For centuries, European countries have colonized, invaded, occupied, and exploited more than half of the world. Today, after most colonized countries have gained independence, many European countries are experiencing immigration flows from these same countries (). These post-colonial migration flows (e.g., Brazilian immigrants to Portugal, Colombians to Spain) possess specific characteristics, most notably that immigrants often speak the same language as their receiving countries, with whom they share a sense of “entangled history” rooted in complex colonial legacies (). The present study examines how subtle forms of discrimination—or microaggressions—are experienced by foreign-born immigrant women in Portugal, one of the longest-lived colonial empires in European history.

In former colonizing nations, such as Portugal, the post-colonial belief systems and ideologies about the superiority of colonizers over the colonized perpetuate patterns of oppression and discrimination by justifying, sustaining and reinforcing power asymmetries between immigrants and natives (). While the atrocities of past colonial acts are often minimized through historical negation (), contemporary egalitarian beliefs and anti-prejudice norms lead to more subtle, ambiguous, and socially normalized forms of discrimination ().

The microaggressions framework (; ) provides a valuable theoretical approach for examining subtle forms of perceived discrimination. Defined as covert and ambiguous slights, insults, and invalidations, microaggressions communicate negative messages to individuals based on their membership in socially devalued or marginalized groups (). This framework has become widely adopted in the social sciences, particularly psychology, and has been examined using both quantitative and qualitative methodologies. Quantitative studies have established associations between microaggressions and psychological outcomes such as depression, anxiety, and stress (). Qualitative studies have explored how different populations perceive and interpret microaggressions, leading to the development of thematic taxonomies for various groups, including ethnic and racial minorities (), women (), and multiply marginalized groups such as Black women (). Nevertheless, the microaggressions framework has primarily been studied in the U.S.-American context (; ; ) and remains a very Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic (W.E.I.R.D.) framework, whose generalizability is often taken for granted.

Despite the relevance of subtle forms of discrimination in the relations between immigrant groups and their receiving societies, no studies have attempted to examine the manifestation of microaggressions at the intersection of immigrant status and gender by considering the experiences of foreign-born immigrant women. Representing roughly 50% of the global migrant population, immigrant women face significant disadvantages in social status and resources compared to their male counterparts (). For instance, they are less likely to participate in the labor force, are more exposed to informal work, and face greater economic vulnerabilities. They often encounter unequal access to migration rights and resources, hindering their integration into receiving countries (). A recent review also found that immigrant women report higher prevalence of common mental health concerns than immigrant men (). Hence, scholars emphasize the importance of viewing migration as a gendered phenomenon shaped by intersecting racist, sexist, and xenophobic systems (), of which microaggressions are subtle, yet significant manifestation. Given these gaps and the limited research outside the United States, this study adopted a post-colonial feminist and intersectional lens to examine the microaggressions faced by foreign-born immigrant women in Portugal.

Microaggressions and Intersectionality

Originally proposed by , the construct of microaggressions was later expanded by to examine the manifestation of multiple forms of subtle discrimination directed at individuals because of their belonging to socially devalued or marginalized groups. Microaggressions have been widely conceptualized as covert, indirect, ambiguous, and ambivalent expressions of prejudice that are ubiquitous in everyday intergroup interactions (; ; ). These subtle forms of discrimination can be seen as micro-interactions that operate by disrespecting, devaluing, invalidating, overlooking, pathologizing, excluding, exoticizing and “othering” the target (; ; ; ).

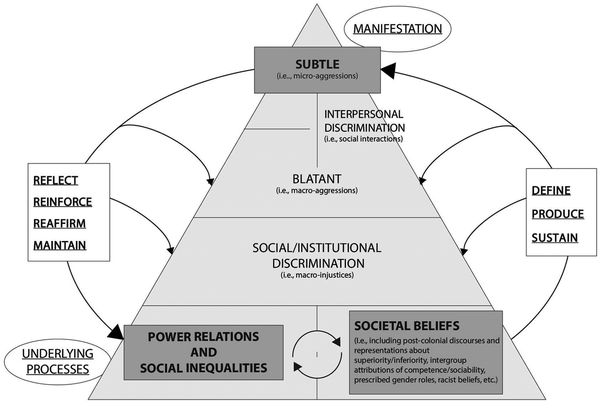

As shown in Figure 1, “microlevel” manifestations of subtle discrimination (top of the pyramid) emerge from a macro-societal context in which there is a systemic structure of power and prejudice (; ; ), rooted in social hierarchies and often motivated by worldviews reflecting status disparities, legitimizing myths, pathological stereotypes, and supremacy ideologies (bottom of the pyramid; ; ; ). The social inequalities inherent to these systems are reproduced at the societal and institutional level, through macro-injustices (), as well as at the interpersonal level, manifesting along a continuum that ranges from blatant discriminatory instances (i.e., macroaggressions) to subtle ones (i.e., microaggressions) (; ). Because of their chronic, socially unsanctioned, and normalized nature, microaggressions are difficult to identify, quantify, and address by targets, whose experiences are often unacknowledged or dismissed as “exaggerated” or “paranoid” (; ). As such, microaggressions ultimately operate as constant, insidious reminders of minorities’ underprivileged positions in social hierarchies by perpetuating and reinforcing stereotypes, expectations, and social roles (; ).

Figure 1

A multilevel process model for the manifestation of subtle, blatant, and institutional discrimination.

Note. This figure was developed upon relevant literature highlighting the importance of framing microaggressions in the broader context of structural inequalities, rather than just as subtle social stressors (e.g., ; ; ; ; ). The pyramid serves as a visual representation of social systems of power and injustice, in which structural inequalities—rooted in and reinforced by societal beliefs of supremacy and subordination—(bottom) and their manifestation at the institutional (middle) and interpersonal level (top) coalesce to produce, sustain, and reinforce the privilege of certain groups alongside the oppression of others. Microaggressions represent the subtlest and most ambiguous expression of these complex systems, thus also being the most difficult to challenge and address. As a result, they function as invisible—but still powerful—instruments for maintaining the existing status quo.

Scholars have adopted qualitative methodologies to produce thematically organized taxonomies (; ), describing how microaggressions manifest, are perceived, and conveyed through hidden messages bound within socially shared beliefs and representations in intergroup relations (Figure 1). For example, the taxonomy of gender microaggressions (i.e., focused on women's experiences; ; ) includes themes such as “sexual objectification” (i.e., being treated as a sexual object) and “assumptions of inferiority” (i.e., being assumed to be less competent than a man).

Examining microaggressions towards racial minority immigrants in the United States, identified themes such as “second-class citizenship” (e.g., being ignored or made to feel invisible) and “ascription of intelligence and language-related microaggressions” (e.g., being assumed to be less intelligent due to foreign accent). This taxonomy examines the shared experiences of both U.S.-born racialized individuals and foreign-born immigrants; yet, it also suggests that there are some important differences between them. For instance, preliminary evidence shows that foreign-born immigrants are more likely to be seen or treated as inferior than U.S.-born immigrants (). Given that their experiences of microaggressions are quantitatively and qualitatively different, these two groups should be investigated separately.

In recent years, scholars have adopted intersectionality approaches () to examine how the interplay between multiple systems of power and oppression contributes to the manifestation of microaggressions for individuals from multiple socially marginalized groups (). Among these approaches, intracategorical intersectionality () examines groups situated at the intersection of multiple social categories, allowing for an in-depth understanding of their multifaced lived experiences, uniquely shaped by interlocking forms of inequality (). For instance, the taxonomy of Gendered Racial Microaggressions directed at Black women and girls includes themes such as “standards/assumptions of beauty and objectification” (i.e., assumptions of aesthetics, devaluation of physical features, and hair exoticism; ; ). These microaggressions were found to partially overlap with those experienced by Black men (e.g., assumptions of criminality, ) and White women (e.g., invisibility, ), but also to include unique aspects specific to the U.S.-American social representations about Black women (e.g., “the Jezebel stereotype”, ). Considering the different cultural contexts, migration patterns, and historical beliefs, the taxonomies developed for U.S.-born racialized women may not apply to foreign-born immigrant women living in European post-colonial societies. Here, post-colonial feminist critical approaches provide the context-specific considerations essential to understand the nuanced experiences of multiply marginalized groups at the intersection of gender, ethnicity, and immigrant status.

