In recent years, there has been a sustained increase in the number of residency applications per student, particularly for competitive specialties such as otolaryngology. During the 2020‐2021 residency application cycle, an average of 77.69 Electronic Residency Application Service (ERAS) applications were submitted per US MD otolaryngology applicant, as opposed to 61.15 in the 2019‐2020 residency application cycle. During the same period, otolaryngology residency programs received an average of 345.02 ERAS applications from US MD applicants versus 297.86 in 2019‐2020. These figures contradict guidance from the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) that suggests a point of diminishing returns for matching with submission of additional applications based on one’s United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) Step 1 score. For otolaryngology US MD applicants, that point of diminishing returns is 28 applications with a Step 1 score ≥252, 45 with a score from 241 to 251, and 48 with a score ≤240. In addition to being costly, the increased number of applications does not change the annual match rate and thus contributes to match inefficiency.

The surge of otolaryngology residency applications may in part be due to candidates struggling to identify the factors that make them competitive. Their perception of important factors and the relative weight of those factors in the application process often misaligns with the perception of residency selection committees. This lack of clarity fuels a fear of not matching and fosters the belief that more applications are better. In an effort to end this “arms race,” the AAMC Undergraduate Medical Education to Graduate Medical Education Review Committee recently penned a report with recommendations including the guidance for programs to provide more information so that candidates may better understand where they have a chance for interview or acceptance.

Applicants often turn to the internet to seek information about otolaryngology residency programs, a trend expected to increase in the setting of virtual application cycles resulting from the COVID‐19 pandemic. While research on this topic area is limited in otolaryngology, a survey of emergency medicine applicants demonstrated that >75% of respondents noted that information found on residency programs’ websites influenced their decision to apply to those programs. Additionally, a survey of interventional radiology applicants discovered that the most important source of information for applicants was the program’s website, even ahead of information from physicians and mentors.

Previous work in otolaryngology has examined the content areas on residency program websites, including clinical training, research opportunities, didactics, and incentives. However, this information is less helpful for applicants wanting to assess their competitiveness at particular residency programs. Our objective was to evaluate otolaryngology residency programs’ websites for information pertaining to the application process, including requirements, screening and/or selection, and average interviewee or matched resident statistics.

Methods

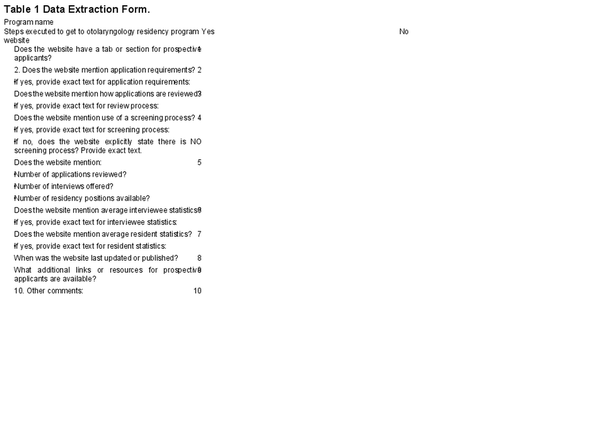

We conducted a systematic content analysis of the websites of the top 50 otolaryngology programs as defined by reputation on Doximity Residency Navigator from June to July 2021. Two researchers (N.M.M. and B.A.G.) independently evaluated each website and collected information into separate data extraction forms (Table1). We assessed each otolaryngology department’s home website for direct links or drop‐down menu options for education and/or residency program information for applicants. Data extraction forms were compared to ensure consistency. Any discrepant data resulted in a return to the website and a discussion among researchers until consensus was met. The University of Michigan institutional review board deemed this study not regulated, as human subjects were not involved.

Results

All otolaryngology residency programs analyzed (N = 50) had a website dedicated to prospective applicants through a link on the homesite to “education,”“residency program,”“application process,” or a variation and/or combination of these elements. The websites had copyrights of 2021 (n = 43, 86%), 2020 (n = 2, 4%), and 2018 (n = 1, 2%). Copyright was not provided in 4 cases (8%).

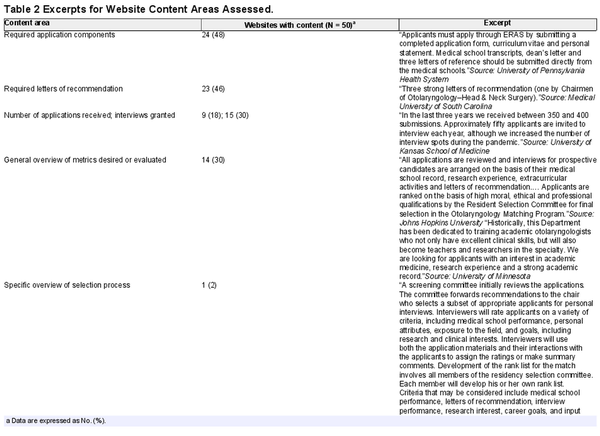

Just under half the websites (n = 24, 48%) explicitly listed required application components (eg, ERAS common application, personal statement, medical school transcript), while the remainder (n = 26, 52%) simply stated that applications were accepted through ERAS. Just 23 websites (46%) mentioned the desired number of letters of recommendation, and only 2 (4%) noted a specific need for a letter written by the chair of the applicant’s home otolaryngology department (Table2). One website mentioned that a chair’s letter was not necessary.

