The conviction that values are central to a scientific psychology has had many distinguished adherents (e.g., ; ; ; ; ). James characterized his life’s work in terms of values: “I have been moving toward a psychology of values instead of a psychology of stimulus” (; cited in , p. 296). Solomon , pp. 350–363) claimed that values are crucial to psychology and argued that they should not be confused with desires, needs, habits, preferences, goals, rules, or emotional reactions. Rather, values are the standards by which all of these are judged. Despite these claims, theoretical work on values has rarely played a central role in the discipline (). Nevertheless, a variety of more recent voices have tried to call attention to the need to address values more forthrightly (e.g., ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ; ).

We believe that one of the key reasons that values have not played a more visible or vital role in orienting research within psychology is that they have often been conceptualized in exactly the ways that counseled against. Values have been portrayed as beliefs about “desirable, trans-situational goals” that are “in the eye of the beholder, not in the object of perception” (, p. 63), as pleasurable experiences (), and as expected utility (). Despite their differences, all of these approaches to values locate them at the level of individuals and what they find desirable, pleasurable, or useful. Others have framed values more broadly in terms of social norms (e.g., ) or inclusive fitness (e.g., ), highlighting that values cannot exist independently of their relation to social, biological, and historical-cultural environments; nevertheless, it is dubious that values can be limited to single mechanisms or particular times and places. A few have tried to locate values in the environment, as properties of objects or events that are objective resources for people’s actions (e.g., ; ). Finally, some have claimed that values are irrelevant, or even a hindrance, to proper psychological accounts (e.g., ; ).

In this article, we explore an alternative approach, which we will refer to as ecological values theory, which treats values as ecosystem constraints on fields of action within that system. From this perspective, values are neither subjective nor objective; rather, they are about relationships and the demands that the ecosystem places on those relationships (; ). Thus, they cannot be seen as belonging to individuals, societies, or environmental objects. Values play a crucial role in defining and evaluating skilled actions and practices (e.g., driving; conversing); thus, taking them into account is an important dimension of the research task (e.g., ; ; ). Often researchers fail to address values carefully, not because of some metatheoretical commitment, but simply because they assume that they already know what is good and what is important with respect to the psychological skills or practices they are investigating. However, situations and actions are often more complex than imagined ().

We begin by providing an overview of ecological values theory, arguing for the constitutive role that values play in psychological acts. Second, we explore how this approach has been developed and applied in two domains, social interaction tasks and perception-action skills. Some of the cases we consider are ones that have previously been explored in terms of an ecological account; others are novel. In both kinds of cases, we try to extend and enrich previous claims with the intention of testing the integrity and usefulness of the theory. Along the way, we note some methodological strategies that may prove useful in revealing values-realizing dimensions of psychological activities. Finally, we consider briefly some prospects for ecological values theory, as well as some of the challenges that face such accounts.

The Problem of Action and the Necessity of Values

Wolfgang , p. 38–39) argued that psychology as a science would “destroy” itself if it did not take values seriously. He proposed that in perceiving and acting, one is confronted with a sense that something ought to be done within the situation; this sense of requiredness motivated and guided one’s activity. What was being sensed were values, which were demands that called for action but were not dependent on the self (). , p. 127) elaborated this sense of requiredness into his widely cited account of affordances, which are meaningful action opportunities provided by the environment “for good or for ill.” Vision, he claimed, hunted for increasing comprehensiveness, clarity, and other values (, p. 219, 255). However, most researchers do not see values as what organizes and directs action; instead, they are likely to appeal to goals, rules, and/or natural laws. Are these sufficient? If not, what are values and how do they relate to laws, rules, and goals?

The account of values to be explored in this article is one that was first sketched in and applied to developmental and social psychological research (e.g., ; ; ), as well as critical issues in perception and action (e.g., ; ). Three roots of the theory were explored: Gibson’s ecological psychology (e.g., ; , , ; ; ; ), Gestalt psychology (e.g., ), and the work of Martin and his colleagues on the character of values in thinking and reasoning (, ; ). Finally, various concerns raised in philosophy of science relative to values were included (e.g., ; ; ; ; ). Thus, ecological values theory is situated in a rich background of previous work, which has highlighted the centrality of values to scientific accounts of psychological acts. , , , , and , provide further background on the ecological concern for values, including the social and moral dimensions of action and perception.

Ecological values theory (e.g., , ; ) claims that psychological accounts framed only in terms of laws, rules, and goals are not sufficient to explain acting and perceiving. Rather, values are essential to defining and evaluating actions; they provide the larger context in which laws, rules, and goals function. Consider a simple example: A person wants to drive from their house to their grandmother’s home. To achieve this goal, they will need to act so as to take advantage of many natural laws (e.g., gravity, friction, and optics), directing the movements of the vehicle in the right direction to reach their goal. Along the way, movements will be constrained by many rules, as well (e.g., roadways, lanes, and signals). Driving is constrained by goals, natural laws, and rules; however, by themselves, they are not enough.

For driving to exist and to function effectively, laws, rules, and goals must come together in the right way. Driving is an enormously complex ecosystem of people, activities, and artifacts that are interdependent. What are the common goods that define the driving ecosystem and its many constituent components (e.g., car designers, road maintenance crews, fuel distributors, repair facilities, traffic engineers, pedestrians, and drivers), so that driving can be sustained for many drivers, not just one? Answering questions about rightness and common goods requires an appeal to values. For driving to function properly, both at the individual and systemic levels, it must be jointly constrained by many values, among them, accuracy, tolerance, speed, safety, freedom, trust, comfort, equality, justice, stability, and flexibility. To elaborate very briefly on these values, drivers must come close to many other cars and obstacles (accuracy) and yet not too close (tolerance), while moving quickly and freely among others who are doing the same. Generally speaking, they all have equal rights to the road and must trust that others, as well as themselves, are concerned for the safety and justice of the ecosystem as a whole and all users of the road (comprehensiveness) who participate in it. For speed, safety, freedom, justice, and other values to be realized, drivers will find themselves constrained to be remarkably stable in some ways and constantly flexible at the same time. All of these constraints together guide and direct the actions that constitute driving, making it possible for drivers to set out on a journey with confidence.

Our brief look at the driving ecosystem only begins to scratch the surface of the complexities that face action in this domain. A host of other issues tied to values need to be addressed (e.g., issues of economy, beauty, health, accessibility, and environmental degradation); however, even our cursory consideration has shown that driving does not emerge and sustain itself without attention to values, not just goals, laws, and rules. The hypothesis we want to explore is that this is true of all action and interaction, which means that researchers will need to address values carefully if they are to do justice to the actions they study.

Values as Ecosystem Constraints on Fields of Action

Having laid out a larger frame of reference for values, we turn now to more specific claims about fields of action within ecosystems, and how values enable and guide actions. First, we provide an overview of the theory, laying out some basic claims, sometimes using driving examples to illustrate. However, far more extensive examples from research in social interaction and perception-action studies are then offered to provide specificity and substance to the theoretical abstractions. The hope is that the theory helps to see the examples in a different light, while the research helps to clarify the theoretical claims, and show their range of application.

Values are Multiple, Heterarchical, and Frustrated

Psychological acts of any complexity are jointly constrained and legitimated by many values rather than by a single value or a fixed hierarchy of values. Any given value cannot be realized in isolation, but only jointly as other values are also realized (). Driving demands accuracy (e.g., direction) and speed (e.g., efficiency), but without attention to safety, justice, tolerance, and many other values, accuracy and speed would quickly be undermined. The working hypothesis of ecological values theory is that values function as a community of criteria, mutually constraining each other so that each of them is realizable in the long run only if the other values are also honored.