A Post-Colonial Feminist Approach to Microaggressions

The theory of colonial discourse is a post-colonial critical approach focused on examining and challenging the systems of knowledge and beliefs derived from the colonization process, as well as on uncovering their social and historical roots and the role they play in shaping social identities and discourses among both formerly colonizing and colonized nations (; ). In European countries, collective remembrance and social representations are imbued with views about the centrality and superiority of Europe, and still serve as a primary tool to maintain colonial power and preserve social hierarchies, as well as to justify (or deny) the injustices of the past and the violence against and exploitation of inferior “others” ().

A core component of colonial discourses is stereotypes, which possess an ambivalent nature and are based on a dichotomous, antithetical, and hierarchical representation of the colonizers versus the colonized (; ). For example, whenever European colonizers were represented as civilized, rational, and morally superior, colonized people were represented as primitive, irrational, and degenerate (; ; ). Although they have been transformed and challenged over time, these representations remain central to contemporary post-colonial cultural heritages ().

(Post-)colonial theory has been integrated with intersectional and feminist approaches () to critically question the forms of oppression and subordination taking place when colonial dominance and patriarchy become intertwined (). Within colonizing nations, post-colonial feminist theory represents a powerful tool to identify and dissect social structures of power and inequality (i.e., bottom of the pyramid in Figure 1), as well as the underlying content of their manifestations, including microaggressions (i.e., top of the pyramid). Given its W.E.I.R.D. and U.S.-centered focus, the microaggressions research framework may especially benefit from the conceptual and analytical tools offered by this approach. Yet, to date, very few studies have examined microaggressions through post-colonial lenses (e.g., ), and the integration with intersectional feminist perspectives remains scarce. Therefore, post-colonial feminist discourse theory offers a new set of lenses to conduct an in-depth examination of complex and multifaceted systems of power and inequality, as well as of the social narratives and representations underlying microaggressions towards immigrant women in European settings, like the Portuguese one.

The Portuguese Context

Portugal's colonial history dates to the maritime expansion of the Portuguese kingdom in the first decades of 1400 and is characterized by historical events such as the colonization of Brazil in 1500 and the domination of several African countries, as well as by a deep involvement in the slave trade market (). In 1822, Brazil was the first country to proclaim its independence, while the African countries only attained it in the 1970s ().

A distinctive ideological discourse about the Portuguese colonial relations emerged in the early 1960s as a legitimizing rationale for Portugal's prolonged colonial domination of 500 years (). Confronted with an increasing global condemnation for persisting in colonial exploitation during the post-World War II era, the authoritarian Portuguese regime (which governed Portugal from 1924 to 1974) aimed to portray Portuguese colonialism in a positive light, presenting it as benevolent and tolerant, as opposed to other colonizing European nations such as Spain or the United Kingdom. This idea took form through a term coined luso-tropicalism, which depicted the Portuguese (i.e., Luso) as having a culturally hybrid identity that equipped them to adapt to the tropics (i.e., Tropicalism) during colonization by establishing harmonious relations with colonized groups and engaging in miscegenation (; ; ). After the independence of the colonies, these social representations of the colonial past continued to be culturally shared. Today, these representations manifest themselves in a set of post-colonial beliefs related to: (a) the existence of harmonious relations of the Portuguese with formerly colonized countries, resulting from a benevolent and pacific colonial past; (b) the ability to culturally integrate immigrants from formerly colonized countries in the contemporary Portuguese society, (c) the belief that, due to their culturally hybrid identity, the Portuguese are less prejudiced towards immigrants than the natives of other European countries ().

Immigrants in Portugal

In 2022, immigrants represented 7.5% of the resident population in Portugal (; ). Almost half (44%) of these immigrants come from the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), a group of Portugal's former colonies that today maintain Portuguese as the official language: Brazil, Angola, Cape Verde, Mozambique, Guinea Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, East Timor, and St. Tomé and Principe (). The largest share of CPLP immigrants comes from Brazil, representing 31% of the total immigrant population (). Among immigrants from these countries, the share of women is often larger than the share of men (e.g., representing 54% of the Brazilian and 56% of the Angolan immigrant population). Yet, they are paid less than immigrant men and Portuguese natives and represent the largest share of unemployed immigrants in Portugal ().

The linguistic similarity between immigrants and Portuguese natives may represent an especially relevant factor in the study of microaggressions. While many immigrants who move to the U.S. may not speak English fluently enough to understand the indirect messages or secondary meanings encoded into apparently innocuous communications (; ), immigrants moving to Portugal from former colonized countries typically speak Portuguese as their native language, which should enable them to detect microaggressions in interactions with Portuguese natives.

To date, only one study () has examined the experiences of microaggressions of Black immigrants (both men and women) from Portuguese speaking African countries in Portugal, identifying five major themes: (a) unwelcoming stance towards immigrants, (b) belief in the inferiority of immigrants, (c) assumption of dangerousness, (d) denial of personal differences, and (e) exoticization of aspects of the cultures. Yet, this study did not provide in-depth insights into the colonialist beliefs that shape microaggressions in the Portuguese context and it also overlooked the gendered side of immigrant women's experiences, where the interlocking dynamics of multiple systems of oppression such as racism, sexism, and colonialism can be observed (). Other scholars have studied the discrimination experiences of immigrant women in Portugal (especially those from Brazil) and sometimes also considered the role of colonialism (e.g., ; ); however, to the best of our knowledge, the microaggressions’ framework has not been applied to this population.

The Present Study

Since Sue et al.’s () seminal work on racial microaggressions, this framework has expanded to encompass various underprivileged groups, including women and ethnic minorities (e.g., ; ). Additionally, recent studies have adopted intersectionality approaches to explore the experiences of individuals belonging to multiply marginalized groups, such as Black women (). However, although foreign-born immigrants have sometimes been examined as a homogeneous group (; ), the unique experiences of foreign-born immigrant women have been completely overlooked. Moreover, relatively less attention has been put on how sociohistorical factors shape microaggressions, particularly in post-colonial societies. To address these gaps, the present study adopted an intracategorical intersectional approach (; ) to examine the experiences of foreign-born immigrant women from the CPLP in Portugal in focus group discussions.

Drawing upon the existing taxonomies of microaggressions (e.g., ) and post-colonial feminist discourse theories (e.g., ), we proposed an integrated taxonomy of Gendered Colonialist Microaggressions to examine the manifestation of microaggressions (i.e., top of the pyramid in Figure 1) and shed a light on the social discourses, beliefs, and representations underlying these subtle forms of discrimination (i.e., bottom of the pyramid). Given that power asymmetries and inequalities manifest themselves in common ways (e.g., inferiority) as well as in context-specific manners shaped by unique social and cultural beliefs, two primary research questions guided our inquiry:

What microaggressive messages are conveyed to immigrant women from the CPLP, and to what extent do they align with existing taxonomies on racial, gendered, and gendered racial microaggressions? Additionally, which microaggressive messages emerge as new or unique to this population?

How can these microaggressive messages be contextualized within the broader colonialist, sexist, and racist structures of power and inequality?

