INTRODUCTION

There are approximately 1,500 active duty resident physicians in the U.S. Armed Forces, accounting for an estimated 1% of all resident physicians in the United States., They are required to complete training mandated by their branch of service, including in-person and web-based, that are beyond the professional goals and objectives established by their specific residency programs.

These additional requirements offer potential advantages including establishing and promoting military identity, disseminating knowledge critical to the warfighting mission, and assisting in preparing trainees for deployment. However, the number of training requirements and the time needed to complete them may also be a source of fatigue and burnout for resident physicians who have duty hour restrictions.,

The additional training burden for civilian and military residents, and indeed attending physicians and health care professionals in general, is not well reported in the literature. We identified a single publication from the Veteran’s Administration that reported 5.5 hours of required computer-based training every 2 years on information security, harassment, and ethics at a cost of $40 million without clear evidence of benefit.

The primary objective of this study was to quantify all recurring military-specific training that resident physicians in the Armed Forces must complete, stratified by the branch of service. Our secondary objectives were to identify all recurring training (military-specific and general) outside of what is required by individual residency programs and report the number of platforms required to complete this training.

METHODS

We conducted a descriptive study examining fiscal year 2021 recurring training requirements (defined as any requirement that occurred on a repetitive basis, typically annually). The study protocol was submitted to the Clinical Investigations Department at Naval Medical Center Portsmouth (Portsmouth, VA, USA) and deemed exempt from the Institutional Review Board review.

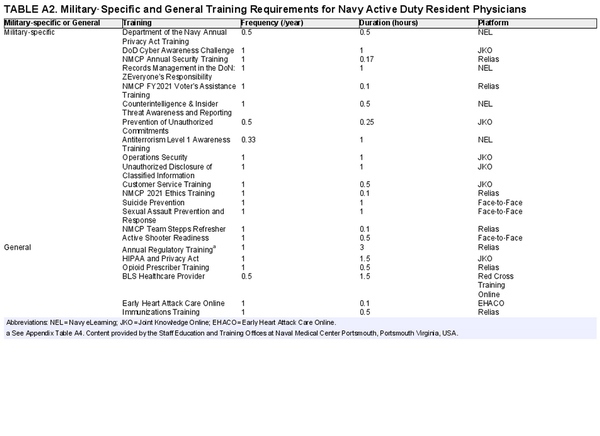

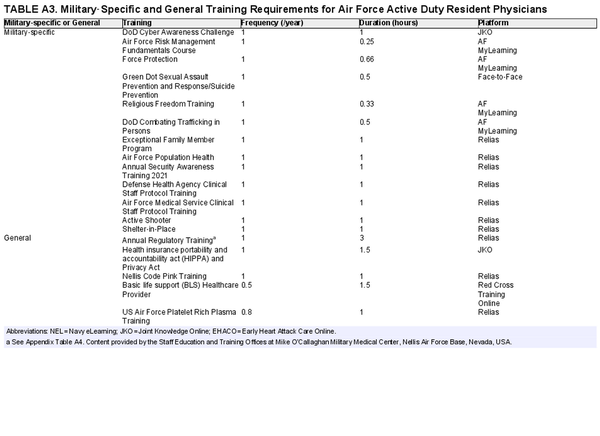

Military-specific training encompassed in-person, and web-based training required specifically of all active duty military personnel such as antiterrorism training, operational security, and cybersecurity. General training predominantly consisted of modules geared toward meeting Joint Commission training requirements such as courses in hospital-mandated infection control, fire safety, whistleblower protections, and health records system training, among others. We excluded non-recurring or single-use training (examples include Financial Literacy Education, Caregiver Operational Stress Control, Work–Life Balance, and Risk Management) because of the heterogeneity of these one-time trainings between sites.

Between March and May 2021, an investigator contacted the staff education and training offices at three military treatment facilities (MTFs) that support at least one residency program: Womack Army Medical Center at Fort Bragg located in Fayetteville, NC; Naval Medical Center Portsmouth in Portsmouth, VA; and Mike O’Callaghan Military Medical Center at Nellis Air Force Base located outside of Las Vegas, NV. These institutions were selected because of the availability of comprehensive training lists. Because military-specific training is standardized across services, single-site training lists from each branch of service were assumed to be representative of all training sites for that branch of service. All required training was collected and tabulated, in addition to descriptions of training requirements and the estimated time to complete them in hours. The time to complete trainings was derived from estimations given on each online platform. Staff education and training offices at each MTF were contacted to obtain the length of in-person trainings. For recurring training mandated less frequently than annually, we divided the hours required to complete by the frequency it was due in years.