Values function this way because they are heterarchically organized. Each value is constrained by all the other values, without control being vested in any one of them (; ). , p. 3), the first to use the term, claimed that “for values there can be no common scale.” If this is so, then values are not scaled in linear hierarchies or fixed, polar oppositions, as is often claimed (e.g., ; ); rather, they are interdependent and mutually constraining, supporting each other in a dynamic tension. Each value leads and follows other values at various times during a task, as well as across tasks; hierarchical relations are temporary and reversible. In driving, for example, speed and accuracy may take priority over safety at one place or time, but then reverse at another. These are not simple tradeoffs; sometimes, safety might require increased speed and tighter tolerances, thus requiring greater accuracy ().

The heterarchical relation of values leads to skilled activities that can be seen as frustrated (). The term was first used in physics (e.g., ) to describe systems that are “subject simultaneously to very many different physical requirements that they cannot possibly satisfy fully” (, p. 91). Given that values are in tension and yet function cooperatively, the result is that no one value can be fully realized, in the way that a goal might be achieved (, p. 41). Control of action is distributed, a balanced tension between order and disorder. As one becomes more skilled (e.g., juggling; ), one comes closer to the edge of what is possible rather than settling into some sort of “comfort zone.” Skilled action of any complexity works to realize a juggled balance of values that is continuously creative rather than being some sort of rule-following procedure that follows the same trajectory every time (i.e., repetitive).

Values are Obligatory and Enabling

Values are ecological; they are the “global constraints on an ecosystem,” or the “boundary conditions that provide for the dynamics of the system and the directedness of animate activity within it” (, p. 590). They are not natural laws, rules, or goals, although they are related to each of these. Values are obligatory. Drivers, for example, are obligated to look where they are going. The obligation is not a social convention, or a natural law (i.e., one is not caused to look where one ought to be looking). Looking is not the goal of driving either; rather, it is a responsibility. It is required because the values of driving (e.g., accuracy; tolerance; safety) cannot be realized otherwise; it is a necessary constraint that makes the freedom of driving possible. Values work together in concert as a set of boundary conditions that create a task-space, or a field of action, that is open to creative activity within those constraints.

In one sense, values restrain, but in another sense, they are enabling. Driving in a way that is both accurate and flexible is demanding, but these demands enable driving to be both fast and safe. Paradoxically, freedom of action emerges from constraints, promoting creativity and robust functionality (e.g., see ; for examples of enabling constraints enhancing visual systems and social organizations).

Although values obligate responsible action, the tolerances for failing to realize values are often more relaxed than those for ignoring lawful relations. Drivers can sometimes be inaccurate, unfair, or unsafe in their actions, without immediate negative consequences; nevertheless, such actions always threaten to collapse the field of action (e.g., collision; gridlock). The greater elasticity of values relative to laws has tempted some to think that values are really nothing but rules, that is, arbitrary guidelines that are socially constructed and enforced. However, safety, freedom, and truth, for example, do not exist only on someone’s say-so. This does not mean that humans cannot argue about how safety, freedom, and other values are best realized in specific circumstances, but values are real goods that are necessary criteria for evaluating activities. If this were not the case, then productive arguments themselves would not be possible, whether about values or anything else.

Goals are specifiable end states that can be achieved through action, and rules provide specified procedures for reaching those goals. However, goals and rules are too definite and too restricted to legitimate action (; ) without becoming subject to an infinite regress of “rules on rules” or a series of meta-goals (). Rules always depend on a larger “good faith” context , pp. 259–260) that depends on values (). Goals and rules are personal and social constructions, and must be chosen, organized, and justified. This becomes particularly clear when goals or rules need to be revised. Revisions are rarely arbitrary; rather, the changes are justified by appeals to justice, freedom, safety, economy, accuracy, or other values (e.g., ).

To highlight the necessity of values is not, however, to shortchange the importance of laws, rules, and goals. Laws function as widely distributed (e.g., universal) space-time stabilities, while rules function as more localized or time-limited stabilities. Both are nested within values-realizing dynamics. Goals can be a means to realizing values, and rules can be a means of realizing goals, all within the possibilities provided by natural laws. It is values—a driving ecosystem that makes speed, safety, accuracy, comfort, efficiency, and other values possible and probable—that provide the criteria for generating rules and conventions, and that hold participants responsible for taking lawful constraints, such as varying road conditions, into account.

Values are Emergent, Self-Critical, and Dialogical

Values have an intrinsic developmental dynamic. The heterarchical tensions among values work together cooperatively to motivate continued perceptual learning and skill development. Values are real but they are not objects waiting to be picked up by eye or hand, but relationships that emerge through engagement over time. There is always more to learn; for example, as one learns to drive, the precision and accuracy of actions increases; later, as one ages, there may be decreases in accuracy and comprehensiveness (e.g., leaving greater gaps between vehicles and driving only during daylight; ). In another sense, values themselves are increasingly revealed (i.e., realized) as development and history unfold ().

This cooperative, developing dynamic is what allows values to be self-critical and therefore legitimating. Any goal one chooses to pursue cannot be criticized from the point of view of the goal itself (). On the other hand, “every attempt to explicate a value is subject to criticism from the point of view of the value itself” (, p. 68). Thus, someone may come to a truer appreciation of truth, or come to realize that their safety practices are unsafe in some ways not noticed previously. Furthermore, each value is judged by all the values (). Values work because any one value does not function as an isolated criterion, but only in the context of mutually interdependent values (, p. 332). Therefore, in an important sense, values are continually revising activities in self-organizing fashion as those activities unfold.

Participants contribute to the ecosystem and its development, as well as being constituted, guided, and judged (i.e., evaluated) by it. Values define fields of action within ecosystems. Such fields may be viewed as dialogical (or social): Fields of action require ongoing coordination and cooperation, since the fields are jointly instantiated and defined. For example, one person’s ability to converse depends upon what another’s utterances offer as possibilities, and vice versa (e.g., ); similarly, one driver’s field of action co-varies with other drivers’ fields. All agents are required to commit themselves to realizing values in the system (e.g., driving; conversing) and to trusting that other relevant agents will be (or have been) careful to realize values as well ().

What Values Afford: Locating, Learning, and Legitimating

Values are not located in any isolated aspect of an ecosystem but are relationships that allow the ecosystem to function, develop, and flourish. To return to the driving example, safety, accuracy, justice, and the other values of driving are relational; they do not exist as a property of drivers, or their vehicles, or the roads they drive on. They are not beliefs; they are actual and potential relations in the world. Realizing values such as safety and accuracy depends on how drivers, vehicles, traffic systems, weather, and many other sets of variables interact. Values do not exist within components of the driving ecosystem, but across relationships within a properly functioning ecosystem as a whole.

The various values that define driving (e.g., speed, accuracy, and safety) are the relationships that make it a skill and thus, allow it to be evaluated and improved. Values are the large-scale requirements (boundary conditions) that indicate when some activity (e.g., driving; reasoning; listening) is, or is not, going right (i.e., contributing to the well-being of the ecosystem as a whole). Without a larger ecology of values, individuals and societies would not be able to critique themselves, including their goals, rules, and uses of laws. Nor would they have any basis for creative attempts at improving their way of life (e.g., ). argued that beliefs, goals, and desires depend on values, not the reverse; and , p. 13) observed that values “are capable of inducing valences that are not a result of the person’s own needs or will . . . . [They] may even command us to perform some activity not in our personal self-interest.” Since values are relational standards, rather than personal possessions, actions answer to values, and can be judged, both by those acting and by others observing. Individuals can criticize themselves or the groups of which they are a part, and work to improve their grasp of the appropriate relationships, or they can learn from the correction of others who have noted their shortcomings. The same is true of groups; they can critique themselves or learn from the challenges of other groups, to strengthen their practices and adjust their goals and rules. Without such standards that transcend sentiment, desire, and norms, genuine learning and development (i.e., getting better) would not be possible (; ; ; ; ).

