INTRODUCTION

Although they are an uncommon cause of cough and shortness of breath in young active duty personnel, mediastinal masses are potentially life-threatening conditions that should be considered in the evaluation of these patients. One example is a primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL), an aggressive lymphoma that accounts for 2%-3% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas. This diagnosis is most commonly made in those 30-40 years old and has a female predominance. The clinical presentation is often a bulky anterior mediastinal mass that can invade adjacent structures, including lungs, pleura, and pericardium, and present symptoms related to mediastinal compression: cough, shortness of breath, superior vena cava (SVC) obstruction, and pleural or pericardial effusions. Treatment of these masses requires coordination between multiple specialists as well as urgent transfer to intensive care for appropriate monitoring during management. With respect to treatment, chemotherapy with the more aggressive dose-adjusted chemotherapy regimen (DA) EPOCH-R (rituximab, etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, and doxorubicin) has shown improved event-free survival rates compared to the chemotherapy regimen known as the R-CHOP regimen (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) with or without radiation therapy. We present a case of PMBCL in an active duty patient referred to pulmonary clinic 5 weeks after being evaluated at sick call on his ship.

CASE PRESENTATION

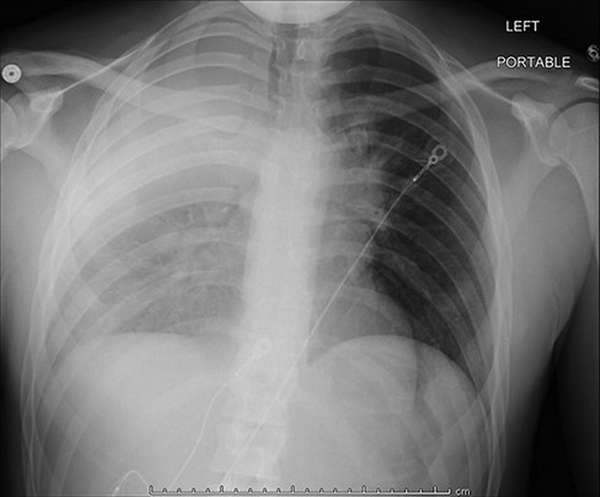

A 23-year-old male sailor surface warfare officer was initially evaluated by his primary care provider at sick call on a missile destroyer in port for a 5-month history of shortness of breath, night sweats, cough with occasional hemoptysis, and several pruritic punched-out lesions on his hands and lower extremities. He was also found to have an unintentional 50-pound weight loss in the past year; while the patient noted that his uniforms had not been fitting as well as they had previously, he had not sought medical attention for his weight loss. Chest radiograph demonstrated persistent opacification of the right upper and middle lobes and nodules projecting over the right middle lobe (Fig. 1). Following the appointment, a referral to pulmonology clinic at Tripler Army Medical Center was placed for further evaluation for what was initially thought to be because of an infectious versus an inflammatory process, with the patient presenting to pulmonology clinic 5 weeks following his initial appointment on his ship.

FIGURE 1

Chest X-ray taken before presentation to pulmonary clinic demonstrating persistent opacification of the right upper and middle lobes and nodules projecting over the right middle lobe.

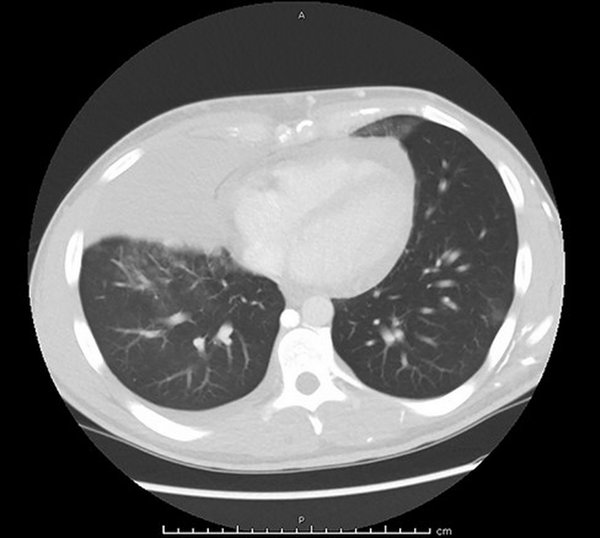

A chest computed tomography (CT) scan obtained immediately following his pulmonary clinic visit revealed a mediastinal mass causing compression of both the right bronchus and the SVC with a large pericardial effusion (Fig. 2). Labwork conducted following his CT scan was notable for a lactate dehydrogenase value nearly twice the upper limit of normal (522 units/L).

FIGURE 2

Chest computed tomography (CT) obtained before admission showing a large mediastinal mass measuring 17.5 cm × 15 cm with a pericardial effusion.

