INTRODUCTION

Energy drinks have become an annual 21 billion dollar industry in the USA. Advertisements for these beverages target young adults, particularly men,, making the military population especially prone to energy drink use. The popularity of the drinks in military personnel has been strengthened by their widespread availability during deployments where sleep deprivation is common, with nearly half of deployed troops consuming energy drinks on a daily basis. Research on stateside prevalence rates is limited, and estimates have been hampered by inconsistent methods of determining frequency and quantity of energy drink use. Studies in Air Force personnel and civilian youth suggest that 30–50% use energy drinks regularly,, with 6% consuming them daily.,, Stateside estimates have not been replicated in the Army, despite the fact that soldiers routinely experience inadequate sleep and have higher rates of using other substances compared with Air Force and civilian populations that have been studied.

Energy drink popularity, in general, may be fueled by the desire of young adults to boost their energy levels and to combat fatigue in the short run when they are sleep deprived.,, Consistent with studies on caffeine,, energy drink use has been demonstrated in the lab to result in immediate improvements in cognitive and physical performance. However, it is not clear whether energy drink consumption is tied to mental, emotional, or physical problems. For example, energy drink consumption has been associated with overall daytime sleepiness,, and less sleep at night.– Moreover, findings indicate a link between high energy drink use and stress-related sleep problems suggesting a need to examine the relationship between energy drinks and a range of mental health problems and fatigue. To date, correlations between energy drink use and mental health problems have been inconsistent.,,,– In addition, the degree to which energy drink use impacts overall fatigue levels has not been studied, despite the fact that fatigue mitigation may be a primary goal of energy drink use.,,,

In the military context, characterizing the association of energy drinks with key post-deployment concerns such as mental health problems, aggressive behaviors, and fatigue is particularly important given the negative health sequelae of combat deployment. Understanding these relationships is critical for public health messaging and organizational strategies for the military to sustain and enhance health and readiness. Thus, the present study aims to determine: (1) the prevalence of energy drink use in an Army sample recently returned from a combat deployment; (2) the association between energy drink use and mental health problems, including aggressive behavior; and (3) the association between energy drink use and levels of fatigue.

METHODS

Study Population and Data Collection

As part of a larger study on post-deployment adjustment, we surveyed active duty U.S. soldiers from one brigade combat team after the soldiers returned from a 12-month combat deployment to Afghanistan. This study was approved by an institutional review board at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research. Of 1,322 Soldiers briefed on the study, 1,110 (83.9%) provided written consent to participate in two surveys. The two surveys were administered at 4 and 7 months post-deployment. The current paper focuses on data from the second survey, which was completed by 627 of the 1,110 original participants, a follow-up rate of 56.5% consistent with other studies. The present study analyses this cross-sectional dataset because energy drink items were only included on the second survey. Additional measures in the second survey addressed mental health problems, aggressive behaviors, and fatigue. Surveys were anonymous.

Measures

Background Variables

Rank, age, education, and deployment history were assessed in the first survey.

Energy Drink Use

Frequency of energy drink use was assessed with a question adapted from previous research: “In the past month, how often have you consumed an energy drink (such as: Red Bull, Monster, Rockstar, Amp).” Response options were “None – I don’t drink energy drinks,” “Less than once a week,” “At least once a week, but not every day,” “1 per day,” “2 per day,” “3 per day,” “4 per day,” and “5 or more per day.” Frequency responses were combined into three levels: low (“none” or “less than once a week”), moderate (“at least once a week” or “1 per day”), and high (response options of 2 or more per day).

Energy drink size was assessed with the following question: “What size energy drink do you normally drink?” Besides the response option “I don’t drink energy drinks,” response options were based on common commercial products: (a) “8.4 oz. (such as a small Red Bull),” (b) “16 oz. (such as a small Monster),” and (c) “24 oz. (such as a large Monster).”

