Introduction

Workplace violence (WPV), defined by both physical and emotional aggression, is a pervasive issue across various occupational settings. However, healthcare workers face unique challenges in relation to WPV given that healthcare settings account for 25% of all reported incidents of violence at work (), with up to 62% of health workers having experienced such abuse (). Among these health workers, nurses are particularly vulnerable due to their direct and frontline roles in patient care. As the largest group within the healthcare workforce () and due to the nature of their client facing work, nurses are overrepresented in WPV statistics. Thus, this paper presents a rapid review of current literature on nurses’ strategies to prevent and report WPV, offering practical insights into reducing this pervasive issue.

The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the problem, with one study revealing that even highly educated individuals and ‘those most trusting of science’ justified violence against healthcare workers (: 315). Nurses’ vulnerability is exacerbated by the nature of their duties, which often involve managing patients in high stress, emotionally charged situations. WPV incidents are more prevalent in certain areas of healthcare, such as emergency departments, mental health, and aged care facilities – settings where nurses are disproportionately represented (). The consequences of this violence are severe: WPV not only leads to burnout, feelings of powerlessness, depression, anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder among nurses () but also contributes to job dissatisfaction, decreased retention rates and reduced quality of care for patients, as nurses under stress tend to exhibit lower levels of empathy and engagement ().

This rapid evidence assessment fills a critical gap in the literature by exploring two thematic areas central to address WPV in healthcare settings, with a specific focus on nurses: prevention and reporting. While there is considerable literature on WPV in healthcare, there remains an urgent need to synthesise the latest research focused on nurses, whose work puts them at higher risk of violence. By identifying effective prevention measures and reporting protocols relevant to WPV against nurses, this review offers insights into how to protect and improve nurses’ well-being and workplace safety. Each of these themes will be discussed in relation to the key findings identified in the reviewed literature, with a particular focus on nurses, whose vital yet vulnerable role in healthcare demands targeted interventions.

Methodology

The aim of this paper is to examine prevention and reporting for nurses experiencing WPV. To do so, the study utilised a rapid evidence assessment methodology, closely associated with the methods outlined by and . We found the rapid review methodology appropriate as they require scientific rigour like systematic reviews but are useful ‘in situations characterised by limited time or resources’ (: 743). Rapid reviews have emerged as ‘as a pragmatic means of informing . . . nursing and midwifery policy, practice and education’ (: 743; see also ). This review was set to be a quick synthesis of existing evidence to be conducted to aid decision-makers in making timely and informed judgements, and to inform the future direction of a wider research project. In brief, we undertook a five-step approach whereby authors (1) discussed the parameters, (2) developed a research protocol and question, (3) conducted a literature search, (4) screened and excluded papers and (5) synthesised knowledge.

To generate the initial list of studies, the following keywords were used Nurs* AND (violence OR ‘workplace violence’, OR aggression OR ‘workplace aggression’ OR ‘occupational violence’ [OR sexual harass*]) AND saf* AND perception on ProQuest Central, EBSCO and Web of Science. These databases were selected because they provide comprehensive coverage of peer-reviewed research in nursing and health sciences. Google Scholar was not used due to concerns about its inclusion of non-peer-reviewed content and the lack of advanced search functionalities compared to the chosen databases, which allow for more precise filtering and retrieval of peer-reviewed literature. Studies that were in a language other than English, that were dissertations or which were created more than 5 years ago were not included in the review. Literature published within 5 years (2017–2022) of the review being undertaken, and that were categorised as prevention and reporting, are included in this rapid evidence assessment. A 5-year timeframe was chosen as it aligns with the rapid evidence assessment’s goal of providing timely, up-to-date insights into prevention and reporting strategies. Given that policies, practices and the understanding of WPV are continually evolving, focusing on recent literature ensures that findings and recommendations are applicable to current workplace settings. The 5-year period also captures relevant literature on the rising trend of WPV against nurses, which has been further exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic ().

