Parents’ loneliness in sole and joint physical custody families

Previous research has repeatedly shown that parents’ well-being in post-separation families is worse than parents’ well-being in nuclear families (e.g., ). However, a comparison of parents who have experienced separation or divorce with those who have not is insufficient, because it suppresses potential differences within the group of separated parents (for a request of within-group comparisons see ). According to the divorce-stress-adjustment perspective by , divorce and separation are processes that are accompanied by events that will be perceived as stressful by the affected individuals. However, the extent to which these stressors affect well-being depends on numerous moderating and protective factors, resulting in measurable differences within the group of separated parents. One factor that is hypothesized to affect parents’ post-separation well-being is the physical custody arrangement that the family practices. During the last decades, the most common post-separation care arrangement has been sole physical custody (SPC), an arrangement in which children live with one resident parent (mostly mothers) and see the non-resident parent (mostly fathers) seldom if ever. However, with fathers playing an increasingly active role in their children’s lives (), joint physical custody (JPC) has emerged as a new type of post-separation care arrangement. The most frequently used definition of JPC is that children spend not more than 70% of their time with the resident parent (), with a more fine-grained definition further differentiating between asymmetric JPC (children spend 51%–70% of the time with the resident parent) and symmetric JPC (children spend 50% of the time with each parent) ().

Although there has been considerable research activity on the effects of JPC in the last decades, studies on this topic have concentrated almost exclusively on children’s well-being (), which may be the case because most laws on physical custody arrangements (like those in Germany) stress that the “best interest of the child” should guide decisions on physical custody, ignoring its effects on parents. This is unfortunate, given that well-being is not only important for parents themselves in terms of decision making and life chances, but can also directly and indirectly affect the well-being of their children (e.g., ; ).

One important aspect of well-being is social well-being, which is often measured as loneliness; that is, “an individual’s subjective evaluation of his or her social participation or isolation” (, p. 582). Separation and divorce have been found to be associated with a reduction in social contacts and, thus, lowers levels of social integration (e.g., ). There are, however, reasons to expect differences in terms of loneliness among parents with different types of physical custody arrangements. Resident parents who practice JPC share parenting responsibilities more equally with the other parent and live with their children only “part-time” (, p. 173). Thus, when compared to their counterparts with SPC, resident parents with JPC should have more time they can spend on other life domains, including paid employment (), leisure activities, and social activities (). Resident parents with JPC may also benefit from having higher chances of repartnering than resident parents with SPC (). These advantages should, in turn, result in higher levels of social well-being and fewer feelings of loneliness.

Empirical research on parents’ social well-being in post-separation families is generally scarce and the only study with a main focus on this aspect found that mothers with JPC were more engaged in outdoor home activities and better maintained their social networks than mothers with SPC, whereas the physical custody arrangement did not make a difference for fathers (). Other research on parents’ well-being in different physical custody arrangements has shown that parents with JPC had higher life satisfaction than parents with SPC because they had better parent-child relationships and were more engaged in leisure activities (). Furthermore, the positive effects of JPC for mothers could be attributed to their higher chances of re-partnering compared to mothers with SPC (; ). JPC was also found to be associated with less time pressure for mothers and slightly greater time pressure for fathers compared to their respective counterparts in mother SPC families (). However, other studies did not find differences between parents in SPC and JPC families regarding their satisfaction with their financial situation and family life () and their emotional well-being (). Considering both direct and indirect effects of physical custody arrangements on parents’ subjective well-being, another study found only indirect effects of more parenting time, positive for mothers and negative for fathers ().

The present study sought to investigate differences in social well-being among parents in post-separation families by examining feelings of loneliness in resident parents who practiced either SPC, asymmetric JPC, or symmetric JPC. A more fine-grained differentiation of physical custody arrangements into SPC (one parent is almost alone responsible for childcare), asymmetric JPC (parents share childcare more equally), and symmetric JPC (parents share childcare equally) is an important next step in research on separated families, because it enables us to answer the question of whether an equal division of childcare between the separated parents adds to their well-being.

