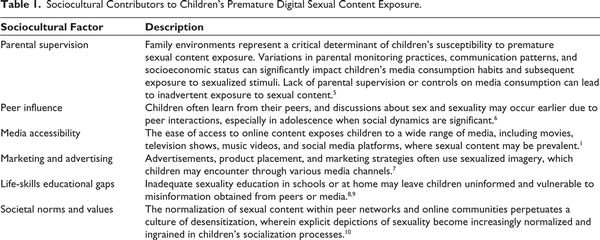

The dynamic interplays between technological advancements, sociocultural norms, familial dynamics, and individual vulnerabilities are central to this inquiry. Technological innovations have democratized access to a vast array of media content, transcending geographical boundaries, and temporal constraints. Table 1 lists and describes some factors contributing to the phenomenon of premature sexual content exposure.

The convergence of social dynamics, media accessibility, and educational curriculum gaps contributes to the premature exposure of children to sexual content. Parental supervision, peer influence, media marketing, societal normalization, and inadequacies in life-skills education collectively shape the environment in which children encounter sexualized stimuli at increasingly younger ages.

Impact of Premature Digital Sexual Content Exposure on the Developmental Trajectory

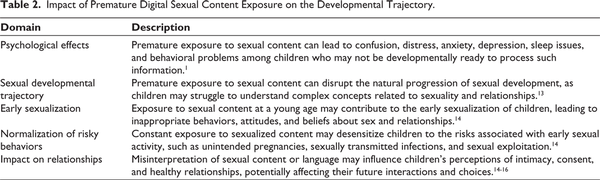

A life-course perspective is central to developmental psychopathology that can be used to evaluate the potential impact of premature exposure of children to sexual content on their developmental trajectories. This perspective emphasizes the significance of early experiences in shaping long-term emotional and cognitive outcomes. The ramifications of premature exposure to sexual content on children’s developmental trajectories are profound and multifaceted. Empirical evidence suggests that early encounters with sexualized media content are associated with an array of adverse psychological sequelae, including heightened levels of anxiety, depression, and body dissatisfaction., Moreover, premature exposure to sexual content may precipitate accelerated cognitive maturation, wherein children are prematurely venture into sociosexual paradigms without the requisite emotional or cognitive capacities to navigate such complexities effectively. Table 2 elucidates some effects of the phenomenon on the development of children and adolescents across various domains with a focus on sexual development.

Amidst the rapid expansion of digital platforms and the pervasive nature of media accessibility, heightened apprehensions have arisen regarding the cascading effects of premature exposure to sexual content on children’s developmental pathways. The early exposure of children to sexual content not only poses risks of fostering developmentally inappropriate and potentially harmful sexual behaviors, but also detrimentally impacts their psychosocial development.

Implications of Premature Digital Sexual Content Exposure for Interventions

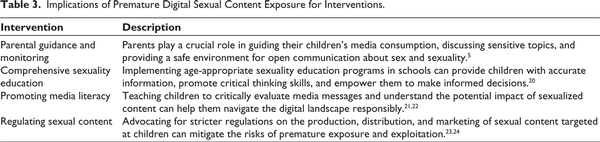

While some sexual behaviors and explorations during childhood are considered normal and aligned with developmental stages, they warrant clinical attention when characterized by aggression, coercion, disparate age or developmental stages between children involved, resistance to adult/caregiver intervention, or causing harm or distress., Moreover, there is a need for proactive interventions to mitigate the potential psychological and social repercussions, safeguarding children’s well-being and promoting healthy developmental outcomes. Table 3 illustrates some of the systemic interventions at family, school, and societal levels that can effectively address the negative impact of this phenomenon and help in fostering a supportive environment conducive to healthy childhood development.

Parental mediation behaviors may encompass establishing guidelines regarding the amount, timing, and type of media content adolescents engage with (restrictive mediation), engaging in conversations about media content with children (active or instructive mediation), and engaging in joint media usage, such as co-viewing television programs. Parental restrictions can decrease children’s exposure to specific types of media content, potentially diminishing their attention to and emphasis on violent and sexual television content. Additionally, restrictions may mitigate sensation-seeking behaviors. The implementation of universal prevention and promotive efforts, encompassing comprehensive sexuality education, media literacy programs, and robust policy and regulation frameworks, is imperative in addressing the complex challenges associated with this early sexual content exposure, fostering informed decision-making and promoting healthy sociosexual development.

