What factors influence the emergence and development of academic disciplines? While philosophy of science traditionally seeks to answer this question by highlighting the construction, application, and evaluation of scientific theories and methods, historians of science tend to emphasize the importance of cultural, social, political, economic, and other factors that facilitate or hinder the development of scientific knowledge and networks (; ; ). In line with this contextualized perspective, this article aims to highlight an element that has received very little attention so far in the historiography of psychology: The role of student demands and preferences in the shaping of the discipline. Focusing on the German context, I aim to show that this factor had a profound influence on the development of academic psychology through the 20th century, gradually turning it from a small, predominantly male and research-oriented network of academics into a female-dominated clinical profession with more than 100,000 students.

My analysis is motivated by recent events: In November 2019, the German Bundestag passed a new law concerning the training of psychotherapists. As of September 2020, candidates for psychotherapeutic training are required to complete a set of courses and clinical internships at Bachelor’s and Master’s levels in order to obtain their license to practice as a therapist (“Approbation”). After five more years of specialized practical training, graduates are then allowed to run their own practice covered by health insurance. Even though the new psychotherapy law does not define which faculties should implement the new regulations, developments have taken a clear direction: Despite the considerable bureaucratic and financial effort required, 54 out of 59 Psychological Institutes in German universities adapted their curricula to conform to the new regulation by 2023 (). Members of the psychological and psychotherapeutic community have differed considerably in their assessment of this development: Leading representatives of the German Psychological Association celebrated the reform as a “great success,” consolidating psychology “as the mother science of psychotherapy” (, p. 2) and providing an “incredible opportunity” to “further professionalize the discipline” (, p. 101). Others expressed concern, arguing that the diversity of psychotherapeutic schools might be endangered since behavioral therapy, including the “second wave” of cognitive behavioral therapy, has dominated the Faculties of Psychology since the 1970s (; ; ), and also warned that the expansion of clinical subjects comes at the expense of basic and experimental subjects (, ; ). Whether one sees a historic opportunity or an imminent threat to the integrity of the discipline, the question remains as to how it came to this in the first place. Anyone familiar with the history of German psychology, which was founded as a purely theoretical and experimental discipline, may wonder why major parts of the discipline have shifted towards a clinical profession, and which internal and external factors have contributed to this metamorphosis.

By considering these recent developments as the latest stage of a long-term transformation of the discipline, I aim to shed light on the current state of German psychology from a historical and contextualizing perspective, and to inform an international audience about developments that have received little attention outside the German-speaking world. Based on selected publications from academic psychologists and students, historical analyses, assessments from historical actors, and demographic data, I aim to highlight the long-term impact of broad societal dynamics that have shaped the discipline’s growth and development. Starting out in the late 19th century, the psychological field represented first and foremost a growing network of academics conducting experimental and theoretical research. Until the late 1930s, applied psychology grew mostly outside of the university and only few psychologists had any points of contact with clinical practice. The Second World War not only facilitated a significant increase in the demand for practical psychology, but also paved the way for a new convergence between psychology and psychotherapy, generating increased interest in therapy among graduates from the psychological field. As these early points of contact between academic psychology and therapeutic practice were consolidated after the war, the number of psychology students also continuously increased in West Germany, especially among female students. The chronic lack of physicians with psychotherapeutic training and the popularization of psychological knowledge further increased the influx of students and practitioners into the clinical field in West Germany during the 1970s, despite the lack of clear legal regulations governing of their work. In 1999, psychology was finally established by law as an official prerequisite for psychotherapeutic training. The introduction of a European-wide education system after the turn of the millennium increased student mobility across Europe, while private universities entered the German higher education sector. The number of psychology students in Germany more than tripled over the following twenty years and reached the record number of 100,000 students in 2020. After providing a historical overview of the major landmarks that have led to this point, I discuss the dilemmas and challenges that the discipline faces today as a result.

The Founding Years of Applied Psychology in Germany (1903–1933)

With ten psychological institutes at public universities at the end of the 19th century (, p. 413), Germany became the hotbed of experimental psychology during the founding years of the discipline. The pioneering role of German psychology was based on its image as an innovative field of research that combined centuries-old philosophical questions about the human soul with methods and apparatus borrowed from the physiological laboratory (; ). Training professionals was not an integral part of this program, and Wilhelm Wundt even warned against the “premature pursuit of practical applications” (, p. 47) before psychology gained a solid theoretical and methodological foundation. Following the Humboldt Model of higher education, academic psychology offered training for research specialists, and the only official academic title students could obtain was a doctorate. Teachers and students were almost exclusively male, with the first female student to obtain a doctorate of psychology in Germany being the British national Beatrice Edgell, who graduated in 1902 from the University of Würzburg ().

The outbreak of the First World War brought an abrupt halt to the first phase of institutional growth and transnational expansion of German academic psychology. While international exchange was severely hindered, new opportunities for practically oriented psychologists appeared. Like many other European countries, Germany implemented psychological methods in its military for the selection of drivers, pilots, artillerymen, radio operators, and other specialists (; ). After the war, the rebuilding of public infrastructure and the industry brought new opportunities for psychological practitioners. Wherever qualified personnel needed to be recruited and trained, there was a demand for ways to identify suitable applicants. Germany soon became a leader in the field of applied psychology, counting more than 250 “psychotechnical” institutes by the mid-1920s (; ). Despite the growing demand for using psychological methods to select workers, the training of applied psychologists did not take place in universities: Only two out of 23 psychological institutes at German universities offered psychotechnics courses by the mid-1920s, while all 14 institutes devoted exclusively to applied psychology were located at Technical Colleges (, pp. 82-82), where the rise of applied psychology created new opportunities for the first generation of female professors of psychology such as Maria Schorn and Hildegart Hetzer ().

While psychological expertise expanded in the military, industry, and the educational sector, psychotherapy remained the province of physicians until World War II in Germany. Psychotherapy was mostly provided in private practice and was not regularly covered by social security. While some private institutions, such as the Berlin Psychoanalytic Institute, also offered psychotherapeutic training for nonmedical “laypersons,” the vast majority of psychotherapists were physicians with a specialization in psychiatry or neurology (). The boundaries between German academic psychology and medicine were clear: While psychologists were recognized as experts in experimentation and testing, they were not expected to offer any clinical expertise. Despite international recognition of their innovative research and increasing use of psychological practices in personnel selection, German academic psychologists remained a small group until World War II, one housed, moreover, in faculties of philosophy.