Overall volume of energy drink use (in ounces) was determined by multiplying the reported frequency of use by the reported typical size. For the numeric conversion of frequency, “none” was coded as 0, “less than once per week” was coded as 0.14 (maximum of 1 drink per 7 days), “At least once per week, but not every day” was coded as 0.5 (estimated use of half the days of the week), and the other response options of “1 per day” to “5 per day” were coded 1–5, respectively. Once frequency was multiplied by size, the resulting categories based on estimated total volume were grouped into three levels: low (0–4.2 oz./day), moderate (8–16.8 oz./day), and high (24 oz./day or more). This categorization resulted in a logical grouping according to the estimated total volume and was consistent with the overall observed distribution of use and how energy drinks are typically packaged (see Supplemental Table 1).

Mental Health Variables

Mental health variables included sleep problems, depression, anxiety, PTSD, and alcohol misuse. Sleep problems were measured using four items adapted from the seven-item Insomnia Severity Index and used in previous studies with soldiers deploying to combat., Items were “difficulty falling asleep,” “difficulty staying asleep,” both in the past 2 weeks, “How satisfied/dissatisfied are you with your current sleep pattern?,” and “To what extent do you consider your sleep problem to interfere with your daily functioning such as daytime fatigue, ability to function at work/daily chores, concentration, memory, mood, etc.” PTSD was measured using the 17-item version of the PTSD Checklist. The case definition and cut-off criterion were calculated using diagnostic criteria and a total score of at least 50 on a scale of 17–85., Depression was measured with the nine-item Patient Health Questionnaire for Depression; a cut-off was calculated using diagnostic criterion for depression involving at least 5–9 symptoms, including moderate functional impairment. Anxiety was assessed with the seven-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder scale; a cut-off was calculated using a score of at least 10 on a scale of 0–21, including moderate functional impairment. Alcohol misuse was assessed using the three-item version of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. Cut-offs were based on five or more, as reported in previous research with male U.S. veterans.

Aggressive Behaviors

Aggressive behaviors were assessed using a four-item measure., Participants were asked how often in the past month they had engaged in: (a) yelling or shouting, (b) kicking, smashing, or punching something, (c) threatening physical violence, and (d) fighting and hitting someone. Behaviors occurring at least once per month were categorized as scoring positive for that item, consistent with previous studies.

Fatigue

Fatigue was measured with the five-item Acute Fatigue subscale of the Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion Recovery scale, which assessed the energy available for various activities (e.g., family, friends, and hobbies), reserve energy, and being able to recover energy after work. Items were rated on a five-item scale from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Items were averaged such that higher scores indicated greater fatigue.

Data Analysis

Frequencies were computed for all energy drink use items, the five mental health scales, and the four aggressive behaviors. We then used multiple logistic regression to analyze the degree to which energy drink use (low, moderate, and high) was associated cross-sectionally with each mental health problem and aggressive behavior controlling for rank and sleep problems. Linear regression was used to assess the relationship between energy drink use and fatigue, controlling for rank and sleep problems. Each model was run twice: once for energy drink use operationalized as frequency and once as volume. All statistical analyses were completed using R.

RESULTS

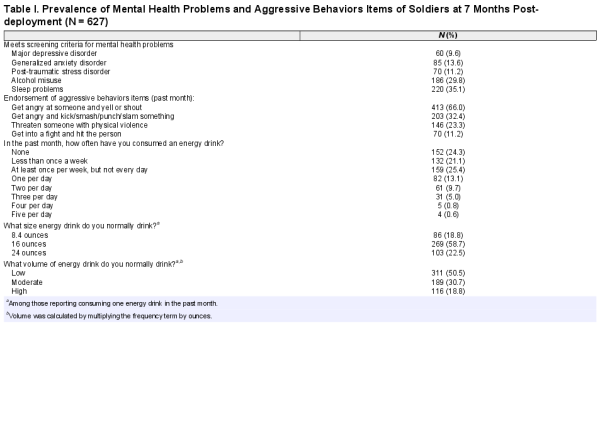

The majority of the sample were 18–24 years old (69.5%), of junior-enlisted rank (E1–E4; 82.6%), had attended some college (37.7%), and were returning from their first deployment (82.1%). The sample was all male. The prevalence rates of mental health problems and aggressive behaviors are presented in Table 1. Rates of mental health problems ranged from 9.6% (depression) to 35.1% (sleep problems). Rates of aggressive behaviors ranged from 11.2% (getting into a fight and hitting someone) to 66.0% (getting angry at someone and yelling or shouting).