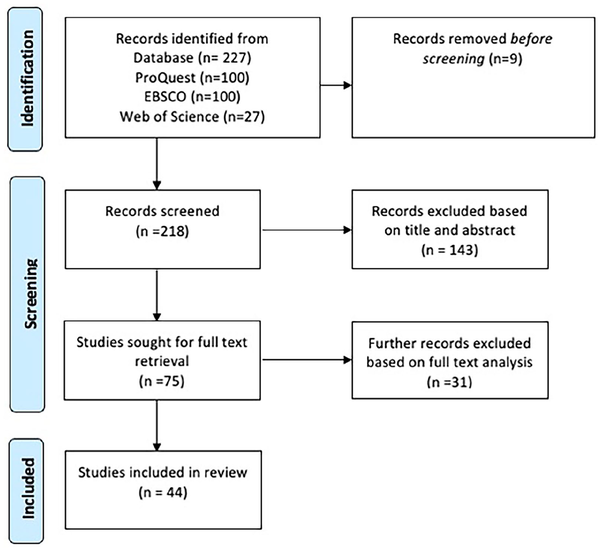

Authors JRM, JR and KL screened all papers based on their abstracts to determine eligibility for inclusion in the review. Papers were included if they (1) directly addressed WPV as a primary focus, (2) specifically focused on nurses, recognising the fact that they bear the brunt of WPV and (3) were peer-reviewed research publications. Papers were excluded if they (1) did not focus on WPV or nursing, (2) were non-peer-reviewed (e.g. reports) or (3) did not meet the quality standards for empirical research as outlined by . Following this initial screening, Author JU conducted a detailed review of the full text of each included paper. Figure 1 illustrates the retrieval process and classification stages.

Figure 1

Retrieval process.

A total of 44 papers were included in the final review, with 16 being reported on in this evidence assessment. Papers classified under prevention and reporting were used in the following rapid evidence assessment while those classified as resources and incidents are reported elsewhere. See Table 1. The below findings will examine prevention and reporting of WPV against nurses.

Integrated findings and discussion

Prevention

Actuarial risk assessments

Although nurses are trained in using clinical judgement to identify patients at risk of violence (), there have been trials of actuarial risk assessments aimed at objectively assessing individuals’ current risk of engaging in aggression or violence. A study conducted by evaluated the implementation of the Broset Violence Checklist (BVC) as a routine screening tool in a metropolitan hospital emergency department in Australia. The BVC is a six-item instrument that predicts an individual’s risk of violence within the next 24 hours based on the presence of specific patient characteristics or behaviours. The BVC provides a set of recommended interventions corresponding to patient risk level. All staff working in the ED were invited to participate in two separate surveys: one conducted before the implementation of the BVC and another conducted approximately 2 years later. After the implementation of the BVC, nurses reported a significant increase in confidence and performance in conducting risk screening; however, they did not perceive any change in their ability to prevent violence. Notably, the utilisation of the BVC resulted in a substantial increase in the documentation of violence risk assessments, rising from 30% to 82%. Out of the assessed patients, 1% were classified as high risk, 4% as moderate risk, whereas the majority were deemed to have a low risk of violence within the next 24 hours.

Furthermore, the implementation of the BVC seemed to reduce unplanned code greys, which are unexpected assaults on staff during patient transport. At the same time, there was an increase in planned code greys, where organised teams comprising security and clinical staff worked together to safely move a patient. These findings suggest the adoption of the BVC by nursing and security staff improved the identification and management of individuals at risk of violence. As a result, staff utilising the BVC are better equipped to collaborate and effectively manage patient risk.

Other research highlights the crucial role of a cooperative relationship between security and clinical staff in improving perceptions of safety in the ED and reducing and/or preventing the risk of patient violence (). The presence of visible security staff on the ward and their prompt response to episodes of aggression and violence significantly increased the likelihood of clinical staff feeling safe, with a 2.1-fold increase for ‘visibility’ and a 3.5-fold increase for ‘quick response’.

Leadership

Furthermore, there are factors at an organisational level that can alter the likelihood of violence occurring. Research has shown that the extent to which leadership teams prioritise occupational health and safety (OHS) of employees is a crucial factor in preventing violence (). Utilising logistic regression analysis, the researchers found that workplaces focusing on OHS leading indicators (OR = 0.69), prioritising employee safety (OR = 0.52) and having supervisors who support the need for safety (OR = 0.89) were significantly associated with a lower likelihood of violence. These findings imply that the prevention and/or reduction of violence is not solely attributed to individual actions but are also driven by the sociocultural context of the organisation. Specifically, organisations possess the capability to allocate resources towards reducing WPV. This investment might improve protective measures like modifying physical boundaries or environments (e.g. installing high counters, duress alarms, etc.) in high-risk areas.