He was directly admitted to the intensive care unit from the pulmonary clinic for critical airway management, given the risk of acute airway compromise requiring emergent intervention. An echocardiogram demonstrated a moderate, non-complex, circumferential pericardial effusion with right atrium collapse, dilated inferior vena cava, and mild right ventricle early diastolic collapse concerning for early cardiac tamponade. A pericardiocentesis with pericardial drain placement was promptly performed. The pericardial effusion cytology studies demonstrated a lymphoid proliferation with reactive mesothelial cells; no malignant cells were identified.

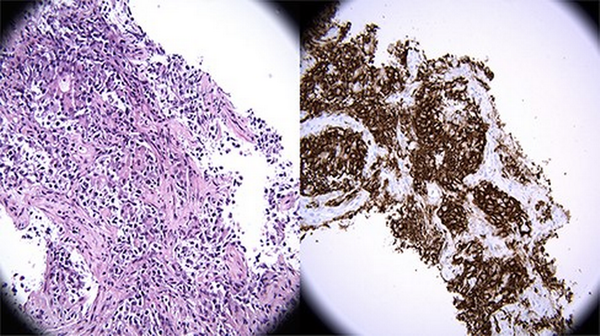

High-dose dexamethasone treatment was initiated for empiric treatment of lymphoma to reduce the mediastinal mass as there was a concern for impending airway compromise while diagnostic testing was still pending. An ear, nose, and throat specialist was consulted for possible cervical lymph node biopsy, but none of the lymph nodes viewed on neck ultrasound were deemed amenable to biopsy. Following discussion with multiple specialists from anesthesia, hematology/oncology, critical care, and thoracic surgery, the decision was made to pursue ultrasound-guided biopsy of the mediastinal mass while deferring bronchoscopy due to the risk of cardiopulmonary collapse associated with intubation. On hospital day 3, an ultrasound-guided biopsy of the anterior mediastinal mass was performed under local sedation. The biopsy revealed an atypical lymphoid infiltrate associated with a background of compartmentalizing fibrosis. The infiltrate was predominantly atypical lymphoid cells, primarily large cells with ovoid to irregular nuclei, dispersed chromatin, variably prominent nucleoli, and scant to moderate pale to clear cytoplasm (Fig. 3A). Immunostains performed on the lymphoid infiltrate were diffusely positive for the B-cell antigen (CD20), as well as multiple protein-coding genes including the transcription factor paired box 5 (PAX5), BCL2, Multiple Myeloma Oncogene 1 (MUM1), and BCL6, and had weak focal positivity for CD30 (Fig. 3B). Immunostains were negative for CD3, CD5, CD10, CD117, cyclin D1, and cytokeratin AE1/AE3. Ki-67 (MIB-1), a protein only present in actively proliferating cells, was found to be elevated with a 70% proliferation index. A study for the Epstein–Barr encoding region by in situ hybridization was negative. These findings led to the diagnosis of PMBCL. The chest, abdomen, and pelvis staging CT revealed multiple ground-glass pulmonary nodules within the bilateral lower lobes and splenomegaly.

FIGURE 3

(Left) (A) Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain 400×: High-power view of infiltrative lymphoid proliferation composed of large, atypical lymphocytes with large, hyperchromatic nuclei and clear to amphophilic cytoplasm. The cells form packets separated by bands of fibrosis and are insinuating into the lung airspaces (X400, H&E). (Right) (B) Immunohistochemistry (IHC) stain 400×: High-power view of CD20 immunohistochemical stain. CD20 strongly and diffusely highlights the large malignant lymphoid proliferation, with staining localizing within the cytoplasm and cell membrane. The small, background T-lymphocytes do not express CD20. Taken with the histomorphology, this immunophenotype is consistent with a diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (X400, CD20).

On hospital day 6, following the initial pericardiocentesis, an echocardiogram revealed resolution of the pericardial effusion and right atrial and ventricular diastolic collapse. However, it demonstrated a persistently dilated inferior vena cava. On hospital day 9, the patient began DA-EPOCH-R as per the Children’s Oncology Group protocol for non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma known as ANHL1931 Arm A for PMBCL. The patient remained afebrile and had no evidence of tumor lysis syndrome or airway issues throughout his hospital stay. Additionally, the pruritic punched-out skin lesions were presumed to be secondary to a paraneoplastic process associated with the underlying lymphoma. Treatment was pursued with a regimen of topical corticosteroids, H1 receptor antagonists, and gabapentin. He was discharged on hospital day 15.

A positron emission tomography/CT scan was obtained 1 week after discharge. The findings demonstrated a fluorodeoxyglucose avid anterior mediastinal mass with hypermetabolic bilateral pulmonary nodules. Following his initial admission, he remained clinically stable. He tolerated his second cycle without any complications. Furthermore, his pruritus resolved approximately 6 weeks after the initiation of chemotherapy. After completing cycle 2 without appropriate neutrophil recovery, he was transferred to a medical oncology facility to complete the remainder of his planned chemotherapy cycles within the mainland USA to ensure that the patient had adequate familial support during his chemotherapy treatment.