The Professionalization and Mobilization of Psychology and Psychotherapy during World War II

After the first wave of expulsion and repression of Jewish, Social Democratic or Communist citizens during the “seizure of power” in 1933, psychology and psychotherapy both went through a phase of accelerated transformation under Nazi rule. With the reintroduction of conscription in 1935, German military psychology soon became the largest employer of (male) psychologists: , p. 161) estimates that the number of psychologists in the Wehrmacht peaked at about 450 in 1942, compared to only 33 in 1933. As in World War I, the main task for psychologists in the military was the selection of suitable candidates for different areas of military training. Here however, the lack of a uniform teaching curriculum among psychological institutes became problematic, since the military required a standardized qualification for psychologists in order to deploy them without further training. One major outcome of this alliance between psychology and the military was the 1941 regulation of the diploma examination for psychology, which introduced a uniform curriculum for teaching at psychological institutes. In the midst of the war, German psychology not only gained both official recognition as an academic discipline and partial autonomy from philosophy, but it also took a decisive step towards becoming a distinct profession (). The examination regulations not only incorporated a list of basic subjects, but also a number of practice-oriented subjects such as “Characterology” and “Expression Psychology,” “Applied Psychology,” “Psychological Diagnostics,” and “Biological-medical Auxiliary Sciences” (). The introduction of clinical courses into the diploma examination regulations provoked fierce criticism from leading physicians such as Ernst Rüdin and Max de Crinis, who warned against an intrusion of “quacks and amateurs” into their clinics (). After Rüdin and de Crinis intervened with the Ministry of Education, the clinical courses were withdrawn from the diploma examination regulation just one year after they were introduced. Despite this setback and the fact that most universities were unable, in any case, to implement the new examination regulations before the end of the war due to a lack of resources (), from this time onwards, applied subjects became an integral part of psychologists’ academic training.

Besides the military, another institution was particularly successful in attracting psychologists during the Nazi era: in 1936, the “German Institute for Psychological Research and Psychotherapy” was established under the auspices of physician Matthias Heinrich Göring (; ). Göring’s mission was to unite and synthesize all existing branches of psychotherapy into what he named “German soul therapy” [“Deutsche Seelenheilkunde”]. As repression of Jewish psychoanalysts increased and the German Psychoanalytic Association was disbanded in 1938, the “Göring-Institute” became the leading institution in Nazi Germany offering licensed psychotherapeutic training for physicians as well as nonmedical candidates. There, “laymen” could enter a two year-training for “counselling psychologists,” after which they could legally offer psychotherapeutic services () that were even reimbursed by some insurance companies. While doctors were desperately needed at the front, psychologists were eager to fill the gaps they left behind, quickly growing in numbers at the “Göring-Institute.” In 1937, the Göring Institute started out with 52 members and 15 training candidates. By 1941, the number of “lay” candidates for psychotherapeutic training had doubled, such that physicians were outnumbered among the institute’s members. In 1945, the Göring Institute had 290 members and 215 candidates, the majority of whom were trained as psychologists, not doctors ().

The rise of the dictatorship and the wartime mobilization demanded hard sacrifices from the small German academic community: counted 9 out of 21 professors from the psychological field who lost their positions after the rise of the Nazi regime in 1933. Seven of these left the country, along with more than thirty members of the German Psychological Association. The German Psychoanalytic Association was hit even harder, losing two-thirds of its members after 1933 (). For those who remained, new opportunities opened up. They could demonstrate the usefulness of their expertise in the military, industry, the welfare sector, and the clinical field, where the invention of the “counselling psychologist” gave rise to an entirely new group of psychological practitioners. Despite resistance of the medical profession, the numbers of “lay” therapists grew steadily, paving the way for a new convergence between academic psychology and psychotherapy which was to persist long after the dictatorship ended.

The First Steps Towards Clinical Practice in East and West Germany

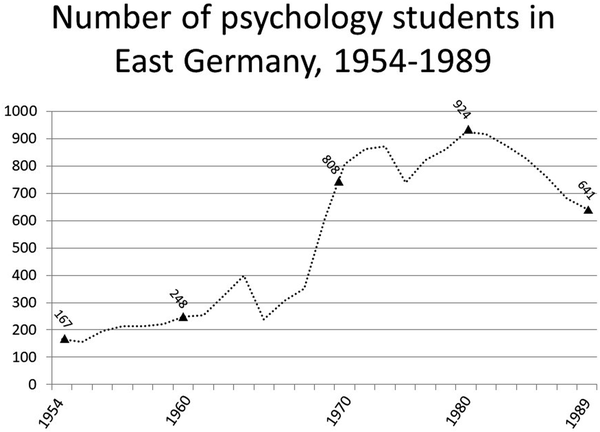

After the downfall of the Nazi regime, the context of psychological work developed in different directions in the East and West: In the East German Soviet Occupation Zone, the reconstruction of academic psychology progressed in small steps. Three institutes reopened after the war in Berlin, Leipzig, and Dresden, while Jena followed in 1960. Student numbers in the GDR were comparatively low, starting at 167 in 1954, rising to slightly more than 800 in the early 1970s, and reaching a peak of 924 in 1980, only to decrease from then on to 641 in 1989 (Figure 1). The practical orientation of GDR psychology quickly became apparent. In 1956, around 60 psychologists were already working in the healthcare sector in East Germany, making up for the chronic shortage of doctors in clinical institutions (). In 1963, the diploma examination regulations for psychology in the GDR were revised (). The new regulations mandated three years of teaching in general subjects and another two years of training in one of four areas of specialization, one of which was clinical psychology. Five years later, the first generation of clinical psychologists who graduated under the new system entered practice. They soon outnumbered physicians in the field of psychotherapy. By 1982, 750 clinical psychologists were employed in different healthcare facilities across the GDR (). Their work was firmly integrated into the institutional framework of psychiatric wards, outpatient clinics, and research-focused institutions under medical supervision. While psychoanalysis was officially banned from psychotherapeutic teaching and practice, group therapy, autogenic training, and talking therapy were particularly popular among psychologists in East Germany (). Even though their numbers remained very small compared to West Germany, psychologists in the GDR enjoyed a considerable level of independence in their therapeutic work and held the legal status of an autonomous profession in the clinical field.

Figure 1

Numbers of psychology students officially enrolled at East German universities according to the Central Administration of Statistics of the GDR. The official statistics did not distinguish between genders. Figures taken from Zentralverwaltung für Statistik, 1954–1990.

Meanwhile, things developed differently in West Germany, where the legal grey zone surrounding psychotherapeutic treatment, a legacy of the Nazi era, remained in place. From 1939, various kinds of health practitioners who were not medically trained were allowed to offer therapeutic treatment under the broad label of “Heilpraktiker,” although their services were usually not reimbursed by public health insurance. Psychologists who worked in clinics, on the other hand, were usually employed to undertake psychological testing, rather than treatment. Psychotherapy was mostly integrated into the medical field of “psychosomatics,” which was dominated by doctors with a Freudian or Neo-Freudian psychoanalytic orientation in the 1950s (). This began to change after 1964, when the Federal Social Court of West Germany ruled that mental disorders had to be treated in the same way as physical illnesses, which meant that citizens in need of psychotherapeutic treatment were entitled to professional support from the health system. Insurance companies began to reimburse costs for psychotherapeutic treatment, but only if it was provided by physicians. However, it soon became obvious that the demand for psychotherapy far exceeded the number of medically trained psychotherapists practicing in West Germany, who numbered only 190 in 1969 (). The West-German psychologist Carl Hoyos noted in 1964 that medical faculties “are unable to provide sufficient numbers of graduates for psychotherapy and other clinical psychological activities. In these circumstances, psychologists were the professional group best suited to fill this gap” (, p. 67). Psychologists were eager to compensate for the lack of medical professionals, and psychotherapeutic institutes profited from training nonmedical candidates. Following a number of lawsuits by patients who were unable to access proper psychotherapeutic treatment, a “delegation procedure” was introduced in 1972, which allowed doctors to transfer patients to nonmedical psychotherapists if physicians were unavailable and treatment was deemed necessary (). However, doctors continued to supervise psychotherapy and decide when it should end. In the absence of any standardized regulations concerning the qualifications of nonmedical psychotherapists, the situation remained unsatisfactory for all groups involved.