Prevalence rates for the frequencies of energy drink use and the size of the typical energy drink consumed are presented in Table 1. About three in four soldiers reported consuming energy drinks (75.7%) with 29.2% reporting at least daily use and 16.7% consuming high levels (2 or more per day). The most common size of energy drink consumed was 16 oz. (58.7%).

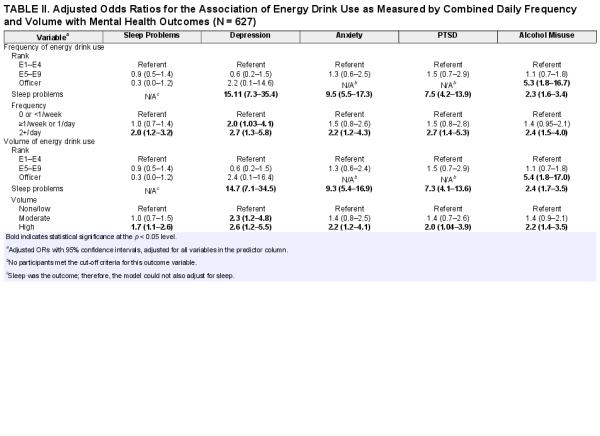

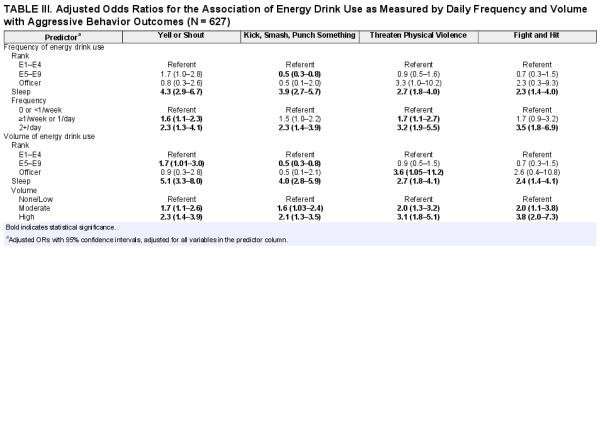

Relative to soldiers in the low frequency group, soldiers in the high frequency group were more likely to exceed criteria for sleep problems, depression, anxiety, PTSD, and alcohol misuse (AORs ranging from 2.0 to 2.7; see Table 2). In addition, the moderate frequency group had greater depressive symptoms compared with the low frequency group (AOR = 2.0, 95% CI = 1.03–4.1). As shown in Table 3, relative to soldiers in the low frequency group, soldiers in the high frequency group were more likely to endorse all four aggressive behaviors (AORs ranging from 2.3 to 3.5). In addition, soldiers in the moderate frequency group were more likely to endorse “yell or shout” and “threaten physical violence,” relative to soldiers in the low frequency group (AORs ranging from 1.6–1.7). In terms of fatigue, both moderate and high energy drink use were associated with heightened fatigue relative to the low use group for frequency (R2 = 0.162, p = <0.001; β = 0.079, p = 0.05; β = 0.143, p = <0.001, respectively).

The patterns seen for high frequency of energy drink use were the same seen for high energy drink use volume. In addition, the moderate use group measured by volume were more likely to endorse each aggressive behavior compared with the low use group (AORs ranging from 1.6 to 2.0). Finally, like the frequency analyses, moderate and high energy drink use volume was significantly associated with fatigue (R2 = 0.168, p = <0.001; β = 0.087, p = 0.03; β = 0.151, p = <0.001, respectively).

DISCUSSION

Seven months following a combat deployment, 75.7% of soldiers reported consuming energy drinks, with 16.1% consuming more than two energy drinks per day. High energy drink use was associated with mental health problems, aggressive behaviors, and fatigue even when controlling for rank and sleep problems. These patterns were consistent across estimated quantitative measures of use (i.e., frequency and volume). In addition, moderate energy drink use was associated with aggressive behaviors and fatigue as well as depressive symptoms.

