In general, exercise promotes physical and mental health [], but in patients with eating disorders (EDs), unhealthy forms of exercise are common [], comprising features such as exercising according to rigid rules and continuing to exercise despite negative consequences []. Previous studies have used cross-sectional and retrospective designs to identify the regulation of negative emotions as well as the modification of weight and shape as the most important functions of exercise in ED patients []. However, knowledge is lacking about the relationships of mood and ED-related cognitions to exercise in ED patients’ everyday life and about how these associations unfold across time; both are critical prerequisites for researchers and clinicians to develop tailored treatments and are issues which can only be tackled by intensive longitudinal studies [, ].

Here we profited from digital progress and used ambulatory assessment to evaluate exercise activities, mood (valence, tense arousal, and energetic arousal), and ED-related cognitions (drive for thinness [DT] and body dissatisfaction [BD]) in everyday life. We investigated within-subject processes in ED patients compared to healthy controls (HCs). Twenty-nine ED outpatients (bulimia nervosa: 51.7%; anorexia nervosa: 38.0%; other specified feeding or eating disorder: 10.3%) and 35 HCs repeatedly reported on mood and ED-related cognitions in real time in electronic diaries and wore accelerometers for 7 days as they went about their daily routines.

To maximize the within-subject variance of interest, we applied a unique mixed sampling strategy encompassing time-based, event-based, and activity-triggered prompts []. The data were analyzed using multilevel modeling (MLM). The patient characteristics revealed that across all real-life assessments, ED patients on average reported significantly lower mood (valence) and energetic arousal but higher tense arousal, DT, and BD than HCs (all p ≤ 0.001). Moreover, across our combined sample (ED patients plus HCs), mood and ED-related cognitions were significantly altered at the time of e-diary rating directly prior to exercise sessions (all p ≤ 0.05) and directly after exercise (all p ≤ 0.05) when compared to all other assessments (for details on hypotheses, methods, results, and discussion, see the online Supplementary Material; see http://www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000504061 for all online suppl. material).

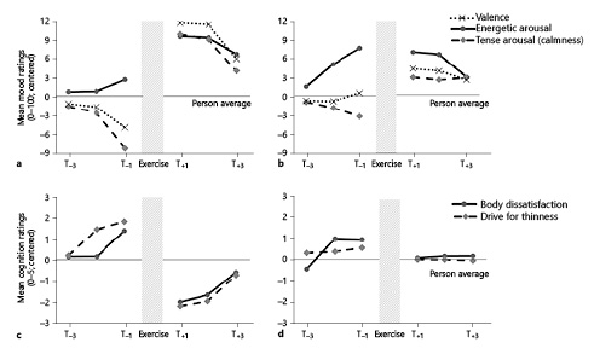

With regard to antecedents, we hypothesized that ED patients in comparison to HCs feel tenser and less well and report both a higher DT and more BD at the time point of exercise initiation compared to the person average (MLM cross-level interaction analyses). The interactions were significant for valence (p = 0.009) and energetic arousal (p = 0.002) but not for tense arousal (calmness), DT, and BD. Accordingly, valence at exercise initiation (T–1; Fig. 1a) in the ED group was lower than valence at exercise initiation (T–1; Fig. 1b) in the HC group (both in relation to their person average; zero line in Fig. 1a, b). In addition, we descriptively inspected and statistically tested the time course of mood and cognitions across multiple time frames prior to exercise (T–3 to T–1 in Fig. 1a vs. b and Fig. 1c vs. d) in ED patients versus HCs. The ED patients showed a systematic decrease in valence prior to exercise, which was not the case in HCs. This leads to the conclusion that a high level of negative mood constitutes a specific antecedent of exercise in ED patients, while energetic arousal does not predict exercise in contrast to the HC group (as confirmed by MLM subgroup analysis).

Fig. 1

a, b Mood prior to and after exercise. Dots depict the descriptive time course of mood changes and show mean values of within-subject centered mood values (valence, energetic arousal, and calmness) measured on visual analogue scales (range: 0–100) averaged across all ratings of the eating disorder (ED) patients (a) and healthy control group (b) for each of the three e-diary assessments prior to exercise (T–1, indicating exercise initiation, to T–3) and after exercise (T+1, indicating exercise completion, to T+3). c, d ED-related cognitions prior to and after exercise. Dots depict the descriptive time course of ED-related cognitions and show mean values of within-subject centered ED-related cognitions (drive for thinness and body dissatisfaction) measured on visual analogue scales (range: 1–5) averaged across all ratings of the ED patients (c) and healthy control group (d) for each of the three e-diary assessments prior to exercise (T–1 to T–3) and after exercise (T+1 to T+3).