Required training documents were organized by the branch of service and parsed into categories of military-specific training and general training. The online training platform service members needed to access for each required training was also recorded.

RESULTS

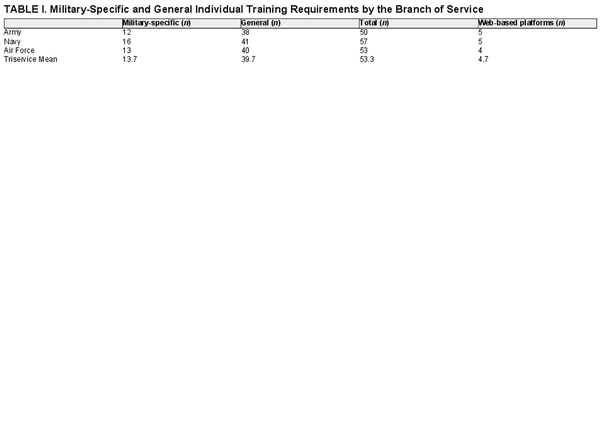

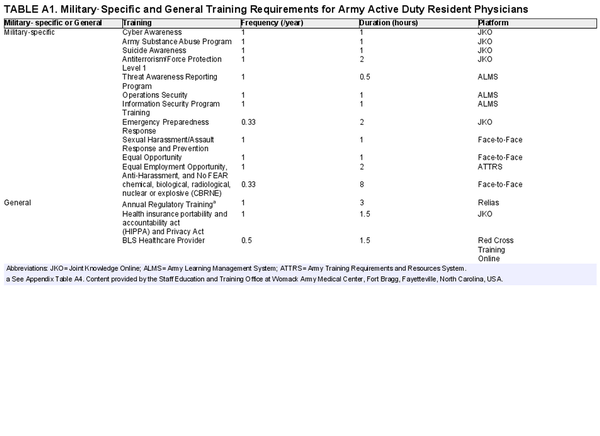

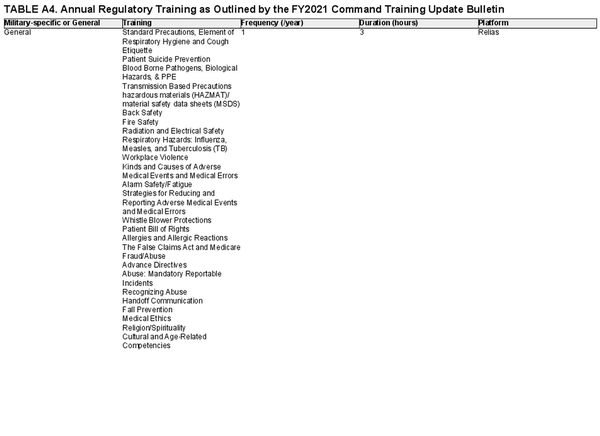

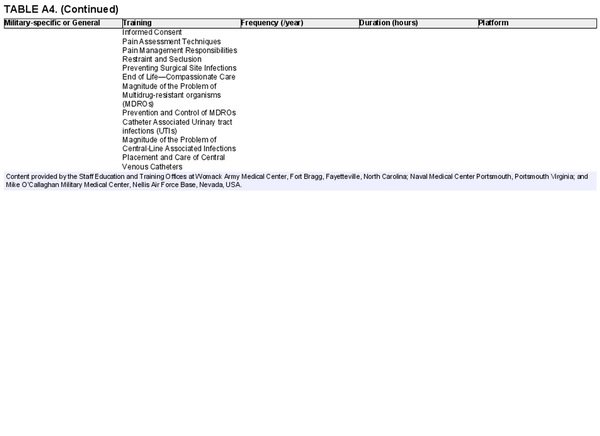

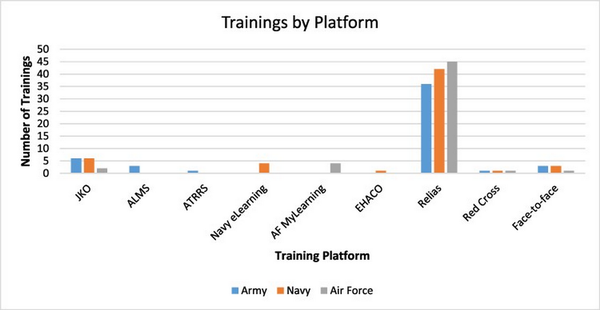

Across the three branches of service, resident physicians were required to complete a mean of 11.2 hours of military-specific training annually. Army resident physicians had the greatest military-specific training requirement in hours per year, estimated at 14.8, followed by their Air Force and Navy counterparts at 10.2 and 8.7 hours, respectively (Fig. 1). These commitments were divided into 12, 16, and 13 individual requirements for Army, Navy, and Air Force resident physicians, respectively. In addition to military-specific training, resident physicians at the MTFs we queried completed a mean of 6.0 hours of general training outside that required by their individual programs (Table I). Cumulatively, active duty resident physicians completed a mean of 17.2 hours of additional training per year excluding one-time training requirements. These were divided into 50, 57, and 53 individual training requirements for those in the Army, Navy, and Air Force, respectively (see Appendix). Of these individual training requirements, 38 general trainings and four military-specific trainings were common to all three branches of service.

FIGURE 1

Total of military-specific online and face-to-face training per year in hours, stratified by service branch.

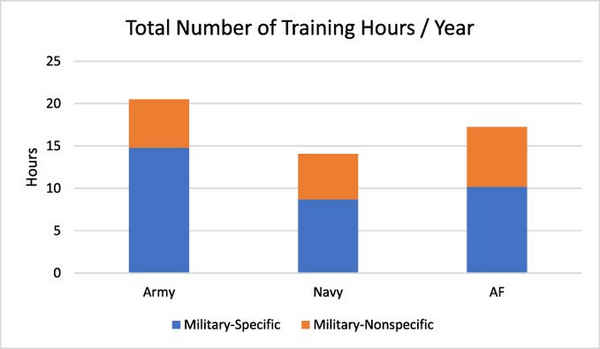

In order to complete the training, resident physicians needed to access four to five unique web-based training platforms in addition to in-person sessions (Fig. 2). For Army resident physicians, this included Joint Knowledge Online (JKO), the Army Learning Management System, the Army Training Requirements and Resource System, Relias, and Red Cross Training Online. For those in the Navy, access to JKO, Navy eLearning, Relias, Red Cross Training Online, and Early Heart Attack Care Online was required. Air Force residents were required to access JKO, Air Force MyLearning, Relias, and Red Cross Training Online.