DISCUSSION

The initial differential diagnosis for a mediastinal mass is quite broad. This differential includes primary mediastinal tumors such as thymomas, thyroid tumors, germ cell tumors, other lymphomas that localize to the mediastinum, and other cancers that may have metastasized to the mediastinum. In addition, the mediastinal mass can cause direct cardiopulmonary compression, which may make a prompt definitive diagnosis difficult. When such a case initially presents in an outpatient setting with limited available diagnostic modalities, this can further complicate and delay the diagnosis. In this case, the patient initially presented to his primary care provider in a resource-limited environment with worsening dyspnea, chronic cough with intermittent hemoptysis, significant weight loss, and diffuse pruritic lesions on all extremities. The definitive workup ultimately required inpatient admission and collaboration from multiple subspecialists at a military treatment facility. This case describes a relatively rare oncologic condition in the active duty population and demonstrates the critical role the primary care provider has in facilitating a comprehensive workup and treatment.

Patients with these large, rapidly growing tumors can present with weight loss, cough, dyspnea, and hoarseness. As seen in our patient, they may also have associated pleural or pericardial effusions, SVC syndrome, and an elevated lactate dehydrogenase level. In two-thirds of cases, PMBCL presents as a bulky mass in the anterior mediastinum with associated SVC syndrome and airway obstruction. However, only one-third of patients have constitutional symptoms. This case highlights the need to include malignancy on the differential for any young active duty patient presenting with similar symptoms, especially unexplained weight loss. In addition, our patient’s dermatologic lesions on his extremities are not commonly associated with PMBCL but are a paraneoplastic phenomenon more commonly seen in other types of cancers. While pruritus is more commonly associated with Hodgkin’s lymphomas, prevalent in around 30% of cases, some studies have estimated the rate of pruritus in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas to be between 1% and 15%., As its clinical presentation can mimic several other conditions, the diagnosis of PMBCL as per 2017 World Health Organization criteria requires biopsy of the tumor in order to make the diagnosis. Once biopsy and antigen testing were obtained, it was found that our patient fulfilled World Health Organization criteria for the diagnosis of PMBCL, including one major criterion (anterior mediastinal mass with or without lymph node involvement, no extranodal disease, B-cell antigen expression, and Epstein–Barr virus negativity) and at least one supporting feature (weak positivity for CD30).

Diagnostic challenges commonly occur in patients with a mediastinal mass. On admission, a chest CT scan found the tumor compressing the right bronchus and SVC, increasing the risk for acute airway compromise. As a result, multiple precautions were taken throughout the patient’s admission to minimize this risk, such as elevating the head of the patient’s bed and avoiding sedating medications whenever possible. Our patient received only local sedation for his biopsy with interventional radiology. It is essential for military providers administering medical care in isolated or resource-limited regions to identify patients who present with a mediastinal mass and implement these precautions. Additional precautionary measures to take include avoiding the supine position. Prompt early consultation with oncologists and intensivists should be initiated to coordinate transfer to a higher level of care.

Once PMBCL is identified, there is ongoing research to determine prognosis and optimal treatment. Recent studies have identified multiple risk factors in PMBCL associated with worse outcomes that are present in this patient, including metastatic disease to the lungs, presence of a pericardial effusion, a Ki-67 proliferation index greater than or equal to 70%, and a mediastinal mass greater than 10 cm in width., Ultimately, an appropriate workup under the supervision of an oncologist is needed to comprehensively characterize the extent and severity of the disease. Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) remains a rare lymphoma with little follow-up data from large studies on newer treatment regimens. There is controversy on which of the two leading treatment regimens should be used. R-CHOP was the first-line therapy for PMBCL before 2013, with a study from 2011 showing the R-CHOP regimen to have a 3-year event-free survival rate of 78%. In 2013, a phase II trial using DA-EPOCH-R conducted in 2013 demonstrated a 5-year event-free survival rate of 93%, with only 4% of patients requiring consolidated radiotherapy, making it a standard of care for many treatment centers globally. For a young service member with a non-recurrent or refractory PMBCL, maximizing years of event-free survival provided a compelling reason to utilize this regimen. While treatment of newly diagnosed cases of PMBCL is typically treated with R-CHOP or DA-EPOCH-R, novel therapies such as pembrolizumab, brentuximab, and nivolumab combination therapy and ruxolitinib are currently being researched for treatment of refractory or relapsing PMBCL. In particular, phase III trials on the use of pembrolizumab in recurrent or refractory PMBCL have demonstrated improved response rates compared to the current standard treatment of stem cell transplant. While DA-EPOCH-R’s increased 5-year survival rate is promising, more research on the long-term effects and survival of PMBCL as well as new novel therapies is needed to determine if DA-EPOCH-R should remain the standard therapy.