All websites included the number of residency positions available. However, just 9 websites (18%) provided the number of applications received and the number of interviews granted. These numbers typically ranged between 300 and 400 applications received and 40 to 50 interviews granted for 3 to 5 residency positions. An additional 6 websites (12%) provided only the number of interviews granted.

Most websites (n = 35, 70%) did not describe the process that the residency selection committee uses to evaluate candidates for residency positions. A minority of programs (n = 14, 30%) provided very general information for metrics on which candidates are scored or ranked in the application process (eg, medical student performance, research interests). This content ranged from broad professional and personal qualities to more specific career goals and interests. One exception was the University of Washington, which provided a relatively detailed overview of its residency selection process. Nearly all websites (n = 49, 98%) did not mention the screening processes in place to select applicants for interview. Only 6 websites (12%) explicitly mentioned that USMLE Step score cutoffs are not used, while 3 others (6%) made vague statements indicating that every ERAS application is reviewed. For 2 of the 6 websites indicating that USMLE Step score cutoffs are not used, one stated that the score was used as a factor in the selection process, and the other stated that its applicants have an average Step 1 score of 235. One program mentioned the use of USMLE scores to narrow down the applicant pool; however, it did not provide the exact score that it used to screen applicants in or out of consideration.

Zero programs provided information about the demographics or academic characteristics of their interviewed applicants (eg, medical student performance, USMLE Step scores, research experience). One program made a general statement regarding the usual profile of an otolaryngology applicant. Most websites did not provide any information regarding the demographics or academic characteristics of their residents. Two websites (4%) provided general statements regarding the characteristics of the applicants chosen for residency at those programs. The exception to the trend described was The Ohio State University, which provided matched residents’ application statistic averages for the preceding 5 years from 2015 to 2020.

The most common external links were to the websites for ERAS (n = 29, 58%) and/or the National Resident Matching Program (n = 24, 48%). Boston University Medical Center provided a general section titled “How Do I Match in Otolaryngology?” with an external link to the American Academy of Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Foundation with additional information.

Discussion

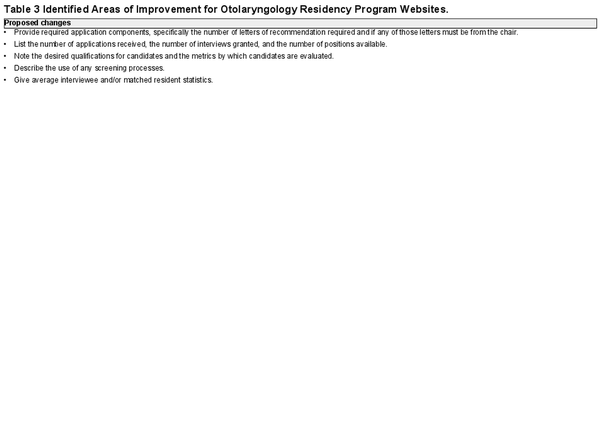

Our study demonstrates the limited information available on departmental otolaryngology websites pertaining to the residency application process, highlighting opportunities for improvement (Table3). First, a minority of programs provided candidate metrics desired or evaluated by the residency selection committee. When stated, such metrics were broad professional and personal qualities, such as “record of academic excellence” and “good communication skills,” rather than specific qualifications. A few select program websites stated a preference for strong research backgrounds and a goal of training academic otolaryngologists. While acknowledging that the vagueness or outright lack of information is likely a consequence of the holistic review process in place at many programs, institutions still may provide the desired qualifications for residents selected to train at their programs in line with their programs’ missions. This practice would be particularly valuable for programs with unique aims, such as producing physician‐scientists, promoting diversity, or serving certain patient populations (ie, urban or rural health).

Second, most programs made no mention of the screening processes in place to narrow the initially large pool of applications to one that is more manageable for the residency selection committee. While not a practice at all residency programs, it is not uncommon for applications to be screened on factors such as USMLE Step 1 scores, geographic biases, or international medical graduate and reapplicant statuses. One survey study of otolaryngology departmental chairs, program directors, associate program directors, and faculty reported that 31.1% of respondents endorsed use of a numeric USMLE Step 1 score screening process at their institution with an average cutoff of 230.5 ± 8.8. If such screening practices are in place, it would be beneficial for programs to advertise this number to prospective applicants, who may be inadvertently wasting limited time and financial resources to apply to programs at which they will be screened out of further consideration. Even with the transition to a pass/fail Step 1, it is likely that another scored metric, such as Step 2, will continue to be used for this purpose.