Daily energy drink use was five times higher in this Army sample (29.2%) than in previous studies of Air Force personnel and youth in the general population (3, 4), and not much lower than the quantity of use reported in a previous study of Army personnel surveyed during a combat deployment (44.8%). It was remarkable that 16% of soldiers in this study reported continuing to consume two or more energy drinks per day in the post-deployment period. In the deployed context, the appeal of energy drinks is understandable given that there is substantial restriction in sleep as well as regular circadian disruption due to night-time operations; indeed, caffeine is a recommended option to sustain alertness in this environment. During the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, energy drinks were often made readily available to deployed service members at no cost. It is unclear, however, whether the high use reported in this post-deployment sample is representative of Army life in general or the result of continuing deployment-related habits.

A key finding was that mental health problems (i.e., depression, anxiety, PTSD, and alcohol misuse) were strongly associated with high levels of energy drink use. Previously, it was unclear whether a link existed between energy drink use and mental health problems,–; the present study provides more evidence for an association of high energy drink use and greater mental health problems. The data from this study also suggest energy drink use is strongly associated with aggressive behaviors. Aggressive behaviors are problematic because of their link to risky behaviors and unhealthy habits, relationship problems, intent to harm others, and suicidal behaviors.

Interestingly, energy drink use was associated with fatigue. This relationship suggests that energy drink use may potentially exacerbate, rather than alleviate, fatigue. This finding stands in contrast to the marketing of energy drinks as a way to increase energy and reduce fatigue. Not only have news outlets and lawsuits challenged whether such claims are valid, but our findings call into question the often-cited rationale for using energy drinks.,, These findings are important to consider from a policy perspective, given the association between protracted fatigue and problems such as poor job performance or making mission critical errors. Future research should examine whether energy drink use results in greater fatigue over time.

Study strengths include addressing shortfalls in previous research through assessments of energy drink frequency, size, and volume, as well as linking energy drink consumption to a range of health indices. Despite these strengths, this paper has several limitations. First, this study is not able to determine causality since the correlations between energy drink use and health outcomes were based solely on one-time point. Thus, energy drinks may lead to an increase in mental health problems, aggression, and fatigue, or energy drink use may be a manifestation of these issues. However, the strength of associations and consistency across outcomes and by energy drink frequency and volume suggest that the associations are relevant. The findings also support the need for further research in this area, particularly longitudinal studies that would allow for stronger assessment of causal relationships. Second, constructs of interest were based upon self-report measures; however, the anonymous survey methods likely facilitated more honest reporting of mental health symptoms. Third, no items assessed other caffeine intake such as soda or coffee; thus, total caffeine intake is likely to be higher than we were able to measure, although it is notable that energy drinks account for a substantially larger proportion of service members’ daily caffeine intake relative to civilian populations. Fourth, our measure of fatigue focused on exhaustion after work rather than during duty hours, which would be of greater concern to commanders. Nonetheless, if a service member is not functioning well at home, this is likely to spillover to work functioning. Fifth, the measures for depression and PTSD each included two items related to sleep and the models were run with sleep problems as a predictor, which could lead to potential confounding in the analyses; however, this is consistent with research in this area.35,36 Sixth, analyses could not take into account individual differences in how energy drinks are metabolized, sleep drive, nor the timing of energy drink consumption relative to attempting to fall sleep, which could all influence the magnitude of the associations. Last, the study did not include measures of nicotine, a potential confounder known to be associated with caffeine intake, although the study did examine alcohol misuse.

This study has implications for clinical treatment and prevention. In terms of clinical treatment, providers should assess energy drink use in this population because its use appears to be associated with mental health problems and aggressive behaviors. Research has found that aggressive behaviors are associated with being less responsive to evidence-based treatments for PTSD. Thus, in order to optimize treatment outcomes, clinicians might also recommend limiting energy drink use during mental health treatment because of the association with aggression.