Violence management programmes

Despite nurses’ attitudes and skills being an important factor in the prevalence of WPV, recent research has demonstrated that skills training in violence management is uncommon outside of a psychiatric setting. Indeed, evaluated the impact of a violence training programme on nurses’ confidence (N = 38) to respond to patient aggression. Although the findings supported violence training as improving nurses’ confidence in responding to aggression, the most striking finding was that 82.61% of the sample reported never having received prior training in aggression management. Evidently, few nurses in this sample believed they were equipped to manage instances of aggression or violence, and this could place them at greater risk of WPV.

Based on the surveyed literature, the frequency of violence management programmes might not adequately accommodate the onboarding of new staff members. A study conducted by revealed that among the nursing sample surveyed, 75% of participants reported experiencing WPV, yet two-thirds of them indicated that they had never received any prior training specifically addressing the management of WPV. Moreover, the study found that more than half of the nurses expressed uncertainty regarding their ability to manage WPV, whereas an additional quarter stated feeling ‘incapable’ of effectively handling WPV situations. These findings emphasise two key points: first, a significant number of nurses have not undergone training specifically addressing the management of WPV, and second, a substantial proportion of nurses lack confidence in their ability to effectively handle WPV incidents.

Indeed, organising regular and frequent violence management training sessions can be deemed costly, time-consuming and generally challenging, especially in environments that are under-resourced and subject to time constraints. Despite the challenges associated with hosting regular training sessions, the potential benefits in terms of preventing and/or reducing incidents of violence can outweigh these difficulties. The issue of inadequate training for WPV extends beyond healthcare settings. Even in educational nursing programmes, student nurses have expressed feeling ill-prepared to handle instances of patient violence (), indicating that the skills required to manage WPV are not sufficiently taught at a university level nor in a workplace setting. These gaps in education at various institutional levels represents a substantial barrier in skill development for nurses, and one that poses a challenge to the management of WPV.

Limitations of time

Another significant barrier to preventing WPV is the prevailing condition of nurses being consistently overworked and under-resourced. As a result, nurses often face a shortage of available time to fulfil all the required job tasks, including the implementation of preventative measure for WPV. The demanding working conditions experienced by nurses can make it challenging to adhere to routine tasks such as conducting violence risk assessments. Despite the introduction of the BVC which resulted in a notable increase in risk assessments from 30% to 82% (), approximately one in five assessments remained incomplete. The number of incomplete risk assessments suggest that factors such as time-constraints continue to impact the completion rates of risk assessment.

The lack of time is likely compounded by the high demand for services, which leads to long waiting lists, especially in areas like the ED. These delays can be exacerbated by patients with high needs, such as alcohol-related cases () and methamphetamine users (). Substance users may require the attention of multiple staff members, particularly in cases of anticipated violence. As a result, ward acuity can be negatively affected causing certain tasks like violence risks assessments to be deprioritised. Although risk assessments are crucial for identifying individuals at risk of violence, they may not be completed due to competing priorities. Neglecting violence risk assessments can contribute to the escalation of violence in two ways. First, the absence of risk assessment makes it hard to implement intervention as it is unclear who is likely to become violent. Second, people at risk of violence may benefit from treatment prioritisation to reduce their waiting time as one mechanism to limit agitation and distress: known contributors to violence. In a study conducted by , security personnel shared their perspectives on the causes of patient aggression. One finding highlighted that extended waiting times often triggered patient aggression, suggesting these delays serve as a barrier that heightens the risk of WPV.

Clinical and security staff

Third, effective teamwork, communication and integration between clinical and security staff hold the potential to prevent numerous episodes of WPV. Although research () highlights the presence of security personnel as one mechanism to enhance perceptions of safety on the ward and can aid in mitigating or preventing WPV, some research indicates discontent between different teams. For instance, in a study conducted by , 26 security staff were interviewed to gain insights into their experiences while intervening with problem patient behaviours at the request of clinical staff. The security staff who participated in the study voiced multiple concerns which included feeling undervalued, excluded from the team and subject to disrespectful treatment. Additionally, participants expressed feeling that their safety was not prioritised the same as clinical staff. Furthermore, it was observed that despite experiencing both physical and psychological harm, security staff were not involved in team debriefings that followed incidents of violence.

Several members of the security team emphasised their extensive experience in managing problem behaviour and their proficiency in verbal de-escalation, thus underscoring their potential as a valuable resource in preventing WPV. Medical staff (of which nurses are included) may have a limited understanding about the utility of security personnel. Nurses tended to perceive security staff as occupying a lower position in the occupational hierarchy, often overlooking the integral role that security staff plays in ensuring patient care and safety. The lack of integration between nursing and security teams poses a significant barrier to efficient management of problem behaviour, making it more challenging to prevent and reduce instances of violence. Clearly, there would be potential benefits for both clinical and security staff if they were to collaborate more closely in the management of problem patient behaviour.