Method

Data and analytical sample

To investigate the relationship between physical custody arrangements and the social well-being of resident parents, data from the Family Models in Germany (FAMOD) study was used (). The FAMOD study is a convenience sample of 1,554 nuclear, SPC, and JPC families with children below the age of 15. It was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and data were collected in 2019 by Kantar Public. The sample was stratified by a) family model (nuclear, SPC, and JPC) and b) age of a selected target child (0–6 and 7–14 years old). In separated families, the target child had to have contact with both biological parents for the family to be included in the study. Although a convenience sampling strategy was employed, the distributions of several of the respondents’ socioeconomic characteristics (e.g., age and health) were very similar to the distributions in the German population (). All statistical analyses for this study were based on information provided by the parent with whom the target child was registered.

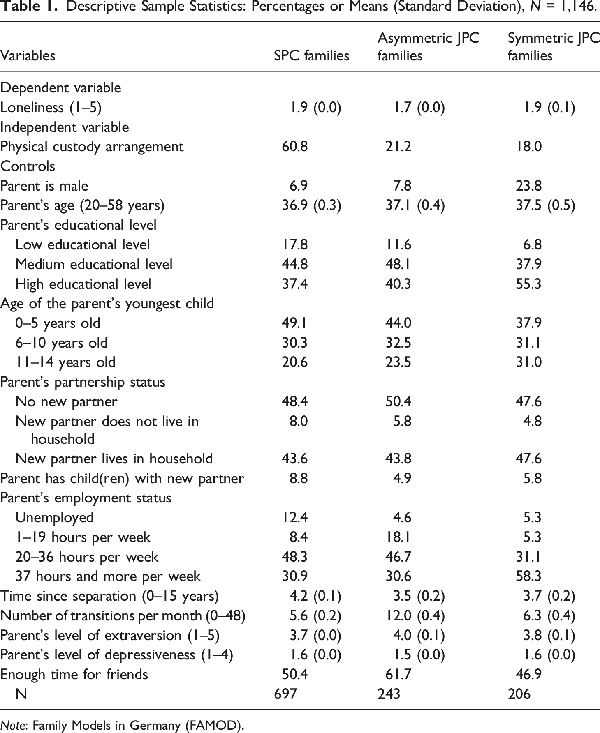

Because the focus of the analysis was on parents in separated or divorced families, in a first step, all nuclear families (n = 321) were deleted from the analytical sample. Second, all respondents were excluded from the analysis if the physical custody arrangement they practiced could not be identified (n = 63). Third, due to low case numbers, all non-resident parents were deleted from the sample (n = 24) There were no missing values on the dependent variable and all missing values on the control variables were imputed by means of multiple imputation (chained equations, 50 imputations), resulting in a final analytical sample of 1,146 resident parents in post-separation families, including 697 parents in SPC families, 243 parents in asymmetric JPC families, and 206 parents in symmetric JPC families.

Variables

Dependent variable

The dependent variable measures the parent’s feelings of loneliness with the question how much they agreed with six items when considering their situation during the last 4 weeks, for example “There are enough people I feel close to” or “I miss having people around.” The response categories for each item were completely agree (1) to completely disagree (5). The responses to these items were combined to a mean scale on which higher values suggest more feelings of loneliness (α = 0.83).

Independent variable

The independent variable is the physical custody arrangement that was assessed using a residential calendar () in which the respondents indicated the days and nights the target child was spending with the mother or the father during 4 weeks of a typical month. If the selected target child was living more than 70% of the time with the respondent over the course of a typical month, the respondent was identified as having SPC (0). If the target child was spending between 51% and 70% of the time with the respondent, the respondent was having asymmetric JPC (1). If the target child was spending 50% of the time with each parent, the respondent was having symmetric JPC (2).