In terms of prevention, public health messaging should be communicated in a way that targets the reasons why energy drinks are so popular in the first place. That is, although energy drinks are marketed as a way to increase energy and decrease fatigue, overuse of the products may be associated with fatigue. While soldiers may be focused on the short-term gains associated with caffeine use, it is important that they understand the risks associated with overuse. Like with many health-risk behaviors, the message that moderation is critical needs to be conveyed. In addition, military leaders should reconsider how energy drinks are made available in the operational environment to best sustain performance without leading to overuse. Leaders should also consider providing education on reducing use during the transition from deployment.

Integrating treatment, prevention, and organizational strategies that support moderation can lead to a cultural change regarding energy drink use. Such strategies may have a role in reducing high-risk behaviors that are current priorities in the military and may enhance the health of service members.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the assistance of the following former and present Technology Werks contractors to WRAIR: Richard Herrell, PhD, who provided statistical advice, and Juinell Williams, BA and Alexis Dixon, MPH who provided editorial assistance. None of these individuals received compensation for their assistance outside of their salaries.

References

- 1. Stout H: Selling the Young on ‘Gaming Fuel’. New York Times, 2015.

- 2. Adler AB, Britt TW, Castro CA, McGurk D, Bliese PD: Effect of transition home from combat on risk-taking and health-related behaviors. J Trauma Stress2011; 24(4): 381–9.

- 3. Lieberman HR, Tharion WJ, Shukitt-Hale B, Speckman KL, Tulley R: Effects of caffeine, sleep loss, and stress on cognitive performance and mood during U.S. Navy SEAL training. Sea-Air-Land. Psychopharmacology (Berl)2002; 164(3): 250–61.

- 4. Johnson LA, Foster D, McDowell JC: Energy drinks: review of performance benefits, health concerns, and use by military personnel. Mil Med2014; 179(4): 375–80.

- 5. Toblin RL, Clarke-Walper K, Kok BC, Sipos ML, Thomas JL: Energy drink consumption and its association with sleep problems among U.S. service members on a combat deployment – Afghanistan, 2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep2012; 61(44): 895–8.

- 6. Seifert SM, Schaechter JL, Hershorin ER, Lipshultz SE: Health effects of energy drinks on children, adolescents, and young adults. Pediatrics2011; 127(3): 511–28.

- 7. Ishak WW, Ugochukwu C, Bagot K, Khalili D, Zaky C: Energy drinks: psychological effects and impact on well-being and quality of life-a literature review. Innov Clin Neurosci2012; 9(1): 25–34.

- 8. Miller NL, Shattuck LG, Matsangas P: Sleep and fatigue issues in continuous operations: a survey of U.S. Army officers. Behav Sleep Med2011; 9(1): 53–65.

- 9. Bray RM, Pemberton MR, Lane ME, Hourani LL, Mattiko MJ, Babeu LA: Substance use and mental health trends among US military active duty personnel: key findings from the 2008 DoD Health Behavior Survey. Mil Med2010; 175(6): 390–9.

- 10. Ludden AB, Wolfson AR: Understanding adolescent caffeine use: connecting use patterns with expectancies, reasons, and sleep. Health Education & Behavior. 2009.

- 11. Stephens MB, Attipoe S, Jones D, Ledford CJ, Deuster PA: Energy drink and energy shot use in the military. Nutr Rev2014; 72(Suppl 1): 72–7.

- 12. Kamimori GH, McLellan TM, Tate CM, Voss DM, Niro P, Lieberman HR: Caffeine improves reaction time, vigilance and logical reasoning during extended periods with restricted opportunities for sleep. Psychopharmacology (Berl)2015; 232(12): 2031–42.

- 13. Alford C, Cox H, Wescott R: The effects of red bull energy drink on human performance and mood. Amino Acids2001; 21(2): 139–50.

- 14. Waits WM, Ganz MB, Schillreff T, Dell PJ: Sleep and the use of energy products in a combat environment. US Army Medical Department J2014; 22–8.

- 15. Azagba S, Langille D, Asbridge M: An emerging adolescent health risk: caffeinated energy drink consumption patterns among high school students. Prev Med2014; 62: 54–9.

- 16. Kristjansson AL, Sigfusdottir ID, Allegrante JP, James JE: Adolescent caffeine consumption, daytime sleepiness, and anger. J Caffeine Res2011; 1(1): 75–82.