Although the actions of individuals and the practices of cultures answer to values, there is space and time for considerable variability in realizing values. There is more than one right way to explore France, to converse with a friend, or to advance scientific knowledge, but not all possible ways are equally good, and some may be bad (i.e., sooner or later they will undermine the integrity of the activity). Researchers are often tempted to make strong judgments about the actions of those they study (e.g., doing x is an “error”). However, sometimes this is done without adequate consideration of the larger context of action and its physical, social, and moral complexities (; ; ). The intention of an ecological approach is to be a hedge against such tendencies, while, at the same time, providing resources for taking seriously the necessity of distinctions such as “right/wrong, meaningful/meaningless, beauty/ugliness, good/evil, [and] love/hate” (, p. 544) as crucial ones for psychology as a natural science ().

We now turn to considering examples of how an ecological values account can contribute to improving research and theory in social psychology and perception-action tasks. These two domains were chosen because they are diverse in their topics and methods, and they show how ecological values theory provides fresh insights and generates novel hypotheses.

Coordinating Social Interactions: How Values Expand, Complicate, and Clarify Dynamics

Social psychology has emphasized peoples’ tendencies to conform, to imitate, to mimic, and to obey. However, the available evidence reveals a far more complex and interesting set of dynamics (e.g., ; ; ; ; ). We begin with a reinterpretation of experiments on social influence, which continue to be influential in social anthropology, developmental psychology, biology, robotics, and neuroscience, as well as social psychology (e.g., ; ; ; ; ; ; ). We elaborate this example in more detail than others for two reasons. First, it nicely illustrates the theoretical claims just presented. Second, the fame of Asch’s experiments makes it easy for nearly everyone to think that they understand them better than they do; thus, we will try to show how framing them in terms of values expands, complicates, and clarifies the findings in ways that other accounts do not.

A Dissenting View: Speaking Truth to Power

, asked individuals to answer relatively simple factual questions about line lengths, except on 12 of 18 trials everyone else in a small group of participants (who were confederates) gave the same incorrect answer before it was the individual’s turn to answer. In designing the experiments, expected that participants would always dissent when others gave incorrect answers. This was because he believed he had created an all-or-nothing choice between right and wrong; independence was good, and consensus was “malignant” (, pp. 495–496). Participants should ignore what others said and trust only themselves; their only social obligation was to the experimenter (). Donald , whom thought understood his work better than most, disagreed. He proposed that people in an Asch dilemma should believe that the consensus was correct, but they should report their own personal perspective even though it was probably incorrect. The reason for believing one thing and doing another was a matter of epistemic responsibility; consensus helps to find the truth when people honestly report their individual viewpoints.

Most social psychologists have not followed either Asch’s or Campbell’s line of reasoning; they have shown little or no interest in dissent (e.g., ; ). Their concern has been to explain why people choose to agree with obviously incorrect answers (). Two general approaches have been taken. One is informational influence: people are not sure about the correct answer, despite what they can clearly see, and think it is safer to agree with the consensus. The other is normative influence: people know the correct answer but are afraid to say it for fear of being scorned or ostracized (e.g., ; ), or because they want to ingratiate themselves to others (). More recently, this distinction has been posed in terms of goals; people want to be right and to be liked (). Sticking with the consensus seems an obvious way to gain both goals ().

Asch’s results pose serious challenges for all of these accounts. First, participants dissented two-thirds of the time when there was a unanimous majority, and 95% of the time when the majority was 80% (). These results undermine normative and informational influence accounts, which lead one to assume that agreeing with others is typical (); yet dissent dominates rather than agreement. On the other hand, there is far too much agreement with wrong answers for Asch’s account; his zero-tolerance standard for agreeing with the majority was unrealistic (), and his surprise at his results has contributed to the misrepresentation of his research (; ). Second, the range of responses was extensive, varying from never agreeing with wrong answers (about 25% of participants) at one extreme to disagreeing occasionally and agreeing mostly (about 30%) at the other extreme. Third, 70% of participants dissented most of the time, illustrated by the median participant who dissented nine times and agreed with wrong answers three times. None of the accounts have addressed adequately the diversity of actions taken by participants; and, in particular, they have failed to address the largest and most typical group of participants that form the middle of the distribution (). Fourth, few participants seem to have believed that the majority was correct on critical trials, even when they chose to agree with the majority’s answer (); furthermore, agreement with the majority dropped dramatically when answers were not given publicly to peers (). These findings are troublesome for analysis, as well as the informational influence account.

We have taken the time to review key findings of studies and to summarize three important interpretive frameworks for two reasons. One reason is that Asch’s results have been pervasively and persistently characterized in misleading ways (e.g., ; ; ). The experiments are routinely presented as a powerful example of the strength of conformity, showing people “blindly going along with the group” (, p. 349). The massive amount of dissent is ignored, largely because social psychologists have unwittingly adopted Asch’s zero-tolerance norm for defining conformity (). Dissent and truth-telling have been treated as undeserving of explanation (; ). A second reason is that the interpretive frameworks themselves have often not been well understood. Asch is widely viewed as trying to demonstrate conformity, not challenge it (). view is virtually undiscussed in the conformity literature. The informational and normative accounts were advanced to explain agreement with erroneous answers, but some psychologists assume that the concern for accuracy means trusting oneself (not the consensus), and the concern for acceptance means following the lead of others. This garbles the intended meaning of the distinction; it ends up being a restatement of the normative dilemma (i.e., wanting to give one’s own answer, but fearing the disapproval of others). Neither separately nor together can these approaches account for the full range of the results and the complexity of the situation.

explored an alternative account based on values, which we will try to elaborate and sharpen. Asch’s dilemma is a field of action located within a number of interrelated systems (e.g., perceptual, social, linguistic, and cultural) that is more complex than Asch and others anticipated. Actions are constrained and guided by multiple values that are in tension; these include, among others, truth, social solidarity, justice, and trust. What are these values and how do they work themselves out in this context? Truth seems to be the one value that had in view, but his view of it was simplistic, as more complex view reveals. For Asch, being truthful was simply saying what one sees without regard to others. By contrast, Campbell was aware that truth is social, not just personal; truth requires interdependence, not only independence. An ecological account pushes well beyond Asch and Campbell regarding truth. Participants need to be true to the situation as a whole. There are multiple relationships to which one must be true—one should be true to one’s own perceptual experience, but one must also be true to one’s peers, the experimenter, and those beyond the immediate situation to whom one is accountable (e.g., family; friends; scientific community).

The search for how to be true is constrained by other values. Social solidarity is the obligation to care for the communities of which one is a part, so that they too can realize values. It is not to be confused with or reduced to a desire to belong to a group for the sake of being accepted, liked, or esteemed by others (e.g., belongingness; ). The justice that is called for is for all parties to receive what is their due; that is, justice requires attention to and respect for the experimenter, one’s peers, one’s self, and one’s reference groups (e.g., communities of which one is a part). Finally, trust is essential for knowledge; without it, truth cannot be vouchsafed (). It is also a crucial form of respect, and it contributes to social solidarity. However, it cannot be reduced either to a simple acceptance of others’ claims or to an assumption of one’s own infallibility. Rather, trust is the ongoing activity of using all available resources to determine what leads toward truth and goodness ().

While Asch and Campbell tried to focus truth, the informational and normative influence accounts never really get values in their sights at all. There is no concern for truth as something other than achieving the goal of being correct in one’s answers, and possibly being recognized for being right. If accuracy is reduced to a goal and isolated from other values, it does not add up to truth in this situation (see , for a similar problem in memory research). The normative account takes another potential good, namely being esteemed and belonging to a larger community, but without taking account of the correlative responsibilities of contributing to the well-being of the community, to enhancing its capacities for doing justice, engendering trust, and finding truth. Both informational and normative influence accounts are too individualistic and self-focused to capture the social and moral complexity of Asch’s dilemma.