Method

Participants

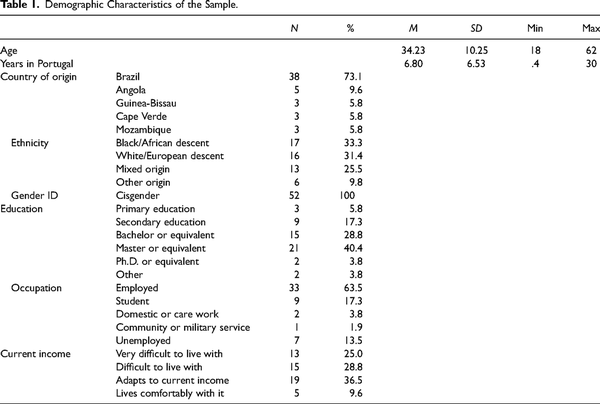

Fifty-two foreign-born immigrant women from the CPLP participated in a total of 10 focus groups with three to six participants each. Participants’ age ranged from 18 to 62 years (Mage= 34.2, SD = 10.3). Thirty-eight were born in Brazil, five in Angola, three in Guinea-Bissau, three in Cape Verde, and three in Mozambique. Brazilians also represent the largest group of immigrants from the CPLP (69%; ). The sample ethnicity was well balanced with 33.3% of them self-identifying as Black or of African descendent, 31.4% as White or of European descent, 25.5% as of mixed origins, and 9.8% as of other origin. Most participants held a master's degree (n = 21) or a bachelor's degree (n = 15) and reported to be employed (n = 33) or a student (n = 9) (for a complete overview of sociodemographic characteristics, see Table 1). Participants’ length of residence in Portugal ranged from 5 months to 30 years (M = 6.8 years, SD = 6.53). On average, during the focus groups each participant reported six incidents identifiable as microaggressions (SD = 3.7, range= 1–18; see Procedure section for more details). The number of incidents reported was positively correlated with participants’ length of residence (r = .469, p < .001), while there were no significant relations for ethnicity.

Procedure

Participant Selection

Participants eligible for the study were foreign-born adult immigrant women (age > 18) from the CPLP countries (Brazil, Angola, Mozambique, Cape Verde, Guinea-Bissau, Equatorial Guinea, São Tomé and Principe, Timor-Leste) residing in Portugal for more than 3 months (i.e., the typical duration of a tourist visa, which helped screen for individuals likely intending to settle and have contact with the local population). Recruitment was based on convenience and snowball sampling methods, employing virtual flyers distributed on social media platforms and the University System of Participation in Psychological Research (SPI). Following completion of a screening survey providing demographic details (e.g., gender, age, country of birth, duration of residence in Portugal, ethnicity), eligible participants were contacted to schedule their participation in a focus group. To compensate participation, each participant received a five-euro voucher. Focus group composition took into account participants’ country of origin and ethnicity to enhance data quality, as recommended by .

Data Collection

A semi-structured interview guide was developed following established guidelines for focus group facilitation (; ) and drawing on prior qualitative research on microaggressions (; ; ). Additionally, we employed the Critical Incident Interview Technique (CIT; ), designed to elicit significant memories (i.e., incidents) shaping participants’ perceptions of reality. Previous studies have utilized the CIT to explore microaggression experiences (e.g., ). Prior to data collection, a pilot focus group was conducted to refine the interview format and guide. Participants’ feedback led to revisions, including rephrasing unclear sentences, adding follow-up questions to enhance discussion, and removing less relevant questions for better time management.

Focus groups were held between February and March 2022. All sessions were conducted in Portuguese, online via Zoom due to post-pandemic circumstances, lasting approximately 90 minutes each. Participants were given specific instructions for joining the online sessions. To promote active engagement, they were required to have a functioning camera (which should remain on throughout the session) and microphone, a stable Internet connection, and to log in five minutes early to address any potential technical issues. To protect everyone's privacy and foster a safe discussion space, they were also asked to join from a quiet, private location and ensure that no one else could overhear the session. They were encouraged to speak freely, one at the time, by unmuting their microphones.

Participants provided informed consent before each focus group. Then, they were briefed on the concept of microaggressions and presented with a series of adapted scenarios encompassing racial, gender, and gendered racial microaggressions (; ; ; ; ; ; ). These scenarios included assumptions of inferiority, second-class citizenship, microinvalidations, exotization, environmental microaggressions, work and school microaggressions, beauty stereotypes, sexual objectification, and assertive immigrant women stereotypes (these labels were only used internally by the research team to structure the interview guide and were never disclosed to participants). Due to time constraints, four scenarios were presented in each focus group (each time in a different order), in such a way that all scenarios were discussed at least in three different focus groups. This approach allowed to explore a large range of microaggression experiences while at the same time engaging in a deep and exhaustive discussion within each group.

Participants were asked if they had encountered similar incidents as immigrant women in Portugal. Indeed, intracategorical intersectional approaches do not require that respondents disentangle their experience into separate identities; instead, “they may report that their mistreatment is due to their unique blended identity” (, p. 959). For example, participants were presented with a scenario on assumptions of inferiority: “A Portuguese person treated you as inferior because you are an immigrant woman. For example, they assumed that you had an inferior education, they assumed that you were poor, they assumed that you were less intelligent, or they assumed that you had a low-paying job.” These examples were employed as a stimulus material (); that is, to ensure that all participants had a similar understanding of microaggressions, facilitate the remembrance of specific incidents, and provide grounds for a deeper group discussion. For each situation, participants were asked if they had ever experienced something similar or witnessed it happening to another immigrant woman, and were invited to share any microaggressions they remembered, even if it was not related to the examples described by the interviewer. Whenever a participant shared a new incident, the interviewer also asked the other focus group members whether they shared similar experiences.

At the conclusion of each session, participants received a list of organizations offering support to immigrant women facing discrimination. Focus groups were video recorded and transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were anonymized, with participants’ names replaced by identifiers. Excerpts included in the results section underwent translation into English using a committee-based approach. Two researchers independently translated the original excerpts in parallel, after which consensus was reached via collaborative review with the support of a third researcher ().

Coding and Data Analysis

We conducted thematic analysis (TA; ), which provides a diverse, flexible set of approaches to capture patterns of latent meaning in microaggressions and contextualize them within broader power structures. Our analysis comprised a double approach to TA—codebook TA and reflexive TA (, )—carried out in two steps, each addressing one of our primary research questions. The combination of different approaches is permitted by the flexible nature of TA, as long as a coherent rationale for the choice of such combination is provided ().

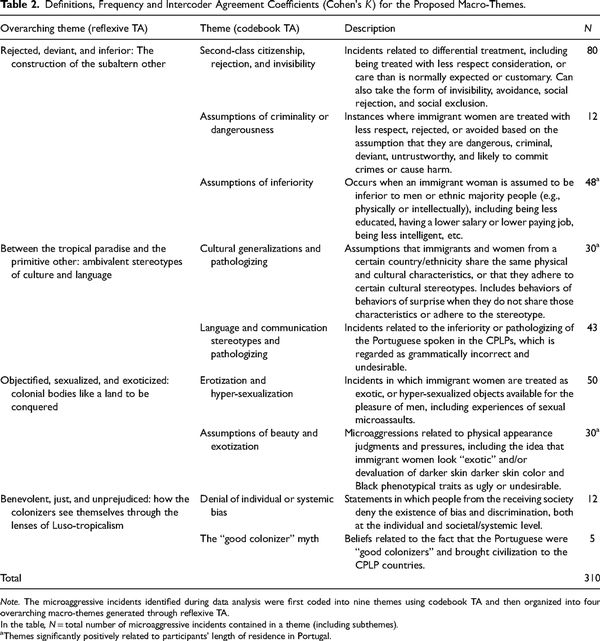

Prior to data analysis, we defined the coding unit as any significant data describing a single microaggressive incident in an interpersonal interaction. The first author conducted the coding procedures by identifying and highlighting relevant data segments in each transcribed document (). Subsequently, the data were imported and analyzed using NVivo. A total of 310 microaggressive incidents were identified as relevant for data analysis.

Step One: Codebook TA

It was deemed that the most appropriate approach to answer our first research question (i.e., what microaggressive messages are directed at immigrant women, and how do they fit with or diverge from the existing taxonomies of microaggressions?) was deductive-inductive codebook TA (, ). Codebook TA techniques seek a hierarchical, structured approach to the data, in which a coding scheme is used to chart the developing analysis while also recognizing the importance of reflexivity and subjectivity. This approach is deemed especially useful when conducting the analysis in teams and working with large sets of data, and is theoretically suitable to identify broad patterns of meaning and discourse ().