Control variables

The parent’s gender was either female (0) or male (1). Note that the FAMOD questionnaire allowed the respondents to be identified only as female or male. The parent’s age was assessed by using the parent’s year of birth and the year of data collection. Based on information about each respondent’s general school-leaving certificate, the sample was divided into three groups measuring the parent’s educational level: low educational level (0; no school-leaving certificate or the lowest formal qualification of Germany’s tripartite secondary school system), medium educational level (1; intermediary secondary qualification), and high educational level (2; at minimum, a certificate fulfilling the entrance requirements for a university of applied sciences). According to the age of the parent’s youngest child, the sample was split into three groups: 0-5 years old (0), 6-10 years old (1), and 11-14 years old (2). Moreover, the respondents were divided into groups according to their partnership status (no new partner (0), new partner does not live in household (1), and new partner lives in household (2)), child withnewpartner (no child(ren) with new partner (0) vs. child(ren) with new partner (1)), and employment status (unemployed (0), 1-19 hours per week (1) , 10-36 hours per week (2), 37 hours and more per week (3)). The time since the separation from the child’s other parent was calculated using information about the year in which the respondents separated from the target child’s other biological parent and the year of data collection. Based on information from the residential calendar, the number of transitions per month that the target child was making between the parental households was calculated by counting how often the child was moving between the two households during a typical month. The parent’s level of extraversion was measured with two items from a shortened version of the Big Five Inventory: “I am usually modest and reserved” and “I am extroverted.” Each item had five response categories ranging from completely false (1) to completely true (5), and the two items were combined to a mean scale with higher scores indicating higher levels of extraversion (α = 0.60). For an assessment of the parent’s depressiveness, this analysis used the State-Trait-Depression Scales (STDS), which consist of five items that measure negative mood and five items that measure positive mood. The items include statements like: “My mood is melancholy,” “I am depressed,” and “I feel secure.” The response format for each item ranged from almost never (1) to almost always (4). For the purposes of this study, a mean scale was computed, with higher values indicating higher levels of depressiveness (α = 0.84). To assess whether the parent had enough time for friends, the question “How much time do you estimate you currently spend on the following things or persons? Is the time you spend too little, just right, or too much?” was used with respect to the dimension “friends.” For the statistical analysis, the sample was split into two groups: Parents who indicated that they had too little time for friends were identified as having not enough time (0), whereas parents who indicated that they had either just the right amount of time or too much time were identified as having enough time (1). The descriptive sample statistics for all variables are displayed in Table 1.

Results and discussion

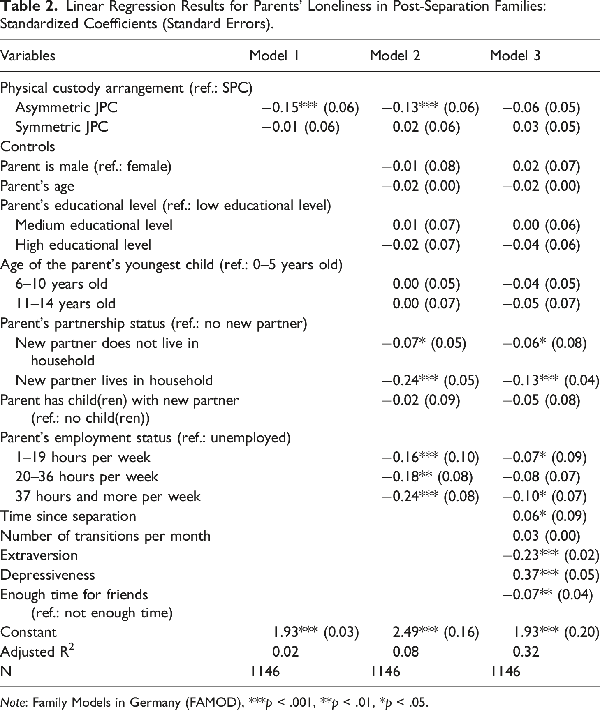

The bivariate results of the linear regression in Table 2 revealed significant differences between parents with SPC and asymmetric JPC: Parents practicing asymmetric JPC indicated that they felt less lonely than parents practicing SPC (Model 1). With the inclusion of socio-demographic variables, the differences between parents with SPC and asymmetric JPC remained significant (Model 2). However, after adding the rest of the control variables to the regression models, the differences between resident parents with SPC and asymmetric JPC disappeared (Model 3). A closer look revealed that the parents’ levels of extraversion and depressiveness and their time for friends were the main drivers of the initially observed association. All of these variables were significantly related to feelings of loneliness, with extraversion and time for friends reducing them and feelings of depression increasing them. Additionally, having a partner (living either within or outside of the household) and being employed each reduced feelings of loneliness. However, more time since the separation from their child’s other biological parent was related to more feelings of loneliness. In contrast, neither bivariate nor multivariate differences could be observed between parents with SPC and symmetric JPC.