Meanwhile, behavioral therapy gained a foothold in West Germany during the 1960s. Its most influential center was founded in 1966 at the Psychological Department of the Max-Planck-Institute for Psychiatry in Munich under the leadership of Johannes Brengelmann, a former assistant of Hans-Jürgen Eysenck in London. In the following years, institutes devoted to research, practice, and training in behavioral therapy opened up all over West Germany, and many of Brengelmann’s students and assistants later became professors in the newly founded clinical departments of psychology institutes in West German universities (). Client-centered therapy and systemic therapy also became increasingly popular in the 1970s, but behavioral therapy consistently dominated the psychological field in West Germany (), even though it was only recognized in 1987 as an official procedure in psychotherapeutic guidelines alongside the established psychodynamic methods of treatment.

In 1973, new diploma examination regulations for psychology were introduced in West Germany, allowing students greater flexibility in their choice of subjects (). One of three “focus areas” in the final examination was applied psychology, the content of which was determined individually by each institute. As student numbers increased, a majority opted for the clinical track wherever it was available, and their teachers soon began to notice that clinical psychology “dominates the career aspirations of students” (, p. 1). In 1971, only 1400 applicants out of 2700 candidates were admitted to a psychology program at a public university in West Germany (). Even though leading representatives of the discipline were generally pleased to see the growing influx of students, they were less sanguine regarding those students’ preferences. Martin Irle, a social psychologist and President of the German Psychological Association from 1976 to 1978, voiced his concerns as follows:

We have been complaining for a decade that our first-year students misunderstand the study of psychology as mere vocational training for a medical profession. [...] I think it’s bad that we give in to the prejudices of our first-year students instead of educating them. I think it’s bad when vacant positions for professors are converted into teaching positions for clinical psychology under the pressure of student demand. […] Psychology is a science, but not a job […]. (, p. 19–20)

Irle feared that the “unrestrained training of almost all students in clinical psychology” (ibid.) risked undermining the integrity of the discipline. If no action was taken, psychology would soon turn “from a science into a profession of medical practitioners” (ibid., p. 22). Although Irle made a strong case for a research-based approach to psychological teaching, the students remained unimpressed. On average over the late 1970s, more than three quarters of psychology students opted for the clinical track during their studies (), and the majority of them later worked in psychotherapy or the psychosocial field. By 1981, more than 40% of the 17,700 psychological practitioners worked as therapists or counsellors in West Germany, which was twice as much as those working as teachers or researchers (, p. 26). While masses of students opted for clinical courses, graduates began to reject psychology’s former role as an “auxiliary science” to medicine and to consider psychotherapeutic treatment as their “own independent task” (, p. 252).

Students’ Expectations and Academic Limitations during the “Psychoboom”

Beyond the legal, economic, and academic spheres, there was also a broader cultural shift that contributed to the expansion of psychotherapy in West Germany. By the end of the 1970s, observers noted the emergence of a “psychoboom” () in society and public media that extended far beyond academic circles. In the preceding years, a broad range of practices ranging from psychoanalysis and group dynamics, to self-help literature, marriage counselling and sexual therapy, and even meditation, Yoga and spiritual practices of various kinds became increasingly popular in the student movement and various leftist and feminist groups. The “therapeutic decade” () of the 1970s saw an unprecedented rise in the popularity of practices concerned with human subjectivity, emotions, interpersonal relations, love, friendship, sex or childhood development, and child-rearing in West Germany and Austria (; ).

In the early days of the student movement, an interest in psychological knowledge and practices was associated with utopian aims such as overcoming authoritarian structures represented by the parental generation, engaging in new “authentic” kinds of relationships, and overcoming the ubiquitous phenomenon of “alienation” in a capitalist society. The leaders of the student movement were primarily interested in classic Freudo-Marxist thinkers such as Marcuse, Adorno, Horkheimer, and Reich. For them, psychology and psychoanalysis should serve political ends by allowing students to criticize and overcome the authoritarian modes of thought and conduct that they were raised with. The more therapeutic practices spread beyond the activist sphere, however, the more they lost their initial political impetus. As the student revolt faded out by the end of the 1970s, a heterogeneous mixture of self-help literature and self-optimization techniques, counselling advice, relaxation methods and spiritual practices made their way into popular literature, magazines, and public media, and also formed the subject of countless courses and seminars. This popularization of “psy-knowledge” and a cultural climate favorable to the “therapeutization” of everyday life fueled the growing influx of students into university psychological institutes (; ; ). However, it seemed almost inevitable that students would be disappointed quickly. In 1970, a survey of students found “considerable differences between their expectations of the tasks and content of psychology studies and the courses offered” (, p. 255). The majority of students became interested in studying psychology through the works of Sigmund Freud, Alfred Adler or Carl Gustav Jung, but these names were hardly ever mentioned in their courses. Another survey among students of psychology from 1993 showed little change in attitudes and predicted further “disappointment, dissatisfaction, a change of study programs or at least a series of reorientations” () among first-year students of psychology. The majority of students sought personal growth, practical guidance and professional expertise on how to improve their understanding of themselves and others, while only one quarter was excited by the prospect of working in an experimental lab. Some teachers considered it almost impossible to inspire students to work at a “scientifically and experimentally oriented psychology institute” (). From their experience, “even the most intensive didactic efforts to make statistical methods courses and experimental labs interesting must fail due to the justified lack of interest of a considerable group of psychology students” (ibid., p. 255–256). A chronic mismatch between students’ expectations and what was taught at university was repeatedly found over the following decades (; ; ; ). During a strike at West German universities in 1988, a group of psychology students questioned their peers about their experiences during their studies and summarized the outcome as follows:

Overall, the conditions for studying found at university do not meet the students’ expectations. The non-transparent structure of the curricula, the lack of practical relevance and the absence of therapy training were cited as particular shortcomings. A typical statement [was]: ‘During the courses I wondered, what has this to do with psychology?’ […] To compensate for the disappointment of their psychology studies, many look for a substitute: either therapy training, internships or work in the social sector. (, p. 70)

It is one of the most interesting paradoxes of German psychology that student numbers continued to grow and few dropped out of their courses, despite the fact that so many students voiced their disappointed with the contents of teaching. One possible explanation could be that, while some students might have developed an interest in psychological research, the majority just hung on until they were finally allowed to enter clinical practice after graduation.