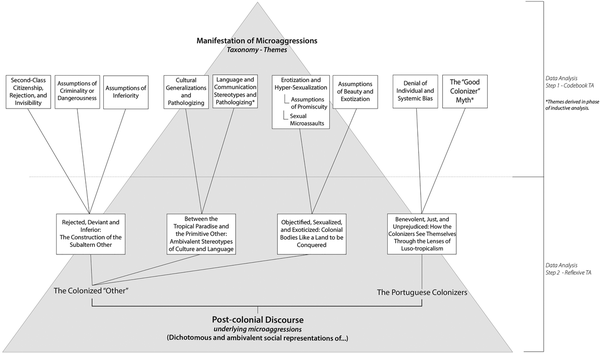

Initial themes were deductively generated through an a-priori coding scheme, developed by drawing upon relevant microaggressions taxonomies and multiple rounds of discussion and revision within the research team. Then, an inductive TA approach was employed to analyze the pieces of data which did not fit the a-priori coding scheme. The analysis involved an iterative process in which themes were collaboratively developed and revised multiple times. The result of this deductive-inductive process was a final coding scheme containing seven themes and two sub-themes derived deductively, and two themes derived inductively (top of the pyramid in Figure 2; see Table 2 for a detailed overview).

Figure 2

Conceptual map of the identified themes (top of the pyramid) and their links with post-colonial discourse (bottom of the pyramid).

Step Two: Reflexive TA

Given the need for a more critical and constructivist approach to the data to answer our second research question (i.e., how can microaggressive messages be contextualized within the broader colonialist, sexist, and racist structures of power and inequality?), we conducted reflexive TA. Compared to codebook TA approaches that focus on shared topics conveying a similar idea across data, reflexive TA draws together patterns of meaning that on the surface can appear disparate. Therefore, reflexive TA was conducted to produce an in-depth analysis of the themes generated in step one (codebook TA), to develop overarching macro-themes () informed by post-colonial feminist discourse theory. This phase was organically centered around researchers’ individual interpretation and reflection, followed by group discussions among all three authors, resulting in four macro-themes. Themes were subsequently revised, defined, and named, and are presented below (bottom of the pyramid in Figure 2).

Methodological Integrity, Openness and Transparency

The present study was approved by the university's Ethics Committee (N° 03/2022). Various procedures were undertaken to ensure methodological integrity, as described earlier (e.g., video recording, verbatim transcription, thick descriptions). During data analysis, consistency was attained through multiple rounds of discussion among the research team. Consistent with the Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines (), we provide a detailed description of the methods used in the study including our theoretical frameworks of reference and analytical approaches. The study materials, anonymized transcripts, and coding scheme are available upon request to the corresponding author. Given its exploratory nature, the present study was not pre-registered.

Positionality

The research team comprises three cisgender women researchers with a strong intercultural background. Their positionality is informed by an academic background in social and intercultural psychology, multiple work experiences with migration, and prior research on microaggressions. Due to their academic training, the authors’ methodological choices are influenced by postpositivist paradigms. At the same time, the engagement with cultural and (de)colonial psychology provides them with an understanding of knowledge as relative, socially, historically, culturally constituted, and embedded into broader structures of power. This perspective is more closely related to constructivist and post-structuralist epistemologies, which often guide post-colonial theoretical frameworks and TA methodologies. The convergence of these two paradigms is visible in the two-step approach to TA (codebook and reflexive), a “theoretically aware” () combination that accurately reflects their research values and objectives.

The first author, who led data collection and analysis, is a White, Italian doctoral student, living in Portugal since 2017. She had previously lived in Brazil and speaks Brazilian Portuguese at a native level. In Portugal she is often misidentified as a Brazilian, being targeted by the same microaggressions directed at Brazilian women. This particular positionality facilitated her interaction with participants during the focus groups, while also allowing her to gain some distance from the data during analysis. Despite not self-identifying as Brazilian, she empathized with the experiences of immigrant women, which led to some emotional discomfort during the research process. In this context, regular introspective conversations with the second author helped clarify data interpretation and refine the analysis. The second author, who supervised all steps of the research process, is a tenured university professor with a background in cross-cultural psychology, born and raised in Germany, with a Black Brazilian mother and a White German father. Since 2011, she is living and working in Portugal where she is often identified as Brazilian due to her mixed heritage. The third author is a White Portuguese researcher, with a Ph.D. in Migration Studies and currently conducting research on the consequences of luso-tropicalism for the maintenance of social and racial inequalities. Given her expertise, she was especially engaged in the procedures of reflexive TA aimed to contextualize microaggressions within post-colonial feminist discourse theories. The authors acknowledge potential unconscious colonialist biases in their research, and are vigilant and engaged in identifying, challenging, and deconstructing them at all levels of their work.

Results

Immigrant women's experiences of microaggressions were initially coded into nine themes (and two sub-themes) drawing upon previous microaggressions taxonomies. These themes (identified through codebook TA) represented the ways in which microaggressions manifest in the lives of participants and are centered around the messages conveyed through each microaggressive incident (i.e., top of the pyramid in Figure 2). Looking at these themes through the lenses of post-colonial feminist discourse theory, we generated four overarching themes (through reflexive TA; bottom of the pyramid in Figure 2), which were ultimately ascribed to the notion that post-colonial discourses are rooted in ambivalent and dichotomous social representations of the superiority of colonizers versus the inferiority of colonized “others.”

Representations of the Colonized “Other”

Rejected, Deviant, and Inferior: The Construction of the Subaltern Other

Three themes appeared to be directly related to the belief in the subalternity of immigrant women (), who are often ignored and made to feel like they do not belong, assumed to be deviant or inclined to criminality, and paternalistically treated as less competent and intelligent. These themes have been widely discussed in the literature as an important form of microaggression towards different groups (), including women (), racialized individuals (; ), and multiply marginalized groups, such as Black women (). However, within the Portuguese context, they also reflect the cultural and historical specificities characterizing post-colonial, gendered representations of immigrant women as “subaltern” others ().

Second-Class Citizenship, Rejection, and Invisibility

Participants often reported experiences of being “treated with less respect, consideration, or care than is normally expected or customary” (, p. 1000). This theme included incidents characterized by subtle snubs and dismissive behaviors, often accompanied by non-verbal cues such as avoiding eye contact, facial expressions of dislike, or keeping physical distance, which made participants feel they were being avoided, silenced, or marginalized (; ; ; ; ). More often, participants reported being ignored, overlooked, unheard, unseen or made feel invisible:

I am going to the gym […] I get there, I enter, and I say, “Good morning!” to the colleagues who are in the locker room. I had been going there for some time now, but no one ever answers. It was always like that. In that day I said, “Good morning, ladies!”, but no one replied. So, I said again, “Good morning”, to be sure that they heard me. No one replied. Then you know, when the tears are almost coming down and you think “No, I am not going to cry!”. Then a Portuguese woman entered and said, “Good morning, girls!”, and everyone replied “Good morning!” (P41—Brazil, Black, 14 years in Portugal)

Participants interpreted these instances as perpetuating the message of being “less than” Portuguese nationals, of “not belonging” in the community or society. Incidents like this appeared to be highly common in the experiences of our participants, who reported constantly feeling as an outsider, rejected, invisible, or irrelevant. Within the context of post-colonial intergroup relations, these microaggressions ultimately seemed to perpetuate the “othering” process of immigrant women, often using their nationality or foreigner status to justify the occurring differential treatment ().

Assumptions of Criminality or Dangerousness

This theme included instances where immigrant women (especially Black women) were treated with less respect, rejected, or avoided based on the assumption that they are dangerous, criminal, deviant, untrustworthy, and likely to commit crimes or cause harm (; ; ). For example, participants explained that they were often looked at suspiciously, followed around, or asked to show the content of their bags in shopping stores:

I have this thing since I am very young, I do not enter in stores with bags. I always leave my bag at the entrance because they asked me so many times [to look into my bag], that I think “I will not allow them to do this to me”. So, I leave my things at the entrance. And they always follow me around the shop. Once, I was with a friend of mine who entered with a huge bag […]. I entered and the attendant was following me, and in the end she [my friend] said “Look, have you seen the size of my bag?!”, it was a travel bag, “Have you looked at me, have you looked at the size of my bag? She does not have any bag, why are you following her and not me? If I wanted to, I could have stolen a lot of things, but you did not follow me because I am Portuguese”. That was a situation in which even the person who was accompanying me perceived this. (P20—Guinea Bissau, Black, 20 years in Portugal)

Participants also reported not being given responsibilities at work or having someone covertly implying (sometimes even as a joke) that they had stolen something. This theme reflects (post-)colonial discourses on criminality, which ultimately serve to enforce social power and control over the colonized (e.g., by surveilling or following them in a store; ).