FIGURE 2

Number of trainings on each platform, stratified by branch of service.

JKO = Joint Knowledge Online, ALMS = Army Learning Management System, ATRRS = Army Training Requirements and Resource System, EHACO = Early Heart Attack Care Online.

To determine their specific requirements, trainees needed to review two to four documents depending upon their branch of service. These included the “Womack Army Medical Center Fiscal Year 2021 Mandated Training Chart,” the “Naval Medical Center Portsmouth Fiscal Year 2021 Command Training Plan,” and the “Air Force Medical Service Training Matrix 2021.” Resident physicians’ training at Nellis needed to review two additional training memos and trainees at all three sites were required to reference the “Annual Regulatory Training Requirements” from the Defense Health Agency.

DISCUSSION

Active duty resident physicians spend the equivalent of more than two work days each year completing additional training requirements. Two-thirds of this training time is unique to their role as military officers.

A portion of this training may aid in establishing military identity and efficiently disseminate information. Yet, training requirements often occur sporadically which can disrupt workflow. Emails prompting the completion of training may warn trainees about upcoming due dates; however, the timeline on which trainings are assigned is often opaque and not standardized. Additionally, there may not be protected time to complete them, meaning training is accommodated in between patient care responsibilities. Furthermore, training may be repetitive from year to year and not necessarily add to one’s functional knowledge.

Precisely identifying every individual requirement, its location, and its time commitment proved complex. A review of the literature demonstrates almost no documentation of the training that resident physicians must complete outside those mandated by their program in other health care systems.