Finally, except for 1 institution, no programs provided data for interviewed or matched applicants. While some matched resident data may be obtained through the National Resident Matching Program’s Charting Outcomes in the Match, this information is not separated by individual otolaryngology residency programs. Moreover, resources such as the Texas Star Dashboard require institutional enrollment. Providing matched resident data on individual otolaryngology websites improves accessibility, promotes transparency, and allows applicants to assess their competitiveness at different programs in line with recommendations from the AAMC. In turn, this change may enable students and their faculty advisors to make more informed decisions, by strategically targeting residency programs and thereby reducing the number of potentially unnecessary applications. Future prospective work would be valuable to determine whether providing such information influences the application rates to individual programs.

Our study is limited in that we restricted our analysis to the top 50 otolaryngology residency programs as defined by reputation on Doximity Residency Navigator. We chose to use this resource as it is a tool used by many prospective applicants. Previous research suggests that otolaryngology websites for “large” programs (≥3 residents per year) are more comprehensive than those for small programs. As our list includes mostly large programs, it is therefore unlikely that smaller programs not in this study would contain more robust information than that observed here.

Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrate that otolaryngology department websites contain limited information pertaining to the residency application process for prospective applicants, such as requirements, screening and/or selection, and average interviewee or matched resident statistics. This lack of transparency may make it difficult for candidates to discern their competitiveness at programs and potentially contribute to match inefficiency.

Author Contributions

Nicole M. Mott, design, conduct, analysis, writing, approval and responsibility; Bhavna A. Guduguntla, conduct, analysis, revising writing, approval and responsibility; Lauren A. Bohm, design, revising writing, approval and responsibility, oversight

Disclosures

Competing interests: None.

Sponsorships: None.

Funding source: None.

ORCID iD

Nicole M. Mott

https://orcid.org/0000‐0003‐4834‐3400

References

- 1. Association of American Medical Colleges . ERAS statistics. Published 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/data‐reports/interactive‐data/eras‐statistics‐data

- 2. Association of American Medical Colleges . Apply smart: data to consider when applying to residency. Published 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://students‐residents.aamc.org/apply‐smart‐residency/apply‐smart‐data‐consider‐when‐applying‐residency

- 3. Weissbart SJ, Kim SJ, Feinn RS, Stock JA. Relationship between the number of residency applications and the yearly match rate: time to start thinking about an application limit? J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(1):81–85. doi:10.4300/JGME‐D‐14‐00270.1

- 4. Kaplan AB, Riedy KN, Grundfast KM. Increasing competitiveness for an otolaryngology residency: where we are and concerns about the future. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;153(5):699–701. doi:10.1177/0194599815593734

- 5. Association of American Medical Colleges . Report urges major reforms in the transition to residency. Published August 26, 2021. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.aamc.org/news‐insights/report‐urges‐major‐reforms‐transition‐residency

- 6. Svider PF, Gupta A, Johnson AP, et al. Evaluation of otolaryngology residency program websites. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2014;140(10):956–960. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2014.1714

- 7. Tang OY, Ruddell JH, Hilliard RW, Schiffman FJ, Daniels AH. Improving the online presence of residency programs to ameliorate COVID‐19’s impact on residency applications. Postgrad Med. 2021;133(4):404–408. doi:10.1080/00325481.2021.1874195

- 8. Gaeta TJ, Birkhahn RH, Lamont D, Banga N, Bove JJ. Aspects of residency programs’ web sites important to student applicants. Acad Emerg Med. 2005;12(1):89–92. doi:10.1197/j.aem.2004.08.047

- 9. DePietro DM, Kiefer RM, Redmond JW, Hoffmann JC, Trerotola SO, Nadolski GJ. The 2017 integrated IR residency match: results of a national survey of applicants and program directors. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2018;29(1):114–124. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2017.09.009

- 10. Doximity . Residency Navigator. Published 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.doximity.com/residency/programs?specialtyKey=4667266b‐9685‐49c5‐8a72‐33940db2c9d6‐otolaryngology&sortByKey=reputation&trainingEnvironmentKey=all&intendedFellowshipKey=

- 11. Goshtasbi K, Abouzari M, Tjoa T, Malekzadeh S, Bhandarkar ND. The effects of pass/fail USMLE Step 1 scoring on the otolaryngology residency application process. Laryngoscope. 2021;131(3):E738–E743. doi:10.1002/lary.29072

- 12. National Residency Match Program . Main residency match data and reports. Published 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.nrmp.org/main‐residency‐match‐data/

- 13. UT Southwestern Medical Center . Texas STAR. Published 2021. Accessed July 3, 2021. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical‐school/about‐the‐school/student‐affairs/texas‐star.html