In 1968, the introduction of the “Numerus Clausus” in West Germany allowed universities to introduce admission restrictions and select limited numbers of students per course, based on their school grades. From the introduction of a centralized system for the selection and distribution of student applications in the early 1970s, the number of applicants for psychology programs at public universities constantly exceeded the number of students admitted. In the 1970s, two to three applicants competed for one university place. Over time, the competition continuously intensified, with 15,000 applicants competing for 3.700 spots in 2002 (). Student numbers kept growing all through the 1970s, which increased pressure on psychological institutes to employ sufficient qualified teaching staff. In 1983, the German Science Council observed that

the extension of the previously very limited number of students has turned psychology into a mass subject. […] Psychological institutes and students often do not find the same degree of stimulation, support, communication, competition and promotion of young talent that is necessary for the optimal development of research. (, p. 7)

Furthermore, the council noted that the “sharp increase in demand from students and professional practice” for clinical subjects tested the administrators of psychological departments, despite existing increases in the number of clinical staff over the preceding years (ibid., p. 32).

As a consequence of the “magnetic effect of clinical-psychological practical subjects” (, p. 11), the diploma examination regulations for psychology were again reformed in 1987. The new edition of the curriculum reintroduced a set of compulsory core subjects for all students of psychology, including general psychology, developmental psychology, differential psychology, social psychology, biological psychology, and research methods (). Clinical psychology now represented one of three compulsory “applied areas” along with organizational psychology and pedagogical psychology. Altogether, applied subjects now represented about a quarter of the total curriculum, while the other three quarters were reserved for basic subjects, methodology, and theory and history of science. This relieved psychological institutes of the burden of offering clinical teaching and training, while students who wanted to work as psychotherapists had to complete the major part of their training at their own cost after graduating from university.

After the reunification of Germany, clinical psychologists from East Germany suddenly encountered legal obstacles in their therapeutic work, making it clear that new regulations were needed. The earliest statistical records after reunification counted between 24,500 and 28,000 psychologists across West and East Germany combined, with more than half working in the clinical field (, pp. 9–10). Another survey from the early 1990s of 1630 psychological practitioners in West Germany found that as many as 80% of them worked in the clinical field, offering psychological assessments, counselling, and psychotherapy. Around 70% of them worked in private practice, counselling centers, clinics or psychiatric wards (). While other fields of psychological practice such as occupational psychology were also growing, the clinical field expanded much faster. As psychological practitioners began to outnumber medical practitioners in the welfare system, their fight for legal recognition as clinical experts gained momentum. Several draft laws were discussed and rejected in the 1990s, until the first psychotherapy law was finally passed in 1998 (; ).

The Unprecedented Growth of Psychology Students After the Turn of the Millennium

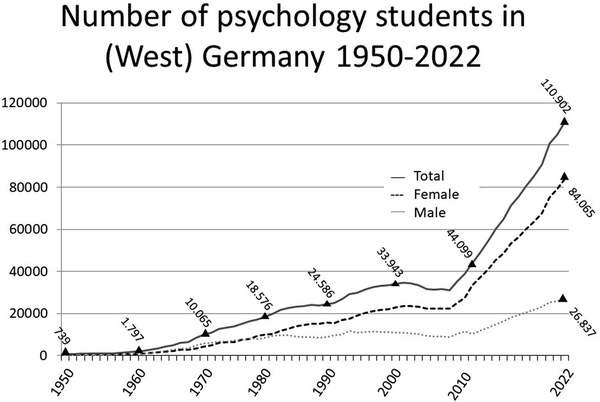

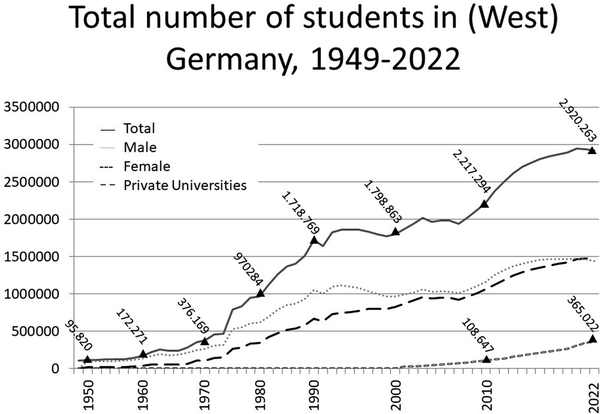

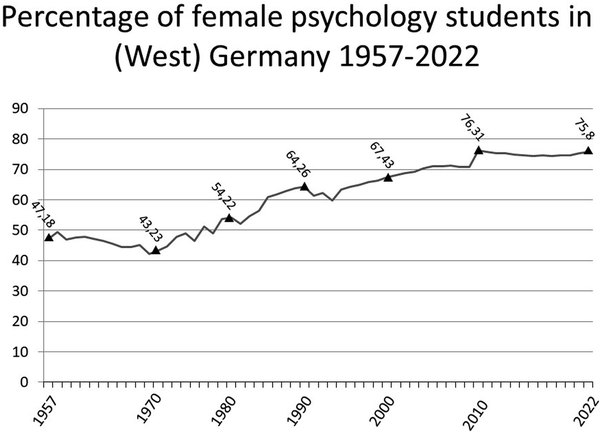

Looking at the long-term development of academic psychology in the second half of the 20th century in West Germany (Figure 2), we find the first major leap during the 1960s, when the number of students increased almost sixfold from 1797 in 1960 to 10,065 in 1970. Growing student numbers were not unique to psychology; the number of students across all disciplines and universities in West Germany increased by a factor of 2.2 over the same period (Figure 3). Thus, while psychology participated in the general trend of growth in higher education, it also exceeded this development significantly. One decisive factor in the exceptional growth in the number of psychology students was the increasing proportion of female students. In the 1950s, almost 50% of psychology students were female (Figure 4), whereas the proportion of female students across all disciplines was only 20% (Figure 3). In 1977, female students exceeded the number of male students of psychology for the first time. Since then, their proportion steadily increased from around 60% in the mid-1980s to 70% at the turn of the millennium. While the overall number of students across all disciplines went through several phases of accelerated growth and stagnation during the second half of the 20th century, the number of psychology students followed a steady upwards trend from 1960 until 2001, with around 10,000 students added each decade (Figure 2). After this long period of continuous growth, it seemed that psychology student numbers had finally peaked at 34,000 in 2002, about two-thirds of whom were female. Over the next five years, numbers even decreased slightly to 31,196 (in 2007). However, major changes in legal regulations and the higher education sector contributed to another, explosive phase of growth after 2007 that overshadowed all that came before.

Figure 2

Numbers of students officially enrolled in psychology at (West) German universities. Students from the GDR are not included because the official statistics of the GDR (1949–1989) did not differentiate by gender. Figures taken from destatis.de/Federal Statistical Office of Germany. Distances between data points on the horizontal axis are partially unequal because some data points are missing from the official reports.

Figure 3

Numbers of students in Germany (not including GDR), including all types of universities, academies (Hochschulen), and private universities. Statistics from the GDR are not included. Figures taken from destatis.de/Federal Statistical Office of Germany. Distances between data points on the horizontal axis are partially unequal because some data points are missing from the official reports.