If it were not for values and the tensions within and between them, there would be no dilemma at all. At first, Asch’s dilemma seems to afford no possible way to realize all of these values. How does one say something that honors the integrity of one’s own perception, demonstrates trust in others, does justice to the experimenter’s question, and is sensitive to the situation in which they all are embedded (i.e., a scientific experiment on perception, which is embedded in much larger ecosystems of community and culture)? On any given item, the only choice allowed by the experimenter’s rules was to agree or disagree with others’ answer. However, if participants engaged in heterarchical shifts, sometimes disagreeing and sometimes agreeing with the majority, they could communicate—awkwardly but effectively—their own views, as well as their respect for others’ differing views. The median pattern of nine dissents and three agreements illustrates this possibility: One makes clear one’s dissent, but occasionally one repeats what others have said to make it apparent that one is aware of their views, and that one intends to treat them as trustworthy partners in understanding the situation in which they all find themselves. The apparent inconsistency of agreeing and disagreeing with others truthfully captures the awkwardness and frustration of the larger situation in which they are located.

This analysis suggests that it is morally and socially appropriate to take others' views seriously, even when one thinks them mistaken, in the hope that continued conversation and exploration might reveal the source of the discrepancies. That is, ecological values theory takes the view that people generally understand that finding truth depends on working together. Rather than identifying with others solely for the sake of safety, participants are acknowledging values to which the group, as well as the individual, must answer. Variations over time can be seen not as inept inconsistency or as lapses in conviction or courage, but as ways of speaking truthfully rather than being overpowered either by consensus or by self-confidence. Rather than being trapped in an all-or-nothing choice, participants can complicate their actions over time to reveal more clearly and comprehensively the situation they are in and the values that define it. proposed that participants were engaging in local errors in order to communicate a larger, deeper truth about the situation. They noted that Asch himself had done the same thing in one sense; in his effort to show the “power” of truth (i.e., that people would dissent from an errant majority; , p. 55), he had designed an experiment that used deception (i.e., confederates giving false answers).

There were collective resources, as well, for Asch’s participants to create more nuanced, global characterizations of the dilemma and the multiple values constraining their actions. Participants could take advantage of their expectations about how others might respond to the dilemma in deciding what they themselves should do. This is brought into sharper relief by observation that there were three distinct peaks (12, 9, and 4 dissents out of 12 possible) in the distribution of , data that can be seen as reflecting three general ways that values can be dynamically balanced in heterarchical fashion as the experiment unfolds. They suggested that the “biological, social, and moral integrity of communities might best be served by the existence of a diversity of strategies that honor the multiplicity of values” (p. 14). Groups are likely to function most adaptively and appropriately over time if members vary how they balance various values in situations as confusing and tense as the Asch dilemma. In such situations, the collective response can do greater justice to the complexity of the situation than any individual’s response.

Claiming that there is no one best way of responding to Asch-like dilemmas is not a recipe for relativism. First, an ecological account rejects the all-or-nothing perspective of Asch and most social psychologists, which accuses participants who agree even a single time (while dissenting 11 times) of having conformed. Second, it suggests that Asch’s participants were not, in all likelihood, either conforming or acting independently. Rather, it is more likely that they were engaging in creative, cooperative action to engage in truth-telling, social solidarity, trusting, and justice. Third, it points to the possible dangers of the pure dissent which admired. Always disagreeing with others runs the risk of communicating an arrogant and dismissive attitude that undermines the possibility of finding consensus. Dissent implicitly appeals to some common ground; without social solidarity and trust, there can be no fruitful dissent. Fourth, epistemic and ethical evaluation of any given individual or group needs to be scaled over time and across tasks, not simply based on isolated, momentary decisions. In all of these ways, and more, ecological values theory differs from accounts that assume people are always self-centered and defensive (e.g., fearful of being wrong, or being different), or accounts that focus only on goals or rules to explain actions.

The dilemma is an example of a frustrated system. It is a challenge to the integrity and flexibility of ecosystem relations, but Asch’s results suggest that the observed variability in participants’ behavior was truthfully capturing the larger tensions of the situation, due to participants’ efforts to realize multiple values, heterarchically related, that emerge as the situation unfolds.

Alignment, Divergence, or Dialogue? How Values Increase Comprehensiveness and Coherence

The values-realizing analysis of the dilemma has implications for many other issues in social coordination, social learning, and social anthropology. We can mention only a few. First, standard approaches to Asch-type situations predict that people will conform more to friends than to strangers (); however, an ecological account predicts the opposite, at least in many truth-telling situations (). Evidence reveals more dissent, not less, among friends (; ; ). Friends can challenge friends more bluntly about errors or dangers because trust and social solidarity are well established (: ). This suggests that the relationship among values is not primarily in terms of tradeoffs; rather, it is cooperative and heterarchical.

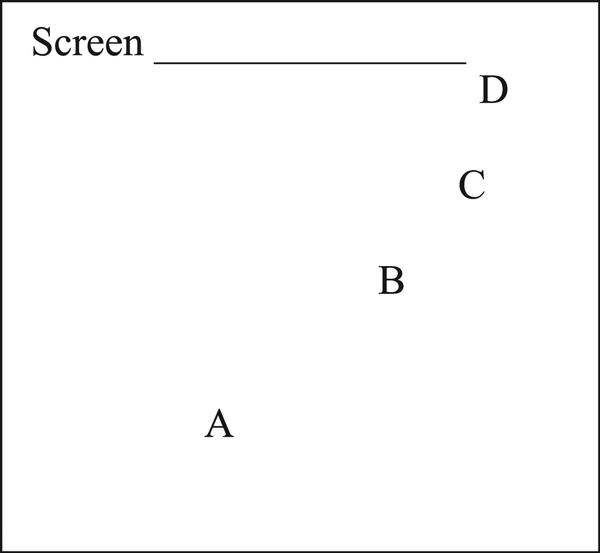

Second, thought he had created a dilemma about truth that invited dissent. What would happen if one were in a similar situation except that it invited agreement with one’s peers? created a situation in which two people (A and B) were in good positions to answer correctly, while a third (D) was not and could only guess (see Figure 1). Would the participant in the position of ignorance follow the lead of A and B when they answered correctly? Hodges et al. made the counterintuitive prediction that participants would intentionally give disagreeing, incorrect answers a significant proportion of the time due to the same sorts of dynamics that led participants in an Asch situation to sometimes give agreeing answers. The hypothesis was confirmed: about 30% of the time participants made up their own wrong answer, a speaking-from-ignorance effect. Participants are in a dilemma much like Campbell’s analysis of Asch: They can say what they believe is correct or they can indicate what they see from their position. They feel obligated to trust others and to speak truthfully, which leads them to sometimes choose to create wrong answers that reveal the larger truth of the situation: that they are in a position of ignorance. When participants were primed to be particularly sensitive to the demands of truthfulness, the frequency of disagreeing, incorrect answers increased, even when there were financial incentives for correct answers. In both the Asch dilemma and the speaking-from-ignorance dilemma, participants sometimes give answers they know are incorrect, so that they can communicate the larger truth of the situation and realize values more fully. People are motivated by more than goals (e.g., to be correct and to be agreeable).

Figure 1

General layout of seating positions in speaking-from-ignorance experiments.

Third, ecological values theory leads one to expect that phenomena such as mimicry, synchrony, conversational alignment, and social learning are likely to reveal dynamics that are similar to those revealed in social dilemmas. Rather than a simple story of convergence, matching, and alignment, a more complex dialogue between convergence and divergence, between alignment and nonalignment, will be found. An ecological values account predicts that these coordinative practices will resist explanation solely in terms of laws, rules, or goals, and will be characterized, not by dominance of one partner in the dialogue, but by heterarchical reversals in which the activities of leading and following are joint and reciprocal. Although much further work is needed, there is considerable evidence in favor of pursuing this line of inquiry (e.g., ).