Although the research question and, thus, the focus of this short report was on the association between post-separation physical custody arrangements and resident parents’ loneliness, it is worth emphasizing that only Model 3 that included all control variables accounted for a substantial share of variance (32%). As mentioned in the previous paragraph, feelings of loneliness among separated and divorced parents were mainly explained by the parents’ levels of extraversion and depressiveness and the time they had for friends. With these findings we add new insights to the very scarce prior research on the relationship between marital status and loneliness or social integration (; ) that was not able to include these variables.

In sum, the results of this study have shown that resident parents with asymmetric JPC – that is, parents who are their child’s main caregiver and live with their child between 51% and 70% of the time – have small advantages in terms of social well-being when compared to parents with SPC. In contrast, parents with symmetric JPC seem not to benefit from sharing physical custody equally with the other parent when it comes to feelings of loneliness. How can these findings be explained? Resident parents with SPC usually spend more time on childcare tasks than parents who practice JPC which can compete with the parents’ time for leisure and social activities and increase feelings of loneliness. Our analyses suggest that sharing physical custody more equally with the other parent is indeed beneficial for parents with asymmetric JPC in terms of feelings of loneliness. However, if this is the case, one would expect that parents with symmetric JPC profit even more from their physical custody arrangement. This assumption was not confirmed by our analysis, though. One explanation may be that parents with symmetric JPC are a special group of parents who have more obligations and commitments in other life domains (e.g., paid employment). Similarly, they may differ from other parents in terms of how much time they generally invest in childcare, which is why they do not differ significantly from parents with SPC. In addition, these parents may experience spending less time with their children after separation as a loss, which may contribute to feelings of loneliness. In this case, the benefits from spending less time on childcare would be weighed out. Another explanation could be that symmetric JPC is a care arrangement that requires parents not only to spend more money on their children but also to invest substantially more time in childcare and housework than they are accustomed to if they were not their children’s main caregiver prior to separation or divorce, resulting in less time these parents can spend on other activities, including social activities. Therefore, doing gender in marriages (or relationships) and redoing gender through divorce (or separation) with changing conditions and expectations of male and female behavior should get more attention in future research (; ).

This study has several strengths like the use of recent, unique, and rich data on different care arrangements after family dissolution capturing not only the well-being of children but also that of parents. However, like any other empirical study, this study has some limitations. These limitations include the use of cross-sectional data, the consideration of only resident parents, and the fact that we only controlled for the child’s number of transitions but not for certain patterns of parenting time schedules. Furthermore, we only considered families living in Germany, whereas cross-national studies could also help explore the potential relevance of cultural differences.

Given the very scarce research on the relationship between physical custody arrangements and parents’ social well-being (), more research is needed to shed light on this topic and the mechanisms that underly the association – particularly in light of the well-documented consequences that separation and divorce can have for parents’ well-being and the potential implications for the quality of parenting, children’s adjustment to family dissolution, and the quality of the inter-parental relationship (see, e.g., ). Nevertheless, this study has added considerably to the body of literature by revealing a significant relationship between physical custody arrangements and parents’ feelings of loneliness and by showing that differentiating between SPC, asymmetric JPC, and symmetric JPC can be useful when investigating differences between parents living in different types of post-separation families.

Declaration of conflicting interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (394377103).

References

- Amato P. R. (2000). The consequences of divorce for adults and children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(4), 1269–1287. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.01269.x

- Andreasson J., Johansson T. (2019). Becoming a half-time parent: Fatherhood after divorce. Journal of Family Studies, 25(1), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2016.1195277

- Augustijn L. (2022). The intergenerational transmission of psychological well-being – evidence from the German socio-economic panel study (SOEP). Journal of Family Studies, 28(2), 745–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2020.1741427

- Bakker W., Karsten L. (2013). Balancing paid work, care and leisure in post-separation households: A comparison of single parents with co-parents. Acta Sociologica, 56(2), 173–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001699312466178

- Botterman S., Sodermans A. K., Matthijs K. (2015). The social life of divorced parents. Do custody arrangements make a difference in divorced parents’ social participation and contacts? Leisure Studies, 34(4), 487–500. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2014.938768