Figure 4

The percentage of female students of psychology in West Germany since 1957. Figures taken from destatis.de/Federal Statistical Office of Germany. Distances between data points on the horizontal axis are partially unequal because some data points are missing from the official reports.

In 1999, a new law introduced two new groups of health professionals in Germany, the “Psychological Psychotherapist” [“Psychologischer Psychotherapeut”] and psychotherapists for children and teenagers [“Kinder-und Jugendlichenpsychotherapeut”]. Together with medical doctors with psychotherapeutic training, only these groups were allowed to provide licensed psychotherapeutic treatment. A university diploma in psychology was required to enter training as a psychological psychotherapist, while graduates of pedagogy were only admitted to training as child psychotherapists. Training courses (of at least three years duration) in psychoanalysis, depth psychology, or behavioral therapy could be taken at any private institution approved by the authorities. If offered by such licensed professionals, psychotherapeutic treatment could now be fully reimbursed by public health insurance. In short, psychotherapy was finally “recognized as a medical profession, integrated into the public health system and protected from unfair competition” (, p. 211).

The reform also had a significant impact on academic psychology, as university psychological institutes became the main gatekeepers for the psychotherapeutic profession. Leading representatives of clinical departments soon began to voice demands for clinical courses to be made a “core element of all study programs in psychology” (, p. 250). From their perspective, additional professorships in clinical psychology were needed in order to increase the “attractiveness” and “competitiveness” of the discipline and to cover the manifold areas of the growing clinical field, while other subdisciplines were expected to adjust their teaching towards providing the proper theoretical and methodological foundations for later clinical work.

With the number of students admitted to public universities only increasing slowly since the 1990s, this reform would likely not have had such an enormous impact on the growth of academic psychology had it not been for major changes to the European education system over the following decade. The Bologna Declaration, which was endorsed by 29 European countries in 1999, was designed to create a European higher education area that would ensure compatibility and comparability in the education system across the European Union. One key element of this reform replaced the former diplomas with the academic degrees of “Bachelor’s” (after a minimum of 3 years of study) and “Master’s” (another 2 years’ minimum). Ten years after the declaration was signed, most Psychological Institutes in Germany had implemented the reform. That meant that after completing their Bachelor’s, students could apply to any other university across the European Union to undertake a Master’s program. Students’ mobility consequently increased, well beyond Germany’s borders. Notably, students could circumvent the admission restrictions at German universities by earning a Bachelor’s degree in another European country and returning to Germany for their Master’s, or alternatively complete both degrees abroad and then return for psychotherapeutic training. The result was particularly visible in neighboring countries such as Austria, where the number of psychology students from Germany increased from 2% to 47% between 2003 and 2018. By 2018, more than two-thirds of all psychology students in Austrian cities close to the German border came from Germany (). The European unification of higher education generated a continuous stream of students across the German border who, for the most part, tried to find their way back to Germany when they could.

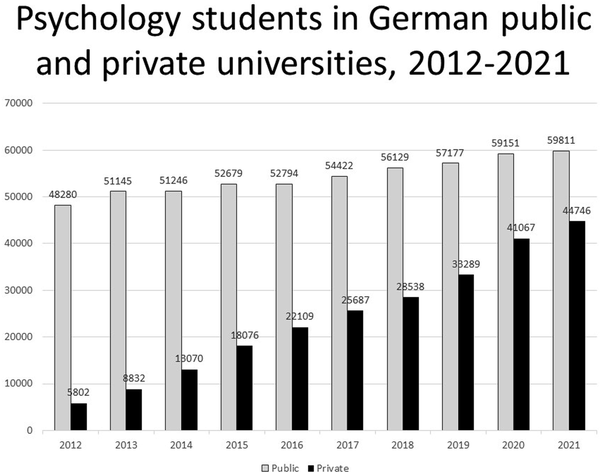

The third major change in the higher education system that contributed to the post-2007 boom of student numbers is the rise of the private education sector. Unlike in North America, the privatization of higher education is a relatively new phenomenon in Germany. Beginning in 2001, the number of students at private universities steadily grew, as did the proportion who studied psychology there. In 2012, only 5802 students of psychology were enrolled at private universities (11.7% of all psychology students), but their numbers grew over the following decade to 44,764 (42% of all psychology students, Figure 5). Since the overall proportion of students at private universities across all disciplines only grew from 5.5% to 11.6% over that period, that means the number of students studying psychology at private institutions was four times the general average. The decade from 2012 to 2021 saw the number of psychology students at private universities increase eightfold, while numbers at public universities increased by only a quarter. If this trend continues, the private sector will soon surpass public universities in numbers of students of psychology. While public universities generally only accept applicants for psychology Master’s programs who have a Bachelor’s in psychology proper, private universities are often more flexible in that regard. In 2014, one such graduate with a Bachelor’s degree in pedagogy and a Master’s degree in psychology from a private university filed a complaint after she was denied access to psychotherapy training by the regional health authorities. After several court cases, the plaintiff was vindicated in 2017 by the Federal Administrative Court. The judgment stated that the 1999 law only listed an academic degree in psychology as an entry requirement for psychotherapeutic training, a criterion which was legally met after completing a Master’s. With the introduction of the two-level system of Bachelor’s and Master’s study programs and the court decision of 2017, an alternative route towards psychotherapy training emerged, a situation which the Association of German Professional Psychologists deplored as risking “harmful wild growth” and dangerous “arbitrariness in access to the profession” (). In other words, the implementation of the Bologna Process and the privatization of higher education led to the unforeseen opening of German Master’s programs and psychotherapy training to graduates from other countries and disciplines who did not have access to the psychotherapeutic field before. As a result, the statistics for 2020 show a new high of 48,000 psychological psychotherapists in Germany ().

Figure 5

Numbers of psychology students in Germany in public (grey) and private universities (black) from 2012 to 2021. Data taken from destatis.de/Federal Statistical Office of Germany.

Thus, a combination of legal, economic and political reforms facilitated an unprecedented surge in the total number of psychology students in Germany from slightly over 31,000 in 2007 to almost 111,000 in 2022. Whilst the discipline benefited immensely from this development in terms of growth, students and trainees pursuing their wish to practice psychotherapy face a long and obstacle-ridden path. Before being allowed to enter practical training, they have to achieve consistent good grades at school and university, or pay large sums to a private university, then pay costly training fees (between 40,000 and 60,000 Euro depending on the chosen psychotherapeutic school). After that, they often have to buy a “practice seat” (“Kassensitz”) from an established colleague in order to work as licensed psychotherapist in private practice. In central urban areas, buying one of these seats could cost several tens of thousands of Euros. In combination with the chronically precarious situation of trainees, this constellation has fostered debates about the need to reform the legal foundations of psychotherapeutic training yet again.

A New Era: The Psychologization of Psychotherapy or the Therapeutization of Psychology?