For example, mimicry is often described as if it were automatic, unintentional, and irresistible (e.g., ); however, research indicates that it is context-dependent and selective (e.g., ). It is dramatically reduced or absent in situations where trust or social solidarity is in doubt (e.g., ; ; ). Synchrony reveals a similar pattern of dynamics (). It is undermined by disagreement or by one of the partners acting irresponsibly in the larger context in which actions need to be coordinated (; ). Engaging in joint action with another requires dialogue, not mirroring (). In spontaneous conversations, participants repeat each other’s syntactic constructions less often than expected by chance (), and partners often create linguistic conventions on the fly that are idiosyncratic and flexible, becoming more complementary than convergent over time (). Overall, it appears that selective alignment yields better joint actions (e.g., greater accuracy in a coordinative task) than indiscriminate alignment (). In all these cases, an ecological values-realizing account encourages moving to a higher, more dialogical, level of dynamics rather than focusing only on convergence/matching on the one hand, or divergence/asymmetry on the other.

Research on social learning paints a similar picture. Theorists in social anthropology believe humans’ tendency to follow the lead of other humans is very strong, especially compared to other apes (e.g., ; ). However, people often lean on their own experience rather than adopting technologies and methods most frequently used by others (e.g., ; ; ). People are particularly unlikely to move to majority options when they are motivated to be accurate (), and some theorists have claimed that a conformity bias cannot function as a stable adaptive strategy ().

Research on social learning in children also points beyond conformity and toward values-realizing dynamics. Children are often viewed as easily influenced, gullible even, yet many recent studies show how committed to truth children are, and how sophisticated they are about who to trust, and when, in assessing others’ claims and actions (see , , for reviews). They take truth, justice, social solidarity, and trust into account in ways that have remarkable integrity and flexibility, even by adult standards. Two studies placed children in Asch-type dilemmas and found that young children overwhelmingly dissented—most of them, every time—although the authors chose to emphasize the minority of agreeing answers (; ). Similarly, on practical action tasks (e.g., opening a puzzle box) preschoolers mostly do not adopt the consensus view or procedure when it is unsuccessful or implausible, even when they identify themselves as part of the group (; ). However, children are also sensitive to social solidarity and trust (e.g., ). Children and adults show flexibility and sensitivity in how they learn from others; they engage dialogically with others and with their surroundings to realize values.

Methodologically, ecological values theory predicts that similar patterns of convergence–divergence, symmetry–asymmetry, and stability–flexibility will emerge across a wide array of social coordination tasks if researchers can enlarge their explanatory canvas while noticing details of actions more closely (). Ways this can be done include (1) looking carefully for signs of selectivity and context-dependency in their phenomena (e.g., ; ); (2) integrating findings from across various social coordination domains, rather than remaining in research silos (e.g., ; ); and (3) acknowledging the time dimension in research and moving questions and analyses to higher level dynamics that are dialogical rather than focusing only on convergence/matching on the one hand, or divergence/asymmetry on the other (e.g., ; ). To give one example of the surprises in store, consider that social psychologists generally treat conformity in individualistic terms and see it as a danger; by contrast, social anthropologists treat it in terms of collective patterns and see it as an essential aspect of cultural evolution (). Ecological values theory suggests that both of these stories are too simple; putting them in dialogue will likely yield a richer, truer account.

Acting and Perceiving: How Values Increase the Integrity and Flexibility of Skills

Researchers have often looked to dramatic dilemmas or difficult choices to study values. This is quite reasonable, but values are also revealed in mundane, everyday acts such as walking, carrying, and driving.

Driving for More Than Accuracy

Driving was used earlier to illustrate the necessity of values, but how does paying attention to values affect the actual conduct of research? One of the most common weaknesses of many studies of driving and related sorts of skills has been an excessive focus on a single value, treating it as if it were a goal (). For example, how accurately can a driver stop a vehicle from a designated target, such as another car? Often, in such conditions, there is precise optical information that specifies time-to-contact (TTC; ; ); thus, drivers should be able to make highly accurate judgments. However, drivers persistently underestimate TTC and often women do so even more than men, both of which researchers have struggled to explain (e.g., ; ; ). If there are natural laws that provide the right information for acting appropriately, why do drivers’ actions not reflect that fact ()?

From the perspective of values-realizing, claims that males are more accurate than females (e.g., ) could just as easily have been described as “females are safer than males.” Seeing how close one can come to a stopped vehicle may be more accurate, but it is also less safe (). Likewise, sensitivity to safety can also explain why TTC is usually underestimated: “Erring on the safe side” will generally lead to much better driving than “cutting it as close as possible.” Drivers also take into account their own abilities and proclivities in making TTC judgments. Older drivers tend to underestimate TTC more than other drivers, as do drivers who have impaired vision (e.g., ). Although all of these can be interpreted as supporting the importance of safety in action, researchers find it difficult not to equate inaccuracy with a reduction in safety, even when the observed biases would generally contribute to safer driving (; ). From an ecological perspective, attending to only one value, as if it were a goal, leads to bad driving; the same is true of research that treats one value (e.g., accuracy) simply as a means to another (e.g., safety). Focusing only on goals, whatever the activity, neglects the heterarchical, frustrated nature of value-realizing action.

Working within an ecological framework, has shown that even when a single dimension of driving (i.e., braking) is chosen and the experimental task focuses on a single value (i.e., accuracy), there are many other constraints that guide online control of action. The methodological move that opened a larger space for understanding various aspects of driving was to introduce many more variables into the “braking equation” than are usually included in driving experiments. This increased variability stresses the driving ecosystem; however, these increased demands also help to reveal the diversity of values that enable and guide driving. For example, even if drivers are not told about a sudden change in brake strength or dynamics, they quickly recalibrate their actions in light of what they pick up from optical variables, making appropriate alterations to their pedal behavior (, ). Drivers’ selection of actions and ongoing control of them are not determined by any one value in a way that can be designated as a “law of control.” “There is no such thing as a preferred state in which the actor should strive to be at each point in time” (, p. 406), which suggests that driving is not exclusively a goal-oriented or rule-following task; instead, it is characterized by an ongoing state of tension among many values.

Some artificial intelligence researchers have explicitly argued that autonomous driving systems will require value-based argumentation rather than following fixed rules, if they are to be functional in the complexity of open environments (e.g., ). Whether that will be possible remains unknown. In any event, narrow-gauge approaches to driving can easily miss the complexity and richness of the skill, generating experimental anomalies and practical puzzles. Locating driving in a larger ecology of values can help to avoid such oversimplifications.

Carrying: Beyond Goals and Rules

Dozens of times during a day people thoughtlessly or deliberately pick up some item and move it from one place to another. In either case, carrying is an intentional act. It is to see where something is, and then to transport it to a place where it ought better to be; thus, carrying is a values-realizing action. The act of carrying is ordinarily intended to increase safety, justice, freedom, beauty, or other values (although it does not always succeed). Frequently, carrying is goal-directed, but the motivation and justification for any move or set of moves depends on values, not just goals.

Carrying is a physical act, and thus, it is not surprising that weight affects the dynamics of lifting and carrying. Heavier weights require different movements than lighter weights, and those differences can be perceived by observers who can see only point-light (kinematic) displays of limb movements. Even when those carrying the load are instructed to engage in deceptive action, trying to make a heavy weight appear light or vice versa, properly attuned perceivers can identify to some extent both the true weight and the deceptive intent (), even when skilled actors and mimes are employed (). proposed that moral and social relationships would alter kinematic patterns of people carrying items in physical tasks that were challenging. Parents carried their child, or an equally weighted sack of groceries or trash across a series of uneven steps with gaps between them, holding them in the same way. Observers who saw point-light films of parents’ movements alone, with no knowledge of anything being carried, rated child trials as being more careful than groceries and trash trials. These results suggested that moral obligations of parents to children altered their carrying movements in ways identified as being more careful. Many values constrain walking and carrying, among them comfort, speed, safety, accuracy, stability, variability, and even social solidarity (e.g., parent carrying their child). Research that focuses only on measures of energy consumption (e.g., comfort) or stability are likely to be too limited to be adequate.