Safewards model

Additionally, organisations may implement different clinical models and interventions aimed at enhancing patient care and safety. One such example is called the Safewards Clinical Model which is an initiative aimed at reducing episodes of violence, minimising the use of restraint and containment and enhancing patient care in inpatient psychiatric units. In their review of the implementation of the Safewards model in three inpatient psychiatric wards in Queensland, identified that the successful implementation of the model was influenced by senior nursing leaders and management. The study findings underscore the importance of senior leaders as being responsible for driving the necessary changes at an organisational level as one mechanism to reduce WPV.

The extent of leadership support for change initiatives, such as the implementation of new clinical models, can serve as another barrier that may impact the success of violence prevention efforts. The Safewards model analysed by highlights the importance of senior leadership in the implementation process. Several participants (i.e. registered nurses) highlighted the substantial responsibility and influential role that senior nursing managers hold in shaping and guiding nursing practices within the ward. However, there were instances where the new model was implemented poorly (or not at all), specifically when senior nursing managers lacked investment in the change, delegated the implementation to other staff or failed to provide adequate support in staff training. Furthermore, nurses reported feeling a lack of power to implement interventions due to their lack of seniority, hence showing the need for senior nurses to be involved in the programme’s implementation. However, it is outlined that senior nursing managers were often busy and were not always interested in implementing new models. As such, despite the potential for the Safewards model to improve nursing practice and reduce instances of WPV, it seems that its implementation is largely dependent upon nursing leaders to implement it.

Reporting

Organisational culture and support

Most nurses identified enablers to reporting were located at the organisational level (), justified by the type of organisational culture and support processes in place. When nursing supervisors and managers created a culture supportive of reporting incidents, nursing staff were more likely to report a WPV incident. Nurses identified several organisational factors that influenced their intentions to report, including the availability of tap out programmes (allowing nurses to swap patients when faced with challenging behaviour), the existence of patient behaviour management plans, mechanisms to document problem patient behaviour such as violence and the practice of sending accountability letters to patients after violent incidents. Only a limited number of papers identified factors that nurses perceived as relevant in influencing their reporting of WPV incidents.

Nurse dedication to patient care

Many of the reviewed papers identified individual barriers that prevented them from reporting incidents of WPV. Firstly, many nurses reported having a high tolerance for WPV (), with some nurses going so far as to feel ‘proud’ that their hospital does not ‘ban’ patients (). The dedication of nurses to patient care has normalised frequent incidents of WPV, often resulting in underreporting, particularly for incidents perceived to be insignificant or minor. In a study by , over 50% of nurses indicated that they would not take any action following an episode of WPV, implying that many nurses choose to let aggressive behaviour persist rather than reporting it. Given that minor injuries are relatively common when restraining physically aggressive patients, staff reported rarely documenting these injuries ().

In a study conducted by , some nurses also expressed a reluctance to report patients with complex behavioural and mental issues. This reluctance to report was further intensified when the nurses had previously encountered unsatisfactory responses to their reports. Conversely, some nurses attribute their decision to report incidents of aggression and violence to positive experiences with the police, highlighting the importance of a positive response as affecting future intentions to report WPV incidents. Additionally, nurses in the study conducted by described challenges in reporting incidents of WPV perpetuated by patient advocates, such as family members or friends, due to the limited availability of information about these individuals. There was also a common consensus amongst many nurses that reporting WPV would be an ineffective solution ().

Administrative procedures

The issues associated with a lack of reporting can be attributed to organisational-level issues that hinder nurses’ capacity to file incident reports. Often, nurses cited administrative procedures that must be followed as a barrier to reporting WPV. While certain organisations employ a ‘RiskMan’ system that enables nurses to document risk-related incidents, nurses in the study conducted by found the process of creating these reports to be challenging and time-consuming. Another group of nurses described incident reporting forms as lengthy and complicated ().

Nurses in the same study further highlighted the absence of follow-up support from their employers, despite expressing a strong desire for such support throughout the incident reporting process. A similar sentiment was echoed by nurses in other studies (; ), where nurses described a dearth of post-reporting communication. Nurses stated that a lack of post-reporting communication implied that their employers did not consider their reports as serious and believed that no action would be taken, suggesting that some nurses may not perceive personal or organisational benefits in reporting incidents of WPV. Some nurses even describe potential consequences if they were to report incidents of WPV, including facing abuse from management or being accused of being responsible for the reported issues (). Furthermore, a study by revealed a widespread dissatisfaction among nurses when reporting incidents of WPV to external organisations. The above administrative obstacles all contribute to the underreporting of WPV.