Assumptions of Inferiority

This theme referred to assumptions that immigrant women are inferior to men or members of the receiving society and contained instances in which immigrant women were assumed to be less competent, intelligent, or educated, or to possess lower social status, income, or work (; ; ; ; ; ). Different from the previous themes, in which participants reported being treated disrespectfully, ignored, or rejected based on their nationality or skin color, this theme included, for example, the expectation that participants would be living in poor neighborhoods, hold lower paying jobs, or be service workers:

This was around three years ago, I was going out to work, I had become a mother one year or so before, and I met a neighbor and she asked, “Did you find a job?” and she asked how I managed to find a job, then she said, “I am glad that you could find something in the cleaning sector”. And I replied “No, I am an administrative assistant, I have a job in an office”, and she was all surprised that I was working in the administrative system. [P21—Guinea Bissau, Black, 20 years in Portugal]

Participants also described incidents in which others treated them as less competent or intellectually inferior and displayed surprise when they “exceeded” the low expectations held towards them. For example, one participant described receiving excessive compliments after doing a presentation in English: “A Brazilian speaking English!” (P1, Brazilian, Mixed origin, 3 years in Portugal). Within (post-)colonial structures, these microaggressions are sustained by, and at the same time reinforce, the belief that the colonized “others” are inferior and cannot possibly occupy high status positions in society ().

Between the Tropical Paradise and the Primitive Other: Ambivalent Stereotypes of Culture and Language

Colonialist discourses also reflected stereotyping and essentialization processes based on the “myth of the tropics” and on historical representations of colonized people as primitive and savage—in opposition to the modern, developed, and civilized European societies (). These discourses took the shape of microaggressions perpetuating generalizations and pathologizing immigrant women's cultural heritage, as well as their (Portuguese) language or accent and communication styles.

Cultural Generalizations and Pathologizing

This theme included microaggressions generalizing the belief that immigrants and women from a certain country or ethnicity all share the same cultural characteristics and practices, or adhere to specific cultural stereotypes (e.g., “people in Africa sleep on trees and hunt tigers”) (; ; ):

And many times, I have been asked, like… “but from Mozambique, how did you come here… how did you manage to get here? How do you live there? Do you have internet?”. I have heard so many stupid questions […] “In Mozambique, how is it like? What do you eat? Do you also have those people who do not have clothes and walk naked? […] Do you live among the animals? How is it? Have you ever seen a lion? Have you ever killed a lion? Have you ever…” And it may seem unbelievable, but I have never seen a lion. I do not even know how a lion is. (P17—Mozambique, Black, 2 years in PT)

This theme also included behaviors of surprise or hostility when immigrant women showed that they did not adhere to certain stereotypes about their culture or defied the primitivistic portraits of their countries of origin. The microaggressive messages perpetuated in these incidents were sourced in the myth of the tropics, characterized by ambivalent representations of former colonies as “tropical paradises” and “uncivilized lands,” defining, in opposition, the colonizers’ as civilized, advanced, and culturally superior ().

Language and Communication Stereotypes and Pathologizing

As already mentioned above, our sample was composed of immigrant women born in the CPLP, which also represents a large part of Portugal's former colonized territories. All countries in the CPLP have Portuguese as their main and official language, and thus all our participants were native Portuguese speakers. Yet, the Portuguese spoken in each country of the CPLP is characterized by very different and distinct accents, which make people from these countries easily identifiable as immigrants in Portugal. Here, participants’ accent not only made them easily identifiable as foreigners (as previously identified by ), but was also the direct object of discrimination (), communicating the idea that the Portuguese spoken in their countries is grammatically incorrect, inferior, undesirable, unacceptable, or not comprehensible:

I used to work in a marketing department […] And we had this boss that was like, a bit authoritarian, let's say, who looked at us with a certain superiority […] And once, she asked me to do [some work], and she used to say, “This is not how we speak here, this is not the way we speak here”. And there was something like a comma, and I said “Look, I think that this needs a comma here”, and she said, “You don’t need a comma here, these are the differences between the Portuguese and the Brazilian language”. (P2—Brazil, White, 3 years in Portugal)

Participants often reported that their language was labeled as “Brazilian,” “Angolan,” “Mozambican,” instead of “Portuguese” (i.e., an equivalent of this may be saying to someone from Australia that they speak “Australian” rather than “English”). This labeling made them feel as if their language was not regarded as proper Portuguese, since the only “true” Portuguese is spoken in Portugal (). Additionally, they described incidents in which their accent was imitated, caricaturized, made fun of, or in which they were being complimented for “speaking Portuguese very well.” This theme highlights the ambivalent nature of colonial discourses, both benevolent and hostile, where language is simultaneously perceived as an element of similarity and as a “corruptive” threat to the Portuguese culture (). This ambivalence is ultimately solved through the belief in the existence of a “correct” (and therefore, superior) versus “wrong” (inferior) Portuguese language (; ).

Objectified, Sexualized, and Exoticized: Colonial Bodies Like a Land to be Conquered

Although they represent a highly heterogeneous population, immigrant women often share similar discrimination experiences, such as those related to sexual objectification, hyper-sexualization, and exotization. The themes described below represent the clearest intersection between colonialist, sexist, and racist beliefs, depicting immigrant women as colonial bodies, possessing exotic beauty, sexually available (; ; ).

Erotization and Hyper-Sexualization

A largely recurrent theme included microaggressions at the intersection of gender, immigrant status, and/or ethnicity, which were expressed by sexual objectification, erotization, and hyper-sexualization (; ; ). Participants reported microaggressions related to the idea that immigrant women are sexual objects for the pleasure of Portuguese men (; ), or that they have more interest and availability for sex than Portuguese women:

This generation, generation Z, when they go to the club, they pretend that they are Brazilians when they want to make out. They pretend to be Brazilian, imitate the Brazilian accent and, if someone asks, they say that they are Brazilians. I once hanged out with a group of Portuguese women who said that the best compliment that they ever received as women was that they did not twerk like Europeans, that they almost seemed Brazilian because of their butt. (P14—Brazilian, White, 5 years in Portugal)

These representations are rooted in a “porno-tropical” tradition where culture-specific colonialist beliefs such as luso-tropicalism and sexism intersect to create the image of the immigrant woman reduced to an “ownerless land,” a colonizable body awaiting to be conquered and always available for the pleasure of colonizers (; ).

Assumptions of Promiscuity. A particular set of beliefs that portrays immigrant women as sexually promiscuous stems from hypersexualized and erotically charged colonial representations of them (). Microaggressions in this sub-theme were often characterized by the stereotypical assumptions that they immigrated to Portugal to be sex workers or to steal Portuguese women's husbands, and that they seek relationships with Portuguese men for economic interest or to obtain visa/citizenship:

I was in class, during the break, and a girl came to talk to me, she was Portuguese, and she asked: “How is it to be Brazilian here [in Portugal]?”, and I was like, “It's okay” […] Then she turned around and without giving any context, she just said “My father ran away with a Brazilian woman”. And what should I do about that? I am not going to run away with your father. I swear, I did not have any reaction. (P18—Brazil, White, 6 years in Portugal)

In Portugal, immigrant women are often associated with the sex market, accused to be “family wreckers” and “husband thieves,” and even blamed for the increase in divorce rates and diversification of family models in Portugal (; ). The origin of these representations has been traced back to the first eroticized descriptions of indigenous women, often depicted and objectified as the natural bounty of the colonized land and further reinforced by the arrival of Black slaves in Brazil, which increased the idea of a “sex paradise,” while opposing the representations of the sexual purity linked to European women (; ; ). It is also interesting to note that microaggressions related to this theme were often perpetuated precisely by Portuguese women, further revealing the intricate complexity of participants’ intersectional experiences.