Looking at the long-term developments in German psychology after the Second World War, we are confronted with the remarkable phenomenon that generations of students fought their way through a study program that often did not match their primary interests. After that, they had to undertake several more years of practical training for which they often paid large fees and received little income, only to spend even more money to enter licensed private practice. What motivated so many thousands of young students to embark on this long and arduous journey?

As hard as it may be to attain, especially for students with any disadvantage in terms of educational and financial support, language or origin, the status of licensed psychotherapist has many advantages. Unlike other areas of psychological practice, psychotherapy is notably protected by law and reimbursed by health insurance in Germany. Once training has been completed, the license as psychotherapist promises a secure income base under the umbrella of the welfare state. Psychotherapeutic practice is also more compatible with family planning than many jobs on the free market (provided the training was completed early enough), since a re-entry after parental leave is usually unproblematic. Working in private practice is usually more flexible than in hospitals or academia, since most psychotherapists are not required to travel abroad or work night shifts. Furthermore, a psychotherapist not only enjoys the image of helping those in need, but also benefits from the social capital connected to an academic degree and holding a state-approved license.

Whatever other reasons might be invoked for students’ choices, it seems clear that German Psychology has long profited from its role as a gatekeeper for future psychotherapists, even though its representatives frequently remarked with dismay that there was an irritating mismatch between their expertise and what their audience expected of them. Wolfgang Schönpflug, professor emeritus of general psychology at the Free University Berlin, reflected on his experiences as academic teacher as follows:

I was torn: Should I feel sorry for the students because they had to put up with me as a lecturer and examiner, or should I feel sorry for myself because I had to teach and examine students who had no interest in my teaching? […] Two worlds collided — the inner world of science in its small world of laboratories and research paradigms, and the outer world with its problems of education, work, health and justice... This could not go well in the long run. […] Thousands of students came to study psychology, and we offered them practical courses in experimental psychology and statistics, as well as many basic subjects. But most of them didn't want that. They wanted psychotherapy. And in order to get training in psychotherapy, they had to get a diploma in psychology first. […] I have tried to promote good science. And how often did I have to hear: No, thank you — we’re more interested in clinical topics. And then I asked: Why are you here? (Ist die Psychologie noch zu retten?, 2019)

The reform of 2020 might have put an end to this dilemma by transferring the major parts of psychotherapeutic training to the university. Basic subjects and research methods remain part of the curriculum, but the representatives of these areas must now compete with clinical psychology more than ever in terms of financial resources, teaching hours, and staff. While many students will learn much more about the topics that initially brought them to university, a considerable proportion of their teachers might feel increasingly under pressure to prove the relevance of their work for clinical practice in the near future.

The consequences of the reform of 2020 are particularly drastic at the Master’s level, which is now divided into programs leading directly to psychotherapeutic training and other areas of specialization. As might be expected, the number of applicants for the clinical track far exceeds the number of places available at public universities. It remains to be seen whether other Master’s programs will be able to attract enough students to keep up with clinical study programs. Otherwise, the pressure may grow even more intense to divert resources so as to admit even more students to the clinical programs.

Representatives of psychoanalysis and depth psychology, which traditionally had a much smaller foothold in German psychological faculties, moreover voiced concerns that the integration of psychotherapy into the university might further weaken the position of schools other than cognitive behavioral therapy in the psychotherapeutic field (). Their fears of a psychologization of psychotherapy are echoed by non-clinical psychologists who see a bleak future as victims of the therapeutization of psychology. This shift could have a deep impact on the power dynamics within the discipline, creating new struggles and potential allies. Whereas traditional debates concerning the unity of psychology focused on the divides between scientific/experimental, humanistic/hermeneutic or theory-/practice-oriented approaches (; ; ), in Germany, these divisions might soon be overshadowed by the competition between clinical and non-clinical subdisciplines. Demographic change may bring the post-millenium growth in student numbers to an end in the foreseeable future, in turn intensifying the competition for students between psychological faculties. Whether non-clinical branches will be able to defend their position at the center of the discipline remains to be seen. What has already become clear, however, is that the latest transformative stage of German psychology has created an imbalance inside the discipline that remains to be resolved.

Conclusion

Over the last decade, German academic psychology has undergone a remarkable transition. Starting out as a small group of male academics engaged in experimental and theoretical research, the field has evolved into a predominantly female, practice-oriented health profession with tens of thousands of students and practitioners. In many ways, the growth of German academic psychology is not unique. It is just one example of the transformation of universities in the Global North after the Second World War, stripping off their former role as institutions devoted to perpetuating a small and highly-educated bourgeois elite, turning into highly bureaucratized institutions disseminating knowledge and training for masses of experts in an industrialized society. However, the statistics presented in this paper show that there is more to the story, in Germany at least, where the growth of academic psychology has continuously outpaced the general increase in student numbers, especially among female students. The factors that led to this were in many ways beyond the control of the discipline, whose representatives repeatedly expressed their concerns about new developments. As for the rise of the clinical areas of psychological practice, one crucial element that facilitated this transformation over many decades was the chronic shortage of medical personnel, which first became urgent during the Second World War, continued in East Germany throughout its existence, and resurfaced in West Germany during the 1970s. The more urgent the lack of therapeutic care became, the more pressure was placed on the medical profession to give up its monopoly on psychotherapy. However, the shortage of medical experts would have made little difference had it not been for the constant pressure from students and practitioners to fill the gap. On the one hand, this situation confronted directors of psychological institutes with the challenge of providing sufficient financial resources, adapting their curricula, and recruiting qualified teachers. On the other hand, the discipline profited immensely from the continuous influx of students, as it went through several growth spurts since the 1960s. As a result, the relationship between academic teachers and the majority of students remained highly ambivalent. Both parties were dependent on the other, despite their different interests and motivations. The repeated revisions to the diploma examination regulations from the 1970s and the two reforms of the law concerning psychotherapeutic training of 1999 and 2020 can be interpreted as successive attempts to solve this issue. But the tensions that arise from the most recent reform have the potential to tear the discipline apart, as one possible outcome of this development could be that psychotherapy and academic psychology again part ways (as suggested by ). A divorce would free non-clinical staff from the pressure to prove their relevance to the clinical field, but it would also risk a massive loss of students, academic posts, and infrastructure. The alternative for non-clinicians, as it seems, is to continue the unhappy marriage while facing the prospect of turning into an auxiliary science for clinical practice.

As of today, clinical psychology has not yet completely ousted all other subdisciplines in Germany. For the foreseeable future, basic psychology subjects and research methods will remain an integral part of academic teaching for all psychotherapists. They will not disappear from curricula, but their representatives face the prospect of becoming a minority within the discipline in the long run. In 2023, clinical psychology held the most professorships (168) in the German Psychological Association (20% of all professors), and also the highest numbers of doctoral students (524, 21% of the total) among all psychological subdisciplines. In the German Psychological Society, which counted more than 5000 members in 2024, the Clinical Section topped all others with over 1000 members. For all others, the pressure to demonstrate the relevance of their work to the clinical field is likely to increase, and candidates for academic positions who hold a license to practice psychotherapy can expect a better chance of employment than their colleagues without clinical training. A hierarchy is likely to emerge between clinical and non-clinical psychologists, with the former occupying the large areas of psychological practice defined by law, while the latter remain excluded from it.