One important question that emerged from this research was: What variations in movement patterns indicate that one is acting carefully? Neither psychology nor kinesiology has addressed this question directly. Existing studies have focused on safety and stability, often defined in terms of the goal of “not falling” (; ). Whatever safe, stable walking is, it is unlikely to capture the meaning of carefulness because it does not address the nature of what is being carried and how it is cared for as it is being carried. Almost certainly, it will require dexterity, the capacity to generate novel action patterns that adaptively address situational demands as they emerge in real-time (; ) as well. Values constraining careful carrying are not located only in the object carried, or in the steps, or in the parent, or in walking per se; rather values are distributed across the relationships that make up the ecosystem. It is important to note that the heterarchical nature of values means that children will not always be carried more carefully than groceries or other items, although virtually all parents indicate that they believe that their child is more valuable. There are variations between tasks, between moments within tasks, and there are individual differences among parents as well. For example, a child carried frequently, and who cooperates in being carried, may produce kinematic patterns that are rated as less careful than “dead weight” (e.g., groceries) carried infrequently. However, at any moment in the stepping, a disturbance can require a sudden change in the dynamics, reasserting the priority of safety over comfort, or accuracy over freedom. Although available evidence is limited, it favors ecological value theory’s claims: that values are not localized; that there is not a fixed hierarchy of constraints; and that conscious intentions and awareness are not sufficient to characterize the values constraining actions ().

Finally, we consider recent, influential research on carrying to illustrate how attending to the broader, value-realizing context of actions can clarify and contextualize studies framed only in terms of goals, rules, and laws. presented participants with a simple, two-part goal task: Walk down a pathway which had pails stationed alongside, reach and pick up a pail with its contents, and carry it to a target destination. Besides varying in weight, pails were positioned closer to or farther from the target destination and on the right or left side of the pathway. The key rule was to do “whatever is easier.” Invoking “law” that actions requiring less effort are preferred unless there are rewards that make the greater effort worth it (), Rosenbaum et al. expected participants to pick up the pail closest to the target destination, since that would mean the carrying action would be shorter (thus, less effortful). However, participants mostly did the reverse. To explain this “suboptimal” action, they proposed a post-hoc hypothesis framed in terms of goals; participants wanted to achieve a sub-goal (i.e., picking up a pail) of the larger goal task as quickly as possible rather than waiting to pick it up.

An ecological values account approaches the situation differently. Researchers (; ) began their research assuming that one value (i.e., comfort), treated as a goal (do what is “easier”), would yield a lawful outcome (i.e., Hull’s least effort principle). When that did not work out as planned, they adopted another isolated value (i.e., speed) as a goal, treating it as fundamental (i.e., do part one of the task as quickly as possible).

In doing so, they traded one value for another. However, their results indicate that neither of these values is the fundamental constraint; sometimes, participants chose to carry heavier weights farther; other times, participants picked up weights later rather than sooner (). The ecological claim is that there is no one fundamental constraint. If loads were heavier and the walking distance was longer, comfort (effort) would likely become a much more prominent constraint than doing a sub-goal task sooner rather than later. If the load being carried were more important (e.g., a child), it is not likely that comfort or the desire to get started sooner rather than later would weigh heavily in action choices and persistence. A methodological implication of this analysis is that researchers need to stress ecosystem relations more in order to discover the diversity of constraints that are relevant, and to pay close attention to the diversity of actions that occur within and across tasks.

Prospects and Challenges

A fundamental conviction of ecological values theory is that all psychological acts are constrained and guided by multiple values that cannot be reduced to a common scale. In this article, we have not offered a definitive list of values or proposed some universal structure to be applied to all situations. Attempts to characterize all action and cognition with a single common motivation (e.g., expected utility) or a set of universal concerns or motives (e.g., benevolence; achievement; hedonism; pathogen avoidance; mate selection) end up shortchanging the diversity and complexity of ecosystems, and the selectivity, directedness, and organization of collective and individual actions within those systems. Rather, we believe a crucial question for researchers to address is: What values are, in fact, constraining (i.e., enabling and guiding) actions in any given context? In this respect, an ecological values-realizing account is in no different position than accounts framed in terms of laws, rules, or goals. It is up to researchers to make the case that they can identify relevant laws, rules, or goals that illuminate particular situations and phenomena. The same is true of values.

A more specific example is provided by the history of how reinforcement as an explanatory concept has been understood. Originally, it was assumed that there was some definable list of primary reinforcers and secondary ones that had become associated by temporal contiguity and which had trans-situational effects (). Later this gave way to the Premack principle, which proposed higher probability activities served as reinforcers for lower probability activities (). Still later, it became clear that the relationship was heterarchical; almost any activity could serve to reinforce another activity, or vice versa. What mattered was their prior relationship and how that had been disturbed; activities that had been restricted could reinforce unrestricted ones. The central motivation of individuals’ actions was maintaining their freedom to engage in an optimal distribution of activities (e.g., ; ). In short, reinforcement turned out to be about a complex set of relationships; it was not a set of items, but a matter of ecological relations over time. Our argument is that values, too, are best understood in terms of ecological relationships, rather than as “things” located in individuals, groups, or environmental objects.

The difference between values and reinforcements is that the latter are determined in terms of personal preferences regarding what is more and less pleasant, while the former includes but is not limited to what is pleasant, comfortable, or desirable. Values demand that pleasure take its place among many other values and exist in tension with them. However, even if one considers the value of pleasure alone, there are multiple pleasures that must be selected and ordered (or organized) in some way, such that what counts as reinforcement is a relational matter (; ).

One of the most telling weaknesses identified in the various studies we discussed earlier was a tendency to focus on a single value, which was then treated as a goal to be achieved. In other cases, one part of a dialogical relation (e.g., convergence/divergence) was highlighted while its complement was not. Given this tendency, researchers often identify values-realizing actions as errors, failures, or biases, when a larger, ecological understanding suggests otherwise. Similarly, actions that seem sensible when viewed narrowly (e.g., being as accurate as possible) prove to be problematic when placed in a longer time frame and in a collective field of action (e.g., driving; truth-finding).

Ecological values theory also claims that the relation among values constraining action is heterarchical. This militates against the common notion that values are scaled by their importance, yielding a determinate hierarchy or a fixed set of tradeoffs. Any one value can be realized best when it is supported by all the other values. If this is correct, the methodological implications are that experimenters would do well not to believe, a priori, that they know all the important constraints that define some task or ecosystem. It encourages researchers to place goal-directed actions in larger, more complex, values-realizing contexts, rather than trying to isolate supposed components of the skill, which are tested independently. Making accuracy a goal, for example, which many studies do, may undermine its achievement ().

Values have an intrinsic developmental dimension; that is, values reveal themselves over time. The heterarchical interdependence of values creates an intrinsic dynamic that motivates ongoing change that is both directed and open-ended. From the perspective of theories that want to privilege stability, invariance, and control, the openness and flexibility of values may make them appear to be weaker explanatory options than lawful invariants or rule-governed patterns. The research we have reviewed suggests otherwise. Values prove more resilient than rules and laws for explaining actions over time.