Sexual Microassaults. A specific sub-theme was created for sexual microassaults (), which represented the largest portion of microaggressions in this theme. We categorized as sexual microassaults those incidents of sexual harassment which were too explicit to be considered sexual objectification microaggressions, but which, at the same time, were too covert and/or socially normalized to be considered macro-aggressions (). These microassaults included, for example, catcalling and ambiguous sexual advances:

I went to the minimarket next to my house, I had never been there before, and there was this man, the attendant […] he looked at me and said, “Are you Brazilian?”, and I said, “Yes, I am Brazilian”. And he did something like this with his hands [makes a gesture with the hands], like delineating the shape of a [curvy] body, and said “I love Brazilians”, […], as if being Brazilian was that. And then he started to act in a very wrong way with me, and I said, “Look, what you are doing here is not cool. I did not come here to flirt with you or hear your comments. I came to buy my groceries.” (P51—Brazil, Black, 6 months in Portugal)

Once again, the intersection of gender and immigrant status giving rise to colonial representations of immigrant women as colonizable bodies serves to understand the ambiguity of these subtle forms of sexual harassment, which may be considered unacceptable if directed at Portuguese women but remain unsanctioned when targeting immigrant women.

Assumptions of Beauty and Exotization

This theme is also specifically related to the intersection of gender and immigrant status or ethnicity and contained microaggressions related to the judgments and pressures of immigrant women's physical appearance (; ; ). For example, participants reported experiences related to colorism, assumptions of attractiveness, and ascription of beauty standards (; ; ). Whereas the above-described theme Erotization and Hyper-Sexualization refers to beliefs about the sexuality of immigrant women, microaggressions in this theme occurred when immigrant women were deemed attractive or unattractive (and consequently objectified) based on certain appearance standards with reference to a specific ethnic phenotype:

Once, I was in a party and a Portuguese guy approached me, I said I did not want to do anything with him, that I was not interested […]. Then he said, “are you Brazilian?”, and I said “Yes, I am”. Then he looked me up and down, and I thought that was wonderful because then he managed to be offensive with everyone, he said, “this is what I like about Brazilian women, this miscegenation, because Brazilian women are White women with Black women's bodies”. Of all the things I ever heard, I thought that that was the most absurd. (P14—Brazilian, White, 5 years in Portugal)

Whereas Brazilian women were often targeted by apparently complimentary comments referring to the “Brazilian phenotype” as the perfect product of miscegenation (i.e., mixing the perceived beauty of Whiteness with the hypersexualized representation of Indigenous and Black bodies), participants from the Portuguese speaking African countries were targeted by the belief that darker skin color, as well as Black phenotypical traits, were unattractive or undesirable (): “I have seen another Black girl, but she was not as pretty as you are, her nose was more like this or that” [P21—Guinea Bissau, Black, 20 years in Portugal]. Finally, some participants reported being treated as or being called “exotic” because of stereotypes related to women from their country of origin (; ):

Once I met a guy who would call me “my Amazonian Indian [i.e., indigenous]”. People, I am from São Paulo, I have never even been close to the Amazons, and I do not have the face of an Indian [i.e., indigenous]! My family, I have a grandmother who is German, my sister is blond, it has nothing to do… It is not possible. (P26—Brazil, Mixed origin, 4 years in Portugal)

Within the context of post-colonial gendered relations, the term “exotic” recalls the connotations of a “stimulating or exciting difference, something with which the domestic could be (safely) spiced” (, p. 87), mixed with the eroticized and primitivistic representations of Indigenous women's objectified bodies.

Representations of the Portuguese Colonizers

Benevolent, Just, and Unprejudiced: How the Colonizers See Themselves Through the Lenses of Luso-Tropicalism

Some of participants’ accounts of microaggressions also offered insights on the culturally shared representations held by Portuguese people regarding themselves and their historical role as colonizers. These representations were deeply ingrained in the luso-tropical belief of an innate openness to cultural diversity, which allows them to deny racism and discrimination and to reframe the Portuguese colonial project as a friendly interracial/intercultural relation that brought direct benefits for the colonized (; ).

Denial of Individual and Systemic Bias

This theme was related to statements in which Portuguese people denied the existence of their personal biases, as well as the existence of systemic and institutional discrimination, and failed to acknowledge that ethnicity, gender, or immigrant status play a role in shaping participants’ experiences in Portugal ():

Last year we organized an anti-racism education session. It was a quite impactful initiative; and a significant number of Portuguese participants ended up saying that there is no racism, no discrimination, that we are all equal, and they didn’t see color. I think this really reflects how people perceive us, immigrants […] When they claim there is no racism and discrimination, it's a lie; […] They will always deny it, saying they have a Black friend, but unfortunately, that's not true. (P20—Cape Verde, Black, 30 years in Portugal)

Color-evasiveness (; ; ; ) and the myth of meritocracy (; ; ) are other examples of microaggressions included in this theme. These beliefs about the unprejudiced nature of the Portuguese are one of the key components of luso-tropical representation identified in previous studies (), and appear particularly problematic as they deny the existence of individual prejudice and structural inequality, ultimately invalidating immigrant women's experiences of discrimination and creating spirals of silence that fail to address the issue ().

The “Good Colonizer” Myth

This theme was inductively derived from microaggressions referring to the luso-tropical myth of the Portuguese being “good colonizers”; that is, substantially benevolent, especially in comparison to other European colonizers such as Spain, France or Belgium (; ). This theme was also related to the idea that colonization brought social and economic development to otherwise backward countries:

[Some international students] did a work group about the Portuguese maritime expansion […] They started speaking and the professor interrupted them and said that their work was awful, that it was not enough for the Portuguese academic level […] Then she turned to me […] and she said “Everyone knows that Brazil did not have any culture. It is absurd that you are saying that those places already had a culture, because who brought culture to Brazil were the Portuguese. If we had never colonized them, what would be of Brazil? There would not be anything there”. And she looked at me and said, “Isn’t it true?”. (P14—Brazil, White, 4 years in Portugal)

These luso-tropical representations obscure the violent, exploitative nature of colonization to depict it as an act of worth of merit and honor, which is a source of pride and a central component of the Portuguese national identity, acting as a catalyst to positive national identification and collective self-esteem. These sets of beliefs have been found to persist among young people in Portugal (; ) and to be related to restrictive dimensions of identity, such as nationalism and bias against immigrants (; ).

Discussion

Although the microaggressions framework has provided a robust foundation for the study of subtle discrimination since its introduction (), the experiences of foreign-born immigrant women, especially in non-U.S. contexts, have been overlooked. Additionally, little research has been conducted to examine the sociocultural factors shaping microaggressions, particularly in post-colonial societies. Therefore, the contribution of the present study to the current state-of-the-art is twofold. First, this work extends the application of the microaggressions research framework by proposing a taxonomy for Gendered Colonialist Microaggressions directed at foreign-born immigrant women. Throughout a total of ten focus groups, participants reported more than 300 microaggressive incidents that were categorized into nine themes. Seven of these themes aligned with U.S.-developed taxonomies, indicating cross-cultural similarities, while two new themes emerged, potentially specific to post-colonial contexts. This suggests that although some experiences of immigrant women are similar to those of other populations, certain aspects remain unique to our study group. For instance, while microaggressions related to assumptions of beauty and exotization have been documented in previous studies on Black women (), our findings reflect colonialist beliefs specific to the Portuguese context, particularly regarding miscegenation and the experiences of Brazilian women (). Additionally, we identified two new themes—Language and communication stereotypes, and pathologizing and The “good colonizer” myth—likely specific to Portuguese cultural and colonial history and possibly applicable to other European contexts with similar sociohistorical patterns (e.g., France, Spain, the UK).