Implications for future research and practice

This rapid evidence review forms part of a larger body of work where 44 papers were analysed. The papers analysed as prevention and reporting papers were the lowest frequency of reviewed papers (n = 16). In addition to this, only a limited number of papers identified factors that nurses perceived as relevant in influencing their reporting of WPV incidents suggesting it is an under researched area.

This review indicated that there is a lack of incentive for nurses to report WPV, including a lack of time to fill out lengthy forms. To address these issues, it is recommended to streamline the incident reporting process by simplifying the administrative burden and introducing a designated complaints officer to effectively address staff complaints of WPV, thus increasing nurses’ trust in their organisations. Additionally, there is significant room for improvement in educating nurses about WPV. This should begin by incorporating better WPV education into tertiary education programmes and followed by regular training on available resources by organisations. Addressing the challenges of preventing and reporting WPV necessitates a comprehensive approach involving organisational support, training, communication and policy enhancements. Only by addressing these aspects we can foster safer working environments for nurses and enhance the quality of care provided to patients.

Conclusion

There are several interventions available to prevent and/or reduce WPV against nurses. However, in practice, many other factors exist which complicate the likelihood of WPV being prevented and/or reported. While violence training programmes have the potential to educate staff on identifying, assessing and intervening with aggressive and violent patients, their effectiveness in achieving the desired outcomes is not definitively established. Although numerous programmes prioritise the evaluation of acquired knowledge through practical examinations of skills in simulated environments, there remains a notable absence of assessments that measure the application of these skills in real-life scenarios (). Therefore, the extent to which the knowledge is obtained from violence management training programmes is effectively transferred to practical settings remains uncertain.

In addition, nurses identified multiple personal characteristics that reduced or prevented the occurrence of WPV. In fact, among the reviewed papers, the majority primarily focused on barriers to reporting, revealing the numerous obstacles in the reporting process. In contrast, there were few papers that highlighted the enablers of reporting. Staff who were trained in identifying aggressive and violent patients and were skilled at de-escalation were generally more successful in preventing patient behaviour from escalating. Staff may rely on behavioural warning signs to identify patients at risk of becoming violent. These signs may include agitation, pacing or raised voices (). Once identified, staff can implement strategies such as distraction, verbal de-escalation and, if necessary, manual and/or chemical restraint to prevent the escalation of violence ().

Key points for policy, practice and/or research

Nurses discuss various factors that facilitate or impede their efforts to prevent and report incidents of WPV, encompassing personal, organisational and societal factors.

The effective prevention of WPV hinges on organisational backing, which includes the implementation of robust training initiatives and the presence of visible security personnel.

To address obstacles related to the reporting of WPV, such as insufficient managerial training and nurses grappling with burnout, organisational adjustments are imperative.

Enhanced education aimed at reducing WPV in settings beyond high-risk environments, coupled with the promotion of closer collaboration between security personnel and nursing staff, represents a vital approach.

The authors wish to acknowledge the generosity of the nurses and practitioners whose consultation helped to determine the scope and need for this review. The authors also wish to acknowledge the early work of Julie Youssef who assisted in the early stages of this review.

Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical approval Ethical approval was not sought for this review as it did not involve recruiting human subjects.

Joel Robert McGregor

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3336-2190

Xavier MIlls

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9758-7167

References

- Australian Government (2024) National Nursing Workforce Strategy. Department of Health and Aged Care. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/our-work/national-nursing-workforce-strategy (accessed 18 September 2024).

- Casey C (2019) Management of aggressive patients: Results of an educational program for nurses in non-psychiatric settings. Medsurg Nursing 28: 9–21.

- Chapman R, Ogle KR, Martin C, et al (2016) Australian nurses’ perceptions of the use of manual restraint in the Emergency Department: A qualitative perspective. Journal of Clinical Nursing 25: 1273–1281. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.13159.

- Dafny HA, Beccaria G (2020) I do not even tell my partner: Nurses’ perceptions of verbal and physical violence against nurses working in a regional hospital. Journal of Clinical Nursing 29: 3336–3348. DOI: 10.1111/jocn.15362.

- Díaz Crescitelli ME, Ghirotto L, Artioli G, Sarli L (2019) Opening the horizons of clinical reasoning to qualitative research. Acta Biomed for Health Professions 90: 8–16. DOI: 10.23750/abm.v90i11-S.8916.