Conclusion

Premature exposure to sexual content, talk, and language poses significant challenges to children’s development and well-being. Lack of parental supervision, normalization of sexual content within peer networks and online communities, inappropriate marketing strategies, and inadequate life skills not only have an adverse psychological impact on children but also contribute to deviant sexual developmental trajectories and interpersonal relationship problems. Proactive interventions such as comprehensive sexuality education, enhancing media literacy, parental guidance, and regulating sexual content can safeguard children’s rights, promote healthy sexual development, and foster a supportive environment conducive to their overall well-being. To effectively implement these interventions, a multidisciplinary approach involving educators, policymakers, healthcare professionals, and technology developers is essential. However, addressing this complex issue also requires stronger evidence; this review has methodological limitations, highlighting the need for future systematic reviews.

Authors’ Contribution LS conceptualized and prepared the first draft.

Authors’ Contribution AJPV, RKM, and JVSK critically reviewed the manuscript.

Authors’ Contribution All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Bozzola E, Spina G, Agostiniani R, . The use of social media in children and adolescents: scoping review on the potential risks. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(16):9960. doi:10.3390/ijerph19169960. PMID: 36011593; PMCID: PMC9407706.

- 2. Cooper A. Sexuality and the internet: surfing into the new millennium. Cyberpsychol Behav. 1998;1:187–193. doi:10.1089/cpb.1998.1.187.

- 3. Sabina C, Wolak J, Finkelhor D. The nature and dynamics of internet pornography exposure for youth. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11:169–171. doi:10.1089/cpb.2007.0179.

- 4. Bandura A, McClelland DC. Social Learning Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1977.

- 5. Parkes A, Wight D, Hunt K, Henderson M, Sargent J. Are sexual media exposure, parental restrictions on media use and co-viewing TV and DVDs with parents and friends associated with teenagers’ early sexual behaviour? J Adolesc. 2013;36(6):1121–1133. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.08.019. Epub 2013 . PMID: 24215959; PMCID: PMC3847268.

- 6. Clark DA, Durbin CE, Heitzeg MM, Iacono WG, McGue M, Hicks BM. Adolescent sexual development and peer groups: reciprocal associations and shared genetic and environmental influences. Arch Sex Behav. 2021;50(1):141–160. doi:10.1007/s10508-020-01697-9. Epub 2020 . PMID: 32314108; PMCID: PMC8110336.

- 7. Hu F, Wu Q, Li Y, Xu W, Zhao L, Sun Q. Love at first glance but not after deep consideration: the impact of sexually appealing advertising on product preferences. Front Neurosci. 2020;14:465. doi:10.3389/fnins.2020.00465. PMID: 32547359; PMCID: PMC7273180.

- 8. Kumar R, Goyal A, Singh P, Bhardwaj A, Mittal A, Yadav SS. Knowledge attitude and perception of sex education among school going adolescents in Ambala district, Haryana, India: a cross-sectional study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(3):LC01–LC04. doi:10.7860/JCDR/2017/19290.9338. Epub 2017 . PMID: 28511413; PMCID: PMC5427339.

- 9. Leung H, Shek DTL, Leung E, Shek EYW. Development of contextually-relevant sexuality education: lessons from a comprehensive review of adolescent sexuality education across cultures. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(4):621. doi:10.3390/ijerph16040621. PMID: 30791604; PMCID: PMC6406865.

- 10. Reinecke L. The normalization of childhood sexuality in our culture [Internet]. Available from: https://www.leereinecke.com/blog/the-normalization-of-childhood-sexuality-in-our-culture [Accessed ].

- 11. Pollak SD. Developmental psychopathology: recent advances and future challenges. World Psychiatry. 2015;14(3):262–269. doi:10.1002/wps.20237. PMID: 26407771; PMCID: PMC 4592638.