Second, by drawing on the literature contextualizing microaggressions as an individual experience of discrimination (e.g., ) embedded in larger social structures of privilege and oppression (e.g., ), the present study offers a framework (Figure 1) to understand the implications of these subtle forms of discrimination at both the psychological and sociocultural levels. At the psychological level, recipients of microaggressions individually engage in an energy-depleting process to identify and interpret the subtle messages conveyed (top of the pyramid in Figure 2; ): “you do not belong here” (i.e., Second-Class Citizenship, Rejection, and Invisibility), “the language you speak is inherently wrong” (i.e., Language and Communication Stereotypes and Pathologizing), “you are sexually promiscuous” (i.e., Assumptions of Promiscuity). Due to their ambiguous, chronic, and cumulative nature, microaggressions have been found to predict negative psychological outcomes (e.g., psychological distress, depression, anxiety) among different underprivileged groups (). For first-generation immigrant women, microaggressions may also play a broader role in the process of psychological acculturation (). This might be especially relevant as our findings indicated that the longer participants lived in Portugal, the more microaggressions they reported. Over time, microaggressions may lead to reduced intergroup contact with members of the receiving society, impairing sociocultural adjustment and affecting social identity outcomes (). In Portugal and other historically colonizing nations, gendered colonialist microaggressions have the potential to affect the lives of thousands of immigrant women as well as their relations with members of the receiving societies. Yet, to the best of our knowledge, no studies have examined microaggressions in the context of this population's psychological acculturation ().

At the sociocultural level, our findings highlight how microaggressions are rooted in structures of privilege and oppression and shaped by historical representations of colonialism. Using post-colonial feminist discourse theory (; ; ), we generated four macro-themes (bottom of the pyramid in Figure 2) illustrating the societal discourses underlying microaggressions. Previous research has shown that Portuguese colonial ideologies promoted a representation of colonization as essentially non-racist, emphasizing its civilizing mission () and the positive effects of Portuguese miscegenation in the tropics (). However, discourses related to the good colonizer myth do not actually reflect benevolent colonial practices (there is no such thing as benevolent colonialism), but instead serve to justify a hierarchy within Portuguese colonial society (). Indeed, these beliefs were (and still are) dependent on the perception of colonized groups as intrinsically inferior. For example, despite having obtained its independence in 1822, Brazil is still seen as a Portuguese creation, therefore perpetually cast in a subordinate role to Portugal (). In line with this literature, our findings illustrate how microaggressions perpetuate colonial ideologies about the superior and civilized nature of the Portuguese colonizers, together with culturally shared representations of immigrant women as “subaltern others” ()—inherently inferior, primitive, colonizable bodies. These narratives—deeply ingrained in society—are identifiable not only in individual experiences, but at the broader sociocultural level, being perpetuated through, for example, institutions (), schools (), the media (; ), and literature ().

Limitations

This study advances the understanding of microaggressions in the context of post-colonial relations; however, it also has some limitations. First, the focus groups were conducted online via Zoom. While this format effectively reduced geographical barriers and enabled the participation of immigrant women living across the Portuguese territory, it may have inadvertently excluded individuals with limited digital proficiency or those lacking access to the Internet or a device with a functioning camera and microphone. Second, our choice of providing participants with a description and examples of microaggressions was intended to facilitate their remembrance of microaggressive incidents while also confirming the applicability of previous research findings to a different context; yet, it might have limited participants’ responses to the range of themes that were initially presented to them. Third, the deductive approach adopted to understand to what extent pre-existing microaggressions taxonomies would be applicable to the experiences of immigrant women in Portugal may have bound our analysis to previous interpretations generated in other cultural contexts and with other populations. Additionally, advised that, although codebook TA is a useful tool for a more structured approach to the data, it can also produce themes that map closely to the interview questions, resulting in a less organic and open interpretation of the data compared to reflexive TA.

Directions for Future Research

The findings and limitations of this study offer insights for future research. First, racialized immigrant women may encounter more microaggressions as well as qualitatively different ones (e.g., due to colorism), and thus deserve separate attention. Second, given the important cultural differences across the CPLP countries, and that the existing literature mostly focuses on Brazilian women, future studies may consider restricting their focus on single Portuguese speaking African countries and/or include additional (or alternative) intersectional categories (e.g., sexual orientation, age, socio-economic status) to achieve a deeper understanding of the complexity underlying immigrant women's experiences of microaggressions. Third, additional research is warranted to examine the recurrence of microaggressions related to the good colonizer myth (and more generally to luso-tropical beliefs). Fourth, the themes presented in this study may be useful to examine the experiences of immigrants in other European countries with similar colonial legacies and linguistic ties (e.g., Ecuadorian and Colombian immigrants to Spain, Senegalese to France, Indians in the UK). More research is needed in post-colonial settings, as well as in non-W.E.I.R.D. cultural contexts. Large-scale, international, and cross-cultural studies are fundamental to understand the incidence of microaggressions for migrant populations across different countries. Finally, the present study raises several questions about the perception of microaggressions within the process of psychological acculturation () that have yet to be answered: what is the role of language proficiency in the perception of microaggressions? What underlying psychological processes are at play in the interpretation of subtle discriminatory cues for individuals born in a cultural context different to the receiving society? How do individual differences play a role in making attributions to prejudice? How do immigrants cope with discrimination when it is socially normalized? And finally, what are the psychological correlates of perceiving microaggressions for immigrant groups with multiply marginalized identities?

Practice Implications

The present study has important implications for professionals working with migrant communities, including practitioners, advocates, policymakers, and stakeholders. While microaggressions are often downplayed as minor or insignificant, our findings highlight how they carry harmful messages that can potentially affect immigrant women's well-being and integration into the Portuguese society. Hence, we urgently call for interventions to raise awareness about microaggressions and post-colonial representations in the Portuguese context. Our findings can inform educational initiatives aimed at challenging colonial discourses within the Portuguese society by promoting empathy and cultural sensitivity. For instance, diversity education programs could employ vignettes and case studies informed by the incidents reported in this study to exemplify different themes and types of microaggressions. Previous studies examining microaggressions via the Critical Incident Technique () have proposed vignettes to be implemented in training programs for healthcare providers (). These vignettes may not only facilitate the identification of microaggressions (top of the pyramid in Figure 1) and their psychological implications, but also promote an in-depth understanding of the societal beliefs and representation in which they are rooted (bottom of the pyramid). In this context, educational programs could also consider employing different terms than “microaggressions,” since it has been suggested that the prefix “micro” can be misinterpreted and minimize the harm and severity of this form of discrimination ().

Furthermore, our results can support the development of resources and services tailored to the needs of immigrant women. Mental health and psychosocial support programs might benefit from acknowledging microaggressions, their societal roots and harmful consequences. Counselors and therapists should recognize microaggressions as a potential chronic stressor, which can lead to negative emotional, cognitive, and behavioral consequences (). Accessible resources and support networks could also be established to empower immigrant women, equipping them to cope with and respond to microaggressions, and creating safe spaces for discussion and promotion of individual and collective action.

In conclusion, the present study illustrates how microaggressions, although often seemingly innocuous, are powerful social instruments that maintain and reinforce social inequalities. Our findings can support researchers, activists, and policymakers in challenging the socially normalized nature of microaggressions, “making the invisible visible” (, p. 106), and ultimately promoting inclusivity and quality at different societal levels.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of students from the course of Advanced Research Methods in Psychology at Iscte-IUL, who contributed to the data collection.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The present study has been funded by a merit-based scholarship to students of the third cycle of the School of Human and Social Sciences at Iscte-IUL to Elena Piccinelli and a research grant from the FCT (2022.05941.PTDC) to Filipa Madeira.

ORCID iDs Elena Piccinelli https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4441-2125

ORCID iDs Christin-Melanie Vauclair https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4940-1185

References

- Ashcroft B., Griffiths G., Tiffin H. (2007). Post-colonial studies: The key concepts (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Bagno M. (2007). Preconceito linguístico: o que é, como se faz (49th ed.). Edições Loyola.