We highlighted earlier that online training requirements have been implicated as a potential contributor to burnout and fatigue for residents and attending physicians.,, Given that these requirements encompass the equivalent of two work days, removing them is unlikely to definitively eliminate burnout. However, viewing this obligation as only 2 days may diminish its true impact. In reality, training is not neatly packaged into two dedicated days where trainees are relieved of other responsibilities. Rather, it occurs episodically, creating chronic interruptions, often in the middle of direct patient care. Therefore, cutting repetitive or non-value added training may be a “low hanging fruit” in a multifaceted approach to reducing burnout and promoting provider wellness.

Our study has some limitations. For example, it does not provide a complete picture of all in-person and web-based training required of military resident physicians as we excluded non-recurring requirements. Based on correspondence with training departments, we estimate resident physicians complete up to 12 hours of additional one-time training throughout the year. Additionally, our results do not factor in time spent tracking the list of requirements or uploading/emailing the training certificates for documentation or the time burden of working across multiple non-reciprocating platforms. We were unable to account for other items that take time, such as password resets or repetitive attempts to log in to websites that are down. Finally, we did not quantify the time lost for direct patient care because of mandated training or the relative value of this training versus direct patient care.

Future research could explore the impact of this training burden on other health care professionals, morale and patient care, and query if individual programs provide dedicated time to complete required training. For example, many military residency programs have dedicated academic time on a weekly basis and a portion of that time could be protected for required training.

The recent consolidation of individual Army, Navy, and Air Force MTFs into a unified Military Health Care System overseen by the Defense Health Agency offers an opportunity to standardize training requirements, identify what information is most efficiently distributed through training, and streamline the process by placing training in a single web-based platform with centralized tracking and visual cues for deadlines, such as what used to exist on the AMEDD Personnel Education and Quality System. Infrastructure for this may already exist via the JKO or Relias platforms, both of which are accessed by the three service branches for most of their training requirements. This centralized tracking system should be easily accessible to mitigate the need to “email your certificate” to every office that needs a copy and should digitally follow a service member from one duty station to another. Given that military resident physicians cumulatively spend over 25,000 hours completing training annually, these changes could result in more time for patient care.

CONCLUSIONS

In summary, active duty Army, Navy, and Air Force resident physicians are required to complete a mean of 17.2 hours of training annually, of which 11.2 hours was military-specific. Trainees needed to access four to five web-based platforms to complete an average of 53 individual requirements. Ongoing interest in provider wellness, consolidation of service-specific assets, and increased need to optimize access to patient care all offer compelling reasons for the Defense Health Agency to scrutinize current training requirements and the means by which they are tracked and delivered to determine what is “value added” versus “headache inducing.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

None declared.

Training Requirement Data

REFERENCES

- 1. Heisler E.J. et al: Federal support for graduate medical education: an overview. Congressional Research Service, ed. Available at https://crsreports.congress.gov/2018; accessed June 29, 2021.

- 2. He K, Whang E, Kristo G: Graduate medical education funding mechanisms, challenges, and solutions: a narrative review. Am J Surg 2021; 221(1): 65–71.

- 3. Nagy CJ: The importance of a military-unique curriculum in active duty graduate medical education. Mil Med 2012; 177(3): 243–4.

- 4. Summers SM, Nagy CJ, April MD, Kuiper BW, Rodriguez RG, Jones WS: The prevalence of faculty physician burnout in military graduate medical education training programs: a cross-sectional study of academic physicians in the United States Department of Defense. Mil Med 2019; 184(9–10): e522–30.

- 5. Simons BS, Foltz PA, Chalupa RL, Hylden CM, Dowd TC, Johnson AE: Burnout in U.S. military orthopaedic residents and staff physicians. Mil Med 2016; 181(8): 835–9.

- 6. Peterson K, McCleery E: Evidence brief: the effectiveness of mandatory computer-based trainings on government ethics, workplace harassment, or privacy and information security-related topics. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. In: VA Evidence Synthesis Program Evidence Briefs. 2011; 12–14.

- 7. Verougstraete D, Hachimi Idrissi S: The impact of burn-out on emergency physicians and emergency medicine residents: a systematic review. Acta Clin Belg 2020; 75(1): 57–79.