- Egerton-Warburton D, Gosbell A, Wadsworth A, et al (2016) Perceptions of Australasian emergency department staff of the impact of alcohol-related presentations. Medical Journal of Australia 204: 155. DOI: 10.5694/mja15.00858.

- Higgins N, Meehan T, Dart N, et al (2018) Implementation of the Safewards model in public mental health facilities: A qualitative evaluation of staff perceptions. International Journal of Nursing Studies 88: 114–120. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.08.008.

- Hills D, Lam L, Hills S (2018) Workplace aggression experiences and responses of Victorian nurses, midwives and care personnel. Collegian (Royal College of Nursing, Australia) 25: 575–582. DOI: 10.1016/j.colegn.2018.09.003.

- Johnston S, Fox A (2020) Kirkpatrick’s evaluation of teaching and learning approaches of workplace violence education programs for undergraduate nursing students: A systematic review. The Journal of Nursing Education 59: 439–447. DOI: 10.3928/01484834-20200723-04.

- Jonas-Dwyer DRD, Gallagher O, Saunders R, et al (2017) Confronting reality: A case study of a group of student nurses undertaking a management of aggression training (MOAT) program. Nurse Education in Practice 27: 78–88. DOI: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.08.008.

- Khangura S, Konnyu K, Cushman R, et al (2012) Evidence summaries: The evolution of a rapid review approach. Systematic Reviews 1: 10. DOI: 10.1186/2046-4053-1-10.

- O’Keeffe V, Boyd C, Phillips C, et al (2021) Creating safety in care: Student nurses’ perspectives. Applied Ergonomics 90: 103248. DOI: 10.1016/j.apergo.2020.103248.

- O’Leary DF, Casey M, O’Connor L, et al (2017) Using rapid reviews: An example from a study conducted to inform policy-making. Journal of Advanced Nursing 73: 742–752. DOI: 10.1111/jan.13231.

- Partridge B, Affleck J (2017) Verbal abuse and physical assault in the emergency department: Rates of violence, perceptions of safety, and attitudes towards security. Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal 20: 139–145. DOI: 10.1016/j.aenj.2017.05.001.

- Pich J (2017) Violence in Nursing and Midwifery in NSW: Study Report. NSW Nurses and Midwives’ Association: NSW Nurses and Midwives’ Association. NSW, Australia.

- Pich JV, Kable A, Hazelton M (2017) Antecedents and precipitants of patient-related violence in the emergency department: Results from the Australian VENT Study (Violence in Emergency Nursing and Triage). Australasian Emergency Nursing Journal 20: 107–113. DOI: 10.1016/j.aenj.2017.05.005.

- Senz A, Ilarda E, Klim S, et al (2021) Development, implementation and evaluation of a process to recognise and reduce aggression and violence in an Australian emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia 33: 665–671. DOI: 10.1111/1742-6723.13702.

- Shea T, Sheehan C, Donohue R, et al (2017) Occupational violence and aggression experienced by nursing and caring professionals: Occupational violence and aggression. Journal of Nursing Scholarship 49: 236–243.

- Spelten E, Thomas B, O’Meara P, et al (2020) Violence against emergency department nurses; Can we identify the perpetrators? PLoS One 15: e0230793–e0230793. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0230793.

- Thomas B, McGillion A, Edvardsson K, et al (2021) Barriers, enablers, and opportunities for organisational follow-up of workplace violence from the perspective of emergency department nurses: A qualitative study. BMC Emergency Medicine 21: 19. DOI: 10.1186/s12873-021-00413-7.

- Tiesman HM, Hendricks SA, Wiegand DM, et al (2023) Workplace violence and the mental health of public health workers during COVID-19. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 64: 315–325. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2022.10.004.

- Usher K, Jackson D, Woods C, et al (2017) Safety, risk, and aggression: Health professionals’ experiences of caring for people affected by methamphetamine when presenting for emergency care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 26: 437–444.

- Wand T, Bell N, Stack A, et al (2020) Multi-site study exploring the experiences of security staff responding to mental health, drug health and behavioural challenges in the emergency department. Emergency Medicine Australasia 32: 793–800. DOI: 10.1111/1742-6723.13511.

- World Health Organization (2023) Violence and harassment [Online]. WHO. Available at: https://www.who.int/tools/occupational-hazards-in-health-sector/violence-harassment (accessed 17 May 2023).