The profound transformation of German psychology provides a remarkable example of the variety of sociological, economic and cultural factors that foster, obstruct and direct the development of academic disciplines and professions. While these contextual factors are common points of reference in the historiography of science, students’ preferences and interests are only rarely taken into account in the scholarship. Their ability and power to change the scope and contents of teaching might appear very limited at any particular moment, but grows impressive when we take a long-term, intergenerational perspective. For historians of psychology, this case study opens up a new dimension through which to examine the relationship between the development of scientific knowledge and underlying social dynamics. For teachers of psychology today, the German case illustrates that without reflecting on the social context of their work, they risk being marginalized at some point. And finally, for students, it shows that as they enter and progress in their academic careers, by simply voting with their feet, they contribute to shaping the future development of their discipline.

Action Editors Wade E. Pickren and Thomas Teo.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Note

1. If not indicated otherwise, all citations from German are translated by the author.

References

- Ash M. (1984). Disziplinentwicklung und Wissenschaftstransfer. Deutschsprachige Psychologen in der Emigration. Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, 7(4), 207–226. https://doi.org/10.1002/bewi.19840070402

- Ash M. (1985). Gestalt psychology in German culture, 1890-1967. In Holism and the quest for objectivity. Cambridge University Press.

- Augenstein J., Beller J., Vogel S. (1986). Wissenschaftsverständnis und Studienzufriedenheit von Psychologiestudierenden. Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie und Gruppendynamik, 11(3), 17–23.

- Bach G., Molter H. (1979). Psychoboom. Wege und Abwege moderner Psychotherapie. Reinbek bei Hamburg.

- Benecke C. (2019). Die Zukunft der Psychotherapieverfahren im neuen Psychotherapiestudium. Psychotherapeutenjournal, 4, 393–401.

- Bewerber-Rekord bei Medizin und Psychologie. (2002). Der spiegel. Online available at. https://www.spiegel.de/lebenundlernen/uni/zvs-bewerber-rekord-bei-medizin-und-psychologie-a-212582.html

- Bühner M. (2023). Zur Lage der Psychologie. Psychologische Rundschau, 74(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042/a000616

- Buss A. (Ed.), (1979). Psychology in social context. Irvington.

- Cocks G. (1997). Psychotherapy in the third reich: The göring institute (2nd ed.). Transaction Publ.

- Danziger K. (1990). Constructing the subject. Historical origins of psychological research. Cambridge University Press.

- Dorsch F. (1963). Geschichte und Probleme der angewandten Psychologie. Hans Huber.

- Eitler P., Elberfeld J. (Eds.), (2015). Zeitgeschichte des Selbst. Therapeutisierung, Politisierung, Emotionalisierung. Biefeld. transcript.

- Fisch R., Orlik P., Saterdag H. (1970). Warum studiert man Psychologie? Psychologische Rundschau, 21(4), 239–256.

- Gerichtsurteil. (2017). Pressemitteilung des BDP zur Entscheidung des Bundesveraltungsgerichts über Zulassungsvoraussetzung für Psychotherapeutenausbildung. Online available at. https://www.bdp-abp.de/418

- Geuter U. (1992). The professionalization of psychology in Nazi Germany (Holmes, R. J., Trans). Cambridge University Press.

- Geyer M. (Ed.), (2011). Psychotherapie in Ostdeutschland. Geschichte und Geschichten 1945-1995. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

- Green C. (2015). Why psychology isn’t unified, and probably never will be. Review of General Psychology, 19(3), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000051

- Gundlach H. (1996). Faktor Mensch im Krieg. Der Eintritt der Psychologie und Psychotechnik in den Krieg. Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte, 19(2-3), 131–143. https://doi.org/10.1002/bewi.19960190211

- Handerer J. (2014). Zwischen Natur- und Geisteswissenschaft. Zum Fachverständnis und zur Studienzufriedenheit von Psychologiestudierenden. In Krämer M., Weger U., Zupanic M. (Eds.), Psychologiedidaktik und Evaluation X (pp. 3–9). Shaker Verlag.

- Heidelberger Arbeitsgruppe zur Erneuerung der Psychologie. (1994). Das Psychologiestudium der Zukunft oder: Was wir noch immer zu träumen wagen. Journal für Psychologie, 2(1), 71–79.

- Herrmann T. (1972). Zur Lage der Psychologe: 1972. Psychologische Rundschau, 24, 19–37.

- Hofmann H., Stiksrud A. (1993). Wege und Umwege zum Studium der Psychologie III. Psychologische Rundschau, 44(4), 250–256.

- Hörmann G., Nestmann F. (1985). Die Professionalisierung der Klinischen Psychologie und die Entwicklung neuer Berufsfelder in Beratung, Sozialarbeit und Therapie. In Ash M., Geuter U. (eds.), Geschichte der deutschen Psychologie im 20. (pp. 252–2859). Westdeutscher Verlag.

- Hoyos C. G. (1964). Denkschrift zur Lage der Psychologie. Franz Steiner.

- Irle M. (1979). Zur Lage der Psychologie. In Eckensberger L. (Ed.), Bericht über den 31 Kongreß der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Psychologie in Mannheim 1978 (Vol 1, pp. 3–23). Hogrefe.

- Irle M., Strack F. (1979). Psychologie in deutschland. In Ein Bericht zur Lage von Forschung und Lehre. Verlag Chemie.

- Jaeger S., Staeuble I. (1981). Die Psychotechnik und ihre gesellschaftlichen Entwicklungsbedingungen. In Stoll F. (Ed.), Kindlers »Psychologie des 20. Jahrhunderts«. Arbeit und Beruf (Vol 1, pp. 49–91). Beltz.

- Jansz J., van Drunen P. (Eds.), (2004). A social history of psychology. Blackwell.

- Kimble G. (1984). Psychology’s two cultures. American Psychologist, 39(8), 833–839. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.39.8.833

- Kintzel R. (1992). Das Studium der Psychologie - eine Anleitung zum Unglücklichsein? Erfahrungen aus einem teilautonomem Studienprojekt. Journal für Psychologie, 1(1), 69–70.

- Kovacs C., Batinic B. (2020). Psychologie in Österreich. Studiums- und Berufsstatistiken. Psychologische Rundschau, 71(4), 343–352. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042/a000505

- Krampen G. (1992). Zur Geschichte des Psychologiestudiums in Deutschland. Report Psychologie, 17(1), 18–26.

- Krampen G., Greve W. (1993). Psychologie studieren heute: Zur Rahmenordnung für das Psychologiestudium in Deutschland aus dem Jahr 1987. Report Psychologie, 18(7), 9–13.

- Leuzinger-Bohleber M., Leiendecker C. (2019). Pluralität oder Uniformität? Plädoyer für ein differenziertes Angebot unterschiedlicher Psychotherapieverfahren für Praxis, Ausbildung und Forschung. Projekt Psychotherapie, 2, 23–26.