Regarding consequences, we hypothesized that ED patients would show higher emotional and cognitive benefits at exercise completion than HCs in all target variables. Indeed, the ED patients felt less tense and better after exercise (see calmness and valence at T+1 in Fig. 1a vs. b) and experienced a lower DT and lower BD (both Fig. 1c vs. d) than the HCs and their person average (zero line in Fig. 1; all pMLM cross-level interactions ≤ 0.05). However, there were no differences in energetic arousal. The descriptive time course of effects subsequent to exercise (T+1 to T+3) depicts that the ED patients’ above-average mood scores (Fig. 1a) and below-average ED cognitions (Fig. 1c) at exercise completion (T+1) regressed to the subjects’ means (zero lines) across time (T+2 and T+3), while the HCs showed the same pattern for mood changes (Fig. 1b) but no change in ED cognitions after exercise completion (Fig. 1d; T+1 to T+3). These observations were largely confirmed by our MLM statistics.

In sum, our results point towards positive changes in mood (calmness and valence) and cognitions (BD and DT) as specific within-person consequences of exercise in ED. The strength of effects largely matches or exceeds those of previous ambulatory assessment studies [] (regarding consequences); to the best of our knowledge, our results on antecedents are the first ones reported.

Our study provides novel insights into mood and cognitions as antecedents and consequences of exercise and how they unfold across time in ED patients’ everyday life. It significantly extends an extensive body of cross-sectional investigations on emotion dysregulation in ED [, , ] by providing ecologically valid findings from the within-subject perspective, evidencing that exercise plays a role in mood and affect regulation: ED patients seem to use exercising as one strategy to regulate adverse mood states (as well as ED-related cognitions) and to compensate for a lack of adequate coping strategies. These positive but short-term effects of exercise might reinforce exercise behavior and increase the risk of unhealthy exercising. However, in turn, our findings of an enhanced benefit from exercise in ED patients also strongly support the use of supervised and tailored exercise in the treatment of ED. We shed light on the time course of mood and dysfunctional cognitions in relation to exercise, which opens promising avenues for novel treatments that include a focus on exercise behavior, exercise-related motives, and the use of supervised exercise itself. For example, real-life data might be used for the detection of critical everyday-life situations as well as for tailored interventions for patients with ED.

Limitations of this study include a relatively small sample size, a limited sampling frequency, a solely female sample, the pending validation of the e-diary questionnaires used to assess ED-related cognitions, and the observational character of the study, precluding causal statements.

Statement of Ethics

The study was approved by the Freiburg University Ethics Committee (No. 65/13). All participants provided written informed consent.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Funding Sources

The study was funded by the Schweizer Anorexia Nervosa Stiftung (No. 37-14).

References

- 1. Morgan AJ, Parker AG, Alvarez-Jimenez M, Jorm AF. Exercise and mental health: an exercise and sport science Australia commissioned review. J Exerc Physiol Online. 2013;16:64–73.1097-9751

- 2. Shroff H, Reba L, Thornton LM, Tozzi F, Klump KL, Berrettini WH, et al Features associated with excessive exercise in women with eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(6):454–61. 0276-3478

- 3. Mond JM, Hay PJ, Rodgers B, Owen C. An update on the definition of “excessive exercise” in eating disorders research. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(2):147–53. 0276-3478

- 4. Meyer C, Taranis L, Goodwin H, Haycraft E. Compulsive exercise and eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2011;19(3):174–89. 1072-4133

- 5. Trull TJ, Ebner-Priemer U. Ambulatory assessment. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2013;9(1):151–76. 1548-5943

- 6. Zawadzki MJ, Smyth JM, Sliwinski MJ, Ruiz JM, Gerin W. Revisiting the lack of association between affect and physiology: contrasting between-person and within-person analyses. Health Psychol. 2017;36(8):811–8. 0278-6133

- 7. Reichert M, Tost H, Reinhard I, Schlotz W, Zipf A, Salize HJ, et al Exercise versus Nonexercise Activity: E-diaries Unravel Distinct Effects on Mood. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2017;49(4):763–73. 0195-9131

- 8. Killingsworth MA, Gilbert DT. A wandering mind is an unhappy mind. Science. 2010;330(6006):932. 0036-8075

- 9. Lavender JM, Wonderlich SA, Engel SG, Gordon KH, Kaye WH, Mitchell JE. Dimensions of emotion dysregulation in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: A conceptual review of the empirical literature. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;40:111–22. 0272-7358

- 10. Treasure J, Schmidt U. The cognitive-interpersonal maintenance model of anorexia nervosa revisited: a summary of the evidence for cognitive, socio-emotional and interpersonal predisposing and perpetuating factors. J Eat Disord. 2013;1(1):13. 2050-2974

M. Reichert and S. Schlegel contributed equally to this work.