- Cao H., Fine M. A., Zhou N. (2022). The divorce process and child adaptation trajectory typology (DPCATT) model: The shaping role of predivorce and postdivorce interparental conflict. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-022-00379-3

- de Jong Gierveld J., van Tilburg T. (2006). A 6-item scale for overall, emotional, and social loneliness. Confirmatory tests on survey data. Research on Aging, 28(5), 582–598. https://doi.org/10.1177/0164027506289723

- Gupta K. (2022). Parental well-being: Another dimension of adult well-being. The Family Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/10664807221090948

- Högnäs R. S. (2020). Gray divorce and social and emotional loneliness. In Mortelmans D. (Ed.), Divorce in Europe. New insights in trends, causes and consequences of relation break-ups (pp. 147–165). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25838-2_7

- Jensen T. M., Sanner C. (2021). A scoping review of research on well-being across diverse family structures: Rethinking approaches for understanding contemporary families. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 13(4), 463–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12437

- Kalmijn M., van Groenou M. B. (2005). Differential effects of divorce on social integration. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 22(4), 455–476. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407505054516

- Köppen K., Kreyenfeld M., Trappe H. (2020). Gender differences in parental well-being after separation: Does shared parenting matter? In Kreyenfeld M., Trappe H. (Eds.), Parental life courses after separation and divorce in Europe (pp. 235–264). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44575-1_12

- Kreyenfeld M., Trappe H. (Eds), (2020). Parental life courses after separation and divorce in Europe. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-44575-1

- Recksiedler C., Bernardi L. (2021). Are “part-time parents” healthier and happier parents? Correlates of shared physical custody in Switzerland. In Bernardi L., Mortelmans D. (Eds.), Shared physical custody. Interdisciplinary insights in child custody arrangements (pp. 75–99). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-68479-2_5

- Schnor C., Pasteels I., van Bavel J. (2017). Sole physical custody and mother’s repartnering after divorce. Journal of Marriage and Family, 79(3), 879–890. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12389

- Schoppe-Sullivan S. J., Fagan J. (2020). The evolution of fathering research in the 21st century: Persistent challenges, new directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 175–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12645

- Sodermans A. K., Botterman S., Havermans N., Matthijs K. (2015). Involved fathers, liberated mothers? Joint physical custody and the subjective well-being of divorced parents. Social Indicators Research, 122(1), 257–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0676-9

- Sodermans A. K., Vanassche S., Matthijs K., Swicegood G. (2014). Measuring postdivorce living arrangements: Theoretical and empirical validation of the residential calendar. Journal of Family Issues, 35(1), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X12464947

- Steinbach A. (2019). Children’s and parents’ well-being in joint physical custody: A literature review. Family Process, 58(2), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12372

- Steinbach A., Augustijn L. (2021). Post-separation parenting time schedules in joint physical custody arrangements. Journal of Marriage and Family, 83(2), 595–607. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12746

- Steinbach A., Brocker S. A., Augustijn L. (2020). The survey on “Family models in Germany” (FAMOD). A description of the data. Duisburger Beiträge zur soziologischen Forschung. https://doi.org/10.6104/DBsF-2020-01

- Steinbach A., Helms T. (2020). Familienmodelle in Deutschland (FAMOD). GESIS data archive. Cologne. ZA6849 Data file Version 1.0.0 https://doi.org/10.4232/1.13571

- Vanassche S., Corijn M., Matthijs K., Swicegood G. (2015). Repartnering and childbearing after divorce: Differences according to parental status and custodial arrangements. Population Research and Policy Review, 34(5), 761–784. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11113-015-9366-9

- van der Heijden F., Gähler M., Härkönen J. (2015). Are parents with shared residence happier? Children’s postdivorce residence arrangements and parents’ life satisfaction. Stockholm Research Reports in Demography, 2015, 17.

- van der Heijden F., Poortman A. R., van der Lippe T. (2016). Children’s postdivorce residence arrangements and parental experienced time pressure. Journal of Marriage and Family, 78(2), 468–481. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12283

- Walzer S. (2008). Redoing gender through divorce. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 25(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407507086803