- Lück H. (2020). Die Diplomprüfungsordnung für Studierende der Psychologie – eine nationalsozialistische Prüfungsordnung? In Wieser M. (Ed.), Psychologie im Nationalsozialismus (pp. 47–72). Peter Lang.

- Malich L. (2020). The history of psychological psychotherapy in Germany: The rise of psychology in mental health care and the emergence of clinical psychology during the 20th century. In Pickren W. E. (Ed.), Oxford encyclopedia of the history of psychology (epub). Oxford University Press.

- Malich L. (2021). Die Verhaltenstherapie als genuin psychologisch? Zum Verhältnis zwischen Psychologie und Medizin am Max-Planck-Institut für Psychiatrie in den 1960er und 1970er Jahren. Psychologische Rundschau, 72(3), 192–200. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042/a000545

- Moede W. (1926). Kraftfahrer- eignungsprüfungen beim deutschen heer 1915-1918. Industrielle Psychotechnik, 3(1), 23–28.

- Ottersbach G., Grabska K., Schwarze E. (1990). Psychologie: Das verfehlte Studium? Wie Psychologiestudenten ihr Studium sehen, beurteilen und bewältigen. Leuchtturm.

- Patzel-Mattern K. (2010). Ökonomische Effizienz und gesellschaftlicher Ausgleich. Franz Steiner.

- Pechmann B. (2021). Psychotherapieausbildung: Für eine vielfältige Qualifizierung. Deutsches Ärzteblatt, 2, 63.

- Pickren W., Rutherford A. (2010). A history of modern psychology in context. John Wiley & Sons.

- Probst P. (1993). Die deutsche Psychologie nach der Wiedervereinigung. Report Psychologie, 18(3), 8–15.

- Rahmenordnung. (1973). Rahmenordnung für die Diplomprüfung in der Psychologie. Psychologische Rundschau, 24(3), 219–226.

- Regine L. (1985). Erinnern und Durcharbeiten. Zur Geschichte der Psychoanalyse und Psychotherapie im Nationalsozialismus. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.

- Rief W. (2020). Die Zukunft der Psychotherapie nach der Ausbildungsreform. Verhaltenstherapie, 30(2), 101–103. https://doi.org/10.1159/000507944

- Rief W., Hautzinger M., Rist F., Rockstroh B., Wittchen H.-U. (2007). Klinische Psychologie und Psychotherapie: Eine Standortbestimmung in der Psychologie. Psychologische Rundschau, 58(4), 249–259. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042.58.4.249

- Rösler H.-D. (2011). Zur Geschichte der Klinischen Psychologie in der DDR. Report Psychologie, 6(2), 11–12.

- Ruck N., Luckgei V., Rothmüller B., Franke N., Rack E. (2022). Psychologization in and through the women's movement: A transnational history of the psychologization of consciousness-raising in the German-speaking countries and the United States. Journal of the History of the Behavioral Sciences, 58(3), 269–290. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbs.22187

- Rzesnitzek L. (2020). „Vorkämpferin fürs Kollektiv” oder „Zersetzerin der Seele”? Zur klinischen Psychologie in der DDR. In Kumbier E. (Ed.), Psychiatrie in der DDR II. Weitere Beträge zur Geschichte (pp. 161–182). be.bra.

- Schildt H. (2007). Vom „nichtärztlichen” zum Psychologischen Psychotherapeuten/KJP. Psychotherapeutenjournal, 2, 118–128.

- Schönpflug W. (2017). Professional psychology in Germany, national socialism, and the second world war. History of Psychology, 20(4), 387–407. https://doi.org/10.1037/hop0000065

- Schönpflug W. (2019). Ist das Ende der Psychologie gekommen? Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. Retrieved from. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/karriere-hochschule/neues-gesetz-ist-das-ende-der-psychologie-gekommen-16099105.html

- Schönpflug W. (2021). Der Weg zur Reform der Psychotherapeuten- und Psychotherapeutinnenausbildung. Psychologische Rundschau, 72(3), 211–219.

- Schönpflug W. (2022). Kurze Geschichte der Psychologie und Psychotherapie (1783-2020). Peter Lang.

- Schorr A. (1995). German psychology after reunification. In Schorr A., Saari S. (Eds.), Psychology in Europe. Facts, figures, realities (pp. 35–58). Hogrefe.

- Schröter M. (2009). »Hier läuft alles zur Zufriedenheit, abgesehen von den Verlusten …« Die Deutsche Psychoanalytische Gesellschaft 1933–1936. Psyche – Zeitschrift für Psychoanalyse, 63(11), 1085–1130.

- Schulte D. (2021). Der lange weg zum psychotherapeutengesetz. Vier stationen in drei jahrzehnten. Psychologische Rundschau, 72(3), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042/a000546

- Spinath B. (2021). Zur Lage der Psychologie. Psychologische Rundschau, 72(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042/a000521

- Spitzer C., Strauß B. (2022). Doing Gender (und Diversity) in der Psychotherapie. Psychotherapie, 67(4), 281–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00278-022-00608-8

- Tändler M. (2016). Das therapeutische Jahrzehnt. Der Psychoboom in den siebziger Jahren. Wallstein.

- Tändler M., Jensen U. (eds.). (2012). Das Selbst zwischen Anpassung und Befreiuung. Psychowissen und Politik im 20. Wallstein.

- Tuschen-Caffier B., Antoni C., Elsner B., Bermeitinger C., Bühner M., Erdfelder E., Fydrich T., Gärtner A., Gollwitzer M., König C. J., Spinath B. (2020). Quo vadis „Studium und Lehre” in der Psychologie? Denkanstöße für die Neukonzeption von Studiengängen. Psychologische Rundschau, 71(4), 384–393. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042/a000513.

- Valentine E. (2006). Beatrice Edgell. Pioneer Woman Psychologist. Nova Science.

- Vangermain D., Brauchle G. (2010). Ein langer Weg der Professionalisierung: Die Geschichte des deutschen Psychotherapeutengesetzes. Verhaltenstherapie, 20(2), 93–100.

- Wieser M. (2020). The concept of crisis in the history of Western Psychology. In Pickren W. (Ed.) Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Psychology: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190236557.013.470

- Wieser M. (2021). „Deutsche Seelenheilkunde” und die Erfindung des „behandelnden Psychologen“. Zum Verhältnis von Psychologie und Psychotherapie im Nationalsozialismus. Psychologische Rundschau, 72(3), 181–191. https://doi.org/10.1026/0033-3042/a000544

- Wissenschaftsrat. (1983). Empfehlungen zur Forschung in der Psychologie. Wissenschaftsrat.

- Wolfradt U., Billmann-Mahecha E., Stock A. (Eds.), (2015). Deutschsprachige Psychologinnen und Psychologen 1933–1945. Ein Personenlexikon, ergänzt um einen Text von Erich Stern. Springer.

- Woodward W., Ash M. (Eds.), (1982). The problematic science. In Psychology in nineteenth-century thought. Praeger.

- Wundt W. (1909). Über reine und angewandte Psychologie. Psychologische Studien, 5, 1–47.