- Bettache K. (2022). The W.E.I.R.D. microcosm of microaggression research: Toward a cultural psychological approach. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(4), 743–748. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221133826

- Bhabha H. K. (1983). The other question. Screen, 24(6), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/24.6.18

- Birmingham D. (2003). A concise history of Portugal (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107280212

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2021). Can I use TA? Should I use TA? Should I not use TA? Comparing reflexive thematic analysis and other pattern-based qualitative analytic approaches. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 21(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12360

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2022). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

- Buettner E. (2021). Europe and its entangled colonial pasts. In Timm Knudsen B., Oldfield J., Buettner E., Zabunyan E. (Eds.), Decolonizing colonial heritage: New agendas, actors and practices in and beyond Europe. (critical heritages of Europe) (pp. 25–43). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003100102-3

- Butler A., Abawi Z. (2021). Deconstructing citizenship and belonging: Refugee student integration and microaggressions in Ontario schools. In Corkett J. K., Cho C. L., Steele A. (Eds.), Global perspectives on microaggressions in schools: Understanding and combating covert violence (pp. 78–92). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003089681-8

- Cabecinhas R., Feijó J. (2010). Collective memories of Portuguese colonial action in Africa: Representations of the colonial past among Mozambicans and Portuguese youths. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 4(1), 28–44. https://doi.org/10.4119/ijcv-2813

- Capodilupo C. M., Nadal K. L., Corman L., Hamit S., Lyons O. B., Weinberg A. (2010). The manifestation of gender microaggression. In Sue D. W. (Ed.), Microaggressions and marginality: Manifestation, dynamics, and impact (pp. 193–216). John Wiley & Sons.

- Cohen C. E., Strand P. J. (2022). Microaggressions and macro-injustices: How everyday interactions reinforce and perpetuate social systems of dominance and oppression. Understanding and Dismantling Privilege, XII(2), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3937349

- Correia C., Neves S. (2010). Ser Brasileira em Portugal – Uma abordagem às representações, preconceitos e estereótipos sociais. In Actas Do VII Simpósio Nacional de Investigação Em Psicologia (pp. 378–392). Universidade Do Minho.

- Crenshaw K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics. Living With Contradictions: Controversies in Feminist Social Ethics, 1989(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429499142-5

- de Matos P. F. (2019). Racial and social prejudice in the colonial empire: Issues raised by miscegenation in Portugal (late nineteenth to mid-twentieth centuries). Anthropological Journal of European Cultures, 28(2), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.3167/ajec.2019.280203

- De Oliveira Braga Lopez R. (2011). Racial microaggressions and the Black immigrants living in Portugal [Doctoral Dissertation]. John F. Kennedy University.

- Flanagan J. C. (1954). The critical incident technique. Psychological Bulletin, 51(4), 327–358. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061470

- França T., de Oliveira S. P. (2021). Brazilian migrant women as killjoys: Disclosing racism in “friendly” Portugal. Cadernos Pagu, 2021(63), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449202100630001

- Furukawa R., Driessnack M., Colclough Y. (2014). A committee approach maintaining cultural originality in translation. Applied Nursing Research, 27(2), 144–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2013.11.011

- Gadson C. A., Lewis J. A. (2022). Devalued, overdisciplined, and stereotyped: An exploration of gendered racial microaggressions among Black adolescent girls. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 69(1), 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000571

- Gartner R. E. (2021). A new gender microaggressions taxonomy for undergraduate women on college campuses: A qualitative examination. Violence Against Women, 27(14), 2768–2790. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801220978804

- Gartner R. E., Sterzing P. R. (2016). Gender microaggressions as a gateway to sexual harassment and sexual assault: Expanding the conceptualization of youth sexual violence. Affilia - Journal of Women and Social Work, 31(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109916654732

- Gomes M. S. (2013). O imaginário social<Mulher Brasileira>em Portugal: Uma análise da construção de saberes, das Relações de Poder e dos Modos de Subjetivação. DADOS – Revista de Ciências Sociais, 54(6), 867–900. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0011-52582013000400005

- Hall J. C., Crutchfield J. (2018). Black women’s experience of colorist microaggressions. Social Work in Mental Health, 16(4), 491–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2018.1430092

- Holtgraves T. (2022). Microaggressions in context: Linguistic and pragmatic perspectives. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(4), 733–737. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221133824

- Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE). (2023). População. https://www.ine.pt/xportal/xmain?xpgid=ine_tema&xpid=INE&tema_cod=1115

- Jurado D., Alarcón R. D., Martínez-Ortega J. M., Mendieta-Marichal Y., Gutiérrez-Rojas L., Gurpegui M. (2017). Factors associated with psychological distress or common mental disorders in migrant populations across the world. Revista de Psiquiatría y Salud Mental (English Edition), 10(1), 45–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rpsm.2016.04.004

- Kashima E., Safdar S. (2020). Intercultural relationships, migrant women, and intersection of identities. In Cheung F. M., Halpern D. F. (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of the international psychology of women (pp. 434–448). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108561716.036

- Lewis J. A., Mendenhall R., Harwood S. A., Browne Huntt M. (2016). “Ain’t I a Woman?”: Perceived gendered racial microaggressions experienced by Black women. Counseling Psychologist, 44(5), 758–780. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000016641193

- Lewis J. A., Neville H. A. (2015). Construction and initial validation of the gendered racial microaggressions scale for Black women. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 62(2), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000062

- Lugones M. (2008). The coloniality of gender. Worlds and Knowledges Otherwise, 2, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783839461020-002

- Lui P. P., Quezada L. (2019). Associations between microaggression and adjustment outcomes: A meta-analytic and narrative review. Psychological Bulletin, 145(1), 45–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000172

- Malheiros J. (2007). Imigração brasileira em Portugal. Alto Comissariado para a Imigração e Diálogo Intercultural (ACIDI).

- McAuliffe M., Triandafyllidou A. (2021). World Migration Report 2022. International Organization for Migration (IOM).

- McCall L. (2005). The complexity of intersectionality. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 30(3), 1771–1800. https://doi.org/10.1086/426800

- McClintock A. (1995). Imperial leather: Race, gender, and sexuality in the colonial contest. Routledge.

- McClure E., Rini R. (2020). Microaggression: Conceptual and scientific issues. Philosophy Compass, 15(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/phc3.12659

- Mekawi Y., Todd N. R. (2021). Focusing the lens to see more clearly: Overcoming definitional challenges and identifying new directions in racial microaggressions research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 16(5), 972–990. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691621995181

- Morgan D. L. (1997). Focus groups as qualitative research. Sage Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412984287

- Nadal K. L. (2011). The racial and ethnic microaggressions scale (REMS): Construction, reliability, and validity. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 58(4), 470–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025193

- Nadal K. L., Mazzula S. L., Rivera D. P., Fujii-Doe W. (2014). Microaggressions and Latina/o Americans: An analysis of nativity, gender, and ethnicity. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 2(2), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/lat0000013

- Ng S. H. (2007). Language-based discrimination. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 26(2), 106–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X07300074

- Nosek B. A., Alter G., Banks G. C., Borsboom D., Bowman S. D., Breckler S. J., Buck S., Chambers C. D., Chin G., Christensen G., Yarkoni T. (2015). Promoting an open research culture. Science, 348(6242), 1422–1425. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aab2374

- O’Connor C., Joffe H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406919899220

- Oliveira C. R. d. (2023). Indicadores de integração de imigrantes: relatório estatístico anual 2023 (Imigração em Números – Relatórios Anuais 8) (1st ed.). Observatório das Migrações. https://www.om.acm.gov.pt

- Osanloo A. F., Boske C., Newcomb W. S. (2016). Deconstructing macroaggressions, microaggressions, and structural racism in education: Developing a conceptual model for the intersection of social justice practice and intercultural education. International Journal of Organizational Theory and Development, 4(1), 1–18. https://www.nationalforum.com/Electronic%20Journal%20Volumes/Osanloo,%20Azadeh%20Deconstructin%20Racism%20in%20Education%20IJOTD%20V4%20N1%202016.pdf

- Piccinelli E., Martinho S., Vauclair C.-M. (2021). Expressions of microaggressions against women in the healthcare context: a critical incident approach. Psique, XVI(1), 44–64. https://doi.org/10.26619/2183-4806.XVI.1.3

- Piccinelli E., Vauclair C.-M., Dollner Moreira C. (2024). The role of perceived forms of discrimination within the psychological acculturation process of first-generation immigrants: A scoping review. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/00220221241255615

- Pierce C. (1970). Offensive mechanisms. In Barbour F. B. (Ed.), The Black seventies (pp. 265–282). Porter Sargent.

- Ryan K. E., Gandha T., Culbertson M. J., Carlson C. (2014). Focus group evidence: Implications for design and analysis. American Journal of Evaluation, 35(3), 328–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214013508300