Furthermore, values are distributed across the dynamics of ecosystems, rather than being located in any one of their components. Values cannot be reduced to moral ideals, or social norms, or physical laws; rather, values are ecosystem defining goods that supersede all of these. As a consequence, one of the crucial ways in which values can be revealed is by stressing the ecosystem relations in one or more ways. Increasing weights, distances, and tensions across social, moral, and physical dimensions allows boundary conditions of various tasks to be revealed more comprehensively and clearly.

If ecological values theory has merit, then it is reasonable that it will prove useful in other domains, such as development (; ), language (, ), reasoning (), and emotion (). One question that is likely to emerge in all of these contexts is, how does values-realizing activity vary across cultures and between individuals within a culture? In general, the question of variability that occurs across space (e.g., culture and individuals) and time (e.g., development) is not unlike the variability that occurs in the moment-to-moment shifts within an activity such as driving. Values push back on cultural preferences and individual desires, inviting criticism, creativity, and growth. However, values-realizing action is always specific to particular places, moments, groups, and individuals.

Values-realizing activity raises compelling and difficult questions about human agency and action that have challenged scientists and philosophers (e.g., ; ; ). One such question is the relation between values, laws, rules, and goals. We considered this briefly, but much further work is needed. Another question is the relation of values and facts, and how the two are properly understood and related to each other (e.g., ; ). Some worry that scientists will be tempted to overreach, claiming to know what people ought to do (); others worry that ethical obligation will be reduced to the injunction to do whatever one naturally feels inclined to do (). Neither of these real dangers is a necessary consequence of taking values seriously. In fact, the various research examples we presented earlier indicate that, far from endangering science and ethics, taking values seriously provides new insights and fresh possibilities to explore.

An important clarification that we did not address while discussing various studies was that people are ordinarily not aware of the values guiding their actions. Patterns of behavior can vary in systematic and dynamic ways with almost no conscious recognition by those acting. Participants in an Asch dilemma would be very unlikely to articulate the pragmatic constraints on what they chose to say (; ). Values that guide action are largely tacit, at least at the time of action (). People often are embarrassed by social psychologists who demonstrate that their actions are influenced by factors that do not serve as good reasons for engaging in an action (e.g., the candidate they voted for was taller, or was at the top of the list of candidates). However, point out that people often do the reverse; they engage in socially sensitive and morally responsible actions with virtually no awareness of the normative considerations that shaped their choices and their actions (). Whether driving or conversing, people often shape their actions to be more just, kind, and cooperative than might be thought necessary; they are thoughtlessly “thoughtful.”

On the other hand, people can be remarkably careless, cruel, and dishonest (e.g., ). Values are embodied markers of one of the deepest mysteries of existence, good and evil; nevertheless, judgments about oneself and others are an essential dimension of human interaction and cognition (), and actions and emotions are evaluative in fundamental ways (; ).

There are, of course, many other questions that deserve attention. If values are so important, why have they not been emphasized more by psychologists? A partial answer is that values are often recognized, at least implicitly, but are taken for granted. In other cases, values are ignored or are framed, not as values, but as goals or rules. This reflects a general tendency across the sciences to choose smaller units of analysis or more local circumstances to frame research questions and methods; however, increasingly, scientists have learned the need for paying attention to larger and longer spatial–temporal scales ().

Realizing values is an ongoing project. We have tried to show that values are part of the fabric of everyday action and interaction. How scientists might best conceptualize values and explore their relation to action is a daunting challenge, but one well worth the effort. It is dubious that agreement will ever be complete, but then that is as it should be. Without dissenting voices, it is far too easy to be complacent.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper provided by Alan Costall, Laura Cuijpers, Adrian Frazier, Martin Fultot, Jonathan Gerber, Jason Gordon, Henry Harrison, Steven Harrison, Keith Holyoak, Blair Johnson, Maria Jarymowicz, Wim Pouw, Janusz Reykowski, Vasudevi Reddy, Nicole Rossmanith, and the reviewers of this journal. The article is dedicated to the memory of James E. Martin.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Joanna Rączaszek-Leonardi was funded by Grant NCN Opus 15 2018/29/B/HS1/00884.

References

- Achourioti T., Fugard A., Stenning K. (2011). Throwing the normative baby out with the prescriptivist bathwater. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34(5), 249.

- Allen V. L. (1965). Situational factors in conformity. In Berkowitz L. (Ed), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 133–175). Cambridge, MA: Academic Press.

- Allison J. (1989). The nature of reinforcement. In Klein S. B., Mowrer R. R. (Eds), Contemporary learning theories: Instrumental conditioning and the impact of biological constraints on learning (pp. 13–39). Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Anderson M. L. (2015). Beyond componential constitution in the brain: Starburst amacrine cells and enabling constraints. In Metzinger T., Windt J. M. (Eds), Open MIND: 1(T). Bengaluru, Karnataka: MIND Group.

- Asch S. E. (1951). Effects of group pressure upon the modification and distortion of judgments. In Guetzkow H. (Ed), Groups, leadership, and men (pp. 177–190). Pittsburgh, PA: Carnegie Press.

- Asch S. E. (1952). Social psychology. Hoboken, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

- Asch S. E. (1956). Studies of independence and conformity: I. A minority of one against a unanimous majority. Psychological Monographs, 70(9). 416.

- Asch S. E. (1968). Gestalt theory. In Sills D. L. (Ed), International encyclopedia of the social sciences (pp. 158–175). New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Asch S. E. (1990). Comments on D T Campbell’s chapter. In Rock I. (Ed), The legacy of Solomon Asch: Essays in cognition and social psychology (pp. 53–55). Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Beek P. J., Turvey M. T., Schmidt R. C. (1992). Autonomous and nonautonomous dynamics of coordinated rhythmic movements. Ecological Psychology, 4(2), 65–95.

- Bench-Capon T., Modgil S. (2017). Norms and value based reasoning: Justifying compliance and violation. Artificial Intelligence and Law, 25(1), 29–64.

- Bernstein N. A (1996). On dexterity and its development. In Latash M., Turvey M. T. (Eds), Dexterity and its development (pp. 3–244). Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Bond R., Smith P. B. (1996). Culture and conformity: A meta-analysis of studies using Asch’s (1952b, 1956) line judgment task. Psychological Bulletin, 119(1), 111–137.

- Brentano F. (1902). The origin of our knowledge of right and wrong. Glasgow, United Kingdom: Good Press.

- Brinkmann S. (2009). Facts, values, and the naturalistic fallacy in psychology. New Ideas in Psychology, 27(1), 1–17.

- Brinkmann S. (2011). Psychology as a moral science: Perspectives on normativity. Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

- Brosch T., Sander D. (2016). Handbook of value: Perspectives from economics, neuroscience, philosophy, psychology and sociology. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

- Bruijn S. M., Meijer O. G., Beek P. J., van Dieën J. H. (2013). Assessing the stability of human locomotion: A review of current measures. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 10(83), 20120999.

- Caird J. K., Hancock P. A. (1994). The perception of arrival time for different oncoming vehicles at an intersection. Ecological Psychology, 6(2), 83–109.

- Campbell D. T. (1990). Asch’s moral epistemology for socially shared knowledge. In Rock I. (Ed), The legacy of Solomon Asch: Essays in cognition and social psychology (pp. 39–52). Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Campbell J. D., Fairey P. J. (1989). Informational and normative routes to conformity: The effect of faction size as a function of norm extremity and attention to the stimulus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(3), 457–468.

- Carello C., Turvey M. T. (1991). Ecological units of analysis and baseball’s ‘illusions’. In Hoffman R. R., Palermo d. S. (Eds), Cognition and the symbolic processes: Applied and ecological perspectives (pp. 371–385). Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Ceraso J., Gruber H., Rock I. (1990). On Solomon Asch. In Rock I. (Ed), The legacy of Solomon Asch: Essays in cognition and social psychology (pp. 3–19). Oxfordshire, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- Chartrand T. L., Lakin J. L. (2013). The antecedents and consequences of human behavioral mimicry. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 285–308.