- 17. Trapp GS, Allen K, O’Sullivan TA, Robinson M, Jacoby P, Oddy WH: Energy drink consumption is associated with anxiety in Australian young adult males. Depress Anxiety2014; 31(5): 420–8.

- 18. Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, McGurk D, Castro CA, Hoge CW: Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatry2010; 67(6): 614–23.

- 19. Wilk JE, Quartana PJ, Clarke-Walper K, Kok BC, Riviere LA: Aggression in US soldiers post-deployment: associations with combat exposure and PTSD and the moderating role of trait anger. Aggress Behav2015; 41(6): 556–65.

- 20. Wright KM, Britt TW, Bliese PD, Adler AB, Picchioni D, Moore D: Insomnia as predictor versus outcome of PTSD and depression among Iraq combat veterans. J Clin Psychol2011; 67(12): 1240–58.

- 21. Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA: Psychometric properties of the PTSD checklist (PCL). Behav Res Ther1996; 34(8): 669–73.

- 22. Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL: Combat Duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. N Engl J Med2004; 351(1): 13–22.

- 23. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB: The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med2001; 16(9): 606–13.

- 24. Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Lowe B: A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med2006; 166(10): 1092–7.

- 25. Bush K, Kivlahan DR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD, Bradley KA: The AUDIT alcohol consumption questions (AUDIT-C): an effective brief screening test for problem drinking. Arch Intern Med1998; 158(16): 1789–95.

- 26. Crawford EF, Fulton JJ, Swinkels CM, Beckham JC, Calhoun PS, Workgroup VM-AMOOR: Diagnostic efficiency of the AUDIT-C in US veterans with military service since September 11, 2001. Drug Alcohol Depend2013; 132(1): 101–6.

- 27. Winwood PC, Winefield AH, Dawson D, Lushington K: Development and validation of a scale to measure work-related fatigue and recovery: the Occupational Fatigue Exhaustion/Recovery Scale (OFER). J Occup Environ Med2005; 47(6): 594–606.

- 28. Novaco RW, Swanson RD, Gonzalez OI, Gahm GA, Reger MD: Anger and postcombat mental health: validation of a brief anger measure with U.S. soldiers postdeployed from Iraq and Afghanistan. Psychol Assess2012; 24(3): 661–75.

- 29. Macmanus D, Dean K, Jones M, et al: Violent offending by UK military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a data linkage cohort study. Lancet2013; 381(9870): 907–17.

- 30. Ursano RJ, Colpe LJ, Heeringa SG, Kessler RC, Schoenbaum M, Stein MB: The army study to assess risk and resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS). Psychiatry2014; 77(2): 107–19.

- 31.

- 32. van der Linden D. (2011). The urge to stop: The cognitive and biological nature of acute mental fatigue. In: Decade of Behavior/Science Conference. Cognitive Fatigue: Multidisciplinary Perspectives on Current Research and Future Applications, pp. 149–164. Edited by Ackerman PL. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. doi:10.1037/12343-007.

- 33. LoPresti ML, Anderson JA, Saboe KN, McGurk DL, Balkin TJ, Sipos ML: The impact of insufficient sleep on combat mission performance. Military Behavioral Health2016; 4(4): 1–8.

- 34. Warner CH, Appenzeller GN, Grieger T, et al: Importance of anonymity to encourage honest reporting in mental health screening after combat deployment. Arch Gen Psychiatry2011; 68(10): 1065–71.

- 35. Koren D, Arnon I, Lavie P, Klein E: Sleep complaints as early predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder: a 1-year prospective study of injured survivors of motor vehicle accidents. Am J Psychiatry2002; 159(5): 855–7.

- 36. Luxton DD, Greenburg D, Ryan J, Niven A, Wheeler G, Mysliwiec V: Prevalence and impact of short sleep duration in redeployed OIF soldiers. Sleep2011; 34(9): 1189–95.

- 37. Lloyd D, Nixon R, Varker T, et al: Comorbidity in the prediction of Cognitive Processing Therapy treatment outcomes for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Anxiety Disord2014; 28(2): 237–40.