INTRODUCTION

Participating in academic medical conferences and scientific meetings offers value to both physician trainees (medical students, interns, residents, and fellows) and their faculty. Such events provide a venue for networking and collaboration, mentoring, career advancement, and skill development.

Research is a required component of graduate medical education and many academic medical conferences serve as a forum for disseminating the results of these investigations. Regional meetings in particular offer an opportunity for physician trainees to showcase their work and develop confidence in their research and presentation skills. Presentation at a meeting rewards time and effort invested in research (often outside work hours and with limited ancillary support), allowing residents applying for fellowship training to network and demonstrate academic excellence in a shorter timeframe than achieving publication. Indeed, resident physicians who present at conferences are more likely to conduct and publish future research and pursue fellowship training. Many publications are initially presented at a conference or scientific meeting. While rates vary by meeting, a 2018 Cochrane review of 425 reports which included over 300,000 abstracts identified a publication rate of ~37%.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Armed Forces Annual District Meeting is a regional scientific meeting for current and former military obstetricians and gynecologists and trainees at military and civilian training programs. The meeting only considers unpublished research not previously presented at other venues and features a single poster session on the first day followed by several days of oral sessions. The conference is unique among regional meetings as the district transcends geographical boundaries incorporating attendees stationed across the nation and at various overseas locations. Because the vast majority of participants are active duty personnel who attend on military orders, participation and funding primarily originate through the Department of Defense and changes in funding policy have the potential to impact attendance and the research presented.

To ensure fiscal responsibility to the taxpayer, the U.S. Government (including the Department of Defense) instituted restrictions on conference travel starting in 2012 with required central approval of conference attendance and increased scrutiny at the local command level. While the policy change was designed to prevent abuses that occurred at past federally funded nonmilitary meetings (including a General Services Administration conference featuring $7,000 worth of sushi and a $3,200 fortune telling session), the new policy required additional time and effort for authorization and funding, potentially deterring busy clinicians and trainees from applying. The objective of this study was to determine the academic impact of research presented at the ACOG Armed Forces Annual District Meeting, specifically exploring the effect of policy changes on attendance and the quality and quantity of research presentations.

METHODS

This study was classified as nonhuman subjects research by the Naval Medical Center Portsmouth Institutional Review Board (Portsmouth, Virginia). Attendance logs and meeting programs were provided by ACOG for the 3 years immediately before and after travel regulations were instituted (2009–2014). Attendance rates were determined separately for faculty physicians versus those in training.

Presentations were abstracted from the meeting programs and segregated based on type (oral versus poster). A PubMed search for each abstract was performed between April 2016 and June 2017 to determine if it resulted in publication. Potential PubMed-indexed publications were first identified by searching for the abstract title followed by the presenting author and a search of keywords derived from the presentation title or abstract. The median duration in months from presentation to publication was calculated to determine the typical timeframe and compared between presentation types. The top 10 journals by volume accepting manuscripts presented at the meeting were noted along with the associated Journal Impact Factor (JIF) as determined by Journal Citation Reports 2018 (Web of Science Group, Clarivate Analytics, https://www.annualreviews.org/about/impact-factors/).

Publication rates were compared to reported rates for other conferences identified by literature review. Descriptive statistics and parametric and nonparametric tests were used to compare data where appropriate. A P value <0.05 was deemed significant. Analysis was completed using Stata 11 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas).