- Cialdini R. B., Goldstein N. J. (2004). Social influence: Compliance and conformity. Annual Review of Psychology, 55, 591–621.

- Cialdini R. B., Trost M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity and compliance. In Gilbert D. T., Fiske S. T., Lindzey G. (Eds), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 151–192). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Claidière N., Whiten A. (2012). Integrating the study of conformity and culture in humans and nonhuman animals. Psychological Bulletin, 138(1), 126–145.

- Corriveau K. H., Fusaro M., Harris P. L. (2009). Going with the flow: Preschoolers prefer nondissenters as informants. Psychological Science, 20(3), 372–377.

- Corriveau K. H., Harris P. L. (2010). Preschoolers (sometimes) defer to the majority in making simple perceptual judgments. Developmental Psychology, 46(2), 437–445.

- Costall A. (1989). A closer look at direct perception. In Gellatly A., Rogers D., Sloboda J. A. (Eds), Cognition and social worlds (pp. 10–21). Oxford United Kingdom: Clarendon Press.

- Costall A. (1995). Socializing affordances. Theory & Psychology, 5(4), 467–481.

- Darley J. M., Shultz T. R. (1990). The moral judgments of children—and of adults. Annual Review of Psychology, 41, 525–556.

- De Jaegher H., Di Paolo E. (2007). Participatory sense-making: An enactive approach to social cognition. Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences, 6(4), 485–507.

- de Jong H. L. (1991). Intentionality and the ecological approach. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 21(1), 91–109.

- De Rivera J. (1989). Choice of emotion and ideal development. In Cirillo L., Kaplan B., Wapner S. (Eds), Emotions in ideal human development (pp. 7–34). Oxford, United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

- de Wit M. M., van der Kamp J., Withagen R. (2015). Visual illusions and direct perception: Elaborating on Gibson's insights. New Ideas in Psychology, 36, 1–9.

- Deacon T. W. (2012). Incomplete nature: How mind emerged from matter. New York, NY: Norton.

- Deutsch M., Gerard H. B. (1955). A study of normative and informational social influences upon individual judgment. The Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 51(3), 629–636.

- Dewey J. (1976). Human nature and conduct. In Boydston J. A. (Ed), The middle works, 1899–1924. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University Press.

- Douglas K. M., Sutton R. M. (2003). Effects of communication goals and expectancies on language abstraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 682–696.

- Efferson C., Lalive R., Richerson P. J., McElreath R., Lubell M. (2008). Conformists and mavericks: The empirics of frequency-dependent cultural transmission. Economics and Human Biology, 29(1), 56–64.

- Ellis R. D. (2018). The moral psychology of internal conflict: Value, meaning, and the enactive mind. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.

- Elqayam S., Evans J. S. B. T. (2011). Subtracting “ought” from “is”: Descriptivism versus normativism in the study of human thinking. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34(5), 233–248.

- Enesco I., Sebastián-Enesco C., Guerrero S., Quan S., Garijo S. (2016). What makes children defy majorities? The role of dissenters in Chinese and Spanish preschoolers’ social judgments. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1695.

- Eriksson K., Enquist M., Ghirlanda S. (2007). Critical points in current theory of conformist social learning. Journal of Evolutionary Psychology, 5(1), 67–87.

- Fajen B. R. (2007a). Affordance-based control of visually guided action. Ecological Psychology, 19(4), 383–410.

- Fajen B. R. (2007b). Rapid recalibration based on optic flow in visually guided actions. Experimental Brain Research, 183(1), 61–74.

- Fajen B. R. (2008a). Learning novel mappings from optic flow to the control of action. Journal of Vision, 8(11), 12.

- Fajen B. R. (2008b). Perceptual learning and the visual control of braking. Perception & Psychophysics, 70(6), 1117–1129.

- Friend R., Rafferty Y., Bramel D. (1990). A puzzling misinterpretation of the Asch “conformity” study. European Journal of Social Psychology, 20(1), 29–44.

- Frondizi R. (1963). What is value? An introduction to axiology. Chicago, IL: Open Court.

- Fusaroli R., Bahrami B., Olsen K., Roepstorff A., Rees G., Frith C., Tylén K. (2012). Coming to terms: Quantifying the benefits of linguistic coordination. Psychological Science, 23(8), 931–939.

- Fusaroli R., Rączaszek-Leonardi J., Tylén K. (2014). Dialog as interpersonal synergy. New Ideas in Psychology, 32, 147–157.

- Gavrilets S., Richerson P. J. (2017). Collective action and the evolution of social norm internalization. Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences, United States, 114(23), 6068–6073.

- Gee J. P. (1999). An introduction to discourse analysis: Theory and method. Oxfordshire United Kingdom: Routledge.

- Gibson J. J. (1950). The implications of learning theory for social psychology. In Miller J. G. (Ed), Experiments in social process: A symposium on social psychology (pp. 149–167). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Gibson J. J. (1966). The senses considered as perceptual systems. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Gibson J. J. (1979). The ecological approach to visual perception. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

- Goodnow J. J. (1988). Children’s household work: Its nature and functions. Psychological Bulletin, 103(1), 5–26.

- Hahn U. (2011). Why rational norms are indispensable. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 34(5), 257–258.

- Hamacher D., Singh N. B., Van Dieën J. H., Heller M. O., Taylor W. R. (2011). Kinematic measures for assessing gait stability in elderly individuals: A systematic review. Journal of The Royal Society Interface, 8(65), 1682–1698.

- Hancock P. A., Manser M. P. (1997). Time-to-contact: More than tau alone. Ecological Psychology, 9(4), 265–297.

- Harris R. P. (1985). Asch’s data and the ‘Asch effect’: A critical note. British Journal of Social Psychology, 24(3), 229–230.

- Harrison S. J., Stergiou N. (2015). Complex adaptive behavior and dexterous action. Nonlinear Dynamics, Psychology, and Life Sciences, 19(4), 345–394.

- Harrison H. S., Turvey M. T., Frank T. D. (2016). Affordance-based perception-action dynamics: A model of visually guided braking. Psychological Review, 123(3), 305–323.

- Haun D. B. M., Rekers Y., Tomasello M. (2014). Children conform to the behavior of peers; other great apes stick with what they know. Psychological Science, 25(12), 2160–2167.

- Haun D. B. M., Tomasello M. (2011). Conformity to peer pressure in preschool children. Child Development, 82(6), 1759–1767.

- Healey P. G., Purver M., Howes C. (2014). Divergence in dialogue. Plos One, 9(2), e98598.

- Heft H. (1989). Affordances and the body: An intentional analysis of Gibson’s ecological approach to visual perception. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 19(1), 1–30.

- Heft H. (1993). A methodological note on overestimates of reaching distance: Distinguishing between perceptual and analytical judgments. Ecological Psychology, 5(3), 255–271.

- Heft H. (2001). Ecological psychology in context: James Gibson, Roger barker, and the legacy of William james’s radical empiricism. East Sussex, United Kingdom: Psychology Press.

- Heider F. (1958). The psychology of interpersonal relations. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Hermes J., Behne T., Bich A. E., Thielert C., Rakoczy H. (2018). Children’s selective trust decisions: Rational competence and limiting performance factors. Developmental Science, 21(2), e12527.

- Higgins E. T. (2007). Value. In Kruglanski A. W., Higgins E. T. (Eds), Social psychology: Handbook of basic principles (2nd ed., pp. 454–472). New York, NY: Guilford.

- Hirsch J. L., Clark M. S. (2019). Multiple paths to belonging that we should study together. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 14(2), 238–255.

- Hitlin S., Piliavin J. A. (2004). Values: Reviving a dormant concept. Annual Review of Sociology, 30, 359–393.

- Hodges B. H. (2004). Asch and the balance of values. The Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27(3), 343–344.