- 12. Vuong AT, Jarman HK, Doley JR, McLean SA. Social media use and body dissatisfaction in adolescents: the moderating role of thin- and muscular-ideal internalisation. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24):13222. doi:10.3390/ijerph182413222. PMID: 34948830; PMCID: PMC8701501.

- 13. Kar SK, Choudhury A, Singh AP. Understanding normal development of adolescent sexuality: a bumpy ride. J Hum Reprod Sci. 2015;8(2):70–74. doi:10.4103/0974-1208.158594. PMID: 26157296; PMCID: PMC4477452.

- 14. Lin WH, Liu CH, Yi CC. Exposure to sexually explicit media in early adolescence is related to risky sexual behavior in emerging adulthood. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0230242. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0230242. PMID: 32275669; PMCID: PMC7147756.

- 15. Brady SS, Saliares E, Kodet AJ, . Communication about sexual consent and refusal: a learning tool and qualitative study of adolescents’ comments on a sexual health website. Am J Sex Educ. 2022;17(1):19–56. doi:10.1080/15546128.2021.1953658. Epub 2021 . PMID: 37206540; PMCID: PMC10195043.

- 16. Moreira I, Fernandes M, Silva A, . Intimate relationships as perceived by adolescents: concepts and meanings. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2256. doi:10.3390/ijerph18052256. PMID: 33668758; PMCID: PMC7956711.

- 17. Silovsky JF, Letourneau EJ, Bonner BL. Introduction to CAN special issue: children with problem sexual behavior. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;105:104508. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104508. PMID: 32553534.

- 18. Swisher LM, Silovsky JF, Stuart RH, . Children with sexual behavior problems. Juv Fam Court J. 2008;59(4):49–69.

- 19. Smith TJ, Lindsey RA, Bohora S, Silovsky JF. Predictors of intrusive sexual behaviors in preschool-aged children. J Sex Res. 2019;56(2):229–238. doi:10.1080/00224499.2018.1447639.

- 20. Datta SS, Majumder N. Sex education in school. J Clin Diagn Res. 2012;6(7):1362–1364.

- 21. Scull TM, Malik CV, Kupersmidt JB. Understanding the unique role of media message processing in predicting adolescent sexual behavior intentions in the United States. J Child Media. 2018;12(3):258–274. doi:10.1080/17482798.2017.1403937. Epub 2017 . PMID: 30034508; PMCID: PMC6051720.

- 22. Scull TM, Dodson CV, Geller JG, Reeder LC, Stump KN. A media literacy education approach to high school sexual health education: immediate effects of media aware on adolescents’ media, sexual health, and communication outcomes. J Youth Adolesc. 2022;51(4):708–723. doi:10.1007/s10964-021-01567-0. Epub 2022 . PMID: 35113295; PMCID: PMC88 11737.

- 23. Salam RA, Faqqah A, Sajjad N, . Improving adolescent sexual and reproductive health: a systematic review of potential interventions. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(4S):S11–S28. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.05.022. PMID: 27664592; PMCID: PMC 5026684.

- 24. Cant RL, Harries M, Chamarette C. Using a public health approach to prevent child sexual abuse by targeting those at risk of harming children. Int J Child Malt. 2022;5:573–592. doi:10.1007/s42448-022-00128-7.

- 25. Valkenburg PM, Krcmar M, Peeters AL, Marseille NM. Developing a scale to assess three styles of television mediation: “Instructive mediation,” “restrictive mediation,” and “social coviewing”. J Broadcast Electron Media. 1999;43(1):52.

- 26. Nathanson AI. Identifying and explaining the relationship between parental mediation and children’s aggression. Commun Res. 1999;26(2):124–143.

- 27. de Leeuw RN, Sargent JD, Stoolmiller M, Scholte RH, Engels RC, Tanski SE. Association of smoking onset with R-rated movie restrictions and adolescent sensation seeking. Pediatrics. 2011;127(1):e96–e105. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-3443. Epub 2010 . PMID: 21135004; PMCID: PMC3375469.