CONCLUSIONS

A rare but life-threatening mediastinal tumor, primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma most commonly occurs within the age range of the active duty population and poses significant risk for rapid cardiopulmonary compromise and death. As many remote military clinical settings do not have access to the appropriate interventions to treat life-threatening complications of large mediastinal masses such as pericardiocentesis and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, early identification of a potential mediastinal mass and transfer is crucial to avoid decompensation. This case demonstrates that all military primary care providers should be educated to identify constitutional symptoms as well as potential masses on chest X-ray during formal medical training, such as during Independent Corpsman School for Navy personnel or Combat Medic School for Army medics. In addition, these providers should be instructed that they need to urgently refer patients to higher-level care for further evaluation if a mediastinal mass is suspected. Constitutional symptoms such as fevers, night sweats, unexplained weight loss, and fatigue should be incorporated as a unique section into the review of systems for periodic health assessments, and providers should counsel service members during the in-person component of the periodic health assessment to monitor themselves for these symptoms as they may be signs of cancer. Finally, consulting with the appropriate subspecialists early is essential in patients with a mediastinal mass in order to initiate empiric treatment, minimize risk of cardiopulmonary collapse, and coordinate urgent transfer to higher-level care.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Lees C, Keane C, Gandhi MK, Gunawardana J: Biology and therapy of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: current status and future directions. Br J Haematol 2019; 185(1): 25–41.doi: .

- 2. PDQ® Adult Treatment Editorial Board: PDQ adult non-Hodgkin lymphoma treatment. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute. Available at https://www.cancer.gov/types/lymphoma/hp/adult-nhl-treatment-pdq, January 18, 2022; Accessed February 27, 2022.

- 3. Savage KJ: Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Oncologist 2006; 11(5): 488–95.doi: .

- 4. Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Maeda LS, et al.: Dose-adjusted EPOCH-rituximab therapy in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(15): 1408–16.doi: .

- 5. Hayden AR, Tonseth P, Lee DG, et al.: Outcome of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma using R-CHOP: impact of a PET-adapted approach. Blood 2020; 136(24): 2803–11.doi: .

- 6. Soumerai JD, Hellmann MD, Feng Y, et al.: Treatment of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone is associated with a high rate of primary refractory disease. Leuk Lymphoma 2014; 55(3): 538–43.doi: .

- 7. Giulino-Roth L, O’Donohue T, Chen Z, et al.: Outcomes of adults and children with primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma treated with dose-adjusted EPOCH-R. Br J Haematol 2017; 179(5): 739–47.doi: .

- 8. Carter BW, Benveniste MF, Madan R, et al.: ITMIG classification of mediastinal compartments and multidisciplinary approach to mediastinal masses. Radiographics 2017; 37(2): 413–36.doi: .

- 9. Yu Y, Dong X, Tu M, Wang H: Primary mediastinal large B cell lymphoma. Thorac Cancer 2021; 12(21): 2831–7.doi: .

- 10. Chen H, Pan T, He Y, et al.: Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: novel precision therapies and future directions. Front Oncol 2021; 11: 654854.doi: .

- 11. Krajnik M, Zylicz Z: Understanding pruritus in systemic disease. J Pain Symptom Manage 2001; 21(2): 151–68.doi: .

- 12. Yosipovitch G: Chronic pruritus: a paraneoplastic sign. Dermatol Ther 2010; 23(6): 590–6.doi: .

- 13. Fairchild A, McCall CM, Oyekunle T, et al.: Primary mediastinal (thymic) large B-cell lymphoma: fidelity of diagnosis using WHO criteria. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 2021; 21(5): e464–9.doi: .

- 14. Zhou H, Xu-Monette ZY, Xiao L, et al.: Prognostic factors, therapeutic approaches, and distinct immunobiologic features in patients with primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma on long-term follow-up. Blood Cancer J 2020; 10(5): 49.doi: .

- 15. Giulino-Roth L: How I treat primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2018; 132(8): 782–90.doi: .

- 16. Martelli M, Ferreri A, Di Rocco A, Ansuinelli M, Johnson PWM: Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2017; 113: 318–27.doi: .

- 17. Rieger M, Österborg A, Pettengell R, et al.: Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma treated with CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab: results of the Mabthera International Trial Group study. Ann Oncol 2011; 22(3): 664–70.doi: .

- 18. Dunleavy K, Steidl C: Emerging biological insights and novel treatment strategies in primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Semin Hematol 2015; 52(2): 119–25.doi: .