RESULTS

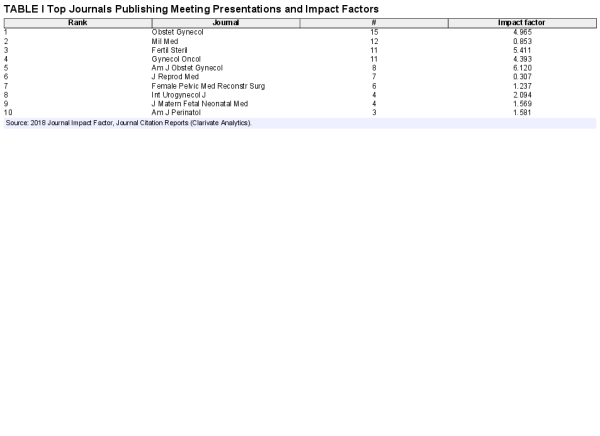

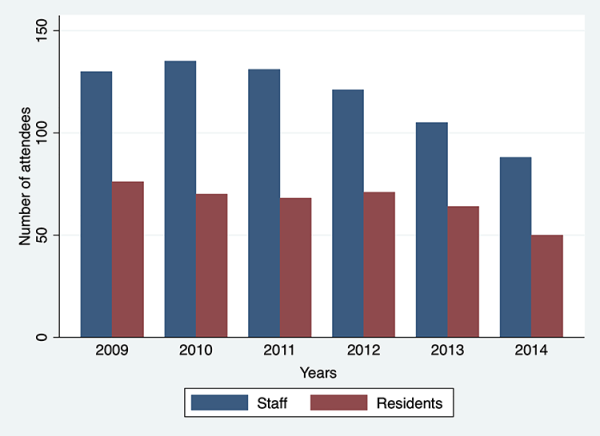

For the 3 years before implementation of stricter travel rules, a mean of 132 faculty attended the meeting annually compared to 105 annually in the 3 years postimplementation (P < 0.05, Fig. 1). In contrast, trainee attendance remained largely stable pre- and postimplementation with mean values of 71 and 62, respectively (P = 0.22).

Figure 1

Staff and resident attendance at the Armed Forces District Meeting from 2009 to 2014.

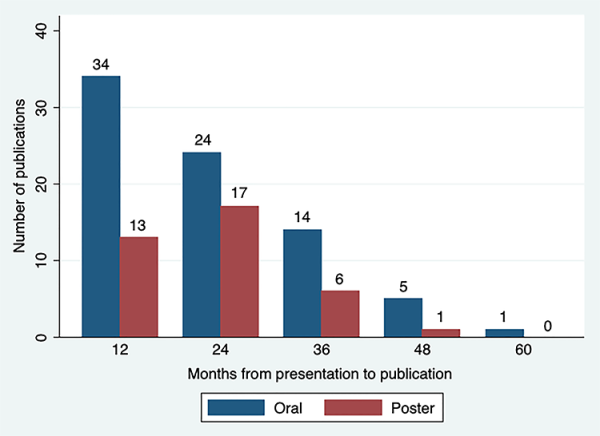

The combined publication rate from the 2009 and 2010 meetings was 23% compared to 16% in 2013–2014 which was not a statistically significant difference in the rates (P = 0.08). Full abstract data for 2010 and 2011 were not available, and 2012 was the year which the new travel rules took effect so these years were excluded for that comparison. The overall publication rate for the Armed Forces District Meeting over the 6 years studied was 22%. For all years reviewed (2009–2014), oral presentations (n = 265) were significantly more likely than poster presentations (n = 260) to result in publications (29 versus 14%, P < 0.001). The median time from presentation to publication did not differ between oral and poster presentations (14.2 versus 14.7 months, P = 0.48, Fig. 2).

Figure 2

Publication rates for poster and oral presentations at the Armed Forces District Meeting. Complete abstract data were not available for 2010 and 2011.

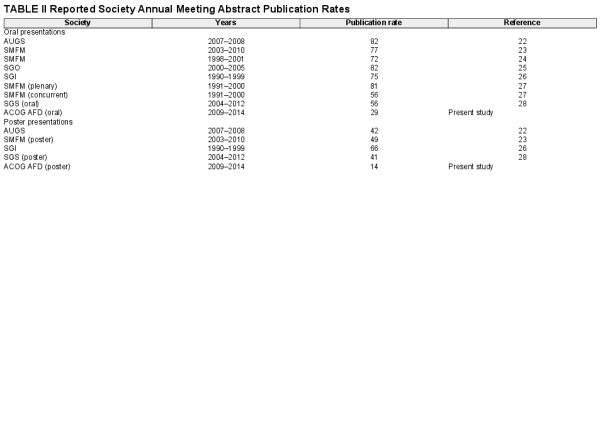

The top journals (by volume) publishing investigations presented at the meeting were Obstetrics and Gynecology (n = 15), Military Medicine (n = 12), and Fertility and Sterility and Gynecologic Oncology (tied, both n = 11). The remaining top journals and associated 2018 impact factors are listed in Table I.

DISCUSSION

This study evaluated the academic impact of research presented at a regional meeting of predominantly active duty U.S. military obstetricians and gynecologists and the implications of more stringent policies on government-funded travel on conference attendance and productivity. Enhanced travel restrictions were associated with decreased faculty physician attendance. Trainee participation and publication rates did not significantly differ.

Our results identify that one in five presentations achieved publication, many in high impact journals within the specialty. Most publications occurred within 1–2 years of presentation supporting our search strategy timeline. Oral presentations were significantly more likely to be published than posters. The presentation to publication rate for the ACOG Armed Forces District Meeting is lower than that of other Obstetrics and Gynecology meetings reported in the literature (Table II); however, this is a comparison of a regional conference to national and international forums. Review of the literature indicates that the publication rate specifically for regional meetings in other specialties ranges from 7 to 50%. A smaller pool of attendees leads to reduced competition for abstract acceptance. Therefore, it is unsurprising that investigations presented at regional meetings have a lower publication rate than their national and international counterparts. We hypothesize that our results indicating a higher publication rate for oral presentations compared to posters is likely because of increased competition for fewer oral slots at most meetings necessitating a higher quality research design.

Academic military physicians face unique challenges compared to their civilian counterparts including deployments, more frequent relocations, and collateral duties which can diminish academic productivity. The weight placed on this academic productivity for promotion differs substantially for the military versus civilian academic environments. Finally, academic military physicians are primarily incentivized for military rank promotion as academic rank promotion is not a requirement to achieve military rank.

Our study has several strengths and some limitations. The study includes several years’ worth of attendance and publication data around a well-defined policy change. Additionally, a single investigator performed all of the PubMed database searches in a systematic fashion, maximizing identification of publications. While conducting the searches using a single investigator has the potential to introduce bias, we believe relying on a pre-specified strategy described in prior studies reduces this risk. We found no other reports of publication rates for research presented at ACOG sponsored meetings.

This study is limited by possible missed publications if there were significant changes in the title or if publication occurred in non-PubMed indexed journals or after completion of the search. As the use of other indexing services like Google Scholar and unique author digital identifiers (like ORCID ID) become more widespread, future research can incorporate these resources to broaden the search. Assessing academic productivity is a complex endeavor. While publication rate and JIF provide an incomplete picture and have limitations, it is a strategy widely employed. Further, research presented but never published diminishes its impact. Finally, we cannot determine if the decrease in staff attendance was the direct result of the policy change or if other factors played a role. Department of Defense conference attendance approval processes have simplified recently, but availability of funds remains a challenge.

Because funding for travel to the ACOG Armed Forces District Meeting primarily originates from a central source, the conference serves as a microcosm for the implications of funding and policy changes on larger academic medical conferences. There is increased scrutiny of the financial and environmental costs of scientific meetings, particularly in resort locations and with advances in technology that allow replacement of travel with videoconferencing. Consequently, there is an ongoing need for studies to quantify the productivity of academic medical conferences and address these concerns. Further, the unique military focus of this women’s health scientific meeting may offer particular value to trainees in military graduate medical education programs. The downstream implication of factors like decreased faculty attendance on trainee professional development, however, is difficult to measure. Local and regional conferences such as this meeting may become more vulnerable to funding and policy changes necessitating further study of their overall value.

CONCLUSION

Approximately one in five presentations at the ACOG Armed Forces District Meeting is published; many are in high impact journals within the specialty. Implementation of stricter travel regulations reduced faculty physician attendance but neither trainee participation nor the publication rate. This, and similar smaller or regional meetings, should continue to be supported as they offer important professional development for students and junior trainees.

This work was presented at the 2017 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Armed Forces District Meeting in San Antonio, Texas.

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of the Air Force, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

The authors are military service members. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. 105 provides that “Copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government.” Title 17 U.S.C. 101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person’s official duties.Categorized as nonhuman subjects research by the Naval Medical Center, Portsmouth, Virginia IRB.

References

- 1. Mata H, Latham TP, Ransome Y: Benefits of professional organization membership and participation in national conferences: considerations for students and new professionals. Health Promot Pract2010; 11(4): 450–3.

- 2. Zierath JR: Building bridges through scientific conferences. Cell2016; 167(5): 1155–8.

- 3. Smiljanic J, Chatterjee A, Kauppinen T, Mitrovic Dankulov M: A theoretical model for the associative nature of conference participation. PLoS One2016; 11(2): e0148528.

- 4.

- 5. Casad BJ, Chang AL, Pribbenow CM: The benefits of attending the annual biomedical research conference for minority students (ABRCMS): the role of research confidence. CBE Life Sci Educ2016; 15(3): ar46,1–11.

- 6. Ahmad HF, Jarman BT, Kallies KJ, Shapiro SB: An analysis of future publications, career choices, and practice characteristics of research presenters at an American College of Surgeons state conference: a 15-year review. J Surg Educ2017; 74(5): 857–61.

- 7. Scherer RW, Meerpohl JJ, Pfeifer N, Schmucker C, Schwarzer G, von Elm E: Full publication of results initially presented in abstracts. Cochrane Database Syst Rev2018; 11: MR000005.

- 8.

- 9. Bhattacharjee Y: Scientific meetings. U.S. agencies feel the pinch of travel cutbacks. Science2012; 338(6107): 595.

- 10. Bowrey DJ, Morris-Stiff GJ, Clark GW, Carey PD, Mansel RE: Peer-reviewed publication following presentation at a regional surgical meeting. Med Educ1999; 33(3): 212–4.

- 11. Duthie AC, Shand AJ, Anderson SM, Hamilton RJ: Experience of an inter-regional research symposium for higher psychiatric trainees in Scotland. Ir J Psychol Med2012; 29(2): 122–4.

- 12. Evans R, Quidley AM, Blake EW, et al: Pharmacy resident research publication rates: a national and regional comparison. Curr Pharm Teach Learn2015; 7(6): 787–93.

- 13. Stranges PM, Vouri SM, Bergfeld F, et al: Pharmacy resident publication success: factors of success based on abstracts from a regional meeting. Curr Pharm Teach Learn2015; 7(6): 780–6.

- 14. Hung M, Duffett M: Canadian pharmacy practice residents' projects: publication rates and study characteristics. Can J Hosp Pharm2013; 66(2): 86–95.

- 15. Drife JO: Are international medical conferences an outdated luxury the planet can't afford? No. BMJ2008; 336(7659): 1467.

- 16. Green M: Are international medical conferences an outdated luxury the planet can't afford? Yes. BMJ2008; 336(7659): 1466.

- 17. Bergeron BP: Let's have a meeting—at your place and mine. Postgrad Med2001; 109(3): 23–7.

- 18. Parthasarathi R, Gomes RM, Palanivelu PR, et al: First virtual live conference in healthcare. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A2017; 27(7): 722–5.

- 19. Roy R: Scientific meetings: call in instead. Science2008; 319(5861): 281–2.

- 20. Ioannidis JP: Are medical conferences useful? And for whom?JAMA2012; 307(12): 1257–8.

- 21. True MW, Bell DG, Faux BM, et al: The value of military graduate medical education. Mil Med2020; 185(5–6): e532–e537.

- 22. Muffly TM, Calderwood CS, Davis KM, Connell KA: The fate of abstracts presented at annual meetings of the American Urogynecologic Society from 2007 to 2008. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg2014; 20(3): 137–40.

- 23. Manuck TA, Barbour K, Janicki L, Blackwell SC, Berghella V: Conversion of Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine abstract presentations to manuscript publications. Am J Obstet Gynecol2015; 213(3): 405 e401–6.

- 24. Brost B, Chauhan SP: Abstract to publication rates for papers presented to the SMFM: how does maternal fetal medicine compare?Am J Obstet Gynecol2005; 193(6): S96.

- 25. Cohen JG, Kiet T, Shin JY, et al: Factors associated with publication of plenary presentations at the Society of Gynecologic Oncologists annual meeting. Gynecol Oncol2013; 128(1): 128–31.

- 26. Gandhi SG, Gilbert WM: Society of Gynecologic Investigation: what gets published?J Soc Gynecol Investig2004; 11(8): 562–5.

- 27. Gilbert WM, Pitkin RM: Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine meeting presentations: what gets published and why?Am J Obstet Gynecol2004; 191(1): 32–5.

- 28. Propst K, O'Sullivan D, Tulikangas P: Quality evaluation of abstracts presented at the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons Annual Scientific Meeting. J Minim Invasive Gynecol2015; 